Printout

Sunday, January 10, 2021

5:35 PM

Difference between phonemic contrast and

phonetic contrast

Consonants are described in terms of the

ir place, manner, and voicing characteris

tics. Place refers to place of articulation,

such as location of articulation. Manner i

s the manner in which a sound is articula

ted. And voicing refers to the presence o

r absence of voicing. And these are impo

rtant concepts, because they underlie the

way we think about how consonants are

produced, and that's important in order f

or us to move on to the next step-- which

is understanding distorted speech.

So in terms of place of articulation, this r

efers to the constriction location. The pla

ce can be made at the lips, which is refer

red to as bilabial. Place can also be refer

red to as labiodental. And that's when co

ntact is between the lips and the teeth-- l

inguadental, tongue and teeth-- linguaalv

eolar, tongue and alveolar ridge. And so

what you can see that I'm doing is I'm m

oving from the most anterior position, w

hich is the lips, back in posteriorly in the

oral cavity. And so at the point where w

e get to the linguaalveolar point of articu

lation, we're talking about that tongue/al

veolar ridge contact, such as for sounds l

ike T and D, S and Z.

Moving one step further back is linguap

alatal, which is tongue and hard palate.

And then one more step back, linguavela

r, tongue and soft palate-- such as "kuh,"

"guh," "ng." And then finally, moving a

ll the way down to the level of the glottis

, where a sound such as "huh" could be

produced, or even a glottal stop as in "uh

."

Now, manner of production is how a spe

aker might alter airflow through the oral

cavity. And so we can use different kind

s of constrictions to do that. The most ba

sic is a stop, or plosive phoneme. And to

produce a stop, a speaker needs to comp

letely block air flow in the vocal tract. A

nd that can be with a complete closure, s

uch as by bringing the lips completely to

gether, building up air behind the lips-which is called intraoral air pressure, we'

re increasing intraoral air pressure-- and

then releasing that. So P and

B are examples of stop plosives.

Fricatives are a little bit more complicat

ed because the speaker has to form a nar

row constriction that air is going to pass

through. And that narrow constriction ca

n occur at different points, at different pl

aces of articulation. So for example, if n

ow

a constriction occurs at the contact betw

een the tongue and the alveolar ridge, th

at would be a linguaalveolar phoneme, t

hat's a fricative-- such as an S.

Now, affricates are a combination of sto

p and fricative. And so we can have that

complete stop flow of air immediately fo

llowed by that constriction, which is the

fricative part. So the sounds, "ch" and "j

uh" are the only affricates in English tha

t involve that stoppage followed by that

narrow constriction.

Nasals are something quite different. An

Week 1 Page 1

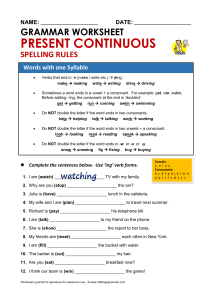

1. PHONETIC= MOTOR based problem.

Ex. LISP

a. Kid CONSISTENTLY produces the 's'

sound inconsistently if they have lisp

2. PHONEMIC CONTRAST IS PRESERVED.

a. Kid is not going to say 't' for 's'. They

are going to either produce 's' with the

front of the mouth like "thoh" OR the

SIDES of the mouth like "THUH"

3. PHONEMIC= phonological rules.

The kid may actually have difficulty using

phonemes to discriminate meaning.

And typically it's rule based so that kid may

be able to produce the T in the initial position

but can't produce it in the final position.

to differentiate or to determine if this

phonemic contrast is preserved. We use

something called minimal pairs. And the first

thing we do is we want to do a minimal pair

discrimination task.

• I want to hear if the kid can perceive the

difference. Can they hear the difference. And

so I may show them-- if they have a hard

time with producing the voiceless p and the

voice to be right 'p' and 'b' exactly the same

sound just the ones voiceless. The other ones

voice.

• I may show them a picture of a pair and a

bear.

• And then cover my mouth and say, point to

the pair point to the bear. I just want to hear

that the kid can hear the difference

• Because if they can't hear the difference, then

they're not gonna be able to produce the

difference

fricative part. So the sounds, "ch" and "j

uh" are the only affricates in English tha

t involve that stoppage followed by that

narrow constriction.

Nasals are something quite different. An

d in nasal production, there's coupling b

etween the oral and nasal cavities, which

simply means that the velopharyngeal p

ort is open, allowing the sound wave to r

esonate not only through the oral cavity,

but also through the nasal cavity. And in

English, we have three nasals-- "mm," "

nn," M-N, and "ng."

Glides are a little bit more complicated,

because there is a gradually changing art

iculatory shape. Laterals are different fro

m these other sounds because there's a cl

osure at midline at the linguaalveolar poi

nt, such as for "ul," but there's not closur

e at the sides of the tongue. And then rh

otics are involved when a tongue being b

unged typically at the center of the oral c

avity. Although in English, there can be

several slightly different tongue position

s to produce rhotics, and I'm referring to

consonantal R.

And then lastly in this pair of place, man

ner,

and voicing, we come to voicing. And v

oicing is really binary. Sounds are either

voiced or voiceless. And when phonem

es are voiceless, they're produced with t

he vocal folds open. And there's no voca

l

fold vibration. In contrast, voiced phone

mes involve vocal fold vibration. The vo

cal folds are very closely approximated t

o one another, and that's so air flow will

move through them. They'll then begin t

o vibrate and produce voicing.

Now, the way that I think is easiest to be

gin or to continue your thinking of place

ment or voicing-- and I say continue, be

cause I know that you've heard these con

cepts before-- is to pair consonant cogna

tes together. It's just simply easier to rem

ember these ideas. And so cognates are c

onsonants that differ with respect to voic

ing. But their place and manner features

are identical.

And so P and

B are cognates, because they're both bila

bial plosives. But B is voiced, P is voicel

ess. Similarly, S and Z are cognates beca

use they're both linguaaveolar fricatives.

But S is voiceless, Z

is voiced. And then of course, our only t

wo affricates in English, "ch" and "juh"

are "ch" is voiceless, "juh" is voiced. So

as your continuing to refine your underst

anding of place, manner,

and voicing, come back to this notion, b

ecause you should be thinking and group

ing these sounds in pairs whenever possi

ble. Because not every phoneme has a c

ognate, as you'll see in the next chart.

So I really like this chart, because it will

help you visualize how to group these so

unds together in terms of their place, ma

nner, and voicing characteristics. So let's

look at this together. So for example, P

and B are bilabial stops. They're both gr

ouped here. The phonemes in the slightl

y gray position are the voiced phonemes.

And the ones right next to them are thei

r cognate pairs.

So you can see here, for instance, how P

and

B are cognates, but M does not have a c

ognate pair. But this is a great reference

for you to come back to in order to make

Week 1 Page 2

So you can see here, for instance, how P

and

B are cognates, but M does not have a c

ognate pair. But this is a great reference

for you to come back to in order to make

sure that you're understanding clearly th

e place, manner, and voicing characterist

ics of each phoneme or phoneme pair.

Week 1 Page 3

So there are several ways in which we can d

iscuss consonant position. And because clini

cians will sometimes use a variety of differe

nt terms to describe consonant position, I'm

going to go through all three with you.

So first is thinking about consonant position

within a word. And this is probably the mos

t common way of describing it, often seen a

nd used by clinicians. And that means that

we will distinguish between the initial positi

on of a consonant in a word. Meaning the fir

st consonant in the word. The medial positio

n of a consonant, a consonant that's in the m

iddle of a word somewhere. And the final p

osition of a consonant, which is a consonant

at the end of a word. So that's within the wo

rd.

Now we could also think about the concept

position within a syllable. And we're going t

o do a lot of that in this course. When we thi

nk about constant position within a syllable,

we first need to take a word and break it up

into syllables. And then identify where a co

nsonant is in relation to that syllable within t

he word. So SIWI means syllable initial wor

d initial. Simply first consonant at the begin

ning of a syllable that's at the beginning of a

word. And I'll give you an example coming

up.

Syllable initial word within, and that means

it begins a syllable, but that syllable begins i

n the middle of a word. It's not the first sylla

ble of a word.

Syllable final word final is when the conson

ant comes at the end of a syllable that closes

off the word. It's the end of the word.

And syllable final word within is simply the

end of a syllable, but that is in the middle o

f the word still. And you'll see this more cle

arly very soon.

But before we get there, we could also think

about consonant position in relation to the v

owel. And so we describe consonants as bei

ng prevocalic if they come before a vowel.

