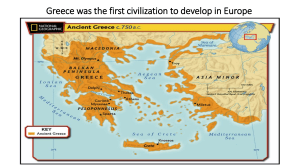

Ancient Greece Greek Mask, gold, Medusa Ancient Greece Scholars believe that Greek architects used a concept, known as the Golden Section, to design and construct buildings such as the Parthenon. The Golden Section is a mathematical process in which shapes grow larger according to a fixed ratio as they rotate around a central axis. Greek architects used the Golden Section to determine the proportions of building elements such as columns. Why do historians place so much importance on events that happened more than 30 centuries ago in an area not much larger than the state of Arizona? Why are the names of such artists as Myron, Phidias, and Polyclitus still held in esteem, even though none of their works is known for certain to exist today? Why are plays by Sophocles still performed all over the world? Why do people still find the comedy of Aristophanes funny after thousands of years? The answer is simple: That area – Greece - was the birthplace of Western civilization. Furthermore, its contributions to art, literature, and theatre, have had a profound effect on artists up to the present day. Vocabulary Raking cornice Stylobate Ionic order Cornice Pediment Corinthian order Frieze Entablature Lintel Column Capital Colonnade Shaft Doric order Silver decadrachm (coin) 375 B.C. The history of ancient Greece begins around 2000 B.C. At that time the earliest people probably entered the land. The descendants of these primitive peoples remained there, and in about 500 years a strong culture known as the Mycenaean had formed. However, the power of the Mycenaeans eventually gave way to that of a stronger people. After a series of invasions, the warlike Dorians took over the land in about 1100 B.C. This event changed the way of life in many areas as the conquerors mingled with the native populations. Towns eventually grew into small, independent city-states. Unlike many other civilizations, which developed as collections of city-states that formed kingdoms or empires, the Greek city-states remained fiercely independent. The independence of Greek city-states can be accounted for, at least in part, by geography. Greece is divided by mountains, valleys, and the sea. (See map) These physical separations made communication difficult. In addition to these natural barriers, social barriers of local pride and jealousy also divided the city-states. These factors combined to keep the Greek city-states from uniting to form a nation. History of Greek City-States There was continuing rivalry among the city-states, but none ever succeeded in conquering the others. The rivalry was so intense that the city-states could not even agree to work together toward common goals. Fear alone finally united them long enough to fight off invaders from Persia during the fifth century B.C. Suspecting further invasions by the Persians, several city-states joined together to form a defensive alliance. This alliance came to be known as the Delian League because its treasury was kept on the island of Delos. The larger cities contributed ships and men to this alliance, while the smaller cities gave money. Because it was the most powerful member of the Delian League, Athens was made its permanent head. Athenian representatives were put in charge of the fleet and were authorized to collect money for the treasury. Pericles, the Athenian leader, moved the treasury from Delos to Athens. Before long, Pericles began to use the Delian League's money to rebuild and beautify Athens, which had been badly damaged by the Persian invaders. The Peloponnesian War The greatness of Athens was not destined to last long. Pericles’ actions were bitterly resented by the other members of the Delian League, especially Saprta and Corinth. Finally, in 431 B.C., this resentment led to the Peloponnesian War. At first, Pericles successfully withstood the challenge of Sparta and the other city-states, but in 430 B.C. a terrible plague killed a third of the Athenian population. A year later, Pericles himself was a victim of this plague. With the death of its leader, Athens was doomed. After Athens was defeated, a century of conflict followed. One city-state, then another gained the upper hand. This conflict so weakened the city-states that they were helpless before foreign invaders. In 338 B.C., Greece was conquered by Macedonia. Despite a history of rivalry, wars, and invasions, the Greek people made many important contributions to art. Their accomplishments in architecture, particularly temple architecture, were among their most enduring legacies to Western civilization. Greek Architecture The Greeks considered their temples dwelling places for the gods, who looked and often acted like humans. The Greeks believed that the gods controlled the universe and the destiny of every person on Earth. The highest goal for the Greeks was doing what the gods wanted them to do. As a result, fortune tellers and omens, which helped people discover the will of the gods, were important parts of religious practice. Early Greek Temples The earliest Greek temples were made of wood or brick, and these have since disappeared. As the economy prospered with the growth of trade, stone was used. Limestone and finally marble became the favorite building materials. The basic design of Greek temples did not change over the centuries. Greek builders chose not to alter a design that served their needs and was also pleasing to the eye. Instead, they made small improvements on the basic design in order to achieve perfection. Proof that they realized this perfection is represented in temples such as the Parthenon. It was built as a house for Athena, the goddess of wisdom and guardian of the city named in her honor. The Parthenon, Acropolis, Athens, Greece c. 447 B.C. The 1Parthenon made use of the most familiar features of Greek architecture: post-and lintel construction; a sloping, or gabled roof; and a colonnade. Like all Greek buildings, the parts of the Parthenon were carefully planned to be balanced, harmonious, and beautiful. Greek Temple Construction Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon is a simple rectangular building placed on a three-step platform. The Parthenon consisted of two rooms The smaller held the treasury of the Delian League, and the larger housed a large gold and ivory statue of Athena. Few citizens were allowed to see this statue. Only priests and a few attendants were allowed inside the sacred temple. Religious ceremonies attended by the citizens were held outdoors in front of the buildings. Exterior Design of the Parthenon Because few people were allowed inside the temple, there was no need for windows or interior decorations. Instead, attention centered on making the outside of the building as attractive as possible. DETAILS OF GREEK TEMPLE CONSTRUCTION Raking cornice. The raking cornice is a sloping element that slants above the horizontal cornice. Cornice. A cornice is a horizontal element above the frieze. Raking Cornice Frieze. This is a decorative band running across the upper part of a wall. Lintel. The lintel is a crossbeam supported by columns. Capital. The top element of a column. Shaft. The shaft is the main weight-bearing portion of a column. Pediment Cornice Frieze Entablature Lintel Capital Stylobate. Find the stylobate at the top step of the three-step platform. Pediment. This is the triangular section framed by the cornice and the raking cornice. column Shaft Entablature. The entablature is the upper portion, consisting of the lintel, frieze, and cornice. Column. A column is an upright post used to bear weight. Colonnade. A colonnade is formed by a line of columns. Stylobate Three step platform It is hard to see with the naked eye, but there are few, if any, perfectly straight lines on the entire structure. The three-step platform and the entablature around the building look straight but actually bend upward in a gradual are, so that the center is slightly higher than the ends. This means that the entire floor and ceiling form a low dome that is slightly higher in the middle than at the edges. The columns also curve slightly outward near their centers. Like muscles, they seem to bulge a bit as they hold up the great weight of the roof. In addition, each column slants inward toward the center of the building. The columns were slanted in this way to prevent a feeling of top-heaviness and to add a sense of stability to the building. Use of Color The Greeks preferred bright colors to the cold whiteness of their marble buildings. For this reason, they painted large areas of most buildings. Blue, red, green, and yellow were often used, although some details were coated with a thin layer of gold. Exposure to the weather has removed almost all of the color from these painted surfaces. If you look closely at the more protected places of these ancient buildings, however, you still might find a few faint traces of paint. The Parthenon has been put to a variety of uses over its long history. It was a Christian church in the fifth century and a mosque in the 15th century. Its present ruined state is due to an explosion that took place in the 17th century. The ruins have now been restored as much as possible with the original remains. The Acropolis The Parthenon was only one of several buildings erected on the sacred hill, or Acropolis, of Athens. The Acropolis is a mass of rock that rises abruptly 500 feet above the city. Like a huge pedestal, it was crowned with a group of magnificent buildings that symbolized the glory of Athens. Covering less than 8 acres, the Acropolis was filled with temples, statues, and great flights of steps. On the western edge was a huge statue of Athena so tall that the tip of her gleaming spear served as a beacon to ships at sea. The statue was created by the legendary sculptor Phidias, and it was said to have been made from the bronze shields of the defeated Persians. Today, the crumbling but still impressive ruins of the Acropolis are a reminder of a great civilization. The Three Orders of Decorative Style Over the centuries, the Greeks developed three orders, or decorative styles. Examples of these orders