How Advertising Works:

A Planning Model

. . + putting it all together.

Richard Vaughn

The adverlistng industry has long been

chalJenged to explain how advertising

worka. That it does work is not an

issue. But liow it worts and why it

works are critical concerns still unrescEvedI f we had a proven theory of advertising effectiveness it would help in

strategy planning, response measure*

meat and safes prediction. We have no

such theory. Empirical " p r o o f " is

scattered in numerous company and

agency files. The possibility for a scientifiKllly-deriYed model of advertising

seems remote.

Despite this difficulty, increasing

costs and competitiveness require lhat

we iliake an effort to comprehensively

address how advertising works, The

subject is important, complex aad dynamic. It is important to manufacturers

as a marketing expensed rami investment, and to advertising agencies as a

product of tlieir creative energies, i t is

comple* because communication theories ate not unified, and evidence is

scarce. And, fma[!y, it tS dynamic be-

cause recent marketplace experience

has provoked newer, controversial explanations.

Advertising is unlike the direct communication between two people which

involves a give-and-take experience. It

is a one way exthange that is impersonal in formal. To compensate, advertising must oflen make greater use

of both rational and emotional devices

to have an effect- people can selectively notice or avoid, accept or reject,

remember c-r forget the experience and

thereby confound the best of advertising pjaas.

To understand how advertising

works, it's necessary io explore the

possibilities people have for lhinJkirt£,

feeing and behaving toward, the various products and services in their

lives. This isn't easy because we are

all capable of being logical and illogical,

objective aad subjective, obvious and

subtle simultaneously. Everything considered, it's not surprising thai a unified theory of advertising effectiveness

has eluded us for so long.

This paper presents an overview that

sketches, rathef thsn details where we

are, where we have been, and where

we may be going in advertising effectiveness theory. To accomplish this

tjisk, the Fallowjng outiitle w i l l be pur

Sued;

* Traditional

Advertising

Theories

prevalent ill the I95r>°s are reviewed

as background,

* Consumer Behavior Models representing the 1960's trend toward comprehensive, sequential theories are

discussed.

• Recent Developments in high/low involvement and right/left brain theories are introduced.

• An FCB Mvdei is presented which

organizes advertising effectiveness

- theory for strategy planning.

There is a tendency for advertisers

to be defensive about this subject.

Frankly, one theory seems as plausible

Copyright g> Fpote, Cone &, Bd.Jing. C o m m u m

cm inn:;, I n c . , 1379. Reprinted by p e r n m i i o n . Edl f w i . i l changes in bracket*.

27

VXA124 6218

V X A 1 2 4 62JS

http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lsw36b00/pdf

USX271 773

Jtturrjul vf Advertising

Research

as> another in certain situations, and the

urns and c o n s often result in a stalemale. This paper, however, is asieflive

and positive. This is so for two r e a s o n s :

(3) To establish key points and

[2> T o stimulate further discussion.

The greater purpose, of c o u r s e , is a

better understanding of strategy options and w a y s uf planning, creating^

executing and testing more effective

advertising. T h e mew FCB model is &

major step in that direction.

Traditional Theories

Four traditional theories of &dvejijsing effectiveness have been prominent

in [rrarkcting:

• Economic—a rational consumer who

Consciously c o n s i d e r s f u n c t i o n a l

tust-utility information in a. purchase

derision.

• Responsive—a

habitual Consumer

c o n d i t i o n e d to thoughtlessly buy

through rote, stimulus-respoasc

teaming.

• Psychological—an

unpredictable

c o n s u m e r w h o buys compulsively

under (he frdluerice of unconscious

thoughts and indirect emotions.

• Social—a compliant Consumer who

continually adjusts purchases to satisfy cultural dad group n e e d s for

confonnityWhile these theories have had proponents who defended them as sole

e x p l a n a t i o n s of c o a s u m e r b e h a v i o r ,

most marketers now consider them at

best only partial explanations These

theories -were most topical in t h e 1950's

and Can be summarized as follows:

• Economic theory says c o n s u m e r s act

in their o w n financial spjf-inEeresi.

They look for maximum utility at the

lowest Cost. Rational, meitiudicai

calculation is pre-supposed, s o price

demand equations are used t o calculate aggregate consumer behavior.

Consumers most r a v e functional inform a lion To make a decision. This

old, much-revered theory most often

applies t o commodity items- It is

highly respected by economic forecasters and is the only Iheory widely

publicized by U . S . government regulator y agencies.

• Responsive

theory

tells u s c o n sumers are lazy and want to b u y

with minimum effort. They develop

habits through stimulus-response

learning. T h e process LS non-rational

and a u t o m a t i c as repetition fjoildi

and then reinforces buying activity

for routine p r o d u c t s . Information

serves a remit) derfexpoBurfi, rather

than thoughtful, purpose.

• Psychatogtcal

theory explains consumer behavior a s ego involvement:

the personality must be defended o r

promoted. This is essentially unpredictable, undeliberate and latent a s

psychic energy flows between the id,

ego and super-ego. Implicit p r o d u c t

attitudes arc MOre important than

functional benefits for the selective

products that touch people s o d e e p ly. This " h i d d e n p e r s u a d e r " t h e o r y

is discussed most by militant Constimerisis.

• Social theory describes Consumers

as basically imitative. People vy&tch

what others buy and comply/adjust

to get along o r be inconspicuous. It'4

an e m o t i o n a l , i n s e c u r e b e h a v i o r .

Group role, prestige, status and vanity c o n c e r n s are involved. Opinion

leaders and wurd-of-mouth communication are important for [he visjblc

products affected.

Which theory is right? They all h a v e

some truth. Economic motives d o m i nate m u c h conEume* behavior, especially on expensive products and those

wiih highly functional benefits. B u t f l e

spOnsive buying also prevails; many

r o u t i n e Llems r e q u i r e l i t t l e or tto

thought, and purchase habits, once established, can serve indefinitely, Psychological issues complicate our understanding because many items can

have " s y m b o l i c " overtones. T h e same

is true of Snrlal motives since n u m e r

q u s p r o d u c t s h a v e public m e a n i n g .

T h u s , at various limes and for different

pfwJuct3, each t h e o r y might play a part

in c o n s i d e r a t i o n , p u r c h a s e and consumption behavior.

While these theories have enough

face validity [o make them interesting.

they hick, the specificity to make them

practical. Also, which theory to use in

a situation, and how t o blend it with

other theories a r e constant and frustrating problems,. Time and the efforts

of Consumer theorists have moved bey o n d these s i m p l e r e x p l a n a t i o n s t o

more d y n a m i c n o t i o n s of how c o n sumera respond t o advertising.

Consumer Behavior Models

Many c o n s u m e r b e h a v i o r m o d e l s

were developed in the early I960's r

T h e y took ^ variety of forms but moat

were p a t t e r n e d after Lavjdge and Steiner'<; " H i e r a r c h y of Effects" model in

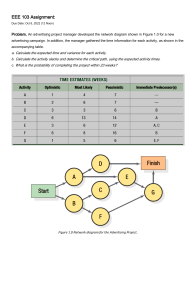

1961 l a c e Figure i j .

This model p r o p o s e d that Consumer

p u r c h a s e of a product occurred via a

sequential h i e r a r c h y of events from

awareness through k n o w l e d g e liking,

preference, and conviction. It was a

major step toward integrating the implications of the Economic, Responsive, Psychological and Social theories.

In principle at least, rational c o n c e r n s

could co-exist wirh habituation, e g o

involvement and conformity motives.

Although research has been Unable t o

verify the model, it has been concep-

hrgure 1

PURCHASE

*

CONVICTION

4

PREFERENCE

•

LIKING

*.

KNOWLEDGE

*

AWARENESS

28

VXA124 6219

VXA124 6219

http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lsw36b00/pdf

USX271 774

Volume 20, Number 5, October 19tiO

rnally useful and, because of its common sense qualities, remains today the

intuitive, implicit model accepted by

most marketing managers.

Andreasan U9&3). Nicosia (196*)

aiid Enfccl-Kollal-Elatkweli (L967) proposed valiant models, but the ultimate

in thoronehrcsa and complexity appeared in 1969 with publication of

Howard & Sheth's The Theory of Buyer Behavior. The model involved 35-40

variables grouped under input, perception, learning and output categories.

