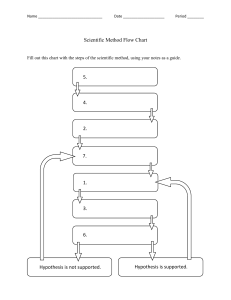

1.5: Scientific Investigations What Turned the Water Orange? If you were walking in the woods and saw this stream, you probably would wonder what made the water turn orange. Is the water orange because of something growing in it? Is it polluted with some kind of chemicals? To answer these questions, you might do a little research. For example, you might ask local people if they know why the water is orange, or you might try to learn more about it online. If you still haven't found answers, you could undertake a scientific investigation . In short, you could "do" science . Figure 1.5.11.5.1:Rio Tinto river "Doing" Science Science is more about doing than knowing. Scientists are always trying to learn more and gain a better understanding of the natural world. There are basic methods of gaining knowledge that is common to all of science . At the heart of science is the scientific investigation .A scientific investigation is a plan for asking questions and testing possible answers in order to advance scientific knowledge. Figure 1.5.21.5.2 outlines the steps of the scientific method . Science textbooks often present this simple, linear "recipe" for a scientific investigation . This is an oversimplification of how science is actually done, but it does highlight the basic plan and purpose of any scientific investigation : testing ideas with evidence . We will use this flowchart to help explain the overall format for scientific inquiry. Science is actually a complex endeavor that cannot be reduced to a single, linear sequence of steps, like the instructions on a package of cake mix. Real science is nonlinear, iterative (repetitive), creative, unpredictable, and exciting. Scientists often undertake the steps of an investigation in a different sequence, or they repeat the same steps many times as they gain more information and develop new ideas. Scientific investigations often raise new questions as old ones are answered. Successive investigations may address the same questions but at ever-deeper levels. Alternatively, an investigation might lead to an unexpected observation that sparks a new question and takes the research in a completely different direction. Knowing how scientists "do" science can help you in your everyday life, even if you aren't a scientist. Some steps of the scientific process — such as asking questions and evaluating evidence — can be applied to answering real-life questions and solving practical problems. Figure 1.5.21.5.2: The Scientific Method : The scientific method is a process for gathering data and processing information. It provides well-defined steps to standardize how scientific knowledge is gathered through a logical, rational problem-solving method. This diagram shows the steps of the scientific method , which are listed below. Making Observations A scientific investigation typically begins with observations. An observation is anything that is detected through human senses or with instruments and measuring devices that enhance human senses. We usually think of observations as things we see with our eyes, but we can also make observations with our sense of touch , smell, taste, or hearing . In addition, we can extend and improve our own senses with instruments such as thermometers and microscopes. Other instruments can be used to sense things that human senses cannot detect at all, such as ultraviolet light or radio waves. Sometimes chance observations lead to important scientific discoveries. One such observation was made by the Scottish biologist Alexander Fleming (Figure 1.5.31.5.3) in the 1920s. Fleming's name may sound familiar to you because he is famous for the discovery in question. Fleming had been growing a certain type of bacteria on glass plates in his lab when he noticed that one of the plates had been contaminated with mold. On closer examination, Fleming observed that the area around the mold was free of bacteria . Figure 1.5.31.5.3: Alexander Fleming experimenting with penicillin and bacteria in his lab in the 1940s. Asking Questions Observations often lead to interesting questions. This is especially true if the observer is thinking like a scientist. Having scientific training and knowledge is also useful. Relevant background knowledge and logical thinking help make sense of observations so the observer can form particularly salient questions. Fleming, for example, wondered whether the mold — or some substance it produced — had killed bacteria on the plate. Fortunately for us, Fleming didn't just throw out the mold-contaminated plate. Instead, he investigated his question and in so doing, discovered the antibiotic penicillin. Hypothesis Formation To find the answer to a question, the next step in a scientific investigation typically is to form a hypothesis .A hypothesis is a possible answer to a scientific question. But it isn’t just any answer. A hypothesis must be based on scientific knowledge. In other words, it shouldn't be at odds with what is already known about the natural world. A hypothesis also must be logical, and it is beneficial if the hypothesis is relatively simple. In addition, to be useful in science ,a hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable. In other words, it must be possible to subject the hypothesis to a test that generates evidence for or against it, and it must be possible to make observations that would disprove the hypothesis if it really is false. A hypothesis is often expressed in the form of prediction: If the hypothesis is true, then B will happen to the dependent variable . Fleming's hypothesis might have been: "If a certain type of mold is introduced to a particular kind of bacteria growing on a plate, the bacteria will die." Is this a good and useful hypothesis ? The hypothesis is logical and based directly on observations. The hypothesis is also simple, involving just one type each of mold and bacteria growing on a glass plate. This makes it easy to test. In addition, the hypothesis is falsifiable. If bacteria were to grow in the presence of the mold, it would disprove the hypothesis if it really is false. Hypothesis Testing Hypothesis testing is at the heart of a scientific investigation . How would Fleming test his hypothesis ? He would gather relevant data as evidence . Evidence is any type of data that may be used to test a hypothesis . Data (singular, datum) are essentially just observations. The observations may be measurements in an experiment or just something the researcher notices. Testing a hypothesis then involves using the data to answer two basic questions: 1. If my hypothesis is true, what would I expect to observe? 