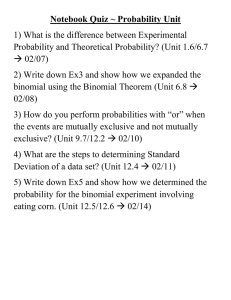

Part 2 Probability Distributions Print version of lectures in ST230 Probability and Statistics for Science by c David Soave from Department of Mathematics at Wilfrid Laurier University Includes material adapted from: Johnson, R.A. Miller & Freunds Probability and Statistics for Engineers. Pearson; 9th edition. 2.1 Contents 1 Random Variables 1 2 The Binomial Distribution 4 3 Binomial Probabilities 5 4 The Hypergeometric Distribution 11 5 The Mean and Variance of a Probability Distribution 14 6 The Poisson Distribution 20 7 The Geometric and Negative Binomial Distribution 24 1 2.2 Random Variables In most statistical problems we are concerned with one number or a few numbers that are associated with the outcomes of experiments. • Lotto Max ticket: how many of our numbers match the winning draw? • This ‘count’ is associated with a situation involving an element of chance - i.e., a random variable. Random Variable A random variable is any function that assigns a numerical value to each possible outcome. Random variables are denoted by capital letters X, Y , and so on, to distinguish them from their possible values given in lowercase x, y. 1 2.3 ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 2 Example 2.1 , Coin Tossing Consider an experiment of tossing 3 fair coins and counting the number of heads. Certainly, the same model suits the number of females in a family with 3 children, the number of 1’s in a random binary code consisting of 3 characters, etc. Let X be the number of heads (females, 1’s). Prior to an experiment, its value is not known. All we can say is that X has to be an integer between 0 and 3. Since assuming each value is an event, we can compute probabilities, 2.4 Probability Distribution The probability distribution of a discrete random variable X is a list of the possible values of X together with their probabilities f (x) = P [X = x] The probability distribution always satisfies the conditions X f (x) ≥ 0 and f (x) = 1 all x 2.5 ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 3 Example 2.2 Check whether the following can serve as probability distributions: x−2 (a) f (x) = , for x = 1, 2, 3, 4 2 x2 (b) h(x) = , for x = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 25 2.6 Cumulative Distribution Function The cumulative distribution function F (x) gives the probability that the value of a random variable X is less than or equal to x. Specifically, F (x) = P [X ≤ x] for all − ∞ < x < ∞ • From the conditions on f (x), we can conclude that the cdf F (x) is a non-decreasing function of x, always between 0 and 1. • Between any two subsequent values of X, F (x) is constant. It jumps by f (x) at each possible value x of X (see Fig. below). 2.7 ST230 (Part 2) 2 c David Soave, 2023 Page 4 The Binomial Distribution The simplest random variable takes just two possible values. Call them 0 and 1. • e.g. Good or defective components, parts that pass or fail tests, transmitted or lost signals, working or malfunctioning hardware, benign or malicious attachments, sites that contain or do not contain a keyword . Bernoulli Variable (Trial) A random variable with two possible values, 0 and 1, is called a Bernoulli variable, its distribution is a Bernoulli distribution, and any experiment with a binary outcome is called a Bernoulli trial. 2.8 The Binomial Setting We may be interested in assigning a probability model/distribution for a count of successful outcomes (a discrete variable) from a series of Bernoulli trials. • e.g. A new treatment for pancreatic cancer is tried on 250 patients. How many patients survive for five years? • Ten babies are born today at a hospital. How many are females? Let X be the count of successful outcomes from a series of Bernoulli trials. We call X a binomial variable if the following assumptions hold: 1. There are a fixed number n of trials/observations. 2. The n observations are all independent. That is, knowing the result of one observation does not change the probabilities we assign to other observations. 3. Each observation falls into one of just two categories, which for convenience we call “success” and “failure.” 4. The probability of a success, call it p, is the same for each observation. 2.9 ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 5 Example 2.3 • An obstetrician oversees n single-birth babies. Each birth is either a female or a male. • Knowing the outcome of one birth does not change the probability of a female on any other birth (independent). • We define a female a “success” (arbitrary). • p is the probability of a female for each birth. • The number of females we count that are born (out of n) is a discrete random variable X and has a binomial distribution. 