Uploaded by

Lidya Gergess

Stuttering Therapy for Adults: Identification & Modification

advertisement

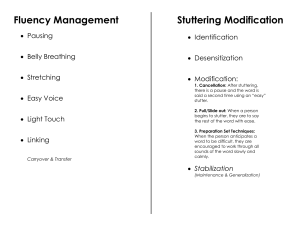

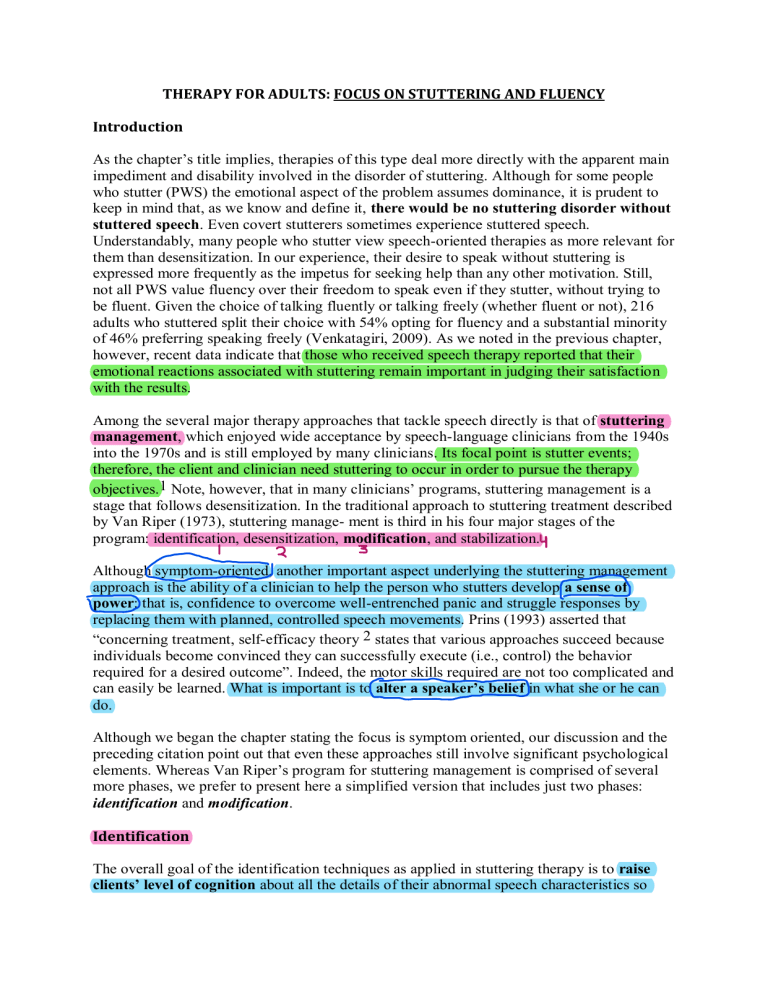

THERAPY FOR ADULTS: FOCUS ON STUTTERING AND FLUENCY Introduction As the chapter’s title implies, therapies of this type deal more directly with the apparent main impediment and disability involved in the disorder of stuttering. Although for some people who stutter (PWS) the emotional aspect of the problem assumes dominance, it is prudent to keep in mind that, as we know and define it, there would be no stuttering disorder without stuttered speech. Even covert stutterers sometimes experience stuttered speech. Understandably, many people who stutter view speech-oriented therapies as more relevant for them than desensitization. In our experience, their desire to speak without stuttering is expressed more frequently as the impetus for seeking help than any other motivation. Still, not all PWS value fluency over their freedom to speak even if they stutter, without trying to be fluent. Given the choice of talking fluently or talking freely (whether fluent or not), 216 adults who stuttered split their choice with 54% opting for fluency and a substantial minority of 46% preferring speaking freely (Venkatagiri, 2009). As we noted in the previous chapter, however, recent data indicate that those who received speech therapy reported that their emotional reactions associated with stuttering remain important in judging their satisfaction with the results. Among the several major therapy approaches that tackle speech directly is that of stuttering management, which enjoyed wide acceptance by speech-language clinicians from the 1940s into the 1970s and is still employed by many clinicians. Its focal point is stutter events; therefore, the client and clinician need stuttering to occur in order to pursue the therapy objectives.1 Note, however, that in many clinicians’ programs, stuttering management is a stage that follows desensitization. In the traditional approach to stuttering treatment described by Van Riper (1973), stuttering manage- ment is third in his four major stages of the program: identification, desensitization, modification, and stabilization. Although symptom-oriented, another important aspect underlying the stuttering management approach is the ability of a clinician to help the person who stutters develop a sense of power: that is, confidence to overcome well-entrenched panic and struggle responses by replacing them with planned, controlled speech movements. Prins (1993) asserted that “concerning treatment, self-efficacy theory 2 states that various approaches succeed because individuals become convinced they can successfully execute (i.e., control) the behavior required for a desired outcome”. Indeed, the motor skills required are not too complicated and can easily be learned. What is important is to alter a speaker’s belief in what she or he can do. Although we began the chapter stating the focus is symptom oriented, our discussion and the preceding citation point out that even these approaches still involve significant psychological elements. Whereas Van Riper’s program for stuttering management is comprised of several more phases, we prefer to present here a simplified version that includes just two phases: identification and modification. Identification The overall goal of the identification techniques as applied in stuttering therapy is to raise clients’ level of cognition about all the details of their abnormal speech characteristics so they can efficiently modify them. Familiarity with a problem is required for devising an effective means of resolving it (Van Riper, 1973). Interestingly, in the treatment of stuttering, identification has been known, at times, to have a significant impact on the overt stuttering all by itself. We have known several adults who showed a large reduction in the overt stuttering just going through it, without practicing any speech modification techniques. Van Riper, too, reported similar experiences. But we have also seen the opposite reaction, especially with a few mild cases, when the stuttering increased, or at least seemed to intensify for a while, as the client’s awareness of the stuttering details grew. Perhaps it is wise to advise clients of the possibility that stuttering may appear to intensify, so they do not become alarmed if it does. Iden- tification, though, is particularly important as groundwork for the subsequent direct management of overt stuttering through modification. Two essential phases in the identification program are awareness and analysis. Rationale What is the rationale for identification? How does a clinician explain it to clients? Several important reasons are elaborated here. These are worded as direct explanations to the client: Although you may be aware of the occurrence of stuttering, it is likely you are missing quite a few of them and are not aware of the specifics of how you stutter. Some PWS are surprised to hear so much stuttering in their recorded speech. People find it difficult to correct something that is unknown to them. Identification reveals the behaviors that should be targeted for modification and thereby also sets specific objectives for therapy. Identification requires you to take an active role in therapy early on. PWS are often under the impression that something will be done, or given to them, in therapy that will make their stuttering go away, similar to experiences they might have had with medical treatment of physical ailments. It is essential, therefore, that you understand that behavioral therapy depends almost solely on you doing the changing. The identification tasks that involve considerable verbal input from our clients describing and analyzing their stuttering contribute significantly to creating the desired mindset. The descriptive language you use in identification enhances your ability to take responsibility for your own stuttering. Williams (1957, p. 391) made the keen observation that people who stutter often relate to stuttering with animistic views. Such views are apparent when a person refers to “my stuttering” as if it is a living entity located somewhere in the body, acting independently, appearing on its own. Or alternatively, the person acts as if there is an outside force that makes him or her stutter. People who stutter often say, “words get stuck in my throat” as if words are small objects, not sounds resulting from muscle movement. You need to realize that stuttering occurs only when you act to tense your speech muscles, hold your breath, and so on. This can be achieved by analyzing stuttering with language that describes what you do during each instance of stuttering. For example, “I tensed my jaw” instead of “My jaw got stuck. Identification also contributes to desensitization. The more stuttering is discussed openly and objectively, the more you will experience that the associated emotional reactions are lessened. This concept is easy to understand because most people, children as well as adults, have experienced that merely by talking to a sympathetic listener about what has upset them, it makes them feel much better. Phase I: Awareness The objective of awareness is to increase a client’s accuracy in recognizing his or her stutter events. Van Riper (1973) referred to this process as detection. After discussing the objectives and rationale, the therapy takes on a hierarchical course, progressing from easier to more difficult tasks. As the client talks, detection can be indicated by saying “there” and pushing a clicker, a light switch, or other signals. Both the client and the clinician may count independently using a simpler counter, then compare and discuss differences. An example is shown in Table 12–1 of a reasonable sequence, including the following steps. It is self-evident that audiovisual feedback can be very useful. After the client has counted stuttering, a video may be watched for sake of comparisons. Typically, 95% accuracy is accepted as the criterion for success at each level in the hierarchy prior to progressing to the next level. Minor, brief stutter events should also be detected and counted. Although these often go unnoticed by the client, they could be important because tension builds up from mild blocks becoming more severe ones. Phase II: Analysis Having successfully met the first goal of awareness training, we move on to the second part of identi- fication, that of analysis, with the objective of becoming familiar with the details of the stutter events. Typically, the client is instructed to talk, pause after each stutter event, and describe what she or he was doing while stuttering — what were the various undesired and unnecessary component behaviors. Initially, you may encounter some difficulties on the part of the client to come up with more than a single description of his or her behavior during the stuttering that just occurred. Clients should be encouraged to provide additional details. In line with the rationale just outlined, emphasis is placed on using descriptive language — the “language of responsibility” — . Whether stuttering is perceived as something that happens or as something one does may be related to whether clients sense any control over their life more generally. A person’s locus of control is what one believes about what has an influence over life experiences. An external locus of control is the belief that outside forces have great influence on life events, whereas an internal locus of control is the belief that one’s self has a great influence on life events. A few scale measures of locus of control have been developed (e.g., Craig et al., 1984; Riley et al., 2004). Some research has shown relapse is more likely among those who exhibit an external locus of control (Andrews & Craig, 1988). In clinical practice, some programs compare pre- and posttreatment measures of locus of control to evaluate progress toward an increased internal locus (Guitar, 2014). The analysis of stutter events proceeds as the client speaks, including movements directly involved in the stutter events and those involved in the associated secondary characteristics. Here are a few steps: 1. As the client talks, she or he stops after a stuttered word and proceeds to describe (and keeps a list of) as many behaviors involved in the stutter event. For example: “I pressed my lips together on the p sound in the word “picture” then closed the right eye and tilted my head forward.” Because secondary characteristics often are easier to identify, more of these may be analyzed first. 2. The clinician may reintroduce the freezing technique by having the client hold on to the stuttering events for several seconds, focusing maximum attention on his or her behaviors, then proceeding with the verbal descriptions. 3. The client continues the analysis task in front of a mirror to facilitate identification of more subtle, or not so subtle, behaviors missed before. The clinician may provide additional refinement by pointing out still additional behaviors missed by the client. Audiovisual forms of feedback are particularly helpful for pinpointing the details. Thus, all the tense, unnecessary movements that constitute the stutter event are identified. 4. Finally, at times, the client may wish to recreate the stutter event just analyzed, observing again the movements involved and drawing conclusions as to what should be done to redirect the actions to result in unimpeded speech (e.g., start in easy on the vowel, keep the vocal folds open to permit airflow, bring the lips loosely together, etc.). This, in fact, is getting close to the stage of stuttering modification. Typically, not all steps in either the awareness or the analysis phases are covered in a single session. Time and repeated practice, literally hundreds of analyses, are needed not only for accurate awareness and analysis but also to impact the client’s attitude, understanding, and insight into the problem. It is possible for a person who stutters to demonstrate accurate stuttering analyses early on. Still, it is the extensive practice that brings about change in habituated beliefs and attitudes: taking the mystery out of stuttering and developing a strong realization that she or he is indeed doing the actions that constitute stuttering. Summary of Identification Exploration, detection, identification, awareness, and analysis of stuttering from an objective, non emotional perspective has the potential to be the foundation for speech change. Through this process the client and clinician discover what specific stuttering behaviors interfere with speech that should be modified as well as alter the client’s point of view of the nature of his or her problem. Decreased emotionality is a secondary important outcome. When attention is paid especially to proprioceptive dimensions of speech during exploration, the speaker can start gaining a sense of his or her own controls. Those controls are next employed to modify the person’s stutter events. An alternative method is the production of a whole new manner of fluent speech (known as fluency shaping) that will be presented at a later point. Modification The overall objective of modification is to develop the client’s skills for changing the habitual stuttering into easier, relaxed, less interrupted, more continuous speech movements. The basic tenet is that if a person has to stutter, the stuttering should at least be more acceptable to self and listeners. Such changes are achieved by self-monitoring and modifying speech movements just after, in the midst of, or in anticipation of stutter events. In short, the aim is easier disfluent speech, sometimes referred to as “fluent stuttering.” Prior desensitization training equips the client to respond more calmly and constructively to the stuttering block and change behaviors instead of reacting with a panic that makes the stuttering more severe. Following weeks of extensive analysis as described previously, the speaker can now quickly identify incorrect positions or gestures and transform each into more acceptable speech movements. The clinician continues to emphasize the theme of taking responsibility for stuttering behavior. The modification phase of stuttering management typically includes three procedural steps, all referenced in time with respect to the stutter event. Step I: Post-Block Modification The essence of the first procedure, referred to as post-block modification or cancellation, is changing the stuttering after it has occurred. In this procedure, - - - The client should complete the stuttered word and then pause. The clinician ensures that the client pauses only after the stuttered word is completed. Pausing too soon exploits an opportunity to avoid either the stuttering or the word being said. Avoidance of stuttering, however, is not the goal. It is to focus on what manner in which to say the word again. Based on behavioral theory, the pause is key because the time-out period interrupts the pattern of undesired reinforcement when stuttering is followed by further progress with communication. While pausing, the client quickly (1) analyzes the stuttering event, (2) reduces tension, and (3) plans necessary changes. In as much as the client has had ample practice analyzing stuttering during the previous identification phase, now he or she can do this quickly. Still, initially the pause may last at least several seconds, or as long as needed, in order to achieve the multiple tasks. Having paused, the client next reproduces the stuttered word but with the appropriate changes, such as light contact at the lips for the sound /p/ in “picture,” easy voice onset on vowels such as o in “ocean,” and/or a slower progression of movement. The reproduction may be exaggerated to enhance initial learning, by elongating or stretching out the word. Attention is focused on the oral sensation of speech movements and how these may guide adjustments. Sometimes the speaker may pantomime the word before speaking aloud. That is, the client makes a silent mouthing of how the word will be formed prior to speaking it again out loud. Sometimes the stuttered segment can be changed on reproduction using the bouncing technique. Bouncing is when a stuttered word or syllable is repeated several times with an easy, very relaxed production on each reiteration, such as in “pi- pi- pi- picture.” Because a major goal is to break the client’s stereotypic response, emphasizing variations in the new behaviors is important. Asking the client to restate the rationale for the cancellation technique is important to ensure its success. The client may be adequately motivated if the procedure is not found to be more embarrassing than stuttering itself, and if the gratification found by confronting and dealing with stuttering (the feeling of power) exceeds what is felt by avoiding it. Warning: Clinicians must monitor cancellations carefully because clients could tend to hurry through the procedure, pausing very briefly, with little analysis, slight reduction in tension, and minimal alteration in the movement. All too often, the process, especially the pause, seems inconvenient, even embarrassing to a client. It also interferes, although only temporarily, with interpersonal communication. Clients often prefer to bear with their old familiar stuttering than to engage in the pause and awkward new behaviors that deliberately call attention to the act of speaking. This is a time when clinician support is important as well as the time to review again the rationales for the procedure. Overall, it is a means for developing essential management skills as well a realization of being the master of one’s own speech. Clients do not just wait for the word to “come out”; they do something about it. Of course, once the client acquires the in-clinic modification skills for this phase, a generalization program is initiated, experimenting with the technique first in easy situations, such as initiating brief questions of their clinical personnel, expanding into various out-ofclinic situations. Step II: In-Block Modification Building on skills acquired with the post-block technique, the clinician introduces the second step — in-block modification, also referred to as pullouts. Assuming the client can now quickly identify and analyze the abnormal movement and tension on the stuttered word, the pause after it can now be eliminated so that changes in the speech are made earlier, right after stuttering occurs. - As soon as stuttering is detected, the client identifies and reduces the tension. Without pausing or stopping, the client “pulls out” of the block with relaxed, elongated, or easy repeated movements like those described for the post-block modification. For example, an instance of tense repetitions such as “a-a-a-a-ai” is altered “in progress” into an easily prolonged “ah→I.” The elimination of the conspicuous pause after the stuttered word (as in cancellation) greatly improves overall communication and naturally is preferred over the cumbersome post-block procedure. Important: When an in-block attempt fails, the client should immediately switch to a post-block modification as described earlier. Again, intensive practice provides an invaluable boost to a person’s feeling of power over his or her speech. Note: A common problem in stuttering modification therapy is clients’ tendency to speak more fluently after becoming comfortable with the clinical environment; hence, there may be few opportunities for practicing post-block and in-block modifications. The solution is simple: Instruct the client to stutter on purpose and then use the modification procedure. And, as in the earlier therapy stages, this too is to be completed with a gradual program of generalization. Step III: Pre-Block Modification The third step is the pre-block procedure that shifts modification to an even earlier time, prior to the occurrence of the stutter event. People who stutter frequently anticipate upcoming stutter events. Typically, some alterations in speech, including respiration, speaking rate, and tension, build up simultaneously with the anticipation. Van Riper (1971) referred to pre-block prepara- tions as preparatory sets. After spending many hours in therapy analyzing a large number of stutter events, the client can be expected to know much more about what malformed movements will eventually evolve into full-blown stutter events. Having this knowledge and the skill to generate easier speech, the client is now ready to alter those movements: - As a moment of stuttering is anticipated, but before difficulty ensues, he or she should analyze it and plan a modified approach. The client applies various techniques to approach the spoken word(s) differently, using easier, looser movements. For example, the client eases off tension in the jaw and lips, starts in with ease, and elongates the word just in time to mitigate the expected block. The overall impression might be that of a somewhat more gradual entry into the act of speaking. If the moment passes by too quickly, then either a pullout (in-block) or a cancellation (post-block) procedure is applied. Finally, here too a generalization program is to be followed. The detailed procedural aspects should not create the impression that therapy is, by and large, simply a technical matter. Above all, is the importance of being there for the client. The clinician must be a keen observer of the client’s feelings and reactions to shift readily from the role of a coach to a counselor. The counselor role requires understanding difficulties as they arise, easing frustrations, and offering encouragement when self-doubt and disappointment about progress are experienced. Also, the clinician-counselor redirects unrealistic expectations for therapy (such as insisting on perfect fluency or unwillingness to accept gradual progress) and is supportive with other personal issues that may surface. Summary of Modification Following intensive identification and analyses of stuttered speech events, therapy proceeds with three modification steps of post-block (cancellation), in-block (pullout), and pre-block (preparatory set) procedures — each requires changing the stuttering event at a different time in relation to its occurrence: after, during, and prior to. The purpose is to reduce the severity of stuttering rather than to strive for complete fluency. These modification activities aid speakers because they present alternatives to old painful habits and provide them with the sense of an internal locus of control, more specifically, the power to control their speech. Modification conveys the view that easy stuttering is a better choice than forcing the word out in a stuttered manner. Therapy programs along these lines have been very popular and variations of it have been pursued by a good number of clinicians, although they lack rigorous research support. During the recent decade, however, a few limited-in-scope, short duration studies have provided some support (Everared & Howell, 2018; D. Freud et. al., 2020; Tsiamtsiouris & Krieger, 2010). Fluency-Oriented Therapies There has been a long history of attempts to have people who stutter produce fluent speech, often using unusual means. The classic technique of rhythmic speech, paced by metronomic instruments, was practiced in Europe during the early part of the 19th century (see review by Wingate, 1976) or even earlier. Unlike the stuttering management approach that relies on the presence of stutter events to practice modification, a fluency management approach strives to afford people who stutter with completely fluent speech from the start. Rather than change only the stuttering event, the whole manner of speaking is altered. Little or no attention is given to preparing clients for how to handle stuttering should it occur, and usually little emphasis is placed on managing emotional reactions. The assumption is that when the person speaks fluently, negative emotionality, such as anxiety, will dissipate on its own. Fluency-oriented therapy emerged from two major sources. First was the observation of drastic amelioration of stuttering during externally imposed conditions (e.g., noise, speaking in chorus), suggesting that a common underlying production technique might be the key. A related assumption was that the abnormal biological system associated with stuttering could be overcome through careful retraining of basic speech gestures. Second, and a later one, was the application of operant conditioning principles to the treatment of stuttering that emphasized speech modification through reinforcement of behaviors that gradually approximated the target, that is, a behavioral shaping approach. There have been, however, some obstacles in pursuing this approach, especially the initial exaggerated speech patterns, such as slow speaking rate, gradual voice onset, articulatory imprecision, and so forth at the early stages of programs. The deliberate form of the fluent speech feels abnormal to the client; it does not sound like his or her own voice. Hence, success with this form of speech can be challenging. A client must be ready to embrace a new sense of self and keep practicing the new speech pattern despite strange, awkward feelings, knowing that more naturalsounding speech will be eventually reinstated as long as fluency is maintained. In the modern era, several fluency management techniques have incorporated instruments to facilitate, instate, and shape fluency. Other approaches, however, assign considerable responsibility to the clients’ active participation and intensive practice. Both of these types are reviewed here. The treatment of stuttering via a focus on a fluency-enhancing (or “managing”) approach represents both traditional and modern thinking. The main objective is to employ techniques, such as stretched speech, thereby quickly instating fluency in the person who stutters, even if, at least initially, the new speech is often characterized by distorted patterns. These patterns, however, are incompatible with stuttering. Once fluency is stabilized, speech is progressively shaped until it approximates normalcy, with the clinician ensuring that fluency is maintained throughout the various stages. At some point in the shaping process, generalization to the client’s everyday environment is initiated. Fluency-Focused Therapy Basics Typically, fluency-shaping programs begin by having the person who stutters speak in a novel but totally fluent manner. For example, speaking at a very slow rate, elongating (“stretching”) the vowels and/or intervals between consecutive syllables, or speaking to metronomic beats, may be used to render complete fluency. Because the remarkable change begins with rather unnatural speech patterns, clients may express pessimism or even resentment at being trained to talk in a way that would call as much attention as the stuttering. Therefore, early counseling is essential to point out that the exaggerated slow speech is temporary. It is only a means to learning correct speech gestures and other fluency skills, and speech will eventually approximate the normal manner. Ideally, the skills learned from a fluency-focused therapy should continue to support the smooth flow of speech after termination of treatment. Alas, rather typical to stuttering therapy for adults, transfer and maintenance of learning is frequently a challenge. A variety of programs have been developed in this treatment class. Clinicians, however, will discover that many commercially available kits will integrate some fluency-oriented techniques alongside traditional stuttering modification activities, such as identification and voluntary stuttering. Several skills that enhance fluent speech include the following: 1. slow speaking rate by “stretching” (elongating) the speech sounds, 2. smooth transitions between syllables (connecting across words within phrases), 3. easy contact of the articulator in consonant sounds, 4. gentle voice onset in vowel production, and 5. attention to intonation, stress, and breathing (additional airflow to carry the sounds). Each may be practiced first in isolation and then added to the overall pattern. Gradually, the slow, novel fluent speech pattern is shaped toward increased rate and naturalness. Typically such therapies have been administered in the format of an intensive (even residential) 2 to 3 week program with many practice hours per day. Hence, posttherapy follow-ups should be always considered if not planned, and, if needed, initiate an additional dose of therapy. Among the various versions of this therapeutic approach, an interesting one is the Campertown Program (O’Brian et al., 2003) that achieves the same objectives but with significantly less clinician-client contact. It saves time by allowing the client to imitate a videotaped model of the desired speech patterns. Next, there are three or so weekly sessions to be followed by reduced contact. (For more details see, https://www.uts.edu.au/researchand-teaching/our-research/australian-stuttering-re- search-centre/resources/camperdownprogram). The program has also been adapted to a telehealth platform (O’Brian et al., 2008), and more recently, Erickson and Serry (2016) offered an Internet-based, clinician-free version of the program. Findings of several small studies have indicated moderate success. Rhythmic Speech Normal speech is characterized by varying rhythm within and between utterances. When a person who stutters adopts a uniform rhythm by keeping equal intervals between syllables or words, the resultant fluency promises to be useful for treatment. Under such identical intervals between the spoken units, speech becomes rhythmic and fluency can be maintained even as the speaking rate increases. Keep in mind, however, that slow rhythmic speech has a very different quality from the slow-stretched speech (to be discussed later) that is often induced in fluency-oriented programs (described later). This is because with stretched speech, prosodic variations are possible and even encouraged; but it is not so during rhythmic speech. It always sounds robotic. In an extensive analysis, Wingate (1976) traced back to ancient times the realization that speaking in rhythm yields fluency. After the invention of metronomic devices in the early 1800s, rhythmic speech, with or without metronome pacing, has been employed by clinicians in various countries. Since then, however, the method has been characterized by erratic trends in popularity, but it has never attained widespread implementation by modern era clinicians. A rise in interest, for example, occurred in Europe near the middle of the last century. Dantzig (1940), in the Netherlands, advocated a syllable tapping program whereby each syllable was synchronized with a quiet tapping of the client’s preferred-hand fingers, progressing from the little finger toward the thumb. The therapy included three stages: (1) practice with deliberate finger tapping per each syllable, (2) minimize the tapping and obscure the view of the fingers, and (3) just imagine finger tapping. We believe that clinicians should be open to, and familiar with, the technique and apply it within an orderly program, such as the one described previously, when they encounter clients who show difficulties with other approaches or, for some reason, prefer this method. One rhythmic therapy program without the use of the metronome, referred to as syllable-timed speech, was carried on in the United Kingdom by Andrews et al. (1964). The clinical study used 35 clients ranging in age from 11 to 45 years, divided into four age subgroups. The 10day intensive program consisted of four stages: 1. Baseline. Case history and speech samples were recorded. Baseline measures of stuttering were taken. 2. TeachingSyllable-Timed(S.T.)Speech. Speechwasproducedsyllable-bysyllable,stressingeach syllable evenly in time to a regular, even rhythm. Practice began with simple sentences composed of one-syllable words. Clients progressed to reading prose and then to conversational speech. If stut- tering occurred, the phrase was immediately repeated, paying more attention to timing. By the end of the first 2 hr, most adults and adolescents were speaking fluently but at a slow rate of 80 syllables per minute. To become proficient, considerable practice was necessary, about 50 hr in individual and group therapy over 4 to 5 days. 3. Generalization. Over 10 days, every client retained S.T. speech in relaxed group practice sessions that focused on attitudes and concerns regarding stuttering. The group decided when they were ready for practice of S.T. speech outside the clinic, especially in previously difficult situations. Toward the end, clients spent more time accomplishing speaking tasks alone. An important assignment required clients to explain the changes in their speech to family, friends, and people in places of employment. This was done in order to facilitate clients’ commitment to speaking fluently upon returning to family or job. By the last day, speech approximated normalcy. 4. Follow-Up. For maintenance, a follow-up session for each group was held approximately once a week for 10 weeks. If stuttering occurred, clients were asked to continue talking in S.T. speech for the rest of the day and also practice at home. Next, tape-recorded formal interviews were held every 3 months across 1 year with an unfamiliar staff member. Speech samples were recorded so that speaking rate and stuttering frequency could be compared with respective base rates. Feedback was also obtained from clients’ families by means of questionnaires and stuttering severity ratings. Andrews et al. (1964) presented data showing that all four age subgroups exhibited substantial reduction (20%) in the frequency of stuttering as well as in its rated severity. The gains remained stable over 1 year after the termination of therapy. Substantial reduction (50%) in the frequency of stuttering, even without a portable device, was reported. More recently, a clinical trial showed syllable-timed speech (STS) to be a potentially useful treatment agent for the reduction of stuttering for school-age children. The present trial investigated a modified version of this program that incorporated parent verbal contingencies (Andrews et al., 2012). The technique is discussed again later in relation to the treatment of children. Slow Stretched Speech Several programs that emphasized slow, stretched speech were developed from the early 1960s on and gained significant acceptance. We review several of them here. Conversational Rate Control Therapy Curlee and Perkins (1969) were among the first to develop a prototype fluency management therapy program in which rate control leading to fluent speech was facilitated primarily by a delayed auditory feedback (DAF) device to help the client slow down. When the client talks into the microphone, the DAF instrument delivers sound back to the headset at a brief delay after speech is uttered. The longer the time delay, the more speech will be produced prior to the speaker’s hearing it. The delay induces slowing because the speaker is trying not to get ahead of the sound. The capability to incrementally increase or decrease the delay is an important element in the Curlee-Perkins rate control program. Overall, the program reflected a position that stuttering is a disorder of timing, characterized by lack of coordination of the various components of the speech system, namely, respiration, phonation, and articulation. Hence, therapy should advance compensatory skills that enable fluency. Initially, the client is prompted to engage in self-formulated conversation with fluency first estab- lished with a 250-ms delay. This results in an extremely slow speaking rate of about 30 words per minute, about 6 times slower than normal. Rate was gradually increased by adjusting the DAF to faster rates in 50-ms increments as long as the client meets fluency criteria. Also incrementally, both the volume of the DAF and use of the instrument are diminished until normal speech is achieved without DAF. The client is entrusted with responsibilities for all the program’s steps, including criteria for progress and correcting failures. Operant principles are important in the out-of-clinic generalization stage. The initial program in which slow speech was the sole procedure resulted in considerable improve- ment in the clinical setting as well as in everyday situations. Relapse, however, occurred in more than 50% of the clients. Later versions of the therapy regimen (Perkins, 1973a, 1973b) were expanded, adding continuous airflow throughout the utterance. While speaking slowly, the client is taught to maintain uninterrupted expiratory airflow on short utterances of three to eight syllables, ensuring sufficient air support. Because the slow fluent speech pattern tends to be monotonous, it is further supplemented by practice of normal prosody and emphasis on clear voice quality. Interestingly, Perkins (1973b, p. 299) also mentions the importance of what is called “psychotherapeutic discussion” that encourages clients to use positive language and discuss success throughout the program. Of course, every procedural step in this and any other approach involves a significant amount of practice in the clinical setting followed by much work to generalize the objective to various envi- ronments. To this end, the clinician charts out the therapy goals, teaches the techniques, presents a rationale, supervises the drills, provides feedback, and more. Clients need the clinician’s support and encouragement to move behaviors beyond the therapy room to the street, the workplace, and with friends, family, and strangers. Precision Fluency Shaping Devised by Webster (1980a, 1980b), precision fluency shaping has probably received more exposure than any other therapy of its kind. Theoretically, it is based on the assumption that motor abnormalities in articulatory, phonatory, and respiratory functions underlie stuttering, but that these can be overcome through careful retraining of the basic speech gestures. In the past it was presented as an intensive 12-day residential program. Therapy begins with immediately instating fluency by having a client speak while stretching the vowels at an extremely