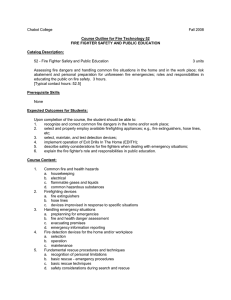

WEIGHT-CUT: SYSTEMATIC STRATEGIES Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Weight-Cuts - Overview and Current Practices 3 Chapter 2: Assessment - The Cut Starts Here 5 Chapter 3: Data Acquisition 11 Chapter 4: Camp Management 18 Chapter 5: Cut/Fight Week 33 Chapter 6: Rehydration and Refuel 42 Chapter 7: Tying it all together 50 About the Authors 51 Action Tools – Checklists References 56-61 62 The Goal of This eBook As professional strength coaches, a major priority in every camp is to make sure we are preparing a fighter with an increased capacity to enhance their skills, elevate their physical conditioning, and even improve cognitive capacity. However, we are also highly involved with making sure our fighters come to the scale at the predetermined weight for their divisions. With this book, we are striving to share a set of systematic strategies that may help optimize a weight-cut. Not to mention, impart ideas on the process of refueling and rehydration. By using science, experience, and rationale decision-making, we will share strategies that can assist strength and conditioning coaches, skill coaches, nutritionists, as well as new weight-cut coaches, to maximize a fighter’s performance through camp, the weight-cut, walk up to the scale, and through the fight. This book’s sole purpose is to be an open exchange of ideas, translation of the applicable science, and to advance the field of fight performance training. To quote fellow coach -- and best-selling author -- Brett Bartholomew, “A coach’s work should strive to stimulate further discussion, spread the ideas that are the result of shared experiences, and do so in a way that’s positive, pragmatic and inclusive.” That is the mission of Weight-Cut Systematic Strategies. Phil Daru with UFC's Dustin Poirier Ricci with Bellator light heavyweight Liam McGeary Introduction Firstly, thank you for taking the time to go through our book on weight-cuts. It is important to clarify immediately that this book is for weight-cuts at the professional level in which fighters will weigh-in a day prior to competition and have a minimum window of approximately 24 to 30 hours to refuel and rehydrate. The science and art of competing in Jiu-Jitsu tournaments with same day weigh-ins, or same day weigh-ins replicated weekly over many months (such as in Wrestling), differs greatly from the book’s specific focus on several pre-day weigh-ins during a given year. With that in mind, Daru and Ricci will address same-day weigh-ins in a separate book later. We have designed this book for coaches, nutritionists and fighters that are entering fight sports and wish to learn a framework of knowledge. If you have extensive experience in this field and a thorough science background, this book will be a review for you. The topic of weight-cuts, for those of us closely tied to weight-class sports, is highly debated, highly volatile, and certainly not supported through extensive research (as far as best practices). By no means are we claiming that the science, strategies, methods, and in some cases, best predictions, addressed in this book are the sole path to safe and effective weight-cutting. Moreover, you will see the following words used often in this book: may, could, should, would, and possibly. This is because of the inexact nature of weight-cutting. However, we are confident we will be sharing viable ways to navigate through the process, as to remove the complete arbitrary nature of weight-cuts. And this remains a priority as many fighters continue to go from unreasonable weights in camp, into rapidly reduced bodyweights, and highly impaired fighters once they reach their goal weight. If they reach it at all! Through our shared experiences in the industry, we have learned much about human physiology and body composition. This is what we are trying to manage effectively as the fighter goes from camp to the scale. We can do this by gathering initial data, such as weight-cut history, body fat percentage, lean mass, and total body water. All while closely monitoring training volumes, approximating daily caloric expenditure, developing dietary and fluid requirements, and watchfully recording sleep durations and quality. Fortunately, the practicality and financial commitment toward monitoring the aforementioned variables is far more feasible than years ago. If you are highly committed to fight sports and plan to undertake the process of weight-cutting, we do recommend purchasing a reliable body fat tool that will provide you with the proper measures such as body fat percent, lean mass, and total body water (TBW). These three markers are going to be vital in determining how, and if, the fighter can arrive at scale weight. Additionally, a refractometer for measuring hydration/specific gravity through camp is quite cost effective and helpful. [1] In addition, if you are fortunate enough not to be in New York, obtaining biomarkers (blood work) is not difficult and can provide excellent information to help monitor the fighter’s physiological status through camp. We also include tools by Polar, that measure HR, Blood Pressure, estimated caloric expenditure, and overview sleep patterns. Plus, we are now implementing MuscleSounds Technology which can assess skeletal muscle glycogen status. These tools aren’t infallible and only provide guidance in the decision making so effective cutting practices are not contingent upon the tools and markers discussed in this book. We worked hard on this book with the purpose of delivering information that facilitates your own approach to an effective weight-cutting program. In essence, this is a book which shares the way we can think through this vital process, and how we do our best to get the fighter to the cage, ring, or mat; not just safely, but also with the capacity to perform at their optimal physical and mental ability. Coach Daru with one of MMA’s fiercest champions, Joanna Jedzrejczyk [2] Chapter 1: Weight-Cuts - Overview and Current Practices If you have been involved in fight-sports at a variety of levels, you have certainly observed radical weight cuts. It is also likely that you have seen mishaps, fighters being helped to the scale, fighters taking one foot off the scale, Epsom salt baths, bizarre dietary practices, debates to change the process, new proposed rules, constantly changing rules, organizations with different rules, the media’s fatalistic hyperbole regarding weight-cuts, and a number of other crazy happenings. Accordingly, we accept that much of the alarm with the current practices is warranted. Some believe the issues are solved by a fighter staying in fight-shape year-round; for example by walking around at a bodyweight three to four percent greater than that of their scale weight. It is reasonable thinking. However, it is not easy, and not likely to hold as the customary approach in fight-sports until the sanctioning bodies in MMA, Boxing, and so forth, decide there is a way to change this while assuring it does not completely upend current weight-classes, threaten key matchups, or compromise revenue. Additionally, if an overhaul is instituted it will likely need to be done over time, and for a new roster of incoming fighters. The California State Athletic Commission (CSAC), and their 10-point-plan, has suggested a capped weight gain between fights at 10 percent above the scale weight. This is a feasible number, as we set the maximum in this book at about12 percent. ONE Fighting Championship (ONEFC), based out of Singapore, has a novel approach worth reviewing and it may influence current practices and guidelines globally. Yet currently, rules still may vary from state to state in the US, differ in Europe from Brazil, or may vary in other countries that sanction combat sports, which all further obfuscates weight-cutting. A clear change is the increase in the refueling and rehydration window for weigh-ins in the UFC and Bellator. They now allow fighters to weigh-in as early as 9:00 am the day before an event. This may provide a fighter with as many as 36-38 hours of rehydration and refueling. Which, is a duration, when done right, that can positively and significantly change physiology for fight prep. Yet, with knowledge of this some fighters now believe they may be able to lose greater amounts of weight and rapidly pull more water. Consequently, with every measure taken in weight-cut practice there may be an associated challenge or risk. So the question remains, can weight-cuts be done safely at all? It is reasonable to assume that our ancestors survived through unintentional weight-cuts, or certainly natural undulations in weight and body fat percentages as food acquisition was contingent upon a host of volatile variables, none of which included vending machines, ordering pizza, driving to Whole Foods, or grabbing a bag of chips. Yet, we do have evidence with athletes that have practiced years of extreme and/or sustained weight-cuts, in which metabolic disruption/adaptation may be a real consequence. Furthermore, in rare cases we have seen the greatest preventable tragedy in weight-cuts: death. [3] Accordingly, we will not downplay the dangers associated with unhealthy weight-cutting practices; particularly when a fighter is called on two weeks’ notice for a shot at the belt; and we are not advocating any of the current practices or rules. What we are suggesting, is strategically navigating through the current system. As experienced professionals in this field, we have witnessed reasonable dietary and training practices throughout the year make a major difference in the athlete’s propensity to reach the scale. We will share practices such as putting an off-camp maximum weight (in the range of 10 to 12 percent above scale weight), acquiring the proper information at camps start, and monitoring all the variables we will address, which ensure a fighter can achieve a maximum of three or four effective weight-cuts throughout the year. In our view, the cut starts the moment the fight date is set. With that in mind, formulating strategies which help fighters reach the scale, while concurrently increasing skill acquisition and all biomotor abilities is a top priority in any weight-cut process, and this task is what we hope to translate in this book. So, let’s start this process! Ricci with UFC heavyweight Stipe Miocic, coaching legend Ray Longo, UFC fighter Gian Villante and LAW wrestling academy coach Jaime Franco [4] Chapter 2: Assessment - The Cut Starts Here The assessment of a fighter prior to camp is crucial! Much of how successful a fighter may be in their cut, or perhaps potential difficulties they may encounter in their cut, are contingent upon scores of factors. As a result, we first strive to acquire historical context so we can better understand the physiology, customary practices, and the psychological component of the fighter’s weight-cutting experiences. Reason tells us that a 24-year-old Division I All-American Wrestler, transitioning into MMA, will have had completely different weight-cut practices than a 22-yearold Muay Thai champion looking to make an MMA debut after a year of ground work. Their metabolisms and physiology may be completely different because of their weight-cut strategies, cut frequencies, and practices, leading up to the point in which they come to you. In general, their body types may be distinctly different as striking arts may attract those with different athletic and anatomical structures than let’s say Judo, Jiu Jitsu or Wrestling. Therefore, let’s talk about some of the information we gather in the assessment, its relevance to your fighters cut, and the physiology we may potentially need to navigate as a result. 1) Weight Cut History – It is vital to establish if your fighter is a Wrestler with many years of sustained weight-cutting, or a Kickboxer that cut only several times a year, as examples. This may provide insight into the type of cuts your fighter has undergone, and how long and how often they were forced to perform under caloric restriction. Same day weigh-ins with Wrestlers, Jiu Jitsu practitioners, or fighters at amateur levels, as a long-term practice is tough on the metabolism and physiology. It is imperative to have some context on your fighter’s cut history. Along with potentially affecting metabolism, historical practices influence what they perceive a weight-cut to be, and what their coaches have done traditionally to make weight. Conversely, maybe you are working with a fighter that has never cut before, which proposes different challenges. Either way, the variables in this chapter are in essence all part of weight-cut history, and all are highly influential in what may have driven previous cutting success, or what may have gone completely wrong in past cuts, and what you may need to do to redirect and/or improve this process. 2) Scale Weight and Class – It is of course imperative to know in advance a fighter’s weight class aspirations and determine the feasibility. Often young fighters come in with unrealistic projections of a class, or with recommendation from a coach that needs a 155pound MMA fighter on their roster. Despite the fighter currently being a lean 190 pounds. In the Data Acquisition section, we highlight the numbers that help us determine the viability of the fighter’s desired class. Here, we must establish if they have made this weight before, and if so, when was the last time they did, and what have they done since they last made weight? Did they make 155 pounds in January, and it is now July and they have done little to sustain a reasonable weight and remain in respectable condition? It may be surprising, but some fighters don’t train intensely between fights, or eat very well- at all! [5] Such factors are going to have a significant role on how we design the weight-cut, when it starts, and if they can perform well at this class. Obviously, it is not just a question of “Can we make the weight?” Somehow, most fighters always seem to get to their designated weights despite their condition between fights. But because they’re tough any associated degradation in performance may not be easily visible or measured. Nonetheless, this is about improving weight-cuts over time, not simply surviving them. 3) Max Weight – This is a vital piece of information directly tied to the fighter’s history and weight class aspirations. Assuming you are working with a fighter for the first time, and they have an extensive weight-cut history as a light heavyweight (205 pounds) MMA fighter, we want to gather as much data as we can about their previous weight-cut history prior to fighting, and how they practiced cutting since becoming a fighter. It is important to know exactly how many times they have made the cut to 205 pounds, as well as learning the maximum weight they have been beyond 205 pounds; and ascertain if they always rise to that level. Accumulating this data is key, because if that 205-pound fighter has a habit of an accelerated weight gain of water and fat storage up to 240 to 245 pounds post fight, you may be dealing with a suboptimal metabolism because of such habits. This may mean we have an athlete very susceptible to fat gain, and one who has greater difficulty pulling (or removing) fat. Consequently, this may also make them vulnerable to greater than desired loss of lean mass during camp and the weight-cut as they must drop weight fast. Accordingly, this fighter will require a cut that starts well in advance of camp if you’re fortunate to be working with them long before the fight date. They will likely require careful dietary practices, including strategically designed caloric and macronutrient intakes. You may even need to incorporate low-intensity cardio (often maligned) well before camp starts to get body fat to a camp ready level. Our point is you may often be starting with less than optimal metabolic and hormonal physiology. This, resulting from years of radically applied weight-cuts and then rapid weight gain. Accordingly, this will require serious brain-storming and strategy to help correct. Correcting a metabolism that has undergone adaptive thermogenesis takes a lot of work, and it’s a topic Daru, Ricci and the Fight Science Institute are addressing in separate works. However, if your fortunate and working with a fighter that has remained within reasonable range from fight to fight, let’s say an MMA lightweight of 155-pounds,whom holds 10 to 11 percent above scale weight between fights, equating to approximately 170 to 172 pounds, you will be in solid cut position. This is why we try (and we reiterate try), to keep our fighters within a maximum cap percentage of 10 to 12 percent above scale weight between fights; as opposed to our light heavyweight that gorged up to 240, which is nearly 20 percent above scale weight. [6] 4) Age – So far we are addressing subjects that seem obvious, but we are trying to make a checklist of all variables to consider when planning weight-cut strategies. At a given point in a fighter's career, all the variables discussed might, or might not, significantly affect your fighters cut. However, this does not mean we shouldn’t take counsel of each variable along the way as to be cognizant of all potential factors that may influence a weight-cut. We understand physiology can change significantly as one ages - even with an athlete. Often fighters