can be seen in various structures that were built by ancient Greeks and still survive today. The Doric Order The Parthenon was built according to the earliest decorative style, the Doric Order. Doric Order Ionic Order Corinthian Order In the Doric order, the principal feature is a simple, heavy column without a base, topped by a broad, plain capital. The Ionic Order The Greeks later began using another order, the Ionic. This order employed columns that were thinner and taller than those of the Doric. In the Ionic order, columns had an elaborate base and a capital carved into double scrolls that looked like the horns of a ram. This was a more elegant order than the Doric, and for a time architects felt it was suitable only for small temples. Such a temple was the little shrine to Athena Nike built on the Acropolis between 427 and 424 B.C. The more they looked at the new Ionic order, the more the Greeks began to appreciate it. Soon they began using it on larger structures such as the Erechtheum a temple located directly opposite the Parthenon. This building was named after Erechtheus, a legendary king of Athens who was said to have been a foster son of Athena. An unusual feature of the Erechtheum is the smaller of two porches added to its sides. On the Porch of the Maidens, the roof is supported by six caryatids, or columns carved to look like female figures. The Corinthian Order The most elaborate order was the Corinthian, developed late in the fifth century B.C. In the Corinthian order, the capital is elongated and decorated with leaves. It was believed that this order was suggested by a wicker basket overgrown with large acanthus leaves found on the grave of a young Greek maiden. At first, Corinthian columns were used only on the inside of buildings. Later, they replaced Ionic columns on the outside. A monument to Lysicrates built in Athens about three hundred years before the birth of Christ is the first known use of this order on the outside of a building. The Corinthian columns surround a hollow cylinder that once supported a trophy won by Lysicrates in a choral contest. Grecian gold Diadem The Parthenon. The Parthenon is remarkable for the astonishing technical skill of its construction. No mortar was used anywhere in the building. The stones were cut so precisely that, when fitted together, they form a single smooth surface. The columns, which appear to be carved from single blocks of stone, are actually composed of sections called drums. These are joined together by square pegs in the center. These sections are fitted together so tightly that the cracks between them are scarcely visible. Greek Vase Decoration The earliest Greek vases were decorated with bands of simple geometric patterns covering most of the vessel. Eventually the entire vase was decorated in this way. The years between 900 and 700 B.C., when this form of decoration was being used, are called the Geometric period. Early in the eighth century B.C., artists began to add figures to the geometric designs on their vases. Some of the best of these figures were painted on large funeral vases. These vases were used in much the same way as tombstones are used today, as grave markers. The figures on these vases are made of triangles and lines, and look like simple stick figures. Several figures often appear on either side of a figure representing the deceased, as though they are paying their last respects. Their hands are raised, pulling on their hair in a gesture of grief and despair. Funerary Vase. Athens, Greece. c. Eighth century B.C. Terra cotta. Realism in Vase Decoration In time, vase figures became more lifelike and were placed in storytelling scenes. An excellent example of this kind of painting is provided by a vase showing two figures engrossed in a game (It was created by an artist named Exekias (ex-eekee-us) more than 2,500 years ago Exekias's vase shows two Greek generals playing a board game, probably one in which a roll of the dice determines the number of moves around the board. The names of the generals are written on the vase. They are two great heroes from Greek literature, Ajax and Achilles. The words being spoken by these warriors are shown coming from their mouths just as in a modern cartoon strip. Ajax has just said "tria," or "three," and Achilles is responding by saying "tessera," or "four." Legend says that these two great heroes were so involved in this game that their enemy was able to mount a surprise attack. Exekias shows the informality of this simple scene. The warriors' shields have been set aside, and Achilles, at the left, has casually pushed his war helmet back on his head. Ajax, forgetting briefly that they are at war, has removed his helmet and placed it out of the way on top of his shield. For a few moments, the Greek heroes are two ordinary people lost in friendly competition. Exekias. Vase with Ajax and Achilles Playing Morra (Dice). c. 540 B.o. Museo Gregoriano Etrusco, Vatican, Rome, Italy. Exekias's Use of Realism Exekias also has added details to make the scene as realistic as possible. An intricate