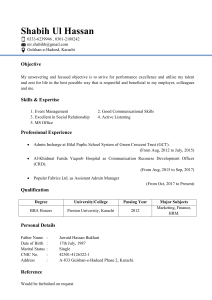

Karachi: A Colonial Perspective of the Port City in the Age of Industrialization Introduction: The pencil drawing depicted in photograph 1 captures the sight which greeted travelers as they approached the city of Karachi in the early nineteenth century. Drawn in 1832 by a British merchant John Boyd, and part of an archived collection in the British Library; the photo is a rare insight into the state of the Karachi harbor before the British Empire began work on its improvement, giving us a peak into the city’s early history. Before it functioned as a major British port city, Karachi existed as a small village consisting of three fishing islands: Manora, Bhit, and Baba. This essay will explore Karachi’s story in the late eighteenth and the nineteenth century: unravelling its evolution from a fishing village to a major port city in the age of industrialization. The primary source for my discussion is Alexander F Baillie’s book Kurrachee: Past: Present: and Future., published in 1890. Best categorized as a highly descriptive travelogue, Baillie’s work is one of the very few English language literary sources tracking Karachi’s history during the transformations of the nineteenth century. Intended to serve as an easily accessible collection of facts about the city and port, Baillie uses this work to examine the history, landscape, infrastructure, and culture of Karachi in a very methodical manner. In doing so, he draws upon a number of works from previous authors, official colonial documents, and personal interactions with both local inhabitants and British officers. Essentially serving the purpose of a colonial survey of the city, Baillie’s book provides a lens into the colonial perspectives on Karachi during this era. Using Baillie’s text as a guide, this essay will navigate through British expansionist ideologies in the Indian subcontinent, and the extent to which they contributed towards the emergence of Karachi as a port city through the nineteenth century. By situating Karachi in an age of colonization and industrialization, this paper will track how the combination of these factors led to the development of Karachi’s expansive connectivity, providing an understanding of how the city established itself as a central transit point of the Indian Ocean in the nineteenth century. It will simultaneously examine how the city’s infrastructure and demographic both affected and were affected by Karachi’s growing connectivity. To situate Karachi into a broader context of flowering colonial cities in the nineteenth century, in an attempt to gain a better understanding of the larger factors surrounding Karachi’s transformation, it is important to assess the existing literature on other Indian port cities at the time. The two biggest port cities serving the British Empire in South Asia were Bombay and Calcutta. Given that Bombay also developed from a collection of fishing islands into a cosmopolitan center of connectivity in the Indian Ocean, and that there exists a vast array of literature tracking its emergence, it acts as a uniquely significant reference in examining Karachi’s transformation. In his book Mumbai Fables, author Gyan Prakash explores the rich history of Mumbai from the Portuguese conquests of the sixteenth century up until its establishment as an urban center at the foot of the Indian Ocean in the twentieth century. With a particular focus on the city’s nineteenth century development under British colonial rule, Mumbai Fables serves as an ideal source in understanding how to approach the historiography of an emerging port city under the auspices of colonial authority. Nile Green’s Bombay Islam provides a different perspective on Bombay’s history, with a specific focus on the period between 1840 and 1915. Green’s book is of particular interest for understanding how the industrial elements of steam and print accelerated the growth of cosmopolitanism in a well-connected major port city. With Karachi following a similar trajectory, Bombay Islam becomes an important source for examining how demographic shifts are influenced by industrialization: a key element in Karachi’s own evolution. Lastly, Partha Chatterjee’s The Black Hole of Empire informs of British imperial perspectives on the governance of Indian territories through an examination of a particular event in Calcutta’s history. Given that my primary source is a Britisher’s perspective on Karachi during the period of its colonization, The Black Hole of Empire helps to frame Alexander Baillie’s assessments of the city in the broader context of the prevalent imperialistic perspectives of colonial cities at the time. Karachi Under the Rule of Sindhi Dynasties: This essay begins by outlining the environment of the city during its earlier history, particularly the role of Karachi under Sindhi dynastic rule, which enabled its future growth. Under the Kalhora dynasty, which reigned over Sindh during much of the eighteenth century, Karachi was not considered an financially significant city. Sindh’s main trading center had been Thatta, further north of Karachi where the Indus Delta begins. Thatta had historically been an important city for trade, with accounts of the Mughal Empire establishing a large business linking it with the rest of the country. As recorded by Baillie in his book, according to the compiler of the ‘Gazetteer of Sindh’ during roughly the 1770s the Kalhora’s ceded the city of Karachi to the Khan of Kelat1. While the reason for this exchange has not been mentioned, that Karachi was ceded to another ruler highlights the lack of strategic value it held in the eyes of the Kalhora princes at the time. This is supported by the scarce mentions of Karachi by merchants visiting Sindh during the late eighteenth century, especially those journeying to Thatta. For travelers arriving at Sindh via the Indian Ocean, Manora Island most likely would have served as the disembarkation