who easily made 145 pounds at the age of 22, fail to calculate how the years of training and cuts may have significantly changed their bodies now that they are age 30. Natural occurrences with age are things such as slower fat burning and altered metabolism, different hormonal profiles, and for many athletes increases in muscle and bone densities, which add weight. These are a few factors that may make future cuts to that same class extremely difficult, or not worth the physiological and psychological degradation associated with once again cutting weight down to that class. It is wise to consider that the cut for the aging fighter may need to be more methodical, and likely require more time from max weight to the scale. Additionally, is not out of the realm of possibility that the fighters training schedule, intensity, and sparring may not be consistent with their camps from five or six years ago. There are often aggregated injuries which may limit their sparring, or options for conditioning the cardio-respiratory system, for instance. As a result, they have diminished total training volumes from the previous camps and are not expending as much energy toward the cut. This will mean stricter adherence to dietary practice, closely monitoring total caloric intake, protein intake, and macronutrient distributions to make the cut successful. Since they may not be able to eat or train the same to cut the weight as when they were younger, we must adjust. Therefore, it is imperative we have knowledge of their current training schedule and the volume and intensity of training, so we can make sure food and fluids can coincide accordingly. Why, as the Nutritionist, Weight-Cut Specialist or S&C coach, should we be cognizant of all this? Since fighters often rely on what has historically worked they are not always aware of their own physiological changes or the decline (justifiably) in their total camp volume and intensity, as they have aged. Some remain confused, or discouraged, as to why and how all of this may be making the cut more difficult than it was when they were 23-yearsold. Consequently, we may have to do much of this thinking either for them, or with them and their team. That’s a vital function in our job. Perhaps the greatest variable that may change with age is – recovery! This doesn’t just mean recovery during camp, but also during perhaps the most crucial process of a successful weight-cut, the rehydration and refueling. This is why the cut must be less drastic and more methodical. [7] As our fighter ages, their ability to rebound from dropping 20-pounds of water, some fat, a bit of muscle, a bunch of glycogen, and electrolytes in a 24 hour period, and then properly redistributing and replenishing all of this from scale to the fight, may be less efficient now, potentially-much less! Hence, just like an NFL quarterback, or MLB pitcher, who reinvent themselves as they age due to a decline in their physical abilities, we have to consider that adjustments may be necessary for successful cutting as our fighters age. 5) Gender – Fortunately, gender is an important issue in fighting today as women now fight in the UFC, Bellator, Glory and so forth. They are excelling as martial artists and have ever-increasing fan bases. As we progress through the book, be mindful that there are major differences in female physiology well beyond what we address here. At the forefront, generally, total body fat percent is higher in a female; total lean mass as a percent of total body mass is lower, resulting in a significantly lower percent of total body water, all making for a tougher cut. Commonly, you will find a female athlete/fighter in the range of 53 to 58 percent total body water, as opposed to 62 to 70 percent in males. Female body fat percentages may range from 13 to 20 percent toward a camp’s end, but currently we have little data specific to female fight sports. Nevertheless, this proposes several considerations for a female fighter and their cut. First, because of the propensity to hold higher levels of body fat, we may want to consider having a lower maximum bodyweight percentage above their scale weight than that which we proposed for men. This may be in the range of 8 to 10 percent above their scale weight. And because women will need to rely on cutting larger amounts of fat as a percentage of bodyweight, they will require a slower and more consistent weight-cut. With that in mind, your female 125-pound fighter may want to max at about 136 pounds between fights. Moreover, there is a belief that a woman’s metabolic adaptive effect (rebound if you will), post weight-cut, may be greater than a man’s so again having a weight cap will be crucial. She is also going to be less effective at water turnover, as she does not have as much water to release as a male fighter, as previously stated. This is in part due to lower total body water, menstruation, hormones, and a reduced capacity to sweat. While the number of sweat glands for relative mass is higher in women compared to men, sweat glands in men seem to activate sooner and produce more sweat per gland unit. This was demonstrated in a study via Japan’s Osaka International University. Additionally, research has shown that testosterone may also play a role in increased sweat rates in men. Hence, as stated, women will need to rely more on reduced body fat, with an increased weight-cut duration/camp to arrive at scale weight as compared to their male counterparts. While men should also rely on making the scale with the least possible percent of body fat at which they can perform at optimal levels -- they will likely have the ability to release more water and restore/rehydrate water quicker than women in the final stages of the cut. For your females, consider keeping the body fat well-regulated between fights and anticipate setting forth a long-term weight-cut plan. [8] 6) Historical Dietary Practices – Whether or not you are managing your fighter’s diet through the camp -- and we hope you are -- nutrition practices during their previous cuts, and traditional nutrition habits outside of camp, will provide insight into whether their cuts were methodical and efficient, or why the cut was the equivalent of waterboarding. If metabolism can adapt to extremely high training volumes and intensities, coupled with sustained periods of caloric restriction -- and we have reason to believe it does so in many -- you want to have knowledge of this. If your fighter was eating minimal calories for a substantive portion of the camp, and did so for several camps, then the aforementioned issues with adaptive metabolic effects may be at hand. We emphasize this only so we know it may be a potential problem, if not - great! It will be challenging to convince a fighter used to starving for cuts, then post-fight eating whatever he/she wishes, to eat adequate amounts of protein, carbs, fat, and foods of extremely high nutrient density and not leave room for much else, come cut time. But, they have little choice. However, if they eat perfectly year-round, train year-round, and are in elite shape year-round, like WBO Junior Welterweight Champion - Chris Algieri, (our colleague at the Fight Science Institute) then there may be little need for major dietary modifications. Furthermore, knowledge of long-term fluid intake is also crucial because it will influence water turnover. Those with historically low fluid intakes may not only be inhibiting performance and skill acquisition, they may not be maximizing water turnover and sweating ability. And yes, for most the ability to sweat can be improved, and if it can, we should improve it. Moreover, when trying to drop the last few pounds, this ability is crucial because we want the last few pounds in water to release easily, and passively, not only by intense activity in steam or sauna. As a note, keep in mind when cut time comes you must develop a nutrition plan and daily caloric values for your fighter -- which you may obtain through a metabolic equation such as Mifflin-St. Jeor and an activity multiplier – but these can usually yield high calorie values and your fighter is not likely to reach their cut goals on the numbers derived through such formulas. You will need to formulate a daily calorie intake number somewhere between the previous restriction number they had in camps, and the number acquired through metabolic equations (more on calories will come in chapter 4). In summary, our goal in the Assessment is to consider every potential factor that may influence weight-cut success. Of course, our book cannot address every potential factor, and some are unforeseen. Nonetheless, gathering all possible information on your fighter -- whether they are an “up-and-comer” with limited cut experience or a 10-year veteran -- will help account for all variables (good or bad) affecting your ability to create effective weight-cut strategies for a successful training camp and optimal performance come fight night. The goal of a camp is to prepare all biomotor abilities to excel for the duration of a specific fight, all while enhancing motor skill, fueling the brain to concentrate, and remaining mentally strong. [9] An effective weight cut preserves all of this! Our goal is always to optimize performance, not tempt it!! The Assessment like all we do, is designed to foster thought and give rise to more questions and solutions that will not only increase the safety of weight-cuts, but also develop strategies that allow fight-sport athletes to enhance performance through this phase of preparation. Coach Ricci with former UFC middleweight champ Chris Weidman and three-time European world kickboxing champion Daria Albers [10] Chapter 3: Data Acquisition All too often fighter’s say that they need to make a particular weight, and we ask, “well what the hell are you getting rid of to get there?” As an example, some fighters may tell us they need to make 155 pounds (156 pounds for non-title bouts). At this point, they are 185 pounds with six weeks to go before weigh-ins. Somehow, they make it, and then have some time (maybe around 30 hours) to make up for the hastened cut with a better planned rehydration protocol. With this approach to weight-cutting, all too often fighters lose too much of what they need, and keep much of what they don’t, for the fight. To fix this we need some numbers! Therefore, the minimum data acquired before the cut must be current weight, body fat percentage, lean mass, total body water (TBW), level of hydration at current bodyweight, BMR, and even (while not crucial) anthropometric measurements. The additional tool we mentioned earlier for Data Acquisition, MuscleSounds Technology, which provides an estimate on skeletal muscle glycogen status, is worthy of inclusion as well. Overall, the goal is to get some numbers and use them. They may not be perfect, they may not add or subtract precisely, and we may have to do our best to manipulate them wisely as most of what we do in weight-cutting is without the existence of significant scientific precedent. Coach Ricci uses the BodyMetrix on UFC middleweight fighter Elias Theodorou In the beginning of this book, we discussed an investment into some effective tools. Hopefully, as times goes on, all of the necessary equipment will cost less than a refurbished iPhone 4s, and aspiring coaches just getting started can gather useable data with low cost. [11] In the interim, we are not going to tell you to get a DEXA machine (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, now a gold standard in the field) and spend $80,000. Not to mention, when traveling with fighters, the DEXA is a bit heavy, and tough to get it through security. Fortunately, DEXA scans are becoming more readily available as more physicians have them, and the pricing for the scan is becoming affordable, should you decide to use it. The other option is to get your fighters to Las Vegas and have them frequent the UFC Performance Institute. The Institute includes Head Strength Coach - Bo Sandoval, Performance Director - Dr. Duncan French, and the Director of Nutrition - Clint Wattenberg. They can run the DEXA for you and provide a host of other valuable measures. It is an amazing facility and the aforementioned individuals are an incredible team. However, in the interim, about four years ago Ricci was introduced to the BodyMetrix ultrasound body fat machine. It is produced by Intelametrix, and has become a viable option, when not in the lab, and when in the gym or on the road. Both Daru and Ricci have used it ever since. The BodyMetrix is portable, and there is favorable data to support its use. Dr. Brad Schoenfeld ran a study comparing it to a Bod-Pod (air displacement plethysmography), showing a similar degree of accuracy between the two. To those in the industry that have been doing this for some time, you know portability is crucial as you may have to move amongst fight gyms, and travel with your fighters during camp (in the data graphics section in the back of this book you will find data provided by the BodyMetrix). However, if you do not purchase a BodyMetrix, body fat can be measured with calipers, and hydration status with a refractometer. Why is the acquisition of this information so important; because, we want to know what we have to drop to get to the scale, should we drop it, or can we even achieve the goal at all! The BodyMetrix (or an impedance device) will give a nice estimate of body fat percent, total body water, total lean mass, and perhaps a reasonable BMR estimate. Let’s demonstrate the importance of this data with this example: We have 2 fighters that wish to fight in MMA at 185 pounds: Fighter 1 is 6’1” 212 .lbs, 16 percent body fat, and a TBW of approximately 63% Fighter 2 is 6’3” 212 .lbs, 9 percent body fat, and a TBW approximately 68% Let’s assume both are fighting each other in nine weeks. Without any information on the aforementioned factors, they are equal in how much they must lose to arrive at their designated weight. Although, they are not at all equal in how they will arrive at that weight. If we assume, based on assessments, that Fighter 1 can fight at 10 percent body fat and perform well, and Fighter 2 fights optimally at 7.5 to 8 percent body fat, how they get to the scale, and what they lose to get there will be dissimilar. Fighter 1 will have a substantive portion of weight-cut coming from fat. Fighter 2 will need to cut much less from fat, and instead more from muscle and water. Who is better off? That depends on many factors. Firstly, should either even fight at 185 pounds? [12] That is a decision for the head coach (with your counsel), sanctioning bodies, and the fighter. However, to reiterate a primary point, this book’s goal is to remove the arbitrary nature of weightcutting and project what weight may be possible. So, let’s calculate the potential arrival weight at the scale using Fighter 1. Are these numbers perfect? No! Are there more things we may lose, and some we have not accounted for? Certainly! Nonetheless, with careful management, you can control as many variables as possible to arrive to the scale methodically, and with enhanced performance. Here we will formulate/predict numbers for a Middleweight fighter. Fighter 1 Example: We have an MMA Middleweight weighing 212 pounds, has 16 percent body fat (33 pounds), and 63 percent TBW. He must make, no more than, 186-pounds max weight on the scale. We are 10 weeks out. Can we make it? 212 .lbs – 14 .lbs = 198 .lbs (212Ibs is 26 pounds over 186 scale weight, approximately 15 percent above scale, not great. We have determined this fighter can perform well at 10 percent Body Fat (BF) = - 14 .lbs of fat) Fighter is now 198 pounds, approximately 67 percent water, as fat percent goes down, total body water percent goes up. 198.0 .lbs – 2.5 .lbs = 195.5 .lbs Independent of the efforts, with well-regulated sleep, protein, fluids, supplements, some resistance training, almost all research demonstrates that there will be some lean tissue loss, especially with high training volumes, and moderated caloric intake. We are being very conservative with a 2.5-pound loss of lean tissue on our fighter, but we will keep it tight. 195.5 .lbs – 1.0 .lbs = 194.5 .lbs Fighter is now 194.5, +8.5 pounds away from the goal weight. While this is often overlooked, and we cannot validate it perfectly yet, a 195-pound fighter is likely to store a range of 100 grams carbs (CHO) in the liver, and approximately 450 grams in skeletal muscle. So yes, a modest reduction in CHO the week of the cut, in the range of 125 grams less glycogen, would translate to approximately 375 grams of water as storage. This is a 1:3 glycogen to water ratio as for 1 gram of glycogen, 3 grams of water is stored. We total about 500 grams in weight, just over one pound. The -150 grams of CHO can easily be replaced in a 30-hour window. 