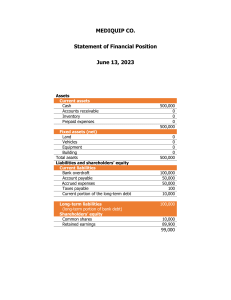

Review of Finance (2013) 17: pp. 1827–1852 doi:10.1093/rof/rfs043 Advance Access publication: January 12, 2013 ROBERT KIESCHNICK1, MARK LAPLANTE2 and RABIH MOUSSAWI3 1 School of Management, University of Texas at Dallas, 2Terry College of Business, University of Georgia, and 3Wharton Research Data Services, University of Pennsylvania Abstract. We provide the first empirical study of the relationship between corporate working capital management and shareholders’ wealth. Examining US corporations from 1990 through 2006, we find evidence that: the incremental dollar invested in net operating working capital is worth less than the incremental dollar held in cash for the average firm; the valuation of the incremental dollar invested in net operating working capital is significantly influenced by a firm’s future sales expectations, its debt load, its financial constraints, and its bankruptcy risk; and the value of the incremental dollar extended in credit to one’s customers has a greater effect on shareholders’ wealth than the incremental dollar invested in inventories for the average firm. JEL Classification: G31, G34 1. Introduction Many corporate financial officers identify working capital management as being very important to their firms’ value. This importance is implied by the fact that a substantial portion of most firms’ assets, >27% on average for US corporations in our sample, is tied up in net operating working capital. Reflecting this importance, CFO Magazine sponsors and reports on an annual study of corporate working capital management performance, both in the USA and other countries. Such studies typically consider working capital management to imply the management of a firm’s accounts receivable, accounts payable, and inventories. While there are empirical studies of individual aspects of working capital management (e.g., Petersen and Rajan, 1997 on trade credit), there * We thank seminar participants at Baylor University, the University of Texas at Dallas, and the FMA meetings for comments on earlier drafts. We especially want to thank Alexander Butler, Matthew Hill, and our referee for their comments on prior drafts. ß The Authors 2013. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Finance Association. All rights reserved. For Permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oup.com Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 Working Capital Management and Shareholders’ Wealth* 1828 R. KIESCHNICK ET AL. 1 A typical textbook definition of a firm’s cash conversion cycle is 365 (accounts receivable/ sales þ inventory/sales accounts payable/cost of goods sold). 2 Hill, Kelly, and Highfield (2010) provide a recent examination of the factors that significantly influence corporate investment in net operating working capital. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 is scant research on the integrated working capital concept that is the focus of both industry studies (e.g., REL Consultancy, 2005, etc.) and earlier academic studies (e.g., Schiff and Lieber, 1974, etc.). Probably the earliest integrated working capital concept is the cash conversion cycle—the time lag between the expenditure for the purchase of raw materials and the collection from the sale of finished goods—which is often viewed as the key measure of working capital management performance (e.g., Gitman, 1974).1 The cash conversion cycle, despite the acronym, is not about cash management, but it is about the firm’s management of its net operating working capital. As such, it concerns the management of receivables, the management of inventories, and the use of trade credit. In other words, the firm’s net operating working capital.2 Despite the fact that corporate financial executives consider net operating working capital management to be an important determinant of firm value, we know of no published empirical studies of this relationship. Consequently, we provide the first such examination for US corporations. To do this, we examine net working capital investments in a comprehensive sample of US corporations between 1990 through 2006. We find evidence for the following conclusions. First, for the average firm, the incremental dollar invested in net operating capital is worth less than the incremental dollar held in cash. Second, conditional on current levels of investment, the value of an additional dollar invested in net operating working capital is worth less than the dollar so invested for the average firm. Third, the value of an additional dollar invested in net operating working capital is significantly influenced by a firm’s future sales expectations, its debt load, its financial constraints, and its bankruptcy risk. This evidence implies that an additional dollar is worth much less in financially unconstrained firms with high debt loads and poor sales growth prospects. Fourth, for the average firm, the incremental dollar invested in credit to one’s customers has a much greater effect on shareholders’ wealth than incremental dollar invested in inventories, and so suggests that a firm’s trade credit policies are very important part of its working capital management. Altogether our evidence illuminates the importance of working capital management to shareholders and the subtle effects of financing on its wealth effects. We organize our study as follows. In the next section, Section 2, we provide a brief review of what prior literature has said about the relationship WORKING CAPITAL MANAGEMENT AND SHAREHOLDERS’ WEALTH 1829 2. Review of Prior Literature and Identification of Key Issues Prior empirical literature on working capital management has focused primarily on its effects on firm profitability, which influences corporate valuations. For example, Soenen (1993), Shin and Soenen (1998), Deloof (2003), and Garcia-Teruel and Martinez-Solano (2007) provide evidence that the profitability of a firm, measured by either return on assets or return on equity, is improved as the firm improves its management of its working capital (i.e., the profitability of a firm is inversely related to its cash conversion cycle).3 While such studies suggest that firms that minimize their investment in net operating capital will maximize their profitability and thereby firm value; this last inference does not necessarily follow. To see this more clearly, we use the standard free cash flow (FCF) valuation model, which accounts for a firm’s investment in its net operating working capital. For example, Brigham and Davies (2007) or Ehrhardt and Brigham (2009) provide the following expression for the value of a firm: Vfirm ¼ 1 X t¼1 FCFt ð1 þ WACCÞt ð1Þ where FCFt ¼ NOPATt – DNOWCt – DFixed Assetst, NOPATt is the net operating profit after tax at time t, DNOWCt is the investment in net operating working capital, and DFixed Assetst is the investment in long-term assets. While this expression makes it clear that investment in net operating working capital is an important determinant of firm value, it does not make it clear what its relationship is because investments in net operating work capital are like investments in long-term assets in that they reduce current free cash flow while influencing future free cash flows. 3 Unfortunately these studies fail to recognize that this relationship is implied by the DuPont equation. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 between working capital management and firm value. Section 3 describes our sample and data. In Section 4, we present our baseline analysis of the effect of investment in net operating working capital on shareholders’ wealth. In Section 5, we analyze how different factors influence the effect of incremental investments in net operating working capital on shareholders’ wealth. Section 6 examines how each component of net operating working capital influences shareholders’ wealth. Finally, we conclude with a summary of our findings and implications for future research. 1830 R. KIESCHNICK ET AL. NPVt ¼ ½PP þ PD þ PCSt where : PP ¼ Cp ertp , PD ¼ ð1 dÞqertd , PC ¼ ð1 qÞð1 bÞertc ð2Þ and where Cp represents cash paid for production, d represents the discount on sales, q represents the fraction of sales on credit, b represents the percentage of bad credit sales, St represent the sales at time t, r the discount rate, 4 Corsten and Gruen estimate that for a billion dollar retail chain, this would imply about $40 million in lost sales per year. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 To illustrate why such investments influence future free cash flows, Wadsworth and Bryan (1974) provide an example of how the failure to have products on hand for customers influences future sales, so firms will choose to reduce their current profitability to reflect this cost. In the supply chain literature, this is called stock-outs and it is a significant concern. For example, Corsten and Gruen (2004) provide evidence that between 21% and 43% of a firm’s customers (depending on product category) faced with a stock-out will go to another store.4 So, current investment in inventories has future revenue implications. However, inventory management should not really be separated from other elements of the net operating working capital concept for a variety of reasons. For example, Schiff and Lieber (1974) point out that a firm’s credit policy and inventory management are fundamentally linked. To illustrate this linkage, they provide a dynamic optimization model that shows how credit policy and inventory management influence one another over time. Intuitively, extending more trade credit to one’s customers increases sales and the need for more inventory investment. Extending less trade credit works in the opposite direction. Reflecting the need for an integrative view, Sartoris and Hill (1983) and Kim and Chung (1990) provide models that focus on how the joint management of a firm’s credit policies and inventories influences firm value. Each of these models brings up the importance of considering all components concurrently because they influence each other. Of particularly relevance to our study, these integrative models emphasize the importance of sales growth and financing to the relationship between working capital management and firm value, which is missing in the literature on the relationship between working capital management and firm profitability. To illustrate, Sartoris and Hill (1983) derive the following basic representation for the net present value associated with inventory and credit policy decisions: WORKING CAPITAL MANAGEMENT AND SHAREHOLDERS’ WEALTH 1831 and tp, td, and tc represent the timing of the cash payments. Given this expression, Sartoris and Hill then represent its effect on firm value as: NPV ¼ ðPP þ PD þ PCÞS0 fðtÞert dt ð3Þ 0 where N represents the planning horizon and f(t) represents a function describing the time path of sales. This expression makes it clear that both the firm’s future sales growth and its opportunity cost of financing play critical roles in the valuation effects of a firm’s credit and inventory management. To illustrate the effect of an additional dollar invested in net working capital work, we can use the free cash flow version of the above equation and imagine an incremental investment of one dollar in net operating capital that is made in perpetuity. Based on our sample, we estimate the resulting increment in future free cash flow to be roughly $0.05 and so with a cost of capital of 6.5%, this would represent an increase in firm value to roughly $0.73.5 However, this literature still misses the richness of the effects of financing investments in these assets. A particularly instructive illustration of this is given in Shin and Soenen (1998). Wal-Mart and Kmart had similar capital structures in 1994, Kmart had a cash conversion cycle of roughly 61 days, whereas Wal-Mart had a cash conversion cycle of 40 days. Assuming a 10% cost of capital, Kmart faced an additional $198.3 million or so per year in financing costs.6 Ultimately, Kmart went bankrupt, which was attributed in part to the financial costs of its poor working capital management practices as these costs contributed to its losses.7 The implied relationship between investment in net operating working capital and financing raises the issue of how financing influences the valuation effects of investment in net operating working capital. Unfortunately, the typical characterizations of this relationship in the literature are not sufficiently rich to judge. For example, both Beranek (1967) and Haley 5 For our sample, an increment in net working capital in year t is associated with an increment in free cash flow the next year of roughly 0.05. One needs to recognize that free cash flow is a net cash flow rather than gross cash flow concept. So, an additional dollar of sales today paid in cash only generates $0.10 in net operating profit after tax with a cost of goods sold of $0.84 and a tax rate of 35%. 6 Shin and Soenen (1998, p. 37). 7 By and large, increases in net operating working capital are financed by external debt capital. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 ZN 1832 R. KIESCHNICK ET AL. 3. Sample To address the focus of our study, we examine a sample of US public corporations from 1990 through 2006. We begin by identifying all US corporations with Compustat and Center for Research on Security Prices (CRSP) data over this time period. Next, we exclude all firms in the financial service industries (SIC 6000–SIC 6800) as working capital has a very different meaning in these industries. Our final sample consists of 3,786 companies per year on an average. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 and Higgins (1973) point out that carrying costs and opportunity costs are not the same and that ordering decisions and financing decisions affect one another. Despite these observations, a perusal of many recent supply chain models reveals that this distinction is not often recognized. The likely effects of financing, particularly debt financing, on investment in net operating working capital raises questions about the effect of monetary policy and financial market conditions on the extension of trade credit and on the valuation of investments in net operating working capital. Meltzer (1960) argues that when monetary policy is tight, large firms use their liquid balance to extend credit to small firms, who may face credit rationing. In a similar, but different vein, Lewellen, McConnell, and Scott (1980) recognized that in perfectly competitive markets with perfect capital markets, trade credit is irrelevant to firm value. Lewellen, McConnell, and Scott then went on to demonstrate how different capital market imperfections make the use of trade credit relevant to firm value. Consistent with these arguments, Danielson and Scott (2004) and Petersen and Rajan (1997) provide evidence that firms facing financial constraints are particularly dependent on the use of trade credit to finance their current operations. To summarize, a survey of the prior literature on the relationship between working capital management and firm value suggests that: (i) one needs to consider a firm’s management of its accounts receivable, accounts payable, and inventory jointly; (ii) the linkage between net operating working capital management and firm value can differ from that between net operating working capital management and firm profitability because of the effect of working capital management on future sales; (iii) a firm’s expected sales growth will be an important influence on the valuation effects of investment in net operating working capital; (iv) financing, particularly debt financing, influences the profitability of investment in working capital; and (v) credit rationing and/or financial constraints may significantly influence the valuation of investment in net operating working capital. WORKING CAPITAL MANAGEMENT AND SHAREHOLDERS’ WEALTH 1833 4. The Effect of Net Operating Working Capital Investment on Firm Value We begin our empirical study by examining the valuation effects of investments in net operating working capital. To do this, we use Faulkender and Wang (2006) to form our baseline valuation model. They provide reasons why an excess stock returns approach is a better way of measuring valuation effects than is a market-to-book ratio approach (e.g., Fama and French, 1998). To see its relationship to our earlier firm valuation model, note that we can rewrite the FCF model as an equity residual cash flow (ERCF) model: Vequity ¼ 1 X ERCFt ð1 þ re Þt t¼1 ð4Þ where ERCFt ¼ FCFt – Net Cash flows to nonequity holders, and re represents the cost of equity capital. Within this framework, the firm increases shareholders’ wealth only if it generates excess returns to equity. Thus, we can judge the effects of investment in net operating working capital by judging its effects on the excess returns to equity holders. Faulkender and Wang (2006) focus on what might influence excess returns to equity and specify the following type of model: rt RBt ¼ 0 þ 1 CðtÞ þ 2 Cðt 1Þ þ 3 EðtÞ þ 4 NAðtÞ þ 5 RDðtÞ þ 6 IðtÞ þ 7 DðtÞ þ 8 LðtÞ þ 9 NFðtÞ þ "t , ð5Þ where the dependent variable,rt RBt , represents a stock’s excess return during the 12 months ending at fiscal period end of year t, where rt is the realized return on the firm’s stock during the fiscal year t, and RBt is the benchmark return for the stock. This model is like a hedonic price Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 For each of these firms, we collect stock return data from CRSP and accounting data from Compustat. More will be said about the variables created from these data below. It is important to note that the median percentage of total asset accounted for by either operating working capital (accounts receivable plus inventories) or net operating working capital (accounts receivable plus inventories minus accounts payable) is 37.6% and 27.7%, respectively. We draw the reader’s attention to these facts as they illustrate why many firms stress the importance of working capital management to their firm’s performance since they account for a substantial portion of their assets. 