Uploaded by

Antonio.Campello.15

LED Streetlights Commentary: Microeconomics & Efficiency

advertisement

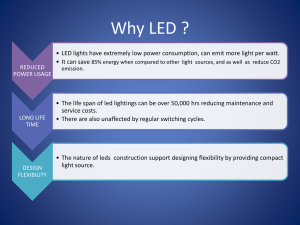

Commentary 1 Title of the article: LED Streetlights Bring Cost Savings, and Headaches, To Colorado Cities Source of the article: Colorado Public Radio online site http://www.cpr.org/news/story/led­streetlights­bring­cost­savings­and­heada ches­to­colorado­citi es (Accessed 20 February 2017) Date the article was published: 15 September 2016 Date the commentary was written: 17 March 2017 Word count of the commentary: 792 words Unit of the syllabus to which the article relates: Microeconomics Key concept being used: Efficiency Article LED Streetlights Bring Cost Savings, And Headaches, To Colorado Cities The city of Denver is in the midst of a nearly $2 million project to replace lighting poles, fixtures and bulbs on the 13-block 16th Street Mall. On their way out: High-pressure sodium lights that have an orange hue. On their way in: White LEDs. “These street lights are about 30 years old. It was time for an upgrade,” said Denver Public Works spokeswoman Heather Burke. “Technology changes. It was time to change with it,” Denver planned for years before converting the iconic 1970s-era light fixtures along the 16th Street Mall sidewalks to LED lights. They meet new guidelines issued this June by the American Medical Association (AMA). Across the country, more than 10 percent of outdoor lighting is powered by LEDs. Because the energy savings can be as much as 50 percent, many cities want to make the change. But there are also health implications to consider; LED lights that appear too blue can suppress melatonin production, which can lead to increased diabetes and depression. The newer LED lights cost the same, provide the same cost savings and last as long as older versions, so “there’s absolutely no reason to put in bad lighting,” said Dr. Mario Motta, who serves on the AMA’s Council on Science and Public Health. “You can put in good lighting.” Smarter Technology In June, the AMA issued three core guidelines for cities. It suggested using lights that are 3000 degrees Kelvin or below, referring to the color temperature of lights, where lower numbers appear warmer. Most older versions of LED streetlights installed before 2016 were 4000 Kelvin or above. The AMA also advised cities to properly shield LEDs to reduce glare, and to make lights dimmable. Professional groups including the Illuminating Engineering Society criticized the guidelines as too specific. The U.S. Department of Energy pointed out that blue light is not unique to LEDs. Lighting designer Nancy Clanton of the Boulder-based firm Clanton & Associates said the technology that comes with LEDs can offer cities new options. Clanton has helped design LED streetlights for a number of cities including San Diego and Anchorage. In San Jose, she worked to install smarter technology that allows the city to dim street lights. "Right before the bars close, they increase the lighting level so that everyone knows it’s time to go home, and then they decrease it back down again,” she said. This dimming technology will be installed in Colorado Department of Transportation lights in the coming years. Dimming is also possible on new lights Clanton’s firm helped design for the 16th Street Mall. Denver Public Works spokeswoman Heather Burke said the poles and globe lights will look the same to most. But there’s one noticeable change. Designers have restored a halo of lights that has been dark for years; lost when Denver planners switched light bulb types decades ago. "The twinkle rings, you can see that ring up there. On the old lights they were inoperable for a long time. So those are restored now. And it’s going to create a brighter more inviting light for folks,” she said. The AMA guidelines were a challenge for cities that had already invested time and money converting to LEDs. Some cities like Lake Worth, Florida, changed course and opted for warmer LED streetlights. For Ouray, on the Western Slope, which installed LEDs in 2009, the AMA guidelines released this year were just another bump in a long road adjusting to the new technology. City Administrator Patrick Rondinelli said Ouray was the first in the state to make the move. A huge selling point was preserving darker night skies. “In Ouray we’re very fortunate. We can actually still see the Milky Way. You get to Denver, you can’t see that anymore,” he said. But since 2009, Ouray has noticed a few hiccups as an early adopter of LED technology. LEDs cast a more narrow light pattern compared to other lights. After installation, suddenly large sections of neighborhood blocks went dark. Only the intersections -- where the LED street lights were placed -- appeared lit. That’s a problem when you have bears walking down side streets. “As our law enforcement are trying to chase bears around and get them out of the community, they have a hard time seeing a lot of that,” said Rondinelli. Rondinelli said he doesn’t know what to make of the recent AMA guidelines. Overall, citizen feedback has been positive and cost savings have helped the city’s bottom line. “We’ve had some lessons learned along the way. But there’s no regrets,” he said. Since LED technology changes so quickly, there may actually be a benefit in moving slowly. If a proposed budget item is passed, Fort Collins will swap about one-third of its streetlights to LEDs in 2017 and 2018. Fort Collins Engineering Manager Kraig Bader said the city hopes to install 3000 and 4000 Kelvin lights with varying brightness depending on how large and busy streets are. It plans to study the results before converting the rest of the city’s lights. “In essence we’re going slow to go fast later on,” he said. (Colorado Public Radio, Sep 15, 2016) http://www.cpr.org/news/story/led­streetlights­bring­cost­savings­and­headaches­to­colorado­citi es Commentary Many problems are associated with the economic evaluation and provision of public goods. How should communities proceed with the installation of LED streetlights in order to ensure that there is allocative efficiency, with the social surplus being maximized where marginal social cost=marginal social benefit (MSC=MSB)? Streetlights are public goods because they are non-rivalrous and non-excludable. This causes complications when attempting to analyze their advantages (Figure 1). Figure 1: Cost/benefit model for sodium and LED streetlights The MSC1 curve represents the supply curve of sodium streetlights. The marginal private benefit (MPB), or demand curve for streetlights, does not intersect with the MSC curve because streetlights are public goods. This signifies that the free rider problem is occurring; no-one (or, in reality, very few people) will buy the good because they are all waiting for someone else to buy it. However, the city government ought to pay for these goods, as the MSB of streetlights is high. Before the implementation of LEDs, the optimum or efficient output was Q1 where the MSB curve intersects the MSC1 curve. Although the article mentions that LEDs “cost the same”, the MSC2 curve for LED streetlights is below the MSC1 curve. This is because private costs are lower, and “energy savings can be as much as 50 percent”, signifying that the costs of using the lights, for many years after implementation, will decrease significantly. Therefore, the MSC curve will drop. Simultaneously, the efficient quantity of LED streetlights the city ought to acquire will increase from Q1 to Q2. From the diagram, it can be seen that the city can reduce the costs spent on streetlights and at the same time obtain more. The extra lights can be stored until some need to be replaced, implying that costs in the budget for future purchases of the replacement of lights can also be saved. However, the disadvantages of LED are associated health problems, namely an external cost of consumption (Figure 2). Figure 2: Negative Consumption Externality of LED streetlights Because streetlights are public goods, the D (MPB) curve has been shown to be almost irrelevant to the model. Instead, the externality (“health implications” of “increased diabetes and depression”) is shown by the downwards shift of the MSB1 curve to MSB2. The marginal external cost notated in the diagram supposedly measures the per unit negative impact of individual health problems on society. The diagram shows that the efficient quantity of LEDs is not QP (initially predicted quantity), but QA (actual quantity). It also implies that in order to dissuade cities from implementing harmful LED lights, the efficient “price” of the LED lights at QA will not be cost/benefit2, where MSB2=MSC, but instead at cost/benefit3. This diagram supports Fort Collins’ argument for changing only part of the city’s streetlights to LED lighting. It illustrates that because of the negative externality, LED lighting, while apparently more “cost-efficient”, has problems. However, the negative externality is probably not so large that LED lighting should be completely eliminated from the city government’s options. It makes sense for Fort Collins to “swap one third of its streetlights to LEDs”. Furthermore, Fort Collins mentioned that they hope to “install 3000 and 4000 Kelvin lights with varying brightness” and “study the results” before making further decisions about whether they will replace the rest of the city’s lights. This exemplifies how communities may use economic models to assess the advantages and disadvantages of public goods, with the aim of improving the well-being of their citizens and reaching allocative efficiency. However, there are also many limitations to the models above. The models are all static, and do not reflect development of LEDs; an example of rapidly improving, new and clean technology. Research has probably been conducted in order to reduce harmful blue light, and costs of the lights have also been reduced. As the article suggests, the cities have probably taken measures to reduce negative impacts, such as warmer lights, shielding and dimming. Additionally, more variables should be considered. For instance, the article mentions positive externalities of consumption of LEDs due to the ability to preserve darker night skies. There are also problems associated with LED light patterns being narrow and therefore posing danger of bear attacks. The city must consider different aspects because LEDs are public goods which need to benefit citizens, not only the city budget. Finally, all the curves and points on the models are qualitative; although they reflect directional shifts, it is impossible to determine the monetary cost of negative and positive externalities. Therefore, applying corrections based on these static models will be unrealistic. In conclusion, analysis shows that installation of LEDs in some streetlights will save costs while minimizing negative externalities. However, in order to ensure that allocative efficiency is improved, the city government should closely monitor effects on society and citizens’ feedback to make decisions based on reality rather than just on the abstract models. Commentary 2 Title of the article: The country with the world’s most progressive taxes has the world’s highest income inequality Source of the article: Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/07/16/what-american-lib erals-could-learnfrom-south-africa/?utm_term=.5738f496ae30 (Accessed 10 October 2017) Date the article was published: 16 July 2017 Date the commentary was written: 10 November 2017 Word count of the commentary: 781words Unit of the syllabus to which the article relates: Macroeconomics Key concept being used: Equity Article The Washington Post The country with the world’s most progressive taxes has the world’s highest income inequality By Max Ehrenfreund July 16 South Africa has the world's most progressive tax system, according to a new report. South Africa is also, by another measure, the world's most unequal country -- making it a cautionary example for U.S. liberals about the limited power of taxation to remedy inequality. Yes, taxing the rich more and the poor less can have benefits, but many experts argue inequality is more meaningfully addressed by spending on public programs that provide for people's basic needs while giving them an opportunity to get ahead. In particular, that requires ensuring people have access to education, training, transportation and health care. And funding those enterprises requires more than just soaking the rich. In northern European countries -- where economists have found that people who are born poor are more likely to make it into the middle class -- governments also rely on broad taxes that force the middle class to pay more as well. "The basic story is taxes do not change the income distribution," said Graham Glenday, a tax scholar at Duke University who was born in Cape Town, South Africa and plans to retire there. "Changing the income distribution is much more of a dynamic thing that comes about if poor people can actually move up," he said. "That obviously takes, sometimes, generations." The new report, published Sunday by Oxfam, ranks 152 countries on how well their economic policies are designed to address inequality. South Africa ranks first on taxation. The rich pay steeper rates, the corporate tax is hard to shirk and a national value-added tax includes exemptions for food and other staples that are major expenses for the poor. "It’s quite an efficient system that tries, to the extent that’s possible, to really, kind of, balance the equation," said Sipho Mthathi, the director of Oxfam South Africa. "It is one of the most efficient tax systems in the world." But despite ranking first in tax redistribution, South Africa ranks slides to 21st in the overall measure of addressing inequality, just ahead of the United States at 23rd. A poor score on the labor market -- South Africa does not have a minimum wage, for example -- brings down the country's general ranking. The other countries in the top 25 are all developed nations, almost all of them in Europe. Sweden ranks first, followed by Belgium, Denmark and Norway. There are many methods of measuring inequality, but among the most common is the Gini coefficient -- a measure of the share of income that would have to be redistributed to achieve perfect equality. Based on the Gini coefficient, South Africa is the most unequal country in the world among those for which data are available, according to the World Bank. As of 2011, the most recent year for which data are available from the bank, the coefficient was 0.63 in South