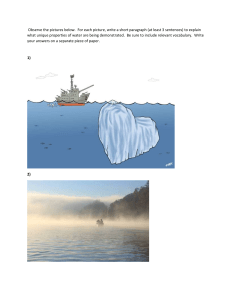

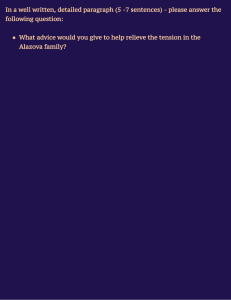

1 1. 2. 3. 4. 1. 2. 3. 1. Developing an Outline Whether they are called mind maps, concept maps, or just oldfashioned outlines, such tools help the writer organize his/her material logically by helping him/her sort and classify the material systematically. A secondary outcome of the process of sorting and classification is the ability to see the relationships that exist between ideas in our writing. This insight helps the writer develop an organized plan for presenting the material. Outlines, in all their forms, serve four basic functions: to present a logical, general description, to summarize schematically, to reveal an organizational pattern, and to provide a visual and conceptual design of the writing. An outline reflects logical thinking and correct classification. Beginning an Outline Before we begin to write an outline, we must have progressed far enough into our planning such that we know the at least three things: the purpose of our paper, the thesis of our paper, and our audience. Then, we can brainstorm and list all the ideas you want to include in this writing, organize our work by grouping ideas together that are related to each other, order our work by dividing the material into groups ranging from the general to the specific, or from abstract to concrete, and label the work by creating main and subtopic headings and writing coordinate levels in parallel form. An outline has a balanced structure which uses the principles of parallelism, 2. coordination, 3. subordination, and 4. division. 1. Parallelism Whenever possible, in writing an outline, coordinate heads should be expressed in parallel form. That is, nouns should be made parallel with nouns, verb forms with verb forms, adjectives with adjectives, and so on. (Example: Nouns - computers, programs, users; Verbs - to compute, to program, to use; Adjectives - home computers, new programs, experienced users.) Although parallel structure is desired, logical and clear writing should not be sacrificed simply to maintain parallelism (For example, there are times when nouns and gerunds used at the same level of an outline are acceptable.) Reasonableness and flexibility of form is preferred to rigidity. 2. Coordination In outlining, those items which are of equal significance have comparable numeral or letter designations; an A is equal a B, a 1 to a 2, an a to a b, etc. Coordinates should be seen as "having the same importance." Coordination is a principle that enables the writer to maintain a coherent and consistent document. Correct coordination A. Word processing programs B. Database programs C. Spreadsheet programs Incorrect coordination A. Word processing programs B. Word C. Excel Word is a type of word-processing program and should be treated as a subdivision. Excel is a type of 2 A. 1. 2. B. 1. 2. 3. A. 1. 2. B. 1. 2. A. 1. 2. 3. spreadsheet program. One way to correct coordination would be: Types of programs Word Excel Evaluation of programs Word Excel ... such tools help the writer organize his/her material logically by helping him/her sort and classify the material systematically ... Subordination To indicate relevance, that is levels of significance, an outline uses major and minor headings. Thus, in ordering ideas you should organize material from general to specific or from abstract to concrete - the more general or abstract the concept, the higher the level or rank in the outline. This principle allows your material to be ordered in terms of logic and requires a clear articulation of the relationship between component parts used in the outline. Subdivisions of a major division should always have the same relationship to the whole. Correct subordination Word processing programs Word WordPerfect Presentation programs MS PowerPoint Corel Presentations Faulty subordination Word processing programs WordPerfect Useful Obsolete There is an A without a B. Also, 1, 2, and 3 are not equal; WordPerfect is a type of word processing program, and useful and obsolete are qualities. One A. 1. 2. 3. B. A. 1. 2. a. b. B. 1. 2. way to correct this faulty subordination is: A. WordPerfect 1. Positive features 2. Negative features B. Word 1. Positive features 2. Negative features 4. Division To divide you always need at least two parts; therefore, there can never be an A without a B, a 1 without a 2, an a without a b, etc. Usually, there is more than one way to divide parts; however, when dividing use only one basis of division at each rank and make the basis of division as sharp as possible. Example 1 Microcomputer hardware Types Cost Maintenance Microcomputer software Example 2 Computers Mainframe Micro Floppy Disk Hard disk Computer Uses Professional Personal 5. Form The most important principle for an outline's form is consistency. An outline can use TOPIC or SENTENCE structure, but be consistent in form all the way through. A TOPIC outline uses words or phrases for all points; uses no punctuation after entries. Advantages — presents a brief overview of work; is generally easier 3 and faster to write than a sentence outline A SENTENCE outline uses complete sentences for all entries; uses correct punctuation Advantages — presents a more detailed overview of work including possible topic sentences; is easier and faster for writing the final paper. An outline can use either alphanumeric (usually with Roman numerals) form or a decimal form. Alternating patterns of upper and lower case letters with alternating progressions of Roman and Arabic numerals mark the level of subordination within the alphanumeric form of the outline. Progressive patterns of decimals mark the levels of subordination in decimal form of outlining. The decimal form has become the standard form in scientific and technical writing. For example, The alpha-numeric form I. A. B. 1. 