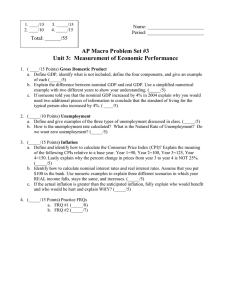

Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Introduction, GDP, Inflation, Unemployment ........................................................................................... 3 1.1 Gross domestic product ........................................................................................................................... 3 1.1.1 Calculation of GDP ........................................................................................................................... 3 1.1.2 Nominal vs Real ............................................................................................................................... 3 1.1.3 Gross national product .................................................................................................................... 4 1.1.4 Problems with GDP ......................................................................................................................... 4 1.1.5 Growth rate of GDP ......................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Unemployment rate ................................................................................................................................ 4 1.2.1 Okun’s Law ...................................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Inflation (𝝅)............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.3.1 GDP deflator .................................................................................................................................... 4 1.3.2 Consumer Price index (CPI) ............................................................................................................. 5 1.3.3 Why do they differ?......................................................................................................................... 5 2 SHORT RUN (1): Goods market ................................................................................................................. 6 2.1 The different variables............................................................................................................................. 6 2.1.1 Private consumption C .................................................................................................................... 6 2.1.2 Investment I .................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1.3 Government spending G and taxes T .............................................................................................. 6 2.2 Equilibrium .............................................................................................................................................. 6 2.2.1 Out of equilibrium ........................................................................................................................... 7 2.3 Alternative interpretation of the goods market equilibrium ................................................................... 7 2.3.1 Private savings ................................................................................................................................. 7 2.3.2 Public savings .................................................................................................................................. 7 2.3.3 Equilibrium ...................................................................................................................................... 7 3 SHORT RUN (2): Financial markets ............................................................................................................ 8 3.1 Functions of money ................................................................................................................................. 8 3.2 Money demand ....................................................................................................................................... 8 3.3 Money supply without commercial banks ............................................................................................... 8 3.3.1 Instruments of monetary policy by the central banks .................................................................... 8 3.3.2 Bonds ............................................................................................................................................... 8 3.4 4 Money supply with commercial banks .................................................................................................... 9 SHORT RUN (3): IS-LM-Model ................................................................................................................... 9 4.1 IS Relation on the goods market ............................................................................................................. 9 4.2 LM curve in the financial market ........................................................................................................... 10 4.2.1 With money supply control ........................................................................................................... 10 4.2.2 With interest rate control ............................................................................................................. 11 4.3 Combining IS and LM ............................................................................................................................. 11 4.4 Fiscal Policy in the IS-LM model............................................................................................................. 11 4.4.1 Ricardian equivalence ................................................................................................................... 12 4.5 Monetary Policy in the IS-LM model...................................................................................................... 12 4.5.1 Liquidity Trap ................................................................................................................................. 12 5 MEDIUM RUN (1): Labor Market ............................................................................................................ 13 5.1 Perfect Labor Market ............................................................................................................................ 13 5.1.1 Labor Supply .................................................................................................................................. 13 5.1.2 Labor Demand ............................................................................................................................... 13 5.1.3 Labor Market Equilibrium ............................................................................................................. 13 5.2 Labor Market dynamics ......................................................................................................................... 14 5.3 Imperfect Labor Market ........................................................................................................................ 14 5.3.1 Wage setting ................................................................................................................................. 14 5.3.2 Price setting ................................................................................................................................... 14 5.3.3 Labor market equilibrium .............................................................................................................. 15 5.4 6 Natural level of production (output potential) ...................................................................................... 15 Medium Run (2): Inflation ...................................................................................................................... 16 6.1 Equation of Exchange ............................................................................................................................ 16 6.2 Phillips Curve ......................................................................................................................................... 16 6.3 Modified Phillips Curve .......................................................................................................................... 16 6.4 Natural Rate of unemployment (NAIRU) ............................................................................................... 17 6.5 Extension of the IS-LM model ................................................................................................................ 17 6.5.1 Real Interest Rates ........................................................................................................................ 17 6.5.2 Taylor rule ..................................................................................................................................... 17 6.5.3 Risk Premium................................................................................................................................. 18 7 Medium Run (3): IS-LM-PC-model........................................................................................................... 18 7.1 PC curve ................................................................................................................................................. 18 7.2 IS-LM-PC model ..................................................................................................................................... 19 7.3 Monetary Policy .................................................................................................................................... 19 7.3.1 The CB chooses the nominal interest rate .................................................................................... 19 7.3.2 The CB chooses the real interest rate ........................................................................................... 20 7.3.3 The CB chooses the inflation rate ................................................................................................. 20 7.4 8 Fiscal policy ........................................................................................................................................... 20 Open Economy ....................................................................................................................................... 21 8.1 Open goods market ............................................................................................................................... 21 8.1.1 Nominal exchange rate ................................................................................................................. 21 8.1.2 Real exchange rate ........................................................................................................................ 21 8.1.3 Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) ...................................................................................................... 21 8.2 Open financial markets ......................................................................................................................... 22 8.2.1 Balance of Payments ..................................................................................................................... 22 9 International Macroeconomics ............................................................................................................... 23 9.1 Interest Rate Parity ............................................................................................................................... 23 9.1.1 Empirical example ......................................................................................................................... 23 9.2 Demand for goods in an open economy (IS-Curve) ............................................................................... 23 1 Introduction, GDP, Inflation, Unemployment Macroeconomics basically knows three main figures 1.1 Gross domestic product Measures the value of all final goods/services (not intermediary goods!) produced within an economy during a specific period of time (usually year) Or Measures the sum of value added in the economy during a specific period 1.1.1 Calculation of GDP 1. GDP by expenditure The GDP measures the total demand within an economy: Y = C + I + G + (X – Im) 2. (Y = Total consumption (GDP)) C: Consumption by private households (excluding buying a house (I)) I: Investments into capital goods (e.g. machines), inventories, and residential property G: Goods and services consumed by the government (however, no transfers!) X: Exports Im: Imports GDP by income The GDP is also the sum of all incomes earned within an economy (In principle, we also have to add taxes (income for the government) and subtract subsidies) GDP = labor income + capital income 3. Labor income: wages, salaries Capital income: profits, interests, dividends GDP by production GDP is the total value added in all sectors in an economy GDP = value of produced output – value of used inputs 1.1.2 Outputs: production of goods and services Inputs: raw materials., intermediate inputs Nominal vs Real Nominal GDP: quantities produced * market prices (current) Real GDP: quantities produced * prices of base year (constant prices) shows actual increase in production 1.1.3 Gross national product While the GDP follows the country territory-based principle, the GNP follows the resident principle. GNP = GDP + profits/income generated by residents abroad – profits/income generated by foreigners in the country net income and dividends from foreign assets (NIFA) 1.1.4 Problems with GDP 1.1.5 GDP flawed/incomplete o Black market not measured o Unpaid, non-market-based work not recorded (e.g. architect building for himself, unpaid housework, etc.) Questionable whether it actually measures “welfare” as in happiness Says nothing about the distribution of monetary welfare Doesn’t consider factors such as environmental quality non-monetary social costs not included in calculation Growth rate of GDP 𝑔𝑦 = 1.2 𝑌𝑡 − 𝑌𝑡−1 𝑌𝑡−1 If g > 1 GDP growth (expansion or even boom) If g < 1 GDP decline (recession, often only after two consecutive periods of negative growth) Unemployment rate 1.2.1 Ratio between number of unemployed people U and the total labor force L o Labor force = employed workers N + unemployed workers U Okun’s Law States that unemployment rate u decreases with fast GDP growth and that u increases with very slow or even negative GDP growth 1.3 Inflation (𝝅) Shows the growth rate of the price level compared to the previous price level 𝜋𝑡 = 𝑃𝑡 − 𝑃𝑡−1 𝑃𝑡−1 There are two ways to measure the price level 1.3.1 GDP deflator If the price level increases, the nominal GDP grows faster than the real GDP. Hence the ratio between those two is equal to the GDP deflator (Pt, equal to 1 in base year (GDPnom = GDPreal) Growth rate of GDP deflator inflation - Growth rate of GDPnom – Pt = Growth rate of GDPreal - GDPnom = Pt * GDPreal It is a Paasche price index, as it uses variable quantities and constant prices 1.3.2 Consumer Price index (CPI) While the GDP deflator looks at the average price of the good produced, the Consumer price index look at the average price of the good consumed more value to consumers The CPI looks at a certain basket, a selection of relevant consumer goods, and checks their prices regularly. It compares it to the base year to create an index. Hence it is calculated as follows 𝐶𝑃𝐼 = 𝐵𝑎𝑠𝑘𝑒𝑡 𝑝𝑟𝑖𝑐𝑒 𝑖𝑛 𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑖𝑜𝑑 𝑡 𝐵𝑎𝑠𝑘𝑒𝑡 𝑝𝑟𝑖𝑐𝑒 𝑖𝑛 𝑏𝑎𝑠𝑒 𝑦𝑒𝑎𝑟 However, the CPI as a such is irrelevant. What counts is its growth rate inflation It is a Laspeyres price index, as it uses constant quantities of a base year but current/variable prices 1.3.3 Why do they differ? o o o o GDP deflator doesn’t include only the goods that are consumed by the private households but also the goods that are sold to the government The GDP deflator automatically adjusts the good and the quantities whereas the CPI has this constant basket The basket of the CPI also includes foreign, imported goods (e.g. oil), whereas the GDP deflator only looks at domestically produced goods The CPI ignores the fact that consumers can substitute certain good by alternatives, hence it is usually am overestimated rate of inflation 2 SHORT RUN (1): Goods market Supply = Y + Im Total aggregate demand: Z = C + I + G + X Total income (equal to GDP): Y = T + C + S (S for savings) This chapter looks at a closed economy. Hence Exports and Imports are equal to zero. It follows that: Supply = Y and aggregate demand: Z = C + I + G 2.1 The different variables 2.1.1 Private consumption C In the real world, demand is influenced by a lot of factors. To keep it simple, we assume that demand is mainly determined by disposable income: YD YD = Y – T = C + S What that means is that the disposable income is the income minus the net taxes (T = taxes – transfers) Or in other words The consumption plus the savings It follows that the private consumption C is a function of the disposable income: C = C(YD) As it is increasing in the disposable income, the first derivative of C(YD) must be greater than zero. This marginal effect of an increase in YD is called the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) We use the following linear consumption function: C(YD) = c0 + c1YD with c0 < 0, 0 < c1 < 1 C0 = autonomous consumption (consumption of households if the disposable income is 0) C1 = marginal propensity to consume (MPC), shows by how much consumption increases if the disposable income increases by one unit 2.1.2 Investment I In this chapter, it is assumed that Investment is exogenous (hence given) 2.1.3 Government spending G and taxes T As they are both set by the government, we treat them as exogenously given 2.2 Equilibrium Supply = Demand Y = Z, hence we have Y = C + I + G, inserting the things we described above we get: Y = c0 + c1(Y – T) + I + G Remember that income equals GDP, that’s why we have a Y for income Solving for Y, we get the following equation: 𝒀= 𝟏 (𝒄 + 𝑰 + 𝑮 − 𝒄𝟏 𝑻) 𝟏 − 𝒄𝟏 𝟎 For this level of income/GDP the production is equal to demand. The formula can be divided into two parts: (𝒄𝟎 + 𝑰 + 𝑮 − 𝒄𝟏 𝑻) is autonomous spending, which is independent of the income of the economy 𝟏 𝟏−𝒄𝟏 is the multiplier. We assume that 0 < c1 < 1, such that the multiplier will always be larger than 1. The closer c1 is to 1, the larger the multiplier. What this shows is that an increase in any of the variables of the autonomous spending leads to an over proportional increase of the equilibrium output Y. 2.2.1 Out of equilibrium If supply is above demand, the excess supply will be treated as involuntary investments (into inventory). As we have seen above, this is part of the actual investment I, which again is part of the aggregate demand. Hence, thanks to this effect demand rises again to equal supply. However, firms cannot increase the inventories forever and thus this is not treated as an equilibrium. Rather, firms will eventually adjust their production/output to the planned demand form the initial situation. This brings the economy back into equilibrium. The same thing applies vice versa to excess demand. This shows that the equilibrium output is mainly determined by the demand side. Eventually, the actual production will adjust to the demand. Keynesian economics 2.3 Alternative interpretation of the goods market equilibrium Above, we have looked at supply = demand for goods and services. However, we could also look at the same relation but with supply and demand for capital, that is, savings and investments. 2.3.1 Private savings We know that private savings S are equal to the share of the disposable income that is not consumed S = YD – C Whereas disposable income is income Y minus taxes T. Hence, S=Y–T–C 2.3.2 Public savings Public savings are by definition taxes (net of transfers) minus government spending. If the government spending exceeds taxes, the government is running a budget deficit. If taxes exceed government spending, a budget surplus. Public saving = T – G 2.3.3 Equilibrium We know that Y = C + I + G Now we subtract taxes from both sides and move consumption to the left. We get Y–T–C=I+G–T The left side of the equation is simply the private saving. Hence: S=I+G–T Or, equivalently I = S + (T – G) On the left we have investments; on the right we have the sum of private and public spending. 3 SHORT RUN (2): Financial markets 3.1 Functions of money 3.2 Medium of exchange Unit of accounting Store of value Money demand We assume that people can either hold Money, that doesn’t pay any interest, but can be used to buy goods Bonds that pay interest rate i, but cannot be used to buy goods The demand of money MD is written as 𝑀𝑑 = 𝑃𝑌 ∗ 𝐿(𝑖) 3.3 P is the price level. Y is the income. Hence PY is the nominal GDP. If the prices for goods increase, more money is needed. Also, when the income increases and thus the demand for goods. L(i) is a function of the interest rate i. When the interest rate increases, the demand for money drops because bonds become more attractive. Hence, L(i) is decreasing in i. Money supply without commercial banks For money supply, we distinguish to cases. First, we look at money supply without commercial banks. In this world, money supply can directly be influenced by the central bank. We write M s, or simply M. 3.3.1 3.3.2 Instruments of monetary policy by the central banks Bonds Open market operations: buying and selling assets (i.e. ForEX, bonds, etc.) “quantitative easing” for long-term bonds Expectation management: sending a message that you will continue with low interest rates to convince companies to invest not subgame perfect Reserve rate Helicopter Money If central banks buy bonds, the demand for bonds increases and hence the price. This drops the interest rate and increases the money supply. The relationship between bond prices and interest rates can be written as follows (assuming a nominal value of 100) 100 − 𝑃𝐵 𝑖= 𝑃𝐵 Alternatively, we can write 𝑃𝐵 = 3.4 100 1+𝑖 Money supply with commercial banks Now, as we have commercial banks, the money supply is not only the money the central bank supplies (cash in circulation, CU) but also the deposits the clients have in the bank. Hence money supply is 𝑀 = 𝐶𝑈 + 𝐷 The commercial banks don’t keep all of their deposits. Rather, they further lend it to other people. The percentage which the banks keep as reserves is called θ (theta). Hence, the reserves we have are R = θ*D. The reserves are kept in “accounts” in the central bank. Together with the cash in circulation/currency CU, this constitutes the monetary base H. 𝐻 = 𝐶𝑈 + 𝑅 = 𝐶𝑈 + 𝜃𝐷 Further, we assume that b is the share of the total money supply which is kept as currency CU. 𝐶𝑈 = 𝑏𝑀 (b-1) then constitutes the share of money that is held as deposits. 𝐷 = (1 − 𝑏)𝑀 We can write: 𝐻 = 𝑏𝑀 + 𝜃(1 − 𝑏)𝑀 Solving this equation for the money supply M, we get M as a multiplier of the monetary base H: 𝑀= 1 ∗𝐻 𝑏 + 𝜃(1 − 𝑏) This is the so-called money supplier What is says is that if the monetary base increases by a certain amount, the actual money supply increases by even more. 4 4.1 SHORT RUN (3): IS-LM-Model IS Relation on the goods market Before, we said that for equilibrium in the goods market we have the Is relation (investments = savings) 𝐼 = 𝑆 + (𝑇 − 𝐺) Now we change the assumption that investments are given. We say they are dependent on two factors: Production Y: If a firm produces more, it needs higher investments Interest rate i: if the interest rate rises, the Investments go down 𝐼 = 𝐼(𝑌, 𝑖) Hence, for every given Production and Interest rate, we have an equilibrium in the goods market. If the interest rate increases, the GDP Y decreases, mainly due to the lower investments. Hence the so called IS-curve is downwards sloping: The slope of the curve is determined by how strongly demand reacts to changes in interest rates. The position of the curve is determined by the exogenous parameters c 0,c1, G and T. All changes that increase the GDP shift the curve to the right (e.g. higher government spending) 4.2 4.2.1 LM curve in the financial market With money supply control We know that for equilibrium in the money market the following equation holds: 𝑀 = 𝑃𝑌 ∗ 𝐿(𝑖) If we divide both sides by the price index P, we get that real money supply = real money demand 𝑀 = 𝑌 ∗ 𝐿(𝑖) 𝑃 This step is important, as in the goods market the income is in real terms too. Now, we know that, for a given real money supply, the equilibrium depends on the income/GDP Y and the interest rate. The LM-curve depicts all the combinations of Y and i for which the money market is in equilibrium. The slope of the LM-curve is determined by the effect of an increase of interest rates on the demand Y The position of the curve is dependent on the real money supply, hence either P or the nominal money supply M. If the real money supply increases, the curve shifts to the right. 4.2.2 With interest rate control In case of interest rate control, the central bank simply adjusts the money supply in a way that the interest rate stays constant. Thus, the LM-curve is simply denoted as 𝑖 = 𝑖0 The LM-curve looks like this 4.3 Combining IS and LM The combination of Y and i that satisfies this set of equations, show us the equilibrium in the IS-Lm model: 𝑌 = 𝐶(𝑌𝑇 ) + 𝐼(𝑌, 𝑖) + 𝐺 𝑀 = 𝑌 ∗ 𝐿(𝑖) 𝑜𝑟 𝑖 = 𝑖0 𝑃 The graph on the right Is more relevant as it shows the LM-curve with interest rate control 4.4 Fiscal Policy in the IS-LM model Fiscal policy is a term used for changes in G and T. It affects the IS-curve, not the LM-curve Assume G is increased. The demand increases. Hence also Money demand. With interest rate control (left graph), the central bank will increase money supply to match the demand. With money supply control, the central bank would increase the interest rate to match the money demand with the given supply. The rising interest rates reduce investments. Hence the increase of GDP is smaller for money supply control than for interest rate control. 4.4.1 Ricardian equivalence The idea behind Ricardian equivalence is that if the government spends more than it receives in revenue and thus goes into deficit, people will realize that they will have to pay more taxes in the future to repay the debt. As a result, they will reduce their current consumption and increase their savings to prepare for higher future taxes. What that implies is that financing government spending via current tax increases or without tax increases does not make any difference, because the latter case would simply lead to future tax increases and thus reduce current consumption. 4.5 Monetary Policy in the IS-LM model Monetary policy encompasses all the actions that the central bank takes in order to change the equilibrium: change in interest rate/change in money supply. Both shift the LM curve. 4.5.1 Liquidity Trap If the central bank has consecutive measures of expansionary monetary policy, they will eventually end up at an interest rate close to 0. If they further increase money supply or lower the interest rate, it will never go below 0. This is because as soon as the interest rate reaches zero, the households will simply hold all their money in cash, hence money demand is infinite (IS-curve goes to infinity). If no one holds bonds, the interest rate is de facto 0. Households can thus avoid negative interest rates by simply holding cash. Hence further expansionary policy would have zero effect. This is called the liquidity trap. 5 MEDIUM RUN (1): Labor Market So far, we have implicitly assumed constant prices for the goods market. We assumed that firms can simply adjust the supply to the demand. However, in the real world there is limits to that. Namely, resources are scarce, especially the resource labor. We denote the following variables: Labor force L: all individuals participating in the labor market Employed N: the part of the labor force that is employed Unemployed U: all people that would like a job but don’t have one Unemployment rate u: ratio between unemployed U and the labor force L 𝑢= 5.1 𝑈 𝑁 = 1− 𝐿 𝐿 Perfect Labor Market Assuming a labor market with many sellers and many buyers. 5.1.1 Labor Supply The Labor Supply is determined by the utility maximization of the households. They can choose between Consumption and Leisure. The utility function of a household thus depends positively on consumption, and negatively on labor supply N U (C, N) In order to maximize it, it must be solved mathematically. We find the marginal rate of substitution, which must be equal to the price ratio: − 𝑈𝑁 (𝐶, 𝑁) 𝑊 = 𝑈𝐶 (𝐶, 𝑁) 𝑃 The marginal utility of another hour worked, UN(C,N), is negative! 5.1.2 Labor Demand In the perfect market, firms observe the real wage, W/P, and decide how much labor N they want to hire. Their goal is profit maximization. The profits are denoted as the difference between revenues and the wage: 𝑃𝑟𝑜𝑓𝑖𝑡 = 𝑃 ∗ 𝐹(𝑁) − 𝑊𝑁 Taking the first order condition to find the profit maximum, we find that the marginal product of labor must be equal to the real wage: 𝑊 = 𝐹𝑁 (𝑁) 𝑃 5.1.3 Labor Market Equilibrium The real wage adjusts such that demand and supply are equal. The individuals who don’t have a job in the perfect labor market equilibrium prefer not to work voluntary unemployment (natural rate of unemployment) Fixed wages can lead to involuntary unemployment. 5.2 Labor Market dynamics What the perfect market doesn’t consider is that it takes time for an unemployed worker to find a job, likewise for a firm to find a new worker. Out of the employed workers N, the share p loses its job in period t. Thus, p*N workers enter unemployment in each period. Out of the unemployed workers U, the share s finds a new job in period t. This, s*U people leave unemployment each period. ∆𝑈 = 𝑝𝑁 − 𝑠𝑈 In an equilibrium, ∆𝑈 stays constant (∆𝑈 = 0): 𝑠𝑈 = 𝑝𝑁 If we do some rewriting, knowing that 𝑢 = 𝑈 𝑈+𝑁 , we find that the unemployment rate is equal to: 𝑢= 5.3 5.3.1 𝑝 𝑝+𝑠 Imperfect Labor Market Wage setting The wage setting equation depends on various factors. If unemployment is lower, wages are higher because workers are in a better position for bargaining. Wages are decreasing in u. Also, wages are increasing in z. Z includes a lot of factors. 𝑊 = 𝐹(𝑢, 𝑧) 𝑃 5.3.2 Price setting We know how the wages are set. Now we want to know how the prices are set. These depend on the production cost of the firm, which in turn depend on wages. We assume that each worker produces output A. Thus, a firm’s output is equal to: 𝑌 =𝐴∗𝑁 We know that firms usually add a mark-up to their production cost. This mark-up is denoted as follows: 𝜇=− 1 1+𝜀 Through differentiation we get to the profit maximization, and we obtain the price setting equation to be: 𝑊 𝐴 = 𝑃 1+𝜇 5.3.3 Labor market equilibrium In the equilibrium, the real wages from the price setting must be equal to the one from the wage setting: 𝐹(𝑢𝑛 , 𝑧) = 𝐴 1+𝜇 Where un is the natural rate of unemployment: 𝑢𝑛 (𝑧, 𝜇) It increases in both factors 5.4 Natural level of production (output potential) Using the natural rate of unemployment, one can deduce the natural rate of employment: 𝑁𝑛 = 𝐿(1 − 𝑢𝑛 ) The natural level of production is thus 𝑌𝑛 = 𝐴 ∗ 𝑁𝑛 (𝑧, 𝜇) 6 6.1 Medium Run (2): Inflation Equation of Exchange The velocity of money shows, how often each unit of money is spent in one year: 𝑉= 𝑃𝑌 1 = (𝑖𝑛𝑣𝑒𝑟𝑠𝑒 𝑜𝑓 𝐿𝑀 𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑣𝑒) 𝑀 𝐿(𝑖) We can rewrite it to get the equation of exchange 𝑀𝑉 = 𝑃𝑌 Then we take the total differential. Now, through some remodeling and assuming that the change in velocity (dV) is constant, we obtain that the growth rate of prices (= inflation) is equal to the difference between the growth rate of money supply and the real economic growth: 𝑑𝑃 𝑑𝑀 𝑑𝑌 = − 𝑃 𝑀 𝑌 6.2 Phillips Curve Basically, the Phillips curve shows the relationship between unemployment rate and inflation. If we substitute the wage setting relation from above into the price setting relation, we get: 𝑃𝑡 = 𝑃𝑡𝑒 (1 + 𝜇) ∗ 𝐹(𝑢𝑡 , 𝑧) Dividing both sides by Pt-1 , we find 𝑃𝑡 𝑃𝑡𝑒 (1 + 𝜇) ∗ 𝐹(𝑢𝑡 , 𝑧) = 𝑃𝑡−1 𝑃𝑡−1 Using the definition of the inflation, this gives us the Phillips Curve: 1 + 𝜋𝑡 = (1 + 𝜋𝑡𝑒 ) ∗ (1 + 𝜇) ∗ 𝐹(𝑢𝑡 , 𝑧) However, this is a bit complicated to understand. Assume, 𝐹(𝑢𝑡 , 𝑧) = 1 − 𝛼𝑢𝑡 + 𝑧. Through some tricks, we will end up with this (counts only for small values): 𝜋 = 𝜋 𝑒 + 𝜇 + 𝑧 − 𝛼𝑢𝑡 This is an easier version of the Phillips Curve. Note: The traditional Phillips Curve assumes inflation expectations of zero! 6.3 Modified Phillips Curve The modified Phillips Curve assumes adaptive inflation expectations. What that means is that the expected inflation of year t is somewhat related the actual inflation from the previous year t-1. Additionally, the parameter 𝜃 is introduced, describing how strongly the previous inflation affects the expectations: 𝜋𝑡 − 𝜃𝜋𝑡−1 = 𝜇 + 𝑧 − 𝛼𝑢𝑡 If 𝜃 = 1, the expected inflation of year t is exactly equal to the inflation of the preceding year. This is what happened since the 1970s. This modified Phillips Curve looks like this: 𝜋𝑡 − 𝜋𝑡−1 = 𝜇 + 𝑧 − 𝛼𝑢𝑡 This represents reality more than the “traditional” Phillips curve. Namely, in the 1970s you had high inflation as well as high unemployment (= stagflation). How is this possible, assuming the traditional Phillips curve? This is where the modified version steps in. Changes in the expectations lead to an upwards shift of the Phillips curve and thus high inflation and high unemployment are both possible. 6.4 Natural Rate of unemployment (NAIRU) In the labor market chapter, the natural unemployment rate was already discussed. However, it can also be looked at from the point of view of the Phillips curve. We know that at the natural unemployment rate, the economy is neither in a boom nor in a recession. In this medium run equilibrium, the inflation must be equal to the inflation expectation. If we substitute it into the Phillips curve, we get: 𝜋 − 𝜋 𝑒 = 𝜇 + 𝑧 − 𝛼𝑢𝑡 0 = 𝜇 + 𝑧 − 𝛼𝑢𝑡 The unemployment rate in this equation is the natural rate, as we are in the medium run equilibrium: 𝑢𝑛 = 𝜇+𝑧 𝛼 As we now know that 𝛼𝑢𝑛 = 𝜇 + 𝑧, we can rewrite the whole Phillips curve as: 𝜋 = 𝜋 𝑒 + 𝛼𝑢𝑛 − 𝛼𝑢𝑡 𝜋 = 𝜋 𝑒 + 𝛼(𝑢𝑛 − 𝑢𝑡 ) This gives us the Phillips dependent on the difference between natural and actual unemployment The NAIRU corresponds to the natural rate of unemployment, that is, to the unemployment rate at which price and wage decisions are consistent. 