Western Senatorial Aristocracy: Transformation & Survival

advertisement

Papers of the British School at Rome

http://journals.cambridge.org/ROM

Additional services for Papers

of the British School at Rome:

Email alerts: Click here

Subscriptions: Click here

Commercial reprints: Click here

Terms of use : Click here

Transformation and Survival in the Western Senatorial

Aristocracy, c. A.D. 400–700

S. J. B. Barnish

Papers of the British School at Rome / Volume 56 / November 1988, pp 120 - 155

DOI: 10.1017/S0068246200009582, Published online: 09 August 2013

Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0068246200009582

How to cite this article:

S. J. B. Barnish (1988). Transformation and Survival in the Western Senatorial Aristocracy, c. A.D.

400–700. Papers of the British School at Rome, 56, pp 120-155 doi:10.1017/S0068246200009582

Request Permissions : Click here

Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/ROM, IP address: 169.230.243.252 on 23 Apr 2015

TRANSFORMATION AND SURVIVAL IN THE

WESTERN SENATORIAL ARISTOCRACY, c. A.D. 400-700

The last three hundred years in the life of the Roman Senate present us with a

paradox. During much of the fifth century, the institution's strength in Italy was

apparently growing; it increasingly dominated the great civilian offices; in 455-72, it

gave Rome three emperors; from 476-535, it was assiduously patronised by the

barbarian kings, and its families continued the traditions of consular munificence

with devotion. Despite the fragmentation of the empire and disappearance of the

emperor, it seems as vigorous as ever.1 Yet, it notoriously failed to recover from the

Gothic wars as it had from earlier disasters; and, by the time of Gregory the Great, it

was a shadow of its former self. Plague, massacre, grave impoverishment, with the

eclipse of Rome and Ravenna, its social and political centres, in the shadow of

Constantinople, may seem enough to account for this. However, it has been

suggested that so sudden a collapse—a contrast with the social and political

resilience of the Gallo-Roman senators 70 years back—was due to long-standing

weaknesses, social and economic: earlier prosperity was an illusion.2

In this paper, I mean to consider the bases of the Italian senatorial class,

economic, demographic, and in social values, and to compare it with its Gallic

kindred. The demographic part of the problem is twofold: 1. how far was the

aristocratic element in the Roman Senate dominant and self-renewing? 2. How

stable in wealth and numbers were the families from which senators were chiefly

drawn? These questions are related to a third and more basic one: how far were

noble status, high office, and the Senate interdependent?

OFFICE AND THE ARISTOCRACY

As a preliminary, we must establish what the means of senatorial recruitment were.

It has generally been argued that both the Roman and the Constantinopolitan

Senates became increasingly exclusive at this time, until, by c. 450, membership was

restricted to consuls, former consuls, and holders, present and past, of active or

honorary illustris offices of state (the active were 6-8 in number for civilians in the

western empire).3 A. Chastagnol, however, has claimed that the Senate still included

'Cf. Alan Cameron and D. Schauer, 'The Last Consul: Basilius and his Diptych', JRS 72 (1982),

126-45, 138 f., for a positive estimate of senatorial wealth and activity under the Ostrogoths. On the

control of offices and administrative policy by the fifth century nobility, cf., e.g., E. Stein, Histoire du

Bos-Empire I (Bruges, 1959), 337^7, J. F. Matthews, Western Aristocracies and Imperial Court A.D. 364-425

(Oxford, 1975), 357-62.

2

Cf. C. Wickham, Early Mediaeval Italy (London, 1981), 15-19, 27, T. S. Brown, Gentlemen and

Officers [British School at Rome, 1984), chap. 2, esp. 25 ff, P. Brown, Religion and Society in the Age of Saint

Augustine (London, 1972), 232 ff.

3

Cf, e.g., A. H. M.Jones, The Later Roman Empire (Oxford, 1964), 527-32, 540 ff., 545-59. Illustres:

the praetorian prefects of Italy and Gaul, prefect of Rome, magister officiorum, quaestor palatii, comites

sacrarum largilionum, priuatarum and patrimonii. The prefecture of Gaul was in abeyance from 476-50; the

comitivapatrimonii is first attested under Glycerius in 473 (cf. his edict, G. Haenel, Corpus Legum (Leipzig,

1857), 260, also in PL 56, 896 ff.).

TRANSFORMATION AND SURVIVAL

121

all three senatorial ranks, illustrate, spectabilate, and clarissimate, although only

illustres retained the ius sententiae dicendi, and that appointment (conferment of the

laticlavia dignitas, followed by senatorial vote) took place into the clarissimate.4 There

is an interesting ambiguity in the evidence. In 507—12, Armentarius, already a

darissimus, was, with his son, nominated by Theoderic to the Senate, where he would

be able to use his legal eloquence. Only then did they reach the album ordinis. (The

procedure, in my view, is not appointment to any kind oiillustris office, but is related

to the fourth century adlectio to the Senate, though now inter illustres?) By contrast,

Cassiodorus' formulae for creating spectabiles and clarissimi are verbally quite distinct

from hisformula for a senatorial nomination like that of Armentarius, and are given a

greatly inferior place in his collection.6 C. 533, however, the Senate is stated to

contain a. primus ordo and a reliquus senatus, apparently both qualified to vote.7 It may

be, therefore, that full membership was again expanded in the late Ostrogothic

period; or the distinction may be between greater and lesser illustres. Through most

of this era, however, it seems that senatorial membership depended largely, but not

entirely, on a handful of offices.

At the same time, we must notice that basic senatorial status (the clarissimate)

continued to be heritable from clarissimi and spectabiles, as well as illustres, by children

born after their father's promotion, probably for three generations, at least in the

male line; while the two lesser ranks could be reached through a large number of

administrative and other posts, as well as by direct appointment.8 This should have

produced a substantial class of clarissimi, with small hope or ambition of achieving

high office or senatorial membership. Not all clarissimate families will ever have

been connected with the Senate proper; and, for many of those that were, the link

will have been a distant one. A devaluation of senatorial status will have been the

result, and there are signs of this in the late fifth century use of the title darissimus by

leading town councillors of basically curial family.9 This devaluation did not become

marked, however, until the mid sixth century, when the senatorial order was falling

into ruin.10

4

'Sidoine Apollinaire et le Senat de Rome', Ada Ant. Hung. 26 (1978), 57-70, 58-63.

Cassiodorus, Variae III. 33; with Var. IV. 14, formula de his qui referendi sunt in senatu, the procedure

used for Armentarius, contrast VI. 11, formula illustratus vacantis; on adlectio, cf. Jones, op. cit., 541. The

formulae cannot be dated.

6

Var. VII. 37-8; VI. 14; see also Jones n. 16 to p. 530, on Var. VI. 16. 3-4, 12. 4, 15. 2-3, VIII.

17.7.

'Far. IX. 21.5.

e

Cod. Theod. XII. 1. 58, 74, Cod. lust. XII. 1. 11., a. 364, 371, 377, confine status inheritance to

post-promotion children; the last, probably interpolated to fit the post-450 conditions, shows that

clarissimi could still transmit their status; Digest L. 1. 22. 5 shows the generations; cf. Jones, op. cit., 530

and nn. 17, 19; on clarissimate and spectabilate-giving posts, ibid., 547 ff. K. Hopkins and G. Burton in

K. Hopkins, Death and Renewal (Cambridge, 1983), deal at length with the problems of senatorial

membership and status transmission in the early empire.

9

Cf. P. ltd. (ed. J. O. Tjader) 10-11 (a. 489), III. 4—Melminius Cassianus v.c, curial magistrate

of Ravenna; V. 1, V. 5 f.—Fl. Annianus, decemprimus of Syracuse, both v.c. and vir laudabilis. The

Melminii are well attested as a fifth/sixth century Ravenna family, curial, never senatorial in rank.

Compare, perhaps, Avitus, Horn vi, MGHed., p. 110,1. 26 f; but contrast PLREII, Alethius 2, genuine

5

darissimus, and princeps cunae.

10

Cf. P. ltd. 31; F. Deichmann, Felix Ravenna 3. 5 (1951), 23, n.32.

122

S.J. B. BARNISH

How far was noble status in general linked with the clarissimate, and dependent

on the not far distant tenure of high office? T. D. Barnes has argued that families

reached nobilitas by tenure of the ordinary consulship and urban and praetorian

prefectures; perhaps also through the lesser illustris posts. The evidence, however, is

vague and ambiguous." Ancient family counted in its own right: thus, Jerome can

unite achievement and ancestry, speaking of Marcella's 'inlustrem familia, alti

sanguinis decus et stemmata per consules et praefectos praetorio decurrentes'.12 But

even old houses needed to repeat state service to maintain their status. When urging

a friend to take up a career and aim at the consulate, Sidonius Apollinaris pointed

out that otherwise, for all his consular descent, he would 'prove to be that obscure

hard-working type who has less claim to be praised by the censor than to be preyed

upon by the tax assessor'.13 Another friend of senatorial blood was warned that, if

he did not visit Rome and enter the militia Palatina, he would find himself a contemptible rustic, without respect or precedence in the provincial assemblies. By

contrast, the praetorian prefect Arvandus, though of plebeian origin, could win the

sympathetic friendship of political opponents from the nobility, and charge them

with disgracing their prefect fathers.14

There were other qualifications for nobility. For an earlier Gaul, Ausonius, it

could derive from full senatorial race, but also from old aristocratic stock among the

provincial curiae, or from professional attainments which did not necessarily include

the tenure of office.15 In one letter of Cassiodorus, nobilitas is the prerogative of full

senatorial families; but elsewhere, it is the product of ancestral wealth or native

genius, and can be found in the provincial gentry, at least down to spectabilis, and

perhaps to curial level.'6 For Boethius, it is a combination of good birth with

inherited morality, and is not always attached to riches, the key to political success.17

We can only say that there were many nobiles, but some were more noble than others;

that between a Decian consul, and Patricius, the father of St. Augustine, small town

decurion, and definitely a non-noble, there was a large "grey area". This might be

"'Who Were the Nobility of the Roman Empire?'. Phoenix 28 (1974), 444-9, citing Ammianus,

Symmachus, Prudentius and Sidonius. The Gallic evidence is discussed by J. D. Harries, Bishops,

Senators, and their Cities in Southern and Central Gaul, A.D.

407-76 (D. Phil Diss., Oxford, 1981,

unpublished), 41-84 the best and fullest treatment that I know.

l2

Ep. 127. 1.

"Ep. VIII. 8 (tr. W. B. Anderson, Loeb).

14

Assemblies: Ep. I. 6.4. Spectabiles, and probably clarissimi, as well as illustres, were members of the

provincial assemblies, in which the first had the ius sententiae dicendi; cf. Var. VII. 37, Chastagnol, AAH

26, 61. Initially, at least, decurions were members of the Concilium VII Provinciarum, founded in 418, at

Aries; cf. Epistulae Arelatenses Genuinae 8 {MGHEpp. III). Such councils, formal or informal, could play

an important political role; cf. Hydatius, Chron. 163 (Tranoy), Sidonius, Carm. VII. 521-75, Ep. I. 7.

4 f, 10, PVII.7.2, Ennodius 80. 53, 81 (Vogel, MGH). Arvandus: Sidonius, Ep. I. 7; but contrast I. 11.

5, on Paeonius, another parvenu.

15

Prof. Burd. iv. 2, xvi. 9, xiii. 9, xviii. 5, xxii. 21, xxiv. 3 f, xxvi. 3-6, Parentalia'w. 4, ix. 5, xiv. 6, xix.

3, xxx. 2, Epigr. xlv, Gratiarum Actio iv.

"•Var. I. 41, VI. 21.3-4, 23. 1, VII. 2. 3, 37, VIII. 19. 6, 31.8, XII. 24. 3; note also III. 12. 3, VIII.

16.2.

l7

Cons. Phil. II, pr. iv, III, pr. vi; note also III, pr. ii. For the moral dimension of nobilitas, cf.

Valerian of Cimiez, PL 52. 736; and note Edictum Theoderici 59, where nobilitas is left undefined, but is

distinct from mere wealth.

TRANSFORMATION AND SURVIVAL

123

occupied by proud and venerable curial families like those mentioned by Ausonius

or Libanius. It might be occupied by rising professionals like Augustine, for it was

education that united the upper-class grades: Augustine and Ausonius were more

learned than most senators, and this brought them nobilitas, on one criterion. Indeed,

Sidonius feared that it would remain the sole sign of nobilitas, with the abolition or

disuse of official ranks under the Visigoths.18

The grey area will also have been occupied by many of the minor clarissimi

mentioned above. These will often have been barely conscious of their status, unable

to make much use of its privileges, and achieving little of the respect to which they

were entitled. For those, however, who could fairly be called members of the

senatorial class, especially in Italy, the shrunken Senate will long have remained the

focus of their order, of high importance for their self definition. It will also long have

been something of a goal and a role-model for the other inhabitants of the grey area

though ever less so, as access to it became harder. Study of illustris office-holders

should, therefore, yield useful insights into the recruitment and survival of that class,

and into government policies towards it. A variety of sources—laws, inscriptions,

consular diptychs, manuscript titles and subscriptions, papal letters, the Variae of

Cassiodorus, and the private works of Sidonius and Ennodius—give us much

information on high-ranking personnel at this time. From this, I have tried to

approach our first demographic question statistically, dividing the period into six: A,

395^-32, from the death of Theodosius I to the precarious ascendancy established by

Aetius; B, 433-54, dominated by Aetius; C, 456-72, dominated by Ricimer; D,

476-90, the reign of Odoacer; E, 491-526, the reign of Theoderic;19 and F, 527-36,

the post-Theoderican Gothic period. In the main, I have followed PLRE on dates,

careers, and family relationships. There are, however, some important caveats.

Firstly, in A and much of B, senatorial membership was less dependent on

illustris office.20 However, the men and families who reached those offices need not

have been very different, and some investigation of them seems necessary, if only for

comparative purposes. Secondly, D: here our chief source is the Colosseum inscriptions, recording senatorial seat-holders. These are generally dated 476-83; 21 but

Alan Cameron has lately argued that they extend for some years perhaps before, and

certainly after this time, even into the early sixth century.22 For simplicity's sake, I

have followed the usual chronology, which is not so erroneous as seriously to affect

my conclusions. However, attempts to distinguish the state of the Senate under

Odoacer from that under Theoderic, or, like Chastagnol, to calculate its numbers,

are dangerous.23 Thirdly, late Roman nomenclature: saints' names and others of

religious type are increasingly common, and multi-nominate aristocrats are usually

iB

19

Ep. VIII. 3. 2; cf. Ausonius, Prof. Burd. xxvi. 3-6..

I assume that Theoderic effectively controlled Italian appointments after 490, at latest.

20

Cf. Jones, op. cit., 529.

21

Cf. A. Chastagnol, Le Senat Romain sous le Regne d'Odoacre (Bonn, 1966), 28-44. and S. Priuli, in

Epigrafia e Ordine Senatorio I (Titulii, 1982), 575-89. Note that Priuli, 587 f., places a number of clarissimi

in these inscriptions well back in the 4th c. I have not yet found a detailed justification of this theory

and, in any case, it does not directly affect the prosopography of office-holders.

22

JRS 72, 144f.

"His estimate (Le Senat, 47) of 300-600 should probably be reduced.

124

S.J. B. BARNISH

referred to by their final name only.2* These tendencies, the reasons for which will be

discussed later, all too often make the family connections of known individuals a

matter for conjecture, more or less informed, and distinctions between families

rather arbitrary. Nevertheless, I do not believe that the risk of misattribution should

disastrously weaken our overall impressions of the official and senatorial classes. (See

Tables 1-2A.)

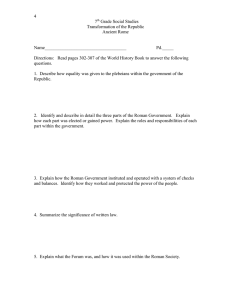

TABLE 1

A

B

11/35 = 31.5% 13/23 = 56.5%

39

17

64

18

5 = 45-5%

7 = 54%

12 = 31%

12 = 70.5%

44 = 68-5%

10 = 55.5%

35 = 54.5% s

15 = 83-5%

29 = 45.5% 2

3=16-5%

1.

2.

3

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

C

6/12 = 50%

7

17

3 = 50%

6 = 8%

13 = 76.5%

13 = 76.5%

4 = 23.5%

D

12/12

16

10

6 = 50%

12 = 75%

6 = 60%

9 = 90%

1 = 10%

E

F

P30/31

4/4

10

3

29

16

18-19 = 58-63 %

4

7 = 70%'

2=66.5%

19 = 65.5%

13 = 81%

23 = 79.5%

9 = 56%

6 = 20.5%

7 = 44%

Key:

1. Non-imperial/royal civilian consuls.

2. Known prefects of Rome.

3. Known civilian illustres with illustris offices not held at Rome, in or outside any of these periods.

4. Consuls as in 1., apparently lacking such offices, in or outside any of these periods.

5. City prefects apparently lacking such offices, in or outside any of these periods.

6. Active civilian illustres, lacking, in or outside any of these periods, both the consulship and the city

prefecture.

7. Active illustres (city prefects excluded) of major Italian or Gallic families.

8. Active illustres (city prefects excluded) very hard or impossible to link with such familes.

Note 1: Artemidorus, city prefect 509-10, had held sub-illustris offices at Ravenna—Var. I. 43.

Note 2: The discrepancy between figures 7-8 for A and B-E may be partly due to a source distortion:

the gradual decline in the fifth century of laws addressed to illustres by a single name, which

often conceals the man's family very effectively. We do better when laws are replaced by

epistolary sources.

Note 3: Appointments made by usurpers are omitted; although these might give a family long-term

status; cf. Sidonius, Ep. III. 12, V. 9, with PLRE II, Apollinaris 1, Rusticus 9.

Since the ordinary consulship (so far as non-imperial civilians were concerned)

and city prefecture were by now almost monopolised by the great families, their role

in the manning of the illustris offices at court is clearly of more interest, and the

similarity of the percentages through much of the period gives some confidence in

the viability of the statistical approach, despite the small size of our samples. From

these figures, it looks as if the aristocracy had acquired administrative dominance by

433, at latest, and perhaps earlier, and had the demographic strength to maintain it

for many years. Yet, it never achieved a monopoly, thanks either to official policy, or

to a shortage of candidates from its ranks. This impression of stability may be

confirmed by examining 'dynastic' successions, in which a consul or illustris was

preceded by an ascendant relative of similar rank. (See Tables 2B-3.)

