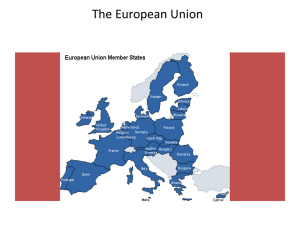

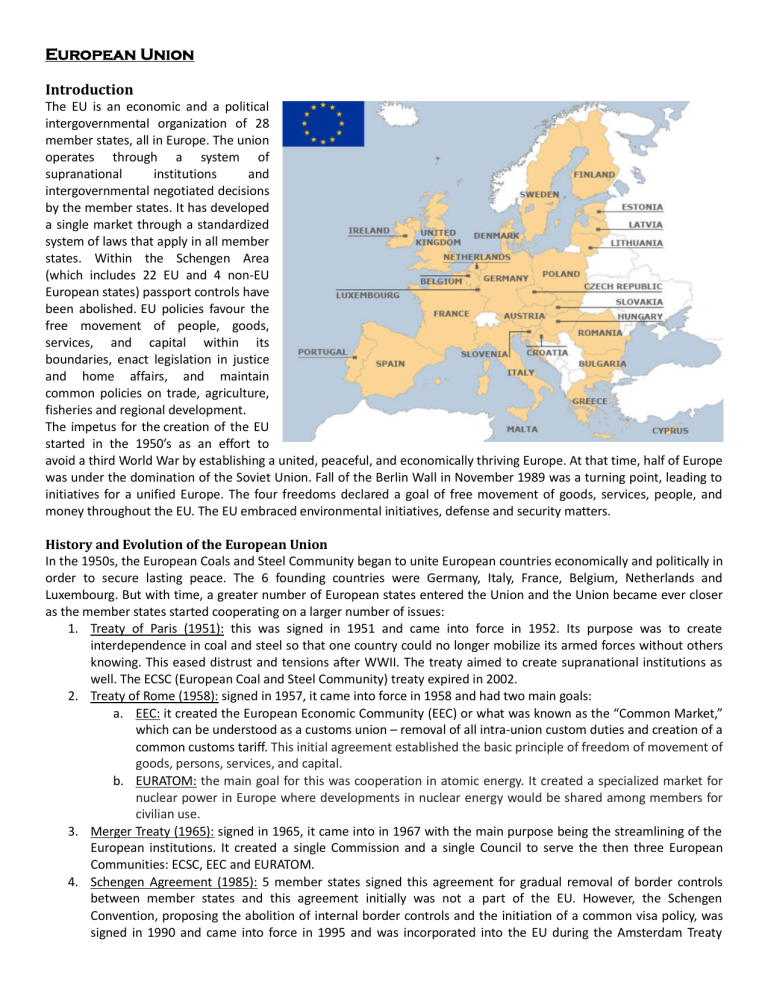

European Union Introduction The EU is an economic and a political intergovernmental organization of 28 member states, all in Europe. The union operates through a system of supranational institutions and intergovernmental negotiated decisions by the member states. It has developed a single market through a standardized system of laws that apply in all member states. Within the Schengen Area (which includes 22 EU and 4 non-EU European states) passport controls have been abolished. EU policies favour the free movement of people, goods, services, and capital within its boundaries, enact legislation in justice and home affairs, and maintain common policies on trade, agriculture, fisheries and regional development. The impetus for the creation of the EU started in the 1950’s as an effort to avoid a third World War by establishing a united, peaceful, and economically thriving Europe. At that time, half of Europe was under the domination of the Soviet Union. Fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 was a turning point, leading to initiatives for a unified Europe. The four freedoms declared a goal of free movement of goods, services, people, and money throughout the EU. The EU embraced environmental initiatives, defense and security matters. History and Evolution of the European Union In the 1950s, the European Coals and Steel Community began to unite European countries economically and politically in order to secure lasting peace. The 6 founding countries were Germany, Italy, France, Belgium, Netherlands and Luxembourg. But with time, a greater number of European states entered the Union and the Union became ever closer as the member states started cooperating on a larger number of issues: 1. Treaty of Paris (1951): this was signed in 1951 and came into force in 1952. Its purpose was to create interdependence in coal and steel so that one country could no longer mobilize its armed forces without others knowing. This eased distrust and tensions after WWII. The treaty aimed to create supranational institutions as well. The ECSC (European Coal and Steel Community) treaty expired in 2002. 2. Treaty of Rome (1958): signed in 1957, it came into force in 1958 and had two main goals: a. EEC: it created the European Economic Community (EEC) or what was known as the “Common Market,” which can be understood as a customs union – removal of all intra-union custom duties and creation of a common customs tariff. This initial agreement established the basic principle of freedom of movement of goods, persons, services, and capital. b. EURATOM: the main goal for this was cooperation in atomic energy. It created a specialized market for nuclear power in Europe where developments in nuclear energy would be shared among members for civilian use. 3. Merger Treaty (1965): signed in 1965, it came into in 1967 with the main purpose being the streamlining of the European institutions. It created a single Commission and a single Council to serve the then three European Communities: ECSC, EEC and EURATOM. 4. Schengen Agreement (1985): 5 member states signed this agreement for gradual removal of border controls between member states and this agreement initially was not a part of the EU. However, the Schengen Convention, proposing the abolition of internal border controls and the initiation of a common visa policy, was signed in 1990 and came into force in 1995 and was incorporated into the EU during the Amsterdam Treaty negotiations in 1997 to establish the Schengen Area in which were included some non-EU members (Norway, Iceland and Switzerland) and in which two EU members were not included due to their own reservations (UK and Ireland). 5. Single European Act (1987): by the time this agreement was signed, Denmark, Ireland, UK and Greece had become members of the Common Market, the role of the European Parliament had been enhanced and environment had become an important subject for the Union. This treaty however, increased cooperation among the members through various steps: a. Single Market: it set out an agenda to make Europe a Single Market by 1992 and it did so by striving for harmonization of regulations and removal of non-tariff barriers. b. European Political Cooperation: codification of the European Political Cooperation was the forerunner of what came to be known as European Union’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). c. Role of the Parliament: the European Parliament was given more powers as it could legislate on more subjects under this Act and its role in legislation was increased giving it a proper say for the first time (as compared to the Council and the Commission). 6. Maastricht Treaty (1992): this was signed in 1992 and came into force in 1993 with the main objective being the preparation for an economic union and the creation of a political union. a. European Union: the treaty established the Pillar Structure of the European Union. The first pillar was where the supranational institutions of the EU (European Parliament, the Commission and the European Court of Justice) had the most power and say while the other two were mainly intergovernmental in nature: i. First Pillar: this was one supranational pillar created from three European Communities which included the following: 1. European Coal and Steel Community 2. European Community (EEC was renamed as EC in 1993) 3. European Atomic Energy Community ii. Second Pillar: this was an intergovernmental pillar which included only the CFSP. iii. Third Pillar: this was another intergovernmental pillar which included only the Justice and Home Affairs (JHA). b. Economic and Monetary Union: so far as economic reforms are concerned, the Union decided to form an EMU through three steps: i. Liberalization of capital movement; ii. Convergence of economic policies; iii. Establishment of a European Central Bank (ECB) and a common currency, the Euro. c. The Euro Convergence Criteria: in order for the member countries to adopt the Euro as their currency, a few conditions were set by the Maastricht Treaty known as the Euro Convergence Criteria or as the Maastricht Criteria which imposed limitations and conditions on inflation rates, government deficit, gross government debt, exchange rates and interest rates. 7. Treaty of Amsterdam (1997): signed in 1997 and enforced in 1999, it amended a number of treaties signed by the member states previously including the Maastricht Treaty: a. Empowering the European Parliament: member states agreed to devolve certain powers from national governments to the European Parliament across diverse areas including legislation on immigration, adopting civil and criminal laws, and enacting a Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). b. Institutional Changes: a number of institutional changes were implemented for expansion as new member states joined the EU. c. Incorporation of the Schengen Treaties: the treaty also incorporated the Schengen treaties into the EU law – before this the Schengen treaties operated independently from the EU. d. Issues Related to CFSP: new principles and responsibilities in this field were laid down and the treaty provided for a High Representative for EU Foreign Policy, who together with the Presidents of the Council and the Commission, became a representative of EU in the outside world. e. Legislative Procedure: the co-decision procedure which later became known as the Ordinary Legislative Procedure was reformed to make the Commission more politically accountable to the Parliament and to empower the Parliament by giving it a greater role in the legislative process. f. Closer Cooperation: it provided for closer cooperation between those member states who were willing to cooperate contingent on their cooperation not being in violation of any EU law or detrimental to the interests of EU. 8. Treaty of Nice (2001): signed in 2001, it came into force in 2003 and its main aim of reforming the institutions so that EU could work effectively after its member states increased to a total of 25, was fulfilled by amending the Treaties of Rome and Maastricht and by building upon the Treaty of Amsterdam: a. Reformation of the Commission and Council: the main reforms targeted the Council by changing the method of voting from a weighted voting system to a double majority system aka qualified voting system. Methods for changing the composition of the Commission were also laid down. b. Expansion of the Parliament: number of seats in the Parliament were increased to 732 in lieu of the addition of new members. c. Closer Cooperation: rules laid down in the Treaty of Amsterdam regarding closer cooperation were viewed as impracticable and were thus changed. 