design decorates the garments of the two generals. The facial features, hands, and feet are carefully drawn, although the eyes are shown from the front as they were in Egyptian art. Exekias was not so concerned with realism that he ignored good design, however. The scene is carefully arranged to complement the vase on which it was painted. The figures lean forward, and the curve of their backs repeats the curve of the vase. The lines of the spears continue the lines of the two handles and lead your eye to the board game, which is the center of interest in the composition. At this stage in Greek vase design, decorative patterns became a less important element, appearing near the rim or on the handles. Signed vases also began to appear for the first time in the early sixth century B.C., indicating that the potters and artists who made and decorated them were proud of their works and wished to be identified with them. Greek Painting. Although no great paintings from ancient Greece have survived, it is likely that Greek painters placed great importance on realism. The Roman historian Pliny the Elder supports this notion. He tells of a great competition that took place in the fifth century B.C. The purpose of this competition was to determine which of two famous painters was more skilled in producing lifelike works. The painters, Zeuxis and Parrhasius, faced each other with their works covered by curtains. Zeuxis confidently removed his curtain to reveal a painting of grapes so natural that birds were tricked into pecking at it. Certain that no one could outdo this feat, he asked Parrhasius to reveal his work. Parrhasius answered by inviting Zeuxis to remove the curtain from the painting. When Zeuxis tried, he found he could not - the curtain was the painting. Alexander the Great The Evolution of Greek Sculpture The buildings on the Acropolis were constructed during the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. This was a time in Greek history known as the Classical period. Like architecture, Greek sculpture also reached its peak during this period. To understand and appreciate Greek accomplishments in sculpture, it is necessary to look back to an even earlier time known as the Archaic period. Sculpture in the Archaic Period From around 600 to 480 B.C., Greek sculptors concentrated on carving large, freestanding figures known as Kouroi and Korai. Kouroi is the plural form of Kouros, meaning "youth," and Korai is the plural of Kore, or "maiden." The Kouros was a male youth who may have been a god or an athlete. This example is from the Archaic period. In some ways, the stiffness and the straight pose of this figure bring to mind Egyptian statues. The only suggestion of movement is in the left foot, which is placed slightly in front of the right foot. Even though the Kouros is stepping forward, both feet are flat on the ground. Of course, this is impossible unless the left leg is longer than the right. This problem could have been corrected if the right leg had been bent slightly, but it is perfectly straight. Later, Greek artists learned how to bend and twist their figures to make them appear more relaxed and natural. Except for the advancing left foot, the Kouros is symmetrically balanced. Details of hair, eyes, mouth, and chest are exactly alike on both sides of the figure, just as they are on Egyptian statues. Unlike Egyptian figures, the arms of the Kouros are separated slightly from the body and there is an open space between the legs. These openings help to break up the solid block of stone from which it was carved. No one knows for certain what the Kouros was meant to be. Some say he represents the sun god Apollo, whereas others insist that he is an athlete. The wide shoulders, long legs, flat stomach, and narrow hips may support the claim that he is an athlete. The face of the Kouros has a number of unusual features that were used over and over again in early Greek sculptures Among these are bulging eyes, a square chin, and a mouth with slightly upturned corners. This same mouth with its curious smile can be found in many early Greek sculptures. Greek sculptors wanted their figures to look more natural, and this smile may have been a first step toward greater realism. The Hera of Samos Komi were clothed women, often goddesses, that were also carved during the Archaic period. One of these goddesses, the Hem of Samos looks like a stone cylinder. It has the same stiff pose as the Kouros, but its right arm is held lightly against the body and the feet are placed tightly together. The missing left arm was bent and may once have held some symbol of authority. There is no deep carving here, and there are no open spaces. Instead, a surface pattern of lines suggests the garments and adds textural interest to the simple form. Sculpture in the Classical Period With each new generation, Greek artists became more bold and skillful. During the Classical period, they abandoned straight, stiff poses and made their figures appear to move in space. The discus thrower is about to put all his strength into a mighty