The End of Empire in the Gulf: Trucial States to UAE

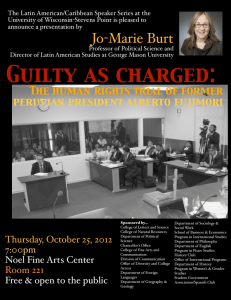

advertisement