2. a. b. The decimal form 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.2.1 1.2.2 1.2.2.1 1.2.2.2 Parts of a Paragraph A paragraph is a group of sentences about one topic. It contains a topic sentence, supporting details and sometimes a concluding sentence. The sentences follow one another from the beginning to the end of the paragraph. A paragraph is usually part of a longer piece of writing, such as a letter or essay. The topic sentence The topic sentence is usually the first sentence of the paragraph. It states the main idea of the paragraph. A good topic sentence tells the reader exactly what the rest of the paragraph will be about. The supporting sentences The supporting sentences are the middle sentences of the paragraph. They provide details such as explanations or examples that expand on or support the topic sentence. Supporting sentences are sometimes connected by transition words or phrases. The concluding sentence A concluding sentence is sometimes used in longer paragraphs to sum up the ideas presented. It expresses the same idea as the topic sentence but in different words. It can start with a transition such as clearly or in conclusion. Seven Types of Paragraph Development 1. Narration Comments on narration: 4 • Normally chronological (though sometimes uses flashbacks) • A sequential presentation of the events that add up to a story. • A narrative differs from a mere listing of events. Narration usually contains characters, a setting, a conflict, and a resolution. Time and place and person are normally established. In this paragraph, the "story" components are: a protagonist (Hanson), a setting (the park), a goal (to camp), an obstacle (nature), a climax (his panic), and a resolution (leaving). • Specific details always help a story, but so does interpretive language. You don't just lay the words on the page; you point them in the direction of a story. • This narrative serves as the opening anecdote that illustrates the topic of the story 2. Exposition Comments on exposition: • Exposition is explanatory writing • Exposition can be an incidental part of a description or a narration, or it can be the heart of an article • Aside from clarity, the key problem with exposition is credibility. What makes your explanation believable? Normally, writers solve this problem by citing authorities who have good credentials and good reason to be experts in the subject. • This paragraph also happens to serve as the justifier or "nut graf" for the little article: the paragraph that, after an indirect opening, specifies the topic of the article, why it is important, and what is to come. 3. Definition Comments on definition: • Never define anything by the "according to Webster's" method. Meaning is found in the world, not in the dictionary. Bring the world into your story and use it to define your terms. • Saying what something is NOT can help readers; but make a strong effort to say what it IS. 4. Description Comments on description: • Description is not what you saw, but what readers need to see in order to imagine the scene, person, object, etc . • Description requires you to record a series of detailed observations. Be especially careful to make real observations. The success of a description lies in the difference between what a reader can imagine and what you actually saw and recorded; from that gap arises a spark of engagement. • Use sensory language. Go light on adjectives and adverbs. Look for ways to describe action. Pay special attention to the sound and rhythm of words; use these when you can. Think that your language is not so much describing a thing as describing a frame around the thing--a frame so vivid that your reader can pour his or her imagination into it and "see" the thing--even though you never showed it. Portray. Also evoke. • The key problem in description is to avoid being static or flat. Adopt a strategy that makes your description into a little story: move from far to near, left to right, old to new, or, as in this example, down a river, to give your description a natural flow.Think of description as a little narrative in which the visual characteristics unfold in a natural, interesting, dramatic 5 order. Think of what pieces readers need, in what order, to construct a scene. Try making the description a little dramatic revelation, like watching an actor put on a costume--where you cannot decipher what the costume means until many of the parts are in place. • Never tease readers or withhold descriptive detail, unless for some strange reason that is the nature of your writing. Lay it out. Give your description away as generously as the world gives away sights. Let it show as transparently as seeing. • The cognitive difficulty in description is simple: People see all-at-once. But they read sequentially, one-part-atthe-time, in a series of pieces. Choose the pieces. Sequence them so they add up. Think: Readers first read this, now this, now this; what do they need next? • Remember, you never just describe something: The description is always part of a larger point. Use the description to make your point, or to move your story along. 5. Comparison Comments on comparison: • There is a helpful technique for writing a comparison. If you follow it, your comparisons will benefit. • Before writing a comparison, draw up a chart and fill it in, to make certain you have all the elements necessary to write a comparison. As in the model below, list the two items being compared, and the criteria by which they will be compared. If you do not make such a chart, there is a chance you will have a hole in your comparison . o Criteria O'Leno Lloyd Beach o noise quiet noisy o people solitude available busy crowds o water resources river to swim and canoe Atlantic beach o natural features forest beach o wildlife abundant, forest type fish and seabirds • Then choose whether to to "down the columns" or "across the rows" in writing your description. Either describe all of O'Leno and compare it to all of Lloyd Beach by working "down" columns two and three, or take the first category, "noise" and compare the two parks in terms of it, then the next category, and so on "across the rows. " • Once you commit to a "down" or "across" strategy, stick with it till the end of the comparison. 6. Process Analysis Comments on process analysis: • In describing how a process happens or how to perform a series of actions, always think of your readers: can they follow this? • Analyze the process into a series of steps. Put the steps into sequence . • Then isolate the steps: number then, use bullets, put them in separate paragraphs • Use illustrations keyed to the steps when appropriate: people can often read diagrams better than they can read lists of steps • Always ask an outsider to read your process analysis to see if it can be followed. Once you are close to a subject, it is difficult to know when you have left something out. 7. Persuasion Comments on persuasion: • This paragraph is but a small example of the kind of writing used widely in editorials and columns, and 6 it uses a direct, exhortatory approach: Believe Me and Do It! • This persuasive paragraph also serves as the ending to this little article and brings a sense of closure in the form of, OK, now get up and act!" • To persuade people to change their minds or take an action, more is needed than your opinion or sense of conviction. You need to supply them with the information, analysis, and context they need to form their own opinions, make their own judgments, and take action. • Remember: Readers are interested in only one opinion--their own. If you can help them formulate and deepen that opinion, they will be glad they read your article. Paragraph Development A paragraph is a group of related sentences that are centered on a main idea. The purpose of a paragraph varies according to the type of writing, but generally, a paragraph is used to develop an idea or give evidence in support of the essay’s central thesis or argument. Paragraphs generally consist of three parts: topic sentence, supporting sentences, and concluding sentences. Topic Sentence: Topic + Controlling Idea Generally, the topic sentence is the first (or second) sentence of your paragraph, and it contains the main idea of the paragraph. The topic sentence should be specific and tell the reader exactly what the paragraph will be about. A well-structured topic sentence is made up of a topic and a controlling idea. Supporting Sentences Each supporting sentence should contribute to the main idea. Supporting sentences help explain or prove the topic sentence, and they may include quotations or paraphrasing of source information with proper citations. Concluding Sentences Concluding sentences close the paragraph and often remind the reader of the main point. Note: this is not simply a restatement of the topic sentence. In the above example, the final sentence functions as a concluding sentence because it restates the main idea in a different way and signals the end of the paragraph. Constructing Effective Paragraphs: Unity and Coherence Unity: Each paragraph should contain one, and only one, main idea. Including unrelated ideas within one paragraph leaves little room for adequate discussion or explanation and may cause your ideas to seem jumbled or unclear, thus confusing your reader. If there is more than one idea in a paragraph, separate the ideas into different paragraphs and try to elaborate on each. Coherence: Each sentence in a paragraph should fit logically within that paragraph and writers should use 7 transitions to help link the ideas and guide the reader through the text easily. In other words, one sentence should lead logically to the next. This is most easily accomplished through the use of transition words (see Common Transitions table below). THE WRITING PROCESS 1. PREWRITING: We should get one thing straight right away: If you sit around waiting for inspiration before you write, you may never get anything written. You see, inspiration does not occur often enough for writers to depend on it. In fact, inspiration occurs so rarely that writers must develop other means for getting their ideas. Collectively, the procedures for coming up with ideas in the absence of inspiration are called prewriting. The term prewriting is used because these procedures come before writing the first draft. Some others may also call these procedures invention. The following are different prewriting options: 1. FREEWRITING: Allows you to generate thoughts that will help you formulate ideas to write about. Put your pen to the paper, and begin to write. Do not stop to think, organize, critique, etc. – Just Write! Write as fast as you can, the faster the better. 