Several research efforts validated the

basic form (if the model, bill the predictive pcWL-r was low because operational measures for many of the variables were weak.

Despite ttielr derail, these secondg en e ration models remedied defects in

the basic hierarchy model:

* Consumers might proceed through

the sequence imperfectly (stop/start,

make mistakes!

* Fsedback would allow later events

to influence earlier activities

* And finally, consumers cuuld skip

the process entirely end behave "illogically".

bi a return (Q simplification, the following summary adoption process

model appeared in 197) (Robertson). It

included the main features of earlier

models [see Figure 1).

This modified '•hierarchy 1 ' model

proposed that some consumers, under

some conditions, for some products,

might follow a sequential path. The

dotted lines [In Figure 2] arc feedbacks

that can alter outcomes, Other decision

patterns on the right track consumers

as they violate the formal seqUetlce of

the hierarchy. Thus, consumers can

learn from previous experience and

swerve from trie Hwarenexs-(o-(jmchase pattern,

_, This scheme preserved the LEARttFgEL-DO sequence of mast hierarchy

modeta but made it more flexible. It

also heified explain purchase behavior

without the presence of measurable

product knowledge or attitude formation. Shortly after the arrival of this

model, however, other hypotheses appeared.

Figure 2

ADOPTION

4

TRIAL

*

LEGITIMATION

*••••

I

I

-

^—

*

ATTITUDE

+

COMPREHENSION —»•

4

AWARENESS

Recent Developments

The new theories are not fliodch so

much as explanations for conflicting

results from consumer research. They

are respectively, Consumer Involvement and Brain Specialization. They

bsve been introduced to explain why

consumers are interested in some purchase activities more than olhers and

how consumers perceive different messages during purchase consideration.

Briefly, Consumer Invotvettxent suggest? a eootinuum of consumer interest

in products and services. On the high

Aide are those that are important in

money cost, ego support, social value

or newness; they involve more risk,

require paying more attention to the

decision and demand greater use of

information. Low involvemem decisions are at the other extreme; they

arouse little consumer interest or information handling because the risk is

small and effort can be reduced accordingly.

It's hard tu define this concept because involvement can include consumption as welt as purchase situations. Basically, the money, time,

complexity and effort involved in buy-

—*• —»•

ing and using products demand that the

consumer make value judgements.

Some decisions are important enough

Richard Vaughn joined foots, C&ti£ &

Bfldmg/Honig in Los Atigeies as director

or research in 1978. From L963 to 1977

he held various marketing and research

'positions With Button Farina and its

subsidiary, Van Camp Sea Food. He Is

a speaker 00 advertising and research

and has served as a member of the

editorial review hoard of ihttjeurnai of

Marketing. Vaughn majored tn philosophy and literature at Glendale and Occidental Culltges aad UCLA,

29

VXA124 6220

http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lsw36b00/pdf

Journal

of Advertising

Research

to gel a lot Qf effort, others are not. As

the slakes rise, mora attention must be

given to the decision to avoid mailing

a bad buy. The lower-risk product lias

a lighter penalty for a mistake, and less

anxiety about tttt outcome. The implication: involvement level affects receprivity to advertising.

Brain Specialization proposes that

anatomical separation of the cerebral

hemispheres of the brain leads to specialized perception Of messages. The left

side is relatively more capable of handling linear logic, language and analysis—in short, the cognitive (thinking)

function. The right side is more iniuifivc, visual and engages in synthesis —

the affective (feeling) function. The implication: adveniajriB response will

vary depending uppn the thinking or

feeling communication task involved.

This subject is quite topical, and

enthusiasm for it is producing considerable marketing speculation. Tit*

physiological evidence is limited and

there is no empirical support for it fn

a marketing context. However, it's QOt

necessary ro endorse right/left brain

theory to use the principle that people

are C&pabte of both thinking and feeling

reactions to stimuli.

Both of these theories have compounded the discussion about how advertising works. The balance or this

paper is an attempt to regain perspective.

most involved and others where feeling

dotnin&tes: (here are situations thai [require mare involvement] and those that

[require less]. The combination of

these reference points produces a strategy matrix (hat encompasses mast of

the traditional theories as well as the

various LEASNFEEL-DO hierarchy

models just discussed.