Africa. Data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) show that inequality has increased in South Africa since 2000, when the Gini coefficient was 0.58. The coefficient for the United States was just 0.41 as of 2013, but that figure is still relatively high for a rich country. It is difficult to compare economic policies across countries. Different approaches may work better for some countries than others, and the data is not always available in the same form. Any ranking necessarily involves a degree of subjective judgment. For instance, Oxfam did not rank countries' systems of taxation according to a strict measure of fiscal progressivity, that is, the distribution of the burden on people of different levels of income. (The northern European and Scandinavian tax systems also perform well in the report, despite the relatively high taxes paid by the middle class in those countries.) Instead, the authors of the report considered several factors. South Africa performed well on all of them. The South African government consistently collects between 27 percent and 29 percent of the country's gross domestic product in revenue, Glenday said. He added that those numbers are comparable to those for the United States -- where general government revenue totaled 33.5 percent of GDP in 2015, according to the OECD. That is despite the fact that the United States is a much richer country, where taxpayers can afford to pay much more. In the United States, GDP per person is more than 10 times that of South Africa. Indeed, Americans pay only 68 percent to 71 percent of the maximum amount of taxes that the government could theoretically collect, according to researchers at the International Monetary Fund. The estimates for South Africa are higher -- between 75 percent and 76 percent, depending on how the maximum is calculated. South Africa is able to collect so much in taxes in part because of a bureaucracy that is unusually effective for a developing country. While corruption is a serious problem in South Africa, the tax authorities have a reputation for professionalism. "They collect it very competently," Glenday said. Hefty penalties for cheating the system discourage abuse, according to Mthathi. "It’s created a culture where it’s not easy for people to just not follow the rules," she said. Another factor that might make South Africa's tax system particularly progressive is that about one fifth of tax revenue comes from taxes on corporate income. That is roughly twice the share of U.S. taxes that is paid by corporations. People who own corporations, whether privately or in the form of publicly traded stock, tend to be wealthier, and most economists believe that steeper corporate taxes tend to favor the poor and the middle class. An important exception is Kevin Hassett, President Trump's nominee to serve as chairman of the White House's Council of Economic Advisers. Hassett has argued that workers wind up paying a substantial share of corporate taxes in the form of reduced wages. By Oxfam's reckoning, though, the United States would fall in the rankings from 23rd to 29th if Trump's agenda were implemented. Despite decades of progressive, efficient tax policy in South Africa, the country's extreme inequality is stubbornly persistent. "It doesn’t mean that the country doesn’t have problems," Mthathi said. In particular, she said, South Africa could spend the money that it collects more efficiently to reduce poverty and create opportunity. The problem of corruption makes it more difficult for the government to achieve those aims. And as Glenday pointed out, South Africa's public education system is notoriously poor -- a grave obstacle to economic development over the long term. That is arguably a legacy of the era of apartheid, when schools for white students were much better than those for students of other ethnicities. Without good tax policy, South Africans might be much worse off, but that country's example suggests that progressive taxes on their own are not a solution to inequality. "It’s not just about collecting money, and making sure that is done is fairly and progressively," Mthathi said. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/07/16/what-american-liberals-could-learnfrom -south-africa/?utm_term=.5738f496ae30 Commentary This article illustrates the problems associated with income inequality and inequity. Contrary to popular belief, despite having the world’s most progressive tax system in the world, South Africa has high income inequality. What might be the implications of the Gini coefficient of South Africa and how does progressive tax influence the income distribution? Progressive taxes are usually designed to reduce the inequality between people by taxing the higher income workers proportionately more than the lower income workers. As the article mentions, it is often considered to be a “remedy to inequality”, implying that there is more equity. However, South Africa still has a high degree of income inequality. It is mentioned that the Gini coefficient in 2011 was 0.63. This is illustrated in the below income 𝑎𝑎𝑎𝑎𝑎𝑎𝑎𝑎 (𝐴𝐴) distribution diagram where the 𝐺𝐺𝐺𝐺𝐺𝐺𝐺𝐺 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐 = 𝑎𝑎𝑎𝑎𝑎𝑎𝑎𝑎 (𝐴𝐴+𝐵𝐵) Naturally, the question will follow: Why, despite the progressive tax, does South Africa have a wide gap in the income distribution? Inequality may depend on the productivity of resources owned, non-competitive labor markets, stage of economic development of the country, the type of economy, society and culture, luck, or a combination of these. However, the flaw in this article is that it does not make it clear whether the Gini coefficient provided is for pre-tax income or disposable income. If the Gini coefficient is for pre-tax income, the problem is the significant difference in the wages the workers are receiving. This means that the reasoning provided by the article is insufficient because with the pre-tax figures, no measure of the relationship between income inequality and progressive taxes has been provided. Perhaps, the Gini coefficient for the disposable income will actually show that the world’s most progressive tax does indeed greatly reduce inequality. On the other hand, if the Gini coefficient is for disposable income, it is implied that the progressive taxes may not have as much influence on the redistribution of income as expected, which supports the article’s viewpoint. The diagram below shows that effect on income distribution due to government spending may be greater than the progressive taxes. In the above model, the Lorenz curve C reflects the income distribution of South Africa before taxes are imposed, due to other factors such as inefficient government spending. Then the effect of the progressive taxes is shown by the less curved Lorenz curve D. It is shown that the taxes will only slightly make the area enclosed by the curve smaller. Therefore, the model above illustrates the possibility that progressive taxes are indeed not very effective in remedying inequality, as the article suggests. However, the article also states that inequality in South Africa may be due to corruption and a lack of spending on infrastructure, educational and health facilities. While it may be true that the tax system itself has severe penalties for cheating it, corruption could occur afterwards. This suggests that the tax is not being used effectively to counter eventual structural unemployment due to lack of education; the problem lies with the effective utilization of the tax revenue and not the progressivity of the tax. This is significant because it implies that progressive taxes, while less effective on their own, could lead to effective supply-side policies using the tax revenues, if corruption decreases. Measures such as increased education and training would encourage occupational mobility and lower unit costs, shown by the movement of the short run aggregate supply curve to the right from SRAS1 to SRAS2. This will also reduce frictional and structural unemployment due to a more flexible labor force and increased quality and quantity of the production of goods. Furthermore, investment in human capital is an increase in the quality of the factors of production with higher productivity, which can be represented by a shift the long run aggregate supply curve (LRAS1 to LRAS2) of South Africa. If used correctly, progressive tax revenues may lead to sustained economic growth and reduced income inequality in the future. Limitations of the economic theory used include the fact that effects of other factors used to promote income equality, such as transfer payments, government subsidies and intervention in the labor markets have not been compared thoroughly in order to assess the effectiveness of the progressive tax in improving equity. Economists will also have to observe the effects in the long run to make viable conclusions, as South Africa is a developing country and has the potential for higher economic growth. In conclusion, the ambiguity in the article about the source of South Africa’s large Gini coefficient makes the extent of the influence of progressive taxes in reducing inequality questionable, although the tax system does appear to be less significant than that of government expenditure in promoting equity. Commentary 3 Title of the article: E.U. and Japan Reach Deal to Keep ‘Flag of Free Trade Waving High’ Source of the article: The New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/08/business/economy/eu-japan-trade.html (Accessed 22 January 2018) Date the article was published: 8 December 2017 Date the commentary was written: 5 March 2018 Word count of the commentary: 800 Unit of the syllabus to which the article relates: The Global Economy Key concept being used: Interdependence Article E.U. and Japan Reach Deal to Keep ‘Flag of Free Trade Waving High’ By Prashant S. Rao and Jack Ewing Dec. 8, 2017 The European Union and Japan said on Friday that they had finalized a sweeping deal that would create a free trade area covering more than a quarter of the world’s economy, pushing against rising calls for protectionism in much of the West. Leaders of both parties to the agreement trumpeted its strategic, as well as economic, importance. That it was announced just hours after Britain and the European Union broke a deadlock to start a new round of talks over that country’s withdrawal from the bloc only heightened its symbolic impact. The so-called economic partnership agreement, which would be one of the largest free trade deals ever, “demonstrates the powerful political will of Japan and the E.U. to continue to keep the flag of free trade waving high,” the Japanese prime minister, Shinzo Abe, and the president of the European Union’s executive arm, Jean-Claude Juncker, said in a joint statement. The deal is subject to ratification by lawmakers in Europe as well as Japan, but Mr. Abe and Mr. Juncker said that they were confident that once in place, it would “deliver sustainable and inclusive economic growth, and spur job creation.” “It sends a clear signal to the world that the E.U. and Japan are committed to keeping the world economy working on the basis of free, open and fair markets with clear and transparent rules fully respecting and enhancing our values, fighting the temptation of protectionism,” the leaders added. The agreement also reaffirms its parties’ commitment to the Paris climate accord, from which the Trump administration has said it will withdraw. Tokyo and Brussels began trade talks in 2013, and said in June that they were nearing a deal. Japan trades less with the European Union than it does with the United States or China. But completing a deal with the European Union became a more urgent priority for Tokyo after President Trump’s decision in January to withdraw the United States from another agreement, the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Japan has also pushed to revive that deal, even without the United States. Japan had effectively paused its talks with the European Union while it focused on the larger Pacific Rim deal, which included 10 other nations along with the United States and Japan. Mr. Abe has made liberalizing trade a centerpiece of his economic agenda — a notable shift in a country that, despite its success exporting cars, electronics and other merchandise, had long shied away from trade deals. The change of direction on trade owes partly to the waning power of Japan’s farm lobby, which has fought to keep tariffs on imported agricultural products high, impeding the country’s ability to strike agreements. Japanese negotiators still focus much of their efforts on protecting farmers, but with Japan’s rural population rapidly aging and shrinking, governments no longer see making concessions on agriculture as politically fatal. The European Union and Japan have a combined annual economic output of around $20 trillion, and together would constitute a trading area roughly the size of the one created by the North American Free Trade Agreement. The future of Nafta, which comprises the United States, Canada and Mexico, has also been cast into doubt by tense renegotiations. Still, while Japan and the European Union have expressed confidence over the agreement they announced on Friday, political interests are still at play. National and some regional legislatures in Europe will have a say, a process that nearly derailed a trade deal with Canada. The main beneficiaries from the agreement are likely to be Japanese carmakers and European food and beverage producers. The deal will make it easier for European producers of cheese, beef, wine and processed meat to sell in Japan, which imposes duties of as much as 40 percent on some products. European makers of pharmaceuticals, medical equipment and trains are also expected to come out ahead. The pact also presents Japanese carmakers with an opportunity to increase sales in Europe, which has long been difficult for them. Toyota and other Japanese manufacturers have only a 13 percent share of the auto market in the European Union, in part because of import tariffs, compared to the United States where they account for about 40 percent. But Japan’s carmakers already have major manufacturing operations in Europe which are not subject to import duties, suggesting that their meagre sales also stem from lack of products that appeal to European tastes. While the pact will be important for some industries, said Angel Talavera, senior eurozone economist at Oxford Economics in Britain, its overall economic impact will be modest. The deal “does not materially alter the outlook for the eurozone, as Japan represents only around 2 percent of total exports,” Mr. Talavera said in an email. “I don’t think this is a game changer.” Commentary Interdependence between different sectors within one economy and between global economies can cause clashes when trade is liberalized, especially if declining industries are involved. The Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA), a free trade agreement (FTA) between the European Union (EU) and Japan, symbolizes the advantages of free trade, while also raising issues about the protection of declining industries and about flows of trade between all economies. An FTA reduces or eliminates trade barriers on goods from member countries, while allowing them to erect their own trade barriers against other countries. There will be tariff reductions on, for example, Japanese car imports into the EU and on European “cheese, beef, and wine”, among others imports, into Japan. Before the FTA, Japan had been imposing a tariff of up to 40%. Before the EPA, the price of cheese was Pw+Tariff (40%) where the quantity of imports from the EU was Q2Q3. However, when the tariff is eliminated, with price falling to Pw, the quantity of domestically produced cheese will fall from Q2 to Q1 because some Japanese dairy farmers will lower output or even give up farming in response to lower prices and their revenue will decrease from Pw+Tariff x Q2 to Pw x Q1. Thus, the quantity of imports will increase to Q1Q4. Because more efficient EU firms are producing the cheese, there will no longer be welfare losses, represented by areas a and b. Simultaneously, there will be a decrease in tariff revenue, which the Japanese government had been collecting, shown in the area GOV. A similar analysis can be made for the elimination of tariffs on Japanese car companies. Currently, “Toyota and other Japanese manufacturers have only a 13% share of the auto market”, suggesting that import tariffs placed on cars by the EU have been harming Japanese exports. However, this could be due to a mismatch between the Japanese products and the European tastes, a non-price determinant of demand. Moreover, the tariff reduction will have no impact on the Japanese cars which are manufactured in Europe. On the other hand, the EPA may negatively affect the farmers of Japan, a declining industry which has been protected for many years. Due to “waning power of Japan’s farm lobby” attributed to the aging population in rural areas, “governments no longer see making concessions on agriculture as politically fatal”. Although political effects of the loss of tariffs on agricultural products may no longer be large, there may be economic losses. The lowering/elimination of tariffs on European farm products in competition with Japanese products suggests a decrease in production of agricultural goods from QA1 to QA2, as inefficient domestic farmers are replaced by Europeans. However, it is likely that this will only result in a much smaller quantity increase of QM1 to QM2 in the production of manufactured goods. Farmers are likely to have had the job for their whole lives. Thus, relatively low mobility of the “aging population”, especially in “rural areas” can be expected. Therefore, the EPA could cause a fall in Japan’s real GDP and as total output decreases, high frictional and, more problematically, structural unemployment. The growth in car exports may lead to a decline in the economic vitality of rural areas, even though car manufacturing and farming may not seem at first to be interdependent. Similarly, infant industries (for example, wine production in Japan) may also struggle as they do not yet have the economies of scale to compete against large established overseas companies. The FTA between the EU and Japan will have various other consequences. On the one hand, trade liberalization will increase competition and incentives for firms. The consumers will be able to choose from a wider variety of goods at lower prices, as import prices will fall. There will be a rise in global allocative efficiency as specialization according to comparative advantage takes place leading to trade creation. At the same time, governments inside and outside the EPA will have to closely monitor to ensure that imports from outside the FTA are not routed through the low-tariff economy into a high- tariff economy. The phenomenon of trade diversion shows how all economies in the world are interdependent, not just those within each FTA. As indicated above, Korean cars could be imported into Europe via Japan at a lower total tariff of 3% instead of 10%, impacting both tariff revenues for each area (where government revenues from tariffs will already be lower due to the abolition of tariffs in the EPA) and competition between firms. However, some economists maintain that the EPA may provide little stimulation to the EU economy because “Japan represents only around 2 percent of exports”. Maybe rather than interdependence between the two areas, Japan is more dependent on the EU. But this could change as trade develops in the long run. ECONOMICS – PORTFOLIO: A Marks and Comments Commentary: 1 Criterion Mark Out of Justification A Diagrams 3 3 Both diagrams are relevantly labeled and usefully entitled. Switches the horizontal axis effectively from “Quantity of streetlights” to “Quantity of LED lights” for the second diagram. The explanations are clear and correct. B Terminology 2 2 Appropriate economic terminology is used precisely. Concise definition of the crucial term “public good”, while correct understanding of the other terms (such as external cost of consumption) is shown by the way in which they are used. C Application and 3 3 The use of cost-benefit analysis is well-linked to the article, being effectively applied to a non-text-book situation. The small demand curve analysis on the left of the optimum implies that a few people might be willing to pay for street lights (rather than zero consumers as implied by pure public good theory), but that does actually seem likely in a real-world situation. D Key concept 3 3 The commentary recognizes that the key concept of efficiency is difficult to measure and even more difficult to ensure, given the external costs (of LED streetlights, which meanwhile have lower monetary costs) and the benefits of streetlights. Nonetheless it is seen as necessary to try to move towards it. E Evaluation 3 3 The evaluation is balanced and comprehensive. It covers both the points made in the article and the weaknesses of the models used in the analysis. It is well summed up in the final paragraph. Total: 14 14 Marks and Comments PORTFOLIO: A Commentary: 2 Criterion Mark Out of Justification A Diagrams 3 3 Uses two different models in three diagrams. Titles and labels are correct and relevant. Recognises that the Lorenz curve diagram cannot be used for any predictive purposes, but only as an illustration. Explanations are very clear and focused. B Terminology 2 2 Plentiful use of relevant terminology with concise and precise definitions of a progressive tax and of the Gini coefficient. Uses the terminology of supply-side policies, such as unemployment, capital, etc correctly, demonstrating that their meaning is understood. C Application and 3 3 The use of the Lorenz curve model is highly relevant to the article. Uses the AD/AS model effectively and interestingly to analyse and analysis emphasise the importance of investment in infrastructure and human capital. D Key concept 2 3 The key concept of equity is mentioned initially and in the conclusion. It is appropriate to both the article and the commentary. However since both are explicitly about equality rather than equity, the link between the two concepts needed to be more fully explained. E Evaluation 3 3 Critical and focused evaluation with an especially pertinent point made in the third paragraph regarding the ambiguity of the information in the article itself. Argues effectively for the need for additional policies, rather than simply relying on progressive taxation. Total: 13 14 Marks and Comments PORTFOLIO: A Commentary: 3 Criterion Mark Out of Justification A Diagrams 3 3 Uses diagrams very effectively with explanatory titles and detailed, relevant labels. Although the first diagram is the standard tariff diagram, the other two are rather innovative in this context. Explanations are clear, correct, and focused. B Terminology 2 2 The terminology of international economics is used correctly and precisely, distinguishing, for example, between trade creation and trade diversion. Concise definitions of crucial terms, such as FTA, are provided where necessary. C Application and 3 3 the implications of statements made in the article. analysis D Key concept The analysis, using economic models or theories, effectively explains 3 3 The key concept of interdependence is used both to discuss how different sectors (farming and car manufacturing) have an impact on each other and on how economies are interdependent globally. E Evaluation 3 3 Evaluation is apparent at several points in the article, not just in the concluding paragraphs. It takes a balanced approach, considering the theoretical benefits of freer trade against the impact on Japanese farmers and rural areas. It also discusses whether the benefits (especially for Japanese car sales) might not be as large as suggested by the theories. Total: 14 14 _________________________________________________________________________________________ __ Criterion F Mark 3 Out of Justification 3 The three commentaries are each based on different syllabus units. Each article is taken from a different and appropriate source and is published less than one year before the commentary was written. Marks from three commentaries (Out of 42) 41 Total marks – including criterion F (Out of 45) 44