2. CLUSTERING: This is a good visual aid that shows the connection between thoughts and allows patterns to be seen. In the center of your page, write the main idea or stimulus word that you are considering and put a circle around it. 3. LISTING: This is like a shopping list of phrases. On your paper, write down any thought or feeling that comes to mind about a particular topic. This is similar to freewriting in that you should not censor yourself – Just write! This process will help you get all of those mixed up thoughts in your head on paper, so you can sift through them afterwards. Here’s an example of a list on the topic “How I felt when I failed my midterm:” was disappointed, felt defeated, also inspired to do better next time, embarrassed to tell anybody wanted to blame the teacher, got teased by my brother, the A student, afraid I wouldn’t pass the class, went to The Writing Center for extra help Once you are done, go through the list, choose the ideas that work for you, and cross off the ideas that do not. You may also continue to write ideas down as you go through this process. When you feel you are done, you can go ahead and number the ideas that are left in the order you think they should appear in your draft. 8 This will give you an informal outline that will help in the next step of the writing process, drafting. 4. BRAINSTORMING: Ask yourself questions about your topic. Who, what, when, where, why and how are good questions to start with. Whose fault is the F? What happened exactly? When did I stop studying?/Why did I stop studying? Where can I go from here? Why do I think the teacher gave me an F? How can I improve my grade? These questions will be helpful in your drafting stage if you are stuck trying to find more to write about. If you are trying to expand your essay but you are unable to come up with another important topic to discuss, consider asking yourself questions like these to generate more ideas. DRAFTING: Once writers feel they have generated enough ideas during prewriting to serve as a departure point, they make their first attempt at getting those ideas down. This part of the writing process is drafting. Typically, the first draft is very rough, which is why it so often is called the rough draft. The rough draft provides raw material that can be shaped and refined in the next stages of the writing process. Perhaps you know what you want to say but you do not know how to say it in your draft. Here are a few tips to get you started: Think about your audience. Who are you telling this information to? Speak your thoughts into a tape recorder. Sometimes, we don’t write what we want to say. Therefore, speaking into a tape recorder, saying what you want to say and then transcribing your thoughts will help you with word structure. Set small goals for yourself. At the beginning of your project, plan to only prewrite. The next time you sit down to work on it, plan on writing an informal outline. Next, plan to write a draft of your introduction and on and on. Breaking the project down into smaller steps makes it less overwhelming. Sometimes, we get writer’s block because we think we have to write the introduction and thesis statement before we can move on. Remember, you can change the introduction and thesis as you get further along in your paper. If you are really stuck, you can write the introduction and thesis last. They might be easier to write once you have the rest of the draft. This is only a first draft; you don’t need to censor your thoughts. Later on, you will be able to fix whatever needs fixing. REVISING: Revising calls on the writer to take the raw material of the draft and rework it to get it in shape for the reader. This reworking is a time-consuming, difficult part of the process. It requires the writer to refine the content so that it is clear, so that points are adequately supported, and so that ideas are expressed in the best way possible and in the best order possible. This step is focused on the content of your draft; spelling, grammar and punctuation will come in the final stage of the writing process. Once you have completed your first draft, the first step in revising is to walk away and let the paper sit. We often miss our own mistakes because we think we see something that is not there. Walking away and coming back 9 later allows you to read your paper with a fresh perspective. Read your draft out loud to yourself. Our ears can catch problem areas that our eyes cannot. After fully examining your draft, identify at least two corrections that will make your draft better. Write a second draft without looking at your first draft. This is an effective way of revising because usually you remember the best parts, forget the worst parts, and add new ideas. EDITING: Experienced readers will expect your writing to be free of errors. Therefore, you have a responsibility to find and eliminate mistakes so that they do not distract or annoy your reader. Many writers make the mistake of hunting for errors too soon, before they have revised for the larger concerns of content and effective expression. Editing should really be saved for the end of the process. The computer is an excellent tool for the editing stage. If you have already typed your essay on the computer, then you will see that certain words, phrases and sentences are underlined either in red or green. Red indicates a spelling or lexical (the meaning of a word) error. Green indicates a grammatical, punctuation or sentence structure error. Like the revising stage, reading your paper aloud will help you catch structural errors that may otherwise be missed. Edit more than once! After you have completely edited your paper, walk away and return some time later to reedit. Sometimes, we make careless errors because we think we wrote it correctly and have actually made an obvious mistake. Use an Editing Checklist: Have you read your work aloud to listen for problems? Did you check every possible misspelling in a dictionary or with a computer spell checker? Make sure every comma is being used correctly (comma splices and runons). Do you have any sentence fragments? Are you using verbs correctly? Did you check your use of pronouns? Did you check your use of modifiers? Are you confident your punctuation is used correctly? Are your capital letters correct?