So the first sound in a word, the first conson

ant in a word, is prevocalic. Postvocalic is f

ollowing a vowel. And so the final consona

nt in a word is postvocalic. And intervocalic

are consonants that are in the middle of a w

ord because they're surrounded by vowels.

So let me show you how this would look. W

e have two words here-- top and suitcase. T

op is simple, because it is a CVC, right? If

we think about our way of describing the co

nsonant and

vowel structure. And since top is CVC, the t

is syllable initial word initial. And the p is s

yllable final word final. Closes out the word

. Simple enough, right?

Now suitcase gets a little bit more complicat

ed, because there are two syllables in this co

mpound word-- suit case. And so s is syllabl

e initial word initial. The s at the end is sylla

ble final word final.

But these two phonemes in the middle are th

ought about differently. Now, if we only use

the terms initial, medial, and final they wou

ld both fall somewhere in the medial positio

n. But if we want to be a little more descript

ive and we break this down into syllables, t

closes out the first syllable. So it's syllable fi

nal word within. Whereas the k is syllable i

nitial, but it's word within because it's the be

ginning of the second syllable. And so k wo

uld be syllable initial word within. Right?

So this is a really nice, clear way to illustrat

e how to use consonant position, not only in

relation to the word, but also in relation to t

he syllable within which it falls.

Week 1 Page 4

uld be syllable initial word within. Right?

So this is a really nice, clear way to illustrat

e how to use consonant position, not only in

relation to the word, but also in relation to t

he syllable within which it falls.

Let's review the concept of distinctive featur

es. Distinctive features are phonetic charact

eristics of a group of sounds. And we use th

ese different features to distinguish sounds f

rom one another. And what that simply mea

ns is that we use phonemes to describe soun

ds differently. But we can take those phone

mes and break them down into a group of fe

atures that will distinguish those phonemes f

rom one another. It's really quite interesting.

So each phoneme is evaluated on a twovalue system. Either a distinctive feature is

present or it's absent. And we can use a plus

sign or a

1 to indicate whether it's present, a dash or a

0 to indicate if a feature is absent.

So let's first go through major class features.

And as

we're doing this, I'm going to guide you to t

hink about how they relate to the notions of

place manner voicing. Right? I

told you that before, and these ideas are goi

ng to keep coming back.

So when we think of major class features, w

e're specifying features that distinguish cons

onants and vowels, obstruents and sonorants

. And so first up is the notion of syllabic. Pl

us syllabic sounds are sounds that are going

to form the nucleus of a syllable. And so a v

owel or perhaps a syllabic consonant would

both be plus syllabic.

Now, this is different from the way we migh

t describe consonant sounds. And we'll use t

he term "consonantal" to describe sounds th

at are produced with a narrow constriction o

f the vocal tract, or perhaps even just a com

plete constriction in the vocal tract. So all c

onsonants are plus consonantal except for gl

ides, because they're more syllabic, kind of l

ike semivowels.

Sonorant. The word "sonorant" means that t

he vocal tract is set up to allow for spontane

ous voicing. And we know that

that only occurs for vowels-- so all vowels a

re sonorant-- for glides, liquids, and nasals.

And so when we think about these notions o

f syllabic or consonantal or sonorant, they re

late kind of to manner of production.

But there are also place features that we refe

r to when

we think of distinctive features. And these d

escribe the place of articulation. And so a di

stinctive feature, the labial feature, indicates

whether sounds are made at the level of the

lips and what might be going on there, speci

fically.

So for instance, plus round means there's pr

otrusion of the lips with some narrowing at t

he corners of the mouth. And plus labiodent

al infers that this sound is made with only o

ne lip. And so we can further distinguish so

unds from one another by indicating perhap

s whether they're plus labial or within that pl

us round or plus labiodental.

Another place feature is coronal. And coron

al sounds are made at or around the area of t

he alveolar ridge or even slightly farther for

ward. These are phonemes that are also ante

Week 1 Page 5

us round or plus labiodental.

Another place feature is coronal. And coron

al sounds are made at or around the area of t

he alveolar ridge or even slightly farther for

ward. These are phonemes that are also ante

rior in the oral cavity. And so place doesn't

only refer to maybe that precise place of arti

culation, but we do try to think more broadl

y about whether sounds are anterior as oppo

sed to further posterior.

So that's a segue into the term "dorsal," whe

re phonemes are made basically at the back

of the mouth. And this can be with the tong

ue body raised or tongue body lowered. And

so we use the terms plus back, plus high, or

even plus low to describe sounds that are m

ade in the back of the oral cavity and where

the tongue position might be as those sound

s are formed.

So consonantal and vocalic-- it refers and m

akes us think about where the constriction is

in the vocal tract. Or refers to, rather, not w

here, but the type of constriction in the voca

l tract, where for consonantal, there's a reall

y firm constriction. It might be complete or

narrow. And vocalic is much more open.

Continuant and interrupted are whether sou

nds are produced with continuous airflow m

ade in a steady state, as in F and

V, S and Z, or whether they're interrupted so

unds that have some kind of a blockage of a

ir, such as P

and B. And so this grouping, again, refers m

ore to manner than anything else.

Sonorant are sounds that allow the air strea

m to pass unimpeded, as I had mentioned ea

rlier. Vowels are sonorant. And we use this t

erm to distinguish from phonemes that have

more of a constriction. So vowels, glides, n

asals, and laterals and modified consonants,

these are all sonorant, because there's a mor

e open vocal tract. And we compare and con

trast that with sounds like stops, fricatives, a

nd affricates, that have some more firm clos

ure.

Strident phonemes. Strident sounds are nois

y sounds. And when a speaker is producing

a strident sound, there's some forcing of air t

hrough a small opening that results in that n

oisy quality. And so F and V, S

and Z, Sh, zh, tcha, are all examples of strid

ent phonemes. And just to clarify here, sh, z

h, tcha, the next phoneme is really the phon

eme ja, not the ya, just to clarify.

Lateral-- midline and air escapes laterally.

Nasals-- sounds in which air passes through

the nasal cavity. And then high versus low-again, coming back to tongue position.

And this is really important because when t

he tongue moves through the oral cavity, a h

igh sound is going to be differentiated from

a low sound. And we usually think of that n

eutral point as being the point somewhere in

the middle, where high would be above that

point for maybe a schwa. Low would be bel

ow that point for the schwa.

Also, more related to place is back versus a

nterior. And back refers to tongue position a

nd whether the phonemes are made with the

tongue retracted from that neutral position,

from that middle position, forward back. An

terior sounds that-- are made where the poin

t of constriction is anterior typically to the p

alatal point.

So "shuh" is a palatal phoneme. And we gen

erally think that sounds made in front of that

-- so that would include bilabials, labiodenta

ls, linguaalveolars, and linguadentals-- are all going t

o be anterior phonemes.

Just to get through a few more, coronal-- ro

Week 1 Page 6

-- so that would include bilabials, labiodenta

ls, linguaalveolars, and linguadentals-- are all going t

o be anterior phonemes.

Just to get through a few more, coronal-- ro

und, tense, and voiced. So for coronal, it's-again, think back to our place, manner, and

voicing descriptions. Coronal sounds are ma

de with the tongue blade raised typically in t

he lingua-alveolar area or around there.

Rounds sounds are made with the lips round

ed or protruded as an "oo" sound. And tense

phonemes are produced with a greater degr

ee of muscular tension. And we compare an

d contrast this with lax phonemes that don't

have that degree of tension.

And then, of course, voicing-- referring to s

ounds in which the vocal folds vibrate. So i

n some, these are features that you really jus

t need to sit through, review, and think abou

t. I realize that that material can be quite dry

. But the best way to make it functional is to

think about how these group of features rel

ate to place, manner, and voicing and which

feature links to which of those three.

And just to help you think about this a little

bit further, it could also help you to compar

e and contrast features. So for instance here,

if we are comparing P and Z-- very differen

t phonemes. But let's take a look at the featu

res associated with each and some, in partic

ular, features that distinguish them.

And so for one, we know they're both anteri

or phonemes, right? We could see that here- both anterior. But P

is labial. Z is not. And you can see that right

underneath anterior.

In terms of manner of production, they're qu

ite different because P is not continuant, but

z is. And then in terms of voicing, there are

also some pretty stark differences because

P is voiceless and Z is voiced.

And so while you can continue to go throug

h this on your own, the point is pretty clear.

And that is that we can take features and co

mpare and contrast them to one another.

Also important is to bring out your vowel q

uadrilateral. You have all seen this before. T

his is something that you have to really have

in your memