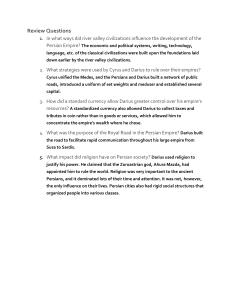

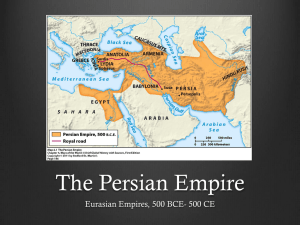

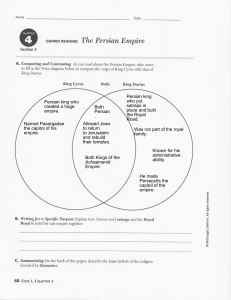

Slide 1 The Persian Empire was a major political power in the Near East in the 6th and 5th centuries BC. This empire’s reach had extended to Ionia and had begun to threaten Europe across the Hellespont. When the Ionian Greeks attempted to throw off their Persian overlords, the Athenians aided them. After the rebellion failed, the Persians reasserted their power in Ionia and decided to take vengeance upon Athens for their role in the rebellion. The third king of Persia, Darius I, launched a naval invasion that landed on the plain of Marathon to the north of Athens. Despite being outnumbered, the heavily‐ armored hoplites proved that they were a superior fighting force and soundly defeated the Persian invaders. Although this was not to be the last Persian invasion, Athens’ victory gave them confidence and helped to propel Athens into the golden age of the Classical period. Slide 2 By the fifth century BC, Persia was a massive empire that extended from the Mediterranean east all the way to India. The capitol was the city of Susa to the north of the Tigris River and close to the modern Persian Gulf. This empire was the successor of the Babylonian and Median Empires, but the Persians had continued to aggressively expand beyond the borders of those earlier empires. A Persian named Cyrus was responsible for beginning a rebellion from within the Persian province of the empire of the Medes. In 550, he conquered Media and became the first king of the Persian Empire. This week you will begin reading extensively from the Histories of the Greek historian Herodotus. Herodotus’ main goal is to describe the relations between the Greeks and the Persians, whom he calls the barbarians (the Greek term barbaroi is used of anyone who does not speak Greek; “barbaroi” refers to the odd sounds that non‐Greek speakers would make, “bar, bar, bar, bar”). Slide 3 Herodotus is especially interested in how the Ionian Greeks came under Persian control. Before the Persians, the Ionian Greeks were part of the kingdom of Lydia. The last king of Lydia was a man named Croesus. In the reading in Herodotus for this assignment, you read about how the Athenian lawgiver Solon visited the wealthy Croesus and answered the question “who is the most fortunate person?” Solon told him that it is not possible to count anyone as fortunate until you know how their life ends. Indeed, Croesus’ life ended in less than fortunate circumstances when Cyrus conquered Lydia and threatened to burn Croesus alive. One thing to note in the reading is the importance of the Oracle at Delphi to Croesus’ decision making process. Slide 4 Cyrus died in 530 BC. The Persian preferred hereditary succession, so Cyrus’ son Cambyses followed in his father’s footsteps as king of Persia. One of the most important events in the reign of Cambyses was the conquest of Egypt. Much of the second book of Herodotus’ Histories (but outside of the required reading for this assignment) is devoted to an in‐depth discussion of the customs and society of the Egyptians. One thing Herodotus likes to do is go off on ethnographic tangents when it suits him. Herodotus uses Cambyses’ conquest of Egypt as an excuse to go off on a very lengthy digression on Egypt. Darius, the son of one of Cyrus’ military officers, seized power after the death of Cambyses and became the third king of Persia. I did want to mention how the Persian provincial system worked. The Persian Empire was a conglomeration of many different peoples. The empire was divided into satrapies with each satrapy governed by an official called a satrap. Satraps had a great deal of autonomy with little oversight from the central government. In fact, many satrapies became hereditary positions kept within a particular aristocratic family. Slide 5 Like Cyrus and Cambyses, Darius sought to expand the Persian Empire. He concentrated especially on his western borders. He moved across the Hellespont into Thrace and Scythia. Aristagoras, the tyrant of Miletus, convinced the local Persian satrap Artaphernes to support his war against the island of Naxos. After the invasion had begun, the Persians withdrew their support. In retaliation, Aristagoras decided to side with the Ionians and help them with their wish to rebel against their Persian overlords. He then went around helping the cities in Ionia throw off their local tyrants to better unify them against Persia (and make them easier to control himself). Aristagoras went to Sparta to ask for military aid against Persia. Although at first willing, the Spartan king Cleomanes changed his mind when he found out how far from the sea his men would have to march. After striking out in Sparta, Aristagoras went to Athens. The Athenians were more receptive. The Athenians also felt more kinship with the Ionians because it