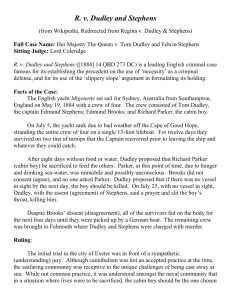

The case of R v Dudley and Stephens (1884) is a leading English criminal case which established a precedent throughout the common law world that necessity is not a defence to a charge of murder. The case concerned survival cannibalism following a shipwreck, and its purported justification on the basis of a custom of the sea. The four-man crew of the wrecked yacht Mignonette were cast adrift in a small lifeboat without provisions. After nearly three weeks at sea, and with little hope of rescue, two of the crew, Tom Dudley and Edwin Stephens, decided that in order to save their own lives they would need to kill and eat the ship's 17-year-old cabin boy Richard Parker, who by that time had fallen seriously ill after drinking seawater. This they did. The defendants were found guilty and were sentenced to the statutory death penalty, though with a recommendation of mercy. The Queen commuted their sentences to six months' imprisonment, and they were released after four months. The case was controversial at the time, and it remains so today. Some people believe that Dudley and Stephens were justified in killing Parker in order to save their own lives, while others believe that they committed murder. The court's decision in this case was based on the principle that the law must be applied fairly and equally to everyone, regardless of the circumstances. If necessity were admitted as a defence to murder, it would create a dangerous precedent that could be used to justify other heinous crimes. The case also raises important ethical questions about the value of human life and the limits of self-defence. Is it ever right to kill one person in order to save another? If so, under what circumstances? These are questions that have been debated by philosophers and legal scholars for centuries, and there are no easy answers. The case of R v Dudley and Stephens is a reminder that even in the most extreme circumstances, we must uphold the rule of law and the fundamental principles of human rights.