194.5 .lbs – 0.5 .lbs = 194.0 .lbs Where did this half pound come from? While fat tissue is hydrophobic, there may be associated water loss as some water is contained within the extracellular space of adipose tissue, and undetected IM/visceral fat. Additionally, the lower levels of body fat may lead to hormonal ratios that favor water release and lessened inflammation. [13] Is this a bit of a reach? Yes! However, sometimes in weight-cutting, we need to find potential variables to further weight loss. Eight pounds to go and this will need to be all water. Can they make it? This will be a water cut from about 194 to 186 pounds, or approximately 4.0 percent bodyweight. Obviously, a large number when all fluid. Do most make this? Yes, and easily, but we leave the decision to you and team if this is feasible. However, this is why calculating potential numbers in advance is so valuable. We ran the numbers and we projected the potential way our fighter may arrive at the scale. These numbers, while a framework, do offer some reasonable insight into whether or not we can get there. The numbers are interchangeable as some fighters may lose more muscle, need to pull more glycogen, or require other combinations. However, we gave this example under optimal conditions because that is what we are trying to create. Dropping 14 pounds of fat in 10 weeks is highly possible. You may wonder why we are so focused on maximizing fat loss and finding the optimal lowest fat percent number at which your fighter can perform. Well, that is because for every pound of fat we do not cut, it is another pound of water we must drop, and potentially more muscle mass that must be removed. In every cut we will lose some muscle. In our fighter, we calculated 2.5 pounds of muscle loss. This is very conservative, because we are going to try our best to limit the loss of lean tissue (how is discussed in the Camp Management section). Yet, data by Morton et al., shows weight-cuts with much greater loss of lean mass, (and most cuts do) as shown in Table 1 on page 17. So we will need to be strategic to prevent such. We were able to have a small glycogen drop due to the large fat loss, but it will translate to some weight loss on the scale. A fighter may have the ability to make weight without a substantive cut in carbohydrates/glycogen the last week, but again, they must be close enough to the scale weight, with maximum body fat lost, and a remaining water cut of somewhere best in the range of 3-4 percent of bodyweight. Regarding our additional numbers, is there residual weight loss that occurs with fat loss, as explained and shown with the cut numbers? We are not entirely sure, but there seems to be from the scores of weight-cuts we have performed at the elite level of fighting. Our water cut of 4.0 percent, is this a dangerous number? By performance standards, it is. The fighter will perform with significant decrements in physical and cognitive abilities with that much water loss. However, we must remember that water is a refundable facet of the weight-cut because we can immediately replace it and then effectively redistribute it, and the necessary electrolytes, in the potential 30-hour window from the scale to fight. Again, we are neither condoning, nor denouncing whether cutting this way is appropriate. We are simply acknowledging the way we navigate through the current practices, while doing all we can to reduce health risks, preserve performance, and maximize the refueling and rehydration process. As a note, most fighters would sign up for the example numbers in this mock cut every time, and so would we. [14] Yet, Ricci’s work with welterweight Ryan LaFlare is a good example of the difficulty of these practices. LaFlare left on a Sunday for Brazil, to fight the following Saturday. He had to weighin at no more than 171 pounds. He left that Sunday at 184 pounds, with a 4.8 percent body fat, and a total body water of 69.5-70 percent. Total body water had better be that high if body fat is that low. Even with those numbers, LaFlare made weight, and beat a local fighter from Brazil that who had the advantages of minimal travel. By the numbers used in our calculations, it would have been hard to see how we would arrive at 171 pounds. However, you will experience this dilemma with fighters such as LaFlare, who are first incredibly tough, naturally low in body fat and remain large for a division like welterweight, but lighter for the next weight-class up. As cut coaches we of course try to avoid such a drastic cut, and keep the fighter healthy and at high-performance! Although, when good money is on the line, the fighter will find a way to make the weight since this is their chosen career, and it’s a career with a short life span. In addition, you must also consider that any of the numbers we looked at here may vary amongst fighters, or even vary with the same fighter from fight to fight. While what we proposed as a methodology to get to the scale is not perfect, it will provide a sound framework from which to begin. It is a practice which many of you may advance and perfect further. Key Factors in Data Acquisition 1) Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) – This is imperative to acquire, because we will at least need a framework of calories to center our energy intake on at the beginning of a camp. The optimal way to do this is through gas exchange/VO2 testing, but we are not going to ask you to spend $10,000 on a CardioCoach unit. If you choose the BodyMetrix Ultrasound System, or a Tanita Impedance system, you can get an equitable BMR estimate based on lean mass. A great device of reasonable cost is the BodyGem. It is a validated piece of equipment for getting accurate BMR results. If you do not have access to these devices, that is okay. However, it is worthwhile to invest in a pair of skinfold calipers to get estimates on the fighter’s body fat and lean mass. Then calculate your BMR numbers by putting them into a Mifflin St. Jeor equation (easily populated online). Whether using a formula or device for BMR, feeding the lean mass in a highly overweight fighter who is cutting is likely to give you a better starting caloric intake, than feeding total body weight. This is especially true once you use an activity multiplier in these equations, as this really heightens the total daily caloric intake number. We discuss determining BMR and daily caloric requirements in further detail in the Camp Management section. 2) BioMarkers – Essentially, this is blood-work. You must understand that this is not practical for every fighter and coach. However, companies such as BluePrint for Athletes and Inside Tracker provide services that are mobile and becoming relatively affordable. [15] The goal of biomarkers is to get pre-camp numbers on testosterone, free-testosterone, cortisol, cholesterol, triacylglycerols, blood glucose, sodium, potassium and more. Having a baseline of these markers is highly valuable and only one or two subsequent measures may be required during camp for monitoring the fighter’s physiological response through it all. Monitoring can help ensure that your fighter remains within their previous norms and may help determine over-reaching should it occur, and elucidate favorable responses to training as well. 3) Heart Rate/BP/HRV- Resting heart rate (RHR), while not directly correlated with the cut itself, can be useful and acquired without purchasing a monitor. Knowing RHR from the beginning ensures as camp progresses that there’s not a substantive increase in RHR, but hopefully a decline as an indicator your fighter is recovering suitably. A blood pressure baseline can also provide insight into recovery and levels of hydration, particularly in cutweek. These measures in camp are helpful. With heart rate variability (HRV) we need a device such as the Polar V800 (about $350). This provides data on sleep, VO2 (with 92 percent accuracy), and HRV. Yet regarding HRV, the jury is still out as to what exactly it means, and what to do with the numbers. Don’t sweat over HRV right now. RHR, BP and HRV, while not required, do provide insight into recovery and the important balance of the sympathetic nervous system (acceleratory) and parasympathetic system (Restorative). 4) Anthropometric Measurement – This is quite cost-effective. While we won’t gain the most sophisticated data, it’s safe to say if your fighter’s waistline is remaining relatively stable throughout camp, and their legs, arms, and neck are decreasing in size, they may be losing muscle. For this reason alone, measurements are useful! 5) Glycogen Storage – Earlier we mentioned MuscleSounds glycogen technology. There is much to be validated and learned about this technology. Nonetheless, we are considering its use at the beginning of camp and establishing a baseline reading of near max-muscle glycogen storage. A potential way to do so is to allow generous carbohydrate feedings over one or two days before camp starts. Then lower training volumes, in an attempt to establish a reasonable glycogen saturation/status number, and then compare the glycogen status through camp as to ensure fueling status during camp, but also after weigh-ins. Again, this just a marker of which we want to make you are aware for future use should you decide. In summary, Daru and Ricci like to have all possible numbers. This doesn’t mean they will be relevant at a specific point in camp or training. But, they teach us about trends over time or offer insight into future practices in weight-cut and performance training. The actual acquisition of numbers is itself a learning process. As stated, some of the equipment is costly, but it is not required. Our hope is as you and your fighter’s advance, so will your financial resources and these measurements and tools can become a part of your future programming. [16] Table 1 A graph depiction From Morton, et al. Case Study, Making the Weight, International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 2010, 20, 80-85 The table shows a featherweight boxer during a 12-week cut by Morton, et al. Starting at about 69kgs (151 pounds), with the goal of losing 10kgs (22 pounds) to make super-flyweight. Which is at 59kgs (129.8 pounds). The athlete dieted on a caloric intake equivalent to his BMR, 40 percent carbohydrates, 38 percent protein, and 22 percent fats. This is a low caloric intake based upon such high training volumes. Over the 12-week intervention, the fighter lost about 5.1 percent body fat, approximately 4kgs (8.8 pounds) of fat and 3.8kgs (8.3 pounds) of muscle. Obviously, this is a significant amount of muscle tissue. As addressed earlier, this is why we set a number of about 10 to 12 percent above scale weight as a cap. The fighter was as high as 17 percent above scale. This excessive loss in short time will almost always lead to dropping much more muscle. In summation, our earlier ultra conservative number of 2.5 pounds of lean tissue loss is just that, ultra conservative. Why so conservative? Because our fighter, weighing nearly 55 pounds more than this boxer, lost only five pounds more total weight. And, inherent in our example is that our MMA fighter is likely doing more resistance training and eating about 2.0 g/kg of bodyweight in protein, both which preserve lean mass. He also has a higher caloric intake per pound of bodyweight and we are ensuring full sleep and recovery. However, our fighter example elucidates why the potential fat cut should be maximized, because if our fighter starts at 16 percent fat, and only moves down to 12 percent, while they could fight at 10 percent that would require our fighter to lose approximately another four pounds in water. Cut the fat slow and effectively and we will preserve more muscle mass, and maintain/improve power, speed, strength and endurance. [17] Chapter 4: Camp Management In our discussions thus far, we put much emphasis on obtaining both subjective and objective information. With the purpose of attaining an understanding of where the fighter has been, how they got there, how many times they got there, and where are they going. In this section, we will discuss variables we can manage as our fighters traverse a weight-cut while simultaneously improving conditioning and sharpening fight-specific skills during their camp. As we address some of the basic variables we can manage in camp, it will end up leading to more questions. Obviously, we cannot address everything that may happen, whether predictable or unforeseen. Inherent in much of what we are writing is the assumption of a fighter who is practicing reasonable adherence to our programming. If not, then we have a fire sale on our hands, and all the dangers and hysteria of weight-cuts will come to pass. Nevertheless, we will start with an example of a 10-week camp and keep to the same numbers we ran on our previous fighter. Daru with his Boxing, Bare Knuckle and MMA Crew 1) Training Schedule – As dynamic as it may be; try to obtain your fighter’s camp schedule in advance, or at the very least, a framework of what it may look like. You will want to know the days that afford the highest and lowest training volumes, sparring and complex skill days, as well as the timing and duration of sessions. This helps you manage a host of variables related to your fighter’s weight, such as fluid intake, the timing of meals, what to include in those meals, how much food in each meal, and when we can recover. [18] Schedules will rarely hold exactly to plan, but you must be in the loop on what your fighter is doing and when. This is especially true if you’re managing your fighter’s diet and cut, and you’re not on location with them. Your input could be useful when trying to properly adjust training volumes, speed up or slow down weight loss, adjust calories and/or macronutrients, and design recovery strategies. Are we micromanagers? No - but we like having micro-information if you will. 2) Weight – As camp starts, we can only hope the fighter remained in sound condition and kept weight within the cap of 10 to 12 percent maximum above scale weight. If not, the early weeks of camp will be spent in weight reduction, and as a cut coach you will to want to get some weight off quick. The associated wear and tear on a fighter’s body (joints in particular) when they are considerably overweight, is excessive. Additionally, when they are so de-conditioned they are losing valuable time to enhance effective skill acquisition through training since they likely fatigue quite quickly. The old saying, “You have to be in shape before you can start training,” is never truer than it is in fight camps. As camps start take weight and use the body fat data to start predicting the feasibility of arrival at scale weight. It will be important to monitor weight throughout the camp with as much frequency as possible. Because you want to have a working knowledge of the rate of total weight loss, the rate of fat loss, degree of lean tissue loss, and fluid turnover through each training session. If we spend nine of the ten weeks in cutting, we can assume that 1.5 pounds per week on a 212-pound fighter would translate to about 13.5 pounds of fat one week prior to the fight. That would put your fighter at about 198.5 pounds, for 186-pound scale weight one week out, excluding the lean tissue loss contribution to the scale. This would be deemed in our perspective, great positioning, and close with recommendations such as those put forth by the CSAC. These numbers work out nicely here. In a real camp there won’t likely be such a systematic weekly linear decline in weight. However, even if the weight is undulating in how much is lost on a weekly basis, you will be in touch with your target, and where you are in relation to scale weight at all times. Evidently, if your fighter was 220 pounds, and has to make a maximum of 186, we need to lose more weight quickly. So yes, of course the rate of weight loss will vary according to where the fighter has started and the total number of weeks in camp. Our success in managing the weight comes from constant monitoring of diet, fluids, sleep, total training volumes and duration, which should lead to effectively dropping fat and holding as much muscle as we can. Track these numbers, keep your fighter and skill coaches updated, monitor their energy and focus through camp up to the scale and, you will get them there safely. [19] 3) Nutrition – This section is a book unto itself, and no topic is more hotly debated than nutrition, independent of the objective. There’s no way we can propose every viable option as to how to construct a weight-cut diet, how to adjust it, and then adjust it again. Perhaps one of the reasons there is so much diversity in opinion, and to an extent in the data, is because we all have metabolic individualities that not only differ from each other, but may vary within each individual at different points in time. So please, look at our information as an overview, and for everything we discuss there will always be a counter argument -we are fully aware of that. For the sake of brevity and clarity - we will make a checklist of strategies for developing an initial framework of eating for your fighter. Calories - There are so many factors to determine just how many calories your fighter will need at the start of camp. Chances are it’s not as high as we tend to think. Certainly not if it consists of good food. However, some of our options have been discussed already. You can use this Mifflin St. Jeor equation to get BMR (Basal Metabolic Rate) Male BMR = 10 × weight (kg) + 6.25 × height (cm) – 5 × age + 5 Female BMR = 10 × weight (kg) + 6.25 × height (cm) – 5 × age – 161 Today, you do not have to manually do this. Ricci is an old man and used to do these equations with Ben Franklin (sarcasm laid on thick here), but as stated before, they are now easily populated online. If you have any of the aforementioned equipment, you can use this to determine BMR the number of calories your fighter will need at rest. If you have no equipment, and don’t use a formula, you can estimate a BMR by obtaining your fighters weight, and simply multiplying this by 10. It can give you a number surprisingly close to the other formulas. So as an example, 212 pounds x 10 = a resting BMR of about 2,120 calories per day. You should add to this based on the frequency, intensity, and volume of training sessions. Activity Multipliers help us do this: 1.200 = sedentary (little or no exercise) 1.375 = light activity (light exercise/sports 1-3 days/week) 1.550 = moderate activity (moderate exercise/sports 3-5 days/week) 1.725 = very active (hard exercise/sports 6-7 days a week) 1.900 = extra active (very hard exercise/sports and physical job) In this case, you would take the BMR of 2,120 and multiply by these activity factors.