Disruptive Classroom Behaviors: Post-Pandemic Research Proposal

advertisement

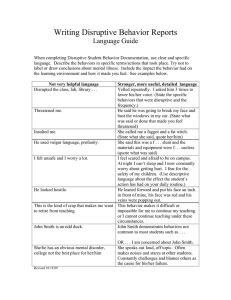

Basic Research Proposal Template NAME OF RESEARCHER/S LEAD PROPONENT MEMBER MEMBER IRENE M. DULAY RESEARCH TOPIC DISRUPTIVE CLASSROOM BEHAVIORS WORKING TITLE THE AFTERMATH: POST PANDEMIC-CLASSROOM BEHAVIOR-RELATED ISSUES AND THE NEW NORMAL RESPONSIVE APPROACH. Introduction & Rationale Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) emerged in December 2019 (Liu et al., 2020) and was declared a global public health emergency on March 11, 2020, by the World Health Organization (WHO) (Cucinotta & Vanelli, 2020). Since then, it has rapidly progressed into a pandemic. Unconstrained by borders, the virus spread quickly, prompting countries worldwide to adopt measures such as closing their borders, controlling entry and exit points, and disease tracking to curtail the disease outbreak. These measures not only have a high economic cost (Al-Awadhi et al., 2020; Laing, 2020) but also impose stress on public education systems. At this point in the pandemic, it's no secret that major disruptions to learning, like the ones we've seen over the last two and a half years, frequently result in challenging student behavior and setbacks in their social-emotional development. The Covid-19 pandemic impacts psychological conditions and changes in human behavior that cover broader aspects over a more extended period. It also changed the education system in all countries. As a result, teachers and students become familiar with distance learning interactions. These changes have an effect on student’s emotional well-being and performance. It has a real impact on everyday life and is one of the most influential aspects of the learning process. According to data released today by the National Center for Education Statistics, 87 percent of public schools reported that the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative impact on student socioemotional development during the 2021-22 school year (NCES). NCES is the United States' statistical office. The Institute of Education Sciences is a division of the Department of Education (IES). Similarly, 84% of public schools agreed or strongly agreed that students' behavioral development has been harmed. Respondents specifically attributed the COVID-19 pandemic and its lingering effects to an increase in incidents of classroom disruptions caused by student misconduct (56 percent), rowdiness outside of the classroom (49 percent), acts of disrespect towards teachers and staff (48 percent), and prohibited use of electronic devices (42 percent). Addressing students' social-emotional and behavioral needs at this stage of the pandemic will be a major undertaking. According to recent articles in Educational Leadership, disciplinary interventions like relational discipline or prevention interviews can be effective ways to build relationships and resolve potential conflicts in the classroom. But the new NCES data suggest that any strategies to promote positive behavioral and social-emotional development may need to be implemented, and maintained, with the support of additional training and staffing. Schools will also need to prioritize well-being for students and adults alike. On November 15, 2023, 97 public schools in the Philippines opened their doors once again to classroom instruction after 20 months of closure and a shift to remote learning for more than one full academic year. Schools had to apply to be a part of the pilot limited face-to-face and meet all the requirements set in the school safety assessment tool (SSAT), which includes alternative work arrangement, classroom layout and structure, school traffic management, protective measures, hygiene practices and safety procedures, communication strategy, including strategies for teaching and learning such as arrangements of class size and sections, class program with specific schedules, and teacher support. The guidelines also emphasize well-being and protection. As the COVID-19 pandemic starts to subside, the Department of Education has started to reopen its schools to students on August 22, 2022, following the guidelines stipulated under DepEd Order No. 34, s 2022. For many, this is a return to normality. In order to further strengthen the role of parents and teachers as the education frontline, the Department of Education (DepEd) has conducted a series of Psychosocial Support and Training for parents, teachers, and school heads and identified DepEd region and division non-teaching personnel. “As we enter a new school year, our learners in the secondary level are about to make another series of adjustments that might become stressful for them. This public health emergency has disrupted their lives as much as it severely impacted