Anastasios Tsonis - An Introduction to Atmospheric Thermodynamics (2007, Cambridge University Press) - libgen.li

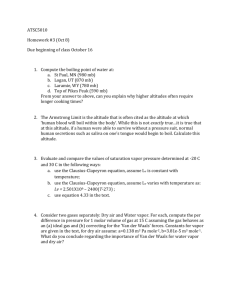

advertisement