A high proportion of the major families produced such 'dynasties', and the

24

Cf. Alan Cameron, 'Polyonymy in the Roman Aristocracy', JRS 75 (1985), 164-82.

TRANSFORMATION AND SURVIVAL

125

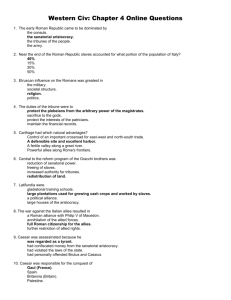

TABLE 2A

Major families in offices of senatorial rank.

A. ANICII, Acilii Glabriones, Auchenii Bassi, Olybrii/Probini, Petronii, Symmachi; ANNII;

ATTICI Nonii; AVITI Mariniani; ? BASILII; DECII Albini; EXUPERANTII; FIRMINI;

?GABINII/RUFII Probiani; GRACCHI; MACROBII; MAGNI/AVITI; MALLII/MANLII;

MEMMII, Aemilii Trygetii, PCaeciliani; MESSALLAE Avieni; PMINERVII (cf. ALETHII);

LIBERII; PALLADII; PETRONII; QUINTILII Laeti Furii; RUFII Volusiani; VENANTII;

ANDROMACHI; NICOMACHI Flaviani; RUTILII.

B. ANICII, Acilii Glabriones, Petronii; BOETHII (PMANLII); CASSIODORI; CORVINI;

DECII Acinatii; FIRMINI; FLORIANI; MEMMII Aemilii Trygetii, Symmachi; PATERII;

PPIERII; RUFII Postumii Festi, Praetextati, Caecinae, POpiliones; TARRUTENII Marciani;

PAUXENTII; PBASSI.

C. ACONII Probiani; CAMILLI; DECII, Basilii; ENNODII; MACROBII; MAGNI; RUFII

Synesii Gennadii; RUSTICII Helpidii Domnuli; MESSII; PSEVERINI; PRAETEXTATI.

D. ANDROMACHI; ANICII Acilii Aginatii; BOETHII; CASSIODORI; CORVINI;

PDYNAMII; DECII Basilii; POPILIONES; PPIERII; RUFII Achilii Maecii, PFesti Agerii,

Sividii, Synesii; PSEVERINI; VALERII Messallae; VENANTII FAUSTI Severini, Glabriones;

MEMMII Aemilii Trygetii, Symmachi.

E. ANICII Acilii Aginantii, Petronii Maximi, Olybriones; BOETHII-SYMMACHI;

CASSIODORI; CORVINI; PCATULINI; DECII Basilii; PFLORIANI; LIBERII; PMAGNI

Felices; RUFII Aproniani Asterii, Petronii; RUSTICII Helpidii Domnuli; PSEVERINI;

VENANTII Opiliones; VOLUSIANI.

F. ANICII Olybriones (Vigilii); CASSIODORI; CORVINI; DECII Basilii; LIBERII; ? House of

ORESTES AND ROMULUS; OPILIONES; RUFII Petronii Nicomachi, PSALVENTII,

PSILVERII.

A: 31 possibly office-holding families in a 37 year period; B: 20 in 22 years; C: 11 in 16 years; D: 19 in 14

years; E: 18 in 36 years; F: 10 in 10 years.

'dynasts' held a large number, though not, save in D (probably a misleading

contrast) the majority of illustris posts. The Decii are the outstanding example of

fertility and office-holding combined: six generations of consuls, and/or high officials,

descended from Aginatius, vicarius Romae in 368-70. 'Dynasties' of two generations

numbered eleven, compared with eight for those over two; in the B, D a,nd E periods,

the numbers of families employed in office seems very similar. It does not seem easy

to distinguish, as Hopkins and Burton do for the earlier empire, between a 'grand

set' and a 'power set' of senators: too many 'grand set' families, producing consuls

and city prefects, also had court illustres to their credit; although some 'power set',

civil service families may have reached the prestige offices at Rome only belatedly

and weakly.25 There does seem, however, to be a marked tendency after A to

"'Grand set' and 'power set': cf. Death and Renewal, 171-5. Examples of senatorial families late or

never in the prestige offices would be the Firmini, Cassiodori, Rusticii Helpidii, Liberii; yet these had

the tastes and connections of the highest nobiles. For obvious reasons, Gauls seldom reached the

consulship or p.u. On the growing 4th-5th c. overlap between court and extra-court careers, see

A. Chastagnol, Tituli 4 (1982), 177, 189.

126

S.J. B. BARNISH

TABLE 2B

Families showing dynastic successions; arrows denote extension into other periods.

A.

ANICII, Olybrii/Probini, Auchenii Bassi, Acilii Glabriones, Symmachi, AVITI Mariniani;

D E C n Albini; PFIRMINI; PMAGNI/AVITI; MESSALLAE Avieni; MEMMII

Aemilii Trygetii; NICOMACHI Flaviani; ?RUTILII; PMANLII/MALLII.

B.

ANICII, Acilii Glabriones, Auchenii Bassi; AVITI Mariniani; BOETHII

( PManlii);

CASSIODORI; CORVINI; DECII Aginatii (Albini); PFIRMINI; PFLORIANI; MEMMII

Aemilii Trygetii, Symmachi; RUFII Postumii Festi, Praetextati, Caecinae.

C.

DECII Basilii (Albini); PMACROBII; MAGNI; PSEVERINI.

D.

ANICII Acilii; BOETHII; CASSIODORI; CORVINI; DECII Basilii; PMAGNI Felices;

MEMMII Aemilii Trygetii, Symmachi; PPIERII; POPILIONES; RUFII Achilii Maecii,

Petronii.

E.

ANICII POlybrii; BOETHII-SYMMACHI; CASSIODORI; DECII Basilii; CORVINI;

•?

PMAGNI Felices; OPILIONES; RUFII Aproniani Asterii, Petronii Nicomachi.

F.

PANICII Olybriones; OPILIONES; DECII Basilii; PRUFII Petronii Nicomachi, CORVINI.

separate court-type and Rome-type illustres. The distinction between military and

civilian illustres is of more obvious importance. A handful of leading soldiers in the

fifth century can be attributed, certainly or conjecturally, to the Gallic, or, less often,

to the Italian aristocracies;26 but only one magister militum, the Catholic barbarian,

Fl. Theodobius Valila, owner of property at Rome and Tivoli, maintained a seat in

26

Gauls: Avitus, Ecdicius, Aegidius, Syagrius, PNepotianus, PMessianus, Arborius, PAgrippinus;

Italians: PLitorius, PPierius, PAemilianus. Aetius, and perhaps Majorian, belong to the fringes of the

Italian nobility; Astyrius and Merobaudes represent that of Spain.

TRANSFORMATION AND SURVIVAL

127

the Colosseum. Another, Sigisvultus, may have founded a senatorial family.27 But,

although, under Theoderic, Goths were appointed to illustris and spectabilis offices,

they seldom seem to have taken up their seats in the Senate;28 and royal propaganda

usually distinguished between Gothic soldiers and Roman civilians.29

Despite this appearance of a strong, self-renewing aristocracy, a further contrast

with the earlier empire, there are signs of weakness. (See Tables 2C—E.)

TABLE 2C

Major families with last known direct official members; those with non-official representatives in later

periods/generations denoted by *.

A.

ANNII; PGRACCHI (but cf. MAECII); ?GABINII/RUFII Probiani (but cf. ACONII

Probiani); FAUSTINI*;

EXUPERANTII;

MACROBII*;

MEMMII

Caeciliani*;

MINERVII/ALETHII*; QUINTILII Laeti Furii*; PALLADII*; RUTILII; ?RUFII

Volusiani*.

B.

? AUXENTII; BASSI Herculii;

TARRUTENII Marciani ?*.

C.

ACONII; MESSII: ENNODII*; CAMILLI*.

FIRMINI*;

PATERII*;

PETRONII

Perpennae;

D. ANDROMACHI: DYNAMII; MEMMII Aemilii Trygetii; RUFII Achilii Sividii, ?Festi Agerii,

Synesii, Valerii Messallae; VENANTII Glabriones, Fausti Severini?*.

E.

ANICII Acilii Aginantii*, Petronii; CATULINI; LIBERII*; ?MAGNI Felices; RUFII

Aproniani Asterii; RUSTICII Helpidii Domnuli ??*; VENANTII ??Opiliones; VOLUSIANI.

F.

CASSIODORI; CORVINI; DECII Basilii; OPILIONES ?*; SEVERINI; SILVERII; RUFII

Petronii Nicomachi.

TABLE 2D

Families which may be those of established nobiles re-emerging into high office.

A.

B.

?AUXENTII; PBASSI Herculii; ?PETRONII Perpennae; ?TARRUTENII Marciani.

C.

PACONII Probiani; PMESSII.

D. PANDROMACHI; PDYNAMII; PLIBERII; PRUFII Valerii Messallae.

E.

PCATULINI; PRUFII Aproniani Asterii; PVOLUSIANI.

F.

PAMPELII; PHOUSE OF ORESTES & ROMULUS (perhaps intermarried with the Corvini);

SILVERII, SALVENTII (PRAETEXTATI).

"For Valila, see PLREII, s.v. The Liber Pontificalis describes Pope Boniface II (530-2) as a Roman,

and son of Sigisbuldus. The general Sigisvultus had Volusianus, bearer of a senatorial name, as his

cancellarius at Ravenna; cf. Constantius, V. Germani 38.

28

Cf. A. H. M.Jones, The Roman Economy (Oxford, 1974), 371 f.

29

Cf, esp. Var. VI. 1, the consul's/0™""'0* VI. 24, VIII. 46.

128

S.J. B. BARNISH

TABLE 2E

Families which may have been new, but were to become well embedded in the senatorial aristocracy.

A.

MANLII/MALLII.

B.

CASSIODORI; ?BOETHII; ??OPILIONES.

C.

?HOUSE OF ROMULUS AND ORESTES; PRUSTICII Helpidii Domnuli; PSEVERINI.

D.

??LIBERII.

E.

?North Italian VIGILII, merging with ANICII Olybrii; ??House OF HONORATUS AND

DECORATUS.

F.

(Avitus, Bergantinus, Clementianus and Fidelis may well represent provincial gentry reaching the

Senate; of these, Clementianus, at least, may have established his house in the residue of the high

aristocracy—cf. Greg. Mag., Reg. Ep. III. 1, X. 6-7.)

TABLE 3

Men with ascendant or descendant relatives in adjoining generations holding active (non-Rome) offices

of senatorial rank (cf. Table 1).

A

B

9 = 82%

7 = 54%

11=28%

3=17-5%

2 = 3%

6 = 33.5%

22/115=19% 11/36 = 30-5%

1.

2.

3.

4.

C

4 = 67%

1 = 14%

4 = 23-5%

7/21=33.5%

D

E

F

10 = 83%

13 = 42-3%

4=100%

6 = 37-5%

3 = 30%

1 = 33%'

5 = 50%

13 = 45%

5 = 31%

13/20 = 65% 21/45 = 47% 9/24 = 37-5%

Key:

1. Consuls;

2. City prefects;

3. Other active illustres;

4. Total of office-holders of this 'dynastic' type.

Note 1: The city prefect Salventius seems to have succeeded or preceded a brother in that office—CIL

VI. 32038.

In all periods, a number of houses dropped out of office-holding, although

many of these continued without known official representatives. While a few families

re-emerged as office-holders to replace them, and a few more may have come to

establish themselves in the high aristocracy, the rate of failure seems the greater.30 In

general too, aristocratic dominance of the administration may be deceptively

impressive. If we take the number of court illustris appointments to be made in each

period, assuming a two-year average tenure of office (perhaps over-generous),31 this

gives the results shown in Table 4.

On this basis, it would seem that some 60-80 per cent of official appointments

30

The tables give the impression that this was particularly so in D. This is probably an illusion, due

to too narrow a date-range for the Colosseum inscriptions. So too the impression that Odoacer made

most use of the great families in relation to his length of reign.

31

Sidonius, Ep. I. 7. 11 suggests that the prae. prae. Gall, held office for less than 3 years. I suspect

that the average, except, perhaps, in E, was less than 2, but we are ill informed on this.

TRANSFORMATION AND SURVIVAL

129

TABLE 4

A

114

44 = 38.5%

1.

2.

B

66

19 = 29%

C

51

17 = 3'10/

> /o

D

45

9 = 200//O

E

105

29 = 27-5%

F

30

10 = 33%

Key:

1. Number of illustris (active, non-Rome) appointments to be made in the period (in E-F, the

praetorian prefecture of Gaul is excluded from these calculations, as Liberius held it throughout its

revival).

2. Appointments certainly or conjecturally made from leading families.

TABLE 5

A

6

B

3

C

3

D

1

E

5

F

2

Number of illustris (active, non-Rome) offices held by an individual who had already held such.

were not made from the high families. Equally, however, only a few of those known

can be called novi homines.32 And, since known high nobiles are far more numerous

than non-nobiles, it is reasonable to assume that the origins of unknown office-holders

should be divided in a similar ratio. On the other hand, high nobiles are likely to be

better represented in two of our prime prosopographical sources, the Colosseum

inscriptions, reflecting Roman residence, and the letters of the well-connected

Ennodius. Furthermore, the average tenure of office seems to have lengthened

considerably over the period (praetorian prefectures are the best evidenced); while

the Ostrogothic rulers seem to have been more willing than their predecessors (in BD) to appoint individuals repeatedly to court illustris offices. This suggests that the

pool of available aristocrats was tending to shrink. (See Table 5.)

Whatever the case, it seems likely that some illustris appointments were being

made from sub-senatorial levels of society, although these cannot be quantified.

Cassiodorus' formula commending candidates (? adlected) for election to the Senate

shows some awareness among the authorities that external replenishment, by the

grafting of new stock, was needed: 'Optamus quidem curiam senatus amplissimi

naturali fecunditate compleri subolemque eius tantum crescere . . . Sed minus

amantis est non amplius aliquid quaerere, unde tantum numerum possit augere'.

Yet, although the 'germen alienum' is inferior in distinction to existing senators, he is

still 'natalium splendore conspicuum'.33 Despite these pious hopes, echoed elsewhere

in the Variae3* few families, as we have noted, moved upwards to permanently lofty

status. One reason may have been the inability, seen earlier, of children to inherit

senatorial rank achieved after their birth. A fair number of new clarissimi will have

been lesser bureaucrats, promoted only after long service, and unlikely to beget

32

See table 1.

Far. VI. 14.

34

Cf. Var. VI. 11, VIII. 19, but contrast I. 41.

33

130

S.J. B. BARNISH

further children. Those who did so will have found it hard to take root in the higher

nobility. Yet, some houses seem to have done so. What, in fact, were their origins,

and how did they achieve their potential for upward mobility?

Ennodius' letters show two possible channels for advancement. While deacon of

Milan, he acted as patron to a string of proteges drawn from the north Italian

aristocracy, many, but, so far as we know, not all with senatorial forbears. These

were usually educated in Deuterius' school of rhetoric at Milan, the 'limen

nobilitatis', which gained a new auditorium. Some then passed on to Rome, where

they pursued their studies under the supervision of leading senators or clergy'

distinguished for their learning; and some followed careers which varied legal

advocacy with government service.35 Only a minority, however, are attested in high

office, and some may have spent all their lifes as lawyers, or as gentlemen of leisure.

Would Arator have reached the comitiva privatarum without the chance which sent

this cultivated ex-advocate on an embassy to Theoderic from the province of

Dalmatia?36 The same combination of public higher education for the provincial

gentry with senatorial patronage is attested for the Sicilians, and may be guessed at

for the young Tuscan poet Maximian, a student at the university of Rome.37

Another road to advancement lay in the actual membership of some great

household, as with the well-born orphaned brothers Castorius and Florus, brought

up by the great Anician senator Faustus Niger; Florus became a distinguished

advocate at Ravenna.38 So too, Arator, another orphan, and perhaps a relative of

Ennodius, was initially looked after by bishop Laurentius of Milan39; while at least

one civil servant of Theoderic had his children educated in the royal palace.40

LOCAL TIES

By such means, the leading aristocrats of Rome might dominate the local aristocracies, and frequently control the careers and activities of provincial illustres.*]

35

Deuterian pupils: Lupicinus, Arator, the son of Eusebius, Partenius, Paterius, Severus, Ambrosius; cf. Ennodius 69, 84—5, 124, 94, 451, 261. Roman recommendations for Partenius, Simplicianus,

Pertinax, Beatus, Fidelis, Marcellus, Georgius, Solatius, Ambrosius—225-8, 368-9, 282, 292, 362, 398,

405-6, 416-17, 424—6, 428, 452. Arator, Ambrosius, Fidelis, and possibly Partenius are attested in high

office. The perhaps Anician illustris Eugenes may have been another pupil of Deuterius; cf. 213.

Simplicianus and Beatus were nobilissimi; Arator a v.c; Paterius and Severus had consular ancestors;

Ambrosius' father was a sublimis; Eusebius a nobilissimus; Lupicinus was nephew of Ennodius, and so of a

major Gallo-Italian family; Fidelis' father was a Milanese advocate of high reputation, but nonsenatorial (Far. VIII. 19. 5f.).

36

Far. VIII. 12.

37

Var. I. 39, IV. 6, Maximian, Eleg. I. 25-44, 59-76 (student life at Rome), III. 47-94 (? family

friendship with Boethius).

38

Ennod. 16.

39

Ennod. 85.

40

Cf. Var. VIII. 21, the children of Cyprian; note also IV. 4, where count Senarius began his

palatine career 'In ipso quippe adulescentiae flore'.

41

J. Sundwall, in his fundamental study Abhandlungen zur Geschichte des Ausgehenden Rb'mertums

(Helsinki, 1919), chap. 3, analysed the politics of much of the Gothic period in terms of tension between

nobiles and novi homines. To me, these considerations seem at least partly to vitiate his very influential

account.

TRANSFORMATION AND SURVIVAL

131

Why, though, did the provincials fail to become integrated with the great families?

Snobbery may be a partial explanation, but it is certainly inadequate, for some did

move up the ladder. We should look rather to Italian 'campanilismo', to the

conflicting claims of Roman society and the home town. These can be amply, if

anecdotally, illustrated. C. 395, bishop Gaudentius of Brescia dedicated his

inaugural sermon to Benivolus, ex magister memoriae, and leader of the local honorati*2

Decoratus (coupled with Florus by Ennodius—were they related?)43 was a native

and benefactor of Spoleto, of noble ancestry, at least by local standards. Not of

senatorial rank, though his ancestors had borne the fasces, as a lawyer, 'praestabat

viribus consularibus se patronum', defended a patrician in a famous case and

eventually became quaestor palatii. He was buried at Spoleto, his fellow-citizens

recording his birth and charities in a fulsome epitaph.44 His brother Honoratus left

him his Roman practice, working as a barrister in Spoleto, despite the venality and

stupidity of provincial courts, but eventually succeeded him as quaestor. Hosius may

have been a similar type: pater urbis of Milan, where he was buried, he was a

patrician, ex comes privatarum, ex comes largitionum, and descendant of a governor of

Venetia and Istria.45 The Cassiodori, who may have come to Italy from the east

early in the fifth century, were firmly rooted in the soil of Bruttium. The writer's

grandfather, though son of an illustris, tribunus et notarius under Aetius, and probable

marriage connection of the Boethian house, preferred Bruttian otium to illustris rank.

His son, illustris minister of Odoacer and Theoderic, used the Bruttian pastures to

supply remounts for the Gothic cavalry. Cassiodorus himself retired to a monastery

on his ancestral estates at Squillace, but not before he had achieved a notable secular

career, and had mingled in literary and religious circles at Rome.46 Again, the

spectabilis Philagrius was a resident native of Syracuse, but spent long at Theoderic's

court, and sent his sons to be educated at Rome, with a royal commendation to a

leading senator.47 Then there is Mallius Theodorus and his descendants. This

learned Christian Platonist and civil servant of Theodosius I and Honorius reached

the consulship in 399. A lawyer by early profession, he was clearly of high education,

but Claudian, who calls him Manlius, says nothing of his birth. We should suppose

him to have belonged to the provincial gentry, possibly of Milan, where he lived,

and which he preferred to Rome.48 His sister or niece Manlia Daedalia was probably

a nun there;49 but later members of the family may not have shared his opinion. His

"Tract, xvi, praef. (CSEL, 8).

13

Ennod. 311, 315—they may have been legal partners.

"Var. V. 3-4, De Rossi, ICUR I. II, p. 113, no. 78; despite the doubts oiPLRE II, the identity of

these Decorati seems highly probable. Decoratus may also have practised at Ravenna (Ennod., above).

For a comparable Spoletan family, see PLRE II, Domitius 4—6.

45

C/L V. 6253. As pater urbis, he may have acted as curator civitatis, an office which would usually

have belonged to a leading decurion; cf. Jones, LRE, 726, 755.

46

Var. I. 3—4, IX. 24—5 Institutiones I, praef., 33. 2 f. The Boethian marriage connection is suggested

by the Ordo Generis; its date by the support which both families gave Aetius.

47

Var. I. 39; cf. IV. 6.

48

Cf. Th. Birt, index nominum to the MGH Claudian, s.v. Manlius and Theodorus.

49

Cf. P. Courcelle, 'Symboles Funeraires du Neo-Platonisme Latin', REA 46 (1944), 65-93, 66-70;

she is described as 'clara genus' in her epitaph.

132

S.J. B. BARNISH

son seems to have reached the prefectures of Italy and Gaul; and, at some point in the

fifth century the house may well have intermarried with the Anician Boethii. The

philosopher (a man of similar tastes to Claudian's consul) and his father shared the

name Manlius/Mallius, not otherwise attested among the Roman aristocracy since

the early fourth century. The former was a correspondent and probable kinsman of

the north Italian Ennodius, and owned property at Milan. This was allegedly in a

run-down condition, neglected by the owner and his agent.50 If this link is correct,

then one leading provincial family had moved its centre of gravity decisively to Rome.

Finally, we might compare Fidelis: his father was a Milanese advocate, famous for his

eloquence, but of no great family; he himself became quaestor palatii under Athalaric,

and a leading figure in the Roman Senate. He played a prominent part in the revolt of

Rome from the Goths, and also in the rebellion of Liguria, where he had much

influence.51 His rise seems similar to that of Theodorus, and, despite his post at

Ravenna, he fixed one foot at Rome and another in his home province.

There were, however, leaders of provincial society who may have eschewed

the excitements of both Rome and Ravenna. In 535, the loyalties of Naples, one

of the greatest Italian cities, were swayed by the rhetoricians Pastor and

Asclepiodotus.52 We know nothing of their families, and they are referred to in no

other context. Tullianus and Deopheron raised a peasant army to fight the Goths

in Lucania and Bruttium. Their father Venantius had probably governed that province, with doubtful honesty, but no illustres or nobiles active at Rome or the court are

attested from that family.53 Correspondingly, a good many Roman senatorial houses

may have avoided both the court and the provinces. The Colosseum inscriptions

give us 34 illustres and spectabiles; but 54 clarissimi, of whom 49 may never have

reached higher rank, and many others whose rank is indeterminate, but will often

have been no higher than clarissimus. Rome and Ostia show some possible examples

of the town-houses of these lesser senators, miniature versions of the great palaces.54

Of these, a large number may have been officials of the second rank who had retired

to Rome;55 but many must have inherited their senatorial status, and some at least

seem to belong to families that had ceased to be concerned in office-holding.56 Was

50

Ennod. 370, 408, 415, 418. Most MS titles and subscriptions give the form Manlius, as does the

consular diptych, but a number have Mallius. Spellings with 'nl' and '11' seem virtually

interchangeable—cf. il(n)lustris, col(n)latio, etc.; Isidore, Etymologiae I. xxxii. 8.

51

Cf. above, n. 35; Procopius, Wars V. xiv. 5, xx. 19 f., VI. xii. 27 f., 34 f. Belisarius made himprae.

prae. Ital.

52

Wars V. viii. 19-41.

"Wars VII. xviii. 20-3, xxii. 20f. VII. xxx. 6, Var. III. 8, 46; we may surmise a successful contest

for local influence with the Cassiodori, who were perhaps too busy outside the province.

54

Cf. Chastagnol, Le Sinat, 47, 74-8. But Priuli (above, n. 21) would redate 37 clarissimi to the 4th c.

If correct, does the resultant number, 17, reflect diminished clarissimus activity, or is it due to epigraphic

chance? For houses, see F. Guidobaldi in Societd Romana e Itnpero Tardoantico II, ed. A. Giardina (Rome —

Bari, 1982), chap. 4.

55

Cf. PLRE II, Valentinianus 3, an ex-silentiary who died at Rome in 519, with the retirement

rank ofillustris.

56

E.g. the Mariniani, Barbari Probiani, Palladii. Note Fl. Messius Phoebus Severus, cos. and/>.a, in

470, under peculiar circumstances. He was clearly a leading noble, but might easily never have held

office. No earlier member of his family is attested in office, or elsewhere, though a grandson may have

been a protege of Ennodius (Damascius, Vita hidori (Zintzen) 11, 94-8, Ennod. 451, PLRE II, Severus

15, 19). The Barbari Probiani and Palladii would be eliminated by Priuli.

TRANSFORMATION AND SURVIVAL

133

this lack of interest, dangerous, in the long run, to their social position, due to the

upper-class ideal of otium? Or was there a promotion bottle-neck, eased by short

tenures of the few illustris offices (less short under the Goths), but compounded by the

grip which a few great families and their provincial clients had on them? We cannot

tell, but it is possible that the Ostrogothic period saw, if not pressure for office from

the hereditary clarissimi, at least pressure for a re-expansion of senatorial membership

without the need for illustris rank.57 It may be that suffragia for the great posts, and

their risks and burdens, were now beyond the means of many potential holders;58

while the lesser palatine offices were too frequently unprofitable, at least during the

crisis years of the fifth century.59 In the fourth century, many senators considered

one or two provincial governorships a sufficient career, and others, though able to

hold them, just preferred to enjoy their incomes in peace.60 In the fifth century these

posts became ever fewer in number, and we have less and less evidence for their

holders.

This evidence had been derived chiefly from the inscriptions set up by grateful

provincials, or by the governors themselves, at Rome or in the provinces, to record

benefactions and patronal relationships. These reflect a strong interest of the

senatorial aristocracy in Africa and southern Italy, especially Campania and

Samnium. c. 400, they virtually dry up.61 Thereafter, most of the illustres seem to be

connected with northern to north-central Italy, the only clear exceptions being the

Symmachi, Cassiodori and Decii; and even the Decii had strong interests in Gaul

and northern Italy.62 (Aristocratic epitaphs and other inscriptions seem rare in the

north before the late fourth century.) Among the growing economic and political

pressures of the fifth century, did the aristocracy tend to leave the southern towns to

their own devices, concentrating, instead, on their northern patronage nexuses,

nearer to the court? Great secular estates still flourished in the fifth/sixth century

south—their prosperity may even have increased—and the urban rich may have

lived in some style.63 Yet, the social base of the gentry may have been weaker, or

more rustic, than in the north. Southern churches built at this time, unlike northern

basilicas, have shown little sign of activity by the lay aristocracy, let alone those

fascinating lists of donors, where a great noble sometimes figures among men and

"See above.

