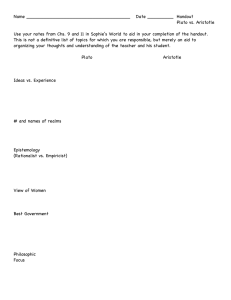

Lesson 3 Functions and Philosophical Perspectives on Art Learning Outcomes By the end of this lesson, students should be able to: 1.distinguish between directly functional and indirectly functional art; 2.explain and discuss the basic philosophical perspectives on the art; 3.realize the function of some art forms in daily life; and 4.apply concepts and theories on beauty and aesthetics in real life scenarios. Functions of Art When it comes to function, different art forms come with distinctive functions. There is no one – to – one correspondence between an art and its function. Some art forms are more functional than others. Personal (public display or expression) The personal functions of art are varied and highly subjective. This means that its functions depend on the person – the artist who created the art. An artist may create an art out of the need for self – expression. This is the case for an artist who needs to communicate an idea to his audience. It can also be mere entertainment for his intended audience. Social Functions of Art Art is considered to have a social function if and when it addresses a particular collective interest as opposed to a personal interest. Political art is very common example of an art with a social function. Art may convey message of protest, contestation, or whatever message the artist intends his work to carry. Physical (utilitarian) The physical functions art can be found in artworks that are crafted in order to serve some physical purpose. Other Functions of Art Religious Function – or liturgical art, music, or drama is used as part of the ritual of a given religion. Cultural Function- Through the printed matter, art transmits and preserves skills and knowledge from one generation to another. It broadens one’s cultural background and makes man more civilized and his life more enduring and satisfying. Philosophical Perspectives of Art Art as Imitation Plato in his masterpiece, The Republic, particularly paints a picture of the artists as imitators and art as mere imitation. In his description of the ideal republic, Plato advises against the inclusion of art as a subject in the curriculum and the banning of artists in the Republic. In Plato's metaphysics or view of reality, the things of this world are mere copies of the original, the eternal, and the true entities that can only be found in the world of forms. Human beings endeavor to reach the forms all throughout this life, starting with formal education in school. Plato was deeply suspicious of arts and artists for two reasons: they appeal to the emotion rather than the rational faculty of men and they imitate rather than lead one to reality. Plato is critical of the effects of art, specifically poetry to the people of the ideal state. Poetry rouses emotions and feelings and thus, clouds the rationality of people. Poetry has a capacity to sway minds without taking into consideration the use of proper reason. As such, it leads one further away from the cultivation of the intellect that Plato campaigned for. Likewise, Socrates is worried that art objects only represents the things of this world., copies themselves of reality. As such, in the Dialogue, Socrates claimed that is just an imitation of an imitation. A painting is just an imitation of nature, which is also just an imitation of reality the world of forms. The arts are to be banished, alongside the practitioners, so that the attitudes and actions of the members of the Republic will not be corrupted by the influence of the arts. For Plato, art is dangerous it provides a petty replacement for the real entities that can only be attained through reason. Art as Representation Aristotle, Plato's most important student in philosophy, agreed with his teacher that art is a form of imitation. However, in contrast to the disgust that his master holds for art, Aristotle considered art as an aid to philosophy in revealing truth. The kind of imitation that art does is not antithetical to the reaching of fundamental truths in the world. Talking about tragedies for example, Aristotle in the Poetics claimed that poetry is a literary representation in general. Akin to other art forms, poetry only admits of an attempt to represent what things might be. For Aristotle, all kinds of art including poetry, music, dance, painting, and sculpture do not aim to represent reality as it is. What art endeavors to do is to provide a vision of what might be or the myriad possibilities in reality. Unlike Plato who thought of art as imitation, Aristotle conceived art as representing possible versions of reality. In Aristotelian worldview, art serves two particular purposes. First, art allows for the experience of pleasure. Experiences that are otherwise repugnant can become entertaining in art. For example, a horrible experience can be made an object of humor in a comedy. Secondly, it also has the ability to be instructive and teach its audience things about life; thus, it is cognitive as well. Greek plays are usually of this nature. Art as Disinterested Judgement In the third critique that Immanuel Kant wrote, the Critique of Pure Judgement, Kant considered the judgement of beauty, the cornerstone of art, as something that can be universal despite its subjectivity. Kant mentioned that judgement of beauty, and therefore, art, is innately autonomous from specific interests. It is the form of art that is adjudged by one who perceives art to be beautiful or more so, sublime. Therefore, even aesthetic judgement for Kant is a cognitive activity. Kant recognized that judgement of beauty is subjective. However, Kant advanced the proposition that even subjective judgments are based on some universal criterion for the said judgement. In the process, Kant responded to the age-old question of how and in what sense can a judgement of beauty, which ordinarily is considered to be subjective feeling, be considered objective or universal. How is this so? For Kant, when one judges a particular painting as beautiful, one in effect is saying that the said painting has induced a particular feeling of satisfaction from him and that he expects the painting to rouse the same feeling from anyone. There is something in the work of art that makes it capable of inciting the same feeling of pleasure or satisfaction from any perceiver, regardless of his condition. For Kant, every human being after perception and free play of his faculties, should recognize the beauty that is inherent in a work of art. This is the kind of universality that a judgement of beauty is assumed by Kant to have. So when the same person says that something is beautiful, he does not just believe that the thing is beautiful for him, but in a sense, expects that the same thing should put everyone in awe. Art as Communication of Emotion The author of War and Peace and Anna Karenina, Leo Tolstoy, provided another perspective on what art is. In his book, What is Art, Tolstoy defended the production of the sometimes truly extravagant art, like operas, despite extreme poverty in the world. For him, art plays a huge role in communication to its audience emotions that the artist previously experienced. Art then serves as a language, a communication device that articulates feelings and emotions that are otherwise unavailable to the audience. In the same way that language communicates information to other people, art communicates emotions. In listening to music, in watching opera, and in reading poems, the audience is at the receiving end of the artist communicating his feelings and emotions. Tolstoy is fighting for the social dimension of art. As a purveyor of man's innermost feelings and thoughts, art is given a unique opportunity to serve as a mechanism for social unity. Art is central to man's existence because it makes feelings and emotions accessible to anyone in varied time and location, art serves as a mechanism of cohesion for everyone. Thus, even at present, one can commune with early Cambodians and their struggles by visiting the Angkor Wat or can definitely feel for the early royalties of different Korean dynasties by watching Korean dramas. Art is what allows for these possibilities. Reference: (From the book, Art Appreciation by Caslib, Garing & Casaul)