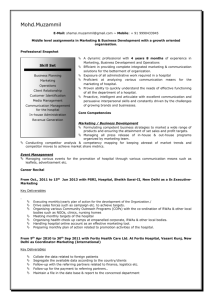

UNIT 10 PARTNERSHIP BETWEEN LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND NON-STATE AGENCIES/ACTORS Structure 10.0 Learning Outcomes 10.1 Introduction 10.2 Need for Partnership 10.3 Bhagidari: A Programme of Government-Citizen Partnership 10.3.1 Working Process 10.3.2 Implementation, Monitoring and Review 10.4 Realising Bhagidari 10.4.1 Bhagidari between RWAs and PUDs/CSAs 10.4.2 Bhagidari on Complex Policy Issues 10.4.3 Internal Bhagidari for Change Management 10.5 Critical Success Gaps 10.6 Bhagidari: A Model of Good Governance 10.7 Conclusion 10.8 Key Concept 10.9 References and Further Readings 10.10 Activities 10.0 LEARNING OUTCOMES After studying this Unit, you should be able to: • discuss the need of partnership between government and citizens at the local level; • explain the features of the partnership initiative, namely, the ‘Bhagidari Programme’ of the Government of Delhi; • highlight the working process and implementation of the Bhagidari Programme; • analyse the critical success gaps in the Programme; and • suggest measures to realise the Programme effectively. 10.1 INTRODUCTION With globalisation, privatisation, and liberalisation making stride in the global scenario since 1980’s, the centralist, hierarchical, secretive and authoritarian traditional bureaucracy found itself with new tasks and challenges. The new wave of reforms called for decentralisation, role for civil society, people’s participation in administration, administrative responsiveness, public-private partnerships, FDIs, downsizing, cost cutting, etc. To keep pace with these reforms bureaucracy, especially at the cutting edge had to change, as it is the point where government and citizen interface takes place. Administration had to undergo reforms and pay more attention to the people and the community. They have now to be inclining towards public interest, public service, democratic citizenship and democratic values. They have now to facilitate and engage in dialogue and discourse with the people and involve them as partners in governance and owners in development. This Unit undergrids this concept of partnership between the government and the people at the local level. In this Unit we will discuss a partnership initiative namely the ‘Bhagidari Programme’ undertaken by the State Government with the people in the National Capital Territory of Delhi. Whereas the Bhagidari Programme encompasses various aspects concerning the citizens of Delhi, such as provision of civic services, school development, women empowerment and social welfare, rural bhagidari etc; in this Unit we will concentrate on partnership between the citizens and local administration in the area of ‘civic service delivery.’ The Government participates in the Programme with the officials of its public utility departments, that is the BSES and NDPL, Delhi Jal (Water) Board (DJB), Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD), New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC), Department of Environment and Forest (DOEF), Delhi Development Authority (DDA), and Delhi Police (DP). In the same way the non-state actors, that is the citizens, participate in the Programme through their Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs). These two actors, that is, the government and citizens, participate in solving and improving the civic problems pertaining to conditions of water supply, sewage management, electricity supply, environment sustainability, law and order, etc. jointly. Before we commence on the discussion on the Bhagidari Programme, we will succinctly deal with the need for such a partnership. 10.2 NEED FOR PARTNERSHIP When India became a republic in 1950, it faced the challenges of poverty, increasing population, weak infrastructure, material constraints, poor agriculture sector and impoverished social and economic conditions. The first and foremost task before our leaders was to build the infrastructure for the country and plan for its agricultural development. The entire task was on our political leaders and civil servants. Rather, it was the bureaucracy, which played a crucial role in pushing up the needed development and growth in the post-independence era. But with time, it gained grounds and became a prime power wielder in the political system. With legislature and executive lacking time and expertise, delegated legislation and issuance of necessary directives and guidelines became the function of bureaucracy. It perfected the technique of rule application, rule interpretation and rule adjudication. Because of its permanent tenure, superior merit and knowledge, professional competence, technical know-how and experience and expertise, it got involved in all aspects of the policy cycle. As La Palambora states that with the increasing need and pressures of social and economic development, bureaucracy became unrestrictive especially in the developing nation, where the major decisions involved ‘authoritative rule-making’ and ‘rule-application’ by the government resulting in the emergence of ‘over-powering’ bureaucracies. The need for qualitative accountability and trust was felt as the bureaucratic administration due to its over centralising tendencies, self-centredness and conservatism never took the people along with it in decision-making. Public service delivery became a mundane activity without any involvement of the people. Public servants could not appreciate the need to bring in social values and reasoning in policies. Administration working in citadels had no accessibility to people. Hence, people found them unapproachable and unaccountable. Recent trends of globalisation, privatisation and localisation have necessitated that the administrators shed their elite character and change and improve their rigid behaviour. Instead of being away into self-interests, they have to be now empathisers of people’s problems. Their mindset and attitude has to undergo change. Besides being accountable politically they now have also to be accountable to multi-stakeholders. They have to operate in a transparent fashion. They cannot be operating from citadels and watertight departments anymore. They have to work with people to address the grassroots problems. Likewise, they need to have regular face-to-face interaction with the citizens and involve them in decision-making. It is only then that we can expect the growth of a publicly accountable and trustworthy bureaucracy. A new work culture with citizens’ participation and partnership in governance will help the government and administration to serve the citizens better. In this regard, the partnership initiative of the Delhi Government proves its mettle by rendering a transparent, accountable, participative and decentralised citizen services delivery. In the ensuing sections, we will discuss the Bhagidari Programme being implemented in the NCT of Delhi by the government and the citizens jointly. The discussion will focus on the issue of civic service delivery in the municipal areas of Delhi. 10.3 BHAGIDARI: A PROGRAMME OF GOVERNMENT-CITIZEN PARTNERSHIP In pursuance of the tenets of democratic citizenship, organisational humanism and community participation, the Delhi Government has undertaken a partnership programme with its citizens. The Programme, namely, Bhagidari, meaning partnership, was initiated in the late 99/early 2000 by the Delhi Government to develop partnership, co-sharing and joint stake holding of the citizens and the government in governance. Inspired with Gandhi’s motto of self-governance and decentralisation, it has stemmed from the need to provide a definite role to people in local governance. It is both participative and collaborative with people being treated as equal partners in development. The four basic elements of Bhagidari are: • Partnership and Participation • Governance • Citizens /Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs); and • Public Utility Departments (PUDs) and Civic Service Agencies (CSAs), which impact citizens’ lives most at the day-to-day ground level. These departments and agencies are BSES and NDPL, DJB, MCD, NDMC, DOEF, DDA and DP. It was initiative of the Chief Minister (CM), ‘Sheila Dikshit who started the Bhagidari process of interaction, dialogue, consultation and partnership with the citizens groups to improve the quality of administration and civic life in Delhi. Placed in the Chief Minister’s Office (CMO), a Bhagidari Cell has been created to look into the Programme. The Cell coordinates the activities covered under Bhagidari. The Programme has been decentralised at the level of the nine revenue districts, where it is carried forward by the Deputy Commissioner (DC) Revenue, who is the district co-ordinator. The General Administration Department is the nodal department that provides financial and administrative support. The Asian Centre for Organisation Research and Development (ACORD), a professional body, has been facilitating the entire Bhagidari process. Based on innovative methodologies and processes, the Programme aims to: • create and sustain a sense of ownership, both in citizens’ groups/associations, as well as in PUDs officials; • create and sustain a vision of a clean, green and very liveable Delhi; • bring citizens more actively as partners into the processes of governance, rather than see it typically as a top-down leader-centred effort; • make the whole model and process very interactive, genuinely participative and based on professional social science principles of facilitating and sustaining change in large-systems; and • use real time strategic management- group dynamics- to facilitate change by carefully designing individual and group meetings with multiple stakeholders and identifying issues/agenda around which dialogue and consensus can be built. 10.3.1 Working Process The Bhagidari Cell in the CMO coordinates the entire process of Bhagidari. It monitors and reviews the implementation of the commitments made by the RWAs and the officials of the PUDs in the Large Group Interactive Workshops (LGIWs) on a regular basis. The planning and organising of LGIWs with full responsibility is devolved to each of the nine DC Revenue. They are responsible to organise the workshops in districts coming under their purview. The district officials and area officials are the nodal officers of their district/ area respectively. They participate on behalf of their departments/agencies in the LGIWs representing their respective areas. The working process of the Bhagidari Programme is as follows: • Issue Generation: the Bhagidari process begins with the CM generating a range of issues through questionnaires to the RWAs. The CMO also holds a series of meetings with the representatives of RWAs to obtain information on the issues, which RWAs feels are critical. Meetings are also held with the officials of the PUDs. • Top Team: the issues so identified are discussed in a meeting-cumworkshop by a top team consisting of the CM, Chief Secretary, ministers, all principal secretaries and heads of civic agencies. The aim of the meeting is to crystallise and achieve consensus on the issues. The final list of issues is drawn up in consultation with the facilitating agency, that is, the ACORD. These issues determine the theme and agenda for the ‘design team.’ The top team also ensures the implementation of the solutions and follows up mechanisms for monitoring. • Design Team: the design team takes up the agenda developed by the top team. It prepares the first draft of the design of the LGIW. It consists of 15-20 participants representing the stakeholders participating in the LGIW including the civic agencies and one or two officers from the CM’s office. It is rather a microcosm of the macro-group that will participate at the workshop. The design team workshop, which is of 2-3 days depending on the issues and the participants, opens up the communication channels among the different stakeholders and enhances the energy and enthusiasm of all the groups about the LGIW. This builds a confidence about the possibility of change. The team works out the programme outline and the methodology of the LGIW. It lays down the ‘Theme and Purpose’ for the LGIWs through consensus. The members involve in understanding the LGI process. They choose/advise/recommend a design for the LGIW. All viewpoints are considered before putting together the initial basic design. They design the ‘opening process’, and ‘closing process’ to ensure the participative nature of the LGIW. The team provides the grouping of issues and allows one issue to be discussed by a minimum of 4-5 tables. Hence, four to five issues can be taken up together ensuring all issues are taken up in the available time. In a nutshell, the design team draws a sketch of the LGIW. To provide all the data, facts and information to the LGIWs, the design team takes the responsibility of preparing an information pack for the participants. A small 6-8 member ‘core design team’ is formed from the design team and they take the responsibility of preparing the info-pack. This is collection of technical and financial data, documents, papers, excerpts from journals, reports, etc., which are relevant for the participants of the workshop. The principle underlying is that all participants must start from the same broad database and then add/exchange further information to build-up the common data. The design team workshop creates a strong sense of involvement and ownership and makes the members ambassadors for the LGIW. • Large Group Interactive Workshops: the most important in the entire Bhagidari process is the LGIW. LGIW based on ‘large group dynamics’ and ‘real time strategic change management’ are organised to bring large groups of RWAs and PUD officials together in intensive and participatory dialogue on the theme and purpose given by the design team. It is here that participative, collaborative and solution finding joint action is taken. Each workshop has 200-400 participants (RWAs and officials) seated in a table-wise arrangement. Each table has four citizens of the RWAs, two from one colony, and 5-6 officials of the PUDs and CSAs. Care is taken to seat nodal area officials of PUDs at the table where representatives from citizen groups of their area are sitting. In a workshop around 30-35 such table arrangements are made. The table form of discussion is an example of horizontal decision-making generating public trust and confidence. Operating on the principles of multi-stakeholders collaboration, it secures ‘joint ownership,’ of the citizens and government of the change process. The workshops are of two and a half to three days in duration. On the first day, the design team presents the theme and purpose. At the end of the day, the core design team collects the feedback sheets from the participants, collates the same and presents it before the entire large group on the next day. The same things are undertaken on the second day also. On the third day, the groups undergo experiential learning (subconscious processing for two successive nights), discovering common grounds to work together and taking ownership for solutions. In this multistakeholder workshop ownership of change is experienced and strengthened. The ultimate purpose of coming up with joint solutions to joint problems is served. The principle of feedback loops is followed to help the groups to share the output, suggestions, solutions and strategies. Mobile mikes and charts are used for reporting out agreed solutions and perceptions and displaying all outputs of all table groups. Sufficient time is given for moving around and reading the display of outputs of all groups. Quick typing, photocopying and distribution of all outputs are done. Thus, the whole process works through transparency and feedback. This helps in keeping everyone in the picture and in the process intimately. It energises the table groups and creates a critical mass with a mandate and a momentum for implementing change. It leads to the discovery of common grounds, common interests, common problems, common solutions and a common ownership of the change process. Action teams are set up on the second and third day of the LGIW with an agreed time frame for implementing the agreed solutions. The action teams are constituted from the table groups with a mandate both by the large group itself as well as the senior leadership group. These teams implement the most workable solutions emerging from the LGIW on the basis of the strategies and output by all table groups. • Steering Group: subsequent to the LGIW, the design team is constituted into a steering group. It provides help, assistance and support to all the action teams by removing roadblocks and speaking to the right people for smoothening the implementation. It sustains the change momentum by holding monitoring and review of the implementation on a fortnightly or monthly basis. • Presentation by the CM and the Heads of PUDs/ CSAs: besides the above, on the first day of the LGIW, there is a presentation by the CM and the Heads of PUDs/ CSAs about the current status of Delhi. On the last day also the CM and the HODs respond to queries raised by participants. In this way the basic principle of feedback and response is designed into the process, rather than the usual one-way communication. There is also a ‘case presentation’ of similar initiatives taken up in other states. The CM’s office contacts and invites the presenters. Newsletters, progress reports, recognition for successes and sharing of learning from experiences are used to sustain the momentum, enlarge support bases and encourage networking and collaboration for sustained change. • ACORD: ACORD is the facilitator of the entire Bhagidari process, that is, from the beginning to the end. It works with the design team and prepares the detailed minute-to-minute design and process methodology of every step for the LGIW. The processes provide for designing of the table groups for the LGIW in such a manner that they become self-managing, problem solving and collaborating teams without intervention. Issues related to each official agency are spread over for three days. Guidelines are provided for every session for the table groups to secure a common understanding. According to the number of issues involved and the number of tables in a workshop, the issues are so split so that all groups may discuss different issues. But it is assured that at least 40-50 participants get the opportunity to deliberate on a common issue and generate solutions. This turns out to be fairly representative of what the other groups would have to say, as most table groups have all the stakeholders represented. Besides, it also plans ‘case presentation in good governance,’ and ‘presentation by the CM and the Heads of the PUDs’ for the workshop. Further, it designs and plans the fun-break in the workshop (first two days) to provide entertainment and re-energise the groups. It also designs the feedback system taken at the end of the first and the second day to keep the process transparent. 10.3.2 Implementation, Monitoring and Review After the workshop, the list of solutions is sent to the departments and DC Revenue offices and the CMO. The Principal Secretary to CM issues a letter to the head of the department of each participating PUD/ civic agency for appointing nodal officers, holding monthly meetings with the RWAs and sending monitoring reports to the CMO. The heads of the departments are designated as the chief nodal officers and they in turn designate their district nodal officials to implement the solutions in their district. The district official liaisons with the chief nodal officer and the DC Revenue and also ensures follow up action of his subordinate area nodal officers in the district. The area nodal officers are designated to a group of RWAs. They work under the supervision of the district nodal officers. They hold meetings with the listed RWAs within a span of ten days of the conclusion of the workshop. They work out an action plan in consultation with the RWAs for implementation of solutions and actions decided in the workshop. The action plans are in turn send to the district nodal officers who finalises them in consultation with the chief nodal officers. The plan is then to be implemented within the budgetary provisions for the annual year by the area officials in collaboration with the RWAs. Thereafter, the area nodal officers hold monthly meetings with RWAs for continuous implementation of the action plans. The chief nodal officer may also hold a meeting with the district nodal officers to review the programme as per the action plan in every two months. Besides the above, the DC Revenue of respective districts hold a review meeting with the RWAs and the district nodal officers on the last Friday of every month and send the status report to the CM and the Divisional Commissioner by the 5th of every subsequent month. To give due recognition to the officials for their contribution and involvement, the officials performing a role in the implementation of the Bhagidari Programme have to give an account of his/her participation in the self-appraisal. The reporting and reviewing officers will make a specific mention about the involvement and ability of the officer in implementing the Programme. Significant innovations introduced by him/her are also mentioned. 10.4 REALISING BHAGIDARI Bhagidari takes place in three fold ways. We will be discussing them individually. 10.4.1 Bhagidari between RWAs and PUDs/CSAs The people and the PUDs collaborate with each other to chalk out the ways to carry out the development programmes and facilitate citywide changes. A brief description of the joint activities undertaken by citizen groups and PUDs/ CSAs shows the way partnership is being carried out to address genuine problems and grievances. • DJB The DJB has involved the people’s groups in the process of water conservation and water harvesting. It nominates water wardens and assistant water wardens from the citizen groups and imparts them specialised training to check and rectify water leakage. Problems, such as, replacement of the old and leaking pipes and desilting the sewers are jointly done. Awareness is spread through intensive advertisement campaigns in water saving, water conservation and against using water from hand pumps for drinking purposes. Technical and financial help is provided to the group housing societies and individuals to take up rain water-harvesting projects. Matters pertaining to payment and collection of water bills and internal colony sewage system have been devolved to the RWAs. The problem persisting is taken up again in the workshops. DVB The DVB and its private power distribution companies coordinate with the RWAs in meter reading and handling load shedding and power breakdown. People can get the change in the meter names through RWAs instead of personally coming to the offices. The companies involve the RWAs in replacement of low-tension wires and faulty meters and also in revenue enhancement and its re-investment. Complaint cells operate for the people. The RWAs now are made responsible for prevention of power thefts. If the RWAs are facing some problems they take up in the workshops with the officials. Federation of Indraprastha Extension has arranged for drop boxes in societies to facilitate payment of bills without any hassle. The Dilshad Colony RWA has created facility for collection of electricity bills through drop boxes. The representatives of the RWA attended a seminar on ‘Power and Water Conservation’ through Bhagidari, and has hence educated the residents to adopt conservation measures. • MCD The MCD has decentralised the house tax collection, maintenance of community parks and management of community halls and sanitation services to the RWAs. In cooperation with the RWAs it imposes fine on littering. For maintenance of sanitation it provides sanitary staff to the RWAs. The RWAs oversee the work of the sanitary staff, provide for door-to-door collection of garbage and maintain community bins. They have to supervise the internal colony sewage system and generate public awareness on sanitation. Besides the above, the Municipal Valuation Committee also receives inputs from the RWAs for implementation of the new tax system. • DoEF DoEF in association with the RWAs have taken the onus of creating green belt in the city by planting and maintaining saplings. Anti-plastic and antilittering campaigns with RWAs are organised to persuade the non-use of plastic bags. For this purpose, the Delhi Plastic Bag (Manufacture, Sale and Usage) and Non Biodegradable Garbage (Control) Act 2000 has been made effective from 2nd Oct. 2001. In many colonies programme of waste management has been initiated for segregation of biodegradable and nonbiodegradable waste at the source level and for further recycling. It has taken up the implementation of the ‘Clean Yamuna,’ campaign with the RWAs. • DDA DDA participates with the people in maintaining community parks, preventing encroachments and providing solutions for resettlement. They have also worked out the problem of parking places with the RWAs. Many RWA federations have developed parks with the help of DDA. During monsoon the federations have planted trees and shrubs in their areas. • DP DP involves the RWAs for crime prevention, neighbourhood watch, verification of domestic helps, prevention of encroachments, regulation of traffic through the colonies and prevention of illegal sale of liquor. Many RWAs have installed security system in their colonies in association with the DP. Camps are set up for the purpose of verification of domestic helps in many colonies and a list of senior citizens living in the area is generated by the police from the respective RWAs. 10.4.2 Bhagidari on Complex Policy Issues The Delhi Government has consulted and taken feedback on certain complex policy issues from the RWAs. These issues pertain to: • Electricity meters and billing by DISCOMS (distribution companies) Privatisation of power distribution brought certain problems. There were complaints of high bills and new meters running faster. On feedback from RWAs, the Delhi Electricity Regulatory Commission (DERC) got the new electronic meters re-tested. Deficiencies were reported and the DERC reprimanded the DISCOM concerned and issued orders for installation of new reliable meters. • Water regulatory commission proposal The DJB proposal to set up a water commission made the citizens to worry as this would indicate the start of a process of privatising the supply of drinking water. The RWAs and the RWA federations communicated their concern directly to the CM’s Bhagidari Cell. Taking note of the anxieties of the citizens the CM made a clear and open statement that drinking water supply would not be privatised. • Unit area method of property tax RWAs from across Delhi provided colony wise information and feedback to the MCD on several parameters of categorisation of colonies, such as quality of infrastructure and level of civic services. The MCD was able to utilise this feedback to update its own database and make amendments to the categorisation of colonies as well as fine tune the unit area method as a system of self-assessment of property tax. • Auto-fare revision The Delhi Government sought the views, feedback and suggestions of the RWAs and RWA federations on this issue. The rate revision for the autos was worked out and agreed, reflecting a new balance of moderation between the key stakeholders- the citizens, the auto-unions and the Transport Ministry of the Government. These kinds of involvement helped the RWAs to evolve as a communication channel between the citizens and the government, policy impact anticipator for proposed policy matters on the lines of citizens and generator of suggestions and alternatives with the aim to fine-tune important schemes and changes. This has transformed the citizen groups as policy partners owing to their detailed knowledge of local conditions and community perceptions and of the anticipatory impact of proposed policies and schemes. 10.4.3 Internal Bhagidari for Change Management The PUDs have used the process of Bhagidari to bring about change management in their internal organisation working. The DJB undertook a pilot project to bring about changes at all levels and functions within the organisation along with its consumer-stakeholders. The following steps were followed in the change management project: Step l- confidential one-to-one meetings were held with CEO, Top Management Team and officers and staff/ unions and associations. This helped in understanding their perceptions on success factors, strengths and weaknesses and consumer needs. This was followed by a written questionnaire to one thousand employees at all levels and functions to understand their perceptions on strengths, weaknesses, gaps and the environment (internal and external) of the organisation. Step ll- the feedback from one-to-one meetings and questionnaires were compiled and put together for consideration by the Top Team consisting of senior most members including members of the Board. Step lll- ACORD conducted the one-day ‘Top Team Workshop’ in which 17 senior representatives of DJB participated. It identified six major change goals to be focused by the LGIE workshop. The six goals pertained to improving customer satisfaction, water quantity augmentation and supply improvement, reducing water pollution, increasing revenue, and cost reduction and improvement in efficiency, productivity, transparency, integrity and accountability. Step lV- ACORD conducted a two-day Design Team Workshop for a group consisting of one member from the Top Team and 17 participants from a crosssection representing all departments and all levels of DJB. Based on the agenda of the Top Team, programme outline of the LGIE was designed with a theme-‘DJBBe Every Customer’s Delight’, and a purpose-‘To Reach the Flow of Clean Water to Every Household’. The representatives of various concerned stakeholders of DJB to be involved in the LGIW were finalised and the major issues to be incorporated during the Workshop were discussed. The major points to be kept in mind while finalising the list of participants as well as the table grouping were discussed to ensure that all functions and all levels of DJB are represented along with external stakeholders on each of the tables. The change-management process through the large group dynamics with the citizens has helped them to go into and inside civic agencies including all levels from Commissioner to area level officials. This has devolved the internal change management with large civic organisations and helped them to become citizensatisfaction-centric. It has also helped in upgrading system capability and performance standards of service delivery. 10.5 CRITICAL SUCCESS GAPS For the Bhagidari to be successful at the ground level, certain critical factors have to be paid attention: • The most important task is to manage the change process. There is resistance to change from some and some are willing to accept. It took time to convince the citizens about partnership in which they had to contribute as much as the government officials. That they can now have another avenue for redressal of grievances and they are the owners of the Programme and that they are stakeholders in the development of the city is taking time to get entrenched. • The people’s representatives such as Members of Legislative Assembly and the Municipal Councillors are not participants in the entire process. If they are involved, they will have a feeling of ownership towards it. • Bringing together a large number of citizens groups and government officials on a common platform is not an easy task. It requires detailed planning and coordinated action for holding preliminary meetings, interactions and whole gamut of logistical arrangements. • A Mid-Term Impact Assessment was done by ACORD. The assessment has indicated that people have by and large appreciated the Programme but the government officials are required to be sensitised further. There is resistance from the field level government officers who are not willing to step out of their bureaucratic shell and embrace the direct interaction with citizen groups. They feel it is erosion of their authority. • The RWAs felt that the response from the junior officers was not as good as by the seniors. Certain agencies like PWD are not present in the workshops. Few officials turn up for the meetings and some departments are not at all represented. Also, due to the inter-departmental jurisdictions (DDA, MCD, NDMC, Cantonment Boards) the problem of bad roads, drains and sewer is not getting solved. • The officials perceive that bureaucratic procedures and financial constraints need to be reduced/eliminated. Some of them felt that some issues required policy-change and was hence beyond their purview. They found that the RWAs are not coming forward to identify and educate the people, for example, in the use of water meters. Plantation takes place but follow up is done consistently. • Bhagidari has so far been with registered associations. The challenge is now step out with the Programme into slum clusters, resettlement colonies and unauthorised areas. The high rate of migration and growth of slums on a continuous basis and an alienated and aggressive city culture adds to the challenge. • Right now the Government provides all resources and does all the monitoring and management. It now faces the challenge of mobilising private sector participation for financial and expert systems; and • There is need for institutionalisation of the Bhagidari model. The process is at a critical stage and citizen groups’ expectations are high. There is a clear need for careful institutionalisation, structural and legal evolution and a balanced empowerment. A good institutional framework is needed so that citizens’ partnership in good governance becomes a permanent part of the structure and processes. Even this process of further evolution and institutionalisation has to be consultative and participative. Inclusiveness and participation has to extend to those who are not yet involved in the process. There has to be a clear form and structure based on functional and organisational logic. The officials perceived that the process should be institutionalised so that it continues regardless of individuals in the leadership positions. 10.6 BHAGIDARI: A MODEL OF GOOD GOVERNANCE Despite the above-mentioned limitations Bhagidari can be termed as a model of good governance. It is most consistent and relevant in the present realm of democratic governance. It attempts to go beyond the norms and practices of the traditional administration and gives a new meaning to the present day governance. • The interaction through face-to-face dialogue has brought a paradigm shift in the way governance was perceived. Traditionally, interaction was just the grievance expression and grievance handling. But Bhagidari has brought a shift in this paradigm to a relationship where both the citizens and the officials identify the solutions to the issues of common concern, work together to implement the agreed solutions and improve the quality of life. Most of the participants feel that it has reduced the feeling of helplessness. They now have a feeling, ‘we can find and implement solutions together with government’. Bhagidari has set a base for a good relationship between the citizens and officials. • In the Workshops based on Large Group Dynamics for Strategic Change, each RWA along with local area officials focus on live priorities and problems and solutions appropriate to local conditions are discussed, agreed and implemented upon. There is achievement of common ground even when stakeholders come from different mindsets and adversarial positions. This sets room where diverse views can be vent. Over 3000 concrete solutions were implemented within months of each workshop in the first four years. Thus the time taken for solution-implementation becomes minimal. It has reduced unnecessary delays, red-tapism and corruption in administration. • The office bearers of the citizen groups have been issued ID cards. This has empowered the Bhagidar citizen groups and legitimised their role in sustaining partnership. This has helped in building a feeling of ownership among the citizens as well as the government officials. • The Right to Information is a giant step taken. The officials have to give all relevant information pertaining to their department/agencies to the RWAs. This has increased accessibility and transparency. Also, officials are not operating in a centralised fashion. They are devolving duties to the RWAs and are sharing forums with them in problem solving. All this has ensconced faith in the administration. • RWAs have come forward voluntarily to share responsibilities. They are networking with other RWAs and bringing out