Thinking and feeling are a cantintnim

tfi the sense (hat some decisions involve one or the other, and many involve elements of both. The horizontal

side of the matrix conveys this hypothesis and further proposes that over

time Iftere is .movement fram thinking

toward feeling. High and low [involvement] is also a continuum, and the

vertical side of the matrix displays this.

It is .suggested that over Iliac high

[involvement] can decay lo relatively

low [involvement].

Four quadrants are developed in the

matrix, with the dotted line in [Figure

3] indicating a soft partition between

them. The solid line arrows visually

depict the evolution of consumer tendencies as importance wanes and thiriking diminishes with respect to particu-

Figure 3

S-FEELING

THINKINGH

L

G

H

An FCB Model

Irk order to provide a structure that

will integrate the traditional theories

and LEARN-FEEL-DO hierarchy

models with consumer involvement

and brain specialization theories* a new

FCS approach to advertising strategy

is called foi. This requires building a

matrix to classify products and services.

Here are (he pieces for dlia now FCB

strategy model;

• " Thinking" and "Feeiing"

* 'High" and "LQ*J" [Jnvoiveraent]

This outline suggests that there are

purchase decisions Where thinking is

lar products and services. The

quadrants outline four potentially major goals for advertising strategy: lo be

informative, affective, habit Forming or

to promote self-satisfactjon.

What does thjfi matrix reveal? Each

quadrant

•*

• Helps isolate specific categories for

strategy planning.

• Approximates one of the traditional

consumer theories (Economic. Psychological, Responsive. Social),

• Suggests a variant hierarchy model

as a strategy g^idc,

• And implies considerations for crtdlive, media and research.

The following detailed: chart [Figure

4] expands upon these points. Taking

[he quadrants separately, a number of

strategy possibilities are suggested:

QiiMtowt t—High [knrofreaKatyilibutJng (InformatlYe)- This implies a large

need for information because of the

importance of the product sind thinking

issues reiated ta it. Major purchases

(car. house, rurnijhings) probably

qualify and, initially, almost any new

product which needs to Convey what it

is, its function, price and availability.

I I.

N

V

O

L

V

INFORMATIVE

2,

AFFECTIVE

4.

SELF-SATISFACTION

E

M

E

N

T

L J 3.

OH

WV

O

I,

V

£

M

E

N

T

HABIT FORMATION

{

30

VXA124 6221

VXA124 6221

http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lsw36b00/pdf

USX271 77G

Volume 20. Number 5, October 19&Q

Figure 4

Hem Advertising Works: Planning Model

-+- FEELING

THINKING

H

I

G

II

I

N

V

O

L

V

E

M

E

N

T

ON

wv

o

L

V

E

M

E

N

T

I N F O R M A T I V E (THINKER]

CA H. HOUSE-FUR NICHING 5NEW PRODUCTS

MODEL:

LEAKN-FEEL-DO

[ Economic?!

Possible ImpH«iti.<.mS

Recall

TEST;

Diagnostics

Lpng Copy Faimal

MKI>1A:

Hcflettive Vehicles

CREATIVE: Specific Jnfarniaiicin

Dcmans.tretiw

•4

HABIT F O R M A T I O N (UPER) i

\

FOOD-HOUSliHOLD ITEMS

\

MODEL:

DO-LEARN-FEEL

|Respunsjvc?l

Passible Implications

TEST:

MEDIA;

CttEATIVF:

The basic strategy model is the typical

LEARN-FEEL-DO sequence where

functional and safient information is

designed Lo build consume auHudinal

acceptance and subsequent purchase.

The Economic model may he appropriate here as well. A consumer here

might be' pictured as a "Thinker11. Creatively, specific Ltifoimsrton and demonstration are possibilities, Long copy

Format and reflective, involving media

may be necessary lo literally "gel

through" with key points of consumer

interest. If strategy research has defined the. significant message to he communicated, recall testing and diagnostic

measures will help evaluate the effectiveness of a proposed ad.

Quadrant 3—High pEiTvoh-aDeatVKeHng

(Affective). This product decision is fnvolvi ng, but specific Information is less

important than an attitude or holistic

feeling. This is so because the importance is related to ch& person's selfesteem {Psychological model). Jewel-

Sales

Small Epacc Ads

10 Second l.D.'-s

Radio; POS

Reminder

2.