point and the town of Karachi would have been a transit point for their journey to interior upper Sindh, where Thatta lies. The lack of mentions in travel writings and its cession to another ruler does not, however, mean that the city was indeed unimportant. According to a report published by British Marine Lieutenant John Porter on his visit to ‘Crotchey Town’ in 1774, Karachi “possessed a great trade”. In fact, in 1758 when the British established a factory in Thatta, the supervising agent established communication with Karachi, proof that a trading center existed in the city but was 1 Baillie, Kurrachee, 22. neglected by the ruling Sindhi dynasties2. With their capitals situated in interior Sindh, both the Kalhora and later Talpur dynasties preferred to concentrate their power further inland. As a result, cities such as Hyderabad, Thatta and Sehwan grew in importance while the seaport of Karachi was given little to no assistance in its development. Seeing little value in the business of imports and exports, except for personal luxuries, the ruling dynasties opposed the creation and development of major seaports, likely in fear of their stronghold cities losing importance. However, as Karachi’s trade continued to thrive, the city grew in both area and commercial activity until it could no longer be neglected. In 1795 the city was seized by Karam Ali Talpur and then annexed to the Central Sindh Government, the government of the ruling Talpur Dynasty. Karachi remained under control of the Talpurs until it was occupied by the British in 18393. An understanding of Karachi’s commercial environment during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries helps to discern the functioning of Karachi’s port at the time. It can be reasonably assumed that the local trading center, which had been established by Karachi’s residents, was influential to the extent that it attracted the ruling Talpur dynasty to seize the city. Although the exact number is not recorded, the city was believed to boast a population roughly numbering 6,000. Of these inhabitants, majority were Hindu merchants who had established commercial networks with many neighboring trading centers including Muscat, Kandahar, Multan and Kabul4. The Hindu population were an influential body in Karachi and played an essential role in cultivating the city’s commercial environment. They understood the value of Karachi for mercantilism and had profited off its strategic location. With trade through the internal provinces near the Indus depleting due to government taxes and oppression, all trade between the sea and interior Sindh passed through Karachi. However, the transport of goods 2 Baillie, Kurrachee, 36, 18. Baillie, Kurrachee, 22. 4 Baillie, Kurrachee, 30. 3 from Karachi to Hyderabad and other norther districts, including goods destined for Kabul and Kandahar, was a laborious and taxing journey. Without a direct passage through the Indus River, the trade was conducted partly by boat and partly by camel 5. The tacking of boats on the Indus was both expensive and subject to delays, which resulted in costly and unfavorable trading conditions. Despite these burdens, the local inhabitants capitalized on the thoroughfare nature of the city, seizing the opportunity to increase their revenue, and as a result accelerated the development of Karachi. By allowing itself to serve as a means of connecting foreign markets to established trading centers further north in India, Karachi’s port was able to grow in significance despite the expenses of the journey beyond: by adopting a transitory role. According to a report by Commander Carless in 1837, the annual revenue generated by Karachi’s trade amounted to Rs.2,146,625 of which exports generated Rs.1,599,625. The main exports arrived at Karachi from interior Sindh and consisted of Ghee and Indigo. Karachi’s merchants were effective in setting up trade networks with landlocked cities, facilitating the transfer of goods to the port city and generating their own revenue through taxations. Very few exports were manufactured in Karachi, with gur (raw sugar) and dried fish being the exceptions. This is because the merchants of Karachi understood the local trading environment, and the expenses and limitations of cultivating their own trade market. Instead, they focused on facilitating trade between other markets, a more profitable outcome for both the inhabitants and the city’s port at the time. It was at this junction where Karachi’s communication with the major port city of Bombay may have begun to foster. According to Gyan Prakash’s Mumbai Fables, Bombay was already an established headquarters for the East India Company during the late eighteenth century. With mass immigrations of Parsis, Hindus and Muslims into the city, Bombay quickly became an important and wealthy mercantile 5 Baillie, Kurrachee, 38 community6. The Hindu merchant community in Karachi was aware of these developments and resultingly traded with the British India solely through Bombay. By establishing a trade network with Bombay, Karachi was able to pique the interest of both the Sindhi rulers and the British East India Company. A closer inspection into the trade of opium, which was unquestionably the article which generated the most revenue for Karachi, provides an insight into the dynamic relationship between Karachi and Bombay. Just as with Bombay in the late eighteenth century, Karachi’s utilization of the opium exports had a profound effect on the city’s evolution – with opium exports amounting to Rs.1,600,000 in revenue in 1838. The opium network connected Karachi with merchants from Rajasthan, where the opium was received from, and the Portuguese settlement of Daman, where the opium was shipped to on its way to China7. By bypassing Bombay, which was an established opium exporter, as a destination on this route, Karachi set up a parallel opium trade network which competed with Bombay. Although still operating on a much smaller scale, Karachi’s independent trade route was an indication that it was growing into a competing port city. However, with four fifths of the city’s imports arriving from Bombay, Karachi still had a long road ahead to establish itself as a major port city in the Indian Subcontinent8. In similar fashion to Bombay, Karachi’s development was propelled by the immigration of communities to the coastal city. Albeit at a smaller scale, during the early nineteenth century Karachi was establishing itself as a center for migrants, laborers, merchants, and travelers. The influx of people, coupled with the increasing thoroughfare, had created a shift in the city’s demographic. Karachi was still a small town, with majority of the infrastructure existing in the form of mosques for the Muslim community and temples for the Hindus. Apart from these religious sites, the city was still mostly a collection of 6 Prakash, Mumbai Fables, 36. Baillie, Kurrachee, 39-41. 8 Baillie, Kurrachee, 40. 7 fishermen’s mud huts. However, as the population began to grow Karachi extended into its suburbs and began taking the shape of a larger city. An important contributor to this growth was the slave trade network which had been established in the city. With approximately 600-700 slaves docking at Karachi’s port annually, it not only harbored many slaves but also became a local hub for the transfer of slaves further north towards Thatta and Hyderabad. The largest group of slaves were the Siddees, originally from East Africa and mostly consisting of young children who arrived at Karachi through Muscat. Bought mostly by fishermen, the Siddees soon established themselves as bold and active sailors and also integrated with the local population. As a result, new communities began flowering, including the Guddos, who were the children of Muslim Sindhi men and Siddee women, and the Kambranis, the children of Guddo women and Sindhi men. Another group of slaves, although much smaller in number, were the Hubshees who were brought to Karachi from Abyssinia. Majority of the Hubshee community were women who eventually married into high ranking Sindhi households. By 1837 the slave trade in Karachi had rapidly grown, with at least 1500 slaves arriving from Muscat and East Africa according to British officer Commander Carless 9. With this mass influx, Karachi’s community grew in number and diversified in skill. British Occupation and Industrialization: With both its trade and population accelerating, Karachi was gaining traction as a strategically important city. As a result, the British launched an expedition in 1839 which led to the capture of Karachi. Upon arrival from the sea, the British fleet took control of Manora, an island which was part of what compromised Karachi’s natural harbor, protecting the bay from the open sea. In 1843, British Governor Sir Charles Napier led an attack on the Talpur rulers which resulted in the annexation of Sindh by the 9 Baillie, Kurrachee, 35-36. British Empire10. With the arrival of the British, Karachi underwent further transformation at a rapid pace. Boasting a population of approximately 14,000 inhabitants at the time of its surrender, the city still lacked basic infrastructure. Recognizing the needs of Karachi’s growing population, the British undertook a series of developmental projects, prioritizing the improvement of the city’s harbor. Before its capture, Karachi’s port harbored mostly canoes and dinghies and only 30 sea-faring vessels. As a result, the port did not require the same infrastructure as that of larger cities such as Bombay and Calcutta. Moreover, the town’s connection to the port at Manora was also largely underdeveloped. According to a report by Dr. Lord, a member of the Bombay Medical Service, the ground was comprised entirely of marsh, with no road connecting the two areas and the water between the mudbanks was deep enough only for a canoe to pass through 11. An analysis of Photograph 2, which is a map of the Karachi harbor in 1838 as drawn by Lieutenant Carless, reveals the extent of the town’s disconnect from the port. A narrow and rocky passageway connects Manora Point with Kemari, which is another docking point for arriving vessels. Kemari itself is seen to be largely underdeveloped, with only a small village in its vicinity. The main town of Karachi is still at a distance from Kemari village, with no road connection between the two points. Unlike their British counterparts, the Talpur government did not possess the industrial capabilities needed for dredging out the swampy marsh between Kemari and Karachi’s town. Additionally, with mostly small canoes and dinghies facilitating the transport of people and goods from the docks to the town, there was no urgent need for an investment into the improvements for the connectivity of the port to its town. For any large vessels that were arriving at Karachi, the map shows a passageway through Chinny Creek which connects the open sea directly to the heart of Karachi. However, this passage was only accessible at high tide thereby subjecting the safe docking of these large 10 11 Baillie, Kurrachee, 7-8. Baillie, Kurrachee, 42, 27-28. boats to the natural restrictions of the changing tide. As a result, access to the town from the port was generally considered a difficult undertaking. The decision to undertake improvement’s on Karachi’s harbor was a very important one for the history of the city. Although this step can be seen as the natural progression of Karachi’s development, especially given the profit-driven nature of the British Empire’s government, it would not have been so obvious without the role played by the city’s inhabitants. The shifting dynamics of Karachi’s population was synchronized with the city’s economic evolution. As the trading environment became more established, more migrants began settling in and around the city to the point where the British Empire were willing to