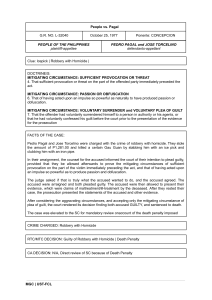

ARTICLE 11 Velasquez vs. People G.R. No.195021, March 15, 2017 FACTS: On May 24, 2003 in the evening, Velasquez (accused) while armed with stones and wooden poles, conspiring, confederating and mutually helping one another, with intent to kill, with treachery and abuse of superior strength, did, then and there willfully, unlawfully and feloniously attack, maul and hit Jesus del Mundo inflicting upon him injuries in the vital parts of his body, the said accused having thus commenced a felony directly by overt acts, but did not perform all the acts of execution which could have produced the crime of Murder but nevertheless did not produce it by reason of some causes or accident other than their own spontaneous desistance to his damage and prejudice. The accused invoke the first and second justifying circumstances under Article 11 of the Revised Penal Code reiterating that it was Jesus, who was supposedly inebriated, vented his ire upon Nicolas and the other accused, as well as on Mercedes. The accused thus responded and countered Jesus' attacks, leading to his injuries. Petitioners Nicolas Velasquez and Victor Velasquez, along with four others -Felix Caballeda, Jojo Del Mundo, Sonny Boy Velasquez, and Ampong Ocumen - were charged with attempted murder under Article 248, in relation to Article 6, of the Revised Penal Code. Issue: Whether or not petitioners may be held criminally liable for the physical harm inflicted on Jesus Del Mundo. Held: Yes. A person invoking self-defense (or defense of a relative) admits to having inflicted harm upon another person - a potential criminal act under Title Eight (Crimes Against Persons) of the Revised Penal Code. However, he or she makes the additional, defensive contention that even as he or she may have inflicted harm, he or she nevertheless incurred no criminal liability as the looming danger upon his or her own person (or that of his or her relative) justified the infliction of protective harm to an erstwhile aggressor. The accused's admission enables the prosecution to dispense with discharging its burden of proving that the accused performed acts, which would otherwise be the basis of criminal liability. All that remains to be established is whether the accused were justified in acting as he or she did. To this end, the accused's case must rise on its own merits: It is settled that when an accused admits harming the victim but invokes self-defense to escape criminal liability, the accused assumes the burden to establish his plea by credible, clear and convincing evidence; otherwise, conviction would follow from his admission that he harmed the victim. Selfdefense cannot be justifiably appreciated when uncorroborated by independent and competent evidence or when it is extremely doubtful by itself. Indeed, in invoking self-defense, the burden of evidence is shifted and the accused claiming self-defense must rely on the strength of his own evidence and not on the weakness of the prosecution. ART. 12 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES vs. PANTOJAG.R. No. 223114 November 29, 2017 FACTS: Prior to the commission of the crime, the accused had already exhibited signs of mental illnesswhich started manifesting after he was mauled by several persons in an altercation when he wastwenty-one (21) years old. Because of the incident, he sustained head injuries, which requiredstitches. No further physical examination was conducted on him, because they did not have the fundsto pay for additional checkups. Cederina, mother of the accused, observed that his personality hadchanged, and he had a hard time sleeping. There was a time when he did not sleep at all for oneweek, prompting Cederina to bring the accused-appellant to the psychiatric department of thePhilippine General Hospital (PGH). There, the attending physician diagnosed him with schizophrenia.On July 14, 2010 at 7:45 in the evening, the accused was able to escape from the hospital andarrived at their house the day after. Cederina asked herein accused how he was able to find his wayhome, the accused responded that he roamed around until he remembered the track towards theirway home. Cederina reported to PGH that he has custody of his son, the latter advised that shereturn his son but was not able to do so because they could not afford the transportation expenses.On 22 July 2010, at around 8:00 o'clock in the morning, Cederina and the accused-appellantwere inside their house. Eventually, she noticed that accused-appellant was gone. She went outsideto look for him and noticed that the front door of the house where six-year-old AAA resided was open.She then saw accused-appellant holding a knife and the victim sprawled on the floor, bloodied.Dr. Nulud testified that he conducted an autopsy on the victim. His examination revealed thatthe victim sustained four (4) stab wounds: on his forehead, his neck, his right shoulder, and below hiscollar bone. The RTC then found the accused guilty beyond reasonable doubt of the crime of murderand sentenced him to suffer the penalty of reclusion perpetua. On appeal, the CA affirmed thedecision of the lower court. ISSUE: Whether accused-appellant has clearly and convincingly proven his defense of insanity toexempt him from criminal liability HELD: The Supreme saw no reason