2. Does what I actually observe match what predicted? A hypothesis is supported if the actual observations (data) match the expected observations. A hypothesis is refuted if the actual observations differ from the expected observations. Testing Fleming's Hypothesis To test his hypothesis that the mold kills bacteria , Fleming grew colonies of bacteria on several glass plates and introduced mold to just some of the plates. He subjected all of the plates to the same conditions except for the introduction of mold. Any differences in the growth of bacteria on the two groups of plates could then be reasonably attributed to the presence/absence of mold. Fleming's data might have included actual measurements of bacterial colony size, like the data shown in the data table below, or they might have been just an indication of the presence or absence of bacteria growing near the mold. Data like the former, which can be expressed numerically, are called quantitative data . Data like the latter, which can only be expressed in words, such as present or absent, are called qualitative data . Table 1.5.11.5.1: Hypothetical data of bacterial growth on plat Bacterial Plate Identification Number Introduction of Mold to Plate? 1 yes 2 yes 3 yes 4 yes 5 yes Table 1.5.11.5.1: Hypothetical data of bacterial growth on plat Bacterial Plate Identification Number Introduction of Mold to Plate? 6 no 7 no 8 no 9 no 10 no Analyzing and Interpreting Data The data scientists gather in their investigations are raw data. These are the actual measurements or other observations that are made in an investigation, like the measurements of bacterial growth shown in the data table above. Raw data usually must be analyzed and interpreted before they become evidence to test a hypothesis . To make sense of raw data and decide whether they support a hypothesis , scientists generally use statistics. There are two basic types of statistics: descriptive statistics and inferential statistics . Both types are important in scientific investigations. Descriptive statistics describe and summarize the data. They include values such as the mean, or average, value in the data. Another basic descriptive statistic is the standard deviation, which gives an idea of the spread of data values around the mean value. Descriptive statistics make it easier to use and discuss the data and also to spot trends or patterns in the data. Inferential statistics help interpret data to test hypotheses. They determine how likely it is that the actual results obtained in an investigation occurred just by chance rather than for the reason posited by the hypothesis . For example, if inferential statistics show that the results of an investigation would happen by chance only 5 percent of the time, then the hypothesis has a 95 percent chance of being correctly supported by the results. An example of a statistical hypothesis test is a t-test. It can be used to compare the mean value of the actual data with the expected value predicted by the hypothesis . Alternatively, a t-test can be used to compare the mean value of one group of data with the mean value of another group to determine whether the mean values are significantly different or just different by chance. Assume that Fleming obtained the raw data shown in the data table above. We could use a descriptive statistic such as the mean area of bacterial growth to describe the raw data. Based on these data, the mean area of bacterial growth for plates with mold is 56 mm2, and the mean area for plates without mold is 69 mm2. Is this difference in bacterial growth significant? In other words, does it provide convincing evidence that bacteria are killed by the mold or something produced by the mold? Or could the difference in mean values between the two groups of plates be due to chance alone? What is the likelihood that this outcome could have occurred even if mold or one of its products does not kill bacteria ? A t-test could be done to answer this question. The p-value for the t-test analysis of the data above is less than 0.05. This means that one can say with 95% confidence that the means of the above data are statistically different. Drawing Conclusions A statistical analysis of Fleming's evidence showed that it did indeed support his hypothesis . Does this mean that the hypothesis is true? No, not necessarily. That's because a hypothesis can never be proven conclusively to be true. Scientists can never examine all of the possible evidence , and someday evidence might be found that disproves the hypothesis . In addition, other hypotheses, as yet unformed, may be supported by the same evidence . For example, in Fleming's investigation, something else introduced onto the plates with the mold might have been responsible for the death of the bacteria . Although a hypothesis cannot be proven true without a shadow of a doubt, the more evidence that supports a hypothesis , the more likely the hypothesis is to be correct. Similarly, the better the match between actual observations and expected observations, the more likely a hypothesis is to be true. Many times, competing hypotheses are supported by evidence . When that occurs, how do scientists conclude which hypothesis is better? There are several criteria that may be used to judge competing hypotheses. For example, scientists are more likely to accept a hypothesis that: explains a wider variety of observations. explains observations that were previously unexplained. generates more expectations and is thus more testable. is more consistent with well-established theories. is more parsimonious, that is, is a simpler and less convoluted explanation. Correlation -Causation Fallacy Many statistical tests used in scientific research calculate correlations between variables. Correlation refers to how closely related two data sets are, which may be a useful starting point for further investigation. However, correlation is also one of the most misused types of evidence , primarily because of the logical fallacy that correlation implies causation. In reality, just because two variables are correlated