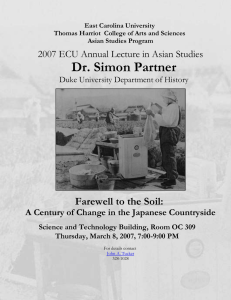

Home About Submission Guidelines Current Issue Past Issues Connections Home » Past Issues » Holding up a Lens to the Consortium of Asian American Theaters and Artists: A Photo Essay PA S T I S S U E S / V O L . 3 4 N O . 2 Holding up a Lens to the Consortium of Asian American Theaters and Artists: A Photo Essay B Y R O G E R TA N G T H E J O U R N A L O F A M E R I C A N D R A M A A N D T H E AT R E V O LU M E 3 4 , N U M B E R 2 ( S P R I N G 2 0 2 2 ) ISNN 2376-4236 © 2 0 2 2 B Y M A R T I N E . S E G A L T H E AT R E C E N T E R Artistic Statement Roger Tang has been an advocate and champion of Asian American theatre ever since he found himself a dormmate of noted playwright David Henry Hwang. Not being able to match him in talent, he decided through sheer persistence to match him as a promoter of Asian American theatre: as the creator of the Asian American Theatre Revue, one of the foremost Asian American information resources on the web, as the founder of the aa-drama listserv, a forerunning email list linking Asian American artists across the country, as a producer introducing new Asian American works to the Pacific Northwest, and as a board member for the Consortium of Asian American Theaters & Artists. Throughout all this, his guiding principle is to see what exists out there and what doesn’t. If something doesn’t exist, then he will fill the gap, whether it’s humor, legendary heroes, or Asian American bodies themselves. All photos in this essay except for Figure 3 are by Roger Tang. Figure 3 used with permission from the Consortium of Asian American Theaters & Artists (CAATA). Section I Arising at the same time as the Black Power and Third World movements of the 1960s and 1970s, the Asian American theatre movement was part of the political formation of a pan-ethnic Asian American coalition on the West Coast. Asian American theatres demand recognition of Asian Americans as inherently valuable and allow Asian American perspectives, values, and art to flourish in a way that would not be possible at primarily white institutions. As institutions, Asian American theatres meet community needs for solidarity, advocacy, and artistic expression, particularly for artists early in their careers. Still, having a home of our own is just the beginning for Asian American artists. In my work with the aa-drama listserv and the Asian American Theatre Revue, I created forums where people gather to learn what other artists were doing and meet kindred souls. Emails crisscross the country as artists network to brainstorm solutions to common problems. The Consortium of Asian American Theaters & Artists (CAATA) similarly began as a way to create these homes on a larger scale, using the listserv and the Revue to track down and assemble previously unknown artists and groups. In 1999, there was a convention in Seattle that brought together Asian American artists from Los Angeles, New York City, and other parts of the country. Then, in September 2003, six Asian American theatre companies attended a gathering sponsored by Theater Communications Group. These companies were the largest and most stable of the dozen companies that existed at that time: Pan Asian Repertory Theatre, East West Players, Ma-Yi Theater, the National Asian American Theatre Company, Second Generation, and Mu Performing Arts. These six groups began discussions to hold the first national Asian American theatre conference, which younger groups such as Los Angeles’s Artists at Play and Chicago’s Silk Road Rising were able to attend. Spearheaded by Tim Dang of East West Players, “Next Big Bang: The First Asian American Theater Conference” took place in Los Angeles in June 2006, followed by the first national festival in New York City in June 2007. This was the genesis of CAATA, a collective of Asian American theatres, leaders, and artists who collaborate to inspire learning; share resources; promote a healthy, sustainable artistic ecology; and work toward social justice, artistic diversity, cultural equity, and inclusion. Each ConFest (Conference Festival) features a wide array of o!erings that include academic panels, artists’ roundtables, staged readings, and full productions, o"en one-person shows. This palette of o!erings assured Asian American artists that they were not alone and that their feelings were valid. There were also opportunities to discuss solutions to common problems, such as combatting yellowface and diversifying a previously all-white talent pool. Conferences and festivals have since been hosted in Minneapolis (2008), New York