1834 R. KIESCHNICK ET AL. 8 Fraulkender and Wang (2006) extensively discuss the motivation for their specification and so we will not repeat their discussion. 9 It is worth noting that we examine the robustness of our conclusions to a change in the benchmark return by using the CRSP value-weighted index return and derive the same basic conclusions. 10 We winsorize rather than trim observations, as done in other studies, because we do not think that trimming is appropriate if the concern is over data entry errors. As a result, there will be differences between our summary statistics and baseline coefficient estimates and those reported in Dittmar and Mahrt-Smith (2007), for example, which covers a similar time period. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 equation in that it relates excess stock returns (value) to firm characteristics that influence cash flows to stockholders.8 Following Faulkender and Wang (2006), we define each of the variables in Equation (5) as follows. rt RBt represents the firm’s benchmark-adjusted stock return where the benchmark return is the return of a size and book-to-market sorted portfolio for which the stock belongs. A CRSP and Compustat merged database is used to sort stocks every month into size and book-to-market quintiles to construct twenty-five benchmark portfolios and their returns following Daniel and Titman (1997).9 C(t) represents the firm’s cash holdings. I(t) represents the firm’s interest expense. D(t) represents the firm’s total dividends. L(t) represents the firm’s market leverage (total debt over total debt plus the market value of equity, MVE). NF(t) represents the firm’s net financing (total equity issuance minus repurchases plus debt issuance minus debt redemption) during the fiscal year. E(t) represents the firm’s earnings before interest and extraordinary items. NA(t) represents the firm’s total assets net of cash. RD(t) represents the firm’s R&D expenditures (zero if missing). We use the notation, X, for unexpected changes in X over the current year. Faulkender and Wang (2006) find that using actual changes in X provide similar estimates to various expected change estimates and so we will use actual changes as well. We then divide each of these variables, except L(t), by the firm’s MVE at the beginning of the fiscal year, so that X(t) is the level of variable X in year t divided by the firm’s MVE in year t 1. Due to this scaling by market capitalization at t 1, the regression coefficients are a gage for how investors perceive each $1 investment in X; measured relatively to how *X is able to explain the unanticipated change in a company’s valuation ((rt RBt )*MVEt 1). Summary statistics for each of these variables are reported in Table I. Note that we winsorize each variable based on Compustat data at the 1% and 99% levels.10 In Table II, we report the pairwise correlations between all the variables used in our study. We do not observe any correlations that WORKING CAPITAL MANAGEMENT AND SHAREHOLDERS’ WEALTH 1835 Table I. Basic summary statistics ri, t RBi, t Ct Ct 1 Et NAt NNAt RDt It Dt Lt NFt NWCt 1 NWCt Past sales growth Future sale growth Short-term debt Altman Z* SA Index Libor Term spread Credit spread Real GDP growth Stock mkt volatility Mean Median (SD) 0.230 0.007 0.173 0.010 0.069 0.048 0.001 0.001 0.0002 0.219 0.007 0.406 0.010 5.7954 2.1528 0.0953 5.5729 1.2057 4.727 1.7360 0.8188 2.9154 0.6955 0.051 (0.961) 0.0008 (0.154) 0.087 (0.241) 0.007 (0.239) 0.041 (0.505) 0.020 (0.340) 0.000 (0.025) 0.000 (0.030) 0.000 (0.039) 0.141 (0.235) 0.000 (0.344) 0.009 (0.183) 0.087 (0.183) 277.2458 (0.3362) 84.6707 (0.2619) 0.1453 (0.0341) 15.7868 (3.6854) 1.8643 (1.1734) 5.42 (1.803) 1.0499 (1.4325) 0.1851 (0.7650) 1.2392 (3.2710) 0.6129 (0.2517) Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 Following Faulkender and Wang (2006), we compute excess stock returns, ri, t RBi,t , using the characteristics benchmarks. Ct is cash plus marketable securities; Et is earnings before extraordinary items plus interest, deferred tax credits, and investment tax credits; NAt is the total assets minus cash holding; NNAt is the total assets minus cash holdings and net operating working capital; Dt is the common dividends paid; It is the interest expense; Lt is the market leverage; NFt is the total equity issuance minus repurchases plus debt issuance minus debt redemption; RDt is R&D expenditures, which is set to zero if missing; NWCt is the accounts receivable plus inventory minus accounts payable. Past sales growth represents the firm’s sales growth over the past 3 years. Future sales growth represents the firm’s sales growth over the next 3 years. Short-term debt is the ratio of debt in current liabilities to total liabilities. Altman’s Z is the firm’s original Altman Z-score for the prior year. The SA index is Hadlock and Pierce’s (2010) constraint index. Libor represents the average 3 month Libor rate over the year. Term spread is the average difference between the 10 year and 90 day Treasuries. Credit spread is the average difference between AA and BB rated bonds. Real gross domestic product (GDP) Growth Rate is the inflation-adjusted GDP growth rate. Stock mkt volatility is the standard deviation of the CRSP equally weighted daily stock returns over the year. X represents 1 year changes (i.e., Xt – Xt 1). All variables based upon Compustat data are winsorized at the 1% and 99% level. All variables reported above the double bars, except Lt and excess stock returns, are deflated by the lagged MVE, Mt 1. Variables reported below the double bars are not adjusted by the MVE. 1836 R. KIESCHNICK ET AL. Table II. Raw correlations among variables ri, t RBi,t Ct Ct 1 Et NAt NNAt RDt It Dt Lt NFt NWCt 1 NWCt Past sales growth Future sale growth Short-term debt Altman Z* SA Index Libor Term spread Credit spread Real GDP Growth Stock mkt volatility ri, t RBi,t Ct Ct 1 Et NAt NNAt RDt It 1.000 0.215 0.091 0.242 0.133 0.084 0.032 0.049 0.026 0.105 0.198 0.029 0.118 0.027 0.003 0.047 0.110 0.114 0.019 0.004 0.034 0.038 0.042 1.000 0.186 0.136 0.039 0.008 0.028 0.001 0.010 0.175 0.043 0.052 0.092 0.019 0.002 0.062 0.035 0.026 0.020 0.006 0.042 0.035 0.018 1.000 0.075 0.029 0.031 0.056 0.045 0.011 0.057 0.128 0.217 0.013 0.003 0.001 0.059 0.025 0.119 0.064 0.030 0.068 0.060 0.011 1.000 0.165 0.078 0.126 0.010 0.034 0.008 0.031 0.070 0.194 0.006 0.010 0.044 0.003 0.024 0.049 0.004 0.015 0.040 0.015 1.000 0.819 0.140 0.426 0.034 0.326 0.029 0.133 0.672 0.012 0.000 0.038 0.000 0.084 0.037 0.085 0.034 0.083 0.064 1.000 0.100 0.386 0.022 0.325 0.045 0.118 0.252 0.014 0.002 0.067 0.003 0.103 0.047 0.068 0.009 0.036 0.048 1.000 0.053 0.014 0.038 0.049 0.042 0.132 0.005 0.002 0.020 0.031 0.021 0.041 0.032 0.006 0.016 0.035 1.000 0.018 0.025 0.200 0.050 0.290 0.007 0.000 0.067 0.018 0.049 0.072 0.195 0.045 0.040 0.011 (continued) Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 Following Faulkender and Wang (2006), we compute excess stock returns, ri, t RBi,t , using the characteristics benchmarks. Ct is the cash plus marketable securities; Et is the earnings before extraordinary items plus interest, deferred tax credits, and investment tax credits; NAt is the total assets minus cash holding; NNAt is the total assets minus cash holdings