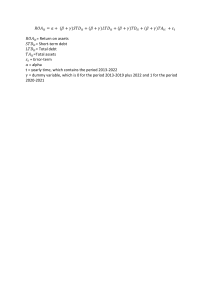

iew ed Title page Title: Navigating the “turquoise zone” of sustainable finance: An Exploration of the Emergence and Contribution of blue bonds pe er re v Author names and affiliations: Morag Torrance, School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, S Parks Rd, Oxford OX1 3QY, UK Felicia Liu, Department of Environment and Geography, University of York, York, YO10 5NG * Dariusz Wójcik, School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, S Parks Rd, Oxford OX1 3QY, UK; St Peter’s College, New Inn Hall St, Oxford OX1 2DL, UK *Corresponding author: Felicia.liu@york.ac.uk Acknowledgements Pr ep rin tn ot Dariusz Wójcik has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement number 681337). The article reflects only the authors’ views, and the ERC is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Keywords 2 Blue economy; sustainable finance; green bonds; marine conservation; biodiversity 3 Highlights ev ie we d 1 - Blues bonds emerged in recent years to finance marine conservation 5 - Issuers, investors, and use of proceeds are highly divergent 6 - Corporates, NGOs, and multilateral development banks hold different visions 7 - Concerns over transparency, governance, and impact generation remain 8 Abstract 9 In 2018, the Republic of Seychelles issued the world’s first blue bond as a ‘debt for nature swap’. ee rr 4 Hailed as an innovative solution to mobilise a blend of public and private capital to the conservation 11 of vulnerable marine ecosystems, other multilateral development banks, sovereigns, and private sector 12 actors followed suit to issue blue bonds. Despite its growing popularity, there is yet to be clear 13 consensus over what ‘blue’ entails and how ‘blueness’ should be governed. In this paper, we provide 14 a comprehensive analysis of the emergence and evolution of the blue bond market from an economic, 15 environmental, and geographical perspective, and ask whether blue debt instruments are effective in 16 promoting positive environmental outcomes in marine ecosystems and engaging new participants that 17 were previously excluded from the sustainable finance market, at the same time maintaining market 18 viability of the instrument. Our findings demonstrate varying degrees of success in achieving these 19 objectives. Unlike the green bond market, which is primarily dominated by issuers from Western 21 tn rin countries, more than half of blue bonds have been issued by Asian firms and small island sovereign states. Additionally, we identified two distinctive but overlapping groups of actors, led by conservation NGOs and investment banks, championing divergent definitions, structures, and Pr 22 ep 20 ot p 10 23 governance of this novel debt instrument. The former advocates for blue financing that exclusively 24 focuses on ocean conservation, whereas the latter seeks to expand the definition of ‘blue’ to This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 encompass a broader range of ocean economic activities. Consequently, blue bonds issued by the 26 latter group also enjoy better market returns and attract a wider array of private-sector investors. Our 27 research reveals that multilateral development banks play a mediating role between these two groups, 28 but the absence of standardised eligibility requirements and governance standards raises concerns 29 regarding ‘blue washing’. Path dependencies also mean that a lot of lenient but market-friendly 30 governance practices from the green bond market, such as voluntary reporting and self-labelling, are 31 transferred directly to blue bonds. Moreover, we raise questions over the legitimacy of wealthy 32 Western NGOs and private sector investors to wield significant influence over the management of 33 vulnerable marine ecosystems through brokering and investing in blue bonds. We argue the emergent 34 blue debt market is in a ‘turquoise’ space, where stakeholders with divergent interests and needs are 35 jostling to establish practices that best suit their needs. We caution that current processes have left 36 local communities out of the conversation. To this end, we question whether market development is 37 headed towards a direction where vulnerable ecologies and communities can reap the benefits the 38 emergence of blue bonds. 39 Introduction ot p ee rr ev ie we d 25 40 In the last decade, the financial sector has become increasingly aware of the environmental, social, 42 and governance (ESG) risks and impact of investments. Climate change has emerged to be a key 43 concern after the 2015 Paris Accord, with a growing number of high-profile financial institutions 44 taking measures to stocktake, reduce, and report their climate-risk exposure, while capturing 45 opportunities to invest in positive impact-generating assets (TCFD 2017). More recently, the threat of 46 biodiversity loss is coming to the fore of financial discourse (NGFS 2021; UNEP 2021). 48 rin Notwithstanding these developments, biodiversity conservation and nature recovery - especially conservation and recovery of marinescapes - receive markedly less attention (Bos et al. 2015; CBI 2021). In the last decade, only 1% of the ocean economy’s total value was invested in sustainable Pr 49 ep 47 tn 41 50 projects through philanthropy and bilateral public funding (WRI 2020). Given that oceans cover 71% This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 of the planet’s surface, and provide homes and livelihoods for nearly 3 billion people, while 52 generating an estimated economic value of USD1.5 trillion (World Bank, 2022), this lack of 53 investment flow towards marine conservation presents both a missed opportunity and an impediment 54 to sustainable development of ocean resources. we d 51 55 The emergence of blue debt instruments may provide a solution to this financing gap. The only 57 existing study, to our knowledge, has theorised blue bonds as a sub-set of the now familiar and 58 popular model of green bonds (Thompson 2022). However, this interpretation assumes the uniformity 59 of blue bonds and overlooks the divergent rationales, actors, and relational dynamics that drive the 60 development of this new category of sustainable debt. Understanding these nuances is crucial because 61 it shapes how a new sustainable finance instrument is constructed, which in turn determines the 62 (in)effectiveness of the instrument in delivering positive environmental impact at scale. To address 63 this gap in knowledge, the paper seeks to answer two questions. How and why has the new ‘blue debt’ 64 category emerged? What does it mean for raising and channelling capital to currently underfunded 65 ocean conservation and recovery, and for the broader sustainable debt universe? ot p ee rr ev ie 56 66 We address them by analysing the unique emergence and evolution of blue bonds and how this 68 process has shaped the structure and coverage of this financial instrument. In doing so, we contribute 69 to understanding the landscape of this emergent and potentially influential financial instrument for the 70 sustainable development of marinescapes, which bears immediate implications for equitable 71 development of small island nations, biodiversity recovery and development of nature-based 72 solutions. This adds to a rapidly growing literature on sustainable finance, providing important 73 insights in understanding how novel instruments and practices of sustainable finance emerge, and how 75 rin these processes of innovation shape the way in which sustainable investing (fails to) contribute to delivering timely, scalable, and measurable positive outcomes. Our paper also engages with critical debates on the financialisation of nature and nature recovery. Blue bonds are pushing the frontiers of Pr 76 ep 74 tn 67 77 sustainable finance by, for the first time, devising a financial instrument dedicated to the sustainable This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 development and recovery of the oceansphere. Our investigation of how the constellation of actors, 79 their motivations and tensions shape early market construction will provide an entry point for critical 80 reflection on how the encroaching influence of sustainable finance in public discourse impacts 81 societal interaction with the marinescape in the Anthropocene. we d 78 82 The remainder of the article is organised as follows. The subsequent section will review the literature 84 on sustainable finance, focussing on the emergence of different species of sustainable debt 85 instruments. After a brief methodological section, we present our findings and discuss the key themes 86 emerging from our analyses. The final section concludes. 87 Literature Review: Blue bonds in Context ee rr ev ie 83 88 Amidst the rapid growth of sustainable finance, sustainable debt has risen to prominence as a 90 pragmatic solution to ‘switching’ capital towards sustainable destinations (Castree and Christophers 91 2015). By 2021, the sustainable bond market surpassed the USD1 trillion mark with close to 17,000 92 issuances (CBI 2022). Much like regular debt, sustainable debt can be understood as an ‘IOU’ where 93 the borrower (otherwise known as an issuer) and the investor enter into an agreement of terms, rates, 94 and payments of the debt. Uniquely, the proceeds of the debt must be deployed towards assets with 95 environmental and social sustainability benefits, or to improve the sustainability performance of the 96 borrowing firm (Jones et al 2020; see Fig. 1 for a simple demonstration). To enhance the credibility of 97 the sustainability claims of the asset or performance target, the issuer may choose to hire a 98 sustainability specialist firm to verify the credentials. To this end, investors of sustainable debt expect 99 both financial returns, as well as positive sustainability outcomes on their investments. tn rin ep Pr 100 ot p 89 This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 we d ev ie ee rr 101 Figure 1 Typical structure of a sustainable debt that seeks to deliver both financial revenue and 103 positive sustainability outcomes (source: author’s own) ot p 102 104 Scholars from different disciplinary backgrounds have sought to explain the rising popularity of 106 sustainable debt. The business and finance literature focuses on whether sustainable debt provides 107 easier and cheaper capital for the borrower, (Baker et al. 2018; Hachenberg and Schiereck 2018; 108 Harrison et al 2020; Karpf and Mandel 2018), or an improvement of the eield for the investor 109 (Flammer 2021; Tang and Zhang 2020). While research is yet to reach a consensus that sustainable 110 debt improves the financial stakes for issuers or investors, it suggests that there are strong non- 111 financial business cases for issuers and investors alike to engage in the sustainable debt market as a 112 means to enhancing their reputation and stakeholder legitimacy (Maltais and Nykvist 2020). rin Scholars of financial sociology and geography have conducted qualitative deep-dives on how the Pr 114 ep 113 tn 105 115 sustainable debt market is constructed. A consensus emerged that the standardisation of the Green 116 Bond Principles (GBP) was key to the popularisation of sustainable debt and navigating the This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 conflicting logic of profits and sustainability (Hilbrandt and Grubbauer 2020; Monk and Perkins 118 2020; Perkins 2021). Published by the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA), an 119 internationally recognised association representing the fixed income investing market, the GBP has 120 been crucial in codifying and consolidating green bonds as a legitimate investment tool (Perkins 121 2021). By setting out four, voluntary principles-based components that issuers are expected to 122 disclose, namely (1) use of proceeds; (2) process for project evaluation and selection; (3) management 123 of proceeds and (4) reporting, GBP set a common language and expectations for sustainable debt. 124 This design is credited to a coalition of multilateral development banks, financial institutions and 125 sympathetic non-government organisations that constructed a ‘lenient zone’ of qualification that 126 requests just enough information from issuers to uphold the integrity of the product category, while 127 still being sufficiently flexible to maximise market growth (Perkins 2021). This coalition of 128 innovative champions reinforced the legitimacy of sustainable debt through repeated high-profile 129 issuances (Monk and Perkins 2020). Furthermore, by adopting an ecological modernisation framing 130 of sustainable debt as a ‘win-win’ solution to both finance and sustainability, sustainable bonds are 131 framed as a financially attractive and politically palatable ‘climate solution’ for public and private 132 sector stakeholders to engage with (García-Lamarca and Ullström 2022; Hilbrandt and Grubbauer 133 2020). ot p ee rr ev ie we d 117 tn 134 However, this market-friendly approach to sustainable debt governance has also led to significant 136 greenwashing concerns (Bloomberg 2019; Bracking 2015). Greenwashing comes in three distinct but 137 interrelated forms. First, sustainable debt has funded environmentally dubious projects. For example, 138 the Hong Kong International Airport issued a USD 1 billion green bond to fund the construction of a 139 third runway, which compromises the surrounding marine ecosystem inhabited by the endangered 141 Chinese white dolphins, in addition to enabling growth in carbon-intensive air traffic (Reclaim Finance 2022). Second, sustainable debt has been used as window dressing for firms that maintain a highly unsustainable business model. For example, Teekay Shuttle Tankers, a Canadian shipping firm Pr 142 ep 140 rin 135 143 specialising in oil and gas transportation, has attempted to issue a USD150 million green bond to fund 144 the building of new lower-carbon tankers (Environmental Finance 2019). Third, projects supported This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 by labelled sustainable debt instruments often lack additionality, with no evidence suggesting that the 146 same projects or assets would not have been pursued for purely financial reasons (Jones et al. 2020). we d 145 147 The jury is still out on whether sustainable debt market can deliver positive environmental or social 149 impacts. Having been conceptualised, designed, and governed by market actors, sustainable debt is 150 highly malleable to change as configurations of actors and tools shift. The emergence of ‘blue bonds’ 151 presents an opportunity to renegotiate and reconfigure the practices and boundaries of the sustainable 152 debt market. The ‘blue economy’ emerged as a distinct offshoot of the ‘green economy’, which seeks 153 to draw attention to marine natural capital assets as a new economic frontier (Schutter et al. 2021). 154 While investment in ocean protection and sustainable maritime projects have historically been 155 classified under ‘green’ finance, the bulk of green finance has focussed on decarbonising the built 156 environment and conserving terrestrial ecosystems. As a result, ocean conservation and maritime 157 decarbonisation concerns exist only at the margins of green finance discourses. The remainder of this 158 article will explore whether and how the differentiation of ‘blue’ from ‘green’ creates a distinctive 159 discourse that could draw policy attention and investment flow towards ocean scapes (McFarland 160 2021). That is, how has the sustainable finance community navigated this emergent ‘turquoise zone’? 161 Materials and Methods tn ot p ee rr ev ie 148 162 We took a multi-step, qualitative analytical approach to investigate the emergence of the blue bond 164 market. First, we conducted a desk-based analysis of reports published by multilateral development 165 banks, governments, financial institutions, and civil society organisations related to blue bonds and 166 the blue economy. We traced their relationship to identify the flow of knowledge, influence, and 168 capital to map out the constellations of actors involved in this emergent space. Building upon this, we consulted corporate reports, press releases and bond issuance databases, including Bloomberg, Reuters and Cbonds, as well as second-party reports such as the Climate Bonds Initiative to stocktake Pr 169 ep 167 rin 163 170 blue bond issuance so far. Specifically, we identified key information (whenever available) such as 171 the identity of issuers and investors, arrangers and managers, use of proceeds, and disclosure, This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 verification, and impact measurement methodology. By doing so, we can draw linkages between 173 unique narratives, constellation of actors, and practices that emerged together with this novel 174 instrument. To triangulate our desk-based analysis, a semi-structured interview with representatives 175 from an early blue bond issuer provided us with additional information about experiences and 176 processes that was not evident in the written documentation. ev ie 177 we d 172 Results 179 Rapid Expansion and Evolution 180 The blue bond market took root from a ‘debt for nature swap’ issued by the Republic of Seychelles in 181 2015. With the help of the World Bank and The Nature Conservancy, an international NGO, the swap 182 reduced the island nation’s outstanding sovereign debt and savings from the swap was redirected to 183 coastal ocean conservation (The Nature Conservancy, 2016). Three years later, the Republic of 184 Seychelles issued the world’s first blue bond, with proceeds used exclusively to support sustainable 185 marine and fisheries project (The Global Environmental Facility, 2018). Seychelles’ innovative 186 approach to channelling investment towards marine ecosystems inspired Scandinavian pension funds 187 and insurers to seek solutions to finance the protection of the Nordic-Baltic marine resources and 188 respond to demands from clients conscious of ocean pollution. Leveraging on existing wastewater 189 treatment facilities, the Nordic Investment Bank captured this opportunity by issuing its first blue 190 bond to finance the cleaning up of excessive eutrophication that has harmed ecosystem health and 191 threatened upstream sustainable urban development (NIB, 2019). 