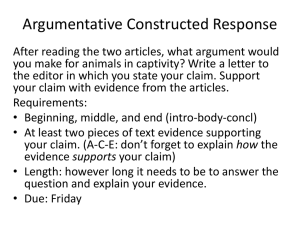

How Does Captivity Affect Wild Animals? Most experts agree it depends on the species, but much evidence shows large mammals suffer under even the best human care. By Cody Cottier, Discover Magazine, Aug 7, 2021 10:00 PM For much of the past year and a half, many of us felt like captives. Confined mostly within monotonous walls, unable to act out our full range of natural behavior, we suffered from stress and anxiety on a massive scale. In other words, says Bob Jacobs, a neuroscientist at Colorado College, the pandemic gave us a brief taste of life as lived by many animals. Though anthropomorphism is always suspect, Jacobs observes that “some humans were quite frustrated by all that.” This is no surprise — we understand the strain of captivity as we experience it. But how do animals fare under the same circumstances? Putting aside the billions of domesticated livestock around the world, some 800,000 wild or captive-born animals reside in accredited American zoos and aquariums alone. Many people cherish these institutions, many abhor them. All want to know: Are the creatures inside happy? Signs of Stress Happiness is hard to judge empirically, but scientists do attempt to quantify welfare by measuring chronic stress, which can arise as a result of restricted movement, contact with humans and many other factors. The condition reveals itself through high concentrations of stress hormones in an animal's blood. These hormones, called glucocorticoids, have been correlated with everything from hair loss in polar bears to reproductive failure in black rhinos. 1 That said, it’s difficult to say what a normal level of stress is for any given animal. An obvious baseline is the captive’s wild counterpart (which surely has its own troubles, from predation to starvation). But the problem, says Michael Romero, a biologist at Tufts University, “is that there’s just not enough data.” Given the challenge of measuring a wild animal’s stress — the requisite capture isn’t exactly calming — few such studies have been undertaken, especially on large animals. Besides, hormones may be an imperfect gauge of how agitated an animal really feels. “Stress is so complicated,” Romero says. “It’s not as well characterized as people think.” So researchers can also look for its more visible side effects. Chronic stress weakens the immune system, for example, leading to higher disease rates in many animals. Opportunistic fungal infections are the leading cause of death in captive Humboldt penguins, and perhaps 40 percent of captive African elephants suffer from obesity, which in turn increases their risk of heart disease and arthritis. Another sign of stress is decline in reproduction, which explains why it’s often difficult to get animals to breed in captivity. Libido and fertility plummet in cheetahs and white rhinos, to name two. (A related phenomenon may exist in humans, Romero notes: Some research suggests that stress, even when breeding does succeed, high infant mortality rates plague some species, and many animals that reach adulthood die far younger than they would in the wild. The trend is especially poignant in orcas — according to one study, they survive just 12 years on average in American zoos; males in the wild typically live 30 years, and females 50. Big Brains, Big Needs Our wild charges don’t all suffer so greatly. Even in the above species there seems to be some variability among individuals, and others seem quite comfortable in human custody. “Captive animals are often healthier, longer-lived and more fecund,” writes Georgia Mason, a behavioral biologist at the University of Ontario. “But for some species the opposite is true.” anxiety and depression can reduce fertility.) Romero emphasized the same point in a 2019 paper: the effect of captivity is, ultimately, “highly species-specific.” In many ways it depends on the complexity of each species’ brain and social structure. One decent rule of thumb is that the larger the animal, the worse it will adjust to captivity. Thus the elephant and the cetacean (whales, dolphins and porpoises) have become the poster children of the welfare movement for zoo animals. Jacobs, who studies the brains of elephants, cetaceans and other large mammals, has described the caging of these creatures as a form of “neural cruelty.” He admits they are “not the easiest to study at the neural level” — you can’t cram a pachyderm into an MRI machine. But he isn’t bothered by this dearth of data. In its absence, he holds up evolutionary continuity: the idea that humans share certain basic features, to some degree, with all living organisms. “We accept that there’s a parallel between a dolphin’s flipper and the human hand, or the elephant’s foot and a primate’s foot,” Jacobs says. 2 Likewise, if the brain structures that control stress in humans bear a deep resemblance to the same structures in zoo chimps — or elephants, or dolphins — then it stands to reason that the neurological response to captivity in those animals will be somewhat the same as our own. That, Jacobs says, is borne out by a half century of research into how impoverished environments alter the brains of species as varied as rats and primates. Abnormal Behavior Not all forms of captivity are equally impoverished, of course. Zookeepers often talk about “enrichment.” Besides meeting an animal’s basic material needs, they strive to make its enclosure engaging, to give it the space it needs to carry out its natural routines. Today’s American zoos generally represent a vast improvement over those of yesteryear. But animal advocates contend they will always fall short of at least the large animals’ needs. “No matter what zoos do,” Jacobs says, “they can’t provide them with an adequate, stimulating natural environment.” If there is any doubt as to a captive animal’s wellbeing, even the uninformed zoogoer can detect what are perhaps the best clues: stereotypies. These repetitive, purposeless movements and sounds are the hallmark of a stressed animal. Elephants sway from side to side, orcas grind their teeth to pulp against concrete walls. Big cats and bears pace back and forth along the boundaries of their enclosures. One survey found that 80 percent of giraffes and okapis exhibit at least one stereotypic behavior. “Stress might be hard to measure,” Jacobs says, “but stereotypies are not hard to measure.” Proponents are quick to point out that zoos convert people into conservationists, and occasionally reintroduce endangered species to the wild (though critics question how effective they truly are on these fronts). Considering their potential to bolster the broader conservation movement, Romero suggests an ethical calculation might be in order. “Maybe sacrificing a few animals’ health is worth it,” he says. Wherever these moral arguments lead, Jacobs argues that “the evidence is becoming overwhelming” — large mammals, or at least many of them, cannot prosper in confinement. The environmental writer Emma Marris concludes the same in Wild Souls: Freedom and Flourishing in the Non-Human World. “In many modern zoos, animals are well cared for, healthy and probably, for many species, content,” she writes, adding that zookeepers are not “mustache-twirling villains.” Nevertheless, by endlessly rocking and bobbing, by gnawing on bars and pulling their hair, “many animals clearly show us that they do not enjoy captivity.” 3