(Above) Now, obviously a fighter qualifies as very active, or extra active, but this is likely going to give you a caloric intake well above what the fighter needs for an effective weight cut as it would add to well over 3000 calories. This is especially high if they are starting camp well above the 10 to 12 percent above scale weight and have a history of brutal weigh-cuts. With that in mind, we have to estimate a number. About 600 calories above BMR may be a good place to start; meaning 2,800 calories total. Please consider this is as an estimate. [20] If the fighter loses weight rapidly over four days, has little energy, and is extremely hungry, bring those calories up in the range of 200-300 daily. If there is no loss over a 4-5 day period, bring them down some. This is where the art of cutting comes in, as the numbers don’t run perfectly. Also remember the following: we can eat a lot of healthy, nutrient dense foods, within about 2800 calories which would be a good start for our fighter. In this case, that number will be in reference to the 212-pound fighter. Sample 2800 210 grams of Protein x 4 calories per gram = 840 Calories 325 grams of Carbohydrate x 4 calories per gram = 1300 Calories 70 grams of fat x 9 calories per gram = 630 Calories 2770 Calories Some will consider the estimated 2800 calories to be far too high. It may be but we have a pretty big fighter starting camp with likely 3 training sessions per day, and we must cut fat, preserve lean tissue, and provide as much nutrient density as possible. Even if it is a bit high, we can adjust immediately. Some may consider it too low, and you may be right as well. Accordingly, depending on your fighter’s history of weight-cuts, dieting experience, metabolism, and other factors for you to discern, you may have to adjust these numbers. However, feel confident in the fact that this is a sound start, and you are in the beginning of camp, so this is the right time to do it. Your fighter is not going to gain fat at these ranges, based on his weight and will not starve either. You are in excellent position to make effective adjustments. If your fighter is wired with any device that may estimate caloric expenditure throughout the day, definitely review it. These devices will not give precise measurements on caloric expenditure, but they may help you make decisions on approximating how many calories you need to add or subtract. Now, as camp progresses, much changes. Hopefully our fighter is dropping some fat so weight is going down. Consider, as body mass decreases from fat and some lean tissue, BMR is likely to decline (use formulas or your equipment to adjust calories accordingly), yet simultaneously, training volumes are going up. This will have us not only adjusting calories, but perhaps macronutrient distributions too, which we discuss next. [21] Sample of 2700 Calorie Diet at Start of Camp Macronutrients - The distribution of macronutrients is one of the most debated topics in all of nutrition, but we are not here to argue it. For your fighter’s camp, distributing macronutrients will be contingent upon all we have discussed. Such as how far is your fighter from scale weight, and even previous dietary habits. What we do to start is build the distribution of macronutrients around protein. Why is this? Because it’s not often you are likely to hear someone say, “I want to get this protein off my waist before the summer starts.” There is no excessive storage pool for protein as there is for fats (as triglycerides) and carbohydrates (as glycogen). We must ensure we get sufficient amounts to not only preserve lean tissue, but enhance strength, speed, power, and all of the biomotor abilities which the camp is intended to heighten. With protein deficiency, especially when calories may be cut drastically, none of the goals of increasing performance are likely to be maximized. For building muscle mass, and/or maintaining muscle mass, through a positive muscle protein balance/nitrogen status, the International Society of Sports Nutrition (ISSN) recommends an overall daily protein intake in the range of 1.4 to 2.0 grams protein/kg/bdwt/day. This balance is sufficient for most exercising individuals and is a value that falls in line with the acceptable macronutrient distribution range published by the Institute of Medicine for protein. Of notable importance for this protein range, is that it also assumes sufficient caloric intake, with suitable amounts of carbs and fats. As we already discussed, we will be on the border of balanced caloric intake for camp, and in deficit for much of it. [22] Infographic from YLM form review of Hector & Philips, providing a great illustration of protein demands in caloric restricted athletes. In a review by Hector and Phillips, they made recommendations for protein intake, during weight-loss in athletes, at 1.6 to 2.4 grams protein/kg/d. This has a direct correlation with our fighter. However, the severity of the caloric deficit, type, and intensity of training performed by the athlete, will influence at what end of this range athletes choose to be. Other considerations regarding protein intake, that may help elite athletes achieve weight-loss goals, include the quality of protein consumed, and the timing/distribution of protein intake throughout the day. We can write pages about protein’s importance in weight-cut athletes, why it preserves lean tissue, and why its thermogenic effects keep athletes lean. Nevertheless, this is not a diet book. Our general message here is as follows, the more weight your fighter has to lose, the more they may have to rely on high protein intake and a moderated, or even limited, carbohydrate and fat intake. We are not condoning the absence of carbs and fats, just emphasizing that under the caloric umbrella administered through much of camp, we must manipulate the three macronutrients according to how much weight we need to lose, and the volume of activity that day. If your fighter is in great condition, then perfect! You may be able to keep those carbs in the range of 50 percent of total calories. If they are 20 percent above scale weight at the start of camp, carbs may need to be much lower, fats moderated, and protein high. Previously, we mentioned the importance of knowing the training schedule. One reason why this is useful is that in the weight-cut process, we can increase the carbs slightly on high volume training days -- sparring days for an example and then lower them on reduced volume days, or off-days. [23] Studies examining martial arts have found that the energy demands of an average fight or sparring session, lasting four minutes and 27 seconds, derive approximately 77.8, 16.0, and 6.2 percent of its energy demands from aerobic, anaerobic, and lactic energy pathways respectively. Therefore, information like this is certainly noteworthy for sparring days. It does not mean we must manipulate macronutrients within micro percentage points to properly fuel such sessions. We can just make small adjustments accordingly. The greater significance of this data however, is the insight this may provide to potential fuel mixtures during fights. Where does this leave us? It leaves us with aiming to get our fighter about 2.0 grams of protein per kilogram of bodyweight, then multiplying protein in grams by four. This establishes our calories in protein, and then we can distribute the remaining calories in carbs at four calories per gram, and fat at nine calories per gram. Sample of how to breakdown macronutrients: Total calories started at 2800, for our fighter of about 212 (96.4) pounds 2 grams protein per kilogram, approximately 193 grams x 4 = 770 calories Now have 2030 calories to divide amongst fat and carbs. 300 grams of carbohydrates = 300 x 4 = 1200 calories so 830 remain 830 calories remain for fats 830/9 = 92 grams of fat While taking our approach to macronutrient manipulation is not required, hopefully this information is valuable in developing dietary applications for your fighter and also serves as a guide to potentially manipulating macronutrients as needed. Nutrient Timing – Much debate remains as to whether there is an optimal anabolic window, and how long that window stays open. For example, should someone eat protein right after lifting weights to get maximum benefit, or do they have much more time? This is an erroneous argument for fight sports as fighters train two or three time a day. They turnover many pounds of water daily and the metabolic expenditure of nutrients are extremely high. We cannot allow fighters to wait to eat, even during weight-cuts and cannot allow delays especially when it comes to fluid and electrolyte replenishment. The table on the next page provides an excellent overview of macronutrient timing in a hypothetical camp schedule and is framed from the article: Making Weight in Combat Sports. [24] Sample Nutrient Timing Plan for Camp - approximately 300 grams of Carbohydrates & 210 grams of Protein 4) Fluids – There may be nothing more important in relation to performance than water/fluids. Considering humans may be able to survive well over a month without food but cannot survive more than several days without water. It’s safe to say water is crucial to survival and the foundational nutrient of athletic performance. Firstly, most of the research we have on fluid intake elucidates how much performance declines with commensurate declines in fluid related body weight. At two percent for example (which would be about 4.5 pounds on a 212-pound fighter) we will witness a clear decline in performance. While we have sound data on how much to replace after loss (about 125% of total loss), knowing how much an athlete needs to consume daily during activity/camp is less established. Yet, we will propose a few strategies that we have used to noteworthy success. They certainly make physiological sense, but research strategies for optimal fluid intakes that foster water turnover, efficient sweating, and re-absorption rates, is limited. First, the goal with fluids is to keep fighters hydrated, optimize performance, mental concentration, enhance skill, and reduce the risk of dehydration related injuries. Second, we want a high fluid intake and efficient sweat rates during training or in sauna recovery. Third, by consuming high fluids in camp, this should allow water to release effectively (sweat-urination) in cut week, especially the last few hours of cutting to make weight. Why focus on this during camp? Because, if your fighter has to drop six or seven pounds of water the night before the scale, we want a body that is trained to release a substantive amount of water with effective ease. The last thing we want is a fighter cutting water on a Thursday night, under nine layers of clothes in the steam room, while hitting pads. [25] We do not want to have extreme taxing of the body the last few hours of a cut. Other than the skill coach’s decisions on where and when to keep the nervous system active before the fight, we best not tax it to the extreme for cut purposes. This proposes the question: How much water daily does a fighter who may be training three times a day and turning over/sweating 10 pounds of water daily need between loss and replenishment? Well two things which have a sound basis are how much fluid to ingest during intense activity, and the estimated intake required for refunding fluid loss. At some point, fighters are likely to have two, if not three, training sessions daily. Perhaps they are not all intense, nevertheless, usually they are enough to produce reasonable amounts of sweat. Approximately 16 to 20 ounces/hour during each training session for our fighters in the featherweight (145 pounds) and lightweight (155 pounds) class, is a sound start. Then up to 20 to 25 ounces for middleweights (185 pounds) and light heavyweights (205 pounds) should be suitable foundations. You can adjust this through camp according to training intensities, volumes, temperatures, and before and after weight assessments. A vital practice, and one that should become ritual, is before and after practice weighing. This not only gives us a number for which we need to replace but helps us determine if there are changes in rate of sweat commensurate with hydration levels, or adaptive changes in sweat rates at a given training intensity and volume. For this, we will use a simple International Society of Sports Nutrition (ISSN) number. For every pound loss, we need to consider a fluid intake of approximately 125 percent to recoup that pound. Therefore, if your fighter has sweat off three pounds in practice that will equate to 48 ounces lost. Then we should consider a fluid ingestion of about 60 ounces. This becomes quite a bit of fluid loss if there are multiple sessions in the day, making for even more to be consumed. We have made recommendations for fighters to try to aim for a minimum daily fluid intake of about 75 percent of their bodyweight in ounces. While this may seem very high, and most will not meet this, it is often better to shoot high and miss, then aim low and hit. However, this recommendation is not without rationale as we look at numbers. Example: Two training sessions daily with six pounds total water loss is equal to 96 ounces. With 125 percent replenishment this becomes 120 ounces of intake. Water during two training sessions, 20 ounces/session at camp bodyweight average of 205 pounds leads to an equation of: 120 oz + 40 oz = 160 oz (to replenish) Therefore, we have reached well over a gallon just to support training and replenishment. We will need water for metabolism, the brain, organs, plasma and so on. Meaning an additional 30 to 40 ounces is quite logical, and puts us near this fighter’s body weight of fluids consumed in ounces. [26] In finality, we are carefully trying to keep an optimal fluid balance during camp. This will entail monitoring hydration/total body water, ensuring fluid intake during training sessions, taking pre and post training weight to ensure sufficient rehydration, additional fluids to support daily metabolism, and a dense intake of electrolytes via sport drinks or powders. In addition, you always want large intakes of nutrient dense foods. Why do we support such high fluids? Well one reason, our bodies become more efficient during many different processes, such as quicker restoration of heart rate recovery from training or becoming more expedient at replenishing glycogen. Therefore, we want to practice the efficient release of fluids/sweat during camp, then enhance the ability to improve immediate fluid and electrolyte replenishment back to the cells and the proper compartments in the body (Ricci has been investigating tools/patches which measure electrolyte levels in sweat, but to date, accuracy remains debatable). This is why we do not adhere exclusively to the practice of water loading days before the scale. Just as we would not cardio-load, skill-load, or spar-load five days before a fight; relying on high fluid loading only in cut-week may not maximize the aforementioned abilities of the body. Therefore, we are proponents of the long-term practice of high fluid intake for optimizing turnover. We are confident that this practice in camp (not waiting to the last week only with water loading), will make the release of those last few pounds easier, and increase the speed of rehydration and electrolyte distribution once off the scale. In the Cut Week and Rehydration chapters we will further discuss factors effecting fluid release, fluid balance, and restoration. 