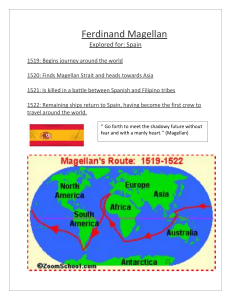

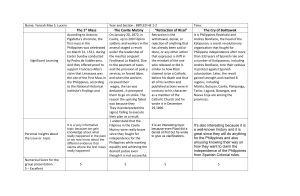

Magellan's Journey in the 15th and 16th centuries was a transformative period following the Renaissance and Reformation, shaping European society and culture while opening up new frontiers for exploration. Treaty of Tordesillas (1494): Background: 15th and 16th centuries witnessed significant changes post-Renaissance and Reformation, fueling European exploration due to the demand for Oriental products. Magellan's Contribution: Competition Between Spain and Portugal: Portugal's Prince Henry the Navigator established a navigational school to find a sea route to India around Africa. Bartholomew Diaz rounded the Cape of Storm (Cape of Good Hope). Vasco Da Gama found the riches of the East. Magellan studied the Spice Islands (Moluccas) and offered his services to King Charles I of Spain, partnering with cosmographer Rui de Faleiro. The Fleet of Magellan: Portuguese Exploration: Settled the conflict, drawing an imaginary line 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands. Lands east of the line belonged to Portugal (Africa, Asia, South America), while lands west belonged to Spain (Western part of the American continent). Consisted of 5 ships: Trinidad (flagship), Victoria (first to circumnavigate, under Juan Sebastian Elcano), Concepcion, San Antonio, and Santiago. Beginning of the Journey (September 20, 1519): Spanish Exploration: Christopher Columbus discovered the New World. Juan Ponce De Leon explored Florida. Vasco Nunez de Balboa was the first to see the Pacific Ocean. Antonio Pigafetta, a Venetian scholar and chronicler, recorded the world's first circumnavigation in his journal. Facing difficulties including a mutiny in Port San Julian, desertion of the ship San Antonio, and scarcity of supplies in the vast Pacific Ocean. Conflict Between Spain and Portugal: Columbus's expeditions caused a conflict between Spain and Portugal. Pope Alexander VI issued a Papal Bull, establishing an imaginary demarcation line in the Atlantic. Arrival in the Philippines (March 16, 1521): Reached the Island of Sails (due to beautiful sails). Encountered the Island of Thieves (Islas de Landrones) after small boats were stolen. Spotted the silhouette of Samar on March 17 and reached Homonhon on March 18. Account of Father Francisco Collins and Father Francisco Combes Easter Sunday Mass (March 31, 1521): Fr. Pedro de Valderama officiated the first mass on the shore of Limasawa, where they planted a cross and named the islands the Archipelago of Saint Lazarus. Baptism and Battle of Mactan (April 7, 1521): Magellan and Rajah Kolambu baptized Rajah Humabon, the King of Cebu, and his wife, who were given the names Carlos and Juana. A conflict between Lapu-Lapu and Magellan occurred on April 27, 1521. Magellan was killed, marking the first successful resistance against colonizers. Spanish Viewpoint of the Mutiny Return to Spain (1522): After three years, only the ship Victoria, with 18 survivors, including Juan Sebastian Elcano and Albo, returned to Spain. The other four ships met various fates: San Antonio fled back to Spain, Trinidad was captured by the Portuguese and wrecked in a storm, Santiago was lost at sea, and Concepcion was damaged and burned by the crew. Magellan's journey was a crucial chapter in global exploration, connecting continents, and contributing to European dominance in the Age of Exploration. Father Francisco Collins was familiar and precise with the accounts of Magellan's voyage and narrated Magellan's landing in Homonhon Island (Humunu as written in Pigafetta's Chronicle). Magellan's route: Collins mentioned Magellan first went to Limasaua, then to Butuan, and returned to Limasaua before sailing to Cebu. Father Francisco Combes supported Pigafetta's record and was one of the primary sources for Magellan's voyage. There was a law passed in Congress under Republic Act 2733 declaring Limasawa Island in the Province of Leyte as the place where the first mass in the Philippines was held. The event of 1872 was seen as a big conspiracy among educated leaders, mestizos, abogadillos (native lawyers), residents of Manila and Cavite, and the native clergy. It was believed that conspirators planned to liquidate high-ranking Spanish officers followed by the massacre of the friars. On January 20, 1872, a contingent attacked Spanish officers in Cavite, mistaking fireworks as a signal for the attack. Governor General Rafael Izquierdo ordered the reinforcement of Spanish forces in Cavite to suppress the revolt. Leaders were killed, and GOMBURZA (priests) were tried and condemned to die by strangling (Garote). Filipino Viewpoint of the Mutiny Dr. Trinidad Pardo de Tavera viewed the event as an ordinary mutiny by native Filipino soldiers and laborers in Cavite who were frustrated with the end of their privileges. Tavera believed that Governor Izquierdo was responsible for policies that contributed to discontent. The mutiny in Cavite involved dissatisfaction among workers affected by the abolition of privileges. The rebellion was suppressed when expected support from Manila did not arrive. Tavera argued that the Spanish friars and Gov. Izquierdo used the mutiny to maintain power in the Philippines. Accounts of the Cavite Mutiny The event was characterized by the Spanish as a conspiracy among educated leaders, mestizos, lawyers, and residents of Manila and Cavite, aiming to overthrow Spanish rule. The mutiny began with the mistaken belief that fireworks during a celebration in Sampaloc, Manila, were a signal for the attack. Governor General Izquierdo ordered the reinforcement of Spanish forces in Cavite to quell the revolt. Leaders of the plot were killed, and GOMBURZA (priests) were executed. The event ignited a sense of nationhood among Filipinos and contributed to the Philippine Revolution. Changes During Gov. Gen. Izquierdo's Rule Governor General Izquierdo prohibited the founding of a school of arts and trades, believing it was a cover for a political club. Privileges of workers in the Cavite arsenal were abolished, leading to dissatisfaction. The mutiny in Cavite erupted on January 20, 1872, led by Sergeant La Madrid. The event was used by the Spanish government and friars to maintain control. It ultimately led to the martyrdom of the three priests, GOMBURZA. Retraction of Jose Rizal Dr. Ricardo Pascual questioned the authenticity of Jose Rizal's retraction document, citing handwriting differences and punctuation. Fr. Vicente Balaguer was the only eyewitness to Rizal's confession, Mass, Communion, and prayers. The retraction document was a subject of controversy and debate. Taxation During the Spanish Period Tribute collection began immediately after the conquest of Legazpi and continued for over three centuries. Collectors of tribute included Cabeza de Barangay, Alcalde Mayor for the province, Mayor or Carreaidores (petty governors), and Alcalde or Gobernadorcillos (captains) for municipalities. These officials were responsible for collecting and remitting tribute to the treasury in Manila. Different Kinds of Taxes (During Spanish Colonial Period): Tributo (General Tax): Paid by Filipinos to Spain, amounted to 8 Reales. Required from males aged 18 to 50, as well as specific professions and town workers. Sanctorum Tax: Amounted to 3 Reales and was used for Christianization costs, church construction, and religious celebrations. Donativo Tax: Half Reales, required for the government's military campaigns. Caja de Comunidad Tax: 1 Real, collected for town expenses like road construction, bridge repair, and public building improvements. Servicio Personal (Polo y Servicios): Forced labor for able-bodied males aged 16-60 in construction work, including bridges, churches, and galleon ships. Lasted for 40 days. Gobernadorcillo, Cabeza de Barangay, and Principalia: Certain individuals were exempted from forced labor and fines. Taxes Imposed by the Spanish Government in the Philippines (1884): Royal Decree of March 6, 1884: Abolished the tribute and replaced it with the cedula tax. Also reduced the annual forced labor (polo) from 40 to 15 days. Different Versions of the Revolution: Pio Valenzuela's "Cry of Pugad Lawin": Claimed to have witnessed the event on August 26, 1896, although later accounts mentioned August 23, 1896. Santiago Alvarez's "Cry of Bahay Toro": Not an eyewitness, but associated with a different version. Gregoria de Jesus's First "Cry": She participated in the event near Caloocan on August 25, 1896. Katipunan General Guillermo Masangkay's "Cry of Balintawak": Witnessed the event on August 26, 1896, and was stationed on the path where the Spaniards were to pass. Soledad Borromeo Buehler: Associated with the Cry of Balintawak, based on Masangkay's account. First President of the Philippines: Emilio Aguinaldo: Recognized as the first Philippine president due to his election during the Tejeros Convention on March 22, 1897. Andres Bonifacio: Some argue that Bonifacio should be considered the first president because he served as the Supremo of the Katipunan revolutionary government from 1896 to 1897 and declared an armed revolution against Spain on August 24, 1896. This view suggests that the Katipunan government predated the Tejeros Convention