invest thousands of pounds into Karachi. Given the state of the harbor at the time of British occupation, the Karachi Harbor Works were seen as a necessity, to fully harness the growing city’s economic potential. A number of projects were outlined by the Governor General of Sindh, Sir Charles Napier, to improve the connectivity of the city to the port as well as the harbor’s capabilities. The most important works included the Napier Mole Bridge, the Manora Breakwater, and the construction of a wooden pier at Kemari. The Napier Mole Bridge was the first suggestion for improvements to Karachi’s harbor, with the aim of constructing a road which would connect the town of Karachi to its port. The construction of such a bridge would bear fruitful returns for the commerce of the city, with a significantly easier route being established between the port and the city for the transport of goods and people. The Napier Mole Bridge was the first step in bringing Karachi’s town into immediate contact with its shipping docks. Completed in 1864, this road connection stimulated a series of projects which significantly contributed towards increasing the connectivity of Karachi. Photograph 3 shows a picture of the completed Napier Mole Bridge, with a collection of goods easily being transported across. This was a significant moment in the course of Karachi’s history, a pivot point off of which Karachi began benefitting from the industrial powers of its British rulers in the form of a symbiotic relationship. The Manora Breakwater was another significant infrastructure project for Karachi’s port. The breakwater was commissioned for the purpose of protecting the bay from the sea, in turn allowing for the year round use of Karachi’s port. Given the more favorable monsoon winds near the Arabian Sea, weather disruptions would not impede the access of Karachi’s port at any time of the year. Construction of the breakwater was completed in 1873, and was considered to be a great engineering attraction at the time. Photograph 4, an image of the breakwater under construction, provides an insight into the scale of the project. A product of industrial progress, construction was facilitated by steam-powered cranes laying concrete blocks over a total length of 1500 feet12. More important were the implications of Karachi’s port bearing the ability to serve as an all season docking point for vessels. This feature is what distinguished Karachi from India’s other major ports of Bombay and Calcutta, which were restricted by the stronger and fiercer monsoon winds. As a result of the breakwater, Karachi was the largest port on the Indian Subcontinent which could facilitate arrivals year round. This significantly enhanced its connectivity to foreign markets and the greater Indian Ocean world. Moreover, it served strategic and military benefits for the British Empire, who now possessed the ability to send military troops into India any time of year. The wooden pier at Kemari was proposed for passengers to disembark at and to form a causeway between Kemari and Karachi. Named ‘Merewether Pier’, the dock also served as a discharge and loading point for large vessels. Completed in 1864, the pier was the first step in the transformation of Kemari, and its growth as a town separate from Karachi’s mainland. Photograph 5 shows the newly constructed 12 Baillie, Kurrachee, 54 passenger landing site at Kemari, a drastic improvement from the sketch of the entrance of Karachi in 1832 depicted in Photograph 1. The rapid progress of these harbor improvement projects naturally accelerated the growth of Karachi’s city as well. Photograph 6 shows the Kemari Wharf, with steam ships at its docks, the perfect illustration of how industrialization influenced Karachi’s development. With an increased connectivity from the port to the town, the ability to harbor steam ships, and a port which was accessible year-round, the British import of industrialization drastically transformed Karachi and its port. With the Karachi Harbor Works developing Karachi’s accessibility via the sea, the Sindh Railway Network aimed to increase Karachi’s connectivity to major cities further inland. In its initial plan, the Sindh Railway aimed to establish a direct railroad connection between the seaport of Karachi and Hyderabad13. However, with a flourishing trade network being established with Punjab, the British government amended the project, re-routing it as the Sindh-Punjab-Delhi Railway. This railway would connect Karachi with Hyderabad, Multan, Lahore, Amritsar and eventually the capital Delhi. An extensive network of major trading cities, the railway project significantly improved upon the previous trade routes of Karachi, which as discussed earlier were long and expensive journeys. With other railway networks, such as the Punjab Northern, connecting to this main line, the whole system was eventually named ‘The North-Western Railway’ in 1885. With an industrial port and a well-established railway network, Karachi became one of the most well connected cities in India. Acting as a thoroughfare route, with direct connections from the Arabian Sea to Delhi, it profited off its strategic location at the foot of the Indian Ocean. 