slow rate of one syllable per 2 s. Thus a two-syllable word would be prolonged over 4 s, slower than what was used in the programs described earlier. Instead of managing rate with DAF, the client is trained to mentally estimate and monitor the different speaking rates. Estimates are aided initially by tracking the seconds on a wristwatch. DAF is reserved for when/if stuttering occurs, and it rarely does. The objective of the therapy, however, is not just to achieve fluent speech but to have the client attain additional speech gestures that generate fluency. Thus, following extensive practice at an initially slow speaking rate, several articulatory and phonatory behaviors that become critical, in Webster’s opinion, are introduced. These are referred to as fluency targets. Perhaps the most notable after slow speech are gentle voice onset and light articulatory contact. Continuing with the program, and still using the initial rate of slow-stretched speech, treatment proceeds with the following steps: 1. Each vowel is practiced with a gentle voice onset. Acomputer-controlled biofeedback loop consisting of a microphone connected to an earpiece provides the speaker with an immediate awareness (audible beeping) concerning the acceptability of the slope of the gradual voice onset. Note: The instrument, however, is not essential. The clinician’s feedback and guidance can be very effective in helping the client to monitor the softness of the voice initiation. 2. Slow-easy syllables beginning with consonants are practiced in combination with gentle, gradual voice onsets on the initial sound and subsequent vowel. Consonant classes are addressed in the following order: a. voiced continuants (e.g., w, l, v, and z) are practiced, such as, W-olf; L-ike; V-ase; Z-oo b. voiceless fricatives (e.g., s, f) are practiced with lower intraoral air pressures in combination with gentle voice onsets, such as, S-un; F-our c. plosive consonants (e.g., b, t, k) are practiced with light articulatory contacts in combination with gentle voice onsets, such as, B-owl; T-ime; C-ar 3. Once these skills are mastered, all are simultaneously implemented in practice on single-syllable words uttered very slowly. 4. Next, the simultaneous fluency targets (slow rate, gentle voice, and light articulation) are incorpo- rated into longer words and then into phrases, all spoken very slowly. Systematic work on respiration, primarily the use of diaphragmatic breathing, is incorporated. For this purpose, another biofeedback device, a diaphragmatic breathing belt, is used. Again, the device is not essential. 5. As might be expected, the next phase in therapy is to gradually increase the speaking rate while maintaining all the fluency targets. Using a stepwise progression, the rate is raised from its initial slow-motion pace of one syllable per 2 s up to one syllable per second, then up to one word per second (60 words per minute), until finally a slow normal rate of 120 words per minute is reached. Although this pace is more than 10 times faster than the initial rate, it is still slower than the average normal speaking rate of 150 to 180 words per minute. 6. At this point, transfer and generalization begin, including telephone calls, visits to stores, and so on. In Webster’s clinic, participants spend many hours per day practicing speech. Practice time can be in the context of individual sessions with a clinician, group sessions, or even by themselves with computer feedback.Although the classic approach involves an intense practice schedule, the basic principles with many similar procedures and steps have been adopted by clinicians in a variety of settings with much lighter schedules, including the typical one or two weekly sessions. As stated earlier in this chapter, as well as in other chapters of this book, the clinical programs we cite were selected to represent the relevant principles, structure, and techniques for their approaches. Variations on therapy programs, both published and unpublished, have been devised and practiced by clinicians in the field. Clinical effectiveness studies have generally yielded positive results for this approach. A comprehensive analysis of 42 treatment studies (Andrews et al., 1980) found that therapies emphasizing prolonged speech, gentle onset, rhythm, and airflow were the most effective. Another study compared the efficiency of fluency-shaping training with 20 adult and adolescent clients who stuttered — half of whom received 16 hr of therapy within 4 days, and the other half, the same amount of therapy over 8 weeks. Both formats produced significant improvement in stuttering and other measures, and both were equivalent on all measures. Generalization of treatment effects was also observed for both groups (James et al., 1989). The question of whether fluency shaping results in posttreatment speech that is noticeably different was pursued in a study of 32 PWS taking part in a Dutch version of the precision fluency shaping program. Clients were tested immediately posttreatment and again at six months posttreatment. Listeners still rated their fluent speech as sounding different from that of control normally fluent speakers (NFS) (Franken et al., 1992). Behavioral Reinforcement We discussed stuttering within the framework of operant learning theory with an underlying assumption that stuttering is a behavioral response that may be modified by its consequences. Some support to this theory was provided by various experiments showing that stuttering can be diminished through several learning modes, for example, punishment, such as a 5-s timeout period (Martin & Haroldson, 1982), withdrawal of reinforcement (Lanyon & Barocas (1975), and withdrawal of aversive stimuli (Flanagan et al., 1958). Indeed, several therapeutic regimens have been developed contingent on stuttering events. Reinforcement tokens have been the most popular. In such a system, a client is given some tangible object to reward desired performance. Tokens, the reinforcement, can take any form but typically refer to small coinlike pieces resembling poker chips. Clients are given tokens only when they achieve the target. Tokens can be exchanged, like money, for prizes or privileges. The target behavior typically reinforced is fluent speech, but other behaviors may be rewarded too, for example, entering specified speaking situations from a sequential hierarchy (Andrews & Ingham, 1973). Research has shown that token reinforcement systems can be beneficial both by decreasing the time needed to reach the fluent speech target — greater efficiency — and by the amount of the reduction in stuttering attained — effectiveness (e.g., Andrews & Ingham, 1973). Some studies, however, suggested that token management may be unnecessary if a highly structured intervention system using other forms of reinforcement, such as praise or other verbal feedback, is employed (Howie & Woods, 1982). Relevant to this section on fluency-focused therapies, it is worth noting that reinforcement of fluent speech, rather than punishment of stuttering, has been the popular clinical implementation of operant conditioning principles. Generally, such approaches seek to gradually increase the length of fluently produced speech segments as well as the length of time during which fluency can be maintained. Clinicians interested in therapy that incorporates operant learning principles of scheduled rein- forcement may find Ryan’s (2001b) program of gradual increase in length and complexity of utterance (GILCU) to be a useful one. It includes two main stages, establishment and identification, combined with home practice. The establishment stage requires the client to follow 18 steps in each of three speaking modes: reading, monologue, or conversation. The 18-step series is repeated for each of these modes as appropriate. For example, a nonreader would not engage in the reading activity. Throughout the progres- sion of steps, both verbal and token reinforcements are administered. The clinician models and instructs the target speech pattern and evaluates the client’s response. Fluent productions are encouraged by the statement “Good” and a token; “Stop; speak fluently” is stated if the client stutters. Ten consecutive fluent responses is the criterion required to advance to the next step. The client is expected to discover his or her own strategies for speaking fluently, which typically involves some form of slowing speech rate. The two stages are outlined as follows: Stage I. The establishment program takes the client from practicing saying one word at a time ending with talking continuously for 5 min. Steps 1–6: The client progresses from speaking fluently one word at a time to six consecutive words at a time. Steps 7–10: The progression advances from speaking a single sentence fluently to saying four consecutive sentences at a time. Steps 11–18: The progression expands from speaking for 30 s fluently to 5 min fluently. Stage II. The identification stage is addressed after the first 18 steps are accomplished. That is, after instating fluency with one of the three activities (reading, monologue, or conversation), programs of identification (of stuttering), and home practice are initiated. This backward order of identification (after establishment) appears to serve as the means to develop the client’s self-monitoring and self-administration of the program targets. The adolescent or adult client is trained to recognize and count his or her own stuttered words. Step 1. The three-part identification training sequence begins with a 1-min speaking activity (i.e., reading, monologue, or conversation) during which the clinician identifies the client’s stuttering by stopping the client with the word “there” and then describing and imitating the stuttering while the client observes. Step 2. The clinician continues saying “there” when the client stutters, and the client overtly counts the moments during another 1-min speaking activity. To advance between steps, the client’s and clinician’s counts must agree within one stuttered word. Step 3. The clinician covertly counts stuttering moments while the client also counts covertly. Home practice, during which stuttering is identified and counted, is also included. As previously explained, the establishment stage continues with the other two modes of activities. Other programs have offered variations on the administration of behavioral contingencies. For example, James (1981) demonstrated that self-administered, response-contingent timeout periods could successfully reduce stuttering in a young adult man. Recall that time-out refers to having a speaker stop talking for a short time (several seconds) after she or he stutters. It is only mildly punishing. James found that fluency improvement was maintained at 6- and 12-month follow-up assessments after the treatment program. Approximately 15 years later, another published program trained clients in self-administered time-out for stuttering (Hewat et al., 2006). In this variant, clients made estimations — not only about whether they stuttered, but also about its severity and the passage of time. The improvement among their 22 clients varied, but more than half reduced stuttering by at least 50%. Dr. Betty McMicken, ASHA Fellow, provided the following case study. Adult Case Study Late remediation from stuttering is rather rare. This case study documents the reduction of stut- tering in an adult who exhibited long-term persistent stuttering and the subsequent maintenance of effective speech: fluent, natural sounding, spontaneous, and without external controls. Client HL was a 40-year-old male with about a 35-year history of moderate-severe stuttering. Having a long troubled history of drug abuse, as well as various encounters with the law, he lived in a special residential center undergoing a rehabilitation program while also working toward a high school diploma. HL reported that his speech had been a source of emotional pains and also resulted in educational failure, leading him at times to suicidal thoughts. Speech therapies during school were unsuccessful. Assessment HL’s stuttering baseline was obtained in four modes: conversation, monologue, telephone talk, and reading. On the average, stuttering occurred at a rate of 8 to 10 stuttered words per minute (SW/M) and was characterized mainly by part-word repetitions, sound prolongations, and facial secondary characteristics. Overall, stuttering was rated as moderate-to-severe. Interjudge reliability in counting stuttering was above 90%. His score on the Erickson S-24 scale was 20 (out of 24), indicating a high level of negative emotions associated with stuttering. Self-rating on a speech naturalness scale (1 = highly natural speech; 9 = highly unnatural speech) was 7 to 8. Treatment