9. Treaty of Lisbon (2007): signed in 2007 and enforced in 2009, this amended the two treaties which form the constitutional basis of the EU: the Treaty of Rome and the Maastricht Treaty. Both treaties were renamed as Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and Treaty on European Union respectively. Its goals was to make the EU more democratic and effective in dealing with global issues: a. European Union: it merged the three pillars structure and gave the Union a legal personality as all of its institutions and offices were combined into what came to be known as the European Union. b. Expansion of Double Majority Voting: the list of subjects that required double majority for legislation was expanded. c. More Powerful Parliament: powers of the Parliament related to legislation and budget were increased. d. President of the European Council: the office of a permanent President of the European Council was created. e. HR of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy: High Representative for Foreign Policy was done away with establishing the HR of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and the HR was made one of the Vice-Presidents of the Commission. f. Charter of Fundamental Rights: the Union’s bill of rights was made legally binding on all member states. Organizational Structure and Decision Making System EU is more than a mere confederation of states, and the organizational structure and decision making system of the EU have been evolving for more than 6 decades. There are two types of legislative processes in the EU: 1. Primary Legislation: this is the term used to refer to the Treaties under which the Union itself operates and thus provides a basis for the secondary legislation. These Treaties dictate the organizational structure, decision making processes and nature of the organization. 2. Secondary Legislation: this is the term given to regulations, directives and recommendations adopted by the EU which have a direct impact on the lives of European citizens. The Seven Decision Making Bodies Article 13 of the “Treaty on European Union” lists a total of seven principal decision making bodies of the EU: 1. European Council: based in Brussels, it is the EU’s top political institution and it provides impetus and direction to the Union. It provides broad outlines only and does not legislate at all. a. Formation and Composition of the European Council: although the heads of state and government used to meet in informal summits since 1961, the first formal summit, baptized as the European Council, was held in 1974. Its meetings – usually there are 4 annual meetings – are basically summits of the heads of state or government and the President of the European Commission. Thus it brings together national and EU level leaders. b. Presidency of the European Council: the system changed with time and can be divided into two main categories according to the eras in which each system was in force: i. Rotational (1975 – 2009): the system was rotational in nature with the head of the member state which held the Presidency in the Council of the European Union being nominated as the President of the European Council. The seat was rotated from one country to some other after every 6 months. ii. Permanent (Post 2009): the post established by the Treaty of Lisbon came to be known as Permanent President as compared to Rotational President. The permanent President is elected by a qualified majority vote of its members, for a period of two and a half years and can be reelected once and his/her job is to coordinate the European Council’s work and ensure its continuity. c. Functions of the European Council: the European Council does not pass any laws but provides a general direction to the Union. Its main functions are as follows: i. Impetus and Direction: it gives political impetus for the development of the Union and sets the general objectives and priorities for it. ii. Dealing with Sensitive Issues: issues that the Council of Ministers is unable to agree on are dealt with by the European Council. iii. Tackling International Problems: the European Council performs this role via the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) which is basically a mechanism for coordinating the foreign policies of EU’s member states. 2. European Parliament: it is the elected body that represents the EU’s citizens and forms in concert with the Council, the legislative branch of the European Union. a. Formation and Composition of the Parliament: with its first meeting being in 1952, it is one of the oldest institutions of the EU and was initially called the Common Assembly of the ECSC. Over the years it evolved and came to be known as the European Parliament. It has a total of 751 members as of July 2016. Since 1979, MEPs (Members of the European Parliament) have been elected directly on the basis of universal suffrage, every 5 years. Moreover, there a few restrictions and rules that were put in place by the Treaty of Lisbon: i. Maximum MEPs: in order to ensure that the number of seats in EP did not grow indefinitely every time a new member state joined, the total seats were capped at 751 (President + 750). ii. Maximum MEPs per Member State: no member state could have more than 96 representatives. iii. Minimum MEPs per Member State: no member state could have less than 6 respresentatives. iv. Degressive Proportionality: greater the population of a member state, greater the number of seats it has in the EP and greater the number of people that each representative of that member state represents. b. Powers and Functions of the Parliament: the European Parliament has a number of responsibilities and functions: i. Legislative Functions: together, the Council of the European Union and the Parliament form the legislature of the Union. It has monthly plenary sessions in Strasbourg but also meets in Brussels for any additional sessions. The Parliament takes part in the legislative work in two ways: 1. Ordinary Legislative Procedure: this method has with time become the dominant one and was previously known as ‘co-decision.’ Parliament shares equal responsibility with the Council in legislating in all areas that require a ‘qualified majority’ vote in the Council. Since the Lisbon Treaty, these areas constitute more than 90% of EU legislation. The Commission presents a proposal to both bodies responsible for legislation. The Parliament and the Council can reach an agreement on the proposal as soon as the first reading but if they are in disagreement after the second reading, the proposal is brought before a conciliation committee which must agree on a compromise. 2. The ‘Assent’ Procedure: the Parliament must ratify the EU’s international agreements, negotiated by the Commission, including any new treaty enlarging the EU. ii. Budgetary Power: since the Lisbon Treaty 2009, this power is shared equally between the Parliament and the Council in all areas, and the Parliament decides on the budget in the last instance. The Parliament has the power to reject a budget as a result of which the whole budget making process has to be started once again – through this the Parliament exercises considerable power over the EU’s institutions. iii. Control of the Executive: this is especially true when it comes to the Parliament’s supervision of the European Commission. Every 5 years, when the time comes to appoint a new Commission, the newly elected European Parliament can – by a simple majority vote – approve or reject the European Council’s nominee for the post of Commission President. Clearly, this vote will reflect the results of the recent EP elections. Parliament also interviews each proposed member of the Commission before voting on whether to approve the new Commission as a whole. At any time, the Parliament can dismiss the whole Commission by adopting a motion of censure which requires a two thirds majority (this power has never been exercised but it was used to threaten the Santer Commission who resigned of their own record). Other controls include: 1. The Commission must submit reports to the Parliament and answer MEPs’ questions. 