5) Training – As we focus on weight-cutting, in-depth discussions of skill training, and strength and conditioning are not addressed within this book. However, for those who govern both the cut and performance training, you understand the delicate balance between the two. Actually, this is the reason behind Daru and Ricci’s efforts with the book. Both grew frustrated taking part in successful camps as performance coaches, and witnessing 10 weeks of enhanced conditioning, advanced skill acquisition, and heightened mental focus, relegated to ashes in 48 hours. This was due to nutritionist/cut specialists with no long-term weight-cut strategies, questionable cut-week practices, and reckless rehydration and refueling protocols. To an extent, we have addressed many aspects of training already. Of great significance is collaboration with the skill coaches, as to aggregate the (scheduled) projected training volumes and timing of sessions throughout the day. This helps ensure that food and fluids can be inserted accordingly, and with the proper volumes. Additionally, if you are designing the conditioning program as well as the cut, you can develop your programming to fit within the framework of the skill training. Strength and conditioning is important, but skills training always takes priority over it in proper fight preparation. Once we have the training times, volumes, and intensities, we can regulate calories, fluid intake, and closely monitor weight loss. As mentioned many times, this is all a rational estimate and framework, but guessing does not offer, either. [27] Developing your own table such as the one below, from Harvard Health Publishing (via Harvard Medical School), is valuable to have on-hand. This is strictly an example, so you can monitor an estimated caloric expenditure throughout the day, and adjust if needed, commensurate with the rate of weight loss. These sessions’ calorie numbers would be added to the BMR you established at the camps start and adjusted as your fighter loses body mass. Calories Burned in 30 minutes of Activity Discipline 125-pound person 155-pound person 185-pound person Boxing 270 335 400 Kickboxing 300 372 444 Wrestling 180 223 266 Conditioning Circuit Training 240 298 355 Weight Lifting 180 223 266 Jump Rope 300 372 444 Running 8.6mph 7 min mile 435 539 644 These figures are estimates, and vary, according to the athlete or the modality through which they were extracted. Furthermore, as we addressed in the nutrition section, along with knowing potential caloric requirements and expenditure, it is useful to remind ourselves of the energy system and fuel mixtures that occur during camp, or how they may vary from day to day. These fuel mixtures of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins (as a percentage of consumed fuel) are going to vary greatly on a daily basis. Nonetheless, this further reinforces why monitoring training volumes, frequencies, and intensities is essential. At this point, if there has been an incessant emphasis on certain data, at least we succeeded in consistent messaging. We must understand monitoring training during camp to manipulate water, calories, or macronutrients, commensurate with changes in body composition. However, of equal significance, is to watch, and dialogue with the skill coaches about your fighter’s performance during camp. We don't just have a scale landing to worry about, we have a rehydration and refueling protocol that must take us to the return weight at which the team decides the fighter can perform optimally. The weight at which your fighter will perform optimally should be determined well in advance of the fight. [28] Daru and Ricci have the fortune of spending much of their work time in fight gyms, so it's rather easy to step over, watch a fighter’s energy levels, monitor respiration rates between rounds, max heart rates during sparing if wired, recovery heart rates, hand speed, power and punch volumes, concentration, ability to absorb instructions between rounds, and respond accordingly. Ricci is notorious for wiring up fighters to the fullest extent the team and fighter will allow. Subsequently, acquiring as much information as possible about the fighter’s performance at a given weight. One can argue it's too much info, and hell, maybe it is. Such monitoring does not need to be done daily, and if you can monitor all of this at least once per week, great! Why does this help? Because as a weight-cut coach you can start establishing a weight at which your fighter is performing optimally in camp. Ricci with coaching legends, and former champions of past and present (from left) Mark Henry, Matt Serra, Chris Weidman, Stephen Thompson and Ray Longo. For example, your 212-pound fighter may be killing it at 206 pounds during camp. You like what you see on all markers, the fighter is establishing a superior marriage of strength, power, speed, endurance and recovery. Record all of this to compare and contrast their performance at various weights throughout camp. It will not be our job to independently determine the optimal fighting weight, as the fighter has to provide input on where they believe they feel best, and their skill coaches too will have input on the optimal weight. [29] However, you can offer insight. It’s important for us to remember throughout our work as a weight-cut coach, and/or performance coach, that we are responding to training during camp, not necessarily developing it. Therefore, maybe there are more effective dietary and training protocols for fat loss and weight-cutting than those we are forced to use in a fight camp. That is, what works in a bodybuilding competition as example may be quite effective for fat loss, but it is not compatible with the demands of a fight-camp. We are managing much more than just weight. Training that takes precedent in camp and we must also enhance fight physiology, not just reduce body fat and change body composition like we may see in physique competitions. This is what makes our job so challenging' In summary, the primary reasons for monitoring training during camp, and adjusting diet to training and weight changes, is to establish an optimal weight at which you and the team feel best suits your fighter on fight night. 6) Sleep – As we address vital topics in this book, it’s possible to feel that one particular issue may have greater significance than another. All of the above are of extreme importance, but arguably, sleep may be the most influential determinant of whether anything we discussed thus far will work. As far as sleep and recovery, for the sake of brevity, we will confidently make this statement: your fighter just ain’t going to enhance performance without sufficient rest. Moreover, research shows the risk of injury is 1.7 times greater in athletes who sleep less than eight hours (see infographic). For this reason alone, it can’t be emphasized enough. First, we will emphasize the role of sleep as a part of our weight-cut. Along with losing maximum recovery capacity, hindered performance, and increased injury risk, sleep restriction can significantly impair fat-burning, and the fighter’s ability to preserve lean tissue, especially with caloric restriction and high-training volumes. A highly relevant study by Dr. Arlet V. Nedeltcheva investigated the effects of sleep restriction, and the effects of a reduced calorie diet on the loss of adiposity. They found that sleep curtailment decreased the fraction of weight lost as fat by 55 percent (1.4 vs. 0.6 kg with 8.5 vs. 5.5-h sleep opportunity, P = 0.043) and increased the loss of fat-free body mass by 60 percent (1.5 vs. 2.4 kg, P = 0.002). [30] This was accompanied by markers of enhanced neuroendocrine adaptation to caloric restriction, increased hunger, and a shift in relative substrate utilization towards oxidation of less fat. By scientific standards, or any standards for that matter, these numbers are huge. Furthermore, this was only a 14-day intervention, so one can rationally conclude the effects on fat-loss over six to eight weeks of a sleep-restricted camp would border on hazardous. Chris Algieri in the midst of the weight-cut process This of course is one cited study - we are not providing you with Pub-Meds entire archives at any point throughout this book. However, there is a plethora of data supporting the negative effects of sleep deprivation on performance and all biomarkers. Yet, the relevance in Nedeltcheva’s study is the caloric restriction. Mind you, the participants in the study were not as physically active as our fighters. The question is how much sleep is a good nightly amount for a fighter? Well that is hard to say, but it does appear eight hours is the absolute minimum. Don’t let your fighters tell you what they can get away with - we are not interested in that. As stated earlier, we are not here to tempt the weight-cut process. We are here to maximize it! Some data also supports napping. Heidi R. Thornton investigated the effects of a two-week, high intensity, training camp on sleep activity for professional rugby athletes. In short, they found that while sleep quality and quantity may be compromised during training camps, daytime naps are beneficial for athletes, due to their known benefits and without being detrimental to night time sleep. So, if time for napping is available to your fighter, certainly present them with the idea of doing so. While fighters are working hard in camp, we would assume sleep is easy to initiate and sustain. But some fighters struggle to sleep well during camp. This can be due to a host of factors, such as nerves, sympathetic dominance, dehydration, or other variables. The mechanisms of sleep are quite complex, so much so that it’s a wonder how anyone accomplishes it. There are tools available that potentially measure sleep quality, but the efficacy of wearable technology for monitoring sleep durations is still debatable. Detecting rapid eye movement (REM) sleep with a worn device, or app, is virtually impossible without polysomnography. [31] This type of study records your brain waves, blood oxygen levels, heart rate, breathing, as well as eye and leg movements, during sleep. It requires the placement of electrodes on your head and is best performed in a clinic overnight. The research gold standard is called an actigraph, and it can cost over $1000. Therefore, there are scores of sleep surveys available to help you and your athlete reasonably track sleep. We mentioned biomarkers earlier, so if you have the ability to use them it is worth it, because they not only provide insight on the effects of over-training, and nutritional deficiencies, but also the consequences of sleep deprivation during camp. It is sensible to conclude that enhanced performance and effective weigh-cutting practices are as reliant on sleep as they are on training and nutrition. The brain washes itself clean, and neurotransmitters are recycled during sleep. The body requires a great deal of sleep durations to resynthesize energy substrates, and repair skeletal muscle. Restrictions on optimal sleep durations can not only lead to using less fat during sleep, but perhaps impaired capacity to burn fats in the waking hours, and reduced ability for preserving lean tissue. While sleeping, our fighters can stabilize the hormones that both enhance recovery and optimize metabolism for using fats effectively. Meaning, sleep must be given the same detailed attention that is afforded to training and nutrition. To wrap it all up, there will be a lot of work that comes at the end of a camp. Hopefully, managing all the variables of scheduling, training, weight, nutrition, fluids, and sleep provides insight into much of what we can do to help our fighters during camp. We have offered a basic framework here to help you facilitate a strategic approach to your camp and weight-cut management. As a result, you will foster your fighter’s ability to perform near, or at, optimal levels throughout camp, as well as enhance their skill acquisition, and arrive at fight-week within a range of about four to six percent of scale weight. Going back to the aforementioned 212-pound fighter at the start of camp, we would like to see that designated middleweight weigh somewhere in the range of 196, to 198 pounds on the Monday before a Saturday night fight. Along with being at the desired levels of hydration and body fat percentage of which we calculated earlier. If we do arrive at such numbers, we are set for a smooth cut. If you are working with fighters on cut strategies for the first time, please keep in mind that a considerable number of factors are out of our control during camps. At times, skill coaches may object to some of what you wish to do. There may be injuries along the way that change training volumes, caloric requirements, rate of weight loss, unforeseen rest days, or a week where your fighter is gone for promotion. Even basic life occurrences like the flu, family matters, trash talking from opponents, scores of people getting in your fighter’s ear, USADA waking them up at 5:30 am, or other weight-cut coaches sending them unsolicited texts can become hurdles to cross during a camp. For a brief moment, you may wonder why the hell you’re doing this. Don’t be discouraged by it, just push your plans forward to the best of your ability. This is a tough game, but staying prepared, maintaining protocols, and being open to adjustments can remedy so much of these setbacks. [32] Chapter 5: Cut/Fight-Week Where we arrive on cut/fight-week is contingent upon whether we were able to put in place the necessary protocols. If so, this should not be a week full of alarmism, desperate measures, and questionable tactics. No one wants to resort to scenarios where we are left carrying our fighter to the scale. The hyperbole -- while it may sound extreme -- does have its roots in much of what we have seen through the years. As the cut-coach, you have been preparing for this week since camp started. Much of the worst-case scenarios will be avoided if your fighter and team were both receptive to your strategy and, made an effort to adhere to these strategies as closely as possible. Despite all the previous work, for professional fighters, this very well could be the busiest week of the camp. They will have fans around them, interviews and press conferences, potentially an appearance with their sponsors, photoshoots, meetings with their manager, and so forth. Accordingly, this further emphasizes why we need an early start to the cutting process, and if we are on point with our weight, traversing through these events will not be a problem. There are so many differing strategies during cut-week amongst fighters, skill coaches, strength coaches, nutritionists, and so on, and some of these practices are not always easy to change. Nevertheless, your input as the cut-coach through camp will be considered in the final week. Therefore, it is tough for us to project exactly what you may be able to do during fight week. However, we will need to know what to monitor, and will need to look at the options available for governing the final procedures. This all assumes your fighter is within a good striking distance of the designated scale weight. If not, what we have discussed is possible if more than the desired weight needs to be lost; however it will need to be done to the extreme. This is exactly what we do not want, as it is already difficult to preserve all of the improvements in performance and skill acquired in camp when the cut runs smoothly. We can confidently state that an extreme cut during cut/fight-week can threaten the entire camp’s efforts, especially without a precise rehydration and refueling protocol afterwards. So once again, never tempt physiology - optimize it. If the cutting aspect of camp was a success, where are we come fight-week? On page 13, we provided a potential fat cut before camp, in the range of 14 pounds for a middleweight weighing 212 pounds. While conservative, a loss of 2.5 pounds of lean tissue is unavoidable, because some muscle will always be lost during the cut. There was additional loss that puts our middleweight (who’s allowed to weigh one pound over the 185-pound limit since this is not a title fight) at about 195.5 pounds for cut/fight-week. If we could land a fighter at this weight on the Monday before a Friday weigh-in, pat yourself on the back - since we have not yet even considered a potential drop in carbohydrate intake and its associated water loss. Nevertheless, we are only about five percent above scale weight with a nine-pound water cut remaining over four days. While one may think this an exorbitant amount of weight to lose in four days, we’ve seen it done in four hours. That’s the extreme we desire to prevent with our long-term weight cut strategy. [33] We have mentioned earlier the importance of keeping fluid intake high during camp, measuring pre and post weight from training sessions, and even having a fighter potentially hit the sauna or steam one or two nights a week, so we can see how easily your fighter is turning over water throughout camp. If you have a fighter who is easily losing five to six pounds per training session, particularly if they are a 170-pound fighter or below, you can bet whether you decide to use a hot tub, Epsom salt baths, towel wraps, or sweet sweat, that they are likely to release 10 or even 12 pounds quite easily. Taking out water and electrolytes in large volumes is not an ultimate practice, but these are the two most quickly released and refundable components of the cut. Having to drop two to three pounds of fat, chip away further at lean tissue, and cut your carbs down to a spinach leaf from Monday to Friday of fight-week poses far more health and performance limitations than the release of five or six percent body water. During the writing of this book Ricci was working with a professional boxer by the name of Danny Gonzalez. Gonzalez fights at junior welterweight, which is between 140 and 141 pounds. Gonzalez, when in the range of 156 pounds, often turns over six pounds in a training session. Yet, to his dismay at times, immediately puts that weight back on, because of his excellent dietary and hydration practices. This is exactly the desired effect we are trying to achieve. The immediate and effective release of fluids, and then an immediate and effective re-absorption and distribution