and net operating working capital; Dt is the common dividends paid; It is the interest expense; Lt is the market leverage; NFt is the total equity issuance minus repurchases plus debt issuance minus debt redemption; RDt is the R&D expenditures, which is set to zero if missing; NWCt is the accounts receivable plus inventory minus accounts payable. Past sales growth represents the firm’s sales growth over the past 3 years. Future sales growth represents the firm’s sales growth over the next 3 years. Short-term debt is the ratio of debt in current liabilities to total liabilities. Altman’s Z is the firm’s original Altman Z-score for the prior year. The SA index is Hadlock and Pierce’s (2010) constraint index. Libor represents the average 3 month Libor rate over the year. Term spread is the average difference between the 10 year and 90 day Treasuries. Credit spread is the average difference between AA and BB rated bonds. Real GDP growth rate is the inflation-adjusted GDP growth rate. Stock mkt volatility is the standard deviation of the CRSP equally weighted daily stock returns over the year. X represents 1 year changes (i.e., Xt – Xt 1). All variables based upon Compustat data are winsorized at the 1% and 99% level and are deflated by the lagged MVE, Mt 1 (except Lt). WORKING CAPITAL MANAGEMENT AND SHAREHOLDERS’ WEALTH 1837 Table II. (Continued) Dt Lt NFt NWCt 1 NWCt Past sales growth Future sale growth Short-term debt Altman Z* SA Index Libor Term spread Credit spread Real GDP growth Stock mtk volatility Altman Z* SA Index Libor Term spread Credit spread Real GDP Growth Stock mkt volatility Ct Ct 1 Et NAt NNAt RDt It 1.000 0.215 0.091 0.242 0.133 0.084 0.032 0.049 0.026 0.105 0.198 0.029 0.118 0.027 0.003 0.047 0.110 0.114 0.019 0.004 0.034 0.038 0.042 1.000 0.186 0.136 0.039 0.008 0.028 0.001 0.010 0.175 0.043 0.052 0.092 0.019 0.002 0.062 0.035 0.026 0.020 0.006 0.042 0.035 0.018 1.000 0.075 0.029 0.031 0.056 0.045 0.011 0.057 0.128 0.217 0.013 0.003 0.001 0.059 0.025 0.119 0.064 0.030 0.068 0.060 0.011 1.000 0.165 0.078 0.126 0.010 0.034 0.008 0.031 0.070 0.194 0.006 0.010 0.044 0.003 0.024 0.049 0.004 0.015 0.040 0.015 1.000 0.819 0.140 0.426 0.034 0.326 0.029 0.133 0.672 0.012 0.000 0.038 0.000 0.084 0.037 0.085 0.034 0.083 0.064 1.000 0.100 0.386 0.022 0.325 0.045 0.118 0.252 0.014 0.002 0.067 0.003 0.103 0.047 0.068 0.009 0.036 0.048 1.000 0.053 0.014 0.038 0.049 0.042 0.132 0.005 0.002 0.020 0.031 0.021 0.041 0.032 0.006 0.016 0.035 1.000 0.018 0.025 0.200 0.050 0.290 0.007 0.000 0.067 0.018 0.049 0.072 0.195 0.045 0.040 0.011 Dt Lt NFt NWCt 1 NWCt Past sales growth Future sale growth Short-term debt 1.000 0.075 0.047 0.030 0.033 0.000 0.000 0.025 0.004 0.018 0.001 0.012 0.001 0.052 0.037 1.000 0.036 0.070 0.204 0.017 0.005 0.045 0.016 0.004 0.101 0.007 0.018 0.022 0.049 1.000 0.513 0.001 0.006 0.003 0.269 0.155 0.137 0.102 0.128 0.094 0.039 0.041 1.000 0.121 0.009 0.009 0.221 0.066 0.036 0.060 0.072 0.188 0.126 0.043 1.000 0.004 0.002 0.026 0.005 0.026 0.011 0.071 0.043 0.096 0.053 1.000 0.000 0.002 0.001 0.007 0.005 0.003 0.005 0.001 0.0001 1.000 0.002 0.003 0.006 0.008 0.002 0.005 0.004 0.0001 1.000 0.064 0.224 0.091 0.035 0.023 0.001 0.048 Altman Z* SA Index Libor Term spread Credit spread Real GDP growth Stock mkt volatility 1.000 0.066 0.011 0.006 0.012 0.007 0.025 1.000 0.121 0.014 0.026 0.007 0.115 1.000 0.524 0.584 0.122 0.132 1.000 0.112 0.086 0.341 1.000 0.409 0.286 1.000 0.116 1.000 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 ri, t RBi,t Ct Ct 1 Et NAt NNAt RDt It Dt Lt NFt NWCt 1 NWCt Past sales growth Future sale growth Short-term debt Altman Z* SA Index Libor Term spread Credit spread Real GDP Growth Stock mkt volatility ri, t RBi,t 1838 R. KIESCHNICK ET AL. rt RBt ¼ 0 þ 1 CðtÞ þ 2 Cðt 1Þ þ 3 EðtÞ þ 4 NNAðtÞ þ 5 RDðtÞ þ 6 IðtÞ þ 7 DðtÞ þ 8 LðtÞ þ 9 NFðtÞ ð6Þ þ 10 NWCtþ1 þ 11 NWCt þ "t , where NWC represents net operating working capital and NNA(t) represents total assets less the sum of cash and marketable securities and net operating working capital. As noted earlier, this should capture the effects of investments in net operating working capital on shareholders’ wealth. With these expectations in mind, we report the results of estimating Equation (6) in Column 3 (Model 2) of Table III.11 This evidence suggests that for a firm with average characteristics, an additional $1 invested in net operating working capital is valued by shareholders at about $0.52, which is less than the dollar so invested and substantially less than the $1.49 valuation being put on an incremental dollar in cash and marketable securities during this period. Interestingly, this evidence is consistent with the evidence in Autukaite and Molay (2011) for French companies. Both of our results make clear why firms worry so much about their working capital management. 11 We, like Faulkender and Wang (2006) and Dittmar and Mahrt-Smith (2007), estimate our model as a random effects model. We tested for its appropriateness relative to a fixed effects model using a Hausman’s test and fail to reject its applicability. We also tested for the inclusion of various industry adjustments and do not derive different implications. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 would suggest that multicollinearity is a concern. This evidence will become important when we consider certain interactions. Given these data, we now estimate a baseline valuation model that mirrors Column 1 of Table II in Faulkender and Wang (2006) and reflects Equation (5) above. We report these results in Column 2 (Model 1) of Table III. The signs and significance of the different coefficients are consistent with those reported in Faulkender and Wang (2006). However, where they estimate that shareholders value an extra dollar of cash at $0.75, we estimate that shareholders value an extra dollar of cash at $1.53, which suggests that the incremental value of a dollar changes over time since we study different time periods. Such a conjecture is consistent with Dittmar and Mahrt-Smith’s (2007) evidence, who also observe a similar coefficient increase for a comparable sample period. Given this benchmark estimation, we now focus on the effect of net operating working capital investment on shareholders’ wealth while accounting for its prior level. To do this, we incorporate NWCt 1 and DNWCt in Equation (5) and adjust our measurement of net assets to derive. WORKING CAPITAL MANAGEMENT AND SHAREHOLDERS’ WEALTH 1839 Table III. The effect of net operating working capital on shareholders’ wealth Constant Ct 1 DCt Et NAt Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 0.199 (0.00) 0.725 (0.00) 1.526 (0.00) 0.640 (0.00) 0.200 (0.00) 0.177 (0.00) 0.694 (0.00) 1.491 (0.00) 0.551 (0.00) 0.178 (0.00) 0.689 (0.00) 1.494 (0.00) 0.549 (0.00) 0.210 (0.00) 0.867 (0.00) 0.442 (0.03) 0.101 (0.26) 0.952 (0.00) 0.126 (0.00) 0.282 (0.00) 0.518 (0.00) 0.198 (0.00) 0.806 (0.00) 0.338 (0.10) 0.111 (0.21) 0.954 (0.00) 0.125 (0.00) 0.269 (0.00) 0.775 (0.00) 0.163 (0.00) 58385 0.19 NNAt DRDt DIt DDt Lt NFt 0.992 (0.00) 1.405 (0.00) 0.027 (0.77) 0.548 (0.00) 0.134 (0.00) NWCt 1 DNWCt NWCt 1 * DNWCt Observations R2 58385 0.17 58385 0.19 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 Following Faulkender and Wang (2006), we regress the excess stock returns on changes in firm characteristics over the fiscal year. All variables except Lt and excess stock returns are deflated by the lagged MVE, Mt 1. Ct is the cash plus marketable securities; Et is the earnings before extraordinary items plus interest, deferred tax credits, and investment tax credits; NAt is the total assets minus cash holding; NNAt is the total assets minus cash holdings and net operating working capital; Dt is the common dividends paid; It is the interest expense; Lt is the market leverage; NFt is the total equity issuance minus repurchases plus debt issuance minus debt redemption; RDt is the R&D expenditures, which is set to zero if missing; NWCt is the accounts receivable plus inventory minus accounts payable. X represents 1 year changes (i.e., Xt – Xt 1). All variables based upon Compustat data were winsorized at the 1% and 99% level. Each regression model is estimated as a random effects model and uses Roger standard errors adjusted for clustering at the firm level. p-Values associated with the null hypothesis that the coefficient equals zero are reported within parentheses. 1840 R. KIESCHNICK ET AL. 5. The Effect of Different Factors on the Incremental Value of Investments in Net Operating Working Capital to Shareholders In Section 4, we examined the effects on shareholders’ wealth of an additional dollar invested in net operating working capital. We found that this effect was influenced by a firm’s current level of net operating working capital. This evidence raises the question of how other relevant factors, some of which were discussed in Section 2, might influence the valuation effects of an additional investment in net operating working capital. To address this issue, we now expand our analysis to consider other possible influences on the value of an additional dollar invested in net operating working capital. The influences that we consider and their rationale are as follows. 5.1 EXPECTED SALES GROWTH The models of Schiff and Lieber (1974), Sartoris and Hill (1983), and Kim and Chung (1990) all suggest that investments in net operating working capital should be more valuable the greater the expected future sales of the firm. This expectation is consistent with textbook treatments of such investments that emphasize the idea that you must have product on hand to sell, not only for current sales but also to influence the future sales. Consequently, we should expect investments in net operating working capital to be more valuable in firms with greater expected sales growth. Once again, however, we have no prior evidence on this relationship and Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 Expanding on this point, we next examine the interaction between NWCt 1 and DNWCt as it captures the valuation effects of an additional dollar invested in net operating working capital conditional on the current levels of investment in net operating working capital. Industry surveys (e.g., ITworld.com, 2002; REL Consultancy, 2005) suggest that the coefficient of this interaction should be negative. Examining the results of estimating the implied revised regression model (Model 3) in Column 4, we do observe a significantly negative coefficient. This estimate suggests that at average levels of investment in net operating working capital, its incremental value is diminishing at the rate of $0.16 per additional invested dollar. This evidence also appears consistent with the marginal valuation argument of working capital investment in Fazzari and Petersen (1993). Regardless, our evidence makes clear to the shareholders the importance of a firm managing its net operating working capital as efficiently as possible. WORKING CAPITAL MANAGEMENT AND SHAREHOLDERS’ WEALTH 1841 5.2 DEBT LOAD The value to shareholders of an additional dollar invested is expected to be influenced by the firm’s use of debt financing. Preve and Sarria-Allende (2010) discuss the important role of debt maturity decisions in the financing of working capital, as short-term financing alternatives might not always be available for the firm at a reasonable cost. Preve and Sarria-Allende (2010) warn that suboptimal financing patterns due to a mismatch between the maturity of assets and liabilities could cause the company to face liquidity problems that might precipitate default and financial troubles. To capture these effects, we consider the use of long- and short-term debt separately as each may play a different role. 5.3 LONG-TERM DEBT Since our leverage (Lt) measure captures a firm’s use of long-term debt, we use it to capture the effects of long-term debt on how an incremental dollar in net operating working capital influences shareholders’ wealth. 5.4 SHORT-TERM DEBT To capture the effects of the firm’s use of short-term debt, we use the ratio of the firm’s debt in current liabilities to its total liabilities. 5.5 BANKRUPTCY RISK As a firm faces an increasing likelihood of bankruptcy, investments in net operating working capital may be valued either more or less. If easily Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 so simply examine what effect expected sales growth has on the valuation effects of investment in net operating working capital. Unfortunately, there is no simple way to measure the market’s expectations about a firm’s future sales growth. Consequently, we explore two measures. For our first measure, we compute each sample firm’s sales growth rate over the prior 3 years. If the market uses a firm’s past growth rate to forecast its future sales growth rate, then this measure is a reasonable proxy for the market’s expectations about a firm’s future sales growth. For our second measure, we use the firm’s growth rate over the future 3 years as a proxy for the market’s expectations for its sales growth rate under the assumption that the market forms unbiased forecasts of a firm’s future sales growth rate. 1842 R. KIESCHNICK ET AL. 5.6 FINANCIAL CONSTRAINTS The effects of a firm facing financial constraints are two-fold. If a firm faces financial constraints, then its access to credit markets is more limited and its funds are more expensive. To the extent that increased debt expense reduces excess shareholders’ returns, then the net operating working capital investments of financially constrained firms should be less valued.12 However, given the evidence in Petersen and Rajan (1997), we might expect that firms that face fewer financial constraints to offer more credit to their customers and use less trade credit. Further, given the evidence in Carpenter, Fazzari, and Petersen (1998), we expect firms that face fewer financial constraints to invest more in inventories. Whether these increased investments in net operating working capital will be valued more or less is unclear. There are several indicia of the degree to which a firm faces financial constraints. Some of these measures use leverage, earnings, and other variables that we already incorporate in our base specification. Further, Hadlock and Pierce (2010) provide evidence that questions the extent to which such variables measure the degree to which a firm is financially constrained. As a consequence, they develop an index that they show to be superior to prior measures and so we use their SA Index. Their index is computed as: (0.737*Size) þ (0.043*Size2) – (0.040*Age), where size is the log of inflation 12 Note that this relationship is supported by the significantly negative coefficient on a firm’s leverage ratio in Table III. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 liquidated, then these assets may be valued more by debt holders. However, since we are focused on the effect of these investments on shareholders’ wealth, it is more likely that they will be valued less. Complicating this relationship is the evidence in Molina and Preve (2009) that firms’ extension of trade credit to their customers varies across phases of their distress. To measure bankruptcy risk, we use Altman’s revised Z-score (Altman, 1968) and Altman (2000). We expect that on balance the incremental value of a dollar invested in net operating capital to be increasing in the firm’s Z-score (i.e., the lower the bankruptcy risk the higher the valuation of the net investments). As an alternative, we follow Molina and Preve (2009) and use the Asquith, Gertner, and Scharfstein (1994) financial distress measure. Specifically, a firm is identified as being in financial distress if its coverage ratio (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization divided by interest expense) is less than one for two consecutive years or if it is less than 0.8 in any given year. WORKING CAPITAL MANAGEMENT AND SHAREHOLDERS’ WEALTH 1843 5.7 MACROECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL MARKET CONDITIONS Molina and Preve (2009), among others, suggest that macroeconomic and financial market conditions might influence investment in net operating working capital. An argument can be made that these factors also influence their valuation, but how much is unclear. The aggregate economic and financial market condition variables that we consider are: the LIBOR rate, the term spread, the credit spread, the annual change in real GDP, and the volatility of stock market returns. Their computation and rationale for inclusion are as follows. 5.8 LIBOR RATE We obtain the 3-month LIBOR rates and average them over a year to derive its value for a given year. We view the 3-month LIBOR rate as a reasonable measure of how the cost of short-term financing varies over time. To the extent that firms use short-term financing, then we should expect its sign to be negative as this measure should be correlated with the cost of capital. 