2. President-in-office of the Council must submit at the start of its Presidency, its program. 3. President of the European Council must report to the Parliament after every meeting. iv. Supervision of Day to Day Management of Policies: these powers were mainly granted to the Parliament by the Maastricht Treaty. The Parliament can pose questions in oral and written form to the Commission and the Council or set up a Committee of Inquiry for some matter such as the CIA detention flights and mad cow disease. 3. Council of the European Union: also known as ‘the Council,’ or ‘the Council of Ministers,’ (the later term being outdated), this is where the member states get a chance to defend their national interests at the European level as the members of the Council are Ministers of the member states. The Council is based in Brussels. a. Formation and Composition of the Council: while the Council first appeared in the ECSC, it evolved over the years with the Treaties of Rome establishing two Councils and both of them being merged later by the Merger Treaty of 1967 into the Council of the EEC. It was renamed as the Council of the European Union in the Maastricht Treaty 1993 which gave it more powers as well. The Council is made up of Ministers from the EU’s national governments and every meeting is attended by one Minister from each member state and which Minister attends the meeting depends on the agenda topic: foreign affairs, agriculture, industry, transport etc. b. Configuration of the Council: legally speaking, the Council is a single entity but it is divided into several configurations where each council configuration deals with a different functional area, for example agriculture and fisheries. In this formation, the council is composed of ministers from each state government who are responsible for this area: the agriculture and fisheries ministers. The chair of this council is held by the member from the state holding the presidency. c. Presidency of the Council: the member states take it in turns to hold the Council Presidency where a turn expires after every 6 months. So every 6 months the presidency rotates between the states, in an order predefined by the Council's members, allowing each state to preside over the body. d. Powers and Functions of the Council: the Council was made quite powerful by the Maastricht Treaty but the Treaty of Lisbon has shifted the balance of power in favour of the European Parliament. The Council still has important powers and functions: i. Legislative Function: the Council and the Parliament together form the legislature of the EU and according to the Treaty of Lisbon, the Council has a few ways through which it can take decision: 1. Unanimously: this is for important questions such as those related to tax, entry of a new state into the EU, amending the Treaties or launching a new common policy. 2. Qualified Majority: this is the most prevalent method of passing laws. The Council decision is adopted if a specified number of votes are cast in its favour. The number of votes given to each EU member state is an approximate reflection of the size of its population in the EU. There has been a change in the qualified majority voting system from 1st November 2014 in accordance with the Lisbon Treaty: a. Pre 1st November 2014: according to this system, a decision was adopted if: i. 73.9% votes were cast in favour; ii. It was approved by a majority of member states and iii. The member states that approve the decision represented at least 62% of the EU’s population. b. Double Majority Qualified Majority Voting: according to this new post 1st November 2014 system, a decision is adopted if: i. At least 55% of the member states are in favour of it and ii. The states in favour represent at least 65% of the EU’s population. 3. Simple Majority: this simply means that majority of the votes should be in favour of a policy for it to be passed by the Council. ii. Budgetary Power: this power is shared with the Parliament as mentioned before. iii. Coordination of Policies: it ensures the coordination of broad social and economic policies. iv. CFSP guidelines: the Council sets out guidelines for the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). Legal instruments used by the Council for CFSP are different from the legislative acts. These instruments include: 1. Common Positions: includes defining the European foreign policy towards a particular third country or a region or an issue. A common position once agreed is binding on all EU member states which must follow and defend the policy which is regularly revised. 2. Joint Actions: a coordinated action of the member states to deploy resources in order to achieve an objective. 3. Common Strategies: these define an objective and commit the EU’s resources to the achievement of that objective for 4 years. v. International Agreements: this body is the one which concludes/signs international agreements on behalf of the EU once they have been negotiated by the Commission. 4. European Commission: the Commission is a key EU institution as it forms the executive branch of the EU. It works like a cabinet government and its members, appointed by the national governments, are called Commissioners. The Commission is based in Brussels. a. Formation and Composition of the Commission: its members are appointed for a 5-year term by agreement between the member states, subject to approval by the European Parliament. There is one Commission member called ‘Commissioner’ from each EU country, including the Commission President and the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (HR), who is one of the Commission’s vice-presidents. A new commission is appointed every 5 years, within 6 months after the elections to the EP. The procedure of appointing a new commission is as follows: i. Appointing a President: the European Council proposes a new Commission President who must be elected by the EP. Same procedure applies for the appointment of the HR. ii. Appointing the Commissioners: all member states except those who provided the President and the HR nominate their own Commissioners. iii. The Parliamentary Go-Ahead: the new EP interviews all proposed members of the Commission and if approved, the new Commission starts its work from the upcoming January. b. Presidency of the Commission: the President must be nominated by the European Council and elected by the EP. The President is assisted by a number of Vice Presidents among whom is also the HR who is one of the VPs. c. Powers and Functions of the Commission: i. Propose Legislation: it formulates and submits proposals for new legislation to the Parliament and the Council i.e. the legislature. ii. Implementation of EU Policies: the policies formulated by the legislature are executed (managed and implemented) by the Commission. iii. Budget Administration: the budget approved by the legislature has to be administered by the Commission. iv. Guardian of the Treaties: it has to ensure together with the Court of Justice that EU law is applied properly in every member state. If any member state is found in violation, the Commission takes appropriate steps through a legal process called the Infringement Procedure. v. International Representative of the EU: before international agreements can be concluded by the Council, it is the Commission’s duty to negotiate them in