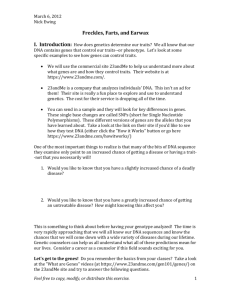

CASE: E-688 DATE: 02/06/20 23ANDME: A VIRTUOUS LOOP Changing health care is hard. If you are looking for an IPO or a short-term exit, you are not the right match for us. I’m looking for people who genuinely buy into the vision and want to be along for the ride, but it’s going to be super bumpy. I can’t promise you timelines. I can’t promise you exactly how things are going to happen. But I promise you the vision is stable. —23andMe CEO and Cofounder Anne Wojcicki1 Sporting a company logo t-shirt and running shorts, 23andMe founder and CEO Anne Wojcicki pushed open the door to her office and sat down at her desk on the fourth floor of the company’s Mountain View headquarters. It was a cool, damp, overcast day in early May 2019, but the low cloud cover and shortage of sunlight made it feel more like mid-winter than early spring. Wojcicki had completed a workout in the downstairs company gym, and she hoped to send a handful of emails before heading home. Wojcicki had eschewed the typical spacious woodpaneled trappings of executive offices, preferring to house herself in a cramped, non-descript fishbowl room in a hallway adjacent to the elevator. With its two transparent glass walls and white circular table, the enclosure resembled a generic conference room, if not for the holiday cards and family photos Wojcicki had taped below the whiteboard. Since founding the company in 2006, Wojcicki had grown 23andMe into the world’s largest source of genetic information. While Wojcicki’s original concept of a direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing kit had scaled to over 10 million customers, with willing research participants contributing their ancestry, health history, genotypic, and phenotypic data to the platform, 23andMe had also built substantial drug development capabilities since 2015. The company was now evaluating 13 pre-clinical therapeutic targets across indications ranging from cancer to asthma—targets that had been identified from a pipeline generated by the company’s vast genetic database. 23andMe’s pharmaceutical efforts possessed near-infinite potential to harness 1 Interview with 23andMe CEO and Cofounder Anne Wojcicki, May 15, 2019. All subsequent quotations are from this interview unless otherwise noted. Jeffrey Conn (MS 2018) and Lecturer Robert Siegel prepared this case as the basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. Copyright © 2020 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. Publicly available cases are distributed through Harvard Business Publishing at hbsp.harvard.edu and The Case Centre at thecasecentre.org; please contact them to order copies and request permission to reproduce materials. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any means –– electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise –– without the permission of the Stanford Graduate School of Business. Every effort has been made to respect copyright and to contact copyright holders as appropriate. If you are a copyright holder and have concerns, please contact the Case Writing Office at businesscases@stanford.edu or write to Case Writing Office, Stanford Graduate School of Business, Knight Management Center, 655 Knight Way, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305-5015. 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 p. 2 the power of genetic information to cure human disease. However, the segment also created new challenges for Wojcicki and her leadership team. How would she balance the competing funding and organizational needs of both sides of the organization and effectively manage her time, while maintaining a single, unified company culture in the process? THE HUMAN GENOME The human genome represents the complete set of genes (estimated at approximately 25,000 in number) found in virtually all of the trillions of cells in the human body, which provide the operating instructions for each individual. Genes are made up of deoxyribonucleic acid, also known as DNA, strung together into 23 “volumes of information” called chromosomes. Human beings possess two sets of each chromosome, with a set inherited from each parent. The wellknown double helix structure of DNA is connected by rungs of approximately 3 billion base pairs, represented by four chemical bases or nucleotides known most commonly by the letters A (adenine), G (guanine), C (cytosine), and T (thymine) (see Exhibit 1). These nucleotides are key structural elements for the genes that individually or in combination determine—sometimes along with the environment—everything from a person’s hair color to their predisposition for Alzheimer’s disease. Approximately 99 percent of DNA sequences are identical across the human population.2 However, Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs, typically pronounced “snips”) represent variations in DNA sequences and occur “every 100 to 300 bases along the 3-billion base human genome.”3 SNPs are alterations in the set of genetic instructions that are thought to provide the genetic markers for human beings’ responses to disease, environmental factors, and drugs.4 For example, an A instead of a G on the AR gene may indicate a higher likelihood for male pattern baldness. Other variations in nucleotide sequences may be associated with celiac disease, cystic fibrosis, or asthma. Since the completion of the U.S. Department of Energy and National Institutes of Health’s Human Genome project in 2003, scientists had published hundreds of studies that described the associations between SNPs and a wide variety of specific diseases, traits, and conditions. These studies opened the door for the personal genomics industry by providing a platform for which DNA—often obtained through a simple saliva sample—could uncover an individual’s genetic map. WOJCICKI’S PATH After receiving her bachelor’s degree in biology from Yale University in 1996, Anne Wojcicki moved to New York City to work as a health care analyst at a Wall Street hedge fund. The deeper she dove into the industry, the more unsettled she became about how its main players— the physicians, insurance companies, and hospitals—were so mired in the structural and financial complexities that they had lost sight of the patients they were supposed to serve. After attending a conference in Washington, D.C., Wojcicki recalled, “I just realized that so many people are 2 Understanding Genetics: A District of Columbia Guide for Patients and Health Professionals, Genetic Alliance; District of Columbia Department of Health, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK132152/ (November 26, 2019). 3 Ibid. 4 Ibid. 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 p. 3 making money on health care’s inefficiencies, it’s not going to change from within.”5 Wojcicki knew that she would not pursue a lengthy career on Wall Street long; she instead felt compelled to be part of a company that worked to improve the health care system for individuals. A few months prior, Wojcicki had met Rockefeller University scientist Markus Stoffel at an investment dinner. Stoffel described a genetic project he was working on to examine the genetic associations of a handful of conditions in a small population in the Micronesian island of Kosrae. Per Wojcicki’s recollection, “He said they had so much data it was overwhelming…but also not enough data to make sense of things. We talked about what would happen if you could get the world’s DNA. And he said it would change the world.”6 Wojcicki then met Linda Avey, an executive at Affymetrix and an early pioneer in the development of genetic research tools. Wojcicki was dating Google co-founder Sergey Brin at the time, and Brin’s mother had Parkinson’s Disease. Affymetrix was working on a Parkinson’s related initiative, and Brin asked Wojcicki to join a meeting with Avey. Wojcicki quickly realized that she and Avey had much more in common than an interest in Parkinson’s Disease – they were both passionate about genetics and consumer empowerment. Together with Avey’s former boss, Paul Cusenza, the trio hatched the idea for 23andMe, named for the 23 pairs of chromosomes present in human DNA. In 2006, the company launched with seed funding provided by Google, a company with which Wojcicki had close ties.7 Describing the early mission of 23andMe, Wojcicki recalled the HIV patient advocacy movement of the late 1980s and early 1990s: “I wanted to harness that kind of anger and agitation and the demand for more transparency…. 23andMe was set out to activate a population that wants to drive change in health care.”8 In November 2007, 23andMe launched its first DTC genetic test for a retail price of $999. A year later, 23andMe launched its research program. Upon purchasing the test from 23andMe’s website, customers were asked to fill out a health history survey, with the option to participate in research that allowed 23andMe to study their de-identified genetic information and survey answers. Consumers could additionally grant permission for 23andMe to re-contact them for future research opportunities. The customer then received a DNA kit in the mail, provided a saliva sample according to the kit directions, and mailed the sample directly to 23andMe’s contracted laboratory. The laboratory used genotyping to capture each person’s unique genetic profile. The SNPs captured in an individual’s profile were then analyzed by a complex algorithm to generate personalized genetic reports. Within four to six weeks of mailing the sample, customers could access their health and ancestry results via a password-protected, encrypted website. 5 Adapted from “The Industrialist’s Dilemma Session 4: Anne Wojcicki, 23andMe,” https://medium.com/theindustrialist-s-dilemma/a-consumer-first-healthcare-vision-6c5fcf4d58c1#.g2p9ax9dm (November 21, 2016). 6 Elizabeth Murphy, “Inside 23andMe founder Anne Wojcicki’s $99 DNA Revolution,” Fast Company, October 14, 2013, https://www.fastcompany.com/3018598/for-99-this-ceo-can-tell-you-what-might-kill-you-inside-23andMefounder-anne-wojcickis-dna-r (November 29, 2016). 7 In its earliest days, Google operated out of Wojcicki’s sister’s garage and soon after, Wojcicki began dating, and later married, Google cofounder Sergey Brin. 8 “The Industrialist’s Dilemma Session 4: Anne Wojcicki, 23andMe,” loc. cit. 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 p. 4 Within six years, 23andMe outpaced competitors deCODE Genetics, Navigenics, Pathway Genomics, and Counsyl Genetics to become the leading global genetics testing platform. By the fall of 2013, the company’s database included testing results from more than 400,000 people, making it the world’s largest repository of individual genetic information. Of those 400,000 people, approximately 80 percent had agreed to contribute their health and genetic information to 23andMe’s research. 23andMe’s testing provided consumers information on more than 263 factors, from the individual’s status as carrier of genetic diseases, to likely responses to drugs, as well as ancestral information. The research team at 23andMe also published impactful peerreviewed academic papers, including the discovery of three genetic variations associated with Parkinson’s, and a study that linked genes related to breast size to increased breast cancer risk.9,10 The company additionally published evidence that 23andMe was able to replicate over 180 genetic associations using self-reported medical data, as opposed to medical records, which had long been the “preferred source of retrospective information on medical conditions.”11 Wojcicki and her team raised nearly $90 million of capital in this timeframe, to fuel the company’s growth and research activities. Despite the increasing consumer and research momentum, regulatory issues soon jolted the company. In November 2013, 23andMe received a warning letter from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to cease selling its health reports (see Exhibit 2). The FDA believed that 23andMe had failed to provide complete and timely information to meet the government’s requirements for regulatory approval of its products. Cited among the FDA’s concerns was “the public health consequences of inaccurate results from the [Personal Genome Service] PGS device.”12 Due to the efforts of newly hired Chief Legal and Regulatory Officer Kathy Hibbs and her team, the company was able to re-launch a curtailed set of its health reports with the FDA’s blessing in October 2015, at a price point of $199. The test allowed healthy individuals to be notified if they carried a genetic variant related to 36 hereditary conditions, including cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anemia, Tay-Sachs disease, and beta thalassemia. However, the transition to selling a regulated product was costly; Wojcicki was forced to overhaul 23andMe’s entire organization, including its corporate reporting structure, compliance, and quality control policies. In April 2017, the FDA granted 23andMe authorization to restore additional health reports, including testing for Parkinson’s risk and Alzheimer’s disease.13 In September 2017, the company announced that Sequoia Capital had led a $250 million investment round in the company (see Exhibit 3), and that partner Roelof Botha would be taking a board seat. The growth phase was well underway. 9 “23andMe Discovers Genetic Variant That May Protect Those at High Risk for Parkinson’s Disease,” 23andMe website, October 25, 2011, https://mediacenter.23andme.com/blog/23andme-discovers-genetic-variant-that-mayprotect-those-at-high-risk-for-parkinsons-disease/ (November 29, 2016). 10 “23andMe Contributes to Genetic Discoveries Related to Breast Size and Breast Cancer,” 23andMe website, July 23, 2012, https://mediacenter.23andMe.com/blog/23andMe-contributes-to-genetic-discoveries-related-tobreast-size-and-breast-cancer/ (November 28, 2016). 11 Joyce Y. Tung, et al., “Efficient Replication of over 180 Genetic Associations with Self-Reported Medical Data,” PLoS ONE, August 17, 2011, http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0023473 (January 14, 2017). 