13 Baillie, Kurrachee, 75 In this discussion, it is important to understand British motivations behind these projects. While the colonial government was definitely invested in the development of Karachi, these megaprojects largely stemmed from the expansionist ideologies of the imperialist government. By connecting the major cities of the Indian Subcontinent, the British were trying to exert a more centralized control over the entire country. Greater accessibility translated to more profitability, and as a result a stronger control over their Indian Empire. Additionally, Karachi’s emergence as a major port city in India increased British confidence over a potential expansion into the neighboring Afghan country. Therefore, while the city of Karachi was benefitting from these industrial endeavors, the British government was establishing greater dominance over the region. An examination of Photograph 7 reveals the extent of upheaval Karachi’s harbor and transport network underwent. Depicting the plan of the harbor in 1888-89, this image shows an amalgamation of the infrastructure projects initiated by the British after their annexation of Karachi. In comparison to Photograph 2, Karachi’s harbor plan in 1888-89 is significantly more detailed and complex. Notably, the Manora Breakwater is clearly visible, at the very tip of the map and exposed to the open sea. The passageway between Manora and Kemari is significantly wider, with the imperial government constantly dredging out the marsh and rocks which dominated the topography of the passageway in Photograph 2. This wide and cleared out route to Kemari allows for the arrival of all sizes of vessels to the docking point at the newly constructed Merewether Pier. With the construction of these industrial harbor improvements, arriving vessels were no longer subject to the natural restrictions of changing tides, and passengers could instead easily disembark at Kemari point. Kemari’s connection with Karachi’s town is visibly improved in this harbor plan, with the mangrove dominated marsh no longer hindering the smooth transport of people and goods from the port to the town. The Napier Mole Bridge can be seen, serving as a direct road connection between Kemari and Native Jetty, the closest point of Karachi’s city to Kemari’s docks. Parallel to the Napier Mole bridge is the Napier Mole line, a railway track which runs through Native Jetty, eventually feeding into the North Western Railway. Another railway track runs eastwards from Kemari, towards the eastern quarters of the city, including Clifton and Bath Island, and eventually feeds into the main North Western Railway as well. Compared to Photograph 2, we see an extremely well-connected and infrastructurally developed Kemari, easily accessible via sea and land. When assessed altogether in this map of Karachi’s Harbor in 1888-89, we can visibly determine the influence industrial advents have had on Karachi’s connectivity, and the contributions they have made towards the establishment of Karachi as a major transit point in the Indian Ocean. Demographic Shifts during Karachi’s Modernization: With these major construction projects taking place, the city’s demographic underwent a significant change. The population increased from 14,000 in the 1830s to 56,879 by 1856. This drastic increase was largely due to the increased connectivity of Karachi to different regions. After the development of the North-Western railway, the ease of migration to Karachi was drastically elevated. As a result, communities of Punjabis, Balochis, and Multanis migrated to Karachi from further inland. After becoming the stronghold city of Sindh with a bustling commercial environment, merchants from foreign markets were more keen in establishing agency with Karachi. This led to the migration of Arabs and Persians from the gulf region to Karachi. Through the modernization of its port, Karachi also began gaining traction as a major port city of the Indian Ocean, linking together travelers from all parts of the Indian Ocean world. In his book, Baillie writes of Karachi’s population “there are few cities in India that can furnish a greater admixture of different tribes and different nationalities”, giving an idea of the diversity of Karachi’s demographic 14. The import of industrialization, manifested through the city’s increased connectivity, was bringing with it its associated byproducts: cosmopolitanism and diversity. 14 Baillie, Kurrachee, 88-89. Through the establishment of an industrial market in Karachi, the rural-urban migration of laborers brought a diverse community into the city’s folds. Additionally, the modernizing infrastructure of Karachi was accelerating its progress towards becoming a cosmopolitan hub of the West Indian Empire, in similar fashion to the rise of cosmopolitanism in Bombay discussed in Bombay Islam. This is unsurprising, based on Karachi’s historical embracement of acting as a thoroughfare city. With a constant flow of temporary visitors, its population fluctuated throughout the late nineteenth century. This is best exemplified through the census results of 1856 and 1872. Boasting a population of 56,879 in 1856, after 16 years the census of 1872 showed a decrease in the total number of inhabitants in the city, with the official population stated as 56,753. This retrograde in numbers is best explained by the large proportion of temporary visitors forming the city’s demographic. The fluctuating population speaks to the deep embracement of the city as a transit point on the foot of the Arabian Sea. Karachi serves as a facilitator of trade, with merchants from inland India and foreign markets frequenting the port city in attempts of expanding their commercial networks temporarily settling in the city. However, the next census of 1881 counted the population at 73, 560. Therefore, while there was a fluctuation of the population due to temporary visitors, the permanent residents of Karachi were still growing in numberwhich can be attributed to the infrastructural upheaval of the city, attracting inhabitants to permanently reside in the city. The infrastructural developments of the mid nineteenth century therefore clearly played a role in shaping the city’s community, and due to the strength of this established population, further developmental works were commissioned by the British government to establish Karachi as a major city in the British Empire. The growth of Kemari into an established quarter of the city can be seen as a product of its improved accessibility. Baillie mentions of his surveys of Kemari in the 1880s that “there are numerous offices and warehouses which are now being widely extended” as a result of the railway lines originating at Kemari15. With more offices came the construction of living quarters for officers working in Kemari, in turn bringing a drinking bar and church to the land. This eventually led to the establishment of a native village, which with it brought the essential commodities of a town into Kemari’s area, including a hospital, restaurants and a small market. The evolution of Kemari into a functioning town was a direct result of the industrializing landscape which was looming over Karachi. Kemari serves as just one example of a variety of different areas in the city which underwent similar transformations, from sparse villages to organized quarters of a larger metropolis. British modernization was transforming the topography and demographic of the city. The rapidly growing community of Karachi necessitated public infrastructural development to address the needs of the cities inhabitants. It must be noted here that the British government was particularly skilled in such work, and organized Karachi into a modern and planned city quite effectively. The area of Karachi was roughly 3200 acres in size and formed the shape of a triangle, with the Customs House at the city’s apex towards the south and the base extending from the Frere road to the Government Gardens. On the west side the Lyari river formed one end and to the east the North-Western Railway. This compromised the main area under the Municipal district. South of the Municipal district were the areas of Kemari, Manora, Bhit and Baba which fell under authority of the Port Trustees. As the population began to spread out across the city, quarters of governance were established to easier maintain the administration of Karachi. Of these Saddar Bazaar, Old Town, Clifton, Kemari, and Frere Town were the most populous16. Photograph 8, taken from Baillie’s book, is a map of Karachi’s quarters drawn after a survey of the city in 1870. The city’s boundaries under the municipality’s administration 15 16 Baillie, Kurrachee, 81. Baillie, Kurrachee, 87-88. can easily be seen, with the Lyari river on the west side, the boundary line on the south separating the municipality from the Port Trustees and the North-Western railway on the eastern front. On one bank of Lyari river lies Old Town, a populous quarter, where the Sindh Cotton Press is located. This quarter was largely populated by laborers who worked in the nearby factories. The Queens Road Quarter was a newly established quarter at the time of Baillie’s writing, another well-populated district at the southern base of the city. North of the Queens Road Quarter is the Railway Quarter, which is where the Kemari railway branches connected to the main North-Western Railway network. The Railway Quarter was dominated by government offices, including the Municipal Office. East of the Railway and Queens Road Quarter is the Saddar Bazaar and Napier Quarter. These were the wealthier districts of the city, where most of the Europeans resided, and the architecture of these quarters was dominated by Victorian style buildings, including the famous Frere Hall and Empress Market. Also located in these localities was the Government House of Karachi, the main administrative center of the city. As a result, much of Karachi’s commercial activity was centered around the Saddar Bazaar and Napier Quarter. To the north of the city lie the Civil Lines and Soldiers’ Bazaar. The northern districts of the city were populated mostly by migrants from interior Sindh and Northern India, who had settled in the industrial center of Sindh in search of labor and trading opportunities. The map of Karachi therefore reveals the demographic breakdown of Karachi, and how the different quarters have been characterized by the infrastructure and inhabitants which dominate them. An analysis of the photograph is telling of how British modernization has influenced demographic shifts in Karachi’s growing population, and how those shifts have characterized the city’s topography. It shows how Karachi has developed into an organized and functioning major colonial city in the Indian Empire, swiftly functioning to best serve the colonizers financial needs. Karachi’s demographic organization is an example of colonial impositions of city planning and modernization in the Indian Empire, dividing Karachi into different quarters in order for it to function as a colonial ‘model town’. Trade, Bazaars, and Public Infrastructure: Saddar Bazaar was the chief market of Karachi, where the best goods could be found. Bazaars had always been a staple of large cities in the Indian Subcontinent, and Karachi’s Saddar was not very different. However, the architecture of Saddar and Napier Quarter was donned by grand European-style buildings built by the British government. Empress Market, named in honor of Queen Victoria’s jubilee year, was the centerpiece of the Saddar Bazaar, and the Frere Hall, named after Sindh’s governor general Sir Henry Bartle Frere, was also a defining building of Karachi, although primarily used for European gatherings. That the iconic buildings of Karachi were named after colonial authorities is telling of how imperialist perceptions of superiority infiltrated the city’s public infrastructure. These buildings, in the heart of Karachi’s town, were representative of the colonial environment which brewed throughout the city. Along with the Government House and the Trinity Church, these buildings dominated the architecture of Saddar Town: a district deeply influenced by Victorian styles. The Saddar Bazaar served as the civilian and military center of Karachi, expanding in area to match the city’s growing population. Saddar’s evolution was largely stimulated by the reversal of a decree in 1842 which had previously been established by the ruling Sindhi Amirs prohibiting the inhabitants of Karachi from settling in the Bazaar. With a growing population, Karachi’s Saddar district was soon densely populated by