ours,” Director Ronilda Co of DepEd Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Services (DRRMS). The objective of the program is to prepare the teachers, identified DepEd non-teaching personnel, and parents in monitoring themselves, look after their wellness, and enable them to fulfill their respective duties and responsibilities in the education continuity. Teachers were equipped with skills on what strategies to use in executing classroom management once students are back in the classroom. Most of the studies on the pandemic focused on issues like teachers' opinions on distance education (Baran & Sadık, 2021; Han et al., 2021; Oducado, 2020), problems experienced in distance education (Kavuk & Demirtaş, 2021; Kultaş & Çalışkan, 2021; Saygı, 2021; Şahan & Parlar, 2021; Şenel Çoruhlu & Uzun, 2021), the effects of the pandemic on the education system (Bozkurt, 2020; Can; 2020a; Sarı & Nayır, 2020; Sezen-Gültekin & Algin, 2021), and virtual classroom management (Arslan & Şumuer, 2020; Can, 2020b; Hoang et al., 2021; Lathifah et al., 2020). However, with the transition to face-to-face education, the effects of the process in which schools were closed constitute the starting point of this research. The aim of this study is to reveal the effects of the disruption to face-to-face education after the pandemic restrictions on students’ behavior upon return to the classroom and the strategies being used by the teachers. Literature Review (need to add more and revise) DISRUPTIVE CLASSROOM BEHAVIOR Students young in school still have tender minds and cannot exactly identify what is right and wrong; thus, they need guidance and supervision from their teachers, guidance teachers, parents or guardians, and other stakeholders otherwise they can go in the wrong direction in life. Learning in school commands obedience to school rules and regulations as part of the student’s life, whereas discipline is also partly because it is paramount to learning (Thornberg, 2018). Teachers and the general public agree that a key issue in today's public schools is a lack of student discipline in the classroom. In today's classrooms, student discipline is still a major concern for most schools. More study is needed to eliminate disruptive behaviors among kids in order to provide the desired quality education for a brighter tomorrow and future productive citizens. Despite the numerous tactics that teachers have implanted from various training, we can clearly see disruptive behavior among pupils in this new generation. Disruptive behavior disorders are defined as “student behavior that systematically disrupts educational activities, undermines the habitual development of the tasks carried out in the classroom and causes the teacher to invest a significant amount of time in dealing with it, time that should otherwise be devoted to the processes of teaching and learning”. DBD’s definition based on DSM-5 is a repetitive and persistent pattern of behavior in which the basic rights of others or major age-appropriate societal norms or rules are violated, as manifested by the presence of criteria such as aggression to people or animals, and destruction of property. Disruptive behavior has different forms. One example is the student who talks continually while the teacher is teaching, interrupts the class by asking questions and making different sounds, uses different forbidden gadgets like cell phones in class, and becomes angry when the teacher opposes his/her inappropriate behavior. Early-onset DBD can have lifetime consequences, including school absences, poor school achievement, substance use, aggression, and anxiety; and DBD tends to continue to adulthood. Adolescents with DBD have low self-control, conflictual relationships, and low empathy. These students have difficulty with interpersonal relationships, and managing behavior, putting them at high risk for violence and substance abuse. A 2016 survey in Amsterdam revealed that the most prevalent disorders among adolescents were disruptive behaviors. Prevalence rates were 8.5% according to the DSMIV and 7.1% according to the ICD-10 in Brazilian youth in 2010. Most studies in this field are from western countries. For example, a 2012 Dutch population study indicated a mean prevalence rate of 12.8% for DBDs; with 9.3% for girls and 15.2% for boys. Although a 2016 community-based study on Iranian children and adolescents revealed the prevalence of psychiatric disorders was 10.55%, the study did not specifically screen for disruptive behavior and did not attend to gender differences in prevalence rates. In addition, this study did not include youth attending schools in non-capital cities, nor did it include important psychosocial factors that might be targeted for prevention, early detection, or treatment. Despite problems