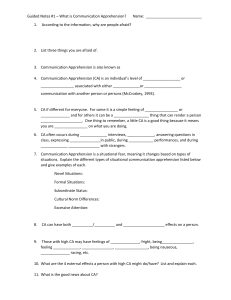

Learning and Instruction 33 (2014) 1e11 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Learning and Instruction journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/learninstruc Do students’ beliefs about writing relate to their writing self-efficacy, apprehension, and performance? Joanne Sanders-Reio a, *, Patricia A. Alexander b, Thomas G. Reio, Jr. a, Isadore Newman a a b College of Education, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199, USA College of Education, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Received 12 September 2012 Received in revised form 9 February 2014 Accepted 14 February 2014 Available online 18 March 2014 This study tested a model in which beliefs about writing, writing self-efficacy, and writing apprehension predict writing performance. The Beliefs About Writing Survey, the Writing Self-Efficacy Index, and the modified Writing Apprehension Test were administered to 738 undergraduates to predict their grade on a class paper. In a hierarchical regression, beliefs about writing predicted variance in writing scores beyond that accounted for by writing self-efficacy and apprehension. Audience Orientation, a new belief associated with expert practice, was the strongest positive predictor of the students’ grade. Transmission, a belief in relying on material published by authorities, was the leading negative predictor. Writing selfefficacy predicted performance, albeit modestly. The traditional measure of writing apprehension (anxiety about being critiqued) was not significant, but Apprehension About Grammar, a new construct, significantly and negatively predicted performance. These results support the possibility that beliefs about writing could be a leverage point for teaching students to write. Ó 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Writing self-efficacy Writing apprehension Beliefs about writing Expertise Writing development 1. Introduction Social cognitive theory established the importance of beliefs in human learning and performance. The most important of these beliefs are self-efficacy beliefs, one’s confidence in one’s ability to perform tasks required to cope with situations and achieve specific goals. People with high self-efficacy are more likely to take on challenges, try harder, and persist longer than those with low selfefficacy (Bandura, 1989). People with high self-efficacy tend to be less apprehensive and to confront anxiety-producing situations to reduce their threat, while those with low self-efficacy avoid such situations (Pajares, 1997). Bandura maintains that there are four sources of self-efficacy, with the most influential being one’s previous successes and mastery experiences (Bandura, 1997). Thirty years of research with students ranging from fourth graders to undergraduates supports the linkages between selfefficacy, apprehension, and performance with respect to writing. Students with high writing self-efficacy write better and are less apprehensive about writing than those with low writing self- * Corresponding author. Tel.: þ1 305 348 0124; fax: þ1 305 348 1515. E-mail addresses: jsanders@fiu.edu, sandersreio@netscape.net (J. Sanders-Reio), palexander662@gmail.com (P.A. Alexander), reiot@fiu.edu (T.G. Reio), newmani@ fiu.edu (I. Newman). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.02.001 0959-4752/Ó 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. efficacy (e.g., McCarthy, Meier, & Rinderer, 1985; Pajares & Valiante, 1999). Correlations between writing self-efficacy and writing performance have ranged from .03 (Pajares & Johnson, 1994) to .83 (Schunk & Swartz, 1993), clustering around .35, while correlations between writing performance and writing apprehension have ranged from .28 (Meier, McCarthy, & Schmeck, 1984) to .57 (Pajares & Johnson, 1994). 1.1. Beliefs about writing More recent work has extended the social cognitive view of writing by exploring whether another type of belief, beliefs about writing, also relates to writing performance and its established correlates, writing self-efficacy and apprehension. In contrast to writing self-efficacy beliefs (i.e., one’s beliefs about one’s own writing skills), beliefs about writing address what good writing is and what good writers do. As Graham, Schwartz, and MacArthur (1993) wrote, “The knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs that students hold about writing play an important part in determining how the composing process is carried out and what the eventual shape of the written product will be” (p. 246). Mateos et al. (2010) similarly described these beliefs as “filters leading students to represent the task of.writing to themselves in a particular way,” with the various models of writing created by these beliefs leading to “different engagement patterns” (p. 284). 2 J. Sanders-Reio et al. / Learning and Instruction 33 (2014) 1e11 Scholars of both educational psychology and writing and rhetoric have studied beliefs about writing. Palmquist and Young (1992) conducted one of the first empirical studies of these beliefs, an examination of the belief that writing is an innate gift that some have and others lack. Overall, undergraduates who believed that writing ability is innate were more apprehensive about writing, had lower estimates of their writing skills and abilities (a belief akin to self-efficacy), and were less confident in their potential to become good writers. The authors concluded that the belief in innateness “appears to make an important, though largely unacknowledged, contribution to a constellation of expectations, attitudes, and beliefs that influence the ways in which students approach writing” (p. 159). More specifically, the authors found an interaction between self-appraisals and apprehension, and the belief in innateness. Among students who had low assessments of their own writing, the belief in the innateness of writing ability strongly correlated with writing apprehension, while among students with high appraisals of their own writing, the belief in innateness did not relate to apprehension. The authors suggested that students with low assessments of their written work and high writing apprehension might use the belief in innateness to rationalize their poor performance. Silva and Nicholls (1993) studied the beliefs underlying six traditions of teaching writing: those emphasizing (a) personal involvement, (b) writing for understanding, (c) mechanical correctness, (d) collaboration, (e) cognitive strategies, and (f) models of good writing. The authors developed two genre-neutral scales, one based on the characteristics of good writing espoused by each tradition and the other reflecting the writing strategies that emerged from each perspective. A principal components analysis (PCA) of each scale, followed by a second-order PCA of the resulting components, yielded four emphases: (a) personal meaning and enjoyment of words, (b) a recursive approach fostering understanding, (c) focus on audience and strategies, and (d) surface correctness and form. Lavelle (1993) published a number of studies about students’ approaches to writing, a broad construct encompassing beliefs about writing, writing self-efficacy, writing goals, and writing strategies. A factor analysis of college students’ survey responses yielded five approaches that fell into two categories, deep and surface. The deep approaches included the elaborationist approach, characterized by personal and emotional involvement, and the relative-revisionist approach, with its strong audience awareness and in-depth revision. The surface approaches were the low selfefficacy approach, with its relative lack of writing strategies; the spontaneous-impulsive approach, characterized by a one-step process and lack of personal meaning; and the procedural approach, with its reliance on strategies. Writers using deep approaches had a stronger sense of audience and revised more, both globally and locally. Those using surface approaches were less invested in their writing, used fewer writing strategies, and were less aware of their audience and writing process. 1.1.1. Transaction and Transmission White and Bruning (2005) explored whether two established beliefs about reading, Transaction and Transmission (Schraw & Bruning, 1996, 1999), influence students’ writing. Writers with high Transaction beliefs are emotionally and cognitively engaged in their writing process. They see writing as a means of deepening their understanding of the concepts they write about and their own views. By contrast, those with high Transmission beliefs regard writing as a means for reporting what authorities think. These writers stick to the information and arguments they find in established sources. Transaction and Transmission are independent of one another, so individuals can espouse neither, one, or both of these beliefs. Students with high Transaction beliefs earned significantly higher grades for their written work, while those with high Transmission beliefs received significantly lower scores. Transaction positively correlated with writing self-efficacy, but did not relate to writing apprehension. Transmission related to neither self-efficacy nor apprehension. The authors suggested that these beliefs influence writing performance via affective (e.g., apprehension), cognitive and behavioral writing processes. Mateos et al. (2010) extended White and Bruning’s (2005) work by studying writers’ adherence to Transaction and Transmission beliefs along with their support of the epistemic beliefs examined by Schommer-Aikins (2004). As in the White and Bruning (2005) study, Transaction positively correlated with academic achievement, while Transmission negatively related to achievement. Additionally, Transaction negatively related to Fixed Ability (intelligence is defined, not malleable), Simple Knowledge (knowledge is comprised of discrete facts, not complex, conceptual structures), and Quick Learning (learning occurs immediately or not at all). Transmission positively related to Simple Knowledge. 1.1.2. Kellogg’s model of writing development The development of the four-factor beliefs about writing framework presented here was guided by Kellogg’s (2008) cognitive model of writing development. Kellogg built on Bereiter and Scardamalia’s (1987) two-stage developmental model of Knowledge Telling and Knowledge Transforming. Knowledge Tellers record what they know about a topic, primarily as their ideas occur to them. Knowledge Transformers are aware of discrepancies between what they intend to write and what their text actually says. These writers revise to bridge these gaps, and they refine their understandings and rethink their ideas as they work. Kellogg added a third stage, Knowledge Crafting, which describes expert writing. Knowledge Crafters tailor their writing to an audience they have richly represented in their minds. They select which information to include and decide how to present it with this audience in mind. A major difference between the writers in these three stages is the number of perspectives and representations they maintain as they write. Knowledge Tellers have one main perspective, their own representation of the text, and only a tenuous grasp of what their paper actually says. Knowledge Transformers consider two perspectives, their ideal text and their actual manuscript; they revise to make their paper more like their ideal representation. Knowledge Crafters juggle three rich and stable representations of their work: their ideal paper, the text as it actually reads, and the text as they think their readers will understand it. Writers in this final stage regulate themselves cognitively, emotionally, and behaviorally. Writers move from one stage to the next only after many of their writing skills have become fluid and their ability to represent their text, in its ideal and actual forms, well developed and stable. Because of the heavy demands writing makes on working memory, particularly central executive function, Kellogg (2008) estimated that it takes writers about 10 years to master each of the first two stages. Only experts and those who write extensively reach stage three, and normally not before adulthood. Even then, they usually write at this level in only a few genres. Because the oldest students that Bereiter and Scardamalia (1987) studied were undergraduates, Kellogg reasoned that most of them were in the first two stages because they would not have had the time to gain stable executive control over the skills associated with stage three. Although Kellogg (2008) clearly delineated these stages, he did not cast them as discrete. Rather, he described writing skills and representations as being on a continuum. He allowed that writers in the first stage may have some conception of their audience and their actual text, but maintained that such representations are J. Sanders-Reio et al. / Learning and Instruction 33 (2014) 1e11 sketchy and unstable. Scheuer, de la Cruz, Pozo, Huarte, and Sola’s (2006) study of children’s conceptions of the writing process supports Kellogg’s views. The Scheuer group examined the conceptions that kindergarteners, first graders, and 4th graders have about writing and thinking at four points in the writing process: before writing, and during writing, revising, and rereading. At each higher grade, the children had a more complex working conception of writing. The kindergarteners worked to capture oral language on paper, while the 4th graders worked to elaborate on and organize their papers so they made sense, were thematically unified, and complied with writing conventions. The older children had more executive control and thought more as they wrote. 1.1.3. The importance of audience Researchers and experts from numerous disciplines concur with Kellogg’s emphasis on audience. In the research on beliefs about writing discussed above, one of the four components generated by Silva and Nicholls’s (1993) secondary PCA stressed the writers’ rapport with their audience. Similarly, one of the main differences between writers who used deep approaches and those who used surface approaches in Lavelle’s (1993) studies was that those who used deep approaches had a stronger sense of audience. Elsewhere, Beach and Friedrich (2006), and Miller and Charney (2008) discussed how writers adjust the presentation, content, and tone of their arguments in response to their audience and whether this audience is part of the writers’ usual discourse community. Finally, with regard to instruction, writing teachers have emphasized rhetoric, the study of how to influence and persuade readers, since the time of Aristotle (Miller & Charney, 2008). 1.1.4. Writing as a recursive process Scholars and practitioners also agree that proficient writers use a recursive process. Silva and Nicholls’s (1993) secondary PCA yielded a component that emphasized an iterative approach to writing. Lavelle (1993) found that deep approaches involved indepth revision. Iteration is also foundational to Hayes and Flower’s (e.g., 1980) process writing model. Similarly, renowned journalists/writing teachers William Zinsser and Donald Murray stress the recursive nature of writing. Zinsser (1976), whose On Writing Well has sold well over a million copies, maintained, “Rewriting is the essence of writing” (p. 4), while Murray (1991) declared, “Writing is rewriting” (p. vii). 1.1.5. Examining these beliefs about writing in light of Kellogg’s model With respect to Kellogg’s model (2008), White and Bruning’s (2005) Transmission (i.e., the purpose of writing is to convey information published by authorities) can be seen as a form of stage one, Knowledge Telling, as writers inform readers about what authorities have written in sources such as textbooks, encyclopedias, and journals without necessarily engaging with the material or incorporating their own insights and analyses. Transaction (i.e., writers are cognitively and emotionally engaged in their writing and think through their views as they write) aligns with stage two, Knowledge Transforming, where writers work to make their actual papers more in accord with their goals for their papers and their mental representations of the content. Recursive Process, the belief that accomplished writers go through multiple versions of their plans and drafts, also falls under the second stage, where writers rework their papers to refine their understandings and their presentation of those understandings. Audience Orientation, which holds that writers should adapt their writing to the needs of their readers, aligns with Kellogg’s third stage, Knowledge Crafting, which emphasizes audience. 3 1.2. Writing self-efficacy and writing apprehension The earliest writing self-efficacy scales emphasized mechanical writing skills (e.g., Meier et al., 1984). Subsequent measures also addressed substantive writing skills (e.g., Pajares & Valiante, 1999) and writing self-regulation (Zimmerman & Bandura, 1994). This investigation examines all three types of writing self-efficacy. Daly and Miller (1975) operationalized writing apprehension as avoidance of writing and the expectation of negative evaluations of one’s written work. In the Pajares group’s (e.g., Pajares & Valiante, 1997) path analyses, writing self-efficacy directly and positively predicted writing performance, and indirectly contributed to students’ writing scores by reducing and even nullifying writing apprehension as defined by Daly and Miller (1975). However, Smith, Cheville, and Hillocks (2006) suggested that there may be another type of writing apprehension, a fear of making mechanical errors such as spelling and grammar mistakes. 1.3. Purpose of the study, research questions, and hypotheses This study builds on the work of researchers of educational psychology, writing and rhetoric, and expert practice to examine a model of how beliefs about writing, writing self-efficacy, writing apprehension, and writing performance relate to one another. In so doing, it augments White and Bruning’s (2005) work by examining two new beliefs about writing, Recursive Process and Audience Orientation, in addition to Transaction and Transmission. This study also combines and expands existing measures of writing selfefficacy to create a three-component scale that assesses selfefficacy for substantive writing issues, writing mechanics, and writing self-regulation. Finally, the study operationalizes writing apprehension more broadly than do existing studies by investigating apprehension about grammar and correctness as well as avoidance of writing and anxiety about having one’s written work evaluated. The following research questions guided the study: 1. What are the relations among beliefs about writing, writing selfefficacy, writing apprehension, and writing performance? 2. What are the unique contributions of beliefs about writing, writing self-efficacy, and writing apprehension to writing performance? In developing our conceptual model, we were guided first by researchers (e.g., White & Bruning, 2005) who suggested that students’ beliefs about writing influence their writing process, which would include their selection of writing strategies. Thus, it seems, for example, that students who believe that writing is a recursive process would be more likely to proofread and revise their work and to attend to instruction on revision, thereby sharpening their editing skills. Proofreading and revising would in turn improve writing performance, thereby creating the mastery experiences that, according to Bandura (1997), enhance self-efficacy. An exception might occur with maladaptive beliefs, such as the belief that writing is an innate gift, which are associated with weak writing performance. Such maladaptive beliefs may operate in a different way, as rationalizations for poor writing performance, as Palmquist and Young (1992) suggested. With respect to selfefficacy, we were informed by Lavelle (1993), who found that students with low writing self-efficacy reported that they used few writing strategies. We thus reasoned that a belief in the helpfulness of effective writing strategies would precede the development of writing self-efficacy. Finally, for apprehension, we were informed by the Pajares group’s path-analytic research (e.g., Pajares & Johnson, 1994), which indicated that writing self-efficacy often 4 J. Sanders-Reio et al. / Learning and Instruction 33 (2014) 1e11 nullifies the effects of writing apprehension. In sum, we saw beliefs about writing as affecting writing self-efficacy, and self-efficacy as affecting apprehension. For the first research question, based on the extant literature, we predicted that three beliefs about writing, Transaction, Recursive Process, and Audience Orientation, would relate significantly and positively to writing self-efficacy (Hypothesis 1a) and writing performance (Hypothesis 1b), and relate negatively to writing apprehension (Hypothesis 1c). By contrast, we expected the fourth belief, Transmission, to relate negatively to writing self-efficacy (Hypothesis 1d) and writing performance (Hypothesis 1e) and relate positively to writing apprehension (Hypothesis 1f). We hypothesized that all three types of writing self-efficacy would positively relate to writing performance (Hypothesis 1g) and negatively relate to writing apprehension (Hypothesis 1h). Finally, we predicted that both types of writing apprehension would negatively relate to writing performance (Hypothesis 1i). For the second research question, we expected Transaction, Recursive Process, and Audience Orientation to significantly and positively predict writing performance (Hypothesis 2a) but that Transmission would negatively predict writing performance (Hypothesis 2b). We further hypothesized that all three types of writing self-efficacy would positively predict writing performance (Hypothesis 2c) while both writing apprehension subscales would predict negative variance in writing performance (Hypothesis 2d). Finally, we predicted that the beliefs about writing would explain variance in writing performance above and beyond that accounted for by writing self-efficacy and apprehension (Hypothesis 2e). 2. Method 2.1. Participants The participants were 738 undergraduates at a large, researchintensive, Hispanic-serving, public university in south Florida. This study focused on undergraduates because they receive considerable instruction and practice in writing and because using undergraduates facilitates comparison with previous research (e.g., Zimmerman & Bandura, 1994). The students were enrolled in an educational psychology class preservice teachers must take. Most (86%) were women; 68% were Hispanic, 16% were white, 11% were black, and 2% were Asian. Most were juniors (68%) or seniors (24%). With respect to their parents’ education, 88% of the participants’ fathers and 91% of their mothers graduated from high school, 32% of their fathers and 32% of their mothers earned a bachelor’s degree, and 14% of their fathers and 13% of their mothers held an advanced degree. On the other hand, 7% of the participants’ fathers and 5% of their mothers had an 8th grade education or less. More than 37% reported that their first language was Spanish, 31% English, and 3% another language; 28% said they were raised bilingually. 2.2.2. Modified Writing Apprehension Test Daly and Miller’s (1975) Writing Apprehension Test (WAT), a 5point Likert scale, was used to facilitate comparison with previous research. Daly and Miller saw the WAT as assessing polar aspects of a single factor. Other researchers (e.g., Bline, Lowe, Meixner, Nouri, & Pearce, 2001) saw this measure as having two subscales, fear and avoidance of having one’s written work evaluated, and enjoyment in sharing one’s written work with others. These subscales are often called “Dislike of Writing” and “Enjoyment of Writing,” and have 13 items each. Reliability estimates have been consistently greater than .9 (e.g., Bline et al., 2001). Based on the experiences of Smith et al. (2006), we added three items to the WAT to assess apprehension about making errors with respect to grammar, punctuation, and spelling (I worry that I may make a grammatical error; I’m afraid that I will make a punctuation error; I’m afraid that I may miss a misspelled word or typo.) The entire modified scale has 29 items. 2.2.3. Beliefs About Writing Survey Beliefs about writing were assessed with four subscales (Audience Orientation, Recursive Process, Transaction, and Transmission, 50 items) of the Beliefs About Writing Survey, a 5-point Likert scale developed for a related study (BWS; Sanders-Reio, 2010). These subscales align with the Kellogg model (2008), as discussed above. The BWS is an expansion of White and Bruning’s (2005) Writing Beliefs Inventory, which had two subscales, Transaction and Transmission, previously described. 2.2.4. Writing performance Assessment of student writing in much research and many highstakes tests tends to be based on a single sample, written in 20e 30 min in response to a prompt and graded with a single score (Hillocks, 2008). Although valuable, such assessments have serious shortcomings: their often-inflexible format, lack of authenticity, emphasis on speed over skill, discrimination against students unfamiliar with the topic, and restraints on students’ use of writing strategies (Coker & Lewis, 2008). Writing researchers (e.g., Murphy & Yancy, 2008) and the National Council of Teachers of English (2008) have called for more ecologically valid indicators of writing performance. Here, writing performance, the dependent variable, was assessed via the students’ grades on a 5- to 8-page, structured, take-home assignment, an analysis of a video about three preschools in light of learning theory. Participants completed the surveys during 20e40 min of class time with respect to papers they write at the university. They did so after they understood the writing assignment, but before they could begin working on it, as Bandura recommended (Pajares, 1997). Students received extra credit for participating; no one refused the opportunity. Two professors, each of whom has taught this course, graded all of the papers. The interrater agreement between the graders, .93, was calculated using correlational analysis, as directed by Gay (1992). 2.2. Measures 3. Results 2.2.1. Writing Self-Efficacy Index Writing self-efficacy was assessed with the Writing Self-Efficacy Index (WSI; Sanders-Reio, 2010), which was based on Zimmerman and Bandura’s (1994) Writing Self-Regulatory Efficacy Scale of 25 items primarily relating to the self-regulation of writing projects and processes (e.g., “I can start writing with no difficulty”). Questions addressing substantive and mechanical writing issues were added, based on the research and practice literature, for a total of 60 items. Participants indicated their confidence in their ability to perform a task by making a hash mark on a 10-mm line marked 0 to 100 (e.g., Nietfeld & Schraw, 2002). 3.1. Examination of the measures 3.1.1. Writing Self-Efficacy Index and the modified Writing Apprehension Test PCAs with varimax rotation were used to examine the structures of the WSI and WAT. The WSI had three components according to the Kaiser Criterion and the scree plot: self-efficacy for Substantive, Self-Regulatory, and Mechanical writing skills. The eigenvalues for these components were 16.4, 10.9, and 10.2, respectively; they accounted for 26.9%, 18.5%, and 17.9% of the variance, respectively, J. Sanders-Reio et al. / Learning and Instruction 33 (2014) 1e11 for a total of 63.3% of the variance explained. Most of the items from the Zimmerman and Bandura (1994) scale loaded on the SelfRegulatory subscale. We expected that the three items added to the WAT to assess apprehension about writing mechanics would strengthen the Dislike Writing subscale. However, the Kaiser Criterion and the scree plot indicated that these items formed a separate component, Apprehension About Grammar. One item from the Enjoy Writing scale, “I have no fear of my writing being evaluated,” was dropped because its coefficient was below .30 (12 items remained). Dislike Writing, Enjoy Writing, and Apprehension about Grammar accounted for 23.8%, 23.4%, and 9.1% of the variance, respectively, for a total of 56.3% of the variance explained. The eigenvalues were 6.9, 6.8, and 2.6, respectively. 3.1.2. Beliefs About Writing Survey As the BWS had not been validated, we sought to support the construct validity of this scale via a sequential exploratory factor analysis (EFA)-confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (Worthington & Whittaker, 2006). Using the SPSS 20.0 random data-splitting protocol, we divided the dataset into two subsets of equal size (ns ¼ 369). We then employed an EFA on the first dataset to investigate the factor structure, reduce the number of items as appropriate, and distinguish items that align with a simple structure (Nimon, Zigarmi, Houson, Witt, & Diehl, 2011). Finally, we conducted a CFA with the second subsample, using the remaining items specified by the EFA. 3.1.2.1. EFA (subsample 1). Because of the hypothesized underlying theoretical structure and our expectation that the factors would correlate, we used principal-axis factoring and promax rotation for the EFA (Nimon et al., 2011). According to the scree plot and the Kaiser criterion, the EFA revealed four interpretable factors explaining 43.2% of the variance in the 50 submitted items. The top four writing belief components aligned with Kellogg’s model (2008), supporting their use in this study. Table 1 lists the items in these four subscales. Audience Orientation, which advocates focusing on one’s readers and their interests. (22.3% of the variance; eigenvalue, 6.9) Recursive Process, which reflects an iterative approach to writing (8.1% of the variance; eigenvalue, 2.5) Transaction (White & Bruning, 2005), which reflects affective and cognitive engagement (7.1% of the variance; eigenvalue, 3.7) Transmission (White & Bruning, 2005), which advocates sticking closely to the arguments, information, and quotes provided by authorities (5.7% of the variance; eigenvalue, 1.7) Note that the items forming Transaction and Transmission are not identical to those used by White and Bruning (2005). Two items that White and Bruning included in Transaction loaded on Recursive Process. In addition, each subscale contains a new item: “Writing helps new ideas emerge” in the case of Transaction, and “When writing, it’s best to use proven formats and templates, and then fill in the important information” for Transmission. Finally, several items were dropped from each scale during the exploratory factor analysis (see below). Factor intercorrelations ranged from .10 to .54. Analysis of the pattern and structure coefficients that cross-loaded or were below .40 suggested that 12 of the items could be deleted without affecting content coverage (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1998). Audience Orientation had 14 items; Recursive Process, 5 items; Transaction, 7 items; and Transmission, 5 items, in the final subscales. 5 Table 1 Beliefs About Writing Survey: subscales and items. Transmission: 5 items, a ¼ .65 Good writers include a lot of quotes from authorities in their writing. Writing should focus on the information in books and articles. The key to successful writing is accurately reporting what authorities think. The most important reason to write is to report what authorities think about a subject. When writing, it’s best to use proven formats and templates, and then fill in the important information. Transaction: 7 items, a ¼ .78 Writing is a process involving a lot of emotion. Writing helps me understand better what I’m thinking about. Writing helps me see the complexity of ideas. My thoughts and ideas become more clear to me as I write and rewrite. Writing is often an emotional experience. Writers need to immerse themselves in their writing. Writing helps new ideas emerge. Recursive Process: 5 items, a ¼ .72 Writing requires going back over it to improve what has been written. Good writing involves editing many times. Writing is a process of reviewing, revisioning, and rethinking. Revision is a multi-stage process. The key to good writing is revising. Audience Orientation: 14 items, a ¼ .85 Good writers make complicated information clear. Good writers are sensitive to their readers. Good writers support their points effectively. Good writers adapt their message to their readers. The key to good writing is conveying information clearly. Good writers keep their audience in mind. Good writers thoroughly explain their opinions and findings. Good writers are oriented toward their readers. Good writers are logical and convincing. Good writers are reader-friendly. Good writing sounds natural, not stiff. Good writers don’t let their choice of words overshadow their message. It’s important to select the words that suit your purpose, audience, and occasion. Good writers anticipate and answer their audience’s questions. 3.1.2.2. CFA (subsample 2). We arranged the 31 items identified by the EFA in four empirically identified factors to conduct the CFA with intercorrelated factors on the second subsample. Overall, the goodness-of-fit indices revealed that the CFA model had an acceptable fit to the data. The c2 analysis results (c2 [428] ¼ 986.64, p < .001) suggested that the data did not fit the model adequately; yet, c2 tests have been shown to be especially sensitive to larger sample sizes, for which statistical significance is often the result (Kline, 1998). However, other methods demonstrated evidence of factorial validity. The c2/df ratio yielded a value of 2.31, considered acceptable fit (less than 3.0 is best; Kline, 1998). The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA ¼ .059; CI 90 ¼ .054, .061) was less than .06, also suggesting acceptable fit (less than .06 is recommended; Hu & Bentler, 1999). The comparative fit index (CFI ¼ .91) and Adjusted Good-of-Fit-Index (AGFI ¼ .90) both indicated acceptable fit (Kline, 1998) as well, although a criterion value closer to .95 is desirable (Worthington & Whittaker, 2006). 3.1.2.3. Reliability (overall sample). The Cronbach’s alphas of the Beliefs About Writing Survey subscales ranged from .65 to .85 (see Table 2). All but one of these subscales (Transmission) exceeded the .7 minimum that researchers prefer (e.g., Hair et al., 1998; Nunnally, 1967). The Cronbach’s alphas of the Writing Self-Efficacy Index subscales ranged from .94 to .98, and those of the modified WAT ranged from .87 to .92. Table 2 lists the means and standard deviations of each subscale. 6 J. Sanders-Reio et al. / Learning and Instruction 33 (2014) 1e11 Table 2 Reliabilities and sample items for the subscales of the Beliefs About Writing Survey, the Writing Self-Efficacy Index, and the modified Writing Apprehension Test. Subscale Cronbach’s a Sample item 5 .65 The most important reason to write is to report what authorities think about a subject. No. items Beliefs About Writing Survey Knowledge Telling Transmission Knowledge Transforming Transaction Recursive Process Knowledge Crafting Audience Orientation 7 5 .78 .72 Writing helps me understand what I’m thinking about. Writing is a process of reviewing, revisioning, and rethinking. 