Handbook of Research Ethics in Psychological Science

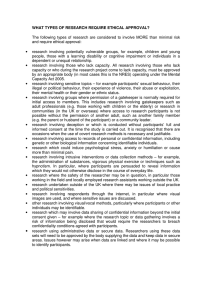

advertisement