to overturn the decision of the CA. A scrutiny of the evidencepresented by accused-appellant unfortunately fails to establish that he was completely bereft ofreason or discernment and freedom of will when he fatally stabbed the victim. Cederina tends to showthat accused-appellant exhibited signs of mental illness only after being injured in an altercation in2003; that she observed changes in his personality and knew he had difficulty sleeping since then;that accused-appellant was confined in the hospital a few times over the years for his mental issues;and that he was confined at the NCMH on 8 July 2010 from where he subsequently escaped. Nothingin her testimony pointed to any behavior of the accused-appellant at the time of the incident inquestion, or in the days and hours before the incident, which could establish that he was insane whenhe committed the offense. ART. 13 G.R. No. L-48976 October 11, 1943 THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, plaintiff-appellee, vs. MORO MACBUL, defendant-appellant. Cesar C. Climaco for appellant. Office of the Solicitor General De la Costa and Solicitor Madamba for appellee. OZAETA, J.: Appellant pleaded guilty to an information for theft of two sacks of papers valued at P10 belong to the Provincial Government of Sulu, alleged to have been committed on March 9, 1943, in the municipality of Jolo; it being also alleged that he was a habitual delinquent, having been twice convicted of the same crime on November 14, 1928, and August 20, 1942. The trial court sentenced him to suffer one month and one day of arresto mayor as principal penalty and two years, four months, and one day of prision correccional as additional penalty for habitual delinquency. The trial court found two mitigating circumstances: plea of guilty under paragraph 7, and extreme poverty and necessity under paragraph 10, of article 13 of the Revised Penal Code; but it took into account the aggravating circumstance of recidivism in imposing the principal as well as the additional penalty. The only question raised here by counsel for the appellant is the correctness of the consideration by the trial court of recidivism as an aggravating circumstance for the purpose of imposing the additional penalty for habitual delinquency, counsel contending that recidivism should not have been taken into account because it is inherent in habitual delinquency. While that contention is correct, as we have decided in the case of People vs. Tolentino, 1 Off. Gaz., 682, it is beside the point here because the error committed by the trial court lies not so much in its having considered recidivism as an aggravating circumstance for the purpose of penalizing habitual delinquency, as in its having considered appellant as a habitual delinquent at all, it appearing from the information that his two previous convictions were more than ten years apart. "A person shall be deems to be habitually delinquent, if within a period of ten years from the date of his release or last conviction of the crimes of robo, hurto, estafa, or falsification, he is found guilty of any of said crimes a third time or oftener." (See last paragraph, article 62, No. 5, of the Revised Penal Code.) Therefore, appellant's first conviction, which took place in November, 1928, cannot be taken into account because his second conviction took place in August, 1942, or fourteen years later. Hence within the purview of the Habitual Delinquency Law appellant has only one previous conviction against him, namely, that of 1942. The trial court considered extreme poverty and necessity as a mitigating circumstance falling within No. 10 of article 13 of the Revised Penal Code, which authorizes the court to consider in favor of an accused "any other circumstance of a similar nature and analogous to those above mentioned." The trial court predicates such consideration upon its finding that the accused, on account of extreme poverty and of the economic difficulties brought about by the present cataclysm, was forced to pilfer the two sacks of papers mentioned in the information from the Customhouse Building, which he sold for P2.50, in order to be able to buy something to eat for various minor children of his. (The stolen goods were subsequently recovered.) The Solicitor General interposes no objection to the consideration of such circumstance as mitigating under No. 10 of article 13. We give it our stamp of approval, recognizing the immanent principle that the right to life is more sacred than a mere property right. That is not to encourage or even countenance theft but merely to dull somewhat the keen and pain-producing edges of the stark realities of life. Conformably to the recommendation of the Solicitor General, the sentence appealed from is modified by affirming the principal penalty and eliminating the additional penalty, without costs. Yulo, C.J., Moran and Paras, JJ., concur. Separate Opinions BOCOBO, J., concurring: I concur in the result. In view of the far-reaching significance of the doctrine enunciated in the foregoing opinion — that extreme poverty is a mitigating circumstance — and of the fact that such a rule deviates from established precedents, I deem it appropriate to set forth my reasons for subscribing to the new principle. I believe that extreme poverty and necessity is a mitigating circumstance, not only because it is analogous mitigating circumstance under No. 10 of art. 13 of the Revised Penal Code, as stated in the above opinion, but also for the reason that it is an incomplete exempting circumstance contemplated in No. 1 of said article 13, in relation to Nos. 5 (irresistable force) and 6 (uncontrollable fear) of art. 12. The trial court found that the accused committed the crime of theft "por extrema pobreza y necesidad," and considered this as an analogous mitigating circumstance within the meaning of No. 10, art. 13 of the Revised Penal Code. Such a finding is based on the fact that on March 9, 1943, the accused took the two sacks of papers and sold the same for P2.50 because he is the father of several minor children and they and he had nothing to eat on that day. The Supreme Tribunal of Spain has refused to recognize extreme poverty as a mitigating circumstance by analogy in cases of robbery and theft. (See sentences of April 20, 1871; July 12, 1904; April 18, 1907; and July 9, 1907).lawphil.net As for Philippine jurisprudence, as far as I know, this question has never been squarely passed upon by this court. Possibly one of the reasons is that in view of the well-established doctrine of the Spanish Supreme Court, above referred to, it seems to have been taken for granted by the legal profession here that extreme poverty and need is not a mitigating circumstance by analogy in cases of robbery and theft. In spite of precedents and widespread belief to the contrary, I do not hesitate to hold the proposition that extreme poverty and need is a mitigating circumstance analogous to two of the circumstances enumerated in art. 13. These two are: 1. "That of having acted upon an impulse so powerful as naturally to have produced passion or obfuscation." (No. 6) 2. "Such illness of the offender as would diminish the exercise of will-power without however depriving him of consciousness of his acts." (No. 9) It will be noted that there is a common idea underlying these two mitigating circumstances, namely, that the offender either by a powerful impulse or through illness had no effective control over himself at the time he committed the crime. Was this the state of mind of the defendant herein when he took the papers? I believe so because the thought that his little children would starve on that day must have temporarily dulled his conscience and driven him to steal. The spectre of hunger of his loved ones terrified him into stealing. The reason for Nos. 6 and 9 of art. 13, above quoted, being the same as in the instant case, the rule of analogy authorized in No. 10 of that article should be applied. The ancient principle upheld by the Roman jurists, Eadem dispositio, ubi eadem ratio is a puissant logic and is eminently just. Furthermore, the facts of this case come within the purview of No. 1 of art. 13, which provides: Art. 13. Mitigating circumstances. — The following are mitigating circumstances: 1. Those mentioned in the preceding chapter, when all the requisites necessary to justify the act or to exempt from criminal liability in the respective cases are not attendant. In other words, the offense of the accused herein may be properly considered as mitigated by incomplete exemption from criminal liability, under Nos. 5 and 6 of art. 12, (irresistible force and uncontrollable fear of an equal or greater injury.) The first question in this aspect of the case is whether No. 1 of art. 13 refers only to those exempting circumstances which contain two or more requisites (self-defense, defense of relatives or of stranger, and avoidance of an evil or injury in Nos. 1 to 4, art. 11.) The answer is negative because No. 1 of art. 13 refers to the preceding chapter relative to justifying and exempting circumstances, and the preceding chapter, which consists of art. 11 and 12, includes circumstances which are not composed of several requisites. In People vs. Oanis, G.R. No. 47722, (July 27, 1943) we held that improper performance of a duty (No. 5, art. 11) is mitigating circumstance. Coming now to irresistible force, No. 5 of art. 12 provides that "any person who acts under the compulsion of an irresistible force" is exempt from criminal liability. It is true that according to the doctrine of the Supreme Tribunal of Spain, the irresistible force must be external, proceeding from a third person (S. of Feb. 28, 1891). But considering that the law makes no distinction between force within the accused himself and from another person, and that one type of force is just as compelling as another, I think it is but right to hold that such force need not be exerted by another person. This being so, why should the offense of the accused herein be mitigated by extreme poverty and need? Because misery and hunger impelled him to steal, although such force was not absolutely irresistible, under No. 5 of art. 12. His condition was sufficiently grave to drive him to take the papers, but it was not utterly inevitable that he should do so. The same considerations apply in regard to uncontrollable fear of an equal or greater injury (No. 6, art. 12). The accused, desperate because of fear that his little children would starve, stole the papers, but his fear was not absolutely uncontrollable. Taking irresistible force and uncontrollable fear together, I believe that the force and the fear which coerced the accused herein to steal are of the same nature contemplated in Nos. 5 and 6 of art. 12, but they are of less degree than that required for complete exemption from criminal responsibility. Therefore, I am of the opinion that according to No. 1 of art. 13, there is a mitigating circumstance of incomplete exemption from criminal liability under Nos. 5 and 6 of art. 12 of the Revised Penal Code. I am not unmindful of the possible objection that the doctrine herein enunciated may encourage theft and robbery and undermines the right of property, and is therefore revolutionary. But so long as extreme poverty and need is not declared an exempting but only a mitigating circumstance, the rule herein announced is fully warranted. The crime itself is condemned, though the punishment is tempered. It can not be successfully contended that a mitigating circumstance fosters crime. It is easy to understand the conservatism of the precedents and of the attitude of the legal profession, but considerable water has flowed under the bridge during the last two decades. Governments and peoples all over the world have visualized more clearly the sufferings and hardships of the poor. Humanitarian ideas have loomed larger on the horizon. More and more, legislation in all countries has been removing from the bending backs of the underprivileged the unbearable burdens which had been crushing and overwhelming their existence. More and more, lawmaking bodies throughout the world have seen to it that the toiling masses participate, as much as possible, in the good things of life. More and more, legislatures have realized that extreme poverty is brought about by general social conditions and through no fault of the poor. More and more, legislation has remedied the sinister state of affairs which seemed to consider poverty a crime. Therefore, the original interpretation of laws must give way to a new one, which should be attuned to the spirit of the age all over the earth. Although the wording of the articles of the Penal Code under discussion has not been changed, their interpretation may be changed in order that they may not become anachronistic. Considering that social conditions often unfold faster than legislation, it is a salutary function of old laws as to adjust them to contemporary exigencies of the public weal. This is not judicial legislation at all because the lawmakers intended that the law which they approved should govern for many years to come, and that therefore it should be interpreted by the courts in such a way as to meet new problems, provided the fundamental objectives of the law are distinctly kept in view. In the instant case, theft is punished, so the principle of crime repression is carried out; and the penalty is moderated because of extreme poverty and need, so the idea of punishment according to the circumstances of each case is also recognized. Finally, so long as there is widespread unemployment and so long as relief work, both private and governmental, is inadequate, the punishment for stealing because of hunger should be lessened, but not waived or lifted. Unless and until there is a job for every person willing to work, to mete out the ordinary or highest penalty for stealing due to dire necessity flies in the face of the principle of social justice. It is tantamount to exacting the pound of flesh in accordance with the letter of the law. The foregoing considerations are strengthened by the leeway given to the courts in determining what in each case constitutes a mitigating circumstance by analogy. The lawmaker, fully aware of the impossibility of laying down an exhaustive enumeration of circumstances that would extenuate crime, has formulated a general statement in No. 10 of art. 13. It is thus that each case must be judged by the courts on its own merits, the only condition being that there must be similarity or analogy to one or more of the nine circumstances specifically mentioned in said art. 13. Commenting on a similar provision of the Spanish Penal Code (No. 8, art. 9), Groizard makes these observations: Recuerdense una por una las siete circunstancias atenuantes que ya llevamos examinadas, y se advertira la exactitud de lo que venimos diciendo. Todas y cada una son generalizaciones y en todas se hallara que la libertad, o la inteligencia, o la intencion aparecen mutiladas en bastante grado para influir en la responsabilidad de los actos humanos. Descender a demostrar esta verdad, lo tenemos por inutil: su evidencia no han de ponerla en duda los que recuerden el texto de los numeros y el espiritu que las vivifica. Pero ese estudio amplio, vastisimo; estudio en el cual parece que se pierde el hombre dentro de la humanidad; esas grandes corrientes, puntos cardinales, moldes en que todos se funden, aunque el legislador crea que lo abarcan todo, podria suceder que se equivocase, y logico en su aspiracion de ser un reflejo de la justicia moral, al trazar el circulo en que queda a salvo el principio de que parte, en prevision de que algun caso quedase sin definir y fuera de las clasificaciones hechas, que ni por su generalidad, ni por su alcance, pudiera engendrar una regla de aplicacion constante, un canon, fue preciso establecer el unico criterio que pudiera apreciarle con entera conciencia: aludimos al criterio de los Tribunales. De aqui la circunstancia 8.a, que, en rigor, no es mas que una regla generica para todo lo que hallandose fuera del cuadro de las anteriormente formuladas pudiera correr igual suerte que estas, cuando lo exigieran igual identidad y analogia, El Codigo Penal de 1870, Concordado y Comentado, Vol. 1, p. 401. (Emphasis supplied). Although perhaps many decades will have to elapse before penal codes of the world recognize extreme poverty and need as an exempting circumstance, yet I believe that in the meantime it is in keeping with the humanitarian ideas of this generation to recognize the cruel pangs of hunger as a factor that mitigates the penalty. Possibly the growing atmosphere favorable to the submerged classes will eventually uphold the stand of Judge Paul Magnaud who about fifty years ago became popularly known in France as the "bon judge" because of his significant decisions acquitting those who had been impelled to steal on account of the excruciating tortures of hunger. Be that as it may, I am convinced that the doctrine herein declared responds to the heart-throbs of mankind. All in all, I am persuaded that the principal penalty fixed by the trial court, one month and one day of arresto mayor, extreme poverty and need having been considered as a mitigating circumstance by analogy, fits the facts of the instant case. ART. 14 PEOPLE v. THEODORE BERNAL, GR No. 113685, 1997-06-19 Facts: Theodore Bernal, together with two other persons whose identities and whereabouts are still unknown, were charged with the crime of kidnapping... one Bienvenido Openda, Jr. A plea of not guilty having been entered by Bernal during his arraignment, trial ensued. The prosecution presented four witnesse On the other hand, Theodore Bernal testified for his defense. around 11:30 in the morning, while Roberto Racasa and Openda, Jr. were engaged in a drinking spree, they invited Bernal, who was passing by, to join them. After a few minutes, Bernal decided to leave both men, apparently because he was going to fetch his child. Thereafter, two men arrived, approached Openda, Jr., and asked the latter if he was "Payat."[3] When he said yes, one of them suddenly pulled out a... handgun while the other handcuffed him and told him "not to run because they were policemen" and because he had an "atraso" or a score to settle with them. They then hastily took him away. Racasa immediately went to the house of Openda, Jr. and informed the latter's mother of... the abduction. theory of the prosecution, as culled from the testimony of a certain Salito Enriquez, tends to establish that Openda, Jr. had an illicit affair with Bernal's wife Naty and this was the motive behind the former's kidnapping. Until now, Openda, Jr. is still missing. defense asserts that Openda, Jr. was a drug-pusher arrested by the police on August 5, 1991, and hence, was never kidnapped... court a quo rendered judgment[5] finding Bernal "guilty... crime of kidnapping for the abduction and disappearance of Bienvenido Openda, Jr... important is the testimony of Roberto Racasa He narrated that he and the victim were drinking at "Tarsing's Store" on that fateful day when Bernal passed by... and had a drink with them. After a few minutes, Bernal decided to leave, after which, two men came to the store and asked for "Payat." When Openda, Jr. confirmed that he was indeed "Payat," he was handcuffed and taken away by the unidentified men Salito Enriquez, a tailor and a friend of Openda, Jr., testified Openda, Jr. confided to him that he and Bernal's wife Naty were having an affair. One time, Naty even gave Openda, Jr. money which they used to pay for a motel... room. He advised Naty "not to do it again because she (was) a married woman.[9] Undoubtedly, his wife's infidelity was ample reason for Bernal to contemplate revenge. Issues: Bernal assails the lower court for giving weight and credence to the prosecution witnesses' allegedly illusory testimonies and for convicting him when his guilt was not proved beyond reasonable doubt. Openda, Jr.'s revelation to Enriquez regarding his illicit relationship with Bernal's wife is admissible in evidence Ruling: We find no compelling reason to overturn the decision of the lower court. In the case at bar, Bernal indisputably acted in conspiracy with the two other unknown individuals "as shown by their concerted... acts evidentiary of a unity of thought and community of purpose."[7] Proof of conspiracy is perhaps most frequently made by evidence of a chain of circumstances only.[8] The circumstances present in this case sufficiently indicate the... participation of Bernal in the disappearance of Openda, Jr. Openda, Jr.'s revelation to Enriquez regarding his illicit relationship with Bernal's wife is admissible in evidence Openda, Jr., having been missing since his abduction, cannot be called upon to testify. His confession to Enriquez, definitely a declaration against his own interest, since his affair with Naty Bernal was a crime, is admissible in evidence[13] because no... sane person will be presumed to tell a falsehood to his own detriment. Principles: Motive is generally irrelevant, unless it is utilized in establishing the identity of the perpetrator. Coupled with enough circumstantial evidence or facts from which it may be reasonably inferred that the accused was the malefactor, motive may be sufficient to support a... conviction... pursuant to Section 38, Rule 130 of the Revised Rules on Evidence, viz.: "Sec. 38. Declaration against interest. -- The declaration made by a person deceased, or unable to testify, against the interest of the declarant, if the fact asserted in the declaration was at the time it was made so far contrary to declarant's own interest,... that a reasonable man in his position would not have made the declaration unless he believed it to be true, may be received in evidence against himself or his successors-in-interest and against third persons." With the deletion of the phrase "pecuniary or moral interest" from the present provision, it is safe to assume that "declaration against interest" has been expanded to include all kinds of interest, that is, pecuniary, proprietary, moral or even penal A statement may be admissible when it complies with the following requisites, to wit: "(1) that the declarant is dead or unable to testify; (2) that it relates to a fact against the interest of the declarant; (3) that at the time he made said declaration the declarant was aware... that the same was contrary to his aforesaid interest; and (4) that the declarant had no motive to falsify and believed such declaration to be true." ART. 15 PEOPLE VS. APDUHAN, JR. G.R. No. L-19491, August 30, 1968 24 SCRA 798 CASTRO, J: FACTS: On 23 May 1961, Apolonio Apduhan together with five others, armed with unlicensed firearms, and helping one another with violence, entered and robbed the house of the spouses Honorato Miano and Antonia Miano, in which they attack and shoot Geronimo Miano and Norberto Aton. In the trial, Apolonio Apduhan changed his plea from not guilty, with the condition that death penalty will not be imposed to him, and instead just life imprisonment. The case was reopened. The trial judge recommends to the President of the R-epublic the commutation of the death sentence which he imposed on the accused to life imprisonment. The Solicitor General supports this recommendation for executive clemency. ISSUE: Whether or not the trial court is correct in penalizing Apduhan for death after he pleaded guilty in the crime robbery with homicide, appreciating band? HELD: No, the trial court is incorrect in penalizing Apduhan for death after he pleaded guilty in the crime robbery with homicide, appreciating band. As previously stated, art. 295 provides that if any of the classes of robbery described in subdivisions 3, 4, and 5 of art. 294 is committed by a band, the offender shall be punished by the maximum period of the proper penalty. Correspondingly, the immediately following provisions of art. 296 define the term "band", prescribe the collective liability of the members of the band, and state that "when any of the arms used in the commission of the offense be an unlicensed firearm, the penalty to be imposed upon all the malefactors shall be the maximum of the corresponding penalty provided by law." Viewed from the contextual relation of articles 295 and 296, the word "offense" mentioned in the above-quoted portion of the latter article logically means the crime of robbery committed by a band, as the phrase "all the malefactors" indubitably refers to the members of the band and the phrase "the corresponding penalty provided by law" relates to the offenses of robbery described in the last three subdivisions of art. 294 which are all encompassed within the ambit of art. 295. Evidently, therefore, art. 296 in its entirety is designed to amplify and modify the provision on robbery in band which is nowhere to be found but in art. 295 in relation to subdivisions 3, 4, and 5 of art. 294. Verily, in order that the aforesaid special aggravating circumstance of use of unlicensed firearm may be appreciated to justify the imposition of the maximum period of the proper penalty, it is a condition sine qua non that the offense charged be robbery committed by a band within the contemplation of art. 295. To reiterate, since art. 295 does not apply to subdivisions 1 and 2 of art. 294, then the special aggravating factor in question, which is solely applicable to robbery in band under art. 295, cannot be considered in fixing the penalty imposable for robbery with homicide under art. 294(1), even if the said crime was committed by a band with the use of unlicensed firearms. The special aggravating circumstance of use of unlicensed firearm, however, was initially applicable to all the subdivisions of art. 294 since the -said Rep. Act No. 12 also amended art. 295 to include within its scope all the classes of robbery described in art. 294. With the then enlarged coverage of art, 295, art. 296, being corollary to the former, was perforce made applicable to robbery with homicide (art. 294[1]). Thus, in People v. B-ersamin (See note 3), this Court, in passing, opined: "The use of unlicensed firearm is a special aggravating circumstance applicable only in cases of robbery in band (Art. 296, Revised Penal Code, as amended by section 3, Republic Act No. 12)." Supreme Court’s decision with the modification that the death sentence imposed upon Apolonio Apduhan, Jr. by the court a quo is reduced to reclusion perpetua, the judgment a quo is affirmed in all other respects, without pronouncement as to costs