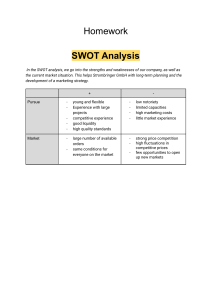

SWOT analysis to evaluate the programme of a joint online onsite

advertisement

Evaluation and Program Planning 54 (2016) 41–49 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Evaluation and Program Planning journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/evalprogplan SWOT analysis to evaluate the programme of a joint online/onsite master’s degree in environmental education through the students’ perceptions Miguel Romero-Gutierrez, M. Rut Jimenez-Liso *, Maria Martinez-Chico University of Almeria, Spain A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Received 5 March 2015 Received in revised form 1 September 2015 Accepted 2 October 2015 Available online 22 October 2015 This study shows the use of SWOT to analyse students’ perceptions of an environmental education joint master’s programme in order to determine if it runs as originally planned. The open answers given by students highlight the inter-university nature of the master’s, the technological innovation used as major points, and the weaknesses in the management coordination or the duplicate contents as minor points. The external analysis is closely linked with the students’ future jobs, their labour opportunities available to them after graduation. The innovative treatment of the data is exportable to the evaluation of programmes of other degrees because it allows the description linked to its characteristics and its design through the students’ point of view. ß 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Evaluation SWOT analysis Environmental education joint master’s degree Onsite-online teaching 1. Introduction The significance of the evaluation of programme effectiveness is becoming an important and recurring research area of Environmental Education (in advance, EE), as evidenced by the inclusion of specific sections and the huge number of studies in high-impact journals. The main topics of EE evaluation could be organised in terms of evaluations of higher education EE programmes (Aznar Minguet, Martinez-Agut, Palacios, Piñero, & Ull, 2011; Goldman, Yavetz, & Pe’er, 2006; Hurlimann, 2009), programmes that seek to build environmental literacy (Bowe, 2015; Van Petegem, Blieck, & Boeve-De Pauw, 2007; Wesselink & Wals, 2011) and related EE outcomes in non-university participants (Rivera, Manning, & Krupp, 2013; Smith-Sebasto, 2006). We can draw some reasons from McNamara (2008) about the utility of programme evaluation to highlight the need to develop a programme evaluation. This is because programme evaluation can: - Understand, verify, or increase the effectiveness of the education. Too often, coordinators rely on their own instincts and passions * Corresponding author. E-mail addresses: miyanke@gmail.com (M. Romero-Gutierrez), mrjimene@ual.es (M.R. Jimenez-Liso), maria.martinez.chico@gmail.com (M. Martinez-Chico). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2015.10.001 0149-7189/ß 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. - - - - to conclude what the students really need and whether the education and management services are providing what is needed. Over time, they find themselves guessing about what would be a proper decision, and use trial and error to decide how new products or services could be delivered. Improve delivery mechanisms to be more efficient. Evaluations can identify programme strengths and weaknesses to improve the programme. Verify that ‘‘you’re doing what you think you’re doing’’. Typically, plans about how to deliver a proper education end up changing substantially as those plans are put into place. Evaluations can verify if the programme is really running as originally planned. Facilitate management’s thinking about what its programme is all about, including its goals, how it meets those goals, and how it will know whether it has met them. Produce information or verify data that can be used for communicating and sharing results. Fully examine and describe effective programmes for duplication elsewhere. The research literature on the evaluation of EE programmes has mainly focused on the evaluation of attitudes, knowledge, competences, and behaviours of the participants in these programmes (Duvall & Zint, 2007; Negev, Sagy, & Garb, 2008; Ponce Morales & Tójar Hurtado, 2014; Perales-Palacios, BurgosPeredo, & Gutiérrez-Pérez, 2014; Smith-Sebasto & Semrau, 2004), or the impact of these programmes on their surrounding 42 M. Romero-Gutierrez et al. / Evaluation and Program Planning 54 (2016) 41–49 environment (Ernst & Theimer, 2011; Gutiérrez-Pérez, OjedaBarceló, & Perales-Palacios, 2014; Powers, 2004; Ruiz-Mayen, Barraza, Bodenhorn, & Reyes-Garcia, 2009). That impact is also evaluated in function on the duration of the EE programmes: even if these programmes are short-term (Tarrant & Lyons, 2011) or long-term (Engels & Jacobson, 2007; Overholt & MacKenzie, 2005). The huge progress in EE programme evaluation has even generated its own theoretical models, such as the logical model (Lisowski, 2006). Although it is not the main objective of our work, we have found an study to bear in mind for future papers about effectiveness between digital and traditional programmes (Aivazidis, Lazaridou, & Hellden, 2006); even an online evaluation consultant (Education Evaluation Resource Assistant or MEERA) is offered to support environmental educators’ programme evaluation activities (Zint, Dowd, & Covitt, 2011). In spite of this abundance of evaluation of EE programmes, Carleton-Hug and Hug (2010) suggest that it is necessary to bridge the gap between the potential for high quality evaluation systems to improve EE programmes and actual practice as the majority of these EE programmes. Most of these researches use multi-choice questionnaires (Aypay, 2009) or Likert scale surveys about aspects related to the teaching for the faculty’s evaluation, such as the implementation of their teaching duties, planning, and teaching methodology (organisation, resources, explanation). A common measurement concerns included small sample sizes, vaguely worded survey items, unaccounted-for confounding factors, and social desirability bias — i.e. the case in which respondents select the answer they feel the surveyor is seeking, rather than that reflecting their true feelings (Stern, Powell, & Hill, 2014). Therefore, as DarlingHammond (2006) state, it is necessary to increase the amount of tools to analyse both prospective educators’ learning and institutions’ responsibility for developing their training. In particular, Erdogan and Tuncer (2009) try to evaluate a course offered at the Middle East Technical University (Ankara, Turkey) to improve its schedule by means of the needs and pertinent problems as expressed by the students using different data collection instruments: need assessment questionnaire, observation schedule for formative evaluation, open-ended questionnaire for formative evaluation (student opinions), and summative evaluation questionnaire. In a recent review of