192 These early issuances set the stage for innovative, collaborative approaches to structuring and issuing ot p tn rin blue debt instruments. The scope of blue bonds has evolved and expanded as new issuances – including a blue loan borrowed in 2022 - bring new actors and objectives to the discourse. In total, we Pr 194 ep 193 ee rr 178 195 identified seventeen blue debts issued between 2018 and 2023, with at least four more under 196 construction at the time of publication (see Table 1 below). The total volume stands at USD 4.04 This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 billion, a fraction of the broader sustainable debt universe which surpassed USD 1 trillion in 2021. 198 Nevertheless, we observed four key features that would shape the development trajectory of blue debt, 199 namely the definitional contest of ‘blue’, the divergent economics of blue debt, the geographies of 200 investment flows, and impact measurement approaches. we d 197 202 Table 1. The evolution of the global blue debt market Year Issuer Name Size, Arranger Term coupon rate Area 3rd Party Investors of Targeted Monitoring Seychelles Public Procee d* Seychelles USD The World Nuveen, Seychelles Blue Bond 15m, Bank, Calvert private trust ot p 2019 Use Rep. of NIB 1 10 yrs, Standard Impact fund with 6.5% Chartered Capital, MPAs and Bank Prudential local DBS SEB Scan. inst. Nordic-Baltic SEK Blue Bond 1 2b, tn 2018 Known ee rr and ev ie 201 2 Baltic Sea investors annual NIB rin 5 yrs, World Bank Pr ep 2019 Cicero and impact report 0.38% WB SD Blue USD Morgan Private Bond 10m, Stanley placement 3 yrs, NYC with High - 2 Not WB Impact disclosed report Net Worth clients This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 USD Credit Private Economy 28m, Suisse placement Bond 5 yrs, NYC with High 2.73% Net Worth avg. clients 1 Not Bank of Bank of China USD Credit Van Eck China - Paris Blue Bond 500m, Agricole, Branch USD 3 yrs, 0.95% WB Impact we d WB SD Blue disclosed ev ie 2020 World Bank 2, 4 report China EY annual Vectors 95.68%, reporting BNP Green France Paribas, Bond ETF; Great Société UBS ETF Britain Générale (Lu) JP 4.32% ee rr 2019 Morgan Bank of Bank of China CNY Macau Blue Bond 3b, 2 Branch CNY yrs, USD ESG Diversified Bond ot p China - 3.15% NIB Nordic-Baltic SEK Danske Scan. inst. Blue Bond 2 1.5b, Bank, investors 5 yrs, Swedbank Qingdao tn 2020 Qingdao CNY Industrial Water Group Water Group 300m, Bank of Blue Bond 3 yrs, China 2 Baltic Sea Cicero and annual NIB impact report 3.63% - 3 Qingdao Lianhe province Equator Environment Impact Assessment Co. Pr ep 2020 rin 0.10% This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Seaspan Seaspan Blue USD BNP - 1 Corp. Transition 750m,8 Paribas maritime Bond yrs, China, routes 5.50% Societe Hong Kong Thai Union THB Bank of Thai Gov. Group Sust. -Linked 5b, Ayudhya, Pension Blue Finance 7 yrs, Mizuho Fund, Bond 1 2.47% Bank, Muang Mitsubishi Thai Life UFG Bank Insurance ADB ADB Blue AUD Citigroup Dai-chi Bond AUD 208, Global Life 15 yrs, Markets Insurance 1.80% ADB Blue rin 217, Credit Meiji 10 yrs, Agricole Yasuda 2.15% CIB Life Southeast Sustainalytic Asia s Asia and Cicero Pacific Insurance Industrial USD Industrial Van Eck Bank of Bank of China 450m, Bank of Vectors China Blue Bond 3 yrs, China Green 1.13% Hong Bond ETF Pr 2 s Company Industrial ep 2021 Sustainalytic NZD tn Bond NZD 1 ee rr Thai Union ot p 2021 ev ie Generale 2021 Global we d 2021 2, 4 China Sustainalytic s Kong This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Credit Agricole CIB 2021 “Debt for USD TNC and Investment ocean 364m, Credit Company, a conservation 19 yrs, Suisse subsidiary of swap” Blue - NYC TNC Bond Thai Union Thai Union THB Bank of Thai asset Group Sust. - Linked 6b, Ayudhya managers Blue Finance 5 and Bond 2 10 yrs, 2022 ot p 2.27% Alecta 5 BDO BDO Unibank USD BDO Unibank Blue Bond 100m, Capital Belize ev ie Belize Blue waters ee rr 2021 we d Branch, IFC 1 2 Public private trust fund with MPAs Southeast Sustainalytic Asia s Philippines IFC Guidelines 7 yrs, Bank of Bank of USD Bank of IFC, ADB, Qingdao Qingdao Blue 70m, Qingdao DEG and rin 2022 tn - Finance NA 1 Projects in IFC Qingdao Guidelines Barbados Public waters private trust Proparco Project Govt. of Debt for ocean USD Credit Nuveen Barbados conservation 73.3m, Suisse (80%) with the swap” Blue - NYC, TNC fund with TNC and the Bond and CIBC MPAs Pr ep 2022 5 IADB This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Caribbean Banco Banco USD Banco IFC, International International 79m, Internation Symbiotics Ecuador Blue Bond - al, Investment Blue Symbiotics s, LAGreen Guidelines Investment Rep. of Fiji Fiji Blue Bond 2023 USD Under 50m, constr. Govt. of Gabon ‘Debt USD Under 2023 Gabon with for Nature 700m constr. the TNC Swap’ Blue tn Bond ot p Exp. TMBThanac TMBThanacha 2023 hart Bank rt Bank Blue Thailand Bond - ep - - 1 5 Fiji Waters Fiji Sustainable Bond Framework Gabon - coastal waters IFC to 1 Thailand constr. commit up and Blue to USD Bond 50m Framework, S&P Green IFC Guidelines Exp. South Pacific ADB Blue 2023 Islands Bond Pacific Incubator Ocean Pr ICMA GBP Under rin Exp. Ecuador and IFC ee rr s Exp. 1 ev ie 2022 we d First - ADB - 1 South - 203 This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 * Use of Proceeds: 1. Blue Economy, 2. Restoring Water Health, 3. Desalination, 4. Offshore Wind, 205 5. Ocean Conservation 206 Definition of ‘Blue'? 207 All blue debt instruments are self-labelled by the issuers, and we observed a divergence of definitions. 208 One influential definition is offered by the World Bank, one of the first green bond issuers in the 209 world and a key actor supporting the popularisation of sustainable debt globally (Monk and Perkins 210 2020). It defines blue bonds as “debt instruments issued by governments, development banks or 211 others to raise capital from impact investors to finance marine and ocean-based projects that have 212 positive environmental, economic and climate benefits” (The World Bank, 2018b, online). This 213 definition places emphasis on governments and multilateral development banks as issuers of blue 214 debt, classifying it as a public financing tool. It restricts blue bonds to an ‘impact investing’ tool, 215 which is commonly understood amongst the financial community as an investment niche seeking to 216 “generate positive, measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return” (GIIN, 217 online), with some impact investors willing to accept concessions on financial returns (Brest and Born 218 2013, p.24). The Climate Bonds Initiative, a London-based NGO dedicated to the promotion and 219 governance of sustainable debt, offered a broader definition of the objective of blue bonds, where they 220 “finance sustainable land use and marine resources, and land and marine conservation” (CBI 2019, p. 221 16). This definition still requires alignment with marine sustainability goals, but it makes no 222 specification of the type of issuer or any requirements for impact creation. 223 More recently, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private sector-facing arm of the 224 World Bank, published guidelines providing more concrete recommendations on eligible projects, 225 focusing on those that contribute to UNSDG goals 6 ‘Clean Water and Sanitation’ and 14 ‘Life Below ev ie ee rr ot p tn rin Water’ (IFC, 2022). Notably, the IFC explicitly aligned its guidelines with the Green Bond Principles, suggesting that it targets a broad audience, including mainstream corporations and financial Pr 227 ep 226 we d 204 228 institutions that will be engaging in blue finance for market-rate profits. This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Notwithstanding the growing breadth in the process of standardisation of ‘blue finance’, we found an 230 even broader range of use of proceeds amongst the present universe of self-labelled blue bonds. Three 231 blue bonds – two dedicated towards offshore renewable energy and one committed towards seawater 232 desalination - do not fall under the definitional remit of the World Bank, the Climate Bonds Initiative, 233 or the International Finance Corporation. 234 Variety of Issuers, Debt Models, and Coupon Rates 235 Aligned with the divergent definitions of blue finance, we identified five key types of issuers in Fig. 2 236 below, namely multilateral development banks (n=5), sovereigns (n=3), hybrid (n=2 defined as state- 237 owned enterprises or banks that sit between sovereign and private sector) and private sector actors 238 (financial institutions n=4; corporates n=3;). ot p 240 241 ev ie ee rr 239 we d 229 Multilateral development bank, 5 rin tn Hybrid, 2 Pr ep Financial institution, 4 Sovereign, 3 Corporate, 3 242 This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Figure 2. Number of Issuers by Type 244 Blue debt issued by multilateral development banks and sovereigns tend to finance projects that are 245 generally beneficial for marine health, such as the restoration of water ecosystem health (n=5) and 246 protection of coastal waters (n=3). These projects deliver public goods, but they do not directly 247 generate revenue. For example, the Nordic Investment Bank blue bonds finance both the reduction of 248 nitrogen and phosphorus discharge into the Baltic Sea and the upgrading of drinking water systems to 249 prevent contamination due to climate change-induced downpours and flooding. Investors are not 250 repaid out of project revenues, but rather by the balance sheet of the Nordic Investment Bank, 251 contributed by its eight member countries. 