City (2009), Los Angeles (2011), Philadelphia (2014), Ashland with the Oregon Shakespeare Festival (2016), and Chicago with DePaul University (2018). These have proven to be especially popular among young and emerging artists who seize on the opportunities ConFests create to connect with established theatres and artists from across the country. A welcome byproduct was the formation and strengthening of new, local networks that carried on the grassroots organizing ConFest promotes. Chicago began a regular series to present new works by local playwrights. Philadelphia saw the formation of the Philadelphia Asian Performing Artists group, which has now presented its own multi-day regional conference, complete with a slate of readings, panels, and festival o!erings. This sense of connection is cultivated and expanded upon by attendees a"er the physical ConFest moves to other cities. Section II ConFests enable Asian American theatre makers and scholars to connect with and reflect on history, whether directly with canonical playwrights or thoughtfully with the constituency of an ever-evolving Asian America. In the most obvious sense, leaders in the field (like David Henry Hwang, Rick Shiomi, and Rajiv Joseph) come to speak and attendees get to pick their brains about their work and the history created. Here, in Figure 1, from the 2008 ConFest in Minneapolis is a panel of longtime figures in Asian American theatre: David Henry Hwang (M. Butterfly, So" Power), Lloyd Suh (American Hwangap, The Chinese Lady), and Chay Yew (A Language of Their Own, Question 27, Question 28). Nothing beats hearing from the source that 75% of the material in Yellow Face was true events that occurred around M. Butterfly and Miss Saigon. Figure 1. Photo by Roger Tang. This sense of connection extends to more individualized exercises that link the personal to the larger events of Asian American theatre history. For example, a regular exercise at ConFest is to line up attendees by which decade they entered Asian American theatre; the groupings tend to show that most of the attendees joined very recently (leaving me and other CAATA board members in the outskirts with other “old-timers”). Another interesting exercise in the 2006 ConFest in Los Angeles saw attendees generating The Timeline, a record of events in Asian American theatre history, both in general importance and personal importance (Figure 2). This timeline is now available online (and updated) at the CAATA website and the Asian American Theatre Revue. Figure 2. Photo by Roger Tang. Finally, these connections have broadened in recent years. Asian American theatre originally centered on Japanese American, Chinese American, and Filipino American artists. Over the years, that focus has expanded to Korean Americans and Southeast Asian Americans, as immigration policies and histories changed and new artists emerged. As a matter of policy, the CAATA Board maintains the organization as a big house, welcome not only to those who want to be in coalition but also to those who choose not to be. This harkens back to the origins of the creation of Asian American identity, where Filipino Americans, Japanese Americans, and Chinese American formed coalitions that emphasized shared experiences and politics. This also reflects the voluntary nature of this identity, with each group entitled to self-determination to join or to focus on their own needs. ConFest backed this up by organizing regular pre-conference activities aimed at specific groups with whom to form connections. In 2007, pre-conference events were aimed at South Asian American artists. In 2016, the pre-conference was devoted to Middle Eastern and North African artists. For the current ConFest, CAATA is focusing on Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders as groups needing an upli" and whose issues are distinct from Asian Americans as a whole; for example, in Hawai‘i, various Asian American groups are actually settlers on indigenous land. Section III Another current that runs through CAATA and ConFest is social justice, both on stage and o!. In the industry towns of Los Angeles and New York City, much of the impetus for Asian American theatres stemmed from employment issues—casting (or lack thereof) and stereotyping on film, television, and stage. In cities such as Seattle and San Francisco, where Asian American political identity was born, issues of racial injustice were also prominent; representation on stage was seen as both a political and artistic statement. This made Asian American stages a natural home for plays like Paper Angels and Gold Watch, which dealt with the injustices inflicted on Asian Americans throughout history such as racist immigration laws and the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans. Theatre artists in all cities easily navigated the stage and the streets in matters of social justice, as many had day jobs as activists and advocates for housing and employment while taking the stage at night. Recent ConFests have seen a return to this call for social justice. In 2016 (Figure 3), ConFest attendees replicated the 1921 march in downtown Ashland Oregon by the Ku Klux Klan but replaced the Klan members with Asian Americans, African Americans, Indigenous people, and other marchers from the global majority. This was an optimal blend of the theatric and the activist. In 2018 in Chicago, ConFest attendees acted more directly and joined Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) at their invitation in a protest against the Aloha Poke chain and their attempt to trademark “Aloha” as its intellectual property (Figure 4). Figure 3. Photo by the Consortium of Asian American Theaters & Artists (CAATA). Figure 4. Photo by Roger Tang. Section IV ConFest attendees form a sense of community (that is too o"en denied in their home bases) that blossoms into something fuller once there is face-to-face contact. There is a substantial uptick in social media following meetings, as members make Facebook friends and exchange Twitter handles. Pockets of more specialized groups such as the Mixed Asian American Artists Alliance begin to sustain specialized interests, and existing geography-based groups such as the Bubble Tea group for Chicago activities and the Network for Asian American Theatre Professionals – L.A. get an influx of out-of-area members (possibly to check out potential areas where they might move). Children and families form a consistent part of the ConFest scenery (gotta start them young in theatre!), as seen in this shot (Figure 5) from the 2011 Los Angeles gathering. Discussions of theatre life with children have been consistently part of the conversation at ConFests, and of course, food always plays a part in bringing people together and bonding (Figure 6, also from the 2011 ConFest). Figure 5. Photo by Roger Tang. Figure 6. Photo by Roger Tang. Section V ConFests present fully realized works on stage, allowing Asian American artists chances to see works that have yet to reach their part of the country. With careful consideration, delegates of the CAATA Board through the ConFest Committee select a variety of work that span forms (from solo works to large casts), ethnic groups (East Asian and South Asian to Western Asian and Pacific Islanders), and subject matter (remounted Western classics to Hawaiian dance pieces to reflections on September 11, 2001). These works act as test labs for the future, not only for Asian American theatre but for drama in general. Playwrights network with each other and other ConFest attendees. Here in Figure 7, in 2011 in Los Angeles, we see playwrights Qui Nguyen (Vietgone, Disney’s Raya and the Last Dragon) and Lauren Yee (Cambodian Rock Band, King of the Yees, The Great Leap) on the panel with director Je! Liu to discuss their work. A decade later, they have gone on to win major awards and become some of the most produced playwrights in the United States. From Minneapolis in 2008, we see SIS Productions in Figure 8 produce an episode from their 20-part Sex in Seattle romantic comedy that was a smash hit running from 2000 to 2012, a clear harbinger for the success of the movie Crazy Rich Asians in 2018. Leah Nanako Winkler’s Two Mile Hollow, a parody of dysfunctional white family dramas, received its first reading in 2016 and has now played in dozens of theatres from coast to coast; Figure 9 is the cast photo of the reading in Ashland, Oregon. Figure 7. Photo by Roger Tang. Figure 8. Photo by Roger Tang. Figure 9. Photo by Roger Tang. What is presented is unpredictable but o"en signals new pathways for the field. Here in Figure 10, in New York City in 2009, we see Soo-Jin Lee and perennial ConFest artist Kristina Wong perform in APACUNTNY. And in Figure 11, we have Asian Steampunk Cowboys from 2016, as we see May Nguyen Lee and Denny Le perform a scene from The Tumbleweed Zephyr. Both of these works defy conventions of mainstream American and conventional Asian American theatre. APACUNTNY attacks the idea of the model minority by embracing enthusiastic, frank Asian American female sexuality, and The Tumbleweed Zephyr seizes tropes like the lone wolf bandit and the Wild West train robbery and reshapes them to