throw, yet his face is completely calm and relaxed. In this respect, the figure is more idealistic than real. The athlete's throwing arm is frozen for a split second at the farthest point of the backswing. Details reveal that Myron had a thorough understanding of anatomy (how the body is structured). The athlete's right leg bears all his weight. His left leg is poised and ready to swing forward. Myron's chief material was bronze. As far as is known, he never worked in marble. Knowledge of his sculptures, however, comes from marble copies produced in Roman times. Not a single certified original work by Myron or any of the great sculptors of Greece exists today. Bronze works, which once numbered in the thousands, were melted down long ago. Even marble sculptures were mutilated, lost, or ruined by neglect. What is known of the ancient Greek works comes from copies made later by Romans, who used them to decorate their public buildings, villas, and gardens. Myron. Discobolus (Discus Thrower). Roman copy of a bronze original. 450 B.C. Sculptures for the Parthenon It is through Roman copies and descriptions by ancient writers that the works of Phidias (fhid-ee-us) are known. He was one of the greatest Greek sculptors and the creator of the gigantic statue of Athena in the Parthenon. Athena Parthenos Anyone who walked into the darkened room of the Parthenon would have faced Phidias's colossal goddess, towering to a height of 42 feet. Her skin was of the whitest ivory, and over 1 ton of gold was used to fashion her armor and garments. Precious stones were used for her eyes and as decorations for her helmet. A slight smile softened a face that looked as if it could turn cruel and angry at any moment. DISCUS. In Greece, the champion discus thrower was considered the greatest of athletes. In ancient times the disc was made of stone or metal. It is now made of wood with a smooth metal rim. OLYMPICS. The ancient Olympics were first held in 776 B.C. in Athens, to honor the god Zeus. In 1896, the first modem Olympics were held. Procession of Horsemen Every four years, the citizens of Athens held a great celebration in honor of Athena. The celebration included a procession in which people carried new garments and other offerings to Athena in the Parthenon. These gifts were given as thanks to the goddess for her divine protection. The procession was formed in the city below the Acropolis and moved slowly up a winding road through a huge gateway, the entrance to the sacred hill. Then it wound between temples dedicated to various gods and goddesses and past the huge bronze statue of Athena. The procession finally stopped at the entrance to the Parthenon where, during a solemn ceremony, the presentations were made. On a 525-foot band, or frieze, Greek sculptors, under the direction of Phidias, show how that parade looked more than 2,400 years ago. The frieze, which was over 3 feet high, ran around the top of the Parthenon walls like a giant stone storyboard. As they move, the figures bunch up in some places and spread out in others. At one point, an irritated horseman turns and raises his hand in warning to the horseman behind him, who has come up too quickly and jostled his mount. The rider behind responds by reining in his rearing horse. All along the parade, a strong sense of movement is evident in the spirited prancing of the horses and the lighthearted pace of the figures on foot. This pace seems to quicken as the procession draws closer to its destination. Perhaps movement is best suggested by the pattern of light and shadow in the carved drapery. This pattern of alternating light and dark values creates a flickering quality that becomes even more obvious when contrasted with the empty spaces between the figures. Another relief sculpture, this one from the Temple of Athena Nike, may remind you of Myron's discus thrower, since it also shows a figure frozen in action. The unknown sculptor has carved the goddess of victory as she bends down to fasten her sandal. A graceful movement is suggested by the thin drapery that clings to and defines the body of the goddess. The flowing folds of the drapery and the line of the shoulder and arms create a series of oval . lines that unifies the work. If you compare the handling of the drapery here with that of the Hera of Samos, you can appreciate more fully the great strides made by Greek sculptors over a 150-year period. Sculpture in the Hellenistic Period The Peloponnesian War left the Greek citystates weakened by conflict. To the north, Macedonia was ruled by Philip II, a military genius who had received a Greek education. Having unified his own country, Philip turned his attention to the Greek city-states. Their disunity was too great a temptation to resist; in 338 B.C. Philip defeated them and thus realized his dream of controlling the Greek world. The Spread of Greek Culture Before Philip could extend his empire further, he was assassinated while attending his daughter's wedding. His successor was his 20year-old son, Alexander the Great, who soon launched an amazing career of