EE evaluation research, Stern et al. (2014) note that most published EE evaluation research represents utilisation-focused evaluation (Patton, 2008) and summative evaluation (Carleton-Hug & Hug, 2010; Erdogan & Tuncer, 2009). Each of these evaluation approaches tends to focus on the unique characteristics and goals of individual programmes. Utilisationfocused evaluations, along with the emergence of participatory evaluation approaches, often develop unique measures of outcomes based on the goals of a particular programme, limiting the direct comparability of outcomes across studies (Stern et al., 2014). As Jeronen and Kaikkonen (2002) show that the teachers, pupils, and parents should participate in the evaluation processes as a ‘‘house model’’, developing senses and emotions. From the pedagogical point of view, process and product evaluation in authentic situations made by the individuals themselves, their peers, and teachers could be useful to support individuals and groups to approach the set goals (Jeronen, Jeronen, & Raustia, 2009). A participatory approach to evaluation provides a strategy for overcoming many of the challenges associated with initiating and sustaining evaluation within an organisation. In order to extend the range of tools and improve the development of an EE programme, we have applied a SWOT (an acronym for strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis, a general tool that can be used to assist faculty to initiate meaningful change in a programme, designed to be used in the preliminary stages of decision-making and as a precursor to strategic planning in various kinds of applications (Balamuralikrishna & Dugger, 1995; PeralesPalacios et al., 2014). This study assumes some aspects from utilisation-focused evaluations with a participatory approach with the long-term aim of promoting improvements in the master’s organisation through the students’ own perceptions. Master students’ perceptions expressed in terms of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats represent a valuable body of information, based on their own experience, to identify possible steps related to the running of the programme, i.e., relate to the common goals, planning (the process of choosing activities and identifying appropriate individuals to be involved in the activities), monitoring (tracking the effect of the programme activities), the organisation and cooperation of the staff. In this paper, we contribute with the SWOT analysis and data processing developed as exportable tools to assess educational programmes, thus enriching the variety of available tools. The outcomes obtained by the implementation of a SWOT analysis will serve as the basis to design a Likert scale questionnaire, a new evaluation instrument that will allow assign weights to the different main issues suggested by the participants in their responses. In this way, we will consider more than the identification of the presence or absence of an issue in the master’s degree evaluation, helping us to improve its development in future works. 2. The SWOT analysis: a strategic analysis tool for evaluating EE programmes As classroom assessment should involve active participation between the students and the educators (Orr, 2013), and stakeholders are interested in evaluation planning, designing, data collecting, and results interpretation, this approach is able to engage programme staff — both educators and students. If the goal of the evaluation only was to understand people’s satisfaction with a particular programme, a simple cross-sectional survey or interview, for example, would suffice (Powell, Stern, & Ardoin, 2006). However, if the evaluation’s goal is to gather and analyse all the contributions from each participant, understand deeply their perceptions, and draw operational conclusions on the programme development, a SWOT analysis could be a more effective option. In the self-evaluation processes for the development of the strategic plan, it is common to use a tool that comes from the business world (Ghemawat, 2002), the SWOT analysis. Besides increasing the enrolment into some universities (Gorski, 1991), its application has a repercussion in evaluation research. For example, using a SWOT analysis, Jain and Pant (2010) evaluate the environmental management systems of educational institutions. Danca (2006) describes how a SWOT analysis works as a straightforward model that provides direction and serves as a basis for the development of marketing plans, accomplishing by assessing an organisation’s strengths (what an organisation can do) and weaknesses (what an organisation cannot do) in addition to opportunities (potential favourable conditions for an organisation) and threats (potential unfavourable conditions for an organisation). SWOT analysis is an important step in planning, and its value is often underestimated due to the simplicity in the creation of the tool (Orr, 2013). For a better understanding of the SWOT analysis, we define each item: - The strengths refer to the things the participants perceive really work. To identify the strengths, we consider the areas where others view the organisation or programme as doing well. M. Romero-Gutierrez et al. / Evaluation and Program Planning 54 (2016) 41–49 - Weaknesses refer to the things the organisation (the master’s degree) needs to improve, such as weaknesses in resources or capabilities that hinder the organisation from achieving a desired goal. By understanding the weaknesses, we can focus on specific areas we need to improve. - Opportunities and threats are outside factors or situations that exist that may affect the organisation in a positive way (or negative way in the case of threats) in achieving a desired goal, as well as trends that the organisation could take advantage of. Examining the trends is helpful in identifying opportunities. 43 Table 1 Number of students per university and course. Universitya 2009–2010 2010–2011 2011–2012 UAL UCA UCO UMA UGR UPO 3 8 6 14 – 4 8 10 7 11 8 7 11 15 12 11 13 12 Total 35 51 74 a This paper reports and discusses the students’ perceptions answered through a SWOT analysis to evaluate the programme of a joint master of environmental education in order to determine how the programme is perceived by the participants. Focusing in the potential of mixed methods for evaluating complex and wideranging educative programmes (Costa, Pegado, Ávila, & Coelho, 2013) the creation of a credible, adaptable, and sustainable system to assess the inputs from the student participants, outcomes of the SWOT analysis implementation can promote clarification of organisational goals and how to achieve them, enhanced organisational commitment from staff, professional development, and new prospects for adaptive management. The following research questions were addressed accordingly: - Related to the perceptions of students as far as a master’s degree in EE is concerned: 1. What do the students perceive really works and what does the organisation (the master’s degree) need to focus? 