Cf. P. Ital. 48, B14aloan to Agapitus, for suffragium for the prefecture. Var. VI. 10-11, formulae for

the conferment of honorary appointments suggest both lack of money and a preference for otium as

deterrents from active office.

59

Cf. Nov. Val. 7. 3, 22; also, for their attempts to increase profits, 1. 3, 7. 1, 32.

60

Cf. Expositio Totius Mundi et Gentium lv. In period A, 48 governors are, or may conjecturally be,

linked with senatorial families; only 11 reached illustris or consular rank.

61

Cf. B. Ward-Perkins, From Classical Antiquity to the Middle Ages (Oxford, 1984), 22-8.

62

Symmachi and Sicily: cf. Symmachus, Ep. IX. 52; Var. IV. 6. Decii and Campania: cf. CIL X.

6850-1, Var. II. 32-3, J. Moorhead, 'The Decii under Theoderic', Historia 33 (1984), 107-15, HOff;

Decii and Gaul—Sidonius, Ep. I. 9. 2-6, ''Var. II. 3; Decii and northern Italy—Ennod. 58-9, 279, ?230,

75. Note esp. 279, linking the Decian Albinus with four illustres of strongly north Italian connections.

Gelasius, Ep. 41 (Thiel) shows Decian concern for estates in Valeria. Even without the northern weight

of Ennodius' evidence, we would still get this impression of a strong northern orientation among the

nobiles; but even a Faustus Niger might still have patronage links with Sicily—cf. Ennod. 121.

63

Cf. Barnish, PBSR 55 (1987), 157-85, esp. 168-72.

58

134

S.J. B. BARNISH

women of lower, even artisan status.64 Outside Campania there are few of the upper

class epitaphs, senatorial, bureaucratic or curial, which are now frequent and widely

distributed in the north.65 Estates like S. Giovanni di Ruoti and San Vincenzo al

Volturno may have belonged to landlords with small interest in the old urban social

structures of the region, and the Church, in its architectural activity, may have been

moving into a partial vacuum. During the Gothic wars, the aristocracy, both north

and south, wielded important political influence in the provinces. In the south, this

seems to have been exercised primarily among the rural tenantry; in the north, it is

closely linked with the cities—Milan and Verona.66

GALLO-ROMANS AND ITALIANS

The northern nobility differed from the southern, excepting perhaps the Decii, in

another important respect: it formed part of a great arc of senatorial kindred and

patronage which extended from Gaul to Dalmatia, and may have been strengthened

during the turmoils of the fifth century by the movement of refugees and others, such

as Ennodius.67 His family, the Magni Felices, were primarily a major Gallic house,

but they intermarried with the Anician house of Faustus Niger, the Corvini.68 They

were also related to the Firmini, another Gallic house with branches on both sides of

the Alps;69 and perhaps to Liberius, praetorian prefect of Italy and Gaul under the

Ostrogoths.70 Liberius was another connection of Faustus Niger, and may also have

64

Southern churches: cf. C. D. Fonseca, Settimane di Centra di Studio mil'Alto Medioevo 28, 1195 f., C.

D'Angela, Arch. Med. 3 (1976), 475-83, Puglia Paleocristiana III, ed. A. Quacquarelli (Bari, 1979),

207-15 (R. Moreno Cassano), 59f, 68 (M. Cagiano de Azevedo), 163 (D. De Bernardi Ferrero),

412-48 (M. Trinci Cecchelli). Northern mosaic donation inscriptions: cf. Diehl, /Z.CF219a 1864-90, P.

L. Zovatto, Palladia n.s. 15 (1965), 11, M. Mirabella Roberti, Aquileia Mstra 38 (1967), 67ff.,G.

Cuscito, ibid., 44 (1973), 127-66, eund., in Scritti Storici in Memoria di P. L. £ovatto, ed.

A. Tagliaferri (Milan, 1972), 237-58, eund., in G. Cuscito and L. Galli, Parenzo (Milan, 1976), 73 ff.,

80ff.,87. Note also CIL V. 3100, XI. 2089. Rome and environs are excluded.

"Fifth/sixth century southern epitaphs of these ranks: CIL IX. 1378, 2074, X. 1343, ?1346, 1350,

1355, 1535, 1537, 4500, 4502, 4505, 4630; these are mostly from a restricted area of Campania.

Northern: V. 694, ?1658, 3897, 5230, 5414, 5420, 6268, 6398, 6732, XI. ?17O7, 1713, 2585, 7587. From

Ravenna: XI. 308, 310, 313, 316, 317; cf. III. 2659, 9513, 9515-9, 9527, 9532, ?9540, 14239.8, ILCV

250(3), from Salona. Ravenna and Salona are probably atypical because of their administrative

importance. Rome and environs are excluded. Cf. also CIL V. 5415, 6176, XI. 941, epitaphs of

barbarians of senatorial rank in the north.

66

Cf. Procop., Wars VI. xxi. 40ff.,VII. iii. 6ff.,VII. xxii. 2 ff, 20 f.

67

Cf. Rutilius, De Reditu Suo I, 490ff.,541 ff, for Gallic nobles taking refuge in early fifth century

Italy. For ties between north Italy and Dalmatia, cf. above, 7 on Arator. Var. V. 14—15 and IX. 9 give

Severinus, v.i., commissions in Dalmatia; he shares a name with Boethius, and with the Gaul-linked

consul of 461—Sidonius, Ep. I. 11. 10. Note also Harries, 49 f., 218-24.

68

Cf. PLRE II, stemmata 15 and 19, with individual entries; the link with Faustus was probably

through his wife Cynegia, as one of his sons used the name Ennodius. This may connect the author's

family with the Spanish house which rose under Theodosius I. (Matthews, 110 ff, 142ff.).For another

Gallic tie with the Anicii, cf. Venantius Fortunatus, Carm. IV. 5.

69

Cf. stemma 19; on the Firmini, and on Ennodius' house in general, cf. B. Twyman, 'Aetius and

the Aristocracy', Historia 19 (1970), 480-93, 485 ff.

'"Liberius was a frequent correspondent and patron of Ennodius and his relatives, and they shared

the name Felix.

TRANSFORMATION AND SURVIVAL

135

been linked with the Venantii Opiliones, again a family which is likely to have been

represented in both Gaul and northern Italy.71 We can probably trace another

important lineage of African origin, but with similar ties, the Helpidii Domnuli,

functioning in Gaul and at Ravenna and Spoleto.72 In the 550's, the memory of the

noble Ennodius, now a senator in heaven, still linked the leading clergy of northern

Italy with bishop Nicetius of Trier, and so with King Theodebald.73

To these Transalpine links, we should, perhaps relate a good deal in the

political history of the times, and not only in the fifth century, when Gaul was still

part of the empire. Theoderic's intervention against Clovis; his relations with the

Visigoths; the prolonged Ostrogothic revival of the Gallic prefecture under Liberius;

the aid which northern nobiles who had been honoured by the Goths gave to the

Byzantines, following the Gothic evacuation of Provence;74 Frankish rule and

possible coin-minting in northern Italy under Theodebert;75 and the assault on the

Roman nobility by the Lombards at the time when their incursions into Frankish

territory were being resisted by the Gallo-Roman aristocrats Salonius, Sagittarius,

Amatus and Eunius Mummolus:76 all these may be connected with the northern

cousinhood. Negotiations of c. 580, precluding a joint Franco^Byzantine attack on

the Lombards, were handled by, among others, a bishop Ennodius, bishop Laurentius of Milan, and the patricians Italica and Venantius (POpilio).77 To the cousinhood, also, we should perhaps ascribe some of the strength of the Gallo-Romans,

their ability to retain their Roman identity and traditions for many years after the

disappearance of Roman power in Gaul. Is it wholly chance that little fusion with

the Franks seems to have been achieved until the late sixth century, when the

Roman Senate and the Italian aristocracy were so gravely weakened?78

There were, however, other factors at work among the Gallo-Romans, points in

which they resembled, and others in which they differed sharply from their Italian

"Relation to Faustus: Ennod. 429; his link with the Venantii Opiliones (cf. CIL V. 3100 for their

church at Padua) is suggested by the name of his son, Venantius; the presence with him of an Opilio,

v.c.jv.i. at the Council of Orange in 529; and his joint embassy with an Opilio to Byzantium, although

the two men quarrelled. Venantius Opilio, the consul of 524, and probable church builder was also a

friend of Ennodius, and linked with Faustus Niger (Ennod. 150). Note, though, that both Venantius

and Opilio are very common names.

"Cf. PLRE II, Domnulus 1-2, Helpidius 6-7; Helpidius 6 was a frequent correspondent of

Ennodius.

13

Epistulae Austrasiacae {MGH Epp. 3), 5-6; cf. 21.

74

In Ep. Austrasiacae 19, Theodebert refers to a request from Justinian to send 3000 men to help the

patrician Bregantinus, probably Bergantinus, ex com. patr. under Athalaric, and active in the Byzantine

cause (Procop. VI. xxi. 41).

" O n this, see R. Collins in Ideal and Reality in Frankish and Anglo-Saxon Society, ed. P. Wormald

(Oxford, 1983), chap. 1.