5.9 TERM SPREAD We compute the term spread for a given year as the average of the monthly term spread, where the term spread is defined as the difference between the 10 year and 1 year constant maturity rates. Again, these data were obtained from the FRED database. We view this measure as capturing expectations about future inflation. Given the arguments in Preve and Sarria-Allende (2010), we should expect the coefficient on this variable to be negative. 13 Hadlock and Pierce (2010, p. 24). Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 adjusted (to 2004) book assets and age is the number of years the firm has been on Compustat with a nonmissing stock price. In calculating this index, “size is replaced with log($4.5 billion) and age with 37 years, if the actual values exceed these thresholds.”13 While we use their measure as our primary measure of the degree to which a firm is financially constrained, we also use a dummy variable for whether a firm has a bond rating or not as a robustness check. Faulkender and Wang (2006) also use this variable in their study as a measure of whether a firm is financially constrained or not. Further, Hadlock and Pierce (2010) provide evidence that whether a firm has a bond rating or not is a significant feature of unconstrained and constrained firms in their sample. 1844 R. KIESCHNICK ET AL. 5.10 CREDIT SPREAD 5.11 REAL GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT GROWTH RATE We compute the annual percentage change in real GDP using the data from the FRED database and use it as a proxy for real economic growth. If economic growth in the current period is important to the valuation of net operating working capital, then we would expect this variable to have a positive coefficient. 5.12 STOCK MARKET VOLATILITY To capture uncertainty about future economic conditions, we use the volatility of a stock index. Specifically, we compute the standard deviation of the equally weighted CRSP stock return index over the year. We expect the value of an additional investment in net operating working capital to decline in increasing economic uncertainty. To capture the effects of the above influences on the stockholder wealth effects of an additional investment in net operating working capital, we use the following model: rt RBt ¼ 0 þ 1 CðtÞ þ 2 Cðt 1Þ þ 3 EðtÞ þ 4 NNAðtÞ þ 5 RDðtÞ þ 6 IðtÞ þ 7 DðtÞ þ 8 LðtÞ þ 9 NFðtÞ þ 10 NWCtþ1 þ 11 NWCt þ "t , where 11 ¼ 1 F1 þ þ j Fj ð7Þ We report the results of estimating this equation in Table IV. To simplify and focus the presentation on the variables of interest, we only report the estimated coefficients for the interaction terms as they are the parameters of interest.14 14 We can provide the full regression results, including the own terms, upon request. Since the mean VIFs were all less than 8, multicollinearity is not an important concern. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 We use the spread between Moody’s Aaa and Baa Corporate Bond yields as a proxy for general credit risk. Using data from the FRED database, this spread is computed in a similar manner to how the term spread is computed. Ostensibly, if default risk becomes more of a concern, this spread should widen. Again, given the arguments in Preve and Sarria-Allende (2010), we should expect the coefficient of this variable to be negative. WORKING CAPITAL MANAGEMENT AND SHAREHOLDERS’ WEALTH 1845 Table IV. The effect of different influences on the incremental value of additional investments in net operating working to shareholders Model 2 Coefficient Coefficient Coefficient Coefficient DNWCt* NWCt 1 0.061 (0.19) 0.010 (0.01) 0.076 (0.20) 0.032 (0.49) 0.073 (0.21) 0.0619 (0.00) 0.905 (0.00) 0.380 (0.18) 0.156 (0.00) 0.044 (0.00) 1.450 (0.00) 0.274 (0.27) 0.060 (0.00) 0.999 (0.00) 0.288 (0.29) 0.152 (0.00) DNWCt*Past sales growth DNWCt*Future sales growth DNWCt*Lt DNWCt*Short-term debt DNWCt*Altman Z(t 1) 0.878 (0.00) 0.275 (0.18) 0.154 (0.00) DNWCt*financial distress DNWCt*SA Index 0.106 (0.00) 0.111 (0.00) 0.280 (0.00) 0.093 (0.00) DNWCt*Bond rating DNWCt*Libor DNWCt* term spread DNWCt*credit spread DNWCt*real GDP growth rate DNWCt*Stock mkt volatility F-statistic R2 0.004 (0.89) 0.033 (0.62) 0.091 (0.73) 0.002 (0.95) 0.238 (0.19) 121.11 (0.00) 0.21 0.012 (0.78) 0.008 (0.93) 0.303 (0.40) 0.011 (0.83) 0.217 (0.42) 95.05 (0.00) 0.22 0.093 (0.48) 0.130 (0.41) 0.417 (0.20) 0.069 (0.11) 0.111 (0.58) 98.58 (0.00) 0.21 0.407 (0.00) 0.002 (0.97) 0.001 (0.98) 0.346 (0.33) 0.009 (0.86) 0.257 (0.34) 96.49 (0.00) 0.22 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 Following Faulkender and Wang (2006), we regress the excess stock returns on changes in firm characteristics over the fiscal year. The base model is Model 2 of Table III. Added to it are: (i) NWC in the prior period; (ii) the firm’s sales growth over the past 3 years; (iii) the firm’s sales growth over the next 3 years; (iv) Lt is the market leverage; (v) short-term debt is the ratio of debt in current liabilities to total liabilities; (v) the firm’s Altman’s revised Z-score (Altman, 1968, 2000) for the prior year, or Asquith, Gertner, and Scharfstein (1994) financial distress measure; (vi) the SA index represents Hadlock and Pierce’s (2010) financial constraint index, or whether the firm has a bond rating; (vii) Libor represents the average 3 month Libor rate over the year; (viii) term spread is the average difference between the 10 year and 90 day Treasuries; (ix) credit spread is the average difference between AA and BB rated bonds; (x) real GDP growth rate is the inflation-adjusted GDP growth rate; (xi) Stock mkt volatility is the standard deviation of the CRSP equally weighted daily stock returns over the year. X represents 1 year changes (i.e., Xt – Xt 1). All variables based upon Compustat data were winsorized at the 1% and 99% level. Each regression model is estimated as a random effects model and uses Roger standard errors adjusted for clustering at the firm level. p-Values associated with the null hypothesis that the coefficient equals zero are reported within parentheses. 1846 R. KIESCHNICK ET AL. 15 Note, the evidence that other factors than sales growth influence the valuation of investments in net operating working capital implies that our earlier evidence on the valuation of investments in net operating working capital are not simply driven by sales growth. This is consistent with the fact that chief finance officers and security analysts use a firm’s cash conversion cycle or net trade cycle as a measure of a firm’s operating performance. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 The evidence in Table IV for the first two estimated regressions implies that the effects on shareholders’ wealth of changes in investment in net operating working capital are influenced by several factors. Specifically, we find that a firm’s expected sales growth, its use of long-term debt, its bankruptcy risk, and its financial constraints are important influences on the valuation effects of its additional investment in net operating working capital.15 However, we do not find the macroeconomic and financial market condition variables to be significant influences on the valuation of such investments. These later results may either reflect that a firm’s excess returns already factor in these influences, or that only firm-specific factors matter at the margin. Regardless, our evidence on the effect of a firm’s expected sales growth on the valuation of an additional investments in net operating working capital is consistent with the models (e.g., Sartoris and Hill, 1983; Kim and Chung, 1990, etc.) we profiled earlier. Turning to bankruptcy risk, we find that the higher the firm’s Altman’s Z-score, the more valuable its investments in net operating working capital are. In other words, the less likely the firm is to go bankrupt, the more valuable its investments in net operating working capital are perceived to be. To examine the role of financial distress on the value to shareholders of an additional investment in net operating working capital further, we substitute the Asquith, Gertner, and Scharfstein (1994) financial distress measure for the revised Altman Z-score and report the results in the third regression model reported in Table IV. These results make it clearer that when a firm is in financial distress, further investments in net operating working capital reduce shareholders’ wealth. These results are also consistent with the evidence that higher the firm’s debt load, the less valuable investments in net operating working capital are. We also find that the degree to which a firm faces financial constraints also influence the valuation of their investment in net operating working capital. Specifically, the results using the SA index suggest that the more financially constrained a firm is the more valuable its investments in net operating working capital are. Since these firms are smaller and younger firms, then it is reasonable for them to be building up their net operating working capital. WORKING CAPITAL MANAGEMENT AND SHAREHOLDERS’ WEALTH 1847 6. The Contribution of Different Elements of Net Operating Working Capital to Shareholders’ Wealth Consistent with the theoretical models, and industry studies that argue that trade credit, received or extended, along with inventories should be jointly considered because of their interdependencies, we have focused on the effects of investments in net operating working capital on shareholders’ wealth. This analysis, however, does not make clear the relative contribution of the different elements of net operating working capital to shareholders’ wealth and so we turn to such an analysis. Based on Equation (2), we should expect the value of incremental investments in accounts receivable to be positive and less than one since an incremental dollar in accounts receivable may not be paid, or maybe be paid much later. Based on Table III’s results for firm leverage, we should expect the value of incremental increases in the firm’s use of trade credit to be negative. However, this expectation must be tempered by the possibility that this type of financing may be substituted for more expensive forms of financing. Finally, we should expect the value of an additional dollar invested in inventories to be less than the additional dollar invested in Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 Whether this reflects the degree to which they face financial constraints versus the fact that they are younger and smaller companies is unclear. So, as a robustness check, we use whether or not they have access to public debt markets by having a bond rating. Such a measure, as noted earlier, has been used in other studies for this purpose. The results reported in Table IV suggest that an additional investments in net operating working capital are valued less in financially unconstrained firms and more in financially constrained firms. Consequently, this evidence suggests that the market does not view additional investments in net operating working capital as increasing shareholders’ wealth when the firm has lower cost access to financial markets. One can interpret this evidence as consistent with Jensen’s (1986) free cash flow argument and hence agency costs concerns. To summarize, our evidence suggests that further investments in net operating working capital are less valuable to shareholders when the firm has a high debt load and as a result faces bankruptcy, and more valuable to shareholders when it faces financial constraints and future sales growth. While these results are largely consistent with extant models, they also indicate that other factors, not considered by these models, are important influences on the relationship between investments in net operating working capital and firm value. 1848 R. KIESCHNICK ET AL. 16 It is important to recognize that these estimates represent the marginal valuation effects of these changes on net rather than gross cash flows. In other words, only a part of every incremental dollar goes to investors, another part goes to the factors of production including suppliers. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 accounts receivable because of the additional risk of not selling an item in inventory. How much, however, is unclear. To make their relative contributions or effects clearer, we now break down net operating capital into its components: accounts receivable, inventories, and accounts payable. We then create variables from these components that are comparable to our cash and marketable securities variables (i.e., scaled by the MVE) and substitute these variables for our net operating working capital variables in the Model 2 of Table III and report the results in Column 2 of Table V. The evidence in Column 2 of Table V implies that an unexpected increase of $1 in accounts receivables is more valuable than an unexpected increase in inventories ($0.64 versus $0.43) for a firm with average characteristics.16 These estimates are roughly consistent with the logic of Sartoris and Hill’s (1983) model because with accounts receivable, you have the issues of if and when the firm will get paid for an item that it has sold, whereas with inventories you have these issues and the additional issue of whether or not you will sell the item. Consequently, these estimates suggest why firms try so hard to minimize the costs of their supply chain. Interestingly, unlike the use of long-term debt, the use of trade credit does not significantly diminish shareholders’ wealth. Earlier we noted that both Danielson and Scott (2004) and Petersen and Rajan (1997) provide evidence that firms facing financial constraints are particularly dependent on the use of trade credit to finance their current operations. Consequently, this evidence and our earlier evidence on the effects of financial constraints on how the market views additional investments in net operating working capital, suggests that the market recognizes the dependence of financial constrained firms on the use of trade credit to finance their operations. While these estimates reveal something about the marginal value to shareholders of the average firm of unexpected changes in these working capital accounts, they hide the range of their values. To address this issue, we re-estimate the model reported in Column 2 of Table V for different quartiles using least absolute deviation or quantile regression analysis. Specifically, we estimate this model for the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile of the excess return distribution jointly and report the results in Columns 3–5 of Table V. The difference between the coefficients on any given variable and their corresponding coefficient in the mean regression model reveals significant WORKING CAPITAL MANAGEMENT AND SHAREHOLDERS’ WEALTH 1849 Table V. The effect of additional investments in the components of net operating working capital on shareholders’ wealth Controls Ct 1 Ct ARt 1 ARt INVt 1 INVt APt 1 APt F-statistic R2 Mean q25 q50 q75 – 0.6027 (0.00) 1.4461 (0.00) 0.2680 (0.00) 0.6372 (0.00) 0.1428 (0.00) 0.4327 (0.00) 0.1235 (0.00) 0.0496 (0.61) 183.23 (0.00) 0.20 – 0.124 (0.00) 0.604 (0.00) 0.190 (0.00) 0.364 (0.00) 0.102 (0.00) 0.322 (0.00) 0.0529 (0.00) 0.0255 (0.50) – 0.272 (0.00) 0.841 (0.00) 0.201 (0.00) 0.465 (0.00) 0.113 (0.00) 0.347 (0.00) 0.0546 (0.01) 0.0425 (0.40) – 0.641 (0.00) 1.340 (0.00) 0.269 (0.00) 0.573 (0.00) 0.113 (0.00) 0.365 (0.00) 0.234 (0.00) 0.235 (0.00) differences in how the market values unexpected changes in these working capital accounts. This impression is confirmed by two tests. An F-test of equality of the coefficients on cash, accounts receivable, inventories, and accounts payable between the 25th and 50th percentile is 62.09, which is significant at the 1% marginal significance level. Further, a F-test of equality of the coefficients on cash, accounts receivable, inventories, and accounts payable between the 50th and 75th percentile is 225.11, which is also significant at the 1% marginal significance level. Thus, these coefficients are very different for these segments of our sample. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 Following Faulkender and Wang (2006), the dependent variable is a firm’s excess stock return over the year. Ct is the cash plus marketable securities; ARt is the accounts receivable at time t; INVt is the inventories at time t; APt is the accounts payable at time t. Controls are the variables in Column 2 of Table III not reported below. All variables except Lt and excess stock returns are deflated by the lagged MVE, Mt 1. X represents 1 year changes (i.e., Xt – Xt 1). All variables based upon Compustat data were winsorized at the 1% and 99% level. The first regression model is estimated as a random effects model and uses Roger standard errors adjusted for clustering at the firm level. q25, q50, and q75 represent quantile regressions at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile, respectively, of the excess return distribution. p-Values associated with the null hypothesis that the coefficient equals zero are reported within parentheses. 1850 R. KIESCHNICK ET AL. 7. Summary and Conclusions Corporate financial executives routinely identify working capital management as very important performance of their firm. Such importance is reflected in both the fact that CFO magazine and other practitioner outlets conduct annual survey of such practices, and the fact that a substantial portion of most firms’ assets are tied up in net operating working capital. And yet there are no published studies, to date, of the relationship between working capital management and shareholders’ wealth. Consequently, we provide the first such examination for US corporations. We not only examine this relationship but also how various factors, including the key features of prior models of the relationship, influence the effect of an additional investment in net operating working capital. And finally, we also provide evidence on how different components of a firm’s net operating working capital influence shareholders’ value, and so provide evidence on which components appear to exercise the greater influence. Using data on US corporations from 1990 through 2006, we find significant evidence that an incremental dollar invested in net operating capital is worth less than an incremental dollar held in cash for the average firm, which is consistent with Autukaite and Molay’s (2011) evidence for French firms. Most importantly, our results suggest that the value of an additional dollar invested in the net operating working capital is diminishing as the prior levels of such investment increase. These patterns hold even when we condition on a firm’s industry characteristics. To better understand the determinants of these relationships, we find that the value of an additional dollar invested in net operating working is significantly influenced by future sales expectations, which is consistent with the models developed by Sartoris and Hill (1983) and Kim and Chung (1990). Also consistent with prior literature, we find that access to external capital, bankruptcy risk, and the firm’s debt load are also significant influences on Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 Generally speaking, as we move from the 25th to the 75th percentiles, unexpected changes in any of these working capital accounts are seen as more valuable to shareholders. However, these changes can be quite dramatic. For example, a build-up of accounts payable is associated with a reduction in shareholders’ wealth in the 25th percentile, whereas it is associated with an increase in shareholders’ wealth for firms in the 75th percentile. A deeper understanding of what drives these differences requires richer models of these relationships than we presently have and so we leave this as an area for future research. WORKING CAPITAL MANAGEMENT AND SHAREHOLDERS’ WEALTH 1851 References Altman, E. (1968) Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy, Journal of Finance 23, 189–209. Altman, E. (2000) Predicting financial distress of companies: Revisiting the z-score and zeta models. Working paper. Available at http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/ealtman/Zscores.pdf. Asquith, P., Gertner, R., and Scharfstein, D. (1994) Anatomy of financial distress: An examination of junk-bond issuers, Quarterly Journal of Economics 109, 625–658. Autukaite, R. and Molay, E. (2011) Cash holdings, working capital and firm value: Evidence from France. Working paper, SSRN. Beranek, W. (1967) Financial implications of lot-size inventory models, Management Science 13, B401–B408. Brigham, E. and Daves, P. (2007) Intermediate Financial Management, 9th edition, Thomson Learning, Mason, Ohio. Carpenter, R., Fazzari, S., and Petersen, B. (1998) Financing constraints and inventory investment: A comparative study with high-frequency panel data, Review of Economics and Statistics 80, 513–519. Corsten, D. and Gruen, T. (2004) Stock-outs cause walkouts, Harvard Business Review 82, 26–28. Daniel, K. and Titman, E. (1997) Evidence on the characteristics of cross sectional variation in stock returns, Journal of Finance 52, 1–33. Danielson, M. and Scott, J. (2004) Bank loan availability and trade credit demand, Financial Review 39, 579–600. Deloof, M. (2003) Does working capital management affect profitability of Belgian firms?, Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 30, 573–587. Dittmar, A. and Mahrt-Smith, J. (2007) Corporate governance and the value of cash holdings, Journal of Financial Economics 83, 599–634. Ehrhardt, M. and Brigham, E. (2009) Corporate Finance: A Focused Approach, 3rd edition, South-Western: Mason, Ohio. Fama, E. and French, K. (1998) Taxes, financing decisions, and firm value, Journal of Finance 53, 819–843. Faulkender, M. and Wang, R. (2006) Corporate financial policy and the value of cash, Journal of Finance 61, 1957–1990. Fazzari, S. and Petersen, B. (1993) Working capital and fixed investment: New evidence on financing constraints, RAND Journal of Economics 24, 328–342. Garcia-Teruel, P. and Martinez-Solano, P. (2007) Effects of working capital management on SME profitability, International Journal of Managerial Finance 3, 164–177. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 the value to shareholders of additional investments in net operating working capital. Of the different components of net operating working capital, additional investments in providing credit to one’s customers appears to have the greater effects on shareholders’ wealth for the average firm. While we make a substantial contribution to the literature by providing evidence on the importance of efficient working capital management to shareholders, our evidence also suggests that there is a need to extend prior models of its effects on firm value. 1852 R. KIESCHNICK ET AL. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1827/1582505 by University of Colombo user on 13 November 2023 Gitman, L. (1974) Estimating corporate liquidity requirements: A simplified approach, Financial Review 9, 79–88. Hadlock, C. and Pierce, J. (2010) New evidence on measuring financial constraints: Moving beyond the KZ index, The Review of Financial Studies 23, 1909–1940. Haley, C. and Higgins, R. (1973) Inventory policy and trade credit financing, Management Science 20, 464–471. Hill, M., Kelly, G., and Highfield, M. (2010) Net operating working capital behavior: A first look, Financial Management 39, 783–805. ITworld.com. (2002) Poor Capital Management Costs Industry Billions. http://www.itworld. com/Man/4215/020614capitalmgmt/pfindex.htm (accessed 14 June 2002). Jensen, M. (1986) Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers, American Economic Review 76, 323–329. Kim, Y. and Chung, K. (1990) An integrated evaluation of investment in inventory and credit: A cash flow approach, Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 17, 381–390. Lewellen, W., McConnell, J., and Scott, J. (1980) Capital market influences on trade credit practices, Journal of Financial Research 3, 105–114. Meltzer, A. (1960) Mercantile credit, monetary policy, and size of firms, Review of Economics and Statistics 42, 429–437. Molina, C. and Preve, L. (2009) Trade receivables policy of distressed firms and its effect on the costs of financial distress, Financial Management 38, 663–686. Petersen, M. and Rajan, R. (1997) Trade credit: Theories and evidence, Review of Financial Studies 10, 661–691. Preve, L. and Sarria-Allende, V. (2010) Working Capital Management, Financial Management Association: Survey and Synthesis Series, Oxford University Press. REL Consultancy. (2005) REL 2005 Working Capital Survey. Available at http://www. relconsult.com/CFO;jsessionid¼CA3EDDA21398FB627617D2345C115D07. Sartoris, W. and Hill, N. (1983) A generalized cash flow approach to short-term financial decisions, Journal of Finance 38, 349–360. Schiff, M. and Lieber, Z. (1974) A model for the integration of credit and inventory management, Journal of Finance 29, 133–140. Shin, H. and Soenen, L. (1998) Efficiency of working capital management and corporate profitability, Financial Practice and Education 8, 37–45. Soenen, L. (1993) Cash conversion cycle and corporate profitability, Journal of Cash Management 13, 53–58. Wadsworth, G. and Bryan, J. (1974) Applications of Probability and Random Variables, 2nd edition, McGraw-Hill: New York.