order to secure better terms. In matters related to foreign affairs and security, the High Representative works with the Council but for all other issues, it is the Commission that is responsible. For example, the Commission is the EU’s spokesperson at the WTO. 5. Court of Justice of the European Union: this body forms the judiciary and its role is to ensure that all member states interpret and apply all EU laws in the same way. It is based in Luxembourg. a. Formation and Composition of the Court: to handle the case load, the Court is divided into two bodies and a tribunal: i. Court of Justice: it is composed of 28 judges, one coming from each member state and these judges are assisted by 8 Advocates General. Each member is appointed for a period of 6 years and the judges select a President whose term is of 3 years. This body deals with requests for preliminary rulings from national courts and with certain actions for annulments and appeals. ii. General Court: it is also composed of 28 judges, one from each member state. Judges serve for a period of 6 years and they elect a President for a term of 3 years. The General Court rules on all actions for annulment brought by private individuals and companies and some such actions brought by member states. iii. Civil Service Tribunal: this is a special tribunal made to resolve disputes between the EU and its civil servants. b. Powers and Functions of the Court: the Court has the following main functions: i. Application and Interpretation of Law: the Court of Justice ensures that the European law is uniformly applied and interpreted. ii. Deciding Legal Disputes: it is also responsible for settling or deciding any legal disputes that arise between member states, the institutions of the EU, businesses and individuals. c. Types of Cases Handled by the Court: the bodies of the Court handle 4 main kinds of cases: i. Preliminary Rulings: when a national court of any member state is in doubt regarding the interpretation of EU law, it asks for advice from the EU’s Court which gives a binding ‘preliminary ruling.’ ii. Infringement Proceedings: the Commission or any member state can initiate such cases if they believe that a certain member state is violating EU law. The Court then starts its own investigation and sets the matter right if need be. iii. Proceedings for Annulment: if the Commission or the Council or any member state find any law to be illegal or if any individual finds any law to affect him/her adversely, they may ask the Court to annul it. iv. Proceedings for Failure to Act: every institution of the EU is required to take certain actions under certain circumstances but if they fail to do so, the member states or other EU institutions or in some situations, an individual or a company may lodge a complaint with the Court. 6. European Central Bank: as evident from its name, this body is the central bank. It is based in Frankfurt and works independently and takes decisions without seeking or taking any instructions from other EU institutions. a. Formation of the ECB: the ECB was set up in 1998 when the Euro was introduced. The ECB is an institution of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU, an outcome of the Maastricht Treaty) of which all EU members states are a part. b. European System of Central Banks: this system is formed by the ECB along with the national central banks in Europe. c. Monetary Policy: the ECB determines the monetary policy and hence controls the money supply in the Eurozone, with price stability as the main aim. 7. Court of Auditors: this body is the financial auditor and it is based in Luxembourg. a. Formation and Constitution: the European Court of Auditors (ECA) was formed in 1977 and it operates as a collegiate body of 28 members, one from each of the member states. b. Functions and Powers: it has one main goal which is to ensure the proper utilization and implementation of the budget approved by the legislature. In other words, the ECA ensures that the EU income and expenditure is legal and regular and that the financial management is sound. Other Institutions of the EU 1. The European Economic and Social Committee: the EESC consists of 353 members from all of the EU member states who represent the organized civil society and serve in an advisory capacity. The EESC acts as a bridge between the EU institutions and the EU citizens, thus promoting a more democratic and participatory society in the EU. 2. The Committee of the Regions: the CoR is the voice of the local governments as it consists of 353 members from all over the EU who represent Europe’s cities and regions. This is also an advisory body, consulted when the issues under discussion pertain to the local governments, such as education, transportation etc. 3. The European Ombudsman: complaints about maladministration of the EU institutions are lodged by the EU citizens, residents, businessmen and institutions with the European Ombudsman who then investigates the matter. Examples of maladministration include unfairness, discrimination, abuse of power, lack or refusal of information, unnecessary delay, incorrect procedures etc. 4. The European Data Protection Supervisor: EU institutions often need citizens’ data for various purposes and the role of EDPS is to protect the privacy of the data processed by these institutions. Decision Making Process Who Makes the Decisions? The seven EU institutions are responsible for making most of the decision but when we speak of the legislative process and decisions related to policy making, there are in fact 4 bodies which have a central role: 1. The European Parliament 2. The European Council 3. The Council of the European Union 4. The European Commission What Types of Decisions are there? There are several types of legal acts which are applied in different ways: 1. Regulation: a law that is applicable and binding in all member states without any member state having to pass it separately. In fact, national laws may have to be changed if they conflict with any regulation. 2. Directive: a binding law that directs the member states to achieve some particular goal(s) with each member state deciding on the way to achieve those goal(s) on its own. 3. Decision: it is binding in its entirety and can be addressed to member states, groups of people or individuals. A ruling on proposed merger between companies will be a decision for example. 4. Recommendation/Opinion: it is not binding. The Ordinary Legislative Procedure The procedure through which some legislation is adopted is called the Ordinary Legislative Procedure which works as follows: 1. The Commission’s Proposal: on some input and recommendation from the EU citizens or from any of the EU’s bodies or on its own initiative, the Commission drafts and submits its proposal to the Parliament. 2. 1st Reading of the Parliament: the proposal is read in the Parliament which may amend the proposal and then passes it on to the Council. 3. 1st Reading of the Council: the proposal as passed on from the Parliament is read in the Council which may agree with the proposal in which it is adopted or it may disagree and amend the proposal in which case it is handed back to the Parliament for further review. 4. 2nd Reading of the Parliament: the amended proposal is read in the Parliament which may approve of it and adopt the legislative proposal (most of the proposals are adopted at this stage) or it may amend it further and hand it over to the Council for a second review. 5. 2nd Reading of the Council: if the Council agrees with the proposal handed over to it by the Parliament, the proposal is adopted but if it disagrees, then a conciliation committee is formed to resolve the matter. 6. Conciliation Committee: the conciliation committee comprises of an equal number of MEPs and Council representatives. If the committee is unable to agree on a joint text, the procedure comes to an end but if it agrees on a joint text, it is passed on to the Parliament and the Council for third readings. 7. 