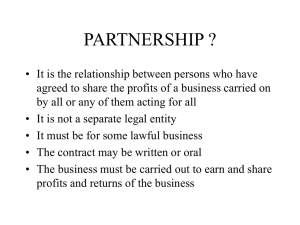

Partnership Law Introduction: Historical Development & Legal Frameworks

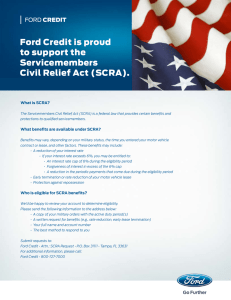

advertisement