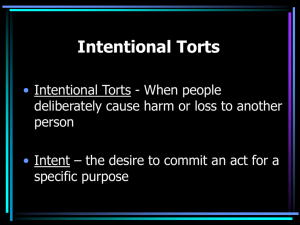

UNIVERSITY OF GUYANA FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF LAW LAW 13 A – LAW OF TORTS I Worksheet #2 - TRESPASS TO THE PERSON INTRODUCTION A. Trespass to the person 1. Trespass to the person consists of: (a) Assault (b) Battery (c) False Imprisonment Trespass to person: i.e. assault, battery and false imprisonment all must be committed intentionally, by direct and immediate actions and are actionable without proof of damage. The common element of these three torts is that the tort must be committed by direct means. There is also an analogous tort embodied in the case of: Wilkinson v Downton 1897 2 QB 57 (discussed later) ASSAULT A person commits an assault if he intentionally causes another reasonably to apprehen d the application of immediate unlawful force on his person: Letang v Cooper [1964]; Co llins v Wilcock [1984] 3 All ER 374. Winfield and Jolowicz: An assault is an act of the defendant which causes a plaintiff rea sonable apprehension of an infliction of a battery on him by the defendant. Kodilinye, Commonwealth Caribbean Tort Law – “An assault is a direct threat made by the defendant to the plaintiff, the effect of which is to put the plaintiff in reasonable fear or apprehension of immediate physical contact wit h his person.” 1 REQUIREMENTS OF ASSAULT 1.Reasonable apprehension of harm: C does not have to be afraid; just reasonably apprehend the contact; It is irrelevant that C is courageous, not frightened… or could easily defend himself. 2. Force apprehended must be immediate: if C has no reasonable belief that D had the present ability to effect his purpose then no assault is committed. Thomas v NUM (South Wales Area) [1986] NB this depends on the facts of each individual case. See Smith v Chief v Chief Superintendent of Working Police Station [1983]. Court h eld it was an assault to stand outside P house and stare in while she was wearing nothi ng but night clothing with the intend to frighten her and. See also R v Ireland and Burstow [1998]. Also, In Stephens v Meyer (1830), D attempt a blow on C which was intercepted by a thi rd-party Court found that this was assault. If C knows that threat will not be carried out there can be no assault as there will have b een no reasonable apprehension of contact: Tubervell v Savage (1669) Murray v Ministry of Health [1985] R v St George (1840) 3. It must be intentional D intends C to apprehend reasonable force would be used or was reckless as to the co nsequence of his or her action. NB- Words can negate an assault: as in Turberville v Savage (1669), where D said “If it were not assize time I would not take such language from you”; However, where the treat is conditional, it may result in assault: in Read v Coker (1853); D liablewhere he and his servant threaten to break the P’s neck if he did not leave the s hop. In R v Wilson [1995] it was considered that the word: “get out the knives” could result in an assault; See also R v Ireland and Burstow [1998] NB- Stevens v Myers 1830 4 C & P 349; (1830) 172 ER 735 Thomas v National Union of Mineworkers 1986 Ch 20 Blake v Barnard 1840 C&P 626 R v St George 1840 9 C&P 483 Hull v Ellis 2 Smith v Chief Supt 1983 76 Cr App R 234 BATTERY This is ‘the intentional and direct application of force [personal contact is unnecessary] to another person (without lawful justification)’ Requirement of battery 1) It must be intentional: For battery there must be a voluntary action by D, not an omission: Fagan v MPC [1969] For D to be liable of battery his conduct must be voluntary and it must be proved on a b alance of probabilities that D intended to bring about the contact thus D will be liable ev en if the consequence was not foreseeable: Willaim v Humprey [1975] D was liable for deliberately pushing a guess in the swimming pool though he did not int end to cripple P who break his ankle. In this context intention included subjective recklessness: R v Savage [1992] and in Bici v MOH [2004]: “D appreciated the potential harm to C and was indifferent to it” Battery even if original action unintended, if D at some point intended to apply force: Fa gan v MPC [1969] If the contact is intentional and direct, a mistaken belief that it is lawful is irrelevant. In P oland v John Parr and Sons [1927] 1 KB 236 where an employee thought he saw a boy stealing sugar from his employer’s cart and attacked the boy, there was a battery. ii. Direct- It must be Direct: however, this was interpreted flexibly e.g. Scott v Shepher d (1773) and DPP v K [1990]Fagan v Metropolitan Police Commissioner 1968 3 AER 442, 445 James J : “Where an assault involves a battery, it matters not in our judgment whether the battery is inflicted directly by the body of the offender or through the medium of some weapon o r instrument controlled by the action of the offender. An assault may be committed by th e laying of a hand upon another, and the action does not cease to be an assault if it is a stick held in the hand and not the hand itself which is laid upon the person of the victim. So for our part we see no difference in principle bet the action of stepping on to a perso n’s toe and maintaining that position and the action of driving a car on to a person’s foot and sitting in the car while its position on the foot is maintained.” 3 iii. Force. The least touching of another in anger is battery: Cole v Turner [1704]; on this basis the CA held battery must be committed with “hostile” intent: Wilson v Pringle [198 6] Winfield & Jolowicz“Any physical contact with the body of the plaintiff (or his clothing) is sufficient to amoun t to force: there is battery when a defendant shoots a plaintiff from a distance just as much a s when he strikes him with his fist. …mere passive obstruction, however, is not a battery ” Cole v Turner 6 Mod 149 Innes v Wylie 1844 1 C&K 257, 263 Donelly v Jackman 1970 1 AER 987 Wilson v Pringle 1984 2 AER 440 Collins v Wilcox F v West Berkshire Health Authority 1989 2 AER 545/ Re F (Mental patient sterilisation) [1990] 2 AC 1 iv. Hostility- What is hostile creates problem thus Robert Golf LJ in Collins v Wilcock [1 984] took the view that the law should exclude liability for conduct generally accepted in the ordinary conduct of daily life- he reiterated this in RE F [1990] Cole v Turner Wilson v Pringle F v West Berkshire Health Authority 1989 2 AER 545/ Re F (Mental patient sterilisation) [1990] 2 AC 1 R v Brown 1994 v. Without Consent Chatterton v Gerson 1981 QB 432 Freeman v Home Officer No 2 1984 QB 524 vi. Without Lawful Excuse F v West Berkshire Health Authority 1989 2 AER 545/ Re F (Mental patient sterilization) [1990] 2 AC 1 ASSAULT AND BATTERY DISTINGUISHED Collins v Wilcock 1984 3 AER 374: Goff LJ in this case defined an Assault as 4 “an act which causes another person to apprehend the infliction of immediate unlawful fo rce on his person” while a Battery is “the actual infliction of unlawful force on another per son”. Goff LJ went on to state that the fundamental principle is that any person's body is invio late, except in situations where the bodily contact "[falls] within a general exception emb racing all physical contact which is generally acceptable in the ordinary conduct of daily life". These are two separate torts although in popular usage assault is used to cover both tor ts. See: Fagan v Metropolitan Police Comm. 1968 3 AER 442, 445 James J: “for practical purposes today “assault” is generally synonymous with battery and is a ter m used to mean the actual intended use of unlawful force to another person without his co nsent”. In tort :assault involves putting another person in fear of being struck- it does not need t o involve actual striking; whereas battery involves striking the person or body of someon e else. Defences 1. Consent Consent maybe expressed where the plaintiff either orally or in writing agrees to a partic ular trespass, for example, where a patient enters the hospital for surgery – Chatterton v Gerson 1981 QB 432 Freeman v Home Office 1984 QB 524 Colby v Schmidt 1986 37 CCLT 3 Condon v Bassi 1985 1 WLR 866 Murphy v Colhane 1977 QB 94 R v Brown 1992 2 AER 552;1993 2 AER 75; Freeman v Home Office 1984 QB 524 2. Necessity F v West Berks Health Authority 1989 12 AER 545 Leigh v Gladstone 1909 26 TLR 139 Re T 1992 4 AER 649 5 3. Self Defence/Defence of property Lane v Holloway 1967 3 AER 129; 1968 1 QB 379 Revill v Newberry 1996 1 291 4. Acting in support of Lawful/statutory authority (arrest) 5. Exercise of Parental or other authority Mayers v AG of Barbados 1231 of 1991 High Court of Barbados unreported 6. Provocation Lane v Holloway 1967 3 AER 129; 1968 1 QB 379 Murphy v Colhane 1977 QB 94 7. Contributory Negligence Hoeburger v Coppens 1977 2 NZLR 597 Sayers v Harlow 1958 1 WLR 623 FALSE IMPRISONMENT: False imprisonment is the intentional deprivation of the claimant’s freedom of movement from a particular place for any time, however short unless expressly or impliedly authori zed by the law. Meering v Graham-White Aviation Co. Ltd. [1919] 122 LT 44- The passage in Termes d e la Lay was approved by Atkin and Duke LJJ. False Imprisonment is the imposition of a total restraint for some period, however short upon the liberty of another without lawful justification. Note that there need not be an act ual imprisonment nor is force necessary. “False” means wrongful, so that a wrongful arr est will be false imprisonment. The claimant must prove that he or she was intentionally denied freedom of mov ement but where a defendant claims that the restraint was lawful the burden is on the d efendant to justify this. False imprisonment must involve complete restriction on C’s freedom of moveme nt, this was not the case in Bird v Jones (1845) as even though C was barred from usin g the fence part of the bridge, he could have crossed on the unfence part; NB If there is an escape route but it’s not a reasonable one then the tort is committed. If there are conditions of leaving premises agreed by others, it may not be False I mprisonment. 