3rd Reading of the Parliament and Council: for the proposal to be adopted, it is essential that both approve of the text that the Conciliation Committee handed over to them. The disapproval of even a single body will result in the non-adoption of the proposal and the legislative procedure will come to an end. The Euro Crisis Formation of the EMU and Adoption of the Euro In 1992, the Maastricht Treaty was signed by EU’s member states and it came into force in 1993. Under this treaty was established the Economic and Monetary Union through three steps: 1. Liberalization of capital movement; 2. Convergence of economic policies; 3. Establishment of ECB and a single currency (the Euro). The third step was completed in 1999 when the Euro was adopted as the single currency of the EU although a few countries decided to stay out of the monetary union, and 19 out of a total of 28 members eventually joined the monetary union and adopted the Euro – these 19 members formed their own club within the EU known as the Euro Area or the Euro Zone. However, before a country could adopt the Euro as its currency, there were a few conditions it had to meet known as the Maastricht Criteria or the Euro Convergence Criteria. The conditions were embodied in the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) which was basically a tool to safeguard fiscal discipline within the EMU. The criteria are based on Article 121 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU – originating as the EEC Treaty or the Treaty Establishing the European Economic Community as a part of the Treaties of Rome, and was later renamed to TEC or Treaty establishing the European Community in the Maastricht Treaty, and finally renamed to TFEU in the Lisbon Treaty). However, the 3 basic clauses of SGP state the following: 1. A country’s budget deficit must not be more than 3% of its GDP; 2. A country’s debt must not be more than 60% of its GDP; 3. There will be no bailout i.e. if a country is unable to meet its debt obligations, it must default. The fact of the matter was that there was no economic basis for any of these 3 conditions laid out in the SGP and they did not even take into account, the economic cycle. They were agreed upon only because the strongest member states fulfilled all of these conditions at the time the pact was drawn. Furthermore, countries that did not satisfy all of these conditions were allowed to enter into the monetary union and adopt the Euro. Pre-Crisis Risk Factors Alarm bells had been going off for quite a long time but all signs of an economic crisis had been ignored by the EU which reveled in its temporary economic growth along with its political unity and strength: 1. Fiscal and Monetary Policy Divorce: since the establishment of the ECB, all countries within the Euro Zone gave up their own currencies and adopted the Euro, gave up their right to form their own monetary policies which are formed by the ECB while the national governments form their own fiscal policies, and gave up their own central banks with ECB as the only central bank. The monetary-fiscal policy divorce has been dubbed by many economists as a recipe for disaster. 2. Divergence of Competitiveness in the Euro Zone: some countries were more competitive than others due to differences in the cost of labour. It is not surprising that the PIIGS countries had the highest costs of labour, making their exports less competitive and thus exposing them to trade deficits. These countries had a few options all of them being impracticable: a. Lowering Wages: not feasible due to ‘downward wage rigidity.’ b. Increasing Productivity: this is easier said than done and is a long term process. c. Devaluing Currency: this helps to export more but was not possible due to ECB. 3. Debt Levels: the PIIGS countries also had higher debt levels before the crisis hit and Greece, Italy and Portugal were already suffering from debt trap before 2008. This was due to a number of reasons: a. Government Over-Spending (Deficit Spending): the governments in some countries spent on unnecessary things like in Greece and Italy where corruption was rampant, tax collection was low and expenditure on pensions, wages and social welfare benefits was high. b. Availability of Loans: since these countries were now a part of the Euro Zone and they had adopted a stronger currency which had the backing of Germany, international creditors were more willing to lend them money. 4. Overlevered Banks: by 2007, some banks had given more credit than what the countries they operated in could produce in terms of output. In Ireland’s case for example, loans from domestic banks and other credit institutions to the private sector (especially the housing market, same as in Spain) were 184% of its GDP. This meant that if banks were hit by a financial crisis, huge international loans would be needed to stabilize the banking sector and the economy. 5. Financial Interdependence: establishment of the Euro Zone meant that banks in one country within the Zone could lend money to institutions and businesses in another country. While this facilitated business, commerce and trade, it also exposed the 19 Euro Zone members to greater financial risks vis-a-vis contagion. EU and the Global Financial Crisis 2008 When the world was faced by what came to be known as the credit crunch, European banks in general and Euro Zone member states were faced by a huge crisis. This happened because the European banks like many other banks all around the globe were exposed to a lot of US asset and mortgage backed securities which were worth nothing after the US housing market collapsed. This had significant repercussions for the European economies: 1. Credit no Longer Available: every bank and all investors wanted to secure their own assets which meant that they were unwilling to trade with each other within countries and internationally. Cheap credit which had been available for some years was no longer available and countries that had been dependent on international credit had no idea what to do. 2. Banks Demanding Debtors to Pay-up: banks who had loaned money to countries and institutions previously were demanding them to pay their loans back but many countries and institutions were unable to do so due to the aforementioned pre-crisis risk factors and because whatever money the governments had, they started investing in domestic banks (they had given a lot of credit to the private sector which was no longer operational and could therefore no longer pay back what it had borrowed). 3. Loss of Trust in the Euro: lenders had always thought that the Euro Zone was strong economically and they had always thought that in case one country failed to pay its debts, some other country would pick up the tab since they were all interconnected and interdependent and the loss of trust in Euro would harm them all. But now, since every country faced a crisis of its own, they were less willing to pay back what others had borrowed – internal stabilization was the priority. Eventually Germany came to the rescue but its money was tied to strict austerity measures. However, loss of trust in the Euro resulted in higher interest rates to reflect the higher risk and it was partially this speculation that resulted in a sale of assets in Europe with no one willing to buy those assets again. Liquidity Crisis The higher interest rates could have been dealt with if each country had control of its own monetary policy. Due to the high interest risk reflected by increasing yields on bonds, people were less willing to buy them from the government and more willing to sell them off at whatever price they could to cut their losses. 1. Independent Country: if UK were hit by a shock, investors would sell off its bonds for pounds which they will want to dump, causing the pound to devalue. But the Bank of England would willingly buy them and re-inject them into its economy. Thus liquidity will remain bottled up in the UK economy. 2. Country in the Monetary Union: when Spain got hit by the real estate shock (its own construction and housing market collapsed), investors started selling Spanish bonds in return for Euros. These Euros will be sold not to the Spanish Central Bank (since there is no such thing – replaced by the ECB) but in exchange for stable assets such as German bonds. Liquidity will leave Spain and this will cause bond yields to rise further. In this case, the ECB played a positive role by buying up short-term peripheral debts (bills – not bonds which are long term – issued by Spain and Italy) through an expansion of its balance sheet. Basically it means that the ECB will buy those bills by creating new money in order to help those countries counter the negative effects of speculations that investing in their bills and bonds is very risky. The Case Study of Greece Greece was and still is the most vulnerable and the worst affected country by the Euro crisis due to a number of reasons: 1. Pre-Euro Era Debt: Greece was unable to take full advantage of the Marshall Plan and could not capitalize on it like other European countries did. It had a failed start and even during the 1970s, it was mostly dependent on issuing bonds for its deficit spending. 2. Pre-Crisis Risk Factors: almost all of them applied to Greece including lack of competitiveness and high debt levels especially since Greece had access to cheap credit after it joined the Euro Zone – before that, Greece could borrow only on high interest rates. 3. Fraud: the country used financial wizardry in order to hide the true extent of its debt even before the crisis began. In 2009, credit rating agencies reviewed Greece’s economy and it turned out that while the Greek government had been showing its deficit to GDP ratio as a mere 6% (above the 3% mark as set in the SGP) it had actually been 12.7% and their credit rating was revised to CCC (the worst) which led to an indefinite increase in bond yields. This liquidity crisis faced by Greece turned into an issue of solvency. 4. Troika’s Imperialism: the Troika has also been blamed for Greek’s economic woes as they have imposed strict austerity measures as a result of which it seems that the Troika have capitalized at the expense of Greek people – the money loaned to Greece has not gone into the Greek economy but has been used to pay off prior debts and in the process new debt has been accumulated. Public assets have been sold off, unemployment is on the rise and Greece is worse off than it was when the crisis started. It seems that the Troika has used the Greece government to take away wealth from its people on behalf of the Troika in order to pay the Troika and the private banks and lenders. This new form of imperialism can be summarized as follows: “It starts as a free trade zone or 'customs' union. A single currency is then added, or comes to dominate, within the free trade customs union. A currency union eventually leads to the need for a single banking union within the region. Central bank monetary policy ends up determined by the dominant economy and state. The smaller economy loses control of its currency, banking, and monetary policies. Banking union leads, of necessity, to a form of fiscal union. Smaller member states now lose control not only of their currency and banking systems, but eventually tax and spending as well. They then become 'economic protectorates' of the dominant economy and State-such as Greece has now become.” Response to the Greek Debt Crisis: The Troika and Austerity Risking on a default, Greece entered into an agreement with the Troika (European Commission + ECB + IMF) who gave Greece three bailout packages over the years (in 2010, 2012 and 2015), all conditioned on austerity measures. After the third bailout package, Greece’s debt stands at a staggering € 323 billion which measures up to 180% of Greece’s GDP (as compared to 60% as set in the SGP). Austerity measures included higher taxes, less government spending, privatization of industries and assets etc. But this resulted in political turmoil including confrontations between the public and the police in which lives were lost too. Austerity measures while useful in the short run cannot solve problems in the long run especially as they have many negative consequences: 1. Keynesian Economics: in a recession, there is a decrease in demand as the private sector consumption falls. For economic growth to continue, the aggregate demand needs to be stabilized which can be done only through government spending. 2. Unemployment: in Greece, unemployment rose to 26% and for the youth, it is still above 50%. 3. Austerity is Self-Defeating: when governments spend less during a recession, the GDP shrinks and this leads to lesser taxes and thus lesser revenue. Possible Solutions Many solutions have been proposed and many are possible though none of them is free from political hurdles: 1. European Fiscal Union: this will allow a single fiscal policy to complement the single monetary policy that is made by the ECB. Many have suggested that this is what is needed for a long term permanent solution to the problems that are inherent in the structure of the EMU. Essentially, this will bring to an end the divorce that exists between the monetary and fiscal policies in the Euro Area. 2. Eurobonds: this can be another long term solution although for this to be effective the first suggestion has to be implemented first. The issuing of Eurobonds instead of issuing of bonds by each country separately means that the debt that is being faced by the peripheral countries will be taken up by the Euro Area as a whole. The solvency crisis which is being faced by smaller economies will no longer be an issue if it has to be faced by the much larger Euro Area. However, this will be a moral wrong and will definitely set a wrong precedent. 3. Grexit from the Euro Zone only: Greece could exit from the Euro Area and go back to its Drachma which will allow devaluation in order to make Greece’s goods competitive. It will be able to negotiate a partial restructuring of its economy with a partial default on its loans but no massive defaults as such a policy would be detrimental to the international banking system – many foreign banks including those in the US hold Greek debt. 4. Protectionism: the EU should allow weaker economies to follow certain protectionist policies for a few years in order to stabilize and strengthen targeted sectors within their economies. Once this goal has been achieved, these countries can return to liberal policies. Brexit Background: Britain’s Rocky Relations with the EU Britain’s uneasy relationship with the European Union has a long history. In 1950 only 10% of Britain’s exports went to the six countries that formed the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). Concerns about the Commonwealth, the welfare state and sovereignty led it to miss the boat at the Messina conference in 1955, when the ECSC countries decided to form the European Economic Community, the precursor of today’s EU. Instead, in 1960 Britain cajoled six much smaller European countries into forming the European Free-Trade Association (EFTA). But in 1961 a Tory government under Harold Macmillan, impressed by the EEC’s superior economic performance, decided to submit the first of several British applications to join. Britain eventually joined in 1973 under Edward Heath. Since then, Britain always voiced its criticisms about the monetary union and in all the treaties signed on the issue, it managed to get an opt-out clause especially when it came to the establishment of the Eurozone, which Britain never joined. Causes: The For/Against Debate The debate on “Brexit vs. Bremain” was focused on a number of areas including trade (with EU and with other countries), EU budget (Britain’s contribution to it), regulation (free trade versus greater legislative sovereignty), immigration (EU and non-EU migrants) and influence (Britain’s influence within EU and how EU augments Britain’s power). The chart below explains the points in detail. Cameron’s Negotiations with the EU Basically Cameron wanted four things and what was negotiated as a result on each one of them was as follows: 1. Emergency Brake: Britain can keep in place special rules for 7 years for EU workers working in Britain. 