252 We observed a loose relationship between types of issuer, use of proceeds, and coupon rates for the 13 253 blue debt issuances that disclosed financial information. All MDB-issued blue bonds follow a similar 254 model to the NIB bonds described above whereby public goods are funded and investors repaid via 255 balance sheets rather than revenue generated from economic activities or assets funded by the use of 256 proceeds. In contrast, blue debt issued by private sector actors (i.e., financial institutions and 257 corporations) tends to finance projects that directly generate revenue, for example, the development of 258 offshore wind (n=2), water desalination (n=1), green shipping (n=1), and improving the governance of 259 tuna supply chains (n=1). As a result, the bondholders are also repaid through project revenue. As 260 depicted in Fig. 3 below, the two lines represent the (1) coupon rate, which can be explained as the 261 annual interest payment received by a bondholder from the date of issuance until its maturity and (2) 262 the treasury bond rate, or risk-free rate, for the same duration issued by the government. The return 263 over the local treasury bond rate, referred to in finance as the spread over risk-free, increases from left 264 to right in this graph as visualised by the expanding vertical lines. 9 out of these 13 debt issuances 266 ev ie ee rr ot p tn rin offered a return, or spread over risk free, of less than 1% for the investor. The first 5 issuances, from Nordic-Baltic blue bond 2 through to the World Bank Sustainable Blue Bond offered spreads of 0.44% or less, implying a small return advantage over buying government bonds. Five of the bonds Pr 267 ep 265 we d 243 268 were issued by MDBs and it is no surprise that the returns are lower since they have AAA ratings: 269 they are funded by member countries’ tax contributions so can raise money cheaply and the risk to This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 investors is low. For example, the expected returns for the Nordic-Baltic blue bond 2 sits just above 271 the risk-free rate of the currency it was issued in: the Riksbank’s reference rate in January 2020 was 272 0.00, explaining the 0.10% coupon offered to investors as a small return for investing in it. we d 270 7 Annual blue bond coupon rate ev ie 273 Treasury rate matched to blue bond duration 6 5 Figure 3. The spread between the coupon rates and the treasury rates 276 There are two outliers in the graph: the Seaspan Blue Transition Bond and the Seychelles blue bond. SEASPAN USD Since the return calculation by investors is made based on a combination of long-term government bond yield, plus a risk assessment of the issuer’s activities and projects, the spread of 3.51% in the Pr 278 ep 275 277 SEYCHELLES USD (5 YR) TBH THAI UNION 2 THAI UNION 1 TBH NIB 1 SEK ADB AUD ot p B OF CHINA CNY IND. B. OF CHINA USD tn rin 274 NIB 2 SEK -1 ADB NZD 0 B OF CHINA USD 1 WB SDBB USD 2 % 3 QINGDAO WATER SOE CNY ee rr 4 Seychelles govt repay rate 279 Seaspan bond can be attributed to investors pricing in the business risk inherent in this enterprise. 280 Despite the higher business risk, investor appetite was apparent with this bond 5 times oversubscribed This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 and upsized from USD 500 to USD 750 million. It is worth noting that the favourable coupon rate of 282 sovereign blue bonds is enabled by a unique ‘debt swap’ structure to make them comparably 283 investable as other blue debt issued by multilateral development banks and corporates. Using the 284 Seychelles blue bond as an example, it was guaranteed partly by a USD 5 million World Bank 285 guarantee (IBRD) and supported by a further USD5 million loan from the Global Environmental 286 Facility (GEF) which help cover interest payments (The World Bank, 2018a). Once financial 287 guarantees and a credible governance structure were put in place, the Seychelles government’s 288 repayment rate was in effect subsidised and fell to 2.8% upon the condition that savings will be 289 funnelled towards ocean protection. The debt was subsequently underwritten with the guarantees in 290 place, reducing the risk of the investment, and investors were offered an attractive 6.5% return over 291 US treasury rates with the same duration, as evidenced in the graph. 292 Multilateral development banks and The Nature Conservancy (TNC) play a key role in brokering and 293 guaranteeing sovereign blue debts. Following the success of the 2018 Seychelles blue bond, a similar 294 model was deployed to support debt swaps for ocean conservation in Belize, Barbados, and Gabon 295 (Credit Suisse 2022; Maki 2021; Sguazzin and White 2023; The Nature Conservancy 2022). 296 Geographies of Issuers, Financial Intermediaries, and Investors 297 Blue bond issuers are spread geographically, with a high representation of issuers from less developed 298 and emerging economies (see Fig. 4 below). The former is represented exclusively by the low-income 299 small-island or coastal states issuing sovereign blue ‘debt swap’ bonds, all of them with assistance 300 provided by the TNC, multilateral development banks and bilateral grants. The latter is heavily 301 represented by Asian firms. Furthermore, China has not only issued the greatest number of blue debts, 302 but the country also represents more than half of issuance volume globally. ev ie ee rr ot p tn rin ep Pr 303 we d 281 This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Finland 394 we d Ecuador 79 Phillipines 402 ev ie Seychelles 15 China 2337 Thailand 334 ee rr USA 402.6 Barbados 73.25 304 Figure 4 Total blue debt by issuer country in USD millions 2018-2022 306 Asian corporates and financial institutions, particularly Chinese banks, are active in blue bond 307 issuance. The Bank of China issued a dual currency bond in 2021 (Credit Agricole, 2021a), while the 308 Industrial Bank of China, the largest commercial financial institution green bond issuer in the world, 309 issued its first blue bond, which was 5 times oversubscribed (Credit Agricole, 2021b). In June 2022 310 the Bank of Qingdao announced a new USD150 million blue loan to support up to 50 projects to 311 support the health of oceans and rivers within the Province of Qingdao (ADB, 2022; Proparco, 2022). 312 The facility signifies the first blue ‘loan’ in the world, and was jointly provided by the IFC, the ADB, 313 the German development bank DEG and the French development finance institution Proparco, and 314 adhered to the 2022 IFC Blue Guidelines. It sets a precedent for loan lending, which typically entails 315 private bilateral relationships between borrower and bank, in the blue financing space. Compared to tn rin bonds, which are typically publicly traded, loans offer smaller-scale firms and projects access to 'blue' labelled capital. Pr 317 ep 316 ot p 305 318 This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Outside of China, BDO Unibank in the Philippines issued the first blue bond in the Southeast Asia 320 region (BDO Unibank, 2022). The three non-financial corporate blue bond issuances so far were by 321 Asian firms. Seaspan, a containership company headquartered in Hong Kong announced the issuance 322 of USD 750 million in blue transition bonds in 2021 (Seaspan, 2021). In the same year, Thai Union 323 Seafood Group, a seafood production company listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand, issued a 324 THB 5 billion corporate sustainability linked blue bond with a follow-on THB 6 billion blue finance 325 corporate sustainability linked bond due to demand (Thai Union, 2021a and 2021b). It is worth noting 326 that these corporate blue bonds have adopted the ‘transition bond’ model where the proceeds are 327 deployed to improve the sustainability performance of the firms, including GHG emissions reduction, 328 improvement of sustainable fisheries practice (in the case of Thai Union), and upgrade of low-carbon 329 fleet and fuel use (in the case of Seaspan). Separately, Chinese state-owned enterprise Qingdao Water 330 Group earmarked its CNY 300 million blue bond for the expansion project of the Qingdao Baifa 331 desalination plant in the coastal province of Qingdao. Despite the strong Asian representation in the 332 current landscape, there are signs that private corporates and financial institutions in other regions are 333 taking up this novel instrument, with the Bank of Ecuador issuing Latin America’s first commercial 334 blue bond in 2022. ot p ee rr ev ie we d 319 335 Contrasting the strong representation of Asian corporations and coastal, small island nations as blue 337 debt issuers, the demography of financial intermediaries and investors of blue bonds is more 338 geographically diverse (see Table 2). Financial institutions located in Europe were involved in 