6 Such was the case in Robinson v Balmain Ferry Co. Ltd [1910] AC 295 the claimant pai d one penny to enter a wharf in order to catch a ferry but then realized that there was a 20-minute wait for the next ferry. There was a charge of one penny for leaving the wharf – stipulated on a notice above the turnstile – and the defendants refused to let him leav e until he had paid the charge. The Privy Council held that there was no false imprisonment. In Herd v Weardale Steel, Coal and Coke Co. Ltd [1915] AC 67 the claimant, a miner, d emanded (in breach of his contract of employment) to be taken to the surface before the end of the normal shift. His employers (the defendant) refused. The House of Lords hel d: the defendant was not liable, partly because he (the claimant) had impliedly consente d to remain until the shift ended. The restraint must be actual rather than potential; see R v Bournewood Communi ty and Mental Health NHS Trust ex parte L [1998] 3 ALL ER 28 FI may be from anywhere from which C does not have a reasonable means of es cape. • a coalmine: Herd v Weardale Coal co. [1915], • a bridge: Bird v Jones and • possibly even public lavatory: Sayers v Harlow Urban District Council [1958] - C awareness of imprisonment: • If C too ill an action of FI will still lie: Grainger v Hill (1838). • It is unnecessary whether C was aware or not of the FI: Meering v Grahame-Whit e Aviation (1919); the claim can lie even if C does not know he/she is been detained More recently in Murray v Ministry of Defense [1988] Lord Griffiths expressed agreemen t with Lord Atkins in Meering. Where a prisoner is detained for extra days due to wrong calculation, the same is entitled to damages for FI: R v Governor of Brockhill Prison ex parte Evans (No 2) [200 0] However, this case was distinguished in Quinland v Governor of Swaleside Prison [200 3] 1 All ER 1173 where the governors had not made any arithmetical or other errors. Th e warrant specified the incorrect, longer sentence and they were, therefore, not at liberty to release the claimant any earlier. 7 -Sayers v Harlow Urban District Council 1958 1 WLR 523. "The concept of 'intention' in the intentional torts does not require defendants to know th at their acts will result in harm to the plaintiffs. Defendants must know only that their act s will result in certain consequences" Like the other forms of trespass to the person it is actionable per se. In Murray v Ministr y of Defense [1988] 1 WLR 692 Lord Griffiths commented (obiter) that: ‘the law attaches supreme importance to the liberty of the individual and if he suffers a wrongful interference with that liberty it should remain actionable even without proof of s pecial damage’ - Proof that such physical restraint is wrongful or not legally justified. False Impriso nment seeks to provide a cause of action where someone has been physically re strained and the restraint does not constitute that which is lawful Liversidge v Anderson [1942] AC 206 at 245 Lord Atkin: “in English law every imprison ment is prima facie unlawful and it is for a person directing an imprisonment to justify his act.” Jangoo v Gomez 1984 High Court, Trinidad and Tobago, No. 2652 of 1978 (unreported) - Mustapha Ibrahim J: “A claim for False imprisonment…is really an action of trespass t o the person. Once the trespass is admitted or proved, it is for the defendant to justify th e trespass.(see the judgment of Goddard LJ in Dumbell v Roberts 1944 1 AER 326 at p 931)” DEFENCES TO FALSE IMPRISONMENT The various elements of the defences are directly related to the broad elements and sub -elements of the tort in question. Thus, if one can show that either: a. The physical restraint was not legally sufficientnot total there was consent, necessity, or b. The physical restraint, if legally sufficient, was lawful- Lawful arrest-then the tort has not been established. 8 - Lawful Arrest/Defendant acting in support of the law Powers of arrest are derived from three sources: a. Arrest with a Warrant b. Arrest at Common Law c. Arrest under Statute In determining whether the physical restraint is wrongful/unlawful or not one must consi der whether the arrest/detention was by: i. A Police Officer or person with statutory authority ii. An Ordinary/Private citizen Cummings v Demas [1950] 10 Trin LR 43. The onus of proof of lawful arrest is on the d efendant. Note that where a statute gives the power of arrest to a police officer or other public off icial,the scope of authority to make that arrest would be governed by the particular statu te (that statute being interpreted strictly). 9