had been Athens and Euboea who had been most responsible for colonizing Ionia in the Dark Ages. Slide 6 With Athenian backing, Aristagoras returned to Ionia and launched an expedition against the city of Sardis, the capital of the Ionian satrapy. He successfully captured the city, but was unable to dislodge the Persian defenders from the citadel of the city. What happened next is debated. The city of Sardis caught fire and burned down. Whether the Ionians set the fire deliberately is not known for certain. Darius, however, was angered at the news and vowed to take vengeance on the Athenians. The war raged on for several more years. In 494, however, the Ionians were defeated in a naval battle off the island of Lade near Miletus. As was common with the near eastern empires, Darius dealt with the rebels harshly. Many were uprooted and settled in remote parts of the Persian Empire as a warning against future rebellion. Darius believed firmly in the idea that harshness was the best form of deterrence. Indeed, when he was preparing his invasion of Greece, many cities, especially in the north of Greece, surrendered without a fight rather than face the consequences of resistance. Slide 7 In Herodotus, the burning of Sardis was a major motivation for Darius’ invasion of Greece. In truth, Greece was probably next on Darius’ list of lands to conquer anyway. His first attempt to take an invasion force to southern Greece met with disaster. The Persian commander, Mardonius, followed the normal route along the coast from the Hellespont westward past Thrace. Ancient ships were not very good in the open sea, so they were forced to stay close to land. The route was a long one, but the safest and stuck close to territory the Persians already controlled. The fleet was destroyed, however, when passing Mount Athos which is at the southern point of one of the prongs on the Chalcidice peninsula. The sea is treacherous at that point and storms frequently gave problems to ancient shipping. Two years later, Darius tried again, but this time he sent the fleet directly across the Aegean using the islands as stopping points along the way. The fleet landed at Marathon, a plain on the opposite side of the mountains from Athens. Slide 8 The Athenians quickly marched to Marathon to meet Darius’ army. They sent a runner to Sparta to ask for help, but the festival of the Carnea prevented the Spartans from leaving immediately. One of the drawbacks to a democratically‐run military made an appearance in the days leading up to the Battle of Marathon. Because each tribe contributed one strategos (or general) to the army, decisions had to be made as a committee. On this occasion, the generals were split five against five as to whether they should engage the Persians immediately or wait for the Spartans. Miltiades believed they should attack right away and persuaded the polemarch Callimachus to cast the deciding vote in favor of attack. Slide 9 The Athenians were overwhelmingly successful at the Battle of Marathon. Although the specific numbers on the two sides are debated, it is clear that the Greeks were outnumbered. They were also lacking in archers and cavalry. Much of their strategy sought to counter those disadvantages. Herodotus tells us that the Greeks advanced “at a run”. How far the Greeks ran is debatable. More than likely, it was just the last stretch as they sought to disorient the Persians (who always hoped to terrify their opponents with sheer numbers) and get out of range of the Persian archers as quickly as possible. Ancient bows could do little to harm heavy infantry, but they could still do much to erode morale. They also put more men on the flanks to prevent the more numerous Persians from outflanking them. They could also better stand an attack on the flanks from the cavalry. In the end, the lightly‐ armored Persians could do little against the heavy infantry hoplites. The Greeks were also more experienced fighters and were eager to protect their homeland while the Persian army was mostly made up of conscripts drafted from different parts of the Persian Empire. Slide 10 Their defeat of the Persians at Marathon made the Athenians one of the most important city states in Greece. Its leaders and soldiers were glorified and made national heroes. Politics in Athens also matured and became more competitive. The process of ostracism, supposedly instituted by Cleisthenes, had its first victims in the years after Marathon. Every year, the Athenians would cast a vote for the person they would most like to see removed from politics and exiled. It was a kind of reverse popularity contest. Numerous examples of ostraka with names written on them for the ostracism vote have survived. On the examples shown here, you can see the names of Aristeides, Themistocles (who was not ostracized), Kimon, and Pericles. Kimon and Pericles will be important figures in upcoming assignments.