of water, electrolytes and glycogen. In an extensive conversation with Dr. Corey Peacock, co-founder of the Fight Science Institute (FSI), and strength coach for Florida’s Hard Knocks 365, Dr. Peacock discussed how the humid temperatures of Florida force Team 365 fighters to sweat excessively, and effectively turn over high water/sweat volume every training session. Dr. Peacock has found come fight-week, these fighters already turnover enough fluid to drop sufficient water volumes for the scale and do so without excessive water loading strategies. This brings to light a point worthy of consideration, the fact that we must keep climate and training environments in consideration. Is acclimatization’s increased propensity to cause sweat, due to increased sweat gland efficiency, or via dilation of pores? We are not sure and while we cannot substantiate, through a large body of research, that we can significantly improve the ability to sweat and release water, we do know that sweat glands can release greater amounts of sweat over time. Therefore, we want to perfect water/sweat release during camp and improve the body’s ability to quickly replenish all that is lost through sweat. This is a mini-cut procedure if you will, rehearsed throughout camp. We do not wish to learn the potential volume of fluid our fighter can release the week of the fight. Our point is, all that what we do during camp will dictate what needs to be done on cut-week. Let’s say our middleweight is still 205 pounds. A 20-pound water drop would be nearly 10 percent of weight. [34] This means that fight-week mornings may still need to include low-intensity cardio to continue removing extra fat. Metabolically they probably can, particularly if forced to be on nearly zero carbohydrates, but they will commensurately lose some muscle. In addition to this, there will be occurrences like drilling, some striking sessions, media, and potentially long water drop sessions consisting of all we mentioned. Saunas, hot baths, hot tubs, Sweet Sweat cream, and/or shadow boxing in saunas. These actions further tax the fighter mentally and physically. Yet with proper preparation, the water drop should be quite passive. Accordingly, we cannot assign an exact procedure you will need to perform during cut-week, but we will list what can be monitored to help navigate your fighter to the scale What to Monitor and Manage Morning to Weigh-In 1) Weight and Body Fat - Step one is to calculate weight, check body fat percent and check hydration status daily. If you have data from previous cuts with your fighter, compare and contrast this with your current numbers come fight week. Based on this, determine if you can effectively make the weight for the Friday weigh-in by way of water dropping alone. If your 185-pound fighter is in the range of about 12 pounds above scale weight, you probably can make the water drop without concern for losing further any muscle, fat, or a drastic reduction in carbohydrates. As stated, if they are well above the range of 12 percent of scale weight on Monday, their cut will require more active modalities, such as low-intensity cardio once or twice daily, a very limited carb intake, as well as a potentially large cut in calories - which should not be necessary if we land in the aforementioned optimal range on weight cut week. 2) Fluids - Monitor your current fluid intake. We strive to increase fluid intake significantly during camp, and don’t water load by current practices. Earlier, we estimated an attempt for a fighter to consume their total bodyweight in ounces, in water and fluids for metabolism, performance and the replenishment of training turnover. In the case of a 205-pound fighter, this is about one and a half gallons (or slightly over). Therefore, a modest increase up to 256 ounces (two gallons) may be rational but increases of 100 to 200 percent of fluid intake on fight-week alone may not be necessary if all steps were followed. Additionally, extreme water intakes are meant to manipulate hormones -- such as ADH or Aldosterone that regulate fluids and sodium -- usually to down regulate, and that’s fine. However, significantly down regulating through loading does not ensure those hormones may settle at optimal levels come rehydration time. Is the approach of higher fluid intakes throughout camp, and a slight build up to fight week, best? We are not sure, but believe it deserves serious consideration. [35] To reiterate, we are not outright opposed to water-loading in its current practice, (and it may be the best option with fights taken on short notice). However, we believe we will understand more about our fighter’s cutting abilities by working the practice earlier in camp. How much fluid each day you decide to cut, and when you decide to cut it during fight week, is contingent upon how much weight must be lost. We have cut fighters’ fluids as late as 18 to 24 hours before the weigh-in, if they are within a range of five to six percent of scale weight the day before. Especially when we saw four percent turnover in training sessions in camp, and high sweat rates during steam/sauna. If you decide to use baths, creams or saunas, they will likely release five to 6 percent of water easily the night before, and even the morning of weigh-in. We are not supporting that much, but it can be done. Therefore, as long as you can preserve fluid intake, do so. While it requires precision, the shortest amount of time the athlete can spend at scale weight, the better. It would be great if we could say conclusively, cut two liters of water every day from Monday to the scale, but if your fighter is close to weight, they may not need to cut it until the last day or two. The intent of the entire book is to create the best possible scenario, and that would mean no drastic loading, nor any drastic cutting of water a week out. First, we trust your decision making at this point, and as a cut coach, we hope you have some input as many fighters may have traditional practices (some good and bad), in which they do the cut procedures all on their own - no matter how much time you have spent during camp. 3) Foods/Nutrition – It’s safe to say, you will also get as many perspectives as there have been fighters who entered the octagon. First, calories as we stated in the nutrition section of Camp Management, will be contingent upon BMR, activity level and how much weight needs to be dropped at the start of camp. As your fighter loses weight, their BMR will decline, and training derived activity levels should be lower during fight week compared to intense weeks in camp. However, we should not discount the potentially busy schedule of fight weeks at the pro level, and even the nerves associated with these events - some of which may contribute to caloric requirements. Calories are likely to be somewhere around BMR for this week. You will read scores of opinions on how many calories or carbs are required, but the idea that this can be scaled is lunacy. What most rational cut coaches agree on is drastic caloric restriction on fight-week is not necessary. The redistribution of macronutrients usually takes precedence at this time. That is, intentional increases in protein because of its high thermogenic effect and capacity to preserve lean tissue, increased water turnover, and also implementing increased fats, which serve as fuel to navigate through cut-week, while carbohydrates become limited. What does limited mean, regarding carbohydrates? This is a great question. We have seen some fighters make the scale at 300 grams of carbs a day up to a few days before the scale. [36] Yet some weight-cut programs insist fighters go below 50 grams of carbohydrates every day of fight-week until the scale weight is achieved. Our best recommendation is to carefully determine a caloric intake for fight-week based on the remaining amount of fat that may need to be dropped for that week. That number may be below actual BMR at current weight if there is still much to cut, or about BMR with a macronutrient breakdown in the range of 35 percent protein, 35 to 40 percent fats, and 25 percent carbohydrates. The more your fighter needs to lose, the more the carbohydrates will need to be cut. For both the purpose of ongoing weight/fat loss, and decreased water retention associated with glycogen storage; which, as mentioned earlier is in the range of three grams of water for every one gram of stored glycogen. This does not really complicate much. Essentially your fighter is working on proteins, vegetables, some berries, perhaps some avocado, and unsalted nuts in order to make the scale. Yes, something such as asparagus may have a natural diuretic affect and can be emphasized, but this is not likely to be substantive to the fighter who still has much water to drop, and fat to burn. Additionally, you may have read, and or been advised to eliminate sodium. This too becomes a bit tricky, because the complete extrication is not possible, nor advisable. However, if for the week of cut we are consuming lean proteins, vegetables, some berries, plus the mentioned fat sources of unsalted peanuts and avocados, the total sodium intake is likely to be well within ranges of 1000 mg daily or below. This level, compared to the previous intakes during camp in which some electrolyte replenishment drinks containing sodium may have been consumed, is actually quite limited and likely to be low enough to facilitate proper water release. Sodium is the first electrolyte to go, and the natural foods of weight-cut week will lower the levels quite rapidly when coupled with sweating practices. Though, the amount of sodium should still be monitored at this time. On page 40, we provide a list of foods that you may want to acquire for the week, so all is available when needed. It’s probably better to over shop and have more food, water and rehydration liquids than needed. This won’t be a problem because for those who have been around fighting, teammates do a pretty good job of sucking down the extra food. It is important to remember that the cut for women is going to require different points of emphasis, as the capacity for water turnover is likely to be limited compared to their male counterparts. An effective reduction in body fat to the lowest potential levels, without a compromise in performance, will be necessary. With the goal of not lengthening this book another 20 pages, we are going to address the full scope of variables in female weight-cuts in separate writings and video, as to provide the attention it warrants. So please check in with both Daru and Ricci on Instagram, as well as our FSI colleagues Dr. Corey Peacock and Chris Algieri at fightscienceinsitutue.com - as advancing the practice of weight-cutting for women is our priority. [37] 4) Saunas, Hot Tubs, Towels and Baths - As if debating how much water one should take in, consume, and cut, does not cause enough confusion, we are adding more. There are many varying opinions on what the best way is to cut water from your fighter during fight-week. Arguments for a passive cut are highly justified. That is, having your fighter not do any intense activity beyond skill training for the week. The body has just finished a brutal camp, calories are down, body fat is at its lowest levels (hopefully), and there is some dehydration of soft tissues/organs/joints. Being forced to run, do jumping jacks, hit mitts, kick shields and run take-downs, along with immense pressure, may not be optimal. Ergo, this is perfect justification for arguing against any intense active methods of cutting by using saunas, hot tubs, towels, baths, and so on. Nevertheless, the fighter will have drilling that is required by their skill coaches during the week. This is to keep the mind sharp, and keep the nervous system and musculature activated. In essence, this can be part of the water cut and release. Meaning that the required skill work can be part of the active cut. Then, additional water cutting can come from the passive methods in which the fighter can potentially relax, like Epsom salt bath. However, extremely hot baths with temperatures relative to that of Venus is not much of a way to relax. If your fighter is competing on short notice, has a lot of weight to cut (and water alone will not get them to scale weight) then our best assessment is an integration of skill specific activity, with inter-dispersed passive measures. Such examples are the sauna upon wakening, and work with coaches while layered. Contingent upon rate of turnover, another passive method later in the day may be the use of a hot tub, steam with Sweet Sweat, or an Epsom bath. Of course, along with getting their weight, measure water turnover from start of sessions to end, and adjust your fluid intake accordingly. In addition, make ongoing decisions in consult with fighter and coaches, as to the next methods of water pull, if any is needed. 5) Plan When to Land at Scale Weight - One of the most important elements is of course landing at scale weight. It is not uncommon for there to be varying opinions within the camp on this. Weigh-ins often occur from 9 am to 11 am, on a Friday morning, for a Saturday night fight. Ricci & WBO & ISKA World Champion - Chris Algieri Some fighters want to go to bed exactly on weight for a weigh-in, others cut some the morning of weigh-in. Which is right? From a purely physiological perspective, we are not sure. [38] However, our FSI partner Chris Algieri feels the less time you spend exactly at scale weight the better, since it is a very taxing and highly a depleted place for the body to exist. One way to arrive at a consensus is to track water turnover the day before weigh-in. If your fighter is releasing water well as they get closer to their actual scale weight, they can likely go to bed a few pounds up. Also, this is where your measuring tools can come in handy. Such as a refractometer (which we discussed in the beginning of the book), as it measures specific gravity and can provide some insight into whether or not the last few pounds can move relatively easy, or whether it will it be like trying to pull water from a brick. Refractometer You may have detected our optimism on the fighter’s ability to chip away at some fat the last week of the weight-cut. However, it’s not our desire to do as such. A pound or two may be feasible depending upon the size of the fighter, dietary applications and metabolism, but the day before the weigh-in is no time to cast hopes on this. From here on out it’s about cutting water. It is then, that the entire team must decide whether your fighter will go to sleep a few pounds above the scale or go to bed at scale weight. Much will be based on superstition, previous practices, or whomever the fighter listens to most. We assure you, after spending 10 to 12 weeks monitoring a fighter, you will have a good idea on just how much can be dropped that morning, which methods they will need to pull the water, and for how long. This is the whole point of our book: knowing what can be achieved in advance of cut-week. This means making minor adjustments to arrive at weight successfully, and not taking extreme measures to arrive at scale weight, and/or attempting to cut with a physiologically diminished fighter. 