place them squarely in the Asian American theatre canon. Shows such as these point to new directions, themes, and genres for Asian American theatres to pursue. Figure 10. Photo by Roger Tang. Figure 11. Photo by Roger Tang. Section VI ConFests remain a vital part of the future of Asian American theatre. Due to the continuing waves of the COVID–19 pandemic, ConFest has chosen a virtual presentation again in spring 2022, but the focus remains on the work of Kānaka Maoli and how Asian American artists can work with them. To fill the need for connection, there will be virtual happy hours set up to link Hawaiian theatre artists with their counterparts in the continental United States. Future ConFests remain on the agenda (perhaps ConFest will again return to Hawai‘i to learn about the lands of Indigenous artists), and CAATA will move forward to highlight di!erent parts of the North American continent, less visible aspects of Asian America, emerging artists, and other pressing new concerns. Roger Tang is Executive Director of Pork Filled Productions (Seattle, WA), the Pacific Northwest’s oldest Asian American theatre. He has introduced the region to such authors as Qui Nguyen and Carla Ching and has presented the Pacific Northwest and world premieres of nearly a dozen plays, including his own She Devil of the China Seas. He is also Secretary of the Consortium of Asian American Theaters & Artists and the editor of the Asian American Theatre Revue (www.aatrevue.com). Guest Editor: Donatella Galella Advisory Editor: David Savran Founding Editors: Vera Mowry Roberts and Walter Meserve Editorial Sta!: Co-Managing Editor: Emily Furlich Co-Managing Editor: Dahye Lee Guest Editorial Board: Arnab Banerji Lucy Mae San Pablo Burns Broderick Chow Chris A. Eng Esther Kim Lee Sean Metzger Christine Mok Stephen Sohn Advisory Board: Michael Y. Bennett Kevin Byrne Tracey Elaine Chessum Bill Demastes Stuart Hecht Jorge Huerta Amy E. Hughes David Krasner Esther Kim Lee Kim Marra Ariel Nereson Beth Osborne Jordan Schildcrout Robert Vorlicky Maurya Wickstrom Stacy Wolf Table of Contents: “Introduction to Asian American Dramaturgies” by Donatella Galella “Behind the Scenes of Asian American Theatre and Performance,” by Donatella Galella, Dorinne Kondo, Esther Kim Lee, Josephine Lee, Sean Metzger, and Karen Shimakawa “On Young Jean Lee in Young Jean Lee’s We’re Gonna Die” by Christine Mok “Representation from Cambodia to America: Musical Dramaturgies in Lauren Yee’s Cambodian Rock Band” by Jennifer Lynn Goodlander “The Dramaturgical Sensibility of Lauren Yee’s The Great Leap and Cambodian Rock Band” by Kristin Leahey, with excerpts from an interview with Joseph Ngo “Holding up a Lens to the Consortium of Asian American Theaters and Artists: A Photo Essay” by Roger Tang “Theatre in Hawai’i: An ‘Illumination of the Fault Lines’ of Asian American Theatre” by Jenna Gerdsen “Randul Duk Kim: A Sojourn in the Embodiment of Words” by Baron Kelly “Reappropriation, Reparative Creativity, and Feeling Yellow in Generic Ensemble Company’s The Mikado: Reclaimed” by kt shorb “Dance Planets” by Al Evangelista “Dramaturgy of Deprivation (없다): An Invitation to Re-Imagine Ways We Depict Asian American and Adopted Narratives of Trauma” by Amy Mihyang Ginther “Clubhouse: Stories of Empowered Uncanny Anomalies” by Bindi Kang “O!-Yellow Time vs. O!-White Space: Activist Asian American Dramaturgy in Higher Education” by Daphne P. Lei “Asian American Dramaturgies in the Classroom: A Reflection” by Ariel Nereson www.jadtjournal.org jadt@gc.cuny.eduwww.jadtjournal.org jadt@gc.cuny.edu Martin E. Segal Theatre Center: Frank Hentschker, Executive Director Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications Yu Chien Lu, Administrative Producer ©2022 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center 365 Fi"h Avenue New York NY 10016 This entry is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license. YOU MAY ALSO LIKE Published May 20, 2022 Published May 23, 2022 Dramaturgy of Deprivation (없다): An Invitation to Re-Imagine Ways We Depict Asian American and Adopted Narratives of Trauma Protected: Randall Duk Kim: A Sojourn in the Embodiment of Words There is no excerpt because this is a protected post. ON YOUNG JEAN LEE IN YOUNG JEAN LEE’S… T H E AT R E I N H A W A I ʻ I : A N “ I L L U M I N AT I O N O F … © 2023 – All rights reser ved Powered by WP – Designed with the Customizr theme People Help Groups Privacy Sites Courses Terms of Service Events Activity About Creative Commons (CC) license unless otherwise noted Built with WordPress Powered by CUNY Protected by Akismet