the city’s inhabitants shrouding the town’s civilian center. In Photograph 9 we are shown a picture of the outlay of the bazaar, with the Empress market tower protruding in the top right hand corner. Photograph 10, which is a picture of Hyderabad around the same time, is attached here to show how differently Karachi developed as compared to Sindh’s other major city. The architecture is very revealing of the extent of the British’s involvement in the governance of the city, with Karachi clearly being prioritized for investment, an acknowledgement of the city’s economic potential. The Hyderabad Bazaar is dominated by characteristic clay roof homes, urban density, and narrow streets, all indicative of pre-industrial city development. In comparison, the image of Saddar Bazaar shows the extent of British influence in the city, with British style houses, wider streets, and urban greenery serving as examples of imperial influence on Karachi’s urban landscape. With its increased development, Karachi had become the center of power in Sindh, and the migration of populations from interior Sindh to the southern city is indicative of the power shift. European and Arab travelers began to settle in the bustling city of Karachi instead of Hyderabad, where they would have previously journeyed to. By the late nineteenth century, Karachi had undergone many structural changes to facilitate the growing number of inhabitants, an official census in 1890 numbering them at 84,50017. What began as a collection of small islands had been transformed into an organized, developed, and populous commercial hub. With the city now bearing an extensive transportation network, a review of the port’s trade aids our understanding of how industrialization has fueled the emergence of Karachi as a major port city in India. In his book Baillie describes Karachi as “ a town situated on a port of transit, which takes such supplies as it may require for its own use and consumption, but only acts as an agent for other communities of Sindh and Punjab.”18 Baillie’s assessment emphasizes Karachi’s thoroughfare nature, and the preference of its merchants for acting as agents for other trade markets instead of establishing an independent commercial market of the city. As a result, Karachi was unable to fully compete with the ports of Bombay and Calcutta, each of which possessed a vibrant and thriving stock of frequently traded market goods leading to a more spontaneous or large trade order being processed at their ports instead of Karachi’s. In this regard, Karachi served as the alternate cheaper, and usually nearer, shipping route for smaller orders. However, Karachi’s transitory nature still afforded it a thriving commercial environment, one which managed to offer some competition to both Bombay and Calcutta. Through its port have 17 18 Baillie, Kurrachee, 89. Baillie, Kurrachee, 237. passed thousands of tons of metal for the construction of the North-Western Railway, as well as thousands of tons of wheat, rapeseed, and cotton for shipment to foreign markets. Through an investigation of Punjab’s imports and exports we are able to unwrap the dynamics of Karachi’s commercial environment. According to statistics collected by Baillie, Karachi accounted for 17% of Punjab’s exported goods in 1888, whereas Bombay accounted for only 8.5% and Calcutta 10.2%. Despite the closer proximity of Karachi to Punjab, that it exported almost double the amount of Punjabi goods compared to Bombay and Calcutta indicate that the port city had clearly benefitted from a modernized port, and could compete with the other major shipping centers of India. These figures provide evidence of Karachi’s emerging role as a main transit point in the Indian Ocean. However, in terms of Punjab’s imports Karachi still lagged behind Bombay and Calcutta who accounted for 23.3% and 25.4% of the imports in 1888 respectively. In comparison, Karachi only accounted for 21.0% 19. This is due to Karachi’s inability to supply Punjab with its desired goods to the same extent of Bombay and Calcutta, which stems from the city’s preference for acting as an agency for trade over establishing its own market. As a result, without its own market of goods, if the desired stock was not passing through the port, Punjab could not rely on Karachi for its necessary imports. This explains why Karachi has not yet overtaken Bombay and Calcutta in supplying Punjab with its imported goods. While it is certainly an emerging competitor for Bombay and Calcutta, Karachi’s embracement of a throughfare city acts as a limiting factor for its commercial capabilities. Conclusion: It is evident that a number of different factors contributed to Karachi’s evolution from a fishing village to a major port city of the British Empire. This paper unravels Karachi’s expanding connectivity, investigating how the import of industrialization accelerated the growth of an emerging port city to 19 Baillie, Kurrachee, 239-240. create a major transit point in the Indian Ocean world. Functioning primarily as a transit city for facilitating trade in the early nineteenth century, Karachi grew into not only the headquarters of Sindh, but also one of the largest cosmopolitan centers of the Indian Empire. With the North-Western Railway creating a direct line of transport between Karachi and Punjab’s major trade networks, and extending to Delhi, the city’s port was able to facilitate a large volume of trade with established foreign markets. The Karachi Harbor Works dramatically improved the port’s accessibility, and distinguished Karachi from other major ports through the ability to accommodate arriving vessels year round. With the emergence of a modern port, Karachi was more connected to the greater Indian Ocean world, bringing a wider array of people, goods and cultures into the city. This increased connectivity resulted in demographic shifts in the city’s urban environment. An increasing influx of both foreign and local communities into its vicinity requisitioned Karachi’s public infrastructural development. As a result, colonial projects transformed both the civilian and financial landscapes of the city, with Karachi benefitting from the global period of modernization. The combination of its strategic location, its attractive community, and its extensive network of connectivity enabled Karachi to create its own identity: a social, cultural, and economic hub at the foot of the Indian Ocean. The age of industrialization harbored Karachi’s embracement of a transit city, and this paper explores how Karachi benefitted from the adoption of such a role. Understanding this period of Karachi’s history lays the foundation for tracking its development in the twentieth century, when the city broke out of its self-constructed shell of thoroughfare and progressed into the modern day metropolis it exists as today. Photograph 1: A pencil drawing of the entrance of Karachi from the sea. This image was taken from The British Library Exhibition: Asia, Pacific, and Africa Collections; Item number 247. It is a pencil drawing by George Boyd dated between 1821 and 1844. It is titled ‘Entrance to Kurrachee from the Sea.’ The drawing is of Boyd’s 95 mainly of landscapes and monuments in the Deccan, West India, and Afghanistan. Photograph 2: A hand-drawn map of Karachi’s Harbor in 1838. This image is taken directly from Alexander Baillie’s Kurrachee: Past: Present: and Future. It shows an annotated drawing of Karachi’s harbor by British Naval Lieutenant Carless in 1838. Photograph 3: Napier Mole Bridge in the 1890s. Taken from the British Library Exhibition: Asia, Pacific, and Africa Collections; Item number 8. This photograph is taken by an unknown photographer, from an album of 46 prints titled ‘Karachi Views’. It depicts the Napier Mole Bridge, an iron bridge which connected Karachi to Kemari. Photograph 4: Construction of Manora Breakwater 1872. This image is part of the Crofton Collection: ‘Public works including the Manora Breakwater and the River Son canal system’. The photograph is an archive from the British Library Exhibition: Asia, Pacific, and Africa Collections; Item number 96219. Taken in 1872 by an unknown photographer, it shows the Manora Breakwater under construction. Photograph 5: Passenger landing pier at Kemari, 1890s. This image is taken from the British Library Exhibition: Asia, Pacific, and Africa Collections; Item number 6. It is also part of the album of prints titled ‘Karachi Views’. The photo captures the Merewether Pier, with passenger boats docked at the wooden landing pier. Photograph 6: Kemari Wharf in the 1890s. This image is also taken from the British Library Exhibition: Asia, Pacific, and Africa Collections; Item number 5. It is included in the album of prints titled ‘Karachi Views’ as well. This image portrays the Kemari Wharf, with steam boats docked at the wharf. The railway tracks connecting the wharf to the city can also be seen. Photograph 7: Karachi Harbor Plan 1888-89. Taken from Alexander Baillie’s Kurrachee: Past: Present: and Future. This image is a hand-drawn plan of Karachi’s harbor which was part of the Port Engineer’s Administration Report for 1888-89. It is a highly annotated map detailing the various transport links and infrastructure projects of Karachi’s harbor in the late 1880s. The map also includes a small part of Karachi’s town. Photograph 8: Map of Karachi’s quarters in 1869-70. This image is taken from Alexander Baillie’s Kurrachee: Past: Present: and Future. It is a map of Karachi, aiming to show the boundaries of the various quarters of the city. Drawn after the Survey of Kurrachee in 1869-70, the image is a detailed depiction of the city of Karachi. It includes the prominent buildings of each quarter as well as the city’s main roads and railway lines. Photograph 9: Saddar Bazaar in the late nineteenth century. This image is part of the British Library Exhibition: Asia, Pacific, and Africa Collections; Item number 24. It is included in the collection of photos titled ‘Karachi Views’. The image shows an overhead view of Karachi’s Saddar Bazaar: the civilian and military center of the city. In the top right corner of the image is Karachi’s Empress Market, the main tower can be seen protruding out of the Bazaar towards the sky. Empress Market was Karachi’s finest and busiest market in the nineteenth century. Photograph 10: A street in Hyderabad in the 1890s. Taken by an unknown photographer in the late 1890s, this image is archived in the British Library Exhibition: Asia, Pacific, and Africa Collections; Item number 37. It shows an elevated view of a street in Hyderabad. The image captures a noteworthy feature of Hyderabadi architecture, the triangle shaped windcatchers on the rooftops of the homes. These are known as Badgirs, and help to channel cool breezes into the homes. The photograph is part of an album of 91 works compiled by British engineer P. J. Corbett. Bibliography Primary Sources: Baillie, Alexander F. Kurrachee: Past: Present: and Future. Thacker, Spink, and Co., Calcutta; Thacker and Co., Limited, Bombay; Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent and Co., Limited, London, 1890. “Main Catalogue: Karachi.” Exhibition: Asia, Pacific, and Africa Collections. British Library. Accessed March 27th 2022. http://explore.bl.uk/primo_library/libweb/action/search.do?mode=Basic&vid=BLVU1&vl(freeText0)=kar achi&fn=search&tab=website_tab&. Secondary Sources: Prakash, Gyan. Mumbai Fables. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010. https://doiorg.ccl.idm.oclc.org/10.1515/9781400835942 Chatterjee, Partha. The Black Hole of Empire: History of a Global Practice of Power. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012. https://doi-org.ccl.idm.oclc.org/10.1515/9781400842605 Green, Nile. Bombay Islam : The Religious Economy of the West Indian Ocean, 1840-1915. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.