2. What are the factors or situations that exist that may affect the organisation in a positive or negative way? - Related to the prospective improvements in programme, i.e., planning, organisation, and cooperation of the staff that the students consider: 3. Which issues are identified by the participants, and so they will be useful to develop a deeper evaluation of the master’s degree? - Related to the data collection analysis: 4. Could an easy data treatment be possible that allows for the comparison of students’ perceptions per university in relation to the SWOT analysis of the master’s programme? This study is a step towards the development of a Likert type scale questionnaire to assign weights to frequency counts as if a higher count of the existence of each code actually means that the issue is more important than others in a valid way of determining the strength of each occurrence. Finally, such as an agenda for future work, some challenges rise from this paper, as a comparison between the perceptions of students and teachers in relation to the SWOT analysis (RomeroGutierrez, Martinez-Chico, & Jimenez-Liso, 2015). 3. Methodology 3.1. Context and sample of the study: a joint master’s degree in EE The above-mentioned SWOT analysis was applied to the joint master of environmental education at the end of the academic year 2011–2012 (in its third edition). It is a postgraduate degree adapted to the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) 60 ECTS1 credits. This online-onsite joint master’s degree in EE (75% onsite) is developed simultaneously in six Andalusian universities (Spain) through live online-teaching systems (Adobe1 ConnectTM) combined with a 1 European Credit Transfer System, 1 ECTS= 25 h of student work (7.5 h onsite classes). Universities of Almerı́a (UAL), Cádiz (UCA), Córdoba (UCO), Granada (UGR), Málaga (UMA), and Pablo Olavide (UPO). Moodle platform (25% online). Thus, it provides the master’s faculty of EE for the six sites, avoiding duplication of lessons and the economic cost that would entail the mobility2 of teachers and students, whose number in increasing each edition, as shown in Table 1. The master’s in EE is comprised of three modules: The common module (28 ECTS) offers the basic training for students during the first semester with seven compulsory subjects of 4 ECTS each. The specific module (12 ECTS) is comprised by the subjects of both training itineraries of this master’s. Each training itinerary is justified by the two profiles it is intended for, one of them professional and the other one for research. The student must select one of these two itineraries. Each training itinerary has two obligatory subjects and two optional ones of four ECTS (of which only one is to be chosen). The application module has 20 ECTS, 10 of which are dedicated to the ‘‘internship in companies and institutions’’ for the professional profile, and ‘‘field research in companies and institutions’’ for the research profile. The other 10 ECTS are for the ‘‘end of master dissertation’’ dedicated to analysis and reflection about education practice in formal or nonformal contexts, while in the research profile it is about a field research project. The degree has been configured so, once completed, students may obtain a specialisation: Professional or Research. This master’s is a pioneer experience within the European area of higher education. After three years of implementation and adjustment, we have considered it necessary to evaluate it through the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) developed by the participants. 3.2. Data collection instrument and procedure: a SWOT analysis We designed an online SWOT open-questions questionnaire. In the case of programmes operating on a limited budget, a common impediment to the adoption of an evaluation like it is the cost of evaluation (Powell et al., 2006), but it could be solved by using this SWOT analysis as this avoids the use of any paper and ink for printing the open-questions questionnaires. We obtained 44 students submitted questionnaires it represents the 59.45% of the total students but the 72.13% of those who finished the course, a total of 51 students because of different difficulties, as a previous phase for the questionnaire we do not consider this number as important as the questionnaire’ sample. The comparison of the frequencies of answers in each section of the SWOT in different scales (general and considering each university) allows us to identify the students’ perceptions related to the organisation of the master’s degree and the comparison between universities’ student perceptions in relation to the programme as was planned — i.e. the 2 Full territorial scope of the Autonomous Community of Andalusia, of 87,268 km2 extension and a distance of 502 km between the most distant universities (UAL-UHU). M. Romero-Gutierrez et al. / Evaluation and Program Planning 54 (2016) 41–49 44 Table 2 Answered samples. University UAL UCA UCO UMA UGR UPO Total Participants (% per university) 2 10 (90.9) 3 6 (40) 2 6 (50) 1 6 (54.5) 2 11 (84.6) 0 5 (41.6) Teachers: 10 (100%) Students: 44 (59.4%) curriculum; relationship between university students, teachers, or both; faculties’ and students’ motivation; technology innovation; etc. In order to respect the answers from the open questions of the participants and to be true to their content, the answers analysis involved using an open coding so that the responses were grouped by similarity, and emerging categories were later established. The authors involved in this research have conducted independently a detailed analysis of each response, finding a high degree of consensus among the researchers greater than 83%. 3.3. Data analysis developed The data collected from the open questions were subjected to content analysis (Patton, 1987, 1990; Ponce Morales & Tójar Hurtado, 2014; Perales-Palacios et al., 2014). The codes that emerged in the content analysis constituted the themes discussed in the results section of this paper. Firstly, in order to deeply understand the content of the contributions made by the participants in relation to their perception about what really runs on the EE joint master’s (research question 1), we will present the results of the qualitative analysis conducted, focusing on the aspects that are most significant and representative of the satisfaction-dissatisfaction. In this case, we gather the qualitative answers of the participants by similarity, without preset issues, and we show those answers according to the general SWOT of the master’s, extending it through the most recurrent themes (Section 4.1). Furthermore, this analysis helps us to highlight the factors or situations that may affect the organisation in a positive or negative way (research question 2). Secondly (Section 4.2), we show an original graphic representation based on Microsoft Excel’s radial graphs of the number of answers per category in each university. This representation helps compare the aspects that students highlighted in some universities, allowing conclusions about the agreements and disagreements and particularities of each university (research question 4). 4. Results and data analysis 4.1. General SWOT results: emerging issues of students’ perceptions about the EE joint master’s degree programme The 452 answers given by the 44 surveys from different universities (Table 2). Respondents have been classified by similarity in 36 emerging issues. These issues provide an overall view of the most significant aspects of the master’s considered by the students. As each category contains a different number of answers, we show the most frequent (up to five answers per category) ones organised in the general SWOT (Table 3). The overall comparison between positive and negative answers (frequency, Table 2) indicates a balance in the students’ perceptions about the weight of aspects that make them feel satisfied (W + T = 223) and dissatisfied (S + O = 229). If we pay attention to the different kinds of positive and negative responses (Table 2), while the proportion of strengths/opportunities is evenly split (125 and 104 inputs, respectively), the number of weaknesses is quite higher than the number of threats proposed (136 and 87 inputs, respectively). In order to simplify its view and compare frequency per university (Section 4.2), we have represented these SWOT responses in Chart 1. Most frequent items, using different symbols for each SWOT section (Chart 1); strengths (S) as a triangle, weaknesses (W) as a diamond, opportunities (O) as a round and finally, threats (T) as an square. At first glance, it appears that S, W, and O frequencies are more distant from the centre of the graph, while those of T are very close to the centre. This, the highest number of responses internal analysis (S + W = 261) than the external (T + O = 191), indicates that students perceive more easily the issues that directly depend on the organisation of the master’s degree than those beyond their control. This representation of the general SWOT (Table 3) serves to quickly display those aspects most identified by students as strengths (‘‘motivation’’3 and ‘‘interuniversity nature’’) and as main weaknesses ‘‘coordination’’ and lesser extent ‘‘content’’, but also to consider the ‘‘technological innovation’’ and ‘‘economic situation’’ as weaknesses of the master’s degree development. To detail the information shown in Table 3, in the following sections we show and analyse the concrete answers referred to the items ‘‘technological innovation’’ (Section 4.2.1) and ‘‘motivation’’ (Section 4.2.2), since these items are the most common in each of the four sections of the SWOT. Furthermore, the ‘‘inter-university nature’’ is highlighted in the two positive sections (S and O); therefore, it also deserves our attention (Section 4.3). The analysis will be extended to issues with higher frequency in only one section of the SWOT, distinguishing by university: ‘‘coordination’’, ‘‘contents’’, ‘‘professional perspective’’, and ‘‘economic situation’’ (Section 4.4). 4.2. Items present in all the sections of the SWOT 4.2.1. Technological innovation In order to illustrate how the answers from one category (‘‘technological innovation’’) appear in each section of the SWOT, examples of some answers from students are shown in Table 4. The high frequency of answers grouped in this category in every SWOT section underline the importance that the students grant to important aspects in the design and implementation of the master’s degree. These issues, referring mainly to technical aspects, are strongly related to the possibility of developing the lessons simultaneously, and therefore are directly related to the fact that the master’s degree was developed online/on site. The frequencies in Table 4 (in brackets) show that ‘‘technological innovation’’ is perceived as a more negative (18 + 7) than positive (13 + 8) aspect. Responses seem to indicate implicitly that students perceive a loss of essential aspects of onsite teaching related to the proximity to the teacher. For instance: distance between the teacher and the students to see our faces (weaknesses); easy distractions in class or making the education impersonal (threats). 3 Henceforth, we reserve the italics for students’ direct quotes and we put in quotes each category. M. Romero-Gutierrez et al. / Evaluation and Program Planning 54 (2016) 41–49 Table 3 SWOT overall view of the most frequent categories. Weaknesses (frequency 136) Threats (frequency 87) ‘‘coordination’’a (33) contents (23) tech. Innovation (18) motivation (12) economic Situation (13) motivation (9) administration (7) Strengths (frequency 125) motivation (37) inter-university (32) tech. Innovation (13) Frequencies Weaknesses + Strengths = 136 + 125 = 261 45 Table 4 SWOT of the ‘‘technological innovation’’ category. W + T = 223 tech. Innovation (7) Opportunities (frequency 104) + professional perspective (26) inter-university (14) contents (8) motivation (8) tech. Innovation (8) S + O = 229 Frequencies Threats + Opportunities = 87 + 104 = 191 a Others categories with low frequencies are: attendance, competition, consolidation, contacts, degree, students’ assessment, faculty’s number, Faculty’s training, hard work, internships, interrelationships, legal framework, master’s expansion, pedagogical methodology, ratio of students/teachers, objectives, participation, professional intrusion, reality, requirements, research, seminars, social/legal recognition, special sessions, thesis, timetable, values. 4.2.2. Motivation Some of the responses from the students related to the category ‘‘motivation’’ are shown below (Table 5). This category is considered as a major point of the student perceptions about the master’s degree development, with more positive aspects (37 + 8) than negatives (12 + 9). Positive answers refer to the good feelings and atmosphere generated among the students from the same university: the classmates and the enjoyable evenings spent together (UPO); it is a group . . . with funny and sociable people (UCO); the friendships in the UGR group let us work better as a team, each one contributes with different things, which enriches us more as a team (UGR); or in general: creativity, dynamism, and positivity (UCO); good group cohesion (UPO). Similarly, the excitement expressed by the students in their answers is remarkable: we are people worried about the time we are living in and we want to change the world; and we will not Weaknesses (18) Threats (7) Technical problems of configuration and ICT’s training Distance from the teacher Depersonalised learning Strengths (13) Opportunities (8) Facilities to carry out the master’s, because you can access classes from home or see the sessions afterwards Convenience to follow lessons Communication tools (Platform) resign ourselves to things the world wants to impose (UAL); empowerment of the students and faculties (we believe it) (UPO); inspiration of the faculty and students for the master’s theme (UGR); the interpersonal relationship between students and teachers: we can have a friendly relationship with the teachers (UAL). On the other hand, negative answers only refer to the lack of interest without indicating the causes, except two of the remarkable answers in Table 5 that refer to the (technical) failures or the lack of feedback after presenting papers and activities results. 4.3. Category present only in the positive sections of the SWOT: interuniversity nature This category appears as very frequent in the positive aspects of SWOT (Table 3), which shows that students perceive this feature as one of the centrepieces of this EE joint master’s degree, as it is not considered as a weakness or threat. Their answers show their suitable decision with the access to the master degree: This master’s is the envy of the whole university because it is interuniversity and due to the use of new technologies (UAL); from several Andalusian provinces (UMA); (to be able to) mix cultures or the variety of zones (UCO). Among the opportunities, the students underline: meeting people and being able to interact with them from end-to-end in Andalucı́a (UAL); the professional opportunity that the master’s degree implies, being the only one with the possibility of making contact with teachers and students from different Andalusian universities, which makes it very interesting for the students and for the curriculum vitae (UMA); Andalusian master’s degree (UPO); Table 5 SWOT of the ‘‘motivation’’ category. Chart 1. General SWOT of the most frequent categories. Weaknesses (12) Threats (9) Lack of motivation Not much motivation in some subjects, because we do the activities but we do not receive any feedback from the teachers in all the courses Increasing discouragement due to the reiterated problems in the master’s Loss of interest Apparent interest Strengths (37) Opportunities (8) Faculties and students motivated by the subject Aims and attitudes shared by a lot of participants We are a group willing to take on the world. We have eagerness and will to work as teachers Institutional and business interest for the environmental image and education Vocation and attitude for a necessary degree in the actual world 46 M. Romero-Gutierrez et al. / Evaluation and Program Planning 54 (2016) 41–49 it is a pioneer initiative in Environmental Education in Andalucı́a (UGR); meeting different environmental realities through the classmates since it is a joint master’s degree (UCO). 4.4. Most recurrent items in one section of the SWOT distinguishing by university 4.4.1. Coordination (weak point) This category is noted exclusively as a frequent weakness (23 answers). The answers from the students indicate two main weaknesses: On one hand, the students emphasise the lack of coordination among faculties for the same subject: the lack of connection among contents in the same subject (UPO); lack of organisation in some subjects, because the contents are repeated in different subjects, making the class boring (UCO). And, on the other hand, the participants mention the lack of coordination among faculties from different universities: lack of foresight in the calendar when there are broadcasts from universities with local holidays (UPO), or the lack of information to the students when the itineraries were divided and the feeling of chaos (UPO). 4.4.2. Contents (weak point) This category is marked as a frequent weakness (23 answers) and related to the demand of a specific kind of contents (pedagogical or environmental contents) to be considered in the master’s degree design. They identify a lack of participants whose background had included environmental science training: too much didactics and a lack of scientific contents (UAL); lack of people specialised in environmental science this year which does not produce knowledge from classmates (UCO); I think that students who come from teacher Training Degrees should give more content of environmental knowledge to the students from environmental sciences Degrees and vice versa (UCO). Although, sometimes the student demand is more related to the teachers’ qualification: contents are not adapted to non-formal academic circles (UPO); the role of environmental educators in the business and social world (UPO). 4.4.3. ‘‘Economic situation’’ and ‘‘professional perspective’’ (threat and opportunity) The main threats identified by 13 students are the economic situation due to the labour instability that is related to (UAL), budget cuts (UGR), increase in university taxes (UCA), and crisis (UMA). Nevertheless, isolated answers which reflect a perception of the current economic situation as an opportunity have been also given: crisis might work as an opportunity to change (UCA); the current worldwide economic situation needs appropriate responses (UMA). In that respect, the most frequent opportunity (26 answers) is the ‘‘professional perspective’’ due to what an official master’s degree creation represents: giving the rank of official master to the environmental education field (UAL); recognition by the community (UAL). And the job opportunities that the master’s degree offers: after completing the master’s degree you are able to choose among different work paths: setting up your own business, working in city councils, organisations. . .(UCO); the opportunity of getting a decent and recognised job (UAL); possibility of self-employment in different countries and scenarios (UCO). 4.5. Frequencies of items in each university In order to answer research question 4, we compare the students’ responses differentiated according to their university through a more detailed representation (Charts 2–7).4 4 Frequencies = 1 has been eliminated to avoid congestion in the charts. The frequencies of answers by issues are shown in Charts 2– 7. On the centre of the chart means an equal frequency to one, and those issues with high frequencies are located far from the centre. The number of radii changes from one chart to another in function of the issues that appear in each university. Thus, this particular representation of the data shows the SWOT results in each university in a clear and visual manner, which helps us to compare the general SWOT between each university. The UCA chart shape (#3, top right) is close to the general SWOT (Chart 1) by the similar number of radios: the lack of coordination, the absence of feedback in the evaluation, the technical bugs and crashes, or the threats related to governess economic cuts in master’s funding (‘‘administration’’) that produce a remarkable lack of motivation, in the students’ words. All these negative answers do not compensate for the agreement of the main positive responses (‘‘inter-university nature’’ and students’ and teachers’ motivation highlighted by students), which explains the huge lack of satisfaction shown in Table 3. Students from the UAL (in Chart 2, top left) answered similar number of positive and negative responses (50 positive, 48 