Culture and Diversity in Organization Creativity and Performance

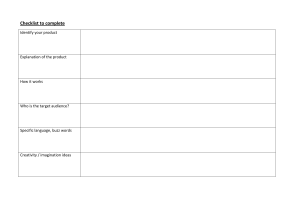

advertisement