conquest. Alexander, whose teacher had been the famous Greek philosopher Aristotle, inherited his father's admiration for Greek culture. Alexander was determined to spread this culture throughout the world. As he marched with his army from one country to another, the Greek culture that he brought with him blended with other, non-Greek cultures. The period in which this occurred is known as the Hellenistic age. It lasted about two centuries, ending in 146 B.C .when Greece fell under Roman control. Expression in Hellenistic Sculpture Sculptors working during the Hellenistic period were extremely skillful and confident. They created dramatic and often violent images in bronze and marble. The sculptors were especially interested in faces, which were considered a mirror of inner emotions. Beauty was less important than emotional expression. Because of this new emphasis, many Hellenistic sculptures lack the precise balance and harmony of Classical sculptures. Burial Vessel The Dying Gaul Many of the features of the Hellenistic style can be observed in a life-size sculpture known as the Dying Gaul A Roman copy shows a figure that was once part of a large monument built to celebrate a victory over the Gauls, fierce warriors from the north. In this sculpture, you witness the final moments of a Gaul who was fatally wounded in battle. Blood flows freely from the wound in his side. The figure uses what little strength he has remaining to support himself with his right arm. He has difficulty supporting the weight of his head and it tilts downward. Pain and the knowledge that he is dying distort the features in his face. Expression of Emotion Works such as the Dying Gaul were intended to stir the emotions of the viewer. You are meant to become involved in this drama of a dying warrior, to share and feel his pain and loneliness and marvel at his quiet dignity at the moment of death. The Nike of Samothrace About 2,100 years ago, an unknown sculptor completed a larger-than-life marble work to celebrate a naval victory. The finished sculpture of a winged Nike (goddess of victory) stood on a pedestal that was made to look like the prow of a warship. She may have held a trumpet to her lips with her right hand while waving a banner with her left. A brisk ocean breeze whips Nike's garments into ripples and folds, adding to a feeling of forward movement. Her weight is supported by both legs, but the body twists in space, creating an overall sense of movement. It is not known for certain what great victory this sculpture was meant to celebrate. Also uncertain is its original location. The sculpture was found in 1875 on a lonely hillside of Samothrace, headless, without arms, and in 118 pieces. Pieced together, it is now known as the Nike of Samothrace and commonly called the Winged Victory. It stands proudly inside the main entrance to the Louvre, the great art museum in Paris. The Seated Boxer Ten years after the Nike of Samthrace was found, a bronze sculpture of a seated boxer was unearthed in Rome. It is not as dramatic as the Dying Gaul nor as spirited as the Winged Victory, but its emotional impact is undeniable. The unknown artist presents not a victorious young athlete but a mature, professional boxer, resting after a brutal match. Few details are spared in telling about the boxer's violent occupation. The swollen ears, scratches, and perspiration are signs of the punishment he has received. He turns his head to one side as he prepares to remove the leather boxing glove from his left hand. The near-profile view of his face reveals his broken nose and battered cheeks. There is no mistaking the joyless expression on his face, suggesting that he may have lost the match Stylistic Changes in Sculpture The development of Greek sculpture can be traced through an examination of the gods, goddesses, and athletes created from the Archaic period to the Hellenistic period. Sculptured figures produced during the Archaic period were solid and stiff. The Kouros, for example, was created at a time when artists were seeking greater control of their materials in order to make their statues look more real. By the Classical period, sculptors had achieved near perfection in balance, proportion, and sense of movement. The Discus Thrower demonstrates the sculptor's ability to create a realistic work. A later Classical work, the Spear Bearer, is an example of the balance, harmony, and beauty achieved by Greek sculptors. During Hellenistic times, sculptures such as the Seated Boxer reveal the artists' interest in more dramatic and emotional subjects. The Demand for Greek Artists The Romans defeated Macedonia and gave the Greek citystates their freedom as allies, but the troublesome Greeks caused Rome so much difficulty that their freedom was taken away and the city-state of Corinth burned. Athens alone continued to be held in respect and was allowed a certain amount of freedom. Although the great creative Hellenistic period had passed its peak, Greek artists were sought in other lands, where they spread the genius of their masters. Philip the Great, Ivory