2. Child Benefits: while UK wanted to stop all child benefit payments to children outside UK whose parents worked in UK, the deal negotiated allowed child benefit payments to be indexed to the cost of living for children living outside the UK. 3. Stronger Protection for Non-Euro vs. Eurozone: UK wanted to protect countries outside the Eurozone from regulations made by those inside and it was able to get a decision where it would be allowed to start debate amongst Eurozone countries about problems of the zone – a delaying tactic instead of a complete prevention. 4. Ever Closer Union: UK wanted stronger guarantees that UK will not be made a part of ever closer political union of Europe and it got the guarantee it was looking for. The Referendum It took place on the 23rd of June in 2016 and 52% of the voters voted for Brexit while 48% voted against it. The Brexit vote showed variations according to certain demographic factors: the younger were more inclined to vote for remain, the more educated were also more inclined to vote for remain, those who earned more were also more likely to vote for remain and those who had been born outside of the UK were also more inclined to vote for remain. However, the results were unexpected and PM David Cameron resigned after the referendum even though it was a legally non-binding referendum which had a status of only an opinion poll in which most of the younger people did not show up at the polling stations. Timeline of the Exit According to British PM Theresa May ("We are going to be a fully independent, sovereign country – a country that is no longer part of a political union with supranational institutions that can override national parliaments and courts.”), UK will have invoked Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union (Lisbon Treaty) by March 2017 which means that Britain will leave EU by the summer of 2019 although the exact timeline may vary given that Article 50 was incorporated into EU law only in 2009 and has never been used before. However, the exact steps are as follows: 1. Invoking Article 50: first UK will inform EU that it has decided to leave the EU and for this purpose Article 50 has to be invoked, starting the 2 year timeline for negotiations between the two entities. During this time period, Britain will not be able to take part in discussions related to EU’s internal issues including its own exit unless it is in the form of negotiations between UK and the rest of the member states. For these 2 years however, UK will remain a part of the EU. 2. 2 Years of Negotiations between UK and EU: once the negotiations start and some draft deal has been reached, it has to be passed by the Council (qualified majority) and then by the Parliament for the draft to be finalized. 3. Possible Extension of Negotiations: if all the other 27 members of the EU agree, then the time period for negotiations will be extended beyond two years but if they do not see any need for extension, the EU treaties will cease to apply to UK. 4. UK Leaves EU: UK ceases to be a part of the EU and its government will enact a Great Repeal Bill which will incorporate EU law into the UK law but it will be up to the government to decide what to retain, discard or change. The Options for a UK-EU Deal There are a total of 5 types of arrangements that the UK can have with the Union and what the future holds for the two depends largely on the type of deal that the two are able to agree on during the negotiations that follow the triggering of Article 50. The following models reveal what is called the “Brexit Paradox,” what is most damaging politically is most beneficial economically and vice versa: 1. Norwegian Style EEA Agreement: UK will join the European Economic Area and maintain full access to the single market, but will have to adopt EU standards and regulations with little influence over these. The UK will make a substantial contribution to the EU budget and will be unable to impose immigration restrictions. This will not address Britain’s political problems with the EU and will bind it into agreements in the formulation of which it will have little to no say. 2. Turkish Style Customs Union: internal tariff barriers will be avoided, with the UK adopting many EU product market regulations, but sector coverage of the customs union will be incomplete. The UK will be required to implement EU external tariffs, without influence or guaranteed access to third markets. This will essentially be a bad compromise for UK. 3. FTA Based Approach: UK will be free to agree FTAs independently and its relationship with the EU will itself be governed by some FTA. However, as with all FTAs, UK will have to agree to common standards and regulations. 4. Swiss Style Bilateral Accords: the UK and the EU will agree on a set of bilateral accords which govern UK’s access to the single market in specific sectors. Concern in Brussels about cherry picking may limit the sectors. UK will become a follower of regulation in the sectors covered, but will negotiate FTAs separately. This may be possible but may not be liked by EU as much as the FTA approach will be. 5. MFN Based Approach: there will be no need to agree to common standards and regulation, but at the expense of facing the EU’s common external tariff, which will damage UK’s trade with the EU in goods as well as services. Non-tariff barriers will be likely to emerge over time to damage trade in services in particular. This does not sit well with Britain’s and EU’s liberal trade agenda. One may say that the FTA based approach and the Swiss Model are most likely to be followed with the former being favourable to both parties depending on the exact nature of the deal that is signed. In the best case scenario, Britain will be able to get a deal tailor made for its case and in the worst case scenario, there is no deal at all and the two will have to settle, after long protracted negotiations, for simple WTO rules. Impacts of Brexit The uncertainty that looms over the fate of Britain’s position in the EU is not likely to have any positive effects on any of the stakeholders. A prolonged uncertainty may fade out eventually but in the short run, it can lead to disaster. In the long run however, Brexit can have many adverse political and economic effects: 1. Political: there will be widespread repercussions of Brexit for UK, for EU and for the world: a. End to Dual Representation of Britain: as a part of the EU, Britain has a dual representation on the international stage since most forums have one seat for each of the member states of EU and one seat for the EU. So most of Britain’s interests are represented twice in the international forums. But this will come to an end once Brexit comes to pass. b. Britain could have done more from within EU: whatever Britain’s fight with EU was and is, it could have negotiated a better deal for itself and could have even led reforms within EU if it had chosen to remain a part of EU. Now, even if Britain delays the triggering of Article 50 indefinitely, the hostile environment will make it impossible for such fruitful negotiations to take place successfully. c. Possible Disintegration of UK: there are various reasons for such a scenario: i. Scotland’s separatist movement will gain ground and ask for the same right that UK practiced. ii. British politics will show a greater tilt to conservatism and right wing parties will get stronger. This will lead to a greater political divide within Britain. After Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson’s shift to defending the pro-EU column however, this seems less likely to happen. d. Possible Disintegration of EU: there is a theory built on historical evidence that whenever the second most strong country leaves a union of countries, that union crumbles since the weaker countries no longer have any country that can act as a buffer between them and the dominant country – the dominant country pressurizes them more since it is in a position to. e. Rise in Separatism and Xenophobia World Over: such movements are likely to become more intense globally and such trends in politics across continents are likely to follow suit. White supremacism, Trump’s anti-migrant, xenophobic and Islamophobic rhetoric are a few examples. f. Security: issues related to security are likely to increase vis-a-vis the migrant crisis and lesser cooperation on such sensitive issues after Brexit. 2. Economic: these impacts will mostly be focused on UK and EU although some predict a global crisis like the one that occurred in 2008 to originate from Europe and many think that Brexit will accelerate the onset of such a crisis. The exact consequences cannot be predicted since they will depend largely on the exact deal that is signed between the two in case Article 50 is triggered. Until then, everything is based on apeculation: a. Economic Consequences for UK: these can be divided as follows: i. GDP: the worst and best case scenarios present a GDP growth ranging from -2.2% to +1.55% with a politically realistic range being within -0.8% to +0.6%. ii. Pound Devaluation: this has already been witnessed and GBP slid down to a 3 decade low after Brexit referendum. iii. Loss of an Export Market: UK has been exporting almost 51% of its goods to the EU and it could lose that market for its goods. Similarly, the EU exports almost 6.6% of its goods to UK and UK may have to import these goods from elsewhere. iv. Continued Contribution to EU Budget: just to maintain its standing and relations within and with the EU respectively, UK may, according to some analysts, continue to pay billions of pounds to the EU budget. v. Renegotiations on Economic Deals: deals that Britain enjoys within EU and without due to it being a part of EU will have to be renegotiated albeit from a weaker position since it will be politically weaker outside of EU. vi. Tough Choices: outside EU, Britain will have to face what is called an “avoid-avoid” conflict: 1. Opening up to low cost economies like China and India. 2. Adopting liberal migration policies to be competitive – cheap labour. b. Economic Consequences for EU: this is largely unchartered territory but one can predict that consequences for EU will be less significant than they will be for UK. Most of the impacts that Brexit could have on the EU will be political in nature, though economic impacts cannot be ignored since they both have a relationship that can best be described as one of mutual dependence. Final Analysis It is difficult to say how a post-Brexit Britain will perform politically and economically in the long run but for the time being, the economic outlook has not been as horrible as expected and predicted. Employment in the UK has been on the rise, housing prices fell initially but took off within a few weeks of the Brexit referendum, inflation has edged up but remains low, and so on. But the fact of the matter is that if a post-Brexit Britain wants to enjoy access to the European Market it will need to comply with most of the rules and regulations that accompany the benefits of access to the European Market. Moreover, the options that Britain has when it comes to signing a deal with the EU, are either unappealing or unattainable or both. The EU will not disappear as an institution or a big market. A post-Brexit Britain will have to form a set of trading and institutional relationships with it. The uncertainty is over what these would be—and how long they might take to negotiate. Whatever the case may be, uncertainty still looms over the future of Britain and EU itself and the sooner it is dealt with, the better it will be for everyone. Other Questions Pertaining to the European Union Role of Intergovernmentalism in EU Intergovernmentalism represents a way for limiting the conferral of powers upon supranational institutions, halting the emergence of common policies. Intergovernmentalism treats states, and national governments in particular, as the primary actors in the integration process. Intergovernmentalist approaches claim to be able to explain both periods of radical change in the European Union (because of converging governmental preferences) and periods of inertia (due to diverging national interests). Intergovernmentalism is distinguishable from realism and neorealism because of its recognition of both the significance of institutionalization in international politics and the impact of domestic politics upon governmental preferences. Main Purpose of EU: Politics or Economics? The Argument for Economics over Politics The European Union's primary purpose was meant to be more economic than political. Its scheme of law and regulation is meant to create, in some ways, a cohesive economic entity of its countries, so that goods can flow freely across the borders of its member nations, without tariffs, with the ease of one currency, and the creation of one enlarged labor pool, which should at least theoretically create a more efficient distribution and use of labor. There is a pooling of financial resources, so that member nations can be "bailed out" or lent money for investment, and at least theoretically, member nations are more likely to cooperate than compete. There are political implications to this union, of course. For example, member nations are expected to conform with the Union's expectations in areas such as human rights and the environment, and the Union can exact a heavy political cost on its members as a condition of giving aid, as it did in Greece, insisting on severe cutbacks and an austerity budget, which had tremendous political costs for Greek leadership. There can be political fallout even for countries that are not part of the European Union. Ukraine, for instance, which is divided on whether or not to seek admission to the union, is presently engaged in almost a civil war between those in the west who want to be part of the Union and those in the east who would prefer to align themselves with Russian interests. This is a great experiment, really, in cooperation amongst nations, who wish to be economically unified, ceding as little political and national power as possible, and it will be interesting to see how this unfolds. Will the European Union come to resemble the United States, or will it devolve into its previous collection of separate economic entities? The Argument for Politics over Economics While some argue that the primary purpose of the European Union was economic, rather than political, such a conclusion can really only be reached by ignoring the entirety of post-World War II European history. While the structures and arrangements that comprise the European Union are largely economic, the purpose of European integration is entirely political. Weary of centuries of highly-destructive uninterrupted warfare culminating in the most destructive conflict in human history, and seeking to replace the old "balance-of-power" model that had failed spectacularly twice in the same century, the leaders of West Germany, France, the Netherlands, and other West European nations sought to eliminate the political divisions that repeatedly resulted in these conflicts by integrating both politically and economically. By agreeing to common political and economic principles, the previous structure of independent nation-states would give way to a unified decision-making structure combined with economic integration that would allow each member state to specialize in areas on which it was best suited to focus. The catch, of course, was that each member state had to be prepared to sacrifice certain economic practices, such as in the area of agriculture, for the greater good. Agricultural sectors, especially in France, however, remained so politically powerful that they were able to impede the process of integration for many years. As noted, much of the discussion and activity involving the European Union focuses on economic issues. The current conflict regarding Greece's impending bankruptcy, for instance, illuminates the extent to which economic issues dominate the E.U. The European Union, however, was established primarily for political, not economic reasons.