2.10 The Binomial Distribution • The count X of successes in the binomial setting has the binomial distribution with parameters n and p. The parameter n is the number of observations, and p is the probability of a success on any one observation. The possible values of X are the whole numbers from 0 to n. 2.11 3 Binomial Probabilities Now we would like to determine the probability that a binomial random variable X takes a specific value (say x). This is best described using an example: Example 2.4 , Blood Donations In the population served by the New York Blood Center, each blood donor has probability 0.45 of having blood type O. In the next 5 blood donations to the centre from unrelated individuals, what is the probability that exactly 2 of them have type O blood? The count of donors with type O blood is a binomial random variable X with n = 5 tries and probability p = 0.45 of a success on each try. We want P (X = 2). Let S = success (blood type O), F = failure (not blood type O). Here is one example of observing exactly 2 successes (blood type O) from the next 5 observations (donations): ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 6 . Notice that any arrangement of 2 successes and 3 failures (in 5 observations) has the same probability. Here are all the possible arrangements SSFFF FSFSF SFSFF FSFFS SFFSF FFSSF SFFFS FFSFS FSSFF FFFSS There are 10 total arrangements (each with the same probability) 2.12 Binomial Coefficient • If we were interested in the next 15 blood donations we could determine P (X = 2) following the pattern of example 2.4. However, listing all of the possible arrangements of 2 successes among n trials would be tedious. Instead we use the following fact: • The number of ways of arranging k successes among n observations is given by the binomial coefficient n n! = k k!(n − k)! for k = 0, 1, 2, . . . , n. Where n! =n × (n − 1) × (n − 2) × · · · × 3 × 2 × 1 • For example 2.4, X = 2, n = 5 2.13 ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 7 Binomial Probability • Based on the logic we used in example 2.4 we can now define a formula for the probability of a specific number of successes from a binomial distribution. • If X has the binomial distribution with n observations and probability p of success on each observation, the possible values of X are 0, 1, 2, . . . , n. If k is any one of these values, n k P (X = k) = p (1 − p)n−k k 2.14 Example 2.5 , Inspecting Pharmaceutical Containers A pharmaceutical company inspects a simple random sample (SRS) of 10 empty plastic containers from a shipment of 10,000 containers. The containers are examined for traces of benzene, a common chemical solvent but also a known human carcinogen. Suppose that (unknown to the company) 10% of the containers in the shipment contain traces of benzene. Count the number X of containers contaminated with benzene in the sample. 2.15 ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 8 This is not quite a binomial setting. Selecting one plastic container changes the proportion of contaminated containers remaining in the shipment: • The probability that the second container chosen is contaminated changes when we know that the first is contaminated. • Removing one container from a shipment of 10,000 changes the makeup of the remaining 9999 very little. • In practice, the distribution of X is very close to the binomial distribution with n = 10 and p = 0.1. Obtaining Binomial Probabilities • Similar to the Normal Distributions, we will typically obtain Binomial probabilities using technology or published tables. • RStudio offers functions to calculate the binomial probabilities (i.e. P (X = k)) or cumulative probabilities (i.e. P (X ≤ k)) • Continuing from example 2.5 in RStudio. 2.16 Exercise 2.1 , Blood Donations In the population served by the New York Blood Center, 45% have blood type O. Consider the next 15 blood donations to the center from unrelated individuals. (a) What is the probability that exactly 3 have blood type O? (b) What is the probability that 3 or fewer have blood type O? . ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 9 2.17 Example 2.6 An exciting computer game is released. Sixty percent of players complete all the levels. Thirty percent of them will then buy an advanced version of the game. Among 15 users, what is the probability that at least two people will buy the advanced version? Let X be the number of people (successes), among the mentioned 15 users (trials), who will buy the advanced version of the game. 2.18 ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 10 Example 2.7 , In-Class Exercise: ESP 2.19 ST230 (Part 2) 4 c David Soave, 2023 Page 11 The Hypergeometric Distribution Suppose that we are interested in the number of defectives in a sample of n units drawn without replacement from a lot containing N units, of which a are defective. At each draw, all remaining units are equally likely to be drawn. a . N • The probability that the second drawing will yield a defective unit is is a−1 a or , depending on whether or not the first unit drawn was N −1 N −1 defective. • The probability that the first drawing will yield a defective unit is • Thus, the trials are not independent, the third assumption underlying the binomial distribution is not met, and the binomial distribution does not apply. • Note* the binomial distribution would apply if we do sampling with replacement. I.e. if each unit selected for the sample is replaced before the next one is drawn. To solve this sampling without replacement problem, let X be the number of successes (defectives) chosen, then: • In how many ways can x successes be chosen? • In how many ways can n − x failures be chosen? • Thus the x successes and n − x failures can be chosen in • Finally, we know that n objects can be chosen from a set of N objects in Thus, the probability of getting “x successes in n trials” is ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 12 Hypergeometric Distribution Let X be the number of successes in a sample of size n selected (without replacement) from a population of size N containing a successes. Here, X has the hypergeometric distribution with parameters n, N, and a, where the probability that X = x is h(x; n, a, N ) = a x N −a n−x N n for x = 0, 1, . . . , n where x cannot exceed a and n − x cannot exceed N − a. 2.20 Example 2.8 An Internet-based company that sells discount accessories for cell phones often ships an excessive number of defective products. The company needs better control of quality. Suppose it has 20 identical car chargers on hand but that 5 are defective. If the company decides to randomly select 10 of these items, what is the probability that 2 of the 10 will be defective? 2.21 ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 13 Example 2.9 , example 2.5 cont. Recall example 2.5 where we calculated the probability that the sample contains no more than 1 contaminated container. There we assumed that X followed a binomial distribution. Re-calculate this probability assuming that X follows the hypergeometric distribution. 2.22 ST230 (Part 2) 5 c David Soave, 2023 Page 14 The Mean and Variance of a Probability Distribution Often we will want to describe certain characteristics of a distribution, and compare distributions with each other. The two most common characteristics that we describe are the location (or “center”) and variation (or “spread”). The most important statistical measures for describing these are the mean and variance. Example 2.10 Consider the histograms representing two binomial distribution functions (below). Visually, these distributions differ in terms of both their center and their spread. Figure 4.6 Johnson, Miller & Freund’s Probability and Statistics for Engineers, 9E, c Pearson 2.23 The Mean of a Discrete Probability Distribution The mean of a probability distribution is simply the mathematical expectation of a random variable having that distribution. If a random variable X takes on the values x1 , x2 , ..., or xk , with the probabilities f (x1 ), f (x2 ), ..., and f (xk ), its mathematical expectation or expected value is ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 15 µ =E(X) X = x · f (x) all x 2.24 Example 2.11 , Coin Tosses Find the mean of the probability distribution of the number of heads obtained in 3 flips of a balanced coin. 2.25 The Mean of a Binomial Distribution The mean of a binomial distribution with parameters n and p is simply µ =E(X) = np Proof: ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 16 Consider the figure with pdf b(x; n = 16, p = 1/2). For p = 1/2: • We “expect” half of the n = 16 trials to be successes. • So the mean of X should intuitively be 8 (or 16×1/2). 2.26 The Mean of a Hypergeometric Distribution The mean of a hypergeometric distribution with parameters n, N and a is simply µ =E(X) = n · a N Proof: 2.27 Example 2.12 , Lotto Max - Mean of Matching Numbers Find the mean (expected) count of matching numbers on a single Lotto Max line. Recall: each line on a Lotto Max ticked consists of seven numbers (between 1 and 49) with no repeats. 2.28 ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 17 The Variance of a Discrete Probability Distribution To consider the spread (or variation) of a distribution, it is intuitive to consider this in relation to the location of its mean. Figure 4.6 Johnson, Miller & Freund’s Probability and Statistics for Engineers, 9E, c Pearson Based on the formula for the mean, we define the variance of a probability distribution f (x) (or of a random variable X) as, X (x − µ)2 · f (x) σ2 = all x Due to the “squaring” of the deviations, σ 2 is not in the same units as X, so we correct this by taking the square root. Thus, the standard deviation is defined as sX σ= (x − µ)2 · f (x) all x Can we think of any other reasonable ways to define a formula for the variance (or spread)? 2.29 ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 18 Example 2.13 , Calculating Standard Deviations Calculate (and compare) the standard deviations of the two binomial distributions (in figure above). 2.30 The Variance of a Binomial Distribution The variance of a binomial distribution with parameters n and p is simply σ 2 =n · p · (1 − p) 2.31 Example 2.14 Recalculate (and compare) the standard deviations obtained in example 2.13 using the formula just given. ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 19 2.32 The Variance of a Hypergeometric Distribution The variance of a hypergeometric distribution with parameters n, N and a is simply a a N −n 2 σ =n 1− N N N −1 2.33 Example 2.15 , Lotto Max - Mean of Matching Numbers Refering to example 2.12, find the standard deviation of the probability distribution of the count of correct (matching) numbers in a single Lotto Max play/line. 2.34 ST230 (Part 2) 6 c David Soave, 2023 Page 20 The Poisson Distribution The Poisson distribution often serves as a model for counts which do not have a natural upper bound. It is an important probability distribution for describing the number of times an event randomly occurs in one unit of time or one unit of space. In one unit of time, each instant can be regarded as a potential trial in which the event may or may not occur. Although there are conceivably an infinite number of trials, usually only a few or moderate number of events take place. The Poisson Distribution The Poisson distribution with mean λ (lambda) has probabilities given by f (x; λ) = λx e−λ x! for x = 0, 1, 2, . . . λ>0 The mean and variance of the Poisson distribution are given by µ =λ σ2 = λ 2.35 Example 2.16 , Counts of Particles For health reasons, homes need to be inspected for radon gas which decays and produces alpha particles. One device counts the number of alpha particles that hit its detector. To a good approximation, in one area, the count for the next week follows a Poisson distribution with mean 1.3. Determine (a) the probability of exactly one particle next week. (b) the probability of one or more particles next week. (c) the probability of at least two but no more than four particles next week. (d) the variance of the Poisson distribution. ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 21 Figure 4.9 Johnson, Miller & Freund’s Probability and Statistics for Engineers, 9E, c Pearson 2.36 Modification of the Third Axiom of Probability Note that x = 0, 1, 2, . . . means there is a countable infinity of possibilities, and this requires that we modify the third axiom of probability given previously Axiom 30 . If A1 , A2 , A3 , . . . is a finite or infinite sequence of mutually exclusive events in S, then P (A1 ∪ A2 ∪ A3 ∪ · · · ) = P (A1 ) + P (A2 ) + P (A3 ) + · · · Using this modified rule, we can verify that P (S) = 1 for a Poisson distribution: 2.37 ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 22 The Poisson Approximation to the Binomial Distribution The Poisson distribution can be effectively used to approximate Binomial probabilities when the number of trials n is large, and the probability of success p is small. Such an approximation is adequate, say, for n ≥ 20 and p ≤ 0.05, and it becomes more accurate for larger n. When n → ∞, p → 0, while np = λ remains constant we have 2.38 ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 23 Exercise 2.2 Three percent of electronic messages are transmitted with an error. What is the probability that out of 200 messages, no more than 5 will be transmitted with an error? 2.39 ST230 (Part 2) 7 c David Soave, 2023 Page 24 The Geometric and Negative Binomial Distribution The Geometric Distribution With the binomial distribution, we are concerned with the number of successes X in a fixed number of Bernoulli trials n. Suppose, instead we are interested in the number of the trial X on which the first success occurs: If the first success comes on the xth trial, then it has to be preceded by x − 1 failures. If the probability of success for each independent trial is p then we get the following probability distribution for the geometric distribution: g(x; p) =p(1 − p)x−1 for x = 1, 2, 3, 4, . . . The corresponding mean and variance can be shown as µ= 1 p σ2 = 1−p p2 2.40 The Negative Binomial Distribution Now, suppose we are interested in the total number of the trials X required to obtain a specified number of successes r. If the rth success comes on the xth trial, then it has to be preceded by exactly r − 1 success in the first x − 1 trials. In addition, x − r failures must have also occured. If the probability of success for each independent trial is p then we the following probability distribution for the negative binomial distribution: x−1 r nb(x; r, p) = p (1 − p)x−r for x = r, r + 1, r + 2, . . . r−1 Note: ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 25 • We get the negative binomial distribution by multiplying the binomial probability b(r − 1; x − 1, p) and p. • For r = 1 this reduces to the geometric distribution. The corresponding mean and variance can be shown as µ= r p σ2 = (1 − p)r p2 2.41 Exercise 2.3 , Sequential Testing In a recent production, 5% of certain electronic components are defective. We need to find 12 non-defective components for our 12 new computers. Components are tested until 12 non-defective ones are found. What is the probability that more than 15 components will have to be tested? 2.42 ST230 (Part 2) c David Soave, 2023 Page 26 Next Time • Probability Densities 2.43 Homework Exercises Chapter 4 (Johnson, 9th ed.) • Exercises 4.79 to 4.95 (odd numbers only) 2.44