newsletters- ‘Bhagidari Masik Patrika’. Hence, with network management there is more cooperation and coordination in finding and implementing solutions. This has changed the old adversarial relationship. A cooperative partnership has taken shape with greater accessibility. Actual solutions and real working out has become possible. • The Department of Personnel and Training, Government of India has introduced performance appraisal for all officers of the Delhi Government on their specific contributions during each year towards sustaining Bhagidari in the form of citizen-centric administration. This has institutionalised Bhagidari concept in the civil service. This has ensured accountability in solving problems and sustained interest of officials in the partnership scheme to implement the solutions. • This mechanism of feedback and review meetings held by the CMO with the RWAs and PUDs has given the citizens an access to the CMO and to Heads of Departments. This has made the RWAs feel empowered and they have become ready to take on the responsibility of checking, overseeing and monitoring the departments/agencies. This has created accountability and transparency. Bhagidari has given a voice to the citizens on the issues that concern and affect them and hold the utility/civic agencies accountable for their actions. On the other hand, RWAs have become sensitive to the problems of the utility/civic agencies and have started offering help and suggestions to their field level officials; and • RWAs and the RWA Federations are live examples and models of community and civil society. They join the Programme voluntarily thinking in terms of the larger public interests. The LGIWs are the forums to provide dialogue and discourse among the administrators and the people. It is here that the citizen groups meet the officials face-to-face and interact. The problems are sorted out, solutions are agreed upon jointly and both work together to implement them. This has made horizontal decision making possible. 10.7 CONCLUSION Bhagidari model, where there is a constant positive pressure building up from the top by the HOD’s and CMO and by the RWAs from the bottom, is building a positive pressure on the utility/civic agencies to perform and show results. The RWAs have also started taking responsibility for implementing the action points. With RWAs participating the people now have faith and trust in the government. Bhagidari has helped the PUDs and the CSAs in solving the day-to-day problems of the people on one hand and on the other it has provided help to them in maintenance and upgradation of services. It has also made them to adhere to democratic and professional values. This has enabled a non-partisan approach in their attitude and functioning. Models like Bhagidari can be replicated in developing countries to improve governance. This Model can secure accountability, trust and transparency and rebuild an effective and responsible administrative culture. For this purpose, there is need to engage the citizens and communities to partner with the government for collective action. Hence, there is need: • to build communities; • to have government encouragement and political will to reach out to the communities and citizens; • to have democratic forums at the ground level for participative and collective action; • to educate citizens in collaborative and participative governance; • to have self-inclined and motivated communities; and • to sensitise administrators and provide incentives and assurances to them. 10.8 KEY CONCEPT Bhagidari (Hindi Term): Partnership Bhagidar (Hindi Term): Partner Divisional Commissioner: Administrative head of division having districts under them. Deputy Commissioner: Administrative head of the district (Revenue). Area Officials: They are officials below the Sub-Division Officers (SDOs) and are of the rank of Block Officials. Large Group Dynamics: Processes and techniques utilised by social scientists and organisational consultants to facilitate community change, or organisation change. 10.9 REFERENCES AND FURTHER READINGS • Reports, Bhagidari The Citizen-Government Partnership, Government of NCT of Delhi • King, C., S., and C., Stivers, 1998, Government is Us: Public Administration in an Anti-Government Era, Thousand Oaks, Sage, CA • Vinzant, J., and L., Crothers, 1998, Street-Level Leadership: Discretion and Legitimacy in Frontline Public Service, Georgetown University Press, Washington DC • Terry, L., D., 1993, Why We Should Abandon the Misconceived Quest to Reconcile Public Entrepreneurship with Democracy, PAR, 53(4) • Denhardt, J., V., and R., B., Denhardt, 2003, The New Public Service Serving, Not Steering, M., E., Sharpe, Armonk • Barry, Hindness, Representative Government and Participatory Democracy, in Andrew Vandenberg, ed., 2000, Citizenship and Democracy in a Global Era, Macmillan Press Ltd., Houndmills • Vigoda, Eran, From Responsiveness to Collaboration: Governance, Citizens and the Next Generation of Public Administration, in PAR, Sept/ Oct., 2002, Vol.62, No.5 10.10 ACTIVITIE 1) Explain the need of partnership between the government and citizens at the local levels. 2) Do you see Bhagidari programme of the Government of Delhi reflects the partnership between government and citizens at the local level?