Inquilab Bhagat Singh on Religion Revolution (S. Irfan Habib)

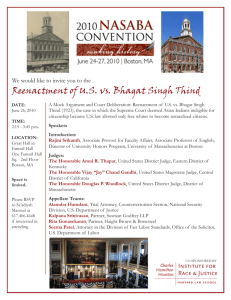

advertisement