does not necessarily mean that either variable causes the other. A simple example can be used to demonstrate the correlation -causation fallacy. Assume a study found that both ice cream sales and burglaries are correlated; that is, rates of both events increase together. If correlation really did imply causation, then you could conclude that ice cream sales cause burglaries or vice versa. It is more likely, however, that a third variable, such as the weather, influences rates of both ice cream sales and burglaries. Both might increase when the weather is sunny. An actual example of the correlation -causation fallacy occurred during the latter half of the 20th century. Numerous studies showed that women taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to treat menopausal symptoms also had a lower-than-average incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD). This correlation was misinterpreted as evidence that HRT protects women against CHD. Subsequent studies that controlled other factors related to CHD disproved this presumed causal connection. The studies found that women taking HRT were more likely to come from higher socio-economic groups, with better-than-average diets and exercise regimens. Rather than HRT causing lower CHD incidence, these studies concluded that HRT and lower CHD were both effects of higher socioeconomic status and related lifestyle factors. Communicating Results The last step in a scientific investigation is communicating the results to other scientists. This is a very important step because it allows other scientists to try to repeat the investigation and see if they can produce the same results. If other researchers get the same results, it adds support to the hypothesis . If they get different results, it may disprove the hypothesis . When scientists communicate their results, they should describe their methods and point out any possible problems with the investigation. This allows other researchers to identify any flaws in the method or think of ways to avoid possible problems in future studies. Repeating a scientific investigation and reproducing the same results is called replication . It is a cornerstone of scientific research. Replication is not required for every investigation in science , but it is highly recommended for those that produce surprising or particularly consequential results. In some scientific fields, scientists routinely try to replicate their own investigations to ensure the reproducibility of the results before they communicate them. Scientists may communicate their results in a variety of ways. The most rigorous way is to write up the investigation and results in the form of an article and submit it to a peer-reviewed scientific journal for publication. The editor of the journal provides copies of the article to several other scientists who work in the same field. These are the peers in the peer-review process. The reviewers study the article and tell the editor whether they think it should be published, based on the validity of the methods and significance of the study. The article may be rejected outright, or it may be accepted, either as is or with revisions. Only articles that meet high scientific standards are ultimately published. Review 1. Outline the steps of a typical scientific investigation . 2. What is a scientific hypothesis ? What characteristics must a hypothesis have to be useful in science ? 3. Explain how you could do a scientific investigation to answer this question: Which of the following surfaces in my home has the most bacteria : the house phone, TV remote, bathroom sink faucet, or outside door handle? Form a hypothesis and state what results would support it and what results would refute it. 4. Use the Table 1.5.11.5.1 above that shows data on the effect of mold on bacterial growth to answer the following questions A. Look at the areas of bacterial growth for the plates in just one group – either with mold (plates 1-5) or without mold (plates 6-10). Is there a variation within the group? What do you think could be possible sources of variation within the group? B. Compare the area of bacterial growth for plate 1 vs. plate 7. Does this appear to be more of a difference between the mold group vs. the no mold group than if you compared plate 5 vs. plate 6? Using these differences among the individual data points, explain why it is important to find the mean of each group when analyzing the data. C. Why do you think it would be important for other researchers to try to replicate the findings in this study? 5. A scientist is performing a study to test the effects of an anticancer drug in mice with tumors. They look in the cages and observes that the mice that received the drug for two weeks appear more energetic than those that did not receive the drug. At the end of the study, the scientist performs surgery on the mice to determine whether their tumors have shrunk. Answer the following questions about the experiment . A. Is the energy level of the mice treated with the drug a qualitative or quantitative observation ? B. At the end of the study, the scientist measures the size of the tumors. Is this qualitative or quantitative data ? C. Would the size of each tumor be considered raw data or descriptive statistics ? D. The scientist determines the average decrease in tumor size for the drug-treated group. Is this raw data, descriptive statistics , or inferential statistics ? E. The average decrease in tumor size in the drug-treated group is larger than the average decrease in the untreated group. Can the scientist assume that the drug shrinks tumors? If not, what do they need to do next? 6. Do you think results published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal are more or less likely to be scientifically valid than those in a self-published article or book? Why or why not 7. Explain why real science is usually “nonlinear”? Explore More Watch this TED talk for a lively discussion of why the standard scientific method is an inadequate model of how science is really done. Attributions 1. Rio Tinto River by Carol Stoker, NASA, public domain via Wikimedia Commons 2. Scientific Method by OpenStax, licensed CC BY 4.0 3. Alexander Flemming by Ministry of Information Photo Division Photographer, public domain via Wikimedia Commons 4. Text adapted from Human Biology by CK-12 licensed CC BY-NC 3.0