6.5 6.5.1 Extension of the IS-LM model Real Interest Rates So far, as we have ignored the existence of inflation, we only assumed a real interest rate in the IS-LM model. Now, we consider this effect by differentiating between: Real interest rate (r) determining the real investments I on the goods market Nominal interest rate (i) determining the nominal money demand on the money market Thereby, the Fisher equation tells us that the real interest rate is approximately the nominal rate minus expected inflation. 6.5.2 Taylor rule So far, we have assumed that the central bank, no matter the output Y, always changes money supply to maintain a certain interest rate. However, in real life, central banks do care about the output. Namely, if the output is above its natural level the central banks increase the nominal rate to avoid the economy to overheat. Same counts vice versa. Thereby, price stability serves as the overarching goal. Hence, if inflation is above target, interest rates will be increased. This usually goes hand in hand with the higher output Y described above. Thus, in order to determine the central bank’s target interest rate, the Taylor Rule gives us this formula: 𝑖𝑡 = 𝑟𝑡 + 𝜋𝑡 + 𝑎(𝜋𝑡 − 𝜋 ∗ ) + 𝑏(𝑌𝑡 − 𝑌𝑛 ) 6.5.3 Risk Premium So far, we have assumed that all assets and investments are completely risk free and thus traded at the same interest rate. However, some are riskier than others leading to investors demanding a higher return for their risk. This risk premium is denoted by the letter “x”. It can be calculated by: 𝑥= (1 + 𝑟)𝑝 1−𝑝 Whereby r refers to the risk free rate and p to the probability of the investment plus interest to be paid back. The new IS-LM model is: 𝑌 = 𝐶(𝑌 − 𝑇) + 𝐼(𝑌, 𝑟 + 𝑥) + 𝐺 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑟 = 𝑖0 − 𝜋 𝑒 An increase in the risk premium can be seen by a downward shift of the IS curve. 7 Medium Run (3): IS-LM-PC-model We need to rewrite the Phillips Curve in a way, so it fits the IS-LM model. Namely, output must be included. As we know, there is a direct relationship between output Y and the unemployment rate. Thus, there must also be a relation between output and inflation. This gives us our PC curve 7.1 PC curve The PC curve show how a change in production affect a change in inflation. We know from above that: 𝜋 = 𝜋 𝑒 + 𝛼(𝑢𝑛 − 𝑢𝑡 ) If we assume that Y = N (thus A=1), we find that 𝑌 = 𝑁 = 𝐿(1 − 𝑢) 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑌𝑛 = 𝑁𝑛 = 𝐿(1 − 𝑢𝑛 ) The output gap is then given by 𝑌 − 𝑌𝑛 = 𝐿(1 − 𝑢) − 𝐿(1 − 𝑢𝑛 ) = 𝐿(−𝑢 + 𝑢𝑛 ) 𝑙𝑒𝑎𝑑𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑡𝑜 𝑢𝑛 − 𝑢 = 𝑌 − 𝑌𝑛 𝐿 This we can plug in for (un – u) in our modified Phillips curve and get the PC curve: 𝜋 − 𝜋𝑒 = 7.2 𝛼 (𝑌 − 𝑌𝑛 ) 𝐿 IS-LM-PC model In our medium run equilibrium, the following holds: 1. 2. 3. 4. 7.3 Production is equal to natural: 𝑌 = 𝑌𝑛 Unemployment is equal to natural: 𝑢 = 𝑢𝑛 Expected inflation is equal to actual inflation: 𝜋 = 𝜋 𝑒 Real interest rate is equal to the natural rate Monetary Policy There are three strategies the central bank can pursue when faced with expansionary policy. 7.3.1 The CB chooses the nominal interest rate In this case, after the expansionary policy interest rate drop, the central bank stays with this exact nominal interest rate. Due to the expansionary policy, inflation rises. Eventually, consumers will adjust their inflation expectations to the new inflation. That implies that the real interest rate must decrease (see Fischer Equation). Therefore, the LM curve (which depicts the real interest rate) shifts downwards, leading to even stringer expansionary effects ( TEUFELSKREISLAUF) 7.3.2 The CB chooses the real interest rate In this case, the increased inflation expectations must be compensated by an increase in nominal rates. This, so it reaches the level of the stimulating real rate chosen for the expansionary policy. At this level (being expansionary), inflation is increasing. Due to the constantly adjusting expectations, nominal rates must be increased again ( TEUFELSKREISLAUF) 7.3.3 The CB chooses the inflation rate This is the only way that the CB does not cause inflation to rise continuously. In the short run, the economy is stimulated. However, at some point the nominal rate is adjusted in such a way that it matches the natural rate again. This keeps inflation at a constant level, but higher than before the expansionary measures. 7.4 Fiscal policy In case of fiscal policy, say increased government spending, a very interesting effect can be observed. Therefore, we assume a central bank that chooses the inflation rate (see 7.3.3). Namely, if G increases the IS curve shifts to the right. Y goes beyond natural, thus inflation is higher. As the central bank wants to keep the inflation at its chosen rate, it will react to this increase in inflation by raising the nominal rate such that the real interest rate reaches neutral again. The G, however, has still increased. But output is not bigger than before as it is back to natural. Thus, something in the IS equation must’ve decreased INVESTMENTS This is because the neutral rate is now higher than before. As we are at neutral level in the medium-run equilibrium, the real interest rate is also higher than before. Thus, investments must be lower. This is known as the crowding out effect Government spending has crowded out private investments! 8 Open Economy From now on, we will no longer assume that imports and exports are equal to zero. 8.1 Open goods market If the net exports are positive, then our country has a trade surplus If the net exports are negative, then our country has a trade deficit Now that the economy is not closed, individuals can choose between domestic and foreign goods. This decision is dependent on the price of domestic goods relative to the price of foreign goods ( exchange rate). Thereby, we distinguish between real and nominal exchange rate 8.1.1 Nominal exchange rate The nominal exchange rate E is simply the rate at which currencies are exchanged. It is defined as the price of the domestic currency in terms of foreign currency. Nominal depreciation: E becomes smaller, currency less expensive Nominal appreciation: E becomes bigger, currency more expensive 8.1.2 Real exchange rate The real exchange rate 𝜀 is the price of domestic goods in terms of foreign goods. For example, if 𝜀 = 1, foreign countries pay exactly one unit of their goods for one unit of ours. 𝜀= EP 𝑃∗ Where P* is the foreign price level Usually, the real exchange rate considers the relative price of all foreign goods in terms of all domestic goods. Therefore P* as well as P is usually indicated by the GDP deflator. Real depreciation: 𝜀 becomes smaller, foreign countries must pay fewer units of their goods for one of ours. Real appreciation: 𝜀 becomes bigger, foreign countries must pay more units of their goods for one of ours. Note: the real exchange rate itself is not super interesting, but the change in it! 8.1.3 Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) PPP is based on the law of price. It states that identical goods should have the same price, no matter where they are bought. In other words, 𝜀 = 1 exact purchasing power parity This exact PPP, however, only holds under three assumptions: 1. 2. 3. Zero transportation costs No trade barriers No regulations Further effects can be observed: 4. Rich countries usually have higher prices Penn effect 5. Non-tradeable goods (e.g. hairdresser) must be produced in the domestic country itself at high wages (high wages because of highly productive export industry) – but the productivity advantage is usually lower than in the export-industry Balassa-Samuelson effect Although exact PPP never holds, it can be used for comparison between countries. Thereby, one basket of goods is looked at and compared between countries. For each country a price for the basket is determined. Based on the price difference, the PPP exchange rate can be determined. Thus, it is the exchange rate at which purchasing power parity would hold (𝜀 = 1) 8.2 Open financial markets Not only goods and services can be traded internationally, but also capital. If a Swiss person buys stocks or other assets from a firm abroad, or gives a loan to some foreign firm (e.g. bond), this is called a capital export. Accordingly, capital imports exist. Capital Exports – Capital Imports = Net Capital Exports It is important to note the relationship between open financial and open goods markets. Namely, if a country is running a trade deficit, it can only do so if it receives a “loan” from the other countries. Thus, it must also be running on negative net capital exports. 8.2.1 Balance of Payments All the flows of goods and services as well as the flows of capital are reported in the balance of payments. It is divided into two accounts: Current Account and Capital Account Both accounts have to be equal! Current Account The current account is calculated as follows: 𝐸𝑥𝑝𝑜𝑟𝑡𝑠 − 𝐼𝑚𝑝𝑜𝑟𝑡𝑠 = 𝑁𝑒𝑡 𝐸𝑥𝑝𝑜𝑟𝑡𝑠 + 𝑖𝑛𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑒 𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑒𝑖𝑣𝑒𝑑 𝑓𝑟𝑜𝑚 𝑎𝑏𝑟𝑜𝑎𝑑 − 𝑖𝑛𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑒 𝑝𝑎𝑖𝑑 𝑡𝑜 𝑜𝑡ℎ𝑒𝑟 𝑐𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑒𝑠 A positive current account implies a trade surplus (e.g., Switzerland) Capital Account The capital account reports all changes in foreign holdings of domestic assets minus changes in domestic holdings of capital abroad. If it is positive, it implies that other countries invest in country A’s assets more than country A invests in other countries. Negative capital account (trade deficit) must be financed through positive capital account balance (net capital flows) 9 9.1 International Macroeconomics Interest Rate Parity Even more important than imports and exports for the exchange rate are financial investments in different countries. If I want to buy a German bond, I have to first buy Euros. If I invest one franc in German bonds now, 1 in one year I’ll have 𝐸𝑡 (1 + 𝑖 ∗ ) in Euros, or 𝐸𝑡 (1 + 𝑖 ∗ ) ∗ in francs. 𝐸𝑡+1 In an equilibrium of the financial markets, the money I get in Switzerland after one year must be equal to the money I get in Germany. This is because if one country would pay higher interest rate, everyone would buy it, which again would increase the prices and drop the interest rates such that they’re equal again. Thus, the following equation must hold. It is called (uncovered) interest parity: (1 + 𝑖) = (1 + 𝑖 ∗ ) 𝐸𝑡 𝑒 𝐸𝑡+1 Note that we now used expected exchange rate for the next year, because at this moment, we couldn’t know what the exchange rate will be in a year! For small values, we can simplify this relation to 𝑖 ≈ 𝑖∗ − Thereby, the last term 𝑒 (𝐸𝑡+1 −𝐸𝑡 ) 𝐸𝑡 𝑒 (𝐸𝑡+1 − 𝐸𝑡 ) 𝐸𝑡 is the expected growth rate of the nominal exchange rate E 𝑒 In contrast, the covered interest parity uses the forward rate instead of 𝐸𝑡+1 9.1.1 Empirical example From the uncovered interest parity relation, we can derive that if the domestic interest rate is lower than the foreign interest rate, the difference is the appreciation of the domestic currency. We get compensated for the lower interest rate in Switzerland by the appreciation of the Swiss franc. For example, we can observe that for a 10 year Swiss government bond we get 1.1%, whereas for US government bonds we get 3.6%, Thus there must be a 2.5% yearly appreciation of the Swiss franc, if the interest parity holds. 9.2 Demand for goods in an open economy (IS-Curve) Demand for domestic goods: 𝐼𝑀 𝜀 𝐼𝑀 Whereby refers to the imports in units of domestic goods (that’s why real exchange rate). 𝑍 =𝐶+𝐼+𝐺+𝑋− 𝜀 𝐷𝐷 = 𝐶 + 𝐼 + 𝐺 refers to the domestic demand 𝐴𝐴 = 𝐶 + 𝐼 + 𝐺 − 𝐼𝑀 refers to the domestic demand for domestic goods Imports increase in domestic income Y and in the real exchange rate. Thus: 𝐼𝑀 = 𝐼𝑀(𝑌, 𝜀) Exports increase in foreign income Y* and decrease in the real exchange rate. Thus: 𝑋 = 𝑋(𝑌 ∗ , 𝜀) 9.2.1 Equilibrium in the Open Goods Market The goods market is in equilibrium when the domestic production Y is equal to the demand for domestic goods Z (again, take 45° line) 𝑌 = 𝑍 = 𝐶(𝑌 − 𝑇) + 𝐼(𝑌, 𝑟 + 𝑥) + 𝐺 + 𝑁𝑋(𝑌, 𝑌 ∗ , 𝜀) increase in domestic demand increases Y, and reduces NX (as imports get bigger) increase in foreign demand increases Y, and increases NX (as exports increase) 9.3 Marshall-Lerner condition The Marshall-Lerner condition is about the effect of a decrease in the real exchange rate 𝜀 on the net exports. As we know, exports depend negatively on 𝜀, while imports depend positively on 𝜀. Thus, if the real exchange rate decreases, exports go up, while the imports decrease. However, we also know that a decrease in 𝜀 leads to an increase in prices of the imports in terms of domestic 𝐼𝑀 goods ( ). Thus, while we import less, the prices for these imports are more expensive, which again increases 𝜀 imports in a way (quantitatively). So the question arises: What is the net effect? Because you have a positive quantity effect (in terms of NX), but a negative price effect. The Marshall-Lenner condition states that the net exports, NX, increase if the real exchange rate 𝜀 depreciates (decreases) reduce trade deficit by depreciating 𝜀 9.4 Implications for government intervention A goal of the government is to reduce the trade deficit. As we have seen above, it can do that by depreciating 𝜀. However, this would also increase Y. Shall the government not wish for an increase in Y, it can reduce that effect by reducing government spending. What happens is that the government was able to reduce the trade deficit, while keeping the GDP at its original level. 