76

Cf. Greg. Tur., Lib. Hist. IV. 42, 44, Paulus Diac, Hist. Lang. II. 31 f, III. 1-9. Salonius and

Sagittarius have same names as correspondents of Sidonius; Amatus may be linked with Amatius,

prefect of Gaul in 425; Mummolus son of Peonius with Paeonius, prefect 456-7.

77

Ep. Austr. 25, 38-9, 46; cf. 40-1, Greg. Tur., L. H. X. 2-3. Gregory represents the campaign as a

recovery of Theodebert's empire. Italica and Venantius lived partly in Syracuse, and were friends of

Pope Gregory.

78

Cf. K. Stroheker, Der senatorische Adel im spdtantiken Gallien (Tubingen, 1948), 134 f., attributing

this chronology to the decline of Roman education.

136

S.J. B. BARNISH

kinsmen. Some of these are reflected in the history of the house of Ausonius. His

Parentalia gives us our one detailed picture of an extended upper-class, late Roman

family over several generations, and its study affords useful parallels to the senatorial

demography of Rome. (See Table 6, with comment.)

TABLE 6

1. Number of persons in the Ausonian kindred: 61. (This is a rather arbitrary figure, based on the

family tree in the Loeb Ausonius (ed. H. G. Evelyn-White), I, p. 58, adding some omitted but

inferable spouses, but not their parents, and including Paulinus of Pella's two sons, married

daughter and son-in-law.

2. Number whose age at death is known or roughly guessable: 37. (Note also 3 who died married, but

without more indication of age.)

3. Their average life-span: 42.

4. Number of marriages: 20.

5. Number of childless marriages: ?3.

6. Number of known children: ?41.

7. Average of children per marriage: 21.

8. Average of children per fertile marriage: 2-4.

9. Probable number of male children: 22 (/41 =54%).

9A. Number of named deceased males: 24 (40 = 60%).

10. Numbers apparently dying childless: 18 (/40 = 45%).

11. Number of old/mature maids/bachelors: 6 (/40= 15%).

12. Number of second marriages known: 1.

13. Average male life-span: 47.

14. Average female life-span: 35.

Note first, that the lower chronological limit of the Parentalia distorts these figures—we have very little

information on marriages, and/or children of members of the family mentioned, subsequent to the date

of composition; similarly on their age at death. Second, ages at death are often very conjectural;

R. Etienne, Bordeaux Antique, 367, reviewing the same evidence has more cautiously produced only 14

male and 12 female ages, with average life-spans of 44 and 33-7 years.

It is evident that figures 7 and 8 are very low. Hopkins and Burton {Death and Renewal, 73 f., 95)

suppose that 5-6 births per marriage were needed for a static population. Yet, for two centuries or more

after Ausonius, the Gallo-Roman aristocracy seems to have maintained itself satisfactorily; and so, over

the generations examined here, did the joined houses of Caecilius Argicius Arborius and PJulia. Tracing

the direct line, we find 4 persons in the first generation; 9 in the second; 5 in the third; 6 in the fourth; 11

in the fifth; 3 in the sixth. (Note the caution above, on the evidence for the lower generations.) Counting

the whole tree, with spouses marrying into the family, their parents and known siblings, gives 10 in

generation 1; 20 in 2; 18 in 3; 13 in 4; 14 in 5; 4 in 6; 12 families married into the main line, and all

marriages, where details are known, seem to have been on much the same social level. The estimate of

necessary fertility in Death and Renewal is partly based on its estimate of life-expectancy: 25-30 years for

the senatorial class (70 ff.). This is far lower than my figures 3 and 13-14. Hopkins and Burton use

comparisons with the European aristocracies of the late sixteenth to early eighteenth centuries. But such

nobles, I believe, especially in France, were as likely to be involved in wars as the late republican

nobility, and far more so than that of Ausonian Gaul. Their standards of personal hygiene were

probably also much lower; and, unlike members of Ausonius' family (cf. Par. vi, Pers. iv), their

acquaintance with the arts of medicine is likely to have been small. However, we must allow for

Ausonius' probable omission of cradle deaths (though note Par. x—xi, xxviii—ix, for small children). The

U.N. model life tables used by Hopkins and Burton (72), comparing life expectancy at birth with age of

death may give some help here. With the figures for 30 and 35 years life expectancies (A and B), I shall

compare the received Ausonian family statistics (C); and the alterations made by assuming 6 and 8

unrecorded male cradle deaths (E and D). The figure for known male deaths at which age can be

TRANSFORMATION AND SURVIVAL

137

estimated is 23, in relation to which cradle deaths would be 26 and 35%; revised male life-spans would

be 37-5 and 35, to match the U.N. 35 and 30.

Age

1.

10.

20.

40.

60.

Percentage Surviving Age

A

74-4

58-9

54-1

39-2

19-4

B

77-5

64-6

60-3

46-4

26-3

U.N. FIGURES

C

100

91

70

48

35

D

73

66

52

35-5

26

E

79

73

55

38

27-5

AUSONIAN FIGURES

The figures in columns A and D are, on the whole, fairly comparable; likewise those in B and E a.

fact which inspires some confidence in the use of the Parentalia. However, since the revised male lifespans (above) are less comparable, it does seem as if the Gallo-Roman gentry may have been better at

keeping alive than the U.N. populations compared. Hence, I would infer a life-expectancy of at least

35, and perhaps higher; and, in consequence, would be inclined to reduce Hopkins' and Burton's

estimate of necessary fertility, though some discrepancy with the Ausonian figures would probably still

remain. It is striking that the number of known male children is only two less than the number of known

male deaths; similarly with the females—22:24; 16:18. This is a further indication that the family was

successful in replacing its numbers. Note, however, that rather fewer females seem to have been born

(or perhaps just to have deserved record) than males, and that they probably had a much shorter

average life-span. This will have been a distinct handicap to reproduction. (Cf above.)

Not only does the Ausonian house show a high capacity for self-replacement; its

marriages are consistent with its social standing, made mostly within that class of

educated, landed and established gentry of curial and secondary rank from which it

had originated.79 (In this respect, in its pride of ancestry, and in its fertility, it is very

comparable with the curial families of fourth century Antioch.80) The chance of

imperial patronage made possible a brief rise to a higher level, but this proved

disastrous for Ausonius' grandson, Paulinus of Pella, exposing him to political

intrigue in the upheavals of early fifth century Gaul.81 Only one name in the

Ausonian stemma can be linked with the leading families of Sidonius' Gaul, though

the house may have survived into the mid sixth century.82 These impressions of longterm social and demographic stability correspond well to what we have seen or

surmised in Italy. However, Arvandus and Paeonius are examples of climbing

parvenus in the fifth' century;83 towards the end of the century, the Visigoths were

79

On Ausonius' ancestry and the record of his family, cf. Matthews, 69-87, in some contrast with

K. Hopkins, 'Social Mobility in the Later Roman Empire', CQ,n.s. 11 (1961), 239-49. Note Harries,

48, on possible senatorial descent of Iulianus [Par. XXII).

80

Cf. R. Etienne, Bordeaux Antique (Bordeaux, 1962), 371 f., P. Petit, Libanius et la Vie Munuipale a

Antioche (Paris, 1955), 325—9; these families perhaps show a stronger civic loyalty than do the Gallic,

and their social and economic positions are only very roughly comparable.

"'Paulinus, Euch. 194-219, 290-327.

82

Cf. PLRE II, Hesperius 2; the Auxanius of Sidonius, Ep. 1. 7. 6 f., and Ausanius of Greg. Tur.,

Lib. Hist. III. 36, might be Ausonii.

83

Cf. Sidonius, Ep. I. 7. 11, 11. 5 f., above, n. 76.

138

S.J. B. BARNISH

again appointing Romans to quasi-illustris and spectabilis posts;84 and, c. 600, what

Gregory of Tours calls the senatores were a blend of the old curial and clarissimus

Gallic families with men who had risen through the devious and dangerous channels

of Frankish service. Increasingly, too, these senatores show in their nomenclature signs

of Germanic blood and intermarriage.85 It is very possible that the contemporary

Italian nobility was similarly blending with the Lombards, and with the soldiers and

administrators who had emigrated from the east;86 but, if so, they were rapidly losing

that sense of aristocratic identity which is still strong in Venantius Fortunatus and

Gregory of Tours.

MOBILES AND THE CHURCH

In Gregory's case, at least, this sense was closely connected with aristocratic control of the southern-central Gallic Church, where already in Sidonius' day good

birth had been a major advantage to would-be bishops.87 Italian senatorial families

do not seem to have been so closely involved with the episcopate.88 This is not to say

that they were indifferent to Church politics and administration. In the fifth to sixth

centuries, many Italian bishops, predominantly in the north-centre, bear names

which suggest senatorial blood,89 and Gallic type episcopal dynasties are also

attested.90 On the other hand, we could contrast the episcopal epitaphs in ILCVfrom

Gaul and Italy: of the former, 11 out of 17 mention the deceased's high birth, and, or

secular honours; of the latter, only two out of 57 (those of the Gallic Ennodius, and of

Celsus of Vercelli).91 A supply of well qualified clergy from Africa and the east, less

available in Gaul, may have been partly responsible for this phenomenon;92 but I

suspect that leading Italian families preferred to nominate and manipulate bishops,

rather than to supply them. This process may not always have been successful. In the

Laurentian schism (499-507), the senators and Roman clergy seem, on the whole, to

have favoured the anti-Pope Laurentius, the bishops, especially northern, the

legitimate Symmachus.93 In the context of this struggle, we find the great Liberius in

conflict with a local worthy called Avitus, himself a relative of Faustus Niger, to

secure the election of a new bishop of Aquileia.94 The young deacon Epiphanius was

84

Cf. K. Stroheker, 91. We should note much devaluation of senatorial ranks among the nobiles

addressed by Avitus and Ruricius. Cf. Harries, 54, 'expression not of office but of nostalgia.'