6) Fight Week Checklist - A checklist is put together to reduce stress during fight week. More times than not, a fighter and their team will be on the road during fight-week. Although, on rare occasions, a fighter will enter a cage or ring near their hometown. [39] As you get to the higher levels in fight sports, you will be in major cities, so there will not be issues with last minute access to anything you need. However, when traveling internationally, it is not as easy. One must prepare by putting together a list of all the things needed, such as types of food for the week, Sweet Sweat, Epsom salts, cut/sweat suits, carbohydrate powders, drinks, electrolytes and so on. It should also include your field tools. For example, your body-fat device, refractometer, or muscle sounds glycogen sensors. As a cut-coach, putting this list together, and having everything at your disposal, will make navigating all practices much smoother. Of course, much of what you bring will be contingent on how you approach the final cut and your rehydration protocols, so we are not in a position to write out a list for you but provide a sample here to serve as a reminder. Sample Food Checklist for Fight Week Vitargo Three bottles of Pedialyte Four liters of coconut water Four gallons of water Dried dates Sea salt Honey NUUN Six Bananas Three Avocados Two pounds of mixed berries Salted and unsalted nuts (mix 30 percent salted) Four lean protein sources Two pasta salads with vegetables (ideally whole wheat) Dark chocolate Root vegetables (beet salad, sweet potatoes, etc.) Whole peppers Humus/bean dip Pita This list is courtesy of one of Ricci’s favorite teams, Team Spartan, Elias Theodorou. Elias and his coaches, Lachlan Cheng, Ash Raf, Chad Pearson, and Even Boris, are some of the best guys in the game. [40] Cut/Fight-Week Summary Fight-week is a crucial time, and it can easily make or break the cut if all practices are not carefully managed. In addition, a non-compliant fighter, in the preceding weeks leading up to cutweek, could also sink a weight cut ship. A point we have reiterated throughout is this is a book on how to help manage the cut and (if done well) give it the potential to run smoothly. Our goal is to help get your fighter well within striking distance in body fat, preserve as much lean tissue as possible, know hydration levels, plan water drop protocols, decide on when to make the exact scale weight, make checklists and start planning rehydration protocols. If all of this is in place, you will bring your fighter to the scale in the best possible condition afforded by a weight-cut, and in position for an expedient and effective rehydration protocol. Frequent collaborators Chris Weidman (center) and Ray Long0 (second from left) during a weigh-in before working with Ricci. [41] Chapter 6: Rehydration and Refuel We have previously mentioned how certain sections of this book could very well require their own book. Well, rehydration and refueling involves so many details and variables, that it is one of those sections as well. However, we are going to do our best to cover the absolute essentials. The urgency of your fighter’s rehydration and refuel is commensurate with the extent of the water cut. That is, it’s vital for any fighter to start this process the second they are off the scale. Although, fighters with last minute water cuts of greater than 10 percent of bodyweight must do this really well. The effects of a difficult weight-cut can be mitigated, to some extent, by a great rehydration and refueling protocol. However, an excellent weight-cut can go to hell with a terrible rehydration and refueling practices. Either way, the first part of this book emphasized getting the cut right, this part is for the basic principles of preparing a fighter after weigh-ins. There are scores of opinions as to what exactly is most important to ingest after the scale. What is the best mix of electrolytes, fluids, sugars, and so on. As you understand by now, much of this is contingent upon the difficulty of the fighters cut, and the practice leading up to this moment. Nevertheless, objective one: Get back the most refundable nutrients, water and electrolytes back into the body. It is quite common for most cut-coaches to wait two hours before introducing solid foods, and we do think that is a suitable practice, despite the fact that some fighters may be able to ingest solid foods right off the scale. As sodium has been lost to the extreme, along with potassium and magnesium for example, it is a requisite to include them in a rehydration drink. Some options include adding sodium to a rehydration drink - about a gram or use an electrolyte powder such as NUUN. Additionally, adding some sugars, such as a bit of honey to the drink, and a small amount of carbohydrate powder (about 25 grams) can be optimal off the scale. The drink, which can range from about 16 ounces, including water and a mix of Pedialyte and/or coconut water, needs to be ready right off the scale. We also suggest a couple of grams of branch chain amino acids, and about five grams of creatine in the drink as the latter can help facilitate intramuscular water retention. We emphasize again, that you will receive and read scores of opinions on this, so remember, we are providing an infrastructure subject to much modification. However, we feel confident about the first couple of hours being dedicated to fluids and electrolytes, with some light foods such as berries and melon interjected between water and the next primary rehydration drink, which can be consumed an hour off the scale. The second rehydration drink will be comparable, except now with about 40 grams of carbohydrate powder, and 25 grams of whey protein. Protein is shown to further facilitate glycogen re-synthesis. As we are starting the rehydration process, remember that after the first couple of hours of fluids, carb powder, and fruits (which are providing electrolytes too), have a scale ready. Start weighing and see how quickly the retention of these fluids is occurring. [42] Also, be prepared to check urine status when it first occurs, the color concentration, or even have your refractometer ready to see the rate at which rehydration is occurring. Below is a sample drink sequence for two to three hours after weigh-in Post Weigh-in off the scale to: Mix 1 scoop Vitargo, 35 grams CHO, with 8 ounces of Coconut water or 4 ounces of Pedialyte, 4 ounces of water, 1 tablespoon of sea salt, and 2 tablespoons of honey Approximately 20 minutes later: Mix 8 ounces of water, 8 ounces of coconut water, and one pack of NUUN Snack on berries, melon, or orange Another 20 minutes later: Mix 8 ounces of water with 4 ounces of coconut water or 4 ounces of Pedialyte Snack on berries and/or melon One hour off scale: Mix 8 ounces of water, 4 ounces of coconut water, 1 scoop of Vitargo carbohydrate powder (about 35 grams of carbs), 1 scoop whey protein (about 20 grams), 5 grams creatine. Drink it steady, not fast 2 rice cakes with any preserves About 30 to 40 minutes after last meal or 1 hour 40 minutes off scale: Mix 8 ounces of water with 4 ounces of coconut water. Drink it steady 2 rice cakes with preserves, 1 banana Relax and digest for 30 minutes. Take your first weight, and monitor for first urination. If the fighter feels ready about 2 hours off the scale, consider a first meal. On the next page you will find an off the scale walk through by our partner at the Fight Science Institute, and the former WBO junior welterweight and ISKA welterweight champion, Chris Algieri. Here Algieri offers a slightly different strategy within the first hour off the scale: [43] 1 - Fluid and Electrolytes Liquids are important but without the electrolytes your body won’t hold it or put it where it needs to be. I set a time limit here as to not overload the system. I focus on a specific volume of water and sodium amount, then make the fighter wait to allow absorption, and for the system to calibrate. (Example: 1 liter of water and 750 mg sodium and wait 30 minutes). This is to make sure you hold on to what you put back into your body optimally. 2 - Carbohydrates and Protein Once fluid and electrolytes are accounted for, it is time to re-feed the muscle to make sure the gas tank for the fight is full. Muscle Glycogen - stored carbohydrate, which is the preferred energy source for high intensity activity. It is clinically proven that carbs+pro, post workout, substantially increased muscled glycogen re-synthesis. ALWAYS dependending on the athlete/weight class/gender/etc., you want to have a ratio of 2-4:1 of CARBS:PRO. (Example: 70 grams of fast digesting carbohydrates and 25 grams of whey protein isolate. About 20 oz. of viscous fluid) Speed of absorption is of the essence here, so liquid is preferred, as is fast digesting (high glycemic carbohydrates) and fast absorbing protein (hydrolyzed whey isolate). 3 - More Fluid and Electrolytes Once the stomach and GI has settled (based on athlete stomach volume and fluid tolerance), time to return to fluid and electrolytes to assure proper retention. A hydration solution with optimal balance of sugar, sodium and electrolytes to replenish vital fluids, minerals and nutrients. (Example: commercial sports drinks and electrolyte solutions) 4 - Normal* Eating (Normal meaning what the athlete is accustomed to during training camp) Eat normally every 2-3 hours with a carbohydrate-centric approach until bedtime. Continue this approach into fight day. 5 - Carbohydrate and Fluid Pre-Fight The closer you get to contest time, the most important and beneficial nutrients are carbohydrates and fluids. As you get closer to fight time, the more you should focus on carbohydrates, and less on fats and protein. Keep drinking fluids and maintain a urine color that is closer to light straw color. The reasoning behind the fluids and light fruits is because the fighter was restricted in total food volume for a deliberate duration, so they will not be prepared to rush in two bowls of pasta and a 41-ounce porterhouse. However, once we start seeing color come back to our fighter, vascularity starts to show as plasma volume ticks up, we see substantive movement on the scale, increased urine frequency with lower specific gravity, and maybe even get a smile out of the fighter, then we should be ready for some food. Many fighters will have their traditional meals, and they should enjoy it. However, neglect of diet at this point would make no sense. [44] A Burger King whopper and a Slurpee will put in plenty of water, sugar, sodium, fat and carbs, but very little of it will land where it needs to be for optimizing fight performance. We certainly emphasize good carbs, quality protein in moderate amounts, and consuming seven to eight different colored fruits and vegetables from scale to the fight, as this ensures additional fluid volumes, and a large cross-section of electrolytes and nutrients. A primary goal now, it to get the carbohydrates in so that we can expediently replenish blood glucose, liver glycogen (which can range from 75 to 125 grams), and skeletal muscle glycogen stores (likely in the ranges of 400 to 650 grams). We can arbitrarily throw carbs at the fighter in the meals between weigh-in and the fight. However, we use minimum carbohydrate and calorie estimates, while carefully monitoring weight, to help our fighter slowly and methodically replenish themselves. We want to improve muscle and liver glycogen, intramuscular water, and electrolyte distribution while arriving at the predetermined fight-weight established in camp, and make sure everything is where it needs to be as to fuel the fighter into and through the fight. We discussed earlier the general potential of glycogen storage in both liver and skeletal muscle, and they are true estimates. Although, that may be reasonable for the model middleweight we have discussed throughout this book, potentially holding over 100 grams of liver glycogen and 500 grams of skeletal muscle glycogen. While complete depletion is not likely to occur during cut (unless it’s been one of the worst-case scenario cuts we’ve mentioned) considering target numbers for carbohydrate intake, from the time of the first meal to the fight, may be helpful. The earlier carbohydrates we ingested in our rehydration drinks are likely to run through the blood quickly to supply the brain and basal metabolism with some glucose. As well as some potentially directed to glycogen as we ingested about 120 to 140 grams of carbs. Now that we addressed immediate demands, we can think about stacking the liver and skeletal muscle with some glycogen. Is it necessary to target an amount of carbohydrates in grams from the post weigh-in to the cage? Probably not! However, that does not mean it has no potential value. During the final phases of the cut, the diet was very protein-centered. It will now be very carbohydrate-centered. This doesn’t mean removing protein, because protein will help facilitate glycogen storage when ingested with carbohydrates, but maybe now we are in the range of 60 percent carbs, 20 percent protein and 20 percent fats. Therefore, if your fighter has the capacity to ingest generous amounts of food, and the fighter can store in the range of 600 total grams of glycogen as with our middleweight, we can potentially target close to that number from about 1 pm in the afternoon of the weigh-in, until bedtime. This would bring us to about 2400 calories in carbs alone. Of course, some of which will come from fruits and vegetables, with some added protein of about 150 grams and 50 or 60 grams of fat. Meaning a total of over 3000 calories will be consumed. We understand that this is a good deal of food, but the day before the fight may pose the best window for eating, as many fighters find it harder to eat on fight day. [45] A common argument is if your middleweight fighter is targeted, hypothetically, to rehydrate up to 209 pounds, when do you want to be at that weight? Well, probably the night of the weigh-in. Catching up on weight the day of the fight, is not so easy, nor the preferred time to stuff the fighter with food. Remember, if your fighter arrives at the determined fight weight the night of the weigh-ins, they’re likely to drift some overnight. Reloading a few pounds the next day is reasonable, but being 10 pounds in the hole on fight day leads to complete disaster. While these numbers for total calories and carbohydrate grams are a framework, you can assess whether the intake of foods and fluids, up to any point, is working by measuring weight, urination frequency and color, and measuring specific gravity. If you’re well behind target weight early on the night before the fight, well you know the deal: increase the carbs and fluids until more is sticking where it needs to. Our hope is that we wake up close to the desired weight. Some fighters can eat like Henry the XIII on fight day, and others are anxious and have little appetite. Carbohydrate and protein powders come in handy for those with muted appetites on fight day. However, if they can eat, they must! The brain and body will rip through calories on this day and preserving that which we consumed and stored from post weigh-in eating, is imperative. A rational aim on fight day is another 400 to 500 grams of carbohydrates from morning to the fight; with light protein and constant fluids throughout the day. This should help us arrive at, and maintain, our desired fight weight. These are sample meals providing the carbs and calories we discussed for obtaining about 500 grams of carbs, after weigh-in. These sample meals are simply to add context, and don’t need to be followed as far as the food itself. [46] Below is a sample meal sequence from getting off the scale to bedtime: Meal 1 at 12:30 pm, after 9 am weigh-in: 10 ounces of pasta and meatballs, 2 pieces of bread, a large green salad 16 to 20 ounces water 120 grams of carbs total --------------------------------------------------------------------------Meal 2 approximately at 3 pm: Mix 2 scoops Vitargo, 70 grams CHO, with 8 ounces of coconut water, 4 ounces of water, and 25 grams of protein powder 1 banana, and some berries 110 Grams Carbs Total -----------------------------------------------------Take weight Meal 4 at 6:30 pm: Peanut butter and jelly preserves sandwich, 2 big tablespoons of peanut butter, 3 tablespoons of preserves, 2 slices of whole grain bread 1 banana and a 20 ounce water 90 grams carbs total Meal 5 at 9 pm: 10-ounce salmon, a large salad, 2 large servings of yellow squash, large sweet potatoes, 2 slices of bread, and a 20 ounces water 90 grams carbs total Now get them to bed! With rehydration drinks and meals since weigh-in, our fighter has consumed about 540 grams of carbohydrate, or 2160 calories in carbs alone. This is a solid foundation for replenishing a substantive amount of glycogen, electrolytes, water, and nutrients. In our fruits and vegetables thus far, we have included the colors green, orange, red, blue, and yellow. Another color or two and we have covered the prism quite well. [47] Saturday Morning – Fight Day Take weight the morning of the fight. Assuming we are in a good place, weight is on target, and your fighter can eat, here is a sample plan for fight day. Meal 1 - 8 am fight morning: 1 pack of Vitargo, 70 grams CHO, 16 ounces water, and 25 to 30 whey grams of protein 1 Banana 95 grams carbs total ----------------------------------------------------------Meal 2 - Two hours later: Breakfast toast, oatmeal, fruit, some protein, eggs, yogurt, fighter’s choice 20-ounce water 100 grams carbs total ----------------------------------------------------------Take weight and check hydration Meal 3 at approximately 2 pm: Light protein such as 6-ounce salmon, small salad, 1 vegetable serving, and sweet potato 16-ounce water 75 to 80 grams carbs total ----------------------------------------------------------After breakfast and lunch, we will have consumed about 800 grams of carbohydrates or 3200 calories in carbs since weigh-in. This is a really good number for restoring glycogen levels to the best possible extent, and help drive water back into the muscle. With the foods and the supplements ingested, an emphasis on electrolyte replenishment has occurred as well, including Na, K, Mg. Water intake/fluid will be the in range of 264 to 300-ounce base from time of weigh-in, to the afternoon of fight. However, a fighter can drink steady as the fight nears, according to hydration and weight. [48] Here we proposed a last meal listed at 2 pm. That is not the last meal, unless your fighter is first on a card, and fighting exceptionally early, say 5:30 or 6 pm. However, if they are on the main card, they may fight at 10 pm EST at the earliest. In this case, an ongoing strategy is necessary, as we still have many hours before the fight. The drinks, foods, carbohydrates and calorie numbers we provided since the scale were estimates to ensure a solid level of hydration and fuel to this point. How much your fighter drinks and eats in the remaining five to eight hours may have much to do with their preferences. As some like to be heavily fueled within a couple of hours, and others like to go in feeling lighter. With that in mind, having a bit more complex carbs ready, such as white rice and lighter proteins like fish, is advised, if there is time for more solid meals. As we approach the closing hours, light carbohydrate foods take precedent, such as going back to a couple of rice cakes with some preserves. Having berries handy, and a steady fluid intake, should