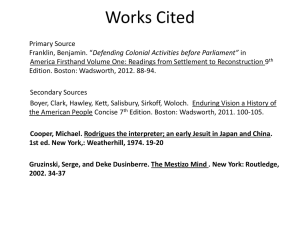

@ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Topics 1. Models of Organizational Stress 2. Stress and Occupations 3. Work Stress and Health 4. Shift Work and Other Work Schedules 5. What Is Burnout? 6. Burnout and Health 7. Burnout Prevention and Treatment @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Topics 6. Time Management 7. Time Management Strategies 11. Job-Related Well-Being 12. Work Stress Organizational Interventions @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning MODELS OF ORGANIZATIONAL STRESS @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Models of Organizational Stress Organizational stress deals with how structure and processes of the organization bring about stress. Job stress is specific to the roles, tasks, and demands of a specific job within the organization. Work stress is generic and applies to all manner of work-related contexts including the stress of informal work, self-employment, a formal job, or work in an organization. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Models of Organizational Stress There are a number of theoretical models of organizational stress. According to Robert Kahn and his associates, stress involves adjustment to work roles. What is a work role? As described by Beehr and Glazer (2005, p. 10), a “work role can be defined as the social character one ‘plays’ in an organization.” @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Organizational Role Stress Three concepts from Kahn, et al. (1964) model: Role conflict occurs when two or more role demands are incompatible with another. Role ambiguity occurs when the duties, responsibilities, and performance expectations of the job are not clearly defined by leaders. Role overload occurs when the workload is too great and there are insufficient resources to complete tasks, an experience referred to as quantitative overload. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Organizational Role Stress (cont’d.) Or the employee does not have the required competencies to complete the tasks even when there is sufficient time, an experience known as qualitative overload. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Person-Environmental Fit Model Stress occurs when there is a poor fit between the worker and the work environment. A worker perceives (subjective) that his or her: Abilities do not match the demands of the organization. His/her needs are not met by the organization. The greater the misfit, the greater the stress. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Job Demands-Control (Job Strain) Model Strain occurs when a worker experiences high psychological job demands and has little control. Low decision latitude refers to having insufficient skills or authority (control) over one’s job to autonomously complete job tasks. The term job strain is used in this model and other organizational stress contexts to refer to harmful consequences that result from exposure to job stressors. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Job Demands-Control (Job Strain) Model There may be: Emotion-related strains (e.g., frustration, anger, and anxiety). Physiological-related strains (e.g., cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or musculoskeletal problems). Job-related strains (e.g., low motivation, low job satisfaction, and absenteeism). @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Job Demands-Control (Job Strain) Model (cont’d.) In this model, the less autonomy and control one has over job stressors, the more strain one experiences. Figure 9.2 Karasek’s Job Demands-Control Model. High demands coupled with low control leads to high job strain. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Effort-Reward Imbalance (ERI) Model The Effort-Reward Imbalance (ERI) Model proposes that high-cost low-gain work efforts are stressful. When we give a lot to our work, we expect reciprocity in the way of high reward. Imbalance in reciprocity causes one to experience distress. This loss of control threatens one’s sense of mastery and self-efficacy, resulting in further stress such as fear of being laid off or being passed over for promotion. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Organizational Injustice Model The Organizational Injustice Model assumes that stress occurs when the organization’s interpersonal transactions, procedures, or outcomes are perceived as unfair. Organizational injustice can occur under a variety of circumstances (employees are not treated with respect and dignity, if workplace procedures are unethical or inconsistent, etc.). This is seen not only as unfair, but as sources of stress as well. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning STRESS AND OCCUPATIONS @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Stress and Occupations Some occupations and jobs appear to be more stressful than others. Police and firefighters: Deal with work of an erratic nature; sometimes boring and sometimes physically dangerous. Show higher rates of divorce and alcoholism than the general public; may reflect job stress. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Stress and Occupations (cont’d.) People-oriented workers (teachers, social workers and health care workers): Generally, experience high stress and a greater likelihood of burnout. Nurses generally report high levels of stress. Physicians report high levels of emotional stress. Physicians have higher rates of divorce, suicide, and abuse of prescription drugs than the general population. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Stress and Occupations (cont’d.) Office workers: Coronary heart disease (CHD) rates are twice as high in women clerical workers than homemakers. Clerical work has high work overload and perceived lack of control. Managers with difficulty coping with stressors are more likely to report high levels of anxiety, depression, and alcohol consumption. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning WORK STRESS AND HEALTH @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Work Stress and Health Work stress, like any form of stress, may affect one’s health and well-being. The most cited and tested model is the job demands-control model. Meta-analysis found that work stress contributes an extra 50% excess to coronary heart disease (CHD) risk. Those who had permanent stress at work were more than twice as likely to experience a myocardial infarction (MI) as their matched controls. There is evidence of a higher morning rise in cortisol among workers with higher work stress. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Work Stress and Health (cont’d.) Negative health behaviours such as poor diet and low physical activity and the metabolic syndrome explained about one-third of the risk of work stress on CHD. Another study found that work stress accelerates coronary artery disease progression in women. Models of work stress help us understand their role in the development of heart disease and MI, but they are not the definitive answer. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning SHIFT WORK AND OTHER WORK SCHEDULES @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Shift Work and Other Work Schedules Working at night disturbs the Circadian rhythm which is the 24-hour biological cycle linked to the light-dark cycle that regulates internal physiological processes (e.g., core body temperature, hormone levels, blood pressure, heart rate, etc.). When this is disturbed, it disrupts our concentration and ability to perform work tasks well. It creates disturbances in sleep and wake cycles. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Shift Work and Other Work Schedules (cont’d.) Shift work is work outside the 7 am – 6 pm frame; 20-25% of workers do shifts. Adverse effects are chronic fatigue, sleep loss, declines in memory and cognitive functioning, family and social life disruptions, and detrimental health conditions. The most prevalent health problems found are those related to the Gastrointestinal (GI) system. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Shift Work and Other Work Schedules (cont’d.) Shift workers often complain about digestive disorders such as disturbances of appetite, irregularity of the bowel movements with prevalent constipation, heartburn, abdominal pains, etc. More serious conditions such as chronic gastritis and peptic ulcers also are more prevalent. This is due to both low-quality food available at night and sleep deficits and disruptions. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Shift Work and Other Work Schedules (cont’d.) Shift work also seems to increase the risk for cardiovascular disease. Shift workers have a 40% higher chance of cardiovascular disease than their day worker counterparts. Working long hours (more than 60 hours a week) and lack of sleep is associated with increased risk of a Myocardial infarction (MI). @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Shift Work and Other Work Schedules (cont’d.) Night workers may also be at increased risk of developing certain forms of cancer (breast cancer and colorectal cancer). Although the exact mechanisms are not known, the most popular hypothesis relates to the hormone melatonin. The pineal gland, a tiny gland in the centre of the brain, releases melatonin during the dark phase and inhibits its release during the light phase of the lightdark circadian cycle. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Shift Work and Other Work Schedules (cont’d.) Melatonin lowers our body temperature and causes drowsiness, which helps us sleep at night. The hormone typically reaches its peak concentration in the middle of the night. However, environmental lighting, such as the lighting in a hospital during the night, inhibits melatonin production. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Shift Work and Other Work Schedules (cont’d.) Melatonin has an inhibiting effect on the production of oestrogen and on the growth and proliferation of cancer cells. Suppression of melatonin through exposure to light during the night-time peak concentration periods likely results in an overall reduced level of blood melatonin levels. The reduced levels of melatonin weaken its ability to suppress oestrogen, which then has an indirect effect on breast cancer risk. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Shift Work and Other Work Schedules (cont’d.) Oestrogen is known to directly stimulate hormone- sensitive tumours in the breast. Some studies indicate that patients with colorectal cancer have lower levels of melatonin. Sleep deprivation among shift workers may lead to immune suppression, which also may contribute to increased risk for cancer. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning WHAT IS BURNOUT? @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning What Is Burnout? Arie Shirom (2011, p. 223), defines burnout “as an affective reaction to ongoing stress whose core content is the gradual depletion over time of individuals’ intrinsic energetic resources, including the components of emotional exhaustion, physical fatigue, and cognitive weariness.” Burnout is a long-term process mediated by our emotional reactions to stress that saps our emotional, physical, and mental energy reserves. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning What Is Burnout? (cont’d.) A worker with opposite characteristics will have vigour, a positive psychological state characterized by emotional energy, physical strength, and cognitive liveliness. Workplace meaningful interactions, challenges, and success are the top three activities positively related to vigour. Maslach’s Burnout Inventory (MBI) originally focused on people-oriented occupations. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning What Is Burnout? (cont’d.) She presents a three-dimensional model of burnout. Emotional exhaustion: the person feels emotionally depleted, drained, and lacking in emotional resources. Two of the major reasons for this exhaustion are work overload or work-related interpersonal conflicts. The specific dimension of emotional exhaustion is being related to declines in work performance. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning What Is Burnout? (cont’d.) This dimension represents the individual stress component of burnout. Cynicism refers to disillusionment, a loss of idealism, negativity, detachment, hostility, and lack of concern. Cynicism represents a way to protect oneself against the overload of emotional exhaustion, to create a buffer of detachment. This dimension represents the interpersonal component of burnout. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning What Is Burnout? (cont’d.) Reduced efficacy refers to feelings of diminished self-efficacy, personal competency, and productivity. These feelings arise from a self-assessment of one’s inadequacy to help others or to be an effective worker. This dimension embodies the self-evaluation component of burnout. Maslach (1998) regards burnout as residing on one end of a continuum with engagement anchoring the other end. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning What Is Burnout? (cont’d.) Engagement represents the positive polarity of her three dimensions and consists of: A state of high energy (rather than exhaustion). Strong involvement (rather than cynicism). A sense of efficacy (rather than a reduced sense of accomplishment). @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning What Is Burnout? (cont’d.) Burnout has some qualities such as fatigue and loss of energy similar to that of depression but is different because it is only associated with work environments. Advanced burnout does not necessarily lead to depression, it could just be cynicism with one’s job and client interactions (development of a dehumanizing outlook toward them). @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning BURNOUT AND HEALTH @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Burnout and Health Vital exhaustion relates to burnout and involves a low energy state, sleep disturbances, extreme fatigue, irritability and feelings of demoralization. Increased risk of CHD, depression, and fatal MI. Burnout measures the constructs of emotional exhaustion, physical fatigue and cognitive weariness. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Burnout and Health (cont’d.) The most common causes of death among the burned-out workers were: Alcohol use related Coronary artery disease Suicide Accidents Lung cancer in men Breast cancer in women. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Burnout and Health (cont’d.) There are evidence that vital exhaustion and burnout are related to coronary risk factors such as: The metabolic syndrome. [The metabolic syndrome includes high blood pressure, high blood sugar, excess body fat around the waist and abnormal cholesterol levels]. Dysregulation of the HPA axis along with sympathetic nervous system activation. Sleep disturbances. Systemic inflammation. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Burnout and Health (cont’d.) Impaired immunity functions. Blood coagulation and fibrinolysis. In fibrinolysis, a fibrin clot, the product of coagulation, is broken down. Poor health behaviours. Burnout is not only a risk for heart disease, but also for other health conditions such as type 2 diabetes and musculoskeletal pain. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning BURNOUT PREVENTION AND TREATMENT @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Burnout Prevention and Treatment Organizational strategies for reducing burnout: Hiring additional employees to reduce work overload. Instituting job orientations and preview programs to prevent burnout in new employees. Give employees realistic and timely job performance feedback. Worker social support groups. Use cognitive restructuring intervention programs. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Burnout Prevention and Treatment (cont’d.) There are some empirical support for the use of cognitive restructuring interventions. Researchers found that cognitive restructuring training that focused on workers looking at their situation differently; examining their expectations, goals and plans as well as learning relaxation skills reduced emotional exhaustion, but not the other two components of burnout (i.e., cynicism and reduced efficacy). @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Burnout Prevention and Treatment (cont’d.) Self-care: each individual takes responsibility for using strategies to minimize burnout. Examples: using humor, quality time with friends and family, engaging in wellness behaviours, taking vacations. Staying current on occupational strategies is also promoted (e.g., attending professional development workshops). Consulting with other professionals on a regular basis (a mentor). @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Burnout Prevention and Treatment (cont’d.) Exercising greater control over one’s work environment when appropriate. Maintaining a healthy balance between work and personal life. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning TIME MANAGEMENT @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Time Management Time management refers to using our time efficiently to accomplish our goals. Effective use of time is a good stress management tool because it reduces the feeling of pressure when we have a backlog of unfinished work or impending deadlines. It improves our productivity and frees time for leisure activities. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Time Management (cont’d.) Types of time wasters: Lack of goals People who do not set goals waste valuable time because they do not know where they are headed. Fear of making the wrong decision or too much stress also can create indecisiveness about which goals to pursue. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Time Management (cont’d.) Too many goals People who have too many goals become quickly overloaded. They may experience concentration difficulties or physical fatigue as the worries and pressures of unfinished tasks mount. Procrastination Procrastinators view certain tasks as aversive and try to avoid them as long as possible. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Time Management (cont’d.) As a result, they waste valuable time until their deadline is about to approach and then rush to complete the task at the last minute. Some enjoy the thrill of their brinkmanship, the adrenalin rush of living on the edge. Others simply are unable to self-motivate until the anxiety of their impending deadline becomes intolerable. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Time Management (cont’d.) Procrastinators may avoid dealing with unwanted or unpleasant tasks by using distraction, daydreaming, wishful thinking, etc. to kill time so that there is insufficient time left to work on the avoided task. They then can rationalize that they will do the task tomorrow. Perfectionism Perfectionists often become immersed in trivial detail and lose sight of the big picture. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Time Management (cont’d.) They waste a great deal of time on minor tasks instead of allocating their time proportionally to ensure that major tasks receive the lion’s share of their time. They also may engage in endless cycles of repetitive checking and rechecking of their work product in pursuit of perfection. Work interruption Interruptions, whether they are phone calls or dropins, can consume a lot of your time. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Time Wasters TIME MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Time Management Strategies Some limited research that demonstrates time management training results in enhanced perception of the control of time, greater job satisfaction, and less job-related somatic tension. Popular time management strategies: Keep a daily time log The idea is to record information about how you use your time. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Time Management Strategies (cont’d.) This raises your awareness of particular times or situations where you are wasting time or could be working in a way that uses time more efficiently. Establish goals and prioritize Use a “To-Do List.” On the list record all the tasks that you need to do. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Time Management Strategies (cont’d.) Large or complex tasks should be broken down into smaller tasks that are also listed. Then prioritize your tasks using an A, B, C goal system. “A” goals are top priority goals that have important positive or negative consequences associated with their completion. B” goals are important, though second to “A” goals. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Time Management Strategies (cont’d.) Finally, “C” goals are given the lowest priority. This is a rolling list so task items that are completed are deleted, and new tasks are added as they arise. Follow the Pareto principle The principle that only 20% of one’s goals contain 80% of the total value; therefore, good time management involves spending most of one’s time on the most important 20% of one’s goals. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Time Management Strategies (cont’d.) Prune and weed File or throw away paper when it crosses your desk rather than letting it pile up. Archive or delete already-read e-mail messages that are filling your inbox. The idea is to process paper or electronic information once rather than repeatedly. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Time Management Strategies (cont’d.) Set boundaries to manage your physical workspace and technostress Closing your office door sends an implicit message that you are busy and not to be interrupted unless it is important. Reply to e-mails, text, or phone messages at scheduled times each day rather than throughout the day (e.g., once in the morning and once in the late afternoon). @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Time Management Strategies (cont’d.) Turn off your cell phone during periods when you are working on a task and wish not to be interrupted. Take time out from focusing on digital media to prevent digital overload. Delegate when feasible and appropriate. Delegating lower priority tasks enables you to focus more of your time and energy on “A” priority tasks. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Time Management Strategies (cont’d.) Many who are reluctant to delegate are perfectionists who believe that if they do not do it themselves, it will not be done correctly. Schedule relaxation time Scheduling relaxation time to recharge your batteries seems counterintuitive to some (e.g., Type A personalities). However, the idea is to work more efficiently rather than to just work harder. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Time Management Strategies JOB-RELATED WELL-BEING @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Job-Related Well-Being Two reasonable goals for obtaining job satisfaction are to manage job stress well and strive for jobrelated well-being. We are most likely to experience flow when we work on tasks that challenge us while at the same time, we feel some sense of mastery over them. The addition of positive thoughts and feelings is required for job satisfaction. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Job-Related Well-Being (cont’d.) The Self-determination theory states that when we are intrinsically motivated to move toward realistic goals we choose, we have a greater chance of experiencing well-being. A job is more likely to foster well-being if there is flow, we develop meaningful relationships with community and employees, and we move forward with goals. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Job-Related Well-Being (cont’d.) In sum: A job is more likely to foster well-being if it supports: our ability to experience flow, pursue intrinsically motivating goals that we have some say in choosing, develop and maintain positive connections with other employees when working on our goals, and experience a good rate of forward progress toward achieving our goals. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Job-Related Well-Being (cont’d.) Elements of the job environment that determine well-being: Opportunity for personal control Aspects of previously discussed self-determination theory such as autonomy, freedom of choice, and the ability to make decisions about how to conduct one’s work. Opportunity for skill use The ability to use one’s skills and talents in the job relates to the experience of competence. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Job-Related Well-Being (cont’d.) Externally generated goals Goals presented by others (e.g., organizational leaders) should be reasonable so that we do not experience quantitative or qualitative job overload. They should be communicated clearly to avoid creating role conflicts. And there should be sufficient resources to accommodate the job demands. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Job-Related Well-Being (cont’d.) Variety Varying routines and changing the nature of work tasks help to prevent boredom. This also introduces new challenges that can foster the development of new skills and promote the experience of flow. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Job-Related Well-Being (cont’d.) Environmental clarity Timely and accurate feedback about worker performance and communication about the consequences of satisfactory and unsatisfactory work behaviour help to reduce ambiguity. Clarity about the future security of the job reduces uncertainty. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Job-Related Well-Being (cont’d.) Availability of money Salary and overall income play a role in overall job satisfaction. Workers tend to use a social comparison process of comparing their pay with other workers’ pay in the same job category. If they believe their pay is less than others’ pay with similar experience working the same job, they are more likely to be dissatisfied. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Job-Related Well-Being (cont’d.) Physical security If a worker feels endangered because of unsafe working conditions, he or she is more likely to be dissatisfied. Environmental physical stressors such as excessive heat or noise also can reduce satisfaction. A comfortable, safe, and ergonomically healthy work environment is optimal. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Job-Related Well-Being (cont’d.) Supportive supervision Effective leadership and supportive management can create work environments that are more positive and conducive to employees satisfactorily fulfilling work goals. Opportunity for interpersonal contact The opportunity to have satisfactory social relationships at work is important. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Job-Related Well-Being (cont’d.) Co-workers provide many of the social rewards (e.g., validation, social support). If there is frequent interpersonal conflict, then social rewards are diminished, and employees are less likely to be satisfied. Valued social position Having a job that has meaning to the worker is important. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Job-Related Well-Being (cont’d.) The job’s status or the prestige of the occupation also can play a role in job satisfaction. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning WORK STRESS ORGANIZATIONAL INTERACTIONS @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Work Stress Organizational Interactions Organizational work stress interventions aim at the employee directly or the organization itself and may be either preventive or recovery oriented. Primary prevention strategies: minimize the source of stress and promote a supportive organizational culture. Stress audits are used to identify problem areas. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Work Stress Organizational Interactions (cont’d.) Then resources are directed to these areas to make positive changes such as changing personnel policies, improving communication systems, redesigning jobs, or allowing more decision making and autonomy at lower levels. There is generally good evidence for their effectiveness in reducing objective measures of stress (e.g., blood pressure, sick days taken). @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Work Stress Organizational Interactions (cont’d.) Secondary prevention: teaching stress management skills. This educational approach is usually multimodal and includes training in relaxation, time management, assertiveness, lifestyle management, or any one of a host of traditional stress management skills. These skills usually are taught to groups of employees at the work site. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Work Stress Organizational Interactions (cont’d.) There is considerable evidence to suggest that any measured benefits decay rapidly over time and are rarely maintained beyond 6 months post-training. Tertiary prevention: employees need rehabilitation and recovery assistance due to mental or physical health conditions related to stress. The Employee Assistance Program (EAP) is an example. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Work Stress Organizational Interactions (cont’d.) The Employee Assistance Program (EAP) is a program that provides “counselling, information, and/or referral to appropriate internal or external counselling treatment and support services for troubled employees”. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning (cont’d.) Table 9.2 Primary, secondary, and tertiary workplace stress management interventions. The End…. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Summary Job demands-control model states that stress results from a worker experiencing high psychological job demands and low control. Certain occupations and jobs are stressful. Shift work can result in GI problems and some types of cancer. Burnout is the gradual depletion of personal energy. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning Summary (cont’d.) Work environment that supports well-being should allow for autonomy, work variety, and more. Time management strategies can reduce stress and burnout. Organizational work stress interventions include primary, secondary, or tertiary prevention strategies. @ 2012 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning