Uploaded by

yxveratang

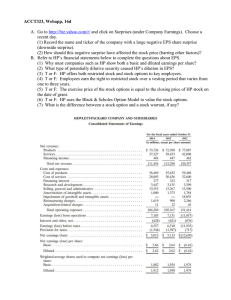

Share Repurchases & Firm Outcomes: A Financial Economics Analysis

advertisement