85

Cf. F. Gillard, 'The Senators of Sixth Century Gaul', Speculum 54 (1979), 685-97, below.

86

Cf. T. S. Brown, 107 f, 194 f., though with reservations, esp. in Chap. 9; Wickham 67-72, 74 ff.

87

Cf. Sidonius, Ep. VII. 9. 14, 17 f, 24, IV. 25. 2. See Harries, 27-39, 63-9, for reservations.

88

Cf. Brown, 34 f., 181 ff.

89

Cf. P. Llewellyn, 'The Roman Clergy during the Laurentian Schism', Am. Soc. 8 (1977), 242-75,

256 f.

90

Cf. CIL X. 4163, for Narni; W. H. C. Frend in Latin Literature of the Fourth Century (London, 1974),

ed. J. W. Binns, 123, for Aeclanum and Beneventum.

9

>ILCV 1. 2, chap. 2; ?add bps. Benignus and Senator of Milan—Ennod. 204-5. Note Ennod. 80.

35, Bonosus, priest of Pavia, 'tarn nobilis sanctitate quam sanguine'—and a Gaul.

92

Cf. J. A. Moorhead, The Catholic Episcopate in Ostrogothic Italy (D. Phil. Diss., Liverpool, 1974,

unpublished), 186ff.,on origins. R. Collins, Early Medieval Spain (London, 1983), 98, contrasts the

foreign intake of the Spanish episcopate with the Gallic.

93

Cf. Moorhead, 24-31, eund., 'The Laurentian Schism,' Church Hist. 47 (1978), 125-36.

94

Ennod. 174, 177 f.

TRANSFORMATION AND SURVIVAL

139

groomed by his bishop for succession to the see of Pavia, but his election was secured

by the approval of the eloquent illustris Rusticius of Milan.95 The Cassiodori were

predictably involved in the episcopal politics of Squillace.96 Glycerius initiated his

brief reign by an election law to curb simony, patrocinium, and the creation of

tyrannopolitas bishops.97 The Senate did so again c. 532, 'ab splendore suo cupiens

maculam foedissimae suspicionis abradere'. Interestingly, this consultum was followed

by a royal edict setting a scale of suffragia in cases where papal and other episcopal

elections were appealed to the Ostrogothic court. This measure ensured that only

candidates with money or wealthy backers stood much chance of success.98 In

provincial, if not in papal,99 elections, we may see the senators as serving and using

their clients among the lesser aristocrats in a way which paralleled their secular

patronage. Epiphanius, Rusticius' candidate, was of decent birth, with episcopal

connections, a most skilful orator, and trusted by the gentry of Liguria:100 we could

envisage a worldly career for him which would have led to spectabilis, even illustris

rank, but probably not to a dynasty established among the high nobility.

In Gaul, it may be, its episcopal role gave the aristocracy an alternative, though

inevitably unsatisfactory, focus for its traditions, as links with the Senate became

more tenuous. Sidonius remarks that for a nobility faced with Visigothic takeover,

exile and entry to the Church were alternative solutions.101 It gave them a second

hierarchy to use and reward their educational qualifications.102 It provided control

of devolved, local government; and also, because it was a united body, operating

with provincial councils and archbishoprics, and wielding influence at secular

courts, it helped to unite them, to preserve their sense of identity and political power.

Indeed, we may see it as an equivalent to the lost provincial governorships with the

advantage of more posts and life-long tenure. It also bound the great rural estates to

the towns in which the bishops mainly functioned, so contributing to both the

survival of the city, and of the civitas territory.103 In Italy such a focus was for long

less needed, and the senators exercised only at second-hand a local influence and

control which their Gallic cousins wielded directly. When the Senate as an

institution was so suddenly and drastically weakened in the Gothic wars, they found

themselves lacking a substitute, and with their provincial power-bases undermined.

95

Ennod. 80. 32-9.

Cf. Gelasius, Ep. 38 (Thiel).

"Above, n. 3.

9S

Var. IX. 15-16, on which cf. L. Duchesne, 'La Succession du Pape Felix I V , MAH 3 (1883),

240-66, A. von Harnack, 'Der erste Deutsche Papst und die beiden letzten Dekrete des romischen

Senats', Sitz. Preuss. Akad., 1924, 24-39.

"Much late fifth/sixth century papal politics involved senatorial manipulation. Ennod. 49. 134

suggests actual senatorial candidates for the papacy; and cf. von Harnack, above, PLREII, stemma 25,

of Pope Vigilius; but J. T. Milik, 'La Famiglia di Felice III Papa', Epigraphica 28. 1 (1966), 140 ff.,

indicates one papal dynasty drawn from the lesser nobility.

100

Ennod. 80.7, 53ff.

101

Ep. II. 1.4.

102

Cf. Ep. VII. 9. 24, 'uxor illi de Palladiorum stirpe descendit, qui aut litterarum aut altarium

cathedras cum sui ordinis laude tenuerunt'.

103

Cf. Ep. VII. 15, recalling two priests from their country estates to their town house and duties at

Vienne. On cities and civitates, cf. E.James, The Origins of France (London, 1982), 45-8, esp. Note also

96

R. Van Dam, Leadership and Community in Late Antique Gaul, 153-6,

140

S.J. B. BARNISH

Bishoprics may have had other advantages for the Gallic nobility on which

Italian senators partly missed out: a means of providing for unwanted heirs.

Glycerius condemned the purchasing of bishoprics for unsuitable minors, the wealth

of the diocese being commonly pledged in the process; and Majorian condemned the

compulsory ordination of children as priests with their parents' collusion, and the

consecration of female children as a means of increasing their brothers' inheritance.104 To this 'strategy of heir exclusion' we will return later. Here I shall note

that heirs were still hoped and planned for by the rich—for bishop Gaudentius of

Brescia, c. 400, they went with potentia and divitiae105—yet, partible inheritance had

always been common among the Roman aristocracy. Both through the division of

estates, and the encouragement of low fertility, it may have been responsible for the

rapid turn-over of noble families in the earlier empire.106 The later aristocracy seems

to have been more stable, a contrast perhaps connected with the fourth century

combination of empire-wide office-holding and estate expansion.107 Like its predecessor, however, it was still very liable to the complementary risks of economic and

biological failure; and I would suggest that, in the fifth to sixth century west,

political and economic conditions were making it ever more necessary to ensure the

unity of family property, while legal, social and religious developments were

rendering it harder to do so.

SOCIO-ECONOMIC PRESSURES

Control of the far-flung senatorial estates attested in the Life of Melania will have

been gravely weakened by political fragmentation in the fifth century. Paulinus of

Pella remained the owner of large properties in Epirus, but the rents which reached

him in Aquitaine steadily diminished.108 This effect, though, should not be exaggerated. There are indications that Italian senators under the Ostrogoths still had

interests in the eastern empire, and even in Africa;109 while their relations with Gaul

suggest strongly that land-holding straddled the Alps. It is arguable, furthermore,

that the fifth century tendency to commute taxation in kind to money (adaeratio)

combined with reorganisation and decreases in state demands to produce livelier

trade and more profitable farming in the western Mediterranean.110 On the whole,

104

105

Glycerius, above, n. 3; Majorian, Nov. 11 and 6.

Tract, xiii. 35 (CSEL 68); cf. Jerome, ep. 66. 3, 108; 4-5, E. Patlagean, Pauvrete Economique el

Pauvrete Sociale a Byzance, 152 ff.

l06

Cf. Hopkins, Death and Renewal, 76 ff., 96 ff., P. Garnsey and R. Sailer, The Roman Empire

(London, 1987), 142-5.

107

On this, cf. M. T. W. Arnheim, The Senatorial Aristocracy in the Later Roman Empire (Oxford, 1972),

chaps. 3-4, 6-7. Owing to the separation of military and civilian offices and careers, the nobiles could

now hold power with less risk to themselves and the emperor than in the early empire, a risk which may

formerly have affected their survival (cf. Hopkins, D and R, 166-70, 175, 196).

im

Euch. 270 ff, 408-19, 481 f; cf. Pope Celestine I, in PL 50, 546.

109

Africa: cf. Ennod. 150, for Opilio; the east: cf. Coll. Avellana 228, for Agapitus; Chron. Paschale, I,

p. 623, Dindorf, for Symmachus' house at Constantinople, below, on the eastern marriage of the

Boethii. Wickham, 17, sees the effects of imperial disintegration on private revenues as serious.

"°Cf. Barnish, PBSR 55, 1987, 168-73, 179 f.

TRANSFORMATION AND SURVIVAL

141

though, it is likely that many great families lost much of their wealth, particularly

those with extensive holdings in Africa.