12 “Inspections, Compliance, Enforcement, and Criminal Investigations,” U.S. Food and Drug Administration, November 22, 2013, http://www.fda.gov/ICECI/EnforcementActions/WarningLetters/2013/ucm376296.htm (November 29, 2016). 13 Adam Bluestein, “After A Comeback, 23andMe Faces Its Next Test,” Fast Company, August 7, 2016, https://www.fastcompany.com/40438376/after-a-comeback-23andme-faces-its-next-test (August 1, 2019). 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 p. 5 In 2018 the company received two further FDA authorizations, one for Genetic Health Risks for BRCA1/BRCA2 Selected Variants associated with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, and a second for Pharmacogenetic Reports providing information about how an individual’s genetic variants may affect how they process certain medications. In early 2019, 23andMe received additional regulatory clearance from the FDA to provide customers with the Genetic Health Risks for MUTYH-Associated Polyposis, a hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome. While still working through various FDA authorizations to offer more health information, in April 2015 Wojcicki brought in Dr. Richard Scheller, formerly executive vice president of research and early development for biotechnology pioneer Genentech, to explore the concept of leveraging the company’s genetic data for use in drug discovery. Scheller assembled a team of experienced pharmaceutical professionals, building a state-of-the-art research facility in South San Francisco. In addition, the company signed research collaborations with Genentech and Pfizer. Following those and other collaborations, 23andMe announced a $300 million investment round and accompanying 50-50 drug development joint venture with GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) in July 2018. By the spring of 2019, less than five years after the FDA warning letter, Wojcicki viewed the first crucial phase of the company’s development as complete. She had achieved her goals of bringing back consumer access to 23andMe’s valuable health reports, and her company had compiled an unprecedented database of 8.5 million genotyped individuals. TIME TO EXECUTE Wojcicki finally felt that she had the large dataset, consumer momentum, and talented executive team in place to be able to execute on her vision of using genetic data to revolutionize the health care industry. She had deftly handled significant leadership turnover as the company matured, including the exit of 23andMe President Andy Page, who had been hired to allow Wojcicki to shed some of her day-to-day management responsibilities. Upon Page’s exit in 2016, Wojcicki re-assumed most of Page’s responsibilities and regained full daily control. She stated: Andy Page stepped in at a crucial time when I was getting divorced and distracted from day to day responsibilities at the company. By 2016, I realized it was essential I take over day to day responsibilities of the company. I had the vision for the company, and I couldn’t effectively implement that vision without having direct reports again. I had a wonderful coach who encouraged me to step up and gave me the confidence to know that I can, in fact, lead the company effectively. I am absolutely comfortable now with my weaknesses, and I know how to hire to support them. I recognize that everyone at the company has talents, but no one is good at everything. I have learned how to hire well and fire fast - the wrong senior leadership is detrimental for the company and that individual. The main thing I learned after 12+ years is confidence in my leadership and acceptance of my strengths and weaknesses. Wojcicki’s passion translated in her ability to raise capital, and her transparent and straightforward style ensured that her investors had appropriate expectations. When Wojcicki launched her company’s Series F investment round in mid-2017, her investment bank lined up an 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 p. 6 initial meeting with Sequoia Capital. Wojcicki was hesitant to take the meeting, as Sequoia had declined to participate in 23andMe’s prior Series A funding round and instead backed a competitor, Navigenics. Wojcicki agreed to meet with the Sequoia team but told the bankers she would be nothing short of direct and honest about Sequoia’s prior behavior and her plans for the company. Wojcicki recalled kicking off the meeting:14 I am here presenting but not because I am trying to win you over. You guys made the last ten years of my life difficult. Navigenics guys single-handedly coined the term ‘recreational genomics’ and created a bad reputation for consumer genomics. You’ve hurt this industry. I am here because I have seen how powerful it can be to have a firm like Sequoia on your side and I wish we had that kind of support for the last decade. But I have also come to realize we don’t need it. So I am here to tell you about what we are doing but I am not here to try and win you over. We are going to win. We have been through a lot and everyone dismissed us. I need people behind us that support me and the company for the long term. I can tell you where we are going but I can’t tell you exactly when we are going to get there. Changing health care is hard. If you are looking for an IPO or a short term exit, you are not the right match for us. I’m looking for people who genuinely buy into the vision and want to be along for the ride, but it’s going to be super bumpy. I can’t promise you timelines. I can’t promise you exactly how things are going to happen. But I promise you the vision is stable. To Botha, the company’s exponential user growth metrics were clear evidence of 23andMe’s ability to build a successful, scalable product; but he came away most impressed by Wojcicki’s honesty and clarity of thought. Botha commented, “For me, the founder being there and following their moral authority, their vision and their passion, that’s what you want to back.”15 CONSUMER GROWTH 23andMe’s consumer base had grown from 2 million customers to over 10 million in the span of two years, and the company’s consumer unit was in the midst of a massive growth phase. 23andMe sold two separate kits—a $99 Ancestry report and a $199 Health and Ancestry report, and Wojcicki and VP of Business Development Dr. Emily Drabant Conley saw strong reasons to continue to accelerate the size of the company’s consumer data platform. For 23andMe, a genome-wide association study (GWAS) “hit” was a successful determination across a population of individuals that shared genetic variations were associated with a particular trait or disease condition. As 23andMe’s participant population scaled over the past five years, the research team reported no plateau in GWAS hits (see Exhibit 4). Put simply, there were no diminishing returns in scientific research value to continuing to scale the consumer platform. 23andMe’s user engagement metrics were nearly as impressive as its user growth. In the previous 90 days, 60 percent of the company’s aggregate 10 million customer base had logged into their 23andMe profile, and 48 percent of the oldest annual cohort of customers (acquired in the 2007 to 2008 timeframe) had done so as well, pointing to extremely high user retention rates. 14 Navigenix failed to develop a significant customer base and was acquired by Life Technologies in 2012. Interview with Sequoia Capital partner Roelof Botha, June 28, 2019. All subsequent quotations are from this interview unless otherwise noted. 15 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 p. 7 This devoted and active customer base led Conley and her team to devote resources to building a new business line in clinical trial recruitment. However, Wojcicki and the management wrestled with numerous fundamental business issues for the consumer segment, hoping to make it more profitable and sustainable while maintaining its growth trajectory. The consumer unit was on the path to near-term profitability, as contribution margins continued to improve with increased sales; however, it was still operating at a loss and sustained negative cash flow. Recalling a prior conversation with board member Richard Scheller, the company’s former chief scientific officer, Botha pondered at what point in the company’s life cycle it made financial sense to increase pricing on the consumer products to generate positive cash flow, trading off profitability for reduced growth. He remarked: Richard [Scheller] sometimes would appropriately say, are we spending too much on marketing, do we have the right margin targets for the kit business? Because you can sell them to a lot more customers if you give them away for free, but that’s not a recipe for success. DATA CONCERNS While Wojcicki and the management team worked through key business issues, Vice President of Research Dr. Joyce Tung was tasked with enabling the numerous primary applications of 23andMe’s customer data. Tung and her 80-person team developed the core data infrastructure to ingest and analyze the massive troves of data 23andMe acquired each day. While the scale and complexity of the data problems had grown dramatically since Tung had joined the company in 2007, privacy and information security had emerged as a significant public issue as well. In contrast to other organizations, especially consumer technology companies, in which employees do not directly interface with external oversight bodies, her team dealt directly with an external institutional review board (IRB) to monitor the ethics, policies, and data sharing involved in 23andMe’s research activities. The structure was similar to academic settings, in which principal investigators routinely interacted with IRBs. Tung believed that the structure made researchers feel a greater responsibility to 23andMe’s consumers, who were the participants in the company’s research projects. Tung continued: One of the core values is that behind every data point is a human being. One of the things that you have to remind people is your friends are in here, your mother is in here, even your children might be in here. You have to take that responsibility very seriously. If you lose the trust of the public, the scientific community, the medical community, you do not have a business.16 Like many other technical groups across Silicon Valley, Tung’s group suffered from a shortage of available talent to scale her team. She sought out individuals with a unique combination of programming, statistics, and biology experience. While there was a larger pool of individuals with pure data science training, Tung found that employees with experience working on biological systems had already developed keen intuition as to whether their analysis would be meaningful and scientifically relevant. Candidates without that experience took significant time 16 Interview with 23andMe Vice President of Research Dr. Joyce Tung, May 15, 2019. All subsequent quotations are from this interview unless otherwise noted. 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 p. 8 to develop that intuition, if ever. Last, Tung worried about the ability to maintain strategic alignment and transparent communications between the diverse groups, roles, and systems with which she and her team interacted. In many ways, this was the hardest part of her role. She remarked: People will look at research and therapeutics and say, “Oh, they’re all scientists, it must be easy,” but the difference between a computational biologist and a wet lab biologist is pretty wide. On top of that, you have a scientist versus an engineer versus a marketing person. Everybody needs to hold hands and hug. THERAPEUTICS 23andMe’s therapeutics group was running at full steam as well. The company’s July 2018 agreement with GSK provided the company with $300 million in funding and established a fouryear joint venture agreement in which GSK and 23andMe would each bear 50 percent of the drug development costs and own 50 percent of the (hopefully) successful commercialized therapies. The joint venture had three stated purposes: to improve target selection to allow safer, more effective “precision” medicines to be discovered; to support identification of patient subgroups more likely to respond to targeted treatments; and to allow for more effective identification and recruitment of patients for clinical studies.17 GSK also became 23andMe’s exclusive collaborator for drug discovery during the life of the agreement, and the companies established a Joint Steering Committee to ensure each side operated in good faith and contributed equal resources to the programs. Both teams believed that 23andMe’s massive genetic dataset could reduce the cost and timeline to find viable targets and bring drugs to market, disrupting the pharmaceutical industry in the process. With the assistance of GSK, 23andMe’s 90-person therapeutics team along with members of Tung’s research team were simultaneously developing different programs across multiple disease areas, including oncology, respiratory, and cardiovascular diseases. Scheller, whom Wojcicki originally recruited to commence 23andMe’s therapeutics effort in 2015, left the company via planned retirement in 2019; he now sat on the company’s board of directors, and Dr. Kenneth Hillan replaced him as head of therapeutics. Wojcicki and the management team all saw the tremendous potential for the therapeutics group to cure numerous diseases and create value for the company, but they also understood the large quantum of capital and resources required to advance so many programs, especially if they advanced to clinical stages. Drug development was a high-risk undertaking, with historical approval rates measured between 9 and 14 percent for programs that reached Phase I clinical trials, and clinical trial costs ranging from $10 million to $350 million.18,19 Conley remarked: 17 “GSK and 23andMe sign agreement to leverage genetic insights for the development of novel medicines,” GSK website, July 25, 2018, https://www.gsk.com/en-gb/media/press-releases/gsk-and-23andme-sign-agreement-toleverage-genetic-insights-for-the-development-of-novel-medicines/ (August 4, 2019). 18 Chi Heem Wong, “Estimation of clinical trial success rates and related parameters,” Biostatistics, Vol. 20, Issue 2, pp. 273-286, January 31, 2018, https://academic.oup.com/biostatistics/article/20/2/273/4817524 (August 4, 2019). 19 Thomas J. Moore, “Estimated Costs of Pivotal Trials for Novel Therapeutic Agents Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, 2015-2016,” JAMA Internal Medicine, November 2018, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2702287 (August 4, 2019). 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 p. 9 When you’re a small biotech, you pick one narrow area, so that you can go deep. Now, all of a sudden, we have targets in all of these different disparate areas, and there was an appreciation that, to move fast, it would be wise to work with someone that could help us with scale and speed. Because we were doing this hypothesis-agnostic approach, we were just letting the data drive us and help us find targets. From a strategic standpoint, that was why partnering with a group like GSK was intriguing. There was real complementarity; we brought this incredible database and some really great genomics science, the ability to find these novel targets that we believe are more likely to be effective as therapies. And they brought a 100,000-person organization, with a proven track record of actually going from a target to a therapy.20 REGULATORY LANDSCAPE On the compliance front, Chief Legal and Regulatory Officer Kathy Hibbs remained committed to strengthening 23andMe’s relationships with the FDA and other government organizations. After 23andMe re-launched a shortened set of health reports in 2015, the company received the FDA’s first-ever authorization to market direct-to-consumer “Genetic Health Risk” reports in April 2017, including tests for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, which were followed by authorizations and a clearance for a Genetic Health Risk report for selected variants of the cancer-linked BRCA1/BRCA2 genes, and Pharmacogenetic information and clearance for additional cancer health risk information related to MUTYH-Associated Polyposis. The FDA evaluated 23andMe’s submissions for genetic health risk reports through its de novo classification pathway, a regulatory process for low- to moderate-risk medical devices that were deemed first-of-a-kind. For some carrier and genetic health risk reports, FDA also indicated that it would create an exemption for subsequent reports, opening a clear regulatory pathway for future health tests. Despite the regulatory clarity, the company’s health products were not exempt from public scrutiny. In April 2019, a study by diagnostics competitor Invitae claimed that nearly 90 percent of participants who carried BRCA gene mutations would have been missed by 23andMe’s BRCA genetic testing.21 Some members of the breast cancer research community were concerned that this study could indicate that customers were unable to grasp the limitations of 23andMe’s direct-to-consumer genetic tests. Dr. Mary Claire King, who discovered the BRCA1 region of the genome, stated in the New York Times, “The FDA should not have permitted this out-of-date approach to be used for medical purposes…. Misleading, falsely reassuring results from their incomplete testing can cost women’s lives.”22 However, 23andMe specifically and repeatedly warned consumers that it tested for only three specific variants that were prevalent among Ashkenazi Jews and not all known variants, so the company was in no way deceptive. As part of the FDA premarket review process, the company additionally had been required to submit several user comprehension studies, which showed that 20 Interview with 23andMe Vice President of Business Development Dr. Emily Drabant Conley, May 15, 2019. Numerous BRCA genetic mutations are widely accepted to put women at an elevated risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer. 22 Heather Murphy, “Don’t Count on 23andMe to Detect Most Breast Cancer Risks, Study Warns,” The New York Times, April 16, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/16/health/23andme-brca-gene-testing.html (August 4, 2019). 21 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 p. 10 U.S. consumers—regardless of ethnicity, age, gender, or educational level—understood the product and its limitations and warnings. Further, 23andMe conducted its own study and found that 44 percent of people carrying one of the three variants the company tested for had no family history of BRCA-related cancer, and 21 percent did not self-report any Jewish ancestry, meaning that these customers would not have been caught by traditional guidelines for BRCA screening.23 The company also emphasized that 23andMe was not a clinical test and required follow-up testing in a health care setting. Hibbs viewed the role of government in the genetic testing market to be extremely important for the company’s forward consumer product strategy, and for the competitive landscape as well. She believed the 2013 FDA warning letter was partially the result of the company’s general lack of understanding of its incumbent genetics testing competitors, and the regulations that governed their behavior in the market. Hibbs also noticed that different presidential administrations had varying views on the appropriate levels of regulation. As a result, market enforcement levels could swing wildly depending on the political group in power. She stated: Look, if the people you are displacing are highly regulated, you’re probably going to be regulated, because there is a system that’s set up to do that, even if you have a different modality…. Now, you have all of these largely prescription products that are being sold to consumers, and they’re not even adhering to standard fair advertising where they’ll make a comparison claim…. So that is something that’s obviously frustrating for us because we’re dealing with a totally un-level playing field.24 Hibbs felt that 23andMe was not only disrupting the business of traditional genetics labs, but also displacing genetic counselors by directly arming consumers with their own health information. The company’s product violated the historical paternalistic norms of health care in Western societies, and the prevailing opinion that patients couldn’t deal with the potential stress of receiving their own results—thus the need for skilled intermediaries to relay and make sense of the data on the patient’s behalf. Hibbs was also personally intrigued that the perceived knowledge of families and individual identity was shaped by sociological issues that sometimes were in conflict with genetics. She remarked: Physicians make assumptions, on the basis of what we look like, on the basis of last names, many of which have been anglicized over time or you have a married last name, and they make assumptions that you know what your family history is, and most people don’t. People think, “Well, my grandmother was Jewish but I don’t practice” and the same thing is true for other ethnicities where there’s been prejudice and disadvantage. In order to save money, we do screening on the basis of your family health history. Did somebody else in your family have a BRCAdriven cancer? Are you yourself Jewish? And because we do that, you may 23 Ruth Tennen, Sarah Laskey et al., “Identifying Ashkenazi Jewish BRCA1/2 founder variants in individuals who do not self-report Jewish ancestry,” medRxiv, August 9, 2019, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/19001032v1 (October 23, 2019). 24 Interview with 23andMe Chief Legal and Regulatory Officer Kathy Hibbs, May 15, 2019. Subsequent quotations are from this interview unless otherwise noted. 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 p. 11 never know, because if we just go back 25 years we didn’t even tell people they had cancer. GROWTH PATH AND STRUCTURE CONCERNS Wojcicki thought through the complex, multivariate equation of how to optimally grow her business. For the consumer arm, numerous options were on the table. Given the platform’s strong user engagement metrics, Wojcicki was convinced that consumers would be willing to pay for incremental services beyond the initial health and ancestry reports they received, but could her team implement a subscription service without alienating the portion of their user base that might not subscribe? Were there other services the company could offer that would not only generate revenue but also align with the company’s mission of empowering customers? Conley and her team were exploring additional external licensing and partnership strategies as well. In January 2019, 23andMe announced a partnership with AI-enabled disease management platform Lark to integrate genetic information into two of Lark’s health programs. Researchers from 23andMe found several lifestyle choices associated with body weight differences in individuals with similar genetic information, potentially providing insight into how lifestyle impacts weight and general wellness. Wojcicki and Conley saw the potential to launch similar product integrations as not only a key source of growth, but a way to create near-term meaningful impact for the health of its customers. Wojcicki stated in the joint Lark/23andMe partnership press release: Access to your genetic information is really just the beginning—using that information to prevent serious health consequences is the next critical step. Our collaboration with Lark enables 23andMe customers to use their genetic information in a clinically validated program to help them make lifestyle changes to improve their health.25 The clinical trial recruitment business effort was another obvious path. Patient recruitment for high-value clinical trials often cost thousands of dollars per eligible patient, lengthening clinical trial timelines and increasing trial costs.26 Millions of people in 23andMe’s database had consented for e-mail contact and provided the company with their disease information and address, so 23andMe was incredibly well-positioned to match willing customers with clinical trial patient demand. On the therapeutics side, Wojcicki and Conley evaluated how to maximize the value of 23andMe’s partnership with GSK, to increase the likelihood of success of their therapeutic targets. The length of the partnership agreement was fixed, giving both 23andMe and GSK the potential to opt out or renegotiate in 2022. Conley felt confident that the company should eventually have some sort of commercialization partner—it made no sense for 23andMe to prematurely build up its own salesforce to market as of yet unapproved products across 25 “Lark Health and 23andMe Collaborate to Integrate Genetic Information in Two New Health Programs,” 23andMe website, January 8, 2019, https://mediacenter.23andme.com/press-releases/lark-health-and-23andmecollaborate-to-integrate-genetic-information-in-two-new-health-programs/ (August 5, 2019). 26 Mary Jo Lamberti, PhD and Adam Mathias, MPH, “Evaluating the Impact of Patient Recruitment and Retention Practices,” Drug Information Journal, July 13, 2012, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0092861512453040 (August 5, 2019). 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 p. 12 numerous varied indications. But did it make sense to exclusively partner with a single firm? Could 23andMe be better off cutting multiple development agreements across numerous pharmaceutical companies to have as many “shots on goal” as possible? On the downside, each development program would demand additional capital and further dilute the equity stakes of the existing investors and leadership team. Organizational concerns loomed on the horizon for Wojcicki as well. The risk profiles of the consumer and therapeutics arms were vastly different. The consumer business was evolving to become a sustainable platform with recurring revenue, while the therapeutics group would always be a high-risk, capitally intensive, and “hit-driven” business. However, the two sides were strategically intertwined—the therapeutics arm relied on the consumer dataset’s GWAS hits (genetic commonalities associated with specific traits or disease conditions) to populate its initial target funnel. Conley described the company’s current operating philosophy: We think about it as a big virtuous loop. You have this great consumer product where consumers are learning about themselves, and they’re in the driver’s seat. If they want to opt-in and participate in research, they can, and there’s the potential to create a benefit. Sometimes in the near term just through the product, but then there’s the potential for a longer-term benefit, if we discover new genetics, we can develop that into a therapy that could then be available for consumers. How quickly could Wojcicki push for the consumer side to be self-sustaining while funding the development of the therapeutics group? The competition for resources could make capital allocation difficult and eventually lead to tension between the groups. Wojcicki would need to be incredibly intentional about maintaining a unified culture and mission for her firm and aligning the interests of both sides of the business. THE BIG DREAM Setting aside internal considerations, Wojcicki was excited about the market opportunity that lay ahead for 23andMe. Chronic diseases comprised a large portion of health care spending in the developed world, and many of these diseases, such as diabetes, were highly preventable with exercise and weight loss. Wojcicki believed that 23andMe’s health information could help consumers change their behavior and ultimately reduce the prevalence and severity of those ailments. Wojcicki aimed to create a world of health care delivery outside of the existing system based on a mobile interface; Apple, Google, Amazon, and the largest public technology companies had already entered the space, with varying levels