9.5 IS-LM model For the IS curve: - Real depreciation and increase of Y* increase NX IS curve shifts to the right Appreciation and decrease of Y* decrease NX IS curve shifts to the left LM curve not looked at! 9.6 Investment equals Savings in the open economy? By rearranging, we obtain: 𝑁𝑋 = 𝑆 + 𝑇 − 𝐺 − 𝐼 In other words: Net exports are equal to the sum of private and public savings minus the domestic investments. That means that if a country has a current account surplus (NX > 0), the savings are higher than the domestic investments. Hence, it must be that the country invests (gives loans) in other countries. If a country is running a deficit, savings are lower than domestic investment. Hence, it must be that the country receives loans (investments) from abroad If domestic investments increase, then either domestic savings must increase or NX must decrease A country that increases its government deficit must have increasing private savings, or decreasing investments, or decreasing net exports. A country with high savings either has high domestic investments or a high current account surplus 10 Growth 10.1 What is growth and why is it important? In the medium run, we have recessions and boom phases. If you look at it in the bigger picture, an increasing trend line can be observed. This trend line reflects the development of the potential output in an economy. What follows is that long term growth has nothing to do with the demand side, but with the supply side. The fact that this line is upwards sloping cannot be taken for granted. Only since recently such a development can be observed, and that counts only for the richer countries! It is however very important that we have long-term growth rather than stagnation. First, per capita income correlates strongly with life expectancy, child mortality rates, or education. Second, in a stagnation economy A can only become richer if B becomes poorer (zero sum game), while in a growing economy A can become richer without B suffering a loss. This is important for the societal and political climate. 10.2 Theoretical Growth Model: Solow In the long term, it is all about the aggregate output/production Y. The Solow model assumes that Y is defined by two factors only: capital K and labor N. 𝑌 = 𝐹(𝐾, 𝑁) This production function satisfies some very relevant properties: 1. Constant returns to scale: If we double the amount of K and N, we also double Y 𝜆𝑌 = 𝐹(𝜆𝐾, 𝜆𝑁) 2. Decreasing marginal product: If we increase K or N by 1, Y increases. If we increase K or N further, Y increases by less 𝑓𝐾′ > 0 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑓𝐾′′ < 0 𝑓𝑁′ > 0 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑓𝑁′′ < 0 With these properties we can rewrite our production function to get to the capital per worker (capital intensity) and the output per worker 𝑘= 𝐾 𝑌 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑦 = 𝑁 𝑁 From this, a production function can be derived relating capital intensity to output per worker 𝑌 𝐾 = 𝑓( ) 𝑁 𝑁 It looks like this So how can we increase output per worker (i.e. GDP per capita)? 1. 2. If the capital per worker increases movement along the curve If productivity increases upwards shift of the curve Hence growth can be generated either through capital accumulation or through technological progress. 10.3 Growth through Capital Accumulation This is where the Solow model sees itself. Namely, it describes growth as a result of capital accumulation. It is an exogenous growth model. Hence, N is constant and there technological progress is exogenous. Underlying is a very simple cycle. With my capital stock K, I can produce output Y today. This output translates into income, of which I can save a portion s, which lead to my investments I. Of these investments, a part d gets lost due to depreciation of my existing capital K. The rest is added to my capital K, such that: 𝐾𝑡+1 = 𝐾𝑡 + ∆𝐾𝑡 = 𝐾𝑡 + (𝐼𝑡 − 𝛿𝐾𝑡 ) ∆𝐾𝑡 = 𝐼𝑡 − 𝛿𝐾𝑡 = 𝑠𝑌𝑡 − 𝛿𝐾𝑡 Thus, the change in capital stock per worker (capital intensity) is equal to the savings per worker minus the depreciation per worker: ∆𝐾𝑡 𝑌𝑡 𝐾𝑡 =𝑠 −𝛿 𝑁 𝑁 𝑁 At the point where the savings per worker are higher than the depreciation the capital stock is still growing. At the point where depreciation surpasses savings the capital stock is decreasing. Hence, the long term equilibrium is where the growth of capital stock is zero, or, in other words, savings are equal to depreciation. As 𝑌𝑡 𝑁 𝐾 = 𝑓( 𝑡) we can say that for the capital intensity the steady state is where: 𝑁 𝐾𝑡 𝐾𝑡 𝑠𝑓 ( ) = 𝛿 𝑁 𝑁 10.4 Golden Rule We see that by increasing the savings rate we can increase our output per capita, thus our steady state. However, we should also keep in mind that if we save more, less will be spent thus GDP is also partly negatively affected. So, what is the optimal savings rate? The optimal savings rate is where our consumption is maximal. That is, the difference between the production function and the investment function is maximal in the steady state. Mathematically speaking, the slope of the depreciation curve (depreciation rate) must be equal to the slope of the production function 𝐾𝑔𝑜𝑙𝑑 𝑓′ ( )=𝛿 𝑁 10.5 Growth Accounting with a Cobb Douglas Function 𝑌 = 𝐾 𝛼 𝑁 𝛼−1 Just memorize this formula for all growth accounting exercises: 𝑔𝑌 = 𝑔𝐴 + 𝛼𝑔𝐾 + (1 − 𝛼)𝑔𝑁 11 The Solow Model but extended with Productivity and Population Growth In the previous chapter, we have said that population stays constant and productivity is exogenous thus only leads to a shift of the production curve. In reality, population and productivity are both constantly growing. We extend our model: 𝑌 = 𝐹(𝐾, 𝐴𝑁) Where A is a factor for productivity. - Population N grows each period by gN percent Productivity A grows each period by gA percent - Thus, capital K grows each year by 𝑔𝐾 = 𝑔𝑘 + 𝑔𝑁 + 𝑔𝐴 = (𝐼−𝛿𝐾) 𝐾 In the steady state, the capital growth per effective worker gk must be equal to zero. Hence, we write: 𝑔𝐾 = 𝑔𝑁 + 𝑔𝐴 The actual capital must grow at the same rate as population and productivity to maintain the steady state. This means that Investments must be exactly high enough to maintain the capital per effective worker. We find it with the following condition: 𝑔𝑁 + 𝑔𝐴 = (𝐼 − 𝛿𝐾) 𝐾 𝐼 = (𝛿 + 𝑔𝑁 + 𝑔𝐴 ) ∗ 𝐾 𝐼 = (𝛿 + 𝑔𝑁 + 𝑔𝐴 ) ∗ 𝑘 𝐴𝑁 11.1.1 Growth rates in the steady state In the steady state, the following growth rates apply: Capital per effective worker 0 Output per effective worker 0 Capital per worker gA Output we worker gA Productivity A gA Labor N gN Effective Labor AN gA + gN Capital K gA + gN Production Y gA + gN 11.1.2 Golden Rule For the golden rule, see above, the slope of the production function must be equal to the slope of the breakeven investments 𝛿 + 𝑔𝑁 + 𝑔𝐴 = 𝛼 ∗ 𝑘 𝛼−1 This also translates into the following 𝑠𝑔𝑜𝑙𝑑 = 𝛼