negative, Romero-Gutierrez et al., 2015). This equilibrium is transformed into a wide dispersion at high frequencies: agreeing with the main SWOT (Table 3) in the strengths issues: ‘‘interuniversity’’, ‘‘motivation’’, ‘‘technological innovation’’ and showing new weaknesses related to curricular aspects: ‘‘contents’’, ‘‘methodology’’, ‘‘objectives’’. The external analysis of the UAL-SWOT coincides with the general SWOT (Table 3) because it remarks as an opportunity the ‘‘professional perspectives’’, the recognition of an ‘‘official degree’’ and the ‘‘economic situation’’ as a main threat. The high satisfaction shown by the students in the UCO (36 positive and 30 negative answers, Romero-Gutierrez et al., 2015) seems due to the number of student answers related to the ‘‘inter-university nature’’ and the ‘‘technologic innovation’’ as strengths (Chart 4), as in general SWOT. This positive perception among the students is also due to the ‘‘professional opportunities’’ that the realisation of the master’s degree entails. Negative aspects are found less frequently than the positives and are more dispersed (Chart 4), between the ‘‘coordination’’ and the ‘‘contents’’ as weaknesses, or the ‘‘requirements’’ as threats. In this university, there are issues different from the general SWOT: the control of ‘‘attendance’’ as a weakness and the ‘‘faculty training’’ of the master’s as a strength. In the UGR (Chart 5), in addition to ‘‘coordination’’, it should be pointed out the important weight of the technological failures (‘‘technological innovation’’) when the weaknesses of the master’s are considered. The ‘‘economic situation’’ and the ‘‘professional intrusion’’ (new category) are shown as the main threats balanced with professional opportunities, the ‘‘inter-university nature’’ and the ‘‘contents’’ of the master’s. As can be seen in this university, as in the UCA, the agreement among the most frequent issues is remarkable. The great number of issues of the UMA’s SWOT representation (Chart 6) is due to the diversity of answers in the external analysis, especially those referring to opportunities. The remaining elements seem to be more agreeable, showing some resemblance to the general SWOT (Table 3) in respect to the weaknesses (‘‘coordination’’ and ‘‘contents’’) and the strengths (‘‘motivation’’ or ‘‘technological motivation’’). New issues appear as opportunities not marked as frequent, either in the general SWOT or other universities, such as ‘‘internships’’, the ‘‘inter-university seminars’’, ‘‘values’’, and ‘‘motivation’’ (the most frequent opportunity). In the UPO (Chart 7) the ‘‘motivation’’ and the ‘‘inter-university nature’’ issues are the main strengths and showed a lack of satisfaction between positive (34) and negative (42) answers in its SWOT. It seems to come from the ‘‘coordination’’ (considered as a weakness by all the students from this university) and some curricular aspects as the ‘‘contents’’ or the ‘‘methodology’’. This M. Romero-Gutierrez et al. / Evaluation and Program Planning 54 (2016) 41–49 47 Charts 2–7. SWOT of the most frequent categories by Universities university (UPO) also differs in the threats analysis with the general SWOT (Table 3), because while the ‘‘professional intrusion’’ has already appeared in another university (UGR), here it is remarked the fact that the degree is not recognised by the contracting parties, as the possible lack of motivation highlighted by the technological bugs or crashes (‘‘technological innovation’’). 5. Discussion and conclusions The significance of improving the Environmental Education effectiveness leads us to focus our study on the evaluation of an EE master’s degree. A SWOT analysis is one tool to use in a strategic planning process (Balamuralikrishna & Dugger, 1995; Orr, 2013), 48 M. Romero-Gutierrez et al. / Evaluation and Program Planning 54 (2016) 41–49 where strengths and weaknesses are revealed to identify important issues, useful to lay the foundations for a more complete evaluation. Specifically, in this paper, the answers from the SWOT analysis of the students’ perceptions about an EE joint master’s degree give us some clues to design a Likert scale questionnaire that will let specify weights to each issue by the participants. In addition to the results that emerge from the analysis, we offer an assessment tool and a proposal for data processing that can be exportable to other evaluation of educational programmes, which is a relevant contribution considering the limited range of specific and transferable assessment proposals that permit the analysis of the inner and outer aspects by using the participants’ opinions (Darling-Hammond, 2000). The SWOT provides a focused measure on how the students perceive the programme (Orr, 2013). The implemented online SWOT open-ended questionnaire questions offer the participants the opportunity to express their perceptions and opinions on the programme’s master’s degree under consideration, allowing appearing spontaneous reflections and values. Due to the qualitative nature of the answers offered in this study, we have carried out an emerging categorisation for similarity that, when it is quantified and represented graphically, gives us more useful information than the already predetermined aspects from the typical surveys about the teaching obligations, planning, patterns of teaching acts, or the assessment systems used. The treatment of the data developed has allowed for the comparison of students’ perceptions per universities of the evaluated master’s degree. The most remarkable aspects in the general SWOT as ‘‘negative’’ have been the ‘‘contents’’ (UAL, UCO, UMA, UPO), the ‘‘methodology’’ (UAL, UMA, UPO), and the ‘‘evaluation’’ (UCA), even though they also have been considered in two universities (UGR and UPO) as opportunities (research question 4). The emergent issues from the students’ answers in the SWOT provide information thanks to the implementation of an online questionnaire with open-questions. The most frequent issues help us identify the main characteristics of the master’s degree that work correctly as perceived by students (research question 1): - The ‘‘inter-university nature’’ is the main strong point because it has been remarked on in almost every university (except UGR and UMA) despite the failures in coordination mentioned by everyone. - The ‘‘technological innovation’’ has clear followers (UAL), detractors (UCA, UGR, and UPO), and a university that recognises its opportunities but at times recognises its failures (UCO). Moreover, this category usually appears related to other, for example, participants refer to the lack (or plenty) of ‘‘motivation’’, in most cases they usually include negative aspects related to technical failures. - The ‘‘professional perspectives’’ considered as an opportunity and the ‘‘economic situation’’ as a threat. It shows much agreement in almost all universities, although in some the threat of the ‘‘professional intrusion’’ is also remarked upon. - Last, but not least, is