339 arranging nine out of seventeen issued debts. The arranger refers to the intermediary that underwrites 340 the debt, structures the product, and disperses the investment product to investors. Three out of four 341 Chinese corporate issuances were arranged by French banks. Consequently, French investment banks, 343 rin such as Credit Agricole, Société Générale and BNP Paribas, arranged 25% of all global blue debts issued thus far (see Table 3). Simultaneously, the Paris branch of the Bank of China issued its USDdenominated blue bond. Pr 344 ep 342 tn 336 345 Table 2: Geography of issuers, arrangers, and investors This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Size of Head office Country of origin Geographic location of the issuer debt in country of the of the main financed assets/ USD arranger investor purposes (100% unless Seychelles USA China specified) 15 USA USA 28.6 USA USA 44 China Seychelles ev ie millions we d Country of Undisclosed Undisclosed Province of Qingdao, Barbados 73.3 USA/Switzerland/ Barbados Ecuador ee rr China 79 Ecuador/ Barbados USA/ Switzerland Ecuador ot p Switzerland/ USA Luxembourg 100 Philippines USA Philippines China 150 China USA/Germany/ China 152 Thailand/Japan rin Thailand tn Philippines France Thailand Southeast Asia 169 Denmark Sweden Baltic Sea Thailand 182 Thailand Thailand Southeast Asia Finland 225 Sweden Sweden Baltic Sea 302 USA/France Japan Asia and Pacific Pr ep Finland Philippines This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 364 Switzerland/USA Sweden Belize China 450 China/France USA China China 750 France Undisclosed Global maritime routes China 943 France USA China 95.68%, France and ev ie we d USA Great Britain 4.32% 346 Table 3: Lead arrangers on projects ee rr 347 Issuances Arranger Credit Agricole CIB BNP Paribas Société Générale tn Industrial Bank of China Bank of Ayudhya % of market share 3 11% 3 11% 2 7% 2 7% 2 7% 2 7% ot p Credit Suisse Group AG arranged We could not obtain publicly available, comprehensive data on the identity of investors in blue bonds. 349 This is unsurprising as investment destinations constitute commercially sensitive, proprietary 350 information. From the information available, investment in blue debt is widespread geographically, 351 with the IFC being a key investor in private sector financial institution issuances in China, the Philippines, and Ecuador. Financial institutions in Europe and the US have signalled sustained interest in blue financing. For example, Swedish investors made up 85% and 95% of the two Nordic-Baltic Pr 353 ep 352 rin 348 354 blue bonds issued in 2018 and 2019 respectively (NIB, 2020) and Swedish pension fund Alecta 355 invested USD75mn in the Belize blue ‘debt for nature’ bond after the US International Development This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Finance Corporation provided insurance (Fixsen, 2022). US-based impact investors Nuveen, 357 Prudential and Calvert Impact Capital invested in the first ever blue bond issued by the Seychelles 358 (The World Bank, 2018a) with Nuveen additionally buying 80% of Barbados’s debt for nature swap 359 blue bonds (Christiansen, 2023). Mainstream American asset managers have also initiated blue bond 360 investing, as exemplified by the inclusion of the Bank of China blue bonds in the VanEck Green Bond 361 Exchange Traded Funds (Cbonds, 2023b). Asian investors have likewise shown support for blue 362 bonds issued in the region. For example, Japanese life insurance firms purchased 100% of the Asian 363 Development Bank blue bond (ADB, 2021a), while the Thai government pension fund co-invested in 364 the corporate sustainability linked blue finance bond issued by Thai Union Seafood group (Thai 365 Union, 2021a). 366 Transparency and impact measurement 367 Akin to the lack of a standardised definition of what counts as blue, there is a lack of standardisation 368 over how the environmental benefits of blue debt can be governed. To this end, eight out of the 369 seventeen blue bonds followed the internationally recognised Green Bond Principles. 370 According to the Green Bond Principles, reliable and accurate disclosure of the selection of eligible 371 projects, management of proceeds, and impact is crucial in governing the ‘blue’ credentials of the debt 372 instruments accountable. Our results suggest that disclosure is at best patchy in reality. Fourteen out 373 of seventeen issuers disclosed quantitatively what the bond seeks to achieve environmentally. The 374 level of detail of disclosure varies. Some issuances come with timeframes for target achievement, 375 such as the protection of a specific percentage of coastal waters by a certain timeline (as in the case of 376 the debt for ocean conservation swaps issued by Seychelles, Belize and Barbados) or “Technical 377 specifications consistent with the Poseidon Principles, which is aligned with the International ev ie ee rr ot p tn rin Maritime Organization’s (IMO) goal of a least 50% reduction in total annual GHG emissions by 2050 compared to 2008” (Seaspan, 2021, p.13). Others offer objectives without a delivery timetable, for Pr 379 ep 378 we d 356 380 example: “The expected overall environmental benefits of eligible projects will include an 381 incremental sewage treatment capacity of 6,176,161 million m3/day and an increase of 2,987 MW This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 installed capacity for wind power project” (Bank of China 2020, p.2). Some targets are even more 383 opaque due to the wide variety of categories that are eligible for the use of proceeds. This is evident in 384 the Asian Development Bank blue bond where 9 themes are specified including for example: “Solid 385 waste management. Projects that reduce marine debris and/or associated impacts to marine life. 386 Projects must be within 50km of the coast or a river that drains to the ocean” (ADB, 2021a, p.1). 387 In addition to disclosure, obtaining independent verification provides further assurance of the quality 388 and ambition of the environmental benefits that the bond promises to deliver. Independent verification 389 providers abound, but it is worth noting that all multilateral development bank issuances (i.e. Nordic 390 Investment Bank and Asian Development Bank) use CICERO, a Norwegian sustainability verification 391 company that was acquired by S&P Global Ratings in December 2022. CICERO takes a unique 392 ‘shades of green’ approach that is often deemed rigorous, in that debts that fail to align and contribute 393 to a low carbon future will be called out in the ranking system. In contrast, corporate actors use a 394 range of independent verification providers, including Sustainalytics, Ernst and Young China, and 395 Lianhe Equator Environment Impact Assessment Co. However, it is notable that only NIB is 396 publishing the environmental impact of their blue bonds by publicly reporting the actual reductions 397 measured in nitrogen and phosphorus discharge into the Baltic (NIB, 2022). 398 Debt for ocean conservation swaps adopt a different governance structure to corporate blue bonds. In 399 addition to publicly disclosing their targets and commitments, debt swaps are governed by multilateral 400 governance bodies set up as a condition of the blue bond. For example, the marine conservation 401 progress of the Seychelles blue bond is overseen by the Seychelles’ Conservation and Climate 402 Adaptation Trust (SeyCCAT), while the Belize and Barbados blue bonds are governed by respective 403 trusts. These multilateral governance bodies are typically made up of the debt issuance country, as ev ie ee rr ot p tn rin well as representatives from the TNC, private sector actors, and civil society. Pr 405 ep 404 we d 382 This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Discussion: Navigating an Innovative ‘Turquoise Zone’ for Blue Bonds 407 At the beginning of this article, we posited that the emergence of blue bonds presents a new opportunity 408 to reimagine the purposes, practices, and governance of sustainable debt. Establishing a separate ‘blue’ 409 label could draw attention to ocean conservation and protection investment, which has often been 410 overlooked in the sustainable debt world where clean energy and green infrastructure investments 411 dominate (CBI 2022). Furthermore, establishing a fresh ‘blue’ label opens an opportunity to establish a 412 new set of eligibility criteria and governance practices to ensure blue bonds are delivering measurable, 413 ambitious benefits to marinescapes, thus differentiating blue bonds from the broader sustainable debt 414 universe, which has been plagued by concerns of greenwashing, owing to the lenient eligibility and 415 reporting requirements. ee rr ev ie we d 406 416 At the outset, the growing range of blue debt issuers and investors getting involved in the diverse debt 418 structures point to the blossoming of innovation and a promising trajectory of the concept of blue debt 419 gaining traction. Moreover, unlike the broader sustainable debt universe, where issuance and investment 420 emerged and remain concentrated in Europe (CBI 2022), we found a strong representation of blue debt 421 in