14 .85 Good writers anticipate and answer their audience’s questions. Writing Self-Efficacy Index Substantive Self-Regulatory Mechanical 25 19 11 .98 .94 .95 I can logically make the points I want to convey. I can start writing with no difficulty. I can correctly punctuate the papers I write. Modified Writing Apprehension Test Enjoy Writing Dislike Writing Apprehension About Grammar 12 13 3 .92 .92 .87 I like seeing my thoughts on paper. I expect to do poorly in composition classes even before I enter them. I’m afraid that I may make a punctuation error. 3.1.3. Grading All participants submitted their papers to Turnitin.com to check for plagiarism. Two professors, one the actual instructor and another who has taught this course, assigned each paper a letter grade ranging from A to F, including pluses and minuses. Note that the College of Education required the students to earn at least a C on this paper to pass the course. Those who fell short could rewrite. Papers were evaluated with a rubric assessing course content, substantive writing skills (i.e., development, clarity, and organization), and mechanical writing skills (i.e., usage and grammar). Students had to demonstrate basic competence in all three of these areas to pass. For this study, grades were coded on a scale of 1e12 (from 1 for an F and 2 for a D- to 12 for an A). The mean grade of the two professors was 8.1 (B-), with 30.2% receiving an A or A-, and 28.9% earning less than the C required. The actual course grades were almost identical (mean grade of 8.2 [B-]). As part of the battery of measures, students predicted the grade that they would receive for this assignment. The correlation between the grade students predicted and the grade they received was .13 (p < .001) (Table 3). Table 3 Means and standard deviations of the independent and dependent variables. Subscale Beliefs About Writing Survey Knowledge Telling Transmission Knowledge Transforming Transaction Recursive Process Knowledge Crafting Audience Orientation Item M Subscale M SD 2.4 11.8 3.1 4.0 4.1 27.8 20.7 3.8 2.8 4.1 57.0 6.8 73.6 59.8 67.9 1840.1 1136.4 747.4 407.3 309.7 213.1 Modified Writing Apprehension Test Enjoy Writing Dislike Writing Apprehension About Grammar 3.4 2.3 2.8 41.0 29.8 8.4 9.6 9.9 3.5 Writing Performance Grade 8.1a Writing Self-Efficacy Index Substantive Self-Regulatory Mechanical 3.0 (A ¼ 12, A ¼ 11. F ¼ 1. 8.3 is equivalent to a B.). a The writing grade is a letter grade from A to F (with pluses and minuses). 3.2. Examination of the correlations between the variables Table 4 lists the correlations between the variables, which indicate that students who received higher grades for their papers had higher writing self-efficacy and lower writing apprehension, as they did in previous studies (e.g., Pajares & Valiante, 1997). Correlations between writing self-efficacy and writing performance were within the range reported in previous research, but somewhat lower than the norm (e.g., Pajares & Valiante, 1999). Notably, the new writing apprehension subscale, Apprehension About Grammar, had a stronger negative correlation with writing performance than did Dislike Writing, the traditional measure of writing apprehension (Daly & Miller, 1975). Only the two new beliefs about writing, Audience Orientation and Recursive Process, positively correlated with both writing performance and the three writing self-efficacy subscales, and also negatively related to both measures of writing apprehension. Audience Orientation had the strongest positive relations with writing performance and self-efficacy. Transaction, the belief in engaging with the writing process, was the strongest positive correlate of all three writing self-efficacy subscales as well as Enjoy Writing. However, it did not relate to writing performance. Transmission, which advocates basing one’s papers on the arguments and information published by authorities, negatively related to both writing performance and self-efficacy, and positively related to writing apprehension. Transmission was the only belief about writing that positively correlated with Apprehension About Grammar. All three writing self-efficacy subscales positively related to writing performance and negatively related to writing apprehension, including Apprehension About Grammar. Both Dislike Writing and Apprehension About Grammar negatively related to writing performance. These results differ from White and Bruning’s (2005), where Transaction related positively to writing performance and self-efficacy, but not to apprehension, and where Transmission negatively related to writing performance but did not relate to self-efficacy or apprehension. 3.3. Relations among the research variables To test the relations among the research variables Hypothesis 1, we first ran a series of simultaneous regressions (see Table 5). In each case, the hypothesis (Hypotheses 1a-i) was at least partially supported. The effect sizes (R2) associated with most of the regression results ranged from moderate (.06e.24) to large (.25; J. Sanders-Reio et al. / Learning and Instruction 33 (2014) 1e11 7 Table 4 Correlations among beliefs about writing, writing self-efficacy, writing apprehension, and writing performance. Grade Grade Transmission Transaction Recursive Audience SE Substantive SE Self-Regulatory SE Mechanical Enjoy Writing Dislike Writing Apprehension About Grammar 1 .20*** .01 .12** .18*** .18*** .15*** .23*** .11** .17*** .26*** Beliefs About Writing Knowledge Telling Knowledge Transforming Transmission Transaction 1 .03* .26*** .03 .15*** 12** .13** .11** .20*** .15*** Self-efficacy Apprehension Knowledge Crafting Recursive Audience Substantive Self-Regulatory Mechanical Enjoy Writing Dislike Writing 1 .76*** .20*** 1 Apprehension About Grammar 1 .12** .40** .32*** .30*** .24*** .45*** .32*** .00 1 .09** .11** .04 .04 .07* .10** .00 1 .30*** .24*** .25*** .24*** .19*** .01 1 .83*** .72*** .57*** .58*** .22*** 1 .63*** .60*** .59*** .20*** 1 .42*** .48*** .43*** .40*** 1 Note. N ¼ 738. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. Cohen, 1988). (When referring to the scales as they relate to the regressions, we are referring to the scales’ scores.) We first tested our hypothesis that Audience Orientation, Recursive Process, and Transaction would positively predict all three writing self-efficacy subscales, while Transmission would be a negative predictor (Hypotheses 1a, d). The equations indicated that the beliefs about writing predicted self-efficacy for the following: Substantive writing skills: R ¼ .40, F(4, 733) ¼ 34.83, R2 ¼ .16, p < .001. Writing Self-Regulation: R ¼ .35, F(4, 733) ¼ 24.94, R2 ¼ .12, p < .001. Writing Mechanics: R ¼ .32, F(4, 733) ¼ 21.17, R2 ¼ .10, p < .001. In each of these regressions, Audience Orientation and Transaction were significant positive predictors, while Transmission was a significant negative predictor, as hypothesized. However, Recursive Process was not a significant predictor in any of these equations. We ran additional simultaneous regressions to test our hypothesis that Audience Orientation, Recursive Process, and Transaction would positively predict Enjoy Writing and negatively predict Dislike Writing and Apprehension About Grammar (Hypothesis 1c), while Transmission would positively predict Dislike Writing and Apprehension About Grammar and negatively predict Enjoy Writing (Hypothesis 1f). The beliefs about writing predicted the following: Enjoy Writing: R ¼ .46, F(4, 733) ¼ 49.47, R2 ¼ .21, p < .001. Dislike Writing: R ¼ .38, F(4, 733) ¼ 30.41, R2 ¼ .14, p < .001. Apprehension About Grammar: R ¼ .16, F(4, 733) ¼ 4.49, R2 ¼ .02, p ¼ .001. As expected, Audience Orientation and Transaction positively predicted Enjoy Writing, while Transmission was a negative predictor. Additionally, as hypothesized, Audience Orientation and Transaction were negative predictors of Dislike Writing, while Transmission was a positive predictor. Transmission was the only significant predictor of Apprehension About Grammar. Recursive Process did not attain statistical significance in any of these regression analyses. In the regression equation testing whether Audience Orientation, Recursive Process, and Transaction positively predict writing performance (Hypothesis 1b), and Transmission negatively predicts writing performance (Hypothesis 1e), beliefs about writing did predict the students’ writing grades (R ¼ .29, F(4, 733) ¼ 16.83, R2 ¼ .08, p < .001). Audience Orientation was a positive predictor, and Transaction and Transmission were negative predictors. Again, Recursive Process was not a significant predictor. A simultaneous regression confirmed Hypothesis 1g, which predicted that all three writing self-efficacy subscales would positively predict writing performance (R ¼ .24, F(3, 734) ¼ 14.31, R2 ¼ .06, p < .001). As expected, Self-Efficacy for Mechanical writing skills positively predicted the writing grades, but, contrary to our hypotheses, the remaining writing self-efficacy scales did not. Hypothesis 1h predicted that the writing self-efficacy subscales would each negatively predict Dislike Writing and Apprehension About Grammar, and positively predict Enjoy Writing. Writing SelfEfficacy predicted the following: Enjoy Writing: R ¼ .61, F(3, 734) ¼ 145.37, R2 ¼ .37, p < .001. Dislike Writing: R ¼ .61, F(3, 734) ¼ 148.36, R2 ¼ .38, p < .001. Apprehension About Grammar: R ¼ .45, F(3, 734) ¼ 63.35, R2 ¼ .21, p < .001. Self-Efficacy for Substantive writing skills and Writing SelfRegulation positively predicted Enjoy Writing and negatively predicted Dislike Writing, as hypothesized, but did not predict Apprehension About Grammar. As expected, Self-Efficacy for Mechanical writing skills was a negative predictor of Dislike Writing, a powerful predictor of Apprehension About Grammar, and a predictor of Enjoy Writing. Hypothesis 1i predicted that Dislike Writing and Apprehension About Grammar would negatively predict the students’ writing grades while Enjoy Writing would be a positive predictor. The three subscales related to writing apprehension did predict writing performance (R ¼ .27, F(3, 734) ¼ 18.66, R2 ¼ .07, p < .001). Apprehension About Grammar negatively predicted writing performance, as expected, while Enjoy Writing and Dislike Writing did not contribute significantly to the regression equation. 