sit us well for the fight to come. As a note, the calorie and carbohydrate intake we recommended and monitored were not just for providing a minimum intake to ensure suitable rehydration and refueling, but to ensure we are on track to hit our fight weight decided in camp. Reckless feeding can lead to going into the fight too heavy, and this can pose problems equal to that of being underweight. The goal is a weight that marries all biomotor abilities to the best capacity. Too heavy, and we may lose endurance and speed, too light, and we may lose strength and power. Where they all exist in balance, is the sweet spot. All that we see here is a framework. Remember, there are so many variables that dictate the success of a rehydration and refueling protocol. This is a fragile process, and we have to do the best we can. A major part of this is carefully monitoring the progress of hydration, weight gain, complexion, mood, and all other facets that matter to the fighter and team. Many weight-cut specialists will swear that their approach is the gold standard. However, the idea that an identical rehydration and refueling protocol will produce an identical physiological response in the same fighter each time they are fighting is lunacy. [49] Chapter 7: Tying it All Together We will end this book the same way we started; by thanking you for taking the time to read it. As stated from page one, our goal was to provide a process of weight-cutting that helps you set up your own system and strategies for navigating your fighter through it all. We acknowledge that this is an imperfect science. Weight-cutting is a fine art that uses scientific principles in a volatile environment. We are well aware that some will read this book and dissect everything we have written. Some will claim they are the only source for a true system. Others will read this and say, “They have made a good point,” and pick up a new way of thinking about this key process in a fight camp. Those responses are fine with us, because the numbers we provided are not perfect, the physiological practices are not perfect, and nutritional protocols and rehydration recommendations are not perfect. In the end, we have thoroughly discussed many of the key facets of weight-cutting and hope you feel informed, are now fully cognizant of many of these variables. In weight-cutting, we are asked to do something antithetical. That is, enhance human performance while restricting the fundamental framework of that which advances it: calories, nutrients and water. However, with the strategies we have provided, this can be done safely and effectively. We are confident in our methods, and are confident that all of you, the future of fight sports, will lead the progression of this always evolving process. We are not sure what measures fight sports, and their respective organizations, will take in the future to manage the practice of weight-cutting. Nevertheless, an understanding of the basic sciences and physiology associated with this practice, and a system for approaching it, will have you prepared regardless. Once again form Phil Daru, Tony Ricci, and our colleagues at the Fight Science Institute, Dr. Corey Peacock and Chris Algieri, thank you! Please stay in contact with us via Instagram where we update our videos regularly. Phil Daru @darustrong Tony Ricci @fightshape_ricci Corey Peacock @drcpeacock Chris Algieri @chris_Algieri [50] About the Authors Phil Daru, FMS, CFSC, ISSA-KMS, FRC Phil Daru has been involved in athletics and martial arts throughout his life. In his adolescent years, Daru gravitated towards impact sports such as football, boxing and wrestling. However, when he reached high school he focused primarily on playing football, which is a way of life for many athletes growing up in South Florida. From his high school football exploits Daru received a scholarship to Alabama State University, where he played strong safety and linebacker. While at Alabama State, he furthered his love of training and learning about how to optimize performance with proper nutrition and program development. Upon graduating with a Bachelor’s degree in sports medicine, Daru would make the transition into a career in MMA. Through his close interaction with the sport, he became entrenched in human physiology, and the bioenergetic demands of fighting. He also grew a deeper understanding of the nutrients needed to optimize performance, manage fatigue, and recover properly from training. With this developed understanding of the fitness side of the fight game, he started working with other athletes and combatants to improve their strength and conditioning. Through these experiences, Daru would formulate the framework of the programs he uses today. His dedication to the craft showed early in the process, as at 22-years-old he won the award for best strength and conditioning coach at the Florida MMA Awards in 2012. Despite not even being 30-years-old yet, Daru has worked with over 100 professional fighters. 8 whom have been champions in major promotions. Some of those fighters include Dustin Poirier, Tecia Torres, Valerie LeTourneau, Tyron Woodley, “King Mo” Lawal, Colby Covingting, Walt Harris, Alexey Oliynyk and Joanna Jędrzejczyk. Furthermore, he has had the privilege of working with, and befriending, some of the best coaches in the business. [51] Tony Ricci, DSc, MS, FISSN, CSCS, PES, CNS, CDN Tony Ricci is a highly accredited athletic performance specialist, and performance nutritionist. He has a lifetime of practice and academic study dedicated to health, fitness, nutrition, and sports science. At the age of 11, he began lifting weights and practicing martial arts. He is a former Mr. Eastern USA Bodybuilding Champion and holds black belts in multiple combat disciplines. For the better part of 30 years he has trained, coached, and consulted thousands with varied objectives; ranging from weight loss and improved fitness, to Olympic competition. For the last 23 years, his efforts have focused exclusively on fight physiology and performance. Ricci has worked with scores of Division I collegiate wrestlers, and kickboxing/boxing champions like Bobby Campbell, Daria Albers, Chris Algieri and Heather Hardy. In MMA Ricci has been fortunate to work with Ryan LaFlare, Dennis Bermudez, Elias Theodouro, Gian Villante, Aljamain Sterling, Liam McGeary, Marcos Galvao, and Chris Weidman. Ricci also works as a sports science consultant for Team Serra-Longo. Away from his coaching endeavors, Ricci is an Associate Professor at Long Island University, teaching undergraduate and graduate courses in Sports Nutrition, Exercise Science, Nutritional Biochemistry, and Strength and Conditioning. In addition, he is the founder of Fight Shape International, a multi discipline health/wellness and performance enhancement company. Ricci is a Fellow of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, serves on the ISSN Advisory Board, as well as the scientific advisory board for Dymatize Nutrition, and proudly the President of the Fight Science Institute. Ricci holds Master’s degrees in human nutrition, exercise physiology and has done doctoral work in Health Sciences. He is currently completing a second Doctorate in Sports Psychology & Performance through Western States University. He is a certified Performance Enhancement Specialist, Strength & Conditioning Specialist, and is a board and state licensed/certified nutritionist. [52] Special Thanks to Our Colleagues at the Fight Science Institute (FSI) Chris Algieri, Fight Science Institute Director of Nutrition and Bioenergetics Chris Algieri is a former WBO junior welterweight champion, ISKA welterweight kickboxing champion and WKA super welterweight kickboxing champion during an over 13-year career. He has been featured on HBO pay-per-views, HBO Boxing After Dark, NBC Boxing, Showtime Boxing, PBC on Spike and ESPN Friday Night Fights. The New York native has also competed at historic venues such as Madison Square Garden, Barclay’s Center, Mohegan Sun Arena, and the Cotai Arena in Macau, China. Algieri graduated from Stony Brook University with a degree in health care science and went on to earn his Master’s from the New York Institute of Technology in Clinical Nutrition. He is certified by the International Society of Sports Nutrition, and regularly presents at national conferences around the United States. When not continuing his boxing pursuits, Algieri also works as a performance nutritionist with some of the best fighters in boxing and MMA. Along with that, he is also a nutrition consultant for the athletic department of his alma mater, Stony Brook University, overseeing the needs for 400 athletes competing in 15 different sports. Algieri’s unrelenting passion for nutrition and human performance is rooted in his intense love for sport and competition. Following that passion, Algieri is willing to share his education and competitive experience with others, in order to maximize the potential of each and every athlete with whom he has the honor to work with. [53] Dr. Corey Peacock, Fight Science Institute Director of Sports Science, Ph.D., CSCS, CISSN, FRCms Dr. Corey Peacock is currently serving as the Head Performance Coach and Sports Scientist at Peacock Performance Inc. In this role, he is responsible for providing strength and conditioning, physiological analysis, and injury prevention methodologies for some of the world’s elite combat athletes. Including fighters from Florida’s Hard Knocks 365 gym, such as Anthony Johnson, Volkan Oezdemir, Stefan Struve, and Kamara Usman. He performed this role previously with another notable MMA gym in the state, the Blackzilians. Prior to MMA, Dr. Peacock spent his time as a strength and conditioning coach at the collegiate level, where he focused his application on football. A former collegiate football player, Dr. Peacock graduated from Kent State University with a Ph.D. in exercise physiology. Along with his work in MMA he also trains many professionals from the NFL, NHL, and NCAA football, and is regarded as one of the top performance coaches, and sports scientists in South Florida. Along with coaching, Dr. Peacock serves as an associate professor at Nova Southeastern University. As a researcher, he has contributed multiple peer-reviewed publications, integrating the fields of exercise physiology, athletic performance, and supplementation. Dr. Peacock is a performance consultant for both The International Society of Sports Nutrition and The Advanced Coaching Academy. [54] Example Charts and Info Graphics Data graphics provided by a BodyMetrix Ultrasound MuscleSounds glycogen technology [55] SAMPLE CAMP CHECKLISTS [56] Assessment Name: _____________________________ DOB: ______________ Age: ______ Gender: _________ Fight Discipline: ____________________ Company/Organization: ___________________________ 1. Initial Assessment Weight Cut History: What discipline is your fighter in? When did they start? Amateur? Professional? How many times have they had to weight cut in previous fights (if any)? Difficult weight cuts? Did you meet your goal? How did you feel before the fight? After? __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________ Scale Weight and Class: Current weight? What class do you plan on fighting in? Have you made this weight in the past? If so, how many times? Easy? Difficult? __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ Max Weight: In the past, what weight did you begin at? Do you train between fights to keep your max weight consistent? __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ Dietary Practices: What type of nutritional practices did you have in other camps? What type of diet do you keep outside of camp? __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ [57] Starting Data Assessment Camp Opening: Fighter ____________________________ Fight Date______________ Camp Week _______________ Date _____________ Height: ___ ‘___” Current Weight: _____ lbs. Lean Muscle Mass: _______lbs. Body Fat %: ___ Total Body Water (TBW): ___________ Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR): _________ Resting Heart Rate (RHR): __________ Blood Pressure (BP): ____/___ Heart Rate Variability: ___________________________ Measurements: Neck: ____in. Chest: _____in. Upper Arm:____ in. Waistline: _____in. Thigh: ______in. Calf General Biomarkers: Testosterone levels: __________________ Free testosterone: ____________________ Cortisol levels: ________________________ Cholesterol: __________________________ Triacylglycerol levels: ________________ Blood Glucose levels: _________________ Sodium levels: ________________________ Potassium: ___________________________ [58] Weekly Data Tracking Fighter ____________________ Camp Week _________________ Dates _______________ Height: ___ ‘___”Current Weight: ______ lbs. Lean Muscle Mass: _______ lbs. Body Fat %: ___ Total Body Water (TBW): _______________ Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR): _________ Resting Heart Rate (RHR): _____ Blood Pressure (BP): ____/___ Heart Rate Variability: _____ Max Training Heart Rates ___________________ Recovery Training Heart Rates 1 min _____________________ Measurements: Neck: ____in. Chest: _____in. Upper Arm:____ in. Waistline: _____in. Thigh: ______in. Calf General Biomarkers: Testosterone levels: _________________ Free testosterone: ___________________ Cortisol levels: ______________________ Cholesterol: _________________________ Triacylglycerol levels: _________________ Blood Glucose levels: ________________ Sodium levels: _________________ Potassium: ____________________ [59] Camp Management Training Schedule: Camp Week _______ Skill Set 1 Time Skill Set 2 Time Skill Set 3 Time Date _____________ Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Training Costs: Camp Week ______ Water Lost Each Session Water Replaced Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday [60] Estimated Calories Burned Weekly Macronutrient Breakdown Macronutrient Breakdown Total Calories Percentage Grams Calories Protein Carbohydrate Fat Nutrition and Timing Meals Time of Meals Fluid Intake [61] Nutritional Aims Sleep Day Day Hours of Sleep (hrs) Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday [62] References 1) Trexler et al. Metabolic adaptation to weight loss: implications for the athlete Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 2014, 11:7 2) Jeukendrup, A. E., & Gleeson, M. (2010). Sport nutrition: An introduction to energy production and performance. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. 3) Ichinose-Kuwahara, T., Inoue, Y., Iseki, Y., Hara, S., Ogura, Y., & Kondo, N. (2010). Experimental Physiology -Research Paper: Sex differences in the effects of physical training on sweat gland responses during a graded exercise. Experimental Physiology, 95(10), 1026-1032. doi:10.1113/expphysiol.2010.053710 4) Schoenfeld, B. J., Aragon, A. A., Moon, J., Krieger, J. W., & Tiryaki-Sonmez, G. (2016). Comparison of amplitude-mode ultrasound versus air displacement plethysmography for assessing body composition changes following participation in a structured weight-loss programme in women. Clinical Physiology and Functional Imaging, 37(6), 663-668. doi:10.1111/cpf.12355 5) Huovinen, H. T., Hulmi, J. J., Isolehto, J., Kyröläinen, H., Puurtinen, R., Karila, T., Mero, A. A. (2015). Body Composition and Power Performance Improved After Weight Reduction in Male Athletes Without Hampering Hormonal Balance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29(1), 29-36. doi:10.1519/jsc.0000000000000619 6) Langan-Evans, C., Close, G. L., & Morton, J. P. (2011). Making Weight in Combat Sports. Strength and Conditioning Journal,33(6), 25-39. doi:10.1519/ssc.0b013e318231bb64 7) Campbell, B., Kreider, R. B., Ziegenfuss, T., Bounty, P. L., Roberts, M., Burke, D., . . . Antonio, J. (2007). International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: Protein and exercise. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition,4(1), 8. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-4-8 8) Hector, A. J., & Phillips, S. M. (2018). Protein Recommendations for Weight Loss in Elite Athletes: A Focus on Body Composition and Performance. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism,1-8. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.2017-0273 9) Bounty, P. L., Campbell, B. I., Galvan, E., Cooke, M., & Antonio, J. (2011). Strength and Conditioning Considerations for Mixed Martial Arts. Strength and Conditioning Journal,33(1), 56-67. doi:10.1519/ssc.0b013e3182044304 10) Milewski, M. D., Skaggs, D. L., Bishop, G. A., Pace, J. L., Ibrahim, D. A., Wren, T. A., & Barzdukas, A. (2014). Chronic Lack of Sleep is Associated With Increased Sports Injuries in Adolescent Athletes. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics,34(2), 129-133. doi:10.1097/bpo.0000000000000151 11) Nedeltcheva, A. V., MD. (2010). Insufficient sleep undermines dietary efforts to reduce adiposity. Ann Intern Med,1-14. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-153-7-201010050-00006 12) Thornton, H. R., Duthie, G. M., Pitchford, N. W., Delaney, J. A., Benton, D. T., & Dascombe, B. J. (2017). Effects of a 2-Week High-Intensity Training Camp on Sleep Activity of Professional Rugby League Athletes. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance,12(7), 928-933. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2016-0414 [63]