Asia, as well as coastal, small island states, which also points to broadening engagement with 422 developing economies. tn ot p 417 423 Upon closer inspection, our analysis points to two distinctive but overlapping coalitions of stakeholders, 425 advocating divergent practices and visions for blue debt development. Borrowing from the concept of 426 financial ecologies, where the financial system is framed as a coalition of smaller constitutive ecologies 427 that emerge, endure, or fade away dependent on their uneven connectivities and influence (Lai 2016; 429 Langley and Leyshon 2017), we can conceptualise the current state of blue debt development as two ‘ecologies’ of financial knowledge and practices. The objectives, strategies, and early outcomes of these distinctive groupings of blue finance entrepreneurship deserve deeper scrutiny over whether they truly Pr 430 ep 428 rin 424 431 lead to equitable and effective outcomes of protecting marine ecosystems and community livelihoods 432 that rely heavily on them. This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 we d 433 The first ‘ecology’ is instigated by multilateral development banks and targets private sector issuers, 435 such as corporates and financial institutions. Led by the Nordic Investment Bank and the World Bank, 436 this coalition of actors seeks to deploy the novel ‘blue’ label to mobilise private capital to exclusively 437 support ocean clean up, protection, and conservation. They argue that the economy is heavily reliant on 438 a healthy marine ecosystem, therefore it makes business sense to use the ‘blue’ label to demarcate 439 investments dedicated to ocean protection and conservation. To this end, the World Bank, through its 440 private sector-facing arm, the IFC, introduced definitions and guidelines to align the definition of blue 441 finance with the UN Sustainable Development Goals 6 and 14, and to harmonise the governance of blue 442 bonds with the familiar and market-friendly Green Bond Principles. ee rr ev ie 434 443 The World Bank is an ‘incumbent’ actor in the green bond market, and its involvement in blue debt 445 development has led to the implementation of existing green bond governance modalities in the blue 446 debt world. Notably, the World Bank advocated for the adaptation of ‘use of proceeds’ model and 447 voluntary reporting of the environmental benefits prevalent in the green bond world. A key benefit of 448 adopting these approaches lie in user-friendliness and familiarity, but both academic and industrial 449 literature have pointed to their limitations in ensuring consistent, auditable disclosure to hold issuers 450 accountable for the delivery of positive environmental outcomes of (e.g. Bloomberg 2019; Perkins 451 2021). Our findings on the impact tracking and reporting of blue debt suggest that limitations of green 452 bonds have perpetuated into the blue bond space. tn rin 453 ot p 444 Furthermore, despite the World Bank’s effort to standardise the eligibility of ‘blue’ finance, our results 455 found a much broader range of use of proceeds emerging from corporate issuers, such as 456 457 decarbonisation of shipping fleets, offshore wind energy generation, and seawater desalination. Although these assets are physically located in marine spaces, they do not directly contribute to SDGs 6 and 14, and such projects have been financed through green bonds elsewhere. While ‘blue’ and ‘green’ Pr 458 ep 454 459 are not mutually exclusive, this debate on what constitutes ‘true’ blue and whether blue finance should This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 exclusively be dedicated towards ocean clean-up and marine conservation suggests that there is still a 461 lack of consensual definitions of blue finance. The negotiations of boundaries in this ‘turquoise’ spaces 462 open up for opportunistic private actor players to push the boundaries and adopt the blue finance label 463 on a more permissive range of projects to capitalise on this marketing opportunity. we d 460 464 Our analysis of the loose relationship between the use of proceeds and coupon rates offers some 466 explanation as to why some private sector issuers are motivated to expand the definitional boundaries 467 of blue bonds. Marine conservation projects such as restoration of water health and ocean conservation 468 tend not to directly generate revenue to repay its debtors. These projects are predominantly financed by 469 multilateral issuers who repay bondholders via their organisation’s balance sheet. In contrast, assets 470 such as offshore renewable energy and seawater desalination typically operate on a significant scale 471 with a steady revenue stream, thus making them relatively straightforward to be structured into an 472 attractive, ‘investable’ debt instrument. The fact they physically operate in the marinescape and are 473 already well-recognised by sustainable debt investors, allows corporates to capitalise on the novelty of 474 the ‘blue’ label without taking on additional risks. The ever-widening boundaries of what constitutes 475 ‘blue’ could lead to domination of lucrative or ‘investable’ marine assets and projects in the blue finance 476 space, thus defeating the initial purpose of establishing this new ‘blue’ debt label to attract private 477 capital towards marine conservation and protection. tn ot p ee rr ev ie 465 478 In comparison, the second ‘ecology’ appears a more explicit attempt to mobilise untapped private 480 capital towards marine conservation. Led by The Nature Conservancy, the US’s wealthiest conservation 481 charity, this coalition is made up of multilateral development banks, private sector financial institutions, 482 and coastal and small island states. The TNC targets small coastal and island states with rich marine 484 ecosystems that are also vulnerable to debt default, especially after the Covid-19 pandemic when tourism, a main source of GDP, dwindled. Nature debt swaps offer governments of these debt- Pr 485 ep 483 rin 479 486 vulnerable states a way to avoid sovereign debt default and reduce future borrowing costs, upon the condition that fiscal savings will be dedicated to marine conservation. This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 we d 487 TNC’s brokerage of nature debt swaps has been hailed for its sophisticated financial engineering to 489 deliver a ‘win-win’ for both ocean conservation and debt-burdened states. However, such praises tend 490 to overlook the uneven power dynamic and political implications of the TNC leveraging on a nation’s 491 debt to impose their conservation objectives and preferred conservation approaches upon a sovereign 492 state. An integral part of TNC’s debt swap condition is the creation of Marine Protected Areas, where 493 certain types of economic activities such as fishing are limited or prohibited to achieve conservation 494 targets. To ensure the conditions of the debt swap are honoured, the TNC sets up multilateral trusts or 495 boards set up by the TNC, where the government only makes up a minority representation. ev ie 488 ee rr 496 Though scarcely discussed (except in a blog post by Uneven Earth published in 2021), this structure in 498 essence infringes the sovereignty of these creditor states. Rather than implementing conservation targets 499 and strategies through the creditor state’s democratic procedures, the TNC used the risk of sovereign 500 default as leverage and sidestep any form of democratic procedures to implement their conservation 501 objectives. Furthermore, we did not find any publicly available evidence of consultation with local 502 leaders or communities over the setting up and subsequent governance of Marine Protected Areas, 503 despite history evidencing that similar protected areas have impinged the rights and livelihoods of fisher 504 people (Ban and Frid 2018; Silva and Lopes 2015). The fact that the debt swap was spearheaded by the 505 TNC means it is not subject to the United Nations’ best practices of obtaining free, informed, and prior 506 consent from local communities, which is crucial in avoiding neocolonial imposition when investing in 507 developing nations (Anderson 2011). This structure of conditional financing resembles the conditional 508 aid provided by Bretton Woods Institutions in the post-war era to less economically developed nations 509 to put in place neoliberal policy infrastructure and institutions, which often led to economically and 511 tn rin socially devastating outcomes. Only that, in this case, the conditions are set by a private, wealthy charity headquartered in the US, with very limited accountability to any governments, or indeed the people of Pr 512 ep 510 ot p 497 Seychelles, Belize, or Gabon. This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Finally, it is worth noting that private financial institutions underwriting and investing in blue debt 514 swaps are receiving a market-competitive coupon rate. This is possible because the debt has been 515 derisked by multilateral development banks. While this model has been hailed for its innovation, its 516 complexity and reliance on public finance derisking and guarantees raise the question of scalability. It 517 also suggests that blue debt has fallen short of incentivising the financial sector to fully internalise the 518 true value of marine ecosystems and the service they provide. 519 Conclusion 520 As blue debt becomes more widely adopted internationally, our study presents a timely investigation 521 of the development and evolution of this new category of sustainable finance instrument. Our research 522 suggests the current landscape of blue debt is rapidly evolving and highly fluid, and this fluidity 523 comes with epistemic, as well as environmental and social justice implications: scientifically complex 524 and politically laden decisions about what a sustainable future looks like are delegated to banks and 525 financial institutions. ev ie ee rr ot p 526 we d 513 Our paper identified tensions between divergent stakeholder priorities in the private sector, the 528 development sector, and the conservation sector. In turn, these tensions are manifested in the uneven 529 approaches to defining the boundaries of blue, in the profitability of different debt instruments, as well 530 as in the methodology of tracking and reporting of the environmental impact of the debt. The 531 opaqueness of blue bond governance poses the risk of ‘blue’ washing, and the asset class losing its 532 focus to mobilise and channel private capital towards the under-financed ocean conservation space. 533 Furthermore, the exclusion of local communities in the processes of determining the use and 534 management of proceeds of the debt instruments poses risks of maladaptation by neocolonial 536 rin environmental governance. Our intention to level these criticisms is not to undermine the innovation or necessity of this emergent Pr 537 ep 535 tn 527 538 market. Rather, we seek to identify any shortcomings and teething problems to open up the space for 539 productive discussions and improvement. Blue finance holds a unique potential in drawing investor This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 attention to ocean conservation and sustainable development of marine resources, and this is a space 541 that has traditionally been overlooked notwithstanding its importance to supporting livelihoods and 542 economies, as well as in delivering global climate, biodiversity, and sustainable development goals. 543 Our critiques bear broader lessons for emergent sustainable financial innovations seeking to reform 544 the relationship between capital, nature, and society, to channel investment towards under-invested 545 sectors, ecosystems, and geographies that hold the key to meeting global sustainable development 546 goals. ev ie we d 540 547 Going forward, more clearly defined eligibility boundaries and governance standards should be set 549 around blue finance to ensure traceability, accountability and equitable benefits sharing as capital is 550 (re)directed towards ocean protection and marine conservation purposes. Importantly, blue financing 551 must ensure local community consent, engagement and empowerment. Moreover, to avoid ‘blue 552 washing’, issuers should apply more rigorous methodologies to track and measure the environmental 553 impact, such as the deployment of (near)real-time spatial or ground-truthing techniques. ot p ee rr 548 554 Our research provided a comprehensive analysis of the early development of the blue bonds market. 556 Future research would benefit from an end-to-end deep-dive of a blue bond: from the bottom up of 557 measuring environmental improvements and community uplift (even after the blue bond matures), to 558 the governance of benefit distribution and allocation of proceeds, to the financial engineering, 559 brokerage, and trading. In order to more thoroughly understand the role finance can play in 560 contributing to nature recovery and other sustainability goals, it is crucial to understand how divergent 561 environmental and economic priorities held by different actors manifest throughout the cycle of 562 investment and impact generation. To do so would require a broad range of expertise including but 564 rin not exclusive to financial geography, (marine) ecology, and anthropology. To this end, we call for an interdisciplinary research agenda in sustainable finance to assess the outcome and critically evaluate the implications of financial capital shaping global terrestrial, marine and aquatic landscape as we Pr 565 ep 563 tn 555 566 navigate the unprecedented ecological challenges in the Anthropocene. 567 This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 we d 568 569 Pr ep rin tn ot p ee rr ev ie 570 This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 572 we d 571 References 573 ev ie 574 575 Asian Development Bank, (2021a). ADB Issues First Blue Bond for Ocean Investments. 576 September 10, 2021. https://www.adb.org/news/adb-issues-first-blue-bond-ocean- 577 investments ee rr 578 579 Asian Development Bank. (2022). Bank of Qingdao Blue Finance Project: Report and 580 Recommendation of the President. January 2022. Available at: 581 https://www.adb.org/projects/documents/prc-55246-001-rrp ot p 582 583 Baker, M., Bergstresser, D., Serafeim, G., & Wurgler, J. (2018). Financing the response to 584 climate change: The pricing and ownership of US green bonds (No. w25194). National 585 Bureau of Economic Research. tn 586 BDO Unibank. (2022). BDO Issues first Blue bond for US$100 Million. May 2022. 588 https://www.bdo.com.ph/news-and-articles/BDO-Unibank-Blue-Bond-USD-100-million- 589 first-private-sector-issuance-southeast-asia-IFC-marine-pollution-prevention-clear-water- 590 climate-goals-sustainability 592 Bloomberg. (2019). As green bonds boom so do greenwashing concerns. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-10-14/as-green-bonds-boom-so-do- Pr 593 ep 591 rin 587 594 greenwashing-worries-quicktake 595 This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Bos, M., Pressey, R. L., & Stoeckl, N. (2015). Marine conservation finance: The need for and 597 scope of an emerging field. Ocean & Coastal Management, 114, 116-128. 598 we d 596 Bracking, S. (2015). Performativity in the Green Economy: how far does climate finance 600 create a fictive economy?. Third World Quarterly, 36(12), 2337-2357. ev ie 599 601 602 Brest, P., & Born, K. (2013). When can impact investing create real impact. Stanford Social 603 Innovation Review, 11(4), 22-31. ee rr 604 605 Castree, N., & Christophers, B. (2015). Banking spatially on the future: Capital switching, 606 infrastructure, and the ecological fix. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 607 105(2), 378-386. ot p 608 609 Climate Bonds Initiative. (2019). Sustainable Debt Global State of the Market 2018. 610 Available at: https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/cbi_gbm_final_032019_web.pdf 611 Climate Bonds Initiative. (2022). Sustainable Debt Global State of the Market 2021. 613 Available at: https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/cbi_global_sotm_2021_02h_0.pdf rin 614 tn 612 Cbonds. (2023a). International Bonds: Industrial Bank (Hong Kong Branch), 1.125% 616 6nov2023, USD (Blue Bonds) XS2244313685. Accessed January 12, 2023. 617 https://cbonds.com/bonds/838181/ Pr 618 ep 615 This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Cbonds. (2023b). International Bonds: Bank of China (Paris Branch) , 0.95% 21sep2023, 620 USD (Blue Bonds) XS2231589784. Accessed January 12, 2023. 621 https://cbonds.com/bonds/789539/ 622 we d 619 Christiansen, S. (2023). Nuveen becomes anchor investor in new Barbados Blue Bond. 624 Citywire, March 7, 2023. https://citywire.com/selector/news/nuveen-becomes-anchor- 625 investor-in-new-barbados-blue-bond/a2410968 626 ev ie 623 Credit Agricole. (2021a). Bank of China issues Asia’s very first Blue Bonds. Accessed June 628 18, 2022. https://www.ca-cib.com/pressroom/news/bank-china-issues-asias-very-first-blue- 629 bonds#:~:text=Bank%20of%20China%20announced%20Asia's,issued%20by%20a%20com 630 mercial%20bank. ee rr 627 ot p 631 Credit Agricole. (2021b). Inaugural Blue Bond and COVID-19 Resilience Bond Priced by the 633 Industrial Bank of China. Accessed June 18, 2022. https://www.ca- 634 cib.com/pressroom/news/inaugural-blue-bond-and-covid-19-resilience-bond-priced-china- 635 industrial-bank 636 tn 632 Credit Suisse. (2022). Credit Suisse finances debt conversion for marine conservation in 638 Barbados. Press Release September 21, 2022. https://www.credit-suisse.com/about-us- 639 news/en/articles/media-releases/cs-finances-debt-conversion-for-marine-conservation-inbarbados-202209.html Pr 641 ep 640 rin 637 This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Environmental Finance. (2019). $150m green bond for oil tanker fleet in pipeline. Available 643 at: https://www.environmental-finance.com/content/news/$150m-green-bond-for-oil-tanker- 644 fleet-in-pipeline.html we d 642 645 International Finance Corporation. (2022). Guidelines Blue Finance. Guidance for Financing 647 the Blue Economy, building on the Green Bond Principles and the Green Loan Principles. 648 IFC, January 2022. ev ie 646 649 Fixsen, R. (2022). ‘Alecta says $75m blue bond investment meets sustainability, risk/return 651 needs’. Investments and Pensions Europe, January 27, 2022. 652 https://www.ipe.com/news/alecta-says-75m-blue-bond-investment-meets-sustainability- 653 risk/return-needs/10057641.article ot p 654 ee rr 650 655 656 Flammer, C. (2021). Corporate green bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 142(2), 499- 657 516 tn 658 García-Lamarca, M., & Ullström, S. (2022). “Everyone wants this market to grow”: The 660 affective post-politics of municipal green bonds. Environment and Planning E: Nature and 661 Space, 5(1), 207-224 663 664 GIIN. (Online). What you need to know about impact investing. Available at: https://thegiin.org/impact-investing/ Pr 665 ep 662 rin 659 This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Hachenberg, B., & Schiereck, D. (2018). Are green bonds priced differently from 667 conventional bonds?. Journal of Asset Management, 19(6), 371-383. 668 we d 666 Harrison, C., Partridge, C., & Tripathy, A. (2020). What's in a Greenium: An Analysis of 670 Pricing Methodologies and Discourse in the Green Bond Market. Harrison, Caroline, 671 Partridge, Candace and Aneil Tripathy. ev ie 669 672 Hilbrandt, H., & Grubbauer, M. (2020). Standards and SSOs in the contested widening and 674 deepening of financial markets: The arrival of Green Municipal Bonds in Mexico City. 675 Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(7), 1415-1433 ee rr 673 676 International Finance Corporation. (2022). Guidelines for Blue Finance. Washington,DC: 678 IFC. ot p 677 679 680 Jones, R., Baker, T., Huet, K., Murphy, L., & Lewis, N. (2020). Treating ecological deficit 681 with debt: The practical and political concerns with green bonds. Geoforum, 114, 49-58. tn 682 Karpf, A., & Mandel, A. (2018). The changing value of the ‘green’label on the US municipal 684 bond market. Nature Climate Change, 8(2), 161-165. 686 687 688 Published November 5, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-11-05/belizecures-553-million-default-with-a-plan-to-save-its-ocean?leadSource=uverify%20wall Pr 689 Maki, S. (2021). Belize Cures $553 Million Default With a Plan to Save Its Oceans. ep 685 rin 683 This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Maltais, A., & Nykvist, B. (2020). Understanding the role of green bonds in advancing 691 sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 1-20. 692 we d 690 McFarland, B. J. (2021). Blue bonds and seascape bonds. In Conservation of Tropical Coral 694 Reefs (pp. 621-648). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. ev ie 693 695 Monk, A., & Perkins, R. (2020). What explains the emergence and diffusion of green bonds?. 697 Energy Policy, 145, 111641. 698 ee rr 696 NGFS. (2021). Biodiversity and financial stability: exploring the case for action. NGFS 700 Occasional Paper. Available at: 701 https://www.ngfs.net/sites/default/files/medias/documents/biodiversity_and_financial_stabilit 702 y_exploring_the_case_for_action.pdf ot p 699 703 704 Nordic Investment Bank. (2019). NIB issues first Nordic Baltic Blue Bond. January 24, 2019. 705 https://www.nib.int/releases/nib-issues-first-nordic-baltic-blue-bond tn 706 Nordic Investment Bank. (2020). NIB launches five-year SEK 1.5 billion Nordic Baltic Blue 708 Bond. October 7, 2020. https://www.nib.int/releases/nib-launches-five-year-sek-1-5-billion- 709 nordic-baltic-blue-bond 711 712 Nordic Investment Bank. (2022). Our impact report 2021 is out. March 16, 2022. https://www.nib.int/releases/our-impact-report-2021-is-out Pr 713 ep 710 rin 707 This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Perkins, R. (2021). Governing for growth: Standards, emergent markets, and the lenient zone 715 of qualification for green bonds. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 111(7), 716 2044-2061. we d 714 717 Proparco. (2022). Supporting Ocean-Friendly Solutions in China. New Blue Loan to Help 719 Bank of Qingdao Pilot Blue Finance, Supporting China’s Climate Goals. June 24, 2022. 720 https://www.proparco.fr/en/actualites/new-blue-loan-help-bank-qingdao-pilot-blue-finance- 721 supporting-chinas-climate-goals ee rr 722 ev ie 718 723 Reclaim Finance. (2022). High-flying greenwashing around a new green bond for Hong 724 Kong Airport. Available at: https://reclaimfinance.org/site/en/2022/01/04/high-flying- 725 greenwashing-around-a-new-green-bond/ ot p 726 727 Seaspan. (2021). Seaspan Completes Significantly Upsized $750 Million Offering of Blue 728 Transition Bonds. July 14, 2021. https://www.seaspancorp.com/press_release/seaspan- 729 completes-significantly-upsized-750-million-offering-of-blue-transition-bonds/ tn 730 Schutter, M. S., Hicks, C. C., Phelps, J., & Waterton, C. (2021). The blue economy as a 732 boundary object for hegemony across scales. Marine Policy, 132, 104673. 734 735 736 Conservation. Published October 21. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-1021/gabon-is-in-talks-to-fund-marine-conservation-through-debtswap?leadSource=uverify%20wall Pr 737 Sguazzin, A. & N. White. (2022). Gabon Plans $700million Debt Swap to Fund Marine ep 733 rin 731 738 This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 Tang, D. Y., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Do shareholders benefit from green bonds?. Journal of 740 Corporate Finance, 61, 101427. we d 739 741 Taskforce for Climate-Related Financial Disclosures. (2017). Recommendations of the 743 Taskforce for Climate-Related Financial Disclosures. Final Report. Available at: 744 https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2021/10/FINAL-2017-TCFD-Report.pdf ev ie 742 745 Thai Union. (2021a). Thai Union Launches Thailand’s First Sustainability-Linked Bond. July 747 21, 2021. https://www.thaiunion.com/en/newsroom/press-release/1397/thai-union-launches- 748 thailands-first-sustainability-linked-bond ee rr 746 749 Thai Union. (2021b). Thai Union Successfully Launches New THB6 Billion Sustainability- 751 Linked Bond in Thailand. November 11, 2021. 752 https://www.thaiunion.com/en/newsroom/press-release/1483/thai-union-successfully- 753 launches-new-thb-6-billion-sustainability-linked-bond-in-thailand ot p 750 754 The Global Environmental Facility. (2018). Seychelles Launches World’s First Sovereign 756 Blue Bond. October 29, 2018. https://www.thegef.org/newsroom/press-releases/seychelles- 757 launches-worlds-first-sovereign-blue-bond 760 761 The Nature Conservancy. (2016). Rising Tides: Debt-for-Nature Swaps let Impact Investors Finance Climate Resilience. June 17, 2016. https://www.nature.org/en-us/what-we-do/ourinsights/perspectives/rising-tides-debt-for-nature-swaps-finance-climate-resilience/ Pr 762 rin 759 ep 758 tn 755 This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 The Nature Conservancy. (2021). Blue Bonds: An Audacious Plan to Save the World’s 764 Ocean. Last updated March 4, 2021. https://www.nature.org/en-us/what-we-do/our- 765 insights/perspectives/an-audacious-plan-to-save-the-worlds-oceans/ 766 we d 763 The Nature Conservancy. (2022). Case Study: Blue Debt Conversion for Marine 768 Conservation. Accessed June 18, 2022. 769 https://www.nature.org/content/dam/tnc/nature/en/documents/TNC-Belize-Debt-Conversion- 770 Case-Study.pdf ee rr 771 ev ie 767 772 The World Bank, (2018a). Seychelles Achieves World First with Sovereign Blue Bond. 773 October 29, 2018. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2018/10/29/seychelles- 774 achieves-world-first-with-sovereign-blue-bond ot p 775 776 The World Bank. (2018b). Sovereign Blue Bond Issuance: Frequently Asked Questions. 777 October 29, 2018. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2018/10/29/sovereign-blue- 778 bond-issuance-frequently-asked-questions tn 779 The World Bank. (2022). Blue Economy. Last accessed June 18, 2022. Available at: 781 https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/oceans-fisheries-and-coastal- 782 economies#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20OECD%2C%20oceans%20contribute%20% 783 241.5%20trillion,fishing%20%2839%20million%29%20and%20fish%20farming%20%2820. 785 5%20million%29. Thompson, B. S. (2022). Blue bonds for marine conservation and a sustainable ocean Pr 786 ep 784 rin 780 787 economy: Status, trends, and insights from green bonds. Marine Policy, 144, 105219. This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317 789 UNEP. (2021). State of Finance for Nature. Available online: 790 https://www.unep.org/resources/state-finance-nature 791 we d 788 White, N. (2023). Nuveen Holds 80% of Rare Blue Bond Linked to Debt-Swap Deal. March 793 7, 2023. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-03-07/nuveen-backs-rare-blue- 794 bond-in-debt-swap-deal-for-barbados#xj4y7vzkg 795 ev ie 792 World Resource Institute. (2020). 7 Ways to Bridge the Blue Finance Gap. Available online: 797 https://www.wri.org/insights/7-ways-bridge-blue-finance-gap ee rr 796 798 zu Ermgassen, S. O., Maron, M., Walker, C. M. C., Gordon, A., Simmonds, J. S., Strange, 800 N., ... & Bull, J. W. (2020). The hidden biodiversity risks of increasing flexibility in 801 biodiversity offset trades. Biological Conservation, 252, 108861. ot p 799 802 803 tn 804 805 Pr ep 807 rin 806 808 This preprint research paper has not been peer reviewed. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4509317