A

-

A F F E C T I V E |FEELER|

J E W f, LK Y- CO SM ETICSFASHION APPAREL-MOTORCYCLES

MODEL;

FEEL LEARN DO

[Psychologic I?]

Possible Implications

Attitude Change

TEST:

Emolion Arousal

Large Space

MEDIA;

Image Specials

CREATIVE; Executions I

I nip-act

SELF-SATISFACTION |REACTQft|

CIGARETTES-LIQUOR-CANDY

MODEL:

OO-FEEL-LEARN

(Social? |

Possible Implications

TEST:

_£aies

MEDIAt

Billboards

Newspapers

1'QS

CREATIVE: Attention

ry, cosmetics, and fashion apparel

meaningfully exploited. Most food and

might fail here, A functional example:

staple packaged goods items likely bemotorcycles. The strategy requties

long here. Brand loyalty will be a funcemotional involvement on the part of fr tinn of habit, but it's quite likely mosE

the consumers, basically that they beconsumers have several "acceptable"

came a "feeler" about (he product.

brands. Over lime many ordinary prodThie niodel proposed is; FEELucts vftl mature wid dssteod icto this

LEARN-DO. Creatively, execulional

commodity limbo, The hierarchy modimpact is a possible goal, while media

el is a DO-LEARK-FEEI, pattern

considerations .suggest dramatic print

which is compatible with the traditional

exposure or "image" broadcast speResptrnsivt; theory. It suggests that

cials. Copy testing won't get much help

simply inducing trial [coupons, free

from message recall since the effect is

samples) can often generate subselikely to be non-literal; attitude shift

quent purchase more readily than

testing or emotion arousal (autonomic,

pounding home undifferentiating copy

psychogalvanomcter) tests may be

paints. This consumer can be viewed

more helpful in determining advertising

as a "doer". Creatively what is reeffect.

quired Is to stimulate a reminder for

the product. Media implications might

Quadrant 3—t.ow {hvotamentFInuik-include small space ads, 10 second

ins (Mabit Formation). Product deciI.LVs,. point-of-sale pieces and radio.

sions tn this area, involve minimal

The idea] advertising test would be a

thought and a tendency to form buying

sales measure or lab substitute; reeull

habits for convenience. Information, to

and/or altitude change tests may not

the extent that it plays a role, wiH be

correlate with sales and therefore be

any point-of-difference that can be

31

VXA124 6222

V X A J 2 4 6222

http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lsw36b00/pdf

Jimrnul uf Advertising Research

misleading. This is a tioublesuine

quadrant because so many commonly

used products and services are here

and require very detailed and careful

planning effoit.

Quadrant 4—EXM [bivoh'einmtyifeefing

(Self-Satisfaction). This low (invqivcmfirJj area seems to he reserved for

those produces Chat satisfy personal

Castcs-T-ciEarctres, liquor, candy, movies. Imagery and quick satisfaction arc

involved. This.u a DOFEEL-LEARN

model with some application of the

Social theory because 5 P imaiiy products here fit into gftjup situations (beer,

soft drinksj. This Consumer is a "reactor" whose logical [Merest will be

hard to hold and short lived, Creatively, it's basic to get attention with some

consistency. Billboards, potni-cif-sale

and newspapers might appJy here.

Copy testing will need to be salcs-orien led because recall and aitEtu.de

change may not be relevant.

These comments are meant to be

thought-starters rather than a formula

iat planning. The options clearly depend upon tfie category, brand., sales

trtndfc and marketing objectives Also,

it's not necessary to be restricted to

jUit these fullr possibilities in Usinjj this

matrix. For example, two other hierarchy models are available:

* Between quadrants 1 and 3, a

LEARN-DO-FEEL sequence might

apply as consumers go dtrecdy frominforelation to trial.

• Between quadrants 2 a n d 4 , a F E E L DOLEARN model suggest* acting

upon an initial feeling and purchasing.

Also- some products conceivably belong between quadrants 1 and 2 or 3

and 4, requiring elements of both learn

.and Feel simultaneously. The options

for placing products in the proper area

are challenging indeed. Bat by thinking

a product through the system, using

available research and (naj[3u cine fit

judgement, the advertising strategy implications can become clearer and more

manageable.