3.4. Predicting writing performance In accord with hierarchical regression protocol (Hair et al., 1998), we used the research literature to guide the order of entry of the independent variables in the hierarchical regression analysis (beliefs about writing, writing self-efficacy, and writing apprehension) for predicting the criterion variable, writing performance (see Table 6). As discussed above, the order in which we 8 J. Sanders-Reio et al. / Learning and Instruction 33 (2014) 1e11 Table 5 Summary of simultaneous regression analyses predicting writing self-efficacy, writing apprehension, and writing performance. Variable B Beliefs About Writing Predicting Writing Self-Efficacy (Substantive) Audience 12.51 Recursive 3.59 Transaction 24.47 Transmission .18.54 Writing Self-Efficacy (Self-Regulatory) Audience 7.08 Recursive 3.17 Transaction 18.81 Transmission .12.40 Writing Self-Efficacy (Mechanical) Audience 5.83 Recursive 2.32 Transaction 9.43 Transmission .9.38 Writing Apprehension (Enjoy) Audience .11 Recursive .02 Transaction 1.03 Transmission .31 Writing Apprehension (Dislike) Audience .12 Recursive .02 Transaction .72 Transmission .62 Writing Apprehension (Grammar) Audience .01 Recursive .05 Transaction .01 Transmission .18 Writing Performance Audience .09 Recursive .06 Transaction .07 Transmission .19 SE B b Table 6 Summary hierarchical regression analysis predicting writing performance from beliefs about writing, writing self-efficacy, and writing apprehension. Writing Grade Variable 2.23 5.05 3.96 4.60 .21*** .03 .23*** .14*** 1.73 3.93 3.08 3.58 .16*** .03 .23*** .12** 1.24 2.73 2.12 2.49 .19*** .03 .17*** .14*** .05 .12 .09 .11 .08* .01 .41*** .11** .06 .12 .10 .11 .08* .01 .28*** .20*** .02 .05 .04 .04 .02 .04 .01 .16*** .02 .04 .03 .04 .22*** .06 .09*** .20*** .00 .00 .00 .23*** .41*** .01 .00 .00 .00 .23*** .34*** .10* Writing Self-Efficacy Predicting Writing Apprehension (Enjoy) Substantive .01 Self-Regulatory .01 Mechanical .00 Writing Apprehension (Dislike) Substantive .01 Self-Regulatory .01 Mechanical .01 Writing Apprehension (Grammar) Substantive .00 Self-Regulatory .00 Mechanical .01 Predicting Writing Performance Substantive .00 Self-Regulatory .00 Mechanical .01 .00 .00 .00 .18** .01 .57*** .00 .00 .01 .07 .05 .23*** Writing Apprehension Predicting Writing Performance Enjoy .01 Dislike .02 Grammar .19 .02 .02 .03 .02 .07 .23*** Note. N ¼ 738. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. entered the variables was guided first by researchers (e.g., White & Bruning, 2005) who suggested that students’ beliefs about writing influence their writing process, which includes their selection of writing strategies. Using sound writing strategies in turn creates mastery experiences that, according to Bandura (1997), enhance self-efficacy. Thus, we entered the beliefs about writing in the first block before the writing self-efficacy beliefs in the second block. With respect to apprehension, the Pajares group’s path-analytic research (e.g., Pajares & Johnson, 1994) Step 1: Beliefs About Writing Knowledge Telling Transmission Knowledge Transforming Transaction Recursive Process Knowledge Crafting Audience Orientation Block Step 2: Writing Self-Efficacy Substantive Self-Regulatory Mechanical Block Step 3: Writing Apprehension Enjoy Writing Dislike Writing Apprehension About Grammar Block Total R2 b DR2 .15*** .11*** .07* .19*** .08*** .04 .02 .09* .03*** .02 .01 .19*** .03*** .15*** Note. N ¼ 738. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. indicated that writing self-efficacy can nullify writing apprehension. Therefore, we entered the writing apprehension scores in the third block after the writing self-efficacy beliefs. Together, the three blocks of variables explained 15.0% of the variance in writing performance [R ¼ .39, F(10, 737) ¼ 12.30, p < .001]. As a group, the beliefs about writing in the first block explained 8.4% of the variance in writing grades (R ¼ .29, F(4, 733) ¼ 16.83, p < .001). Each of the four beliefs independently and significantly predicted writing performance. Audience Orientation, the most powerful predictor, and Recursive Process positively predicted performance, while Transmission and Transaction were negative predictors (Hypotheses 2a, b). The three writing self-efficacy scales, entered in the second block, explained an additional 3.3% of the variance (R ¼ .34, FD (3, 730) ¼ 9.23, p < .001, Hypothesis 2c); Self-Efficacy for Mechanical writing skills was the only significant predictor (positive). Finally, the three writing apprehension variables entered in the third block increased the variance explained by a final 3.3% (R ¼ .39, FD (3, 727) ¼ 7.69, p < .001, Hypothesis 2d). As in previous studies (e.g., Pajares & Valiante, 1997), the original WAT (the Dislike Writing and Enjoy Writing subscales here) did not independently predict performance. However, Apprehension About Grammar, the new subscale, negatively predicted incremental variance in performance above and beyond the effects of both beliefs about writing and writing self-efficacy (b ¼ .19, p < .001). Inasmuch as beliefs about writing independently explained variance in writing performance, Hypotheses 2a and 2b were supported. Likewise, because both writing self-efficacy and apprehension uniquely predicted writing performance beyond beliefs about writing, Hypotheses 2c and 2d were supported as well. Overall, beliefs about writing explained the most variance in writing performance, with Audience Orientation being the most powerful predictor. 3.4.1. Predictive validity To demonstrate further that beliefs about writing, a form of domain-related beliefs, can predict writing performance beyond the more researched writing self-efficacy and writing apprehension J. Sanders-Reio et al. / Learning and Instruction 33 (2014) 1e11 variables included in this study (Hypothesis 2e), we conducted another hierarchical regression analysis. In this case we entered the two more extensively studied sets of variables before the beliefs about writing, and entered self-efficacy first, followed by writing apprehension, and then beliefs about writing. The findings provided evidence of the predictive validity of the model presented here as beliefs about writing explained an additional 5.8% of the variance in writing performance after controlling for writing selfefficacy (5.5%) and writing apprehension (3.2%). Notably, beliefs about writing explained the most variance in the regression equation even when entered in the third and final step of the equation. Finally, we ran the entire regression model (primary) using only the original items of Zimmerman and Bandura’s Writing Self-Regulatory Efficacy Scale (1994); this measure explained less variance (1.3%) than the more comprehensive Writing Self-Efficacy Index (3.3%). 4. Discussion This study investigated whether beliefs about writing, including two new beliefs, Audience Orientation and Recursive Process, relate to writing performance and two of its established correlates, writing self-efficacy and apprehension. We hypothesized that the beliefs about writing would predict variance in writing grades over and above the effects of writing self-efficacy and writing apprehension. We further hypothesized that a new subscale assessing apprehension about making grammatical and other mechanical writing errors would strengthen the traditional measure of writing apprehension (Daly & Miller, 1975), which assesses anxiety about showing others one’s written work and having it critiqued. 4.1. Beliefs about writing The participants’ beliefs about writing did relate to their writing self-efficacy (Hypotheses 1a, 1d), apprehension (Hypotheses 1c, 1f), and performance (Hypotheses 1b, 1e), and they did predict unique variance in the students’ grades for their written work (Hypothesis 2a, 2b). We have used these results to develop the following profiles of the four beliefs about writing we examined. Audience Orientation, the most adaptive belief about writing studied here, is associated with expert writing practice (Kellogg, 2008). This belief reflects a concern for the needs and interests of one’s readers. Items addressing classic characteristics of good writing, such as development and clarity, loaded on this belief. This makes sense because clarity and development imply an audience for whom the text is clear, understandable, and for whom concepts and information are explained with appropriate detail. The adaptiveness of this belief confirms Ong’s (1975) view that being able to interpret one’s text from a reader’s point of view “is one of the things that separates the beginning graduate student or even the brilliant undergraduate from the mature scholar” (p. 19). Recursive Process, a belief related to stage two of Kellogg’s (2008) model, sees each aspect of the writing process as a time to rethink, revise, and revision. We suspect that this belief would be even more adaptive in the context of longer assignments and writing that is held to particularly high standards, such as dissertations and articles written for publication. Transaction, which maintains that writing involves cognitive and emotional engagement, positively predicted writing performance in White and Bruning’s (2005) study, but it was a negative predictor here. However, Transaction was a strong positive correlate of Enjoy Writing and a strong and negative correlate of both types of writing apprehension. The enjoyment of writing that Transaction seems to engender may keep writers working productively during writing instruction and while crafting papers that 9 entail many iterations. Thus, we expect that this belief, too, may be more adaptive in the context of more complex assignments written for higher standards. Transmission, which endorses the practice of relying on authorities and their published arguments and quotes, was maladaptive as those who embraced it received lower grades on their papers and were less self-efficacious and more apprehensive about writing, particularly with respect to grammar and writing mechanics. This belief could easily foster a mechanical and/or safe, selfprotective, and detached approach to writing that entails stringing other writers’ quotes together, plugging new text into established formats, or simply using new words to convey established lines of argument laid out by authorities in encyclopedias and textbooks. We acknowledge that the correlations between the beliefs about writing and writing performance are modest. However, we contend that these relations are meaningful. Even strong adherence to a belief about writing does not imply the skill or the will to act on that belief. As Kellogg (2008) states, appreciating that one has an audience does not mean that one is able to see one’s own text from the perspective of that audience or that one has the skills, motivation, or executive control to adapt one’s message to that audience. 4.2. Writing self-efficacy and writing apprehension As expected, participants with high writing self-efficacy had low writing apprehension and enjoyed writing more, and those who had low writing self-efficacy enjoyed writing less and were more apprehensive about writing (Hypothesis 1h). Participants who were more apprehensive received lower grades on their papers, while those with high writing self-efficacy received higher grades on their papers, but the magnitude of the association was modest (Hypothesis 2c). In several of the Pajares group’s studies, writing self-efficacy nullified the influence of writing apprehension (e.g., Pajares & Valiante, 1997). That occurred here as well, but only with respect to the traditional measure of apprehension that Pajares used. Apprehension About Grammar, a new subscale unavailable to Pajares, accounted for significant, unique, negative variance in the regression equation. The disparity between the magnitude of these self-efficacy results and those in the literature may stem from the differences between the studies. For example, the participants in this study were undergraduates enrolled in an upper-level course, while most previous research involved younger students. This study also used the grade students received on a take-home assignment to measure writing performance. Grading standards may have been more demanding than they would be for short assignments written on demand in 15e20 min. In addition, the wide disparity between the grade the participants predicted they would earn and the grade they actually received (r ¼ .13) indicates that their self-efficacy judgments may not have been well calibrated. Many reported that they had commonly received high grades (usually A’s) on written assignments at other schools, but their writing performance here was not in line with these reports. 4.3. Limitations Although we investigated a number of beliefs about writing, others are possible. Beliefs about writing are culturally constructed and disseminated, and may relate to the pedagogy of teaching writing (Silva & Nicholls, 1993), previous writing experiences (White & Bruning, 2005), genre, and context. Thus, students’ beliefs about writing may change as they work with new genres or media, or as teachers develop new methods of writing instruction. In addition, the instruments developed for this study may need 10 J. Sanders-Reio et al. / Learning and Instruction 33 (2014) 1e11 further refinement (e.g., replication with more diverse populations in terms of academic discipline and writing expertise). Further, the study used a correlational design, which does not allow the exploration of causal relations. The participants were primarily Hispanic females, limiting the generalizability of the results to other groups. Finally, writing performance, the dependent variable, was operationalized as the grade participants received on only one paper, which does not reflect the variance in students’ writing performance (Hayes, Hatch, & Silk, 2000). 4.4. Future directions Further work with these variables is needed with other writing assignments and contexts, and with participants who are more varied and balanced with respect to gender, race, ethnicity, and writing expertise. Research is needed to identify the mechanisms by which beliefs about writing may affect writing performance. It may be the case, as this study indicates, that there is an affective link, as certain beliefs about writing seem to foster writing apprehension or, by contrast, increase the extent to which students like to write. It is also possible, as many of the researchers cited here theorized, that there is also a cognitive link mediated by the writer’s choice of strategies or a student’s openness to instruction in specific strategies. For example, students might not attend to instruction in revision if they believe that good writers do not revise but write it right on their first attempt. If beliefs about writing do relate to openness to instruction, it will be valuable to determine whether these beliefs are amenable to change and whether certain changes in a student’s beliefs foreshadow improvements in attitudes about writing and writing performance itself. These results also support the possibility that beliefs about writing could be a worthwhile new leverage point for teaching students to write. It may be useful to modify writing instruction to emphasize the mindsets and approaches associated with adaptive beliefs and minimize those related to maladaptive and ineffective beliefs. For example, assignments can be structured to encourage students to have a stronger sense of audience. Additionally, teachers can assign fewer papers and more revision so that onedraft writing becomes the exception and revision cycles the norm. Strategies, such as taking notes from outside texts, selecting and incorporating quotations, and varying and increasing the sophistication of one’s vocabulary, can be presented so that they remain flexible and do not deteriorate into mechanical cutting and pasting. Finally, the strong negative relation of Apprehension About Grammar to writing performance indicates that we may need to be less indignant about mechanical errors and develop approaches to teaching grammar and correctness that are less likely to produce counterproductive levels of anxiety. 4.5. Conclusions These results support Bandura’s (1997) views about the importance of beliefs in that a relatively new type of belief, beliefs about a domain, accounted for significant, unique variance in performance. The fact that these beliefs predict performance in conjunction with self-efficacy beliefs supports the possibility that constellations of beliefs (e.g., domain-specific beliefs coupled with epistemic beliefs [Mateos et al., 2010] or self-efficacy beliefs) may affect performance in tandem. Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge Lucia Mason, as well as the three anonymous reviewers who so thoroughly and productively reviewed this manuscript. References Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44, 1175e1184. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175. Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman. Beach, R., & Friedrich, T. (2006). Response to writing. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (pp. 222e234). New York: Guilford. Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (1987). The psychology of written composition. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Bline, D., Lowe, D. R., Meixner, W. F., Nouri, H., & Pearce, K. (2001). A research note on the dimensionality of Daly and Miller’s Writing Apprehension Scale. Written Communication, 18(1), 61e79. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0741088301018001003. Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Coker, D., & Lewis, W. E. (2008). Beyond writing next: a discussion of writing research and instructional uncertainty. Harvard Educational Review, 78(1), 231e251. Daly, J. A., & Miller, M. D. (1975). The empirical development of an instrument to measure writing apprehension. Research in the Teaching of English, 9, 242e 249. Gay, L. R. (1992). Educational research: Competencies for analysis and application (4th ed.). New York: Merrill. Graham, S., Schwartz, S. S., & MacArthur, C. A. (1993). Knowledge of writing and the composing process, attitude toward writing, and self-efficacy for students with and without learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 26, 237e249. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/002221949302600404. Hair, J. F., Jr., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Hayes, J. R., & Flower, L. S. (1980). Identifying the organization of writing processes. In L. W. Gregg, & E. R. Steinbert (Eds.), Cognitive processes in writing (pp. 3e30). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Hayes, J. R., Hatch, J., & Silk, C. M. (2000). Does holistic assessment predict writing performance? Estimating the consistency of student performance on holistically scored writing assessments. Written Communication, 17(1), 3e26. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1177/0741088300017001001. Hillocks, G., Jr. (2008). Writing in secondary schools. In C. Bazerman (Ed.), Handbook of research on writing (pp. 311e329). New York: Erlbaum. Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes to covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1e55. Kellogg, R. T. (2008). Training writing skills: a cognitive developmental perspective. Journal of Writing Research, 1(1), 1e26. Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press. Lavelle, E. (1993). Development and validation of an inventory to assess processes in college composition. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 63, 489e499. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1993.tb01073.x. Mateos, M., Cuevas, I., Martin, E., Martin, A., Echeita, G., & Luna, M. (2010). Reading to write and argumentation: the role of epistemological, reading and writing beliefs. Journal of Research in Reading, 34, 281e297. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ j.1467-9817.2010.01437.x. McCarthy, P., Meier, S., & Rinderer, R. (1985). Self-efficacy and writing: a different view of self-evaluation. College Composition and Communication, 36, 465e471. Meier, S., McCarthy, P. R., & Schmeck, R. R. (1984). Validity of self-efficacy as a predictor of writing performance. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 8(2), 107e 120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01173038. Miller, C. R., & Charney, D. (2008). Persuasion, audience, and argument. In C. Bazerman (Ed.), Handbook of research on writing (pp. 583e598). New York: Erlbaum. Murphy, S., & Yancy, K. B. (2008). Construct and consequence: validity in writing assessment. In C. Bazerman (Ed.), Handbook of research on writing (pp. 365e 385). New York: Erlbaum. Murray, D. M. (1991). The craft of revision. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. National Council of Teachers of English, James R. Squire Office of Policy Research. (2008). Writing now: A policy research brief produced by the National Council of Teachers of English. Retrieved January 15, 2009, from http://www.ncte.org/ library/NCTEFiles/Resources/PolicyResearch/WrtgResearchBrief.pdf. Nietfeld, J. L., & Schraw, G. (2002). The effect of knowledge and strategy training on monitoring accuracy. The Journal of Educational Research, 95(3), 131e142. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1080/00220670209596583. Nimon, K., Zigarmi, D., Houson, D., Witt, D., & Diehl, J. (2011). The work cognition inventory: initial evidence of construct validity. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 22, 7e33. Nunnally, J. C. (1967). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw Hill. Ong, W. J. (1975). The writer’s audience is always a fiction. PMLA, 91, 9e21. Pajares, F. (1997). Current directions in self-efficacy research. In M. Maehr, & P. R. Pintrich (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement (pp. 1e49). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Pajares, F., & Johnson, M. J. (1994). Confidence and competence in writing: the role of self-efficacy, outcome expectancy, and apprehension. Research in the Teaching of English, 28(3), 313e331. J. Sanders-Reio et al. / Learning and Instruction 33 (2014) 1e11 Pajares, F., & Valiante, G. (1997). Influence of self-efficacy on elementary students’ writing. The Journal of Educational Research, 90(6), 353e360. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/00220671.1997.10544593. Pajares, F., & Valiante, G. (1999). Grade level and gender differences in the writing self-beliefs of middle school students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 24, 390e405. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1998.0995. Palmquist, M., & Young, R. (1992). The notion of giftedness and student expectations about writing. Written Communication, 9, 137e168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/ 0741088392009001004. Sanders-Reio, J. (2010). Investigation of the relations between domain-specific beliefs about writing, writing self-efficacy, writing apprehension, and writing performance in undergraduates. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. College Park: University of Maryland. Scheuer, N., de la Cruz, M., Pozo, J. I., Huarte, M. F., & Sola, G. (2006). The mind is not a black box: children’s ideas about the writing process. Learning and Instruction, 16, 72e85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.12.007. Schommer-Aikins, M. (2004). Explaining the epistemological belief system: introducing the embedded systemic model and coordinated research approach. Educational Psychologist, 39, 19e29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/ s15326985ep3901_3. Schraw, G., & Bruning, R. (1996). Readers’ implicit models of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 31, 290e305. http://dx.doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.31.3.4. 11 Schraw, G., & Bruning, R. (1999). How implicit models of reading affect motivation to read and reading engagement. Scientific Studies of Reading, 3(3), 281e302. Schunk, D. H., & Swartz, C. W. (1993). Goals and progress feedback: effects on selfefficacy and writing achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 18, 337e354. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1993.1024. Silva, T., & Nicholls, J. G. (1993). College students as writing theorists: goals and beliefs about the causes of success. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 18, 281e293. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1993.1021. Smith, M. W., Cheville, J., & Hillocks, G., Jr. (2006). “I guess I’d better watch my English”: grammars and the teaching of the English language arts. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (pp. 263e274). New York: Guilford. White, M. J., & Bruning, R. (2005). Implicit writing beliefs and their relation to writing quality. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 30, 166e189. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2004.07.002. Worthington, R. I., & Whittaker, T. A. (2006). Scale development research: a content analysis and recommendations for best practices. The Counseling Psychologist, 34, 806e838. Zimmerman, B. J., & Bandura, A. (1994). Impact of self-regulatory influences on writing course attainment. American Educational Research Journal, 31, 845e862. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00028312031004845. Zinsser, W. (1976). On writing well. New York: HarperCollins.