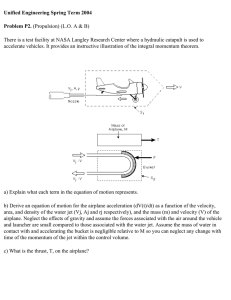

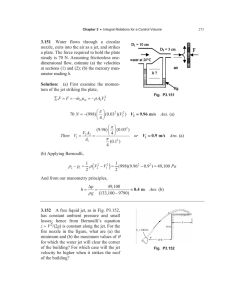

Fluid Mechanics: Finite Control Volume Analysis - Chapter 3

advertisement