Experience in using die matrix hits

shown thai it stimulates a dynamic

approach. IF a brand is in quadrant 3,

fur example, marketers might want to

conskl« features or benefits to move

rt up for KTeatct consumer involvement, or ways to move it to the right,

considering emotional aspects of its

place in people's lives. TfiCre are many

possibilities.

What this F£B model saya is that

consumer stiltY into a product should

be determined for information (learn)',

attitude (feel) and behavior (do) Issues

to develop advertising. We help do (hi?

U&ing basic consumer research. The

priority of learn over feel, feel over

learn, Or do over either learo-feel, has

implications for advertising strategy,

creative execution, media planning and

copy testing.

To fully appreciate what this change

means, recall lhat the LEARN-FEELDO sequence has been endorsed for

years as the only "legitimate" model

of advertisfng effectiveness, Its linearity has been forced into situations

where il simply didn't appEy, Bu| it is

only one of several models. Furthermore, it's nO longer a straight-line concept, but, rather, circular [see Figure

5J.

Unfortunately, few advertising strategies are simple. Many products have

l£arn, feet and do in varying degrees,

beat reprfe&enled perhaps by overlap

[see Figure 6}.

The fundamental hypothesis of this

FCB mudcl can now be smted: An

advertising strategy is determined by

specifying {1} the consumer's paint-of

entry on the LEA.RNFEEL-DO

continlium and {2) the priority of tearrj

versus fe el versus do for making a sate.

Specifically, the strategy issue is

whether to develop product fcaiuresT

brand image or some combination of

both:

• To the extent that a brand has hard

news, with disiiticl prod&ct features,

and can lint its name to them, the

Sate centers on "learning", .with

"feeling" and' 'doing 1 ' Coming after,

• Lacking such information, where a

product gives its users an identity

via intangible/emotional features

leading Jo an image, the sale centers

on 'Teelings 11 and proceeds to

Figure 5

FEEU

J LEARN

DO

Figure 6

v,

]tarning" and "doing".

* As brands endure and achieve fixed

places in the consumer's mind, buying may become routine and consist

primarily of "doing" with very litde

conscious •'learning"'1 or "feeling".

The more the strategy matches consumer purchase experience, the better

the advertising will be "mternaEized"

or "accepted," Advertising may now

have to bu the right commtirticatron

-experience" for the consumer as well

as the right "message".

Implications Tor Advertising

Development

Not ail advertising works in the same

way, Sometimes communication of key

ijifocination and salienl emotion will be

needed to get a sale: at other tunes

consumers wi]| need one, bui not both;

and often buying m^y occur with little

or no information and emotJon. The

purpose of strategy planning is to identify the information, emocioa or action

leverage for a particular product, build

the appropriate advertising mode! and

then execute itIt's impossible to speJI out the many

32

VXA1

VXA124 6223

http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lsw36b00/pdf

Volume 20, Number

ways, this F C B model can help u s .

Several management, creative, media

and research implications are most apparent:

Management.

• Become more flexible in using t h e

L E A R N - F E E L D O model;

* Set t h e goal t o iufurm, persuade and/

or impel p u r c h a s e and get client

agreement:

• And be a w a r e t h a t commonicaricii

s t r a t e g y c a n shift a s a p r o d u c t

eva|ves.

•

•

•

•

*

•

Creative.

Every ad shouEd t r y to get the consumer lo think, feel or do something

about the product;

For low-involVcrttttlE products with

undifferentiated features, executionat style c a n be the major task;

And " s u b j e c t i v e " opinions about t h e

strategy o r campaign may be as p r o ductive as "'objective" management

comments Tor consideration.

Media,

The exposure plan should r e m e m b e r

the L E A R N - F E R I . - D O triad to get

the most out of the a d s ;

Media vehicle judgements can use

this FCB model as a guideline;

And. creatine planning beyond the

audience n u m b e r s becomes almost

a necessity.

Research.

* Copy testing must be done with target respondents for valid results;

* Measurement should be for the relevant effect (recall* attitude c h a n g e .

Sales) that m a k e s a difference;

* And tile account t.eam Ought lo agree

before, testing which execution to

u s e if the results a r c close ( b e c a u s e

t h e y often arc aad require judgements anyway}*

This FCB strategy planning model is

not an ail-purpose cure, i t ' s P guide to

help organize-the advertising objectives

for a product. The account team has to

u i e product research to determine the

brand's leverage and then build a strategy ihat inenrn urates creative, media

and cupy testing projects. If done properly, the parts should fit together.

The historical conviction that attention, communication and peistiasion

must necessarily p r e c e d e a sale h a s

been weakened; by n e w consumer theories. It depends upon the product dynamics. Attention w e certainly must

have, but what kind of cornmtiE.cation

and persuasion, and lo what p u r p o s e ?

Thoughtful u s e of the F C B s t r a t e g y

model should help us h e :

• Thorough in advertising planning

• Flexible in design and execution

• CompTrehensive in c o n s u m e r testing

• Skeptical of fads and untested theories

• And open-minded about the future.

As professionals we know that advertising works w h e n it's on target.

The task is to find ways to be on target

more often so it can w o r k .

[References]

Articles

Bernaccrti, M . D . , The Regulating Advertising Rationalist;

Journal of Advertising Reaearcri; October, 197S

5. October

Iflfitf

sumtrr Ckotce; Journal of Consumer

Research, M a r c h , 1976

Olshavsky, R. W. & G r a n b d s , D. H . .

Consumer Decision MoMng-~Fact

or

Fiction?

J o u r n a l of C o n s u m e r R e search, S e p t e m b e r , 1979

Palda, K., The Hypothesis

Of A Hierarchy Of ^Effects; Journal c-f Marketing Research, February, 1966

Robertson, T. S., Low

Commitment

Consumer Behavior. J o u r n a l of Advertisini Research^ April, 1?76

Weinsteui, S,. Brain Waves

Determine

The Degree of Positive Interest in TV

Commerciais And Prim Ads; i6th A R F

Conference; May, 1978

ftwks

Brit., 5 . 11., Consumer Behavior

And,

The Behavioral Sciences; CJ96S) J . S.

Wiley SL Sons

Prill, 3 . H . , Haw Advertising Can Use

Psychology's

Rules

Of

Learning'

P r i n t e r s Ink; S e p t e m b e r 2 3 , 1 9 5 5

Engel, I, R , Koilat, U. & Blackwetl,

R . D . , Consumer

Behavior.

<i°78)

Dryder. Press

Davis, J, L.b Who Cares? The Implications oj' Brain Research For Advertising; Annual ART Conference Proceedings; October, 1978

H o w a r d , J. & Sheth, J., The Theory

cf Buyer Behavior; (1969), J. S. Wiley

Farley, J. & Wng, L . , An

Empirical

Test of the HawardSheth

Model of

Buyer Behavior; Journal of Marketing

Research; N o v e m b e r , 1970

&Sons

Markin, R., The Fsychohgy

Of Consumer Behavior: ( l % 9 ) Prentice-Hal]

Nicosia, I'"., Consumer Decision

A T O T ; (1966) Prentice^Hall

Proc-

KorJer, P . , Behaviuraf

Models

for

Analyzing Buyers, Journal of Marketing; October, 1965

Raj", M. L., Marketing

Communication ond the Hierarchy-of-Effects:

New

Model? for Mass Communication

Research; (1373} Sage Publications

Krugman, I I . ^ r Memory Without Recall, Exposure

Vfithfiuf

Perception:

Journal of Advertising R e s e a r c h ; August, 1977

Robert SOU, T. S.Y Consumer Be-iuivior;

(1970} Scott. Forcsman & C o .

Lavidge, R. & Stcincr, G . , A Model

For Predictive Measurements

of Advertising

Effectiveness;

J o t t r n a t of

Marketing; O c t o b e r , 19GI

McGuire. W, J.., Some Internal

etiological Factors Influencing

Psy*

Con-

Robertson, T, S., Innovative

Behavior

And Communication;

(I97J) Hott,

Rinehart

Rothschild, M. I,., Adverdsiitg

Strategies for High and -Vpw

Involvement

Situations; Attitude Research Plays for

High Stakes; (19793 AMA

33

VXA1Z4 6224

6224

http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lsw36b00/pdf