of adoption and minimal systemwide impact. Many individuals in the United States and beyond had negative experiences with health care, and Wojcicki wanted to use the power of technology to improve the quality of that experience. Her belief that consumers would in fact change their behavior conflicted with the broader medical community’s prevailing view that promoting self-directed health and lifestyle changes was largely ineffective. Wojcicki ran her company in alignment with those preventive goals; she had installed signs around 23andMe’s headquarters that urged employees to lead active lives. As an example, there were signs posted in the elevator and stairwells featuring photos of 1980s aerobics guru Richard Simmons, which provided employees with the aggregate number of steps achieved from the 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 p. 13 ground floor and touted the benefits of high-intensity incidental physical activity (see Exhibit 5). She also believed that the company’s starting point from outside of the system was a huge advantage—23andMe’s lack of history and evolutionary lock-in provided it with greater flexibility to partner and innovate. But in order to scale quickly, her company might have to form meaningful partnerships with large players who operated within that existing flawed system. With the largest database of both genetic and phenotypic (non-genetic) information, and the ability to re-contact research participants for ongoing studies, Wojcicki was confident that the company possessed the internal capabilities to achieve her vision. The distinctive competence of her firm had been established—it was now up to her to set 23andMe’s strategic direction. Wojcicki got up from her desk, locked her computer, and took the stairs down to the garage. She concluded: I have the ability to execute. It’s about making the right decisions. Part of the philosophy here is we’ll make lots of wrong decisions. A lot of decisions could be the wrong timing, or it doesn’t work for one reason or another, but you only figure that out by trial and error. We’re going to make a ton of mistakes and a ton of things will not happen. I believe in the long run that the right thing to do will pay off. There are opportunities. Part of the challenge that we have in health care is so many of the incentives fundamentally are wrong. So, I have to swim against the current for a period of time. Ultimately, in time, things will change. 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 p. 14 Exhibit 1 DNA Double Helix Source: Photo courtesy of DOE Joint Genome Institute, via How Stuff Works, https://science.howstuffworks.com/life/genetic/designer-children1.htm (November 26, 2019). 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 p. 15 Exhibit 2 2013 FDA Warning Letter to 23andMe Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Food and Drug Administration 10903 New Hampshire Avenue Silver Spring, MD 20993 Nov 22, 2013 Anne Wojcicki CEO 23andMe, Inc. 1390 Shoreline Way Mountain View, CA 94043 Document Number: GEN1300666 Re: Personal Genome Service (PGS) WARNING LETTER Dear Ms. Wojcicki, The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is sending you this letter because you are marketing the 23andMe Saliva Collection Kit and Personal Genome Service (PGS) without marketing clearance or approval in violation of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (the FD&C Act). This product is a device within the meaning of section 201(h) of the FD&C Act, 21 U.S.C. 321(h), because it is intended for use in the diagnosis of disease or other conditions or in the cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease, or is intended to affect the structure or function of the body. For example, your company’s website at www.23andMe.com/health (most recently viewed on November 6, 2013) markets the PGS for providing “health reports on 254 diseases and conditions,” including categories such as “carrier status,” “health risks,” and “drug response,” and specifically as a “first step in prevention” that enables users to “take steps toward mitigating serious diseases” such as diabetes, coronary heart disease, and breast cancer. Most of the intended uses for PGS listed on your website, a list that has grown over time, are medical device uses under section 201(h) of the FD&C Act. Most of these uses have not been classified and thus require premarket approval or de novo classification, as FDA has explained to you on numerous occasions. Some of the uses for which PGS is intended are particularly concerning, such as assessments for BRCArelated genetic risk and drug responses (e.g., warfarin sensitivity, clopidogrel response, and 5-fluorouracil toxicity) because of the potential health consequences that could result from false positive or false negative assessments for high-risk indications such as these. For instance, if the BRCA-related risk assessment for breast or ovarian cancer reports a false positive, it could lead a patient to undergo prophylactic surgery, chemoprevention, intensive screening, or other morbidity-inducing actions, while a false negative could result in a failure to recognize an actual risk that may exist. Assessments for drug responses carry the risks that patients relying on such tests may begin to self-manage their treatments through dose changes or even abandon certain therapies depending on the outcome of the assessment. For example, false genotype results for your warfarin drug response test could have significant unreasonable 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 p. 16 risk of illness, injury, or death to the patient due to thrombosis or bleeding events that occur from treatment with a drug at a dose that does not provide the appropriately calibrated anticoagulant effect. These risks are typically mitigated by International Normalized Ratio (INR) management under a physician’s care. The risk of serious injury or death is known to be high when patients are either noncompliant or not properly dosed; combined with the risk that a direct-to-consumer test result may be used by a patient to self-manage, serious concerns are raised if test results are not adequately understood by patients or if incorrect test results are reported. Your company submitted 510(k)s for PGS on July 2, 2012 and September 4, 2012, for several of these indications for use. However, to date, your company has failed to address the issues described during previous interactions with the Agency or provide the additional information identified in our September 13, 2012 letter for (b)(4) and in our November 20, 2012 letter for (b)(4), as required under 21 CFR 807.87(1). Consequently, the 510(k)s are considered withdrawn, see 21 C.F.R. 807.87(1), as we explained in our letters to you on March 12, 2013 and May 21, 2013. To date, 23andMe has failed to provide adequate information to support a determination that the PGS is substantially equivalent to a legally marketed predicate for any of the uses for which you are marketing it; no other submission for the PGS device that you are marketing has been provided under section 510(k) of the Act, 21 U.S.C. § 360(k). The Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health (OIR) has a long history of working with companies to help them come into compliance with the FD&C Act. Since July of 2009, we have been diligently working to help you comply with regulatory requirements regarding safety and effectiveness and obtain marketing authorization for your PGS device. FDA has spent significant time evaluating the intended uses of the PGS to determine whether certain uses might be appropriately classified into class II, thus requiring only 510(k) clearance or de novo classification and not PMA approval, and we have proposed modifications to the device’s labeling that could mitigate risks and render certain intended uses appropriate for de novo classification. Further, we provided ample detailed feedback to 23andMe regarding the types of data it needs to submit for the intended uses of the PGS. As part of our interactions with you, including more than 14 face-to-face and teleconference meetings, hundreds of email exchanges, and dozens of written communications, we provided you with specific feedback on study protocols and clinical and analytical validation requirements, discussed potential classifications and regulatory pathways (including reasonable submission timelines), provided statistical advice, and discussed potential risk mitigation strategies. As discussed above, FDA is concerned about the public health consequences of inaccurate results from the PGS device; the main purpose of compliance with FDA’s regulatory requirements is to ensure that the tests work. However, even after these many interactions with 23andMe, we still do not have any assurance that the firm has analytically or clinically validated the PGS for its intended uses, which have expanded from the uses that the firm identified in its submissions. In your letter dated January 9, 2013, you stated that the firm is “completing the additional analytical and clinical validations for the tests that have been submitted” and is “planning extensive labeling studies that will take several months to complete.” Thus, months after you submitted your 510(k)s and more than 5 years after you began marketing, you still had not completed some of the studies and had not even started other studies necessary to support a marketing submission for the PGS. It is now eleven months later, and you have yet to provide FDA with any new information about these tests. You have not worked with us toward de novo classification, did not provide the additional information we requested necessary to complete review of your 510(k)s, and FDA has not received any communication from 23andMe since May. Instead, we have become aware that you have initiated new marketing campaigns, including television commercials that, together with an increasing list of indications, show that you plan to expand the PGS’s uses and consumer base without obtaining marketing authorization from FDA. Therefore, 23andMe must immediately discontinue marketing the PGS until such time as it receives FDA marketing authorization for the device. The PGS is in class III under section 513(f) of the FD&C Act, 21 U.S.C. 360c(f). Because there is no approved application for premarket approval in effect pursuant to 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 p. 17 section 515(a) of the FD&C Act, 21 U.S.C. 360e(a), or an approved application for an investigational device exemption (IDE) under section 520(g) of the FD&C Act, 21 U.S.C. 360j(g), the PGS is adulterated under section 501(f)(1)(B) of the FD&C Act, 21 U.S.C. 351(f)(1)(B). Additionally, the PGS is misbranded under section 502(o) of the Act, 21 U.S.C. § 352(o), because notice or other information respecting the device was not provided to FDA as required by section 510(k) of the Act, 21 U.S.C. § 360(k). Please notify this office in writing within fifteen (15) working days from the date you receive this letter of the specific actions you have taken to address all issues noted above. Include documentation of the corrective actions you have taken. If your actions will occur over time, please include a timetable for implementation of those actions. If corrective actions cannot be completed within 15 working days, state the reason for the delay and the time within which the actions will be completed. Failure to take adequate corrective action may result in regulatory action being initiated by the Food and Drug Administration without further notice. These actions include, but are not limited to, seizure, injunction, and civil money penalties. We have assigned a unique document number that is cited above. The requested information should reference this document number and should be submitted to: James L. Woods, WO66-5688 Deputy Director Patient Safety and Product Quality Office of In vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health 10903 New Hampshire Avenue Silver Spring, MD 20993 If you have questions relating to this matter, please feel free to call Courtney Lias, Ph.D. at 301-796-5458, or log onto our web site at www.fda.gov for general information relating to FDA device requirements. Sincerely yours, /S/ Alberto Gutierrez Director Office of In vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health Center for Devices and Radiological Health Source: “Inspections, Compliance, Enforcement, and Criminal Investigations,” U.S. Food and Drug Administration, November 22, 2013, http://www.fda.gov/ICECI/EnforcementActions/WarningLetters/2013/ucm376296.htm (November 29, 2016). 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 p. 18 Exhibit 3 23andMe: Major Financing Milestones Date Amount/Round October 2007 $8.95 M/Series A June 2009/ December 2009 Undisclosed amount/ Series B November 2010/ January 2011 $31.22 M/Series C December 2012 $57.95 M/Series D July 2015 $115 M/Series E September 2017 $250 M/Series F December 2018 $300 F-1 (Strategic) Investors Genentech, Inc., Google Inc., MDV-Mohr Davidow Ventures, and New Enterprise Associates (NEA) Undisclosed Johnson & Johnson Development Corporation, NEA, Google Ventures, MPM Capital Sergey Brin, Yuri Milner, Anne Wojcicki, Google Ventures, MPM Capital, NEA Fidelity Management and Research Company, Casdin Capital, WuXi Healthcare Ventures, Xfund, Google Ventures, Illumina, MPM Capital, NEA Sequoia Capital, Casdin Capital, Decacorn Capital, Euclidean Capital, Fidelity Management & Research, Growth Technology Partners, Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, Marc Bell Capital Partners, Sapphire Ventures, SharesPost, StraightPath Venture Partners GlaxoSmithKline Sources: Compiled by case authors, using data from 23andMe and PitchBook. 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 Exhibit 4 Proof of Continued GWAS Scaling and Drug Discovery Funnel Source: 23andMe. Source: 23andMe. p. 19 23andMe: A Virtuous Loop E-688 p. 20 Exhibit 5 23andMe Elevator and Stairwell Signage Source: 23andMe.