resulting from disruptive behavior, it has received little attention in the literature. Furthermore, compared to boys, the study of contributing factors of disruptive behavior in girls is underdeveloped. As such, it is important to identify possible predictors of disruptive behavior in both boys and girls in order to establish prevention and treatment programs. INTERVENTION PROGRAM It is expected that the findings would have profound importance to counseling and guidance work in the school context. Also, to capacitate teachers being the frontliners with different strategies in managing disruptive behaviors in the classroom. Even with the use of effective universal classroom management practices, some students will need additional behavioral support. However, to translate the implementation of new strategies into the classroom, professional development programs need to be adaptive to the complexities teachers face in providing instruction and managing classroom behaviors among diverse learners. Teachers also need support to successfully implement universal practices as well as to develop and enact plans for supporting students with disruptive behavior. This article describes a universal classroom management program that embeds coaching within the model. The coach supported teachers both in implementing universal strategies and in developing and implementing behavior support plans for students with disruptive behavior. The study evaluates the effectiveness of the behavior support plans and the types of coaching activities used to support these plans. Findings indicated that during meetings with teachers, coaches spent time action planning and providing performance feedback to teachers on their implementation of the behavior support plans. In addition, teachers reduced their rate of reprimands with the targeted at-risk students. Students receiving behavioral support demonstrated decreased rates of disruptive behavior, increased prosocial behavior, and a trend toward improved on-task behavior. In comparison, a matched sample of students with disruptive behaviors did not demonstrate improved outcomes. Implications for practice are discussed. Research findings revealed that appropriate behavior management techniques such as general praise; behavior-specific praise; and stating clear rules met the criteria of good strategies. These simple techniques can promote student classroom engagement and may decrease disruptive classroom behaviors (Gable, Hester, Rock, & Hughes, 2009; Henly, 2010; Kerr & Nelson, 2010; Wheeler & Richey, 2010; Pisacreta, Tincani, Connell, & Axelrod, 2011; Wan Mazwati Wan Yusoff, 2012). Besides these behavior management strategies, studies have shown that some evidencebased intervention programs were effective in reducing classroom disruptive behaviors. These intervention programs have been evaluated by researchers in a number of studies. Some examples of effective intervention programs are Good Behavior Game (Kellam et al., 2008; Kellam et al., 2011; Donaldson, Vollmer, Krous, Downs, & Berard, 2011); Fast Track Program (CPPRG, 1999; CPPRG, 2002); Raising Healthy Children (Brown, Catalano, Fleming, Haggerty, & Abbott, 2005; Hawkins, Kosterman, Catalano, Hill, & Abbott, 2005); and The Incredible Years program (Webster-Stratton & Hammond, 1997; Scott, Spender, Doolan, Jacobs, & Aspland, 2001; WebsterStratton et al., 2008). Besides applying behavior management techniques and intervention programs, the teacher can help reduce classroom disruptive behaviors by changing the physical and emotional environment in the classroom. A positive classroom emotional climate promotes healthy interactions, cooperation, and trust between teachers and students and students and students which may lead to lesser classroom misbehaviors (Brackett, Reyes, Rivers, Elbertson, & Salovey, 2011). Teachers who provide a structured, cooperative, and supportive learning environment; encourage and reinforce good effort by students; teach students social and emotional regulation skills; use effective instructional practices; and clearly conveyed what is expected from their students were proven to experience a reduction in student misbehaviors in their classroom (Walker, Ramsey, & Gresham, 2004; Conroy, Sutherland, Vo, Carrs, & Ogston, 2013). Another influential strategy to manage classroom misbehavior is to have a good personality and high social intelligence. Teachers with high social intelligence would create a supportive and positive classroom environment that enhances intrinsic motivation among students through discussion, recognition, involvement, and hinting (Yahyazadeh Jeloudar & Aida Suraya Md Yunus, 2011) In the Philippines, based on DECS Service Manual, 2000, Pursuant to Section I, Chapter III, Part IV of 2000 DECS Service Manual, every school shall maintain discipline inside the school campus as well as the school premises when students are engaged in activities authorized by the school. As stated in paragraph 2, Section 6.2, Rule VI from Rules and Regulations of RA 9155 as mentioned in DepEd Order No. 1, s. 2003, the school head shall have authority, accountability, and responsibility for creating an environment within the school that is conducive to teaching and learning. Thus, school officials and teachers shall have the right to impose appropriate and reasonable disciplinary measures in case of minor offenses or infractions of good discipline. Discipline may be one of the solutions in addressing prevalent disruptive behaviors. There shall be a committee, which will handle grave/major offenses as stated in the 2000 DECS Service Manual. They shall be composed of a chair, co-chair, and member. The school principal shall designate a school disciplinary officer per curriculum year level. He/she shall also designate curriculum chairman and class adviser per curriculum year level. All cases beyond the control and expertise of the School Discipline Committee shall be referred to the Office of the Principal and Guidance Counseling and furnish a copy of the referral form attached with the anecdotal report and other supporting documents for more extensive supervision and control. A standard intervention plan for managing classroom disruptive behaviors may be proposed. Research Questions 1. What is the demographic profile of the students in terms of: 1.1 Age 1.2 Sex 1.3 Grade Level 2. What are the prevalent disruptive classroom behaviors? 3. Is there a significant relationship between the profile of the students and the prevalent disruptive behaviors? 4. What are the intervention plan or strategies being used by the teachers? 5. Based on the findings, what standard intervention plan in managing classroom disruptive behaviors may be proposed? Scope and Limitation This research will involve the Grade 7 students in Tropical Village National High School enrolled for School Year 2022-2023. Guidance Teachers and Grade level teachers will help the researcher in observing the students and answering the disruptive behavior checklist and participate in the interview regarding current intervention programs/action plan or classroom strategies in handling disruptive behavior. Data gathering will last for 4 weeks. Research Methodology a. Sampling PURPOSIVE SAMPLING - Grade 7 Junior High School students in Tropical Village National High School. b. Data Collection - Profiling of students - Adapted Disruptive Behaviors in Classroom Checklist (It will undergo validation by experts.) - FGD c. Ethical Issues The hazards associated with this study are extremely low. The IATF protocol will be properly followed. The subjects will incur no costs other than their time, and there will be no risk of bodily harm. The communication costs will be deducted from the requested research budget. The researchers cannot anticipate any risk other than the subjects considering issues they may never have considered before. Because participation in the data collection will be anonymous, obtaining consent from respondents will not be a difficulty. Only the researchers will have access to the information. d. Plan for Data Analysis Quantitative/Qualitative (Mixed Method) Statistical Treatment SOP1 - Frequency count SOP2 - Frequency Count ( Checklist) SOP3 - Chi-Square SOP 4- FGD Timetable/Gantt Chart ACTIVITIES 1. Submit a copy of the research to the Regional and Division offices *Month 1 Mont h2 Mont h3 Month 4 Month 5 Month 6 2. Submit a copy of the research to schools in General Trias City, Cavite. 3. Join different FGDs 4. Present the result during seminars/training/mee tings. 5. Join different research forums *Shade the corresponding month per activity Plans for Dissemination and Utilization JUNE JULY DISSEMINATION ACTIVITIES 1. Submit a copy of the research to the Regional and Division offices 2. Submit a copy of the research to schools in General Trias City, Cavite. 3. Join different FGDs 4. Present the result during seminars/training/ meetings. 5. Join different research forums *Shade the corresponding month per activity AUGUST SEP TEM BER OCTOB ER NOVEM BER References Araban, M., Montazeri, A., Stein, L. A., Karimy, M., & Mehrizi, A. A. (2020). Prevalence and factors associated with disruptive behavior among Iranian students during 2015: A cross-sectional study. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 46(1). doi:10.1186/s13052-020-00848-x Yusoff, W. M. W., & Mansor, N. (2016). The effectiveness of strategies used by teachers to manage disruptive classroom behaviors: A case study at a religious school in Rawang, Selangor, Malaysia. IIUM Journal of Educational Studies, 4(1), 133-50. SUBMITTED BY: IRENE M. DULAY