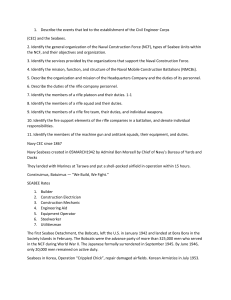

Seabees History, Organization, and Laws of Armed Conflict

advertisement