the relevance to all the universities and in all sections of the SWOT of the ‘‘motivation’’ as a strong point (UAL, UCO, UGR, UMA) that is balanced with the lack of motivation in some universities (UCA, UPO). In order to answer research question 2 (factors or situations that may affect the organisation), the technical problems occurring in the master’s (connection, audio bugs, crashes, etc.) seem to have more weight than the remarkable strengths for students, such as the convenience of having recorded lessons or the possibility to attend classes at home or anywhere online, or even opportunities where the advantage of using the tools of online communication is recognised. Related to the prospective improvement in planning programme (research question 3), issues with higher frequency in each-one section of the SWOT distinguishing by university are the ‘‘coordination’’ and ‘‘contents’’ (weak points), and the ‘‘economic situation’’ and ‘‘professional perspective’’ (threat and opportunity, respectively): - The students emphasise the lack of coordination among faculties for the same subject and among faculties from different universities. This seems to show the disjointed nature of the subjects and the need to search for inner coherence in each subject. - The inputs related to the ‘‘contents’’ represent valued information for the improvement of the master’s degree development. Concretely, taking into account the students’ backgrounds (mostly from degrees related to education and a few others from environmental science), students demand to emphasise the teaching of environmental science contents instead of the intense pedagogical training they receive. The current ‘‘economic situation’’ with consequent higher fees at the universities and the uncertain ‘‘professional perspective’’ given the volatile job situation are issues that concern the students, although, the students also perceive as opportunity the different job options the master’s degree promotes. Furthermore, the description of the master’s degree according to the emerging issues may provide valuable material for continued planning and support-generating activities. A comparison among the different universities has allowed us to describe the specific perception manifested in each one. While the strengths can be presented and emphasised for potential improvements, a discussion of weaknesses and threats can provide useful information for strengthening the planning where possible, or anticipating the effects of possible threats. For example, at UCA, UGR, and UPO (Charts 3, 5 and 7), we can extract from the participants’ answers that the failures of the coordination in some subjects, the technological crashes, and the lack of feedback on assessment, reduce the high students motivation. Nor do the satisfaction for the ‘‘inter-university nature’’ or professionalism of the master’s degree. These three universities present fewer issues with higher frequencies in the answers, which indicate a general agreement between universities on these aspects. On the contrary, UAL, UCO, and UMA show a high diversity in the topics, which indicates that there are no coincidences among the student participants over the outstanding failures or the strengths, except in the case of the ‘‘inter-university nature’’ (UAL and UCO) and the ‘‘motivation’’ (UMA). The challenges and opportunities outlined above are not unique to the field of environmental programme evaluation. However, the increasing complexity of many issues facing environmental conditions lends a special urgency focused on the improvement of environmental educators’ training. Therefore, based on the analysed data, we may conclude that SWOT and the treatment of the results described offer a good opportunity to evaluate the application of the EE programme, because it allows for the description of the major and minor points in the development of the master’s degree that can result in high utility for the elaboration of planning improvements. The results obtained in this paper show a ‘‘snap shot’’ of the master’s degree performance. In future research, in order to avoid this evaluation by a photo finish, these results will be compared with analysis of the lessons development from online records. This will allow a more detailed and dynamic analysis of the significant issues that led to such responses from the students of this master’s degree edition. Finally, such as an agenda for future work, as we mentioned before, some challenges rise from this paper: situations that M. Romero-Gutierrez et al. / Evaluation and Program Planning 54 (2016) 41–49 influenced the organisation could be tested through the comparison of students and teachers’ perceptions and the failures in relation to ‘‘contents’’, could also be researched by analysing the lessons video-recorded as a strategic master’s degree plan (RomeroGutierrez et al., 2015). Acknowledgements The authors acknowledge Junta de Andalucia (Regional government from South of Spain) which funded the SENSOCIENCIA Project (P-11-SEJ-7385). Also thanks to participants on EE Master Degree for their collaboration to answer the open-questionnaire. References Aivazidis, C., Lazaridou, M., & Hellden, G. F. (2006). A comparison between a traditional and an online environmental educational program. The Journal of Environmental Education, 37(4), 45–54. Aypay, A. (2009). Teachers’ evaluation of their pre-service teacher training. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 9(3), 1113–1123. Aznar Minguet, P., Martinez-Agut, M. P., Palacios, B., Piñero, A., & Ull, M. A. (2011). Introducing sustainability into university curricula: An indicator and baseline survey of the views of university teachers at the University of Valencia. Environmental Education Research, 17(2), 145–166. Balamuralikrishna, R., & Dugger, J. C. (1995). SWOT analysis: A management tool for initiating new programs in vocational schools. Journal of Vocational and Technical Education, 12(1), 1–6. Bowe, A. G. (2015). The development of education indicators for measuring quality in the English-speaking Caribbean: How far have we come? Evaluation and Program Planning, 48, 31–46. Da Costa, A. F., Pegado, E., Ávila, P., & Coelho, A. R. (2013). Mixed-methods evaluation in complex programmes: The national reading plan in Portugal. Evaluation and Program Planning, 39, 1–9. Carleton-Hug, A., & Hug, J. W. (2010). Challenges and opportunities for evaluating environmental education programs. Evaluation and Program Planning, 33(2), 159–164. Danca, A. C. (2006). SWOT analysis. Retrieved from http://www.stfrancis.edu/ content/ba/ghkickul/stuwebs/btopics/works/swot.htm Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). Reforming teacher preparation and licensing: Debating the evidence. Teachers College Record, 102(1), 28–56. Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Constructing 21st-century teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 5(3), 300–314. Duvall, J., & Zint, M. T. (2007). A review of research on the effectiveness of environmental education in promoting intergenerational learning. The Journal of Environmental Education, 38(4), 14–25. Engels, C. A., & Jacobson, S. K. (2007). Evaluating long-term effects of the Golden Lion Tamarin environmental education program in Brazil. The Journal of Environmental Education, 38(3), 3–14. Erdogan, M., & Tuncer, G. (2009). Evaluation of a course: ‘‘Education and awareness for sustainability’’. International Journal of Environmental & Science Education, 4(2), 133–146. Ernst, J., & Theimer, S. (2011). Evaluating the effects of environmental education programming on connectedness to nature. Environmental Education Research, 17(5), 577–598. Ghemawat, P. (2002). How business strategy tamed the ‘‘invisible hand’’. Retrieved from http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/3019.html Goldman, D., Yavetz, B., & Pe’er, S. (2006). Environmental literacy in teacher training in Israel: Environmental behavior of new students. The Journal of Environmental Education, 38(1), 3–22. Gorski, S. E. (1991). The SWOT team approach: Focusing on minorities. Community, Technical, and Junior College Journal, 61(3), 30–33. Gutiérrez-Pérez, J., Ojeda-Barceló, F., & Perales-Palacios, J. (2014). Sustainability culture and communication technologies – Possibilities for environmental educators. The International Journal of Sustainability Education, 9(1). Hurlimann, A. C. (2009). Responding to environmental challenges: An initial assessment of higher education curricula needs by Australian planning professionals. Environmental Education Research, 15(6), 643–659. Jain, S., & Pant, P. (2010). An environmental management system for educational institute: A case study of TERI University, New Delhi. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 11(3), 236–249. Jeronen, E., Jeronen, J., & Raustia, H. (2009). Environmental education in Finland: A case study of environmental education in nature schools. International Journal of Environmental & Science Education, 4(1), 1–23. 49 Jeronen, E., & Kaikkonen, M. (2002). Thoughts of children and adults about the environment and environmental education. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 11(4), 341–353. Lisowski, M. (2006). Using a logic model to review and analyze an environmental education program. The Journal of Environmental Education, 37(4), 58–59. McNamara, C. (2008–2014). Basic guide to program evaluation. Free Management Library (4 March). Retrieved from http://managementhelp.org/evaluation/ programevaluation-guide.htm Negev, M., Sagy, G., & Garb, Y. (2008). Evaluating the environmental literacy of Israeli elementary and high school students. The Journal of Environmental Education, 39(2), 3–20. Orr, B. (2013). Conducting a SWOT analysis for program improvement. US-China Education Review A, 3(6), 381–384. Overholt, E., & MacKenzie, A. H. (2005). Long-term stream monitoring programs in US secondary schools. The Journal of Environmental Education, 36(3), 51–56. Patton, M. Q. (1987). How to use qualitative methods in evaluation. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (second ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Patton, M. Q. (2008). Utilization-focused evaluation (fourth ed., p. 688). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. Perales-Palacios, F. J., Burgos-Peredo, Ó., & Gutiérrez-Pérez, J. (2014). The EcoSchools program. A critical evaluation of strengths and weaknesses. Perfiles Educativos, 36(145), 21–39. Ponce Morales, I., & Tójar Hurtado, J. C. (2014). Análisis de competencias y oportunidades de empleo en una enseñanza de posgrado. Propuesta metodológica de evaluación en un máster interuniversitario de educación ambiental. Profesorado. Revista de Currı́culum Y Formación Del Profesorado, 18(2), 171–187. Powell, R. B., Stern, M. J., & Ardoin, N. (2006). A sustainable evaluation framework and its application. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 5(4), 231–241. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15330150601059290 Powers, A. L. (2004). An evaluation of four place-based education programs. The Journal of Environmental Education, 35(4), 17–32. Rivera, M. A. J., Manning, M. M., & Krupp, D. A. (2013). A unique marine and environmental science program for high school teachers in Hawai‘i: Professional development, teacher confidence, and lessons learned. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 8(2), 217–239. Romero-Gutierrez, M., Martinez-Chico, M., & Jimenez-Liso, M. R. (2015). Evaluación del máster interuniversitario de educación ambiental a través de las percepciones de estudiantes y profesores en un análisis DAFO. Revista Eureka Sobre Enseñanza y Divulgación de las Ciencias, 12(2), 347–361. Ruiz-Mayen, I., Barraza, L., Bodenhorn, B., & Reyes-Garcia, V. (2009). Evaluating the impact of an environmental education programme: An empirical study in Mexico. Environmental Education Research, 15(3), 371–387. Smith-Sebasto, N. J. (2006). Preparing effective environmental educators. The Journal of Environmental Education, 38(1), 60–62. Smith-Sebasto, N. J., & Semrau, H. J. (2004). Evaluation of the environmental education program at the New Jersey School of Conservation. The Journal of Environmental Education, 36(1), 3–18. Stern, M. J., Powell, R. B., & Hill, D. (2014). Environmental education program evaluation in the new millennium: What do we measure and what have we learned? Environmental Education Research, 20(5), 581–611. Tarrant, M., & Lyons, K. (2011). The effect of short-term educational travel programs on environmental citizenship. Environmental Education Research, 18(3), 403–416. Van Petegem, P., Blieck, A., & Boeve-De Pauw, J. (2007). Evaluating the implementation process of environmental education in preservice teacher education: Two case studies. The Journal of Environmental Education, 38(2), 47– 54. Wesselink, R., & Wals, A. E. J. (2011). Developing competence profiles for educators in environmental education organisations in the Netherlands. Environmental Education Research, 17(1), 69–90. Zint, M. T., Dowd, P. F., & Covitt, B. A. (2011). Enhancing environmental educators’ evaluation competencies: Insights from an examination of the effectiveness of the My Environmental Education Evaluation Resource Assistant (MEERA) website. Environmental Education Research, 17(4), 471–797. M. Rut Jimenez-Liso, Senior Lecturer of Science Education at the University of Almerı́a (Spain). Currently involved as a teacher in various degrees and master’s degrees related to Environmental Education and Training of science teachers. Her main research interests are related to the models and everyday chemistry and science teacher training. She also works on news and social scientific controversies jobs and educational applications and recently on assessment of educators programmes (http:// scholar.google.es/citations?hl=es&user=-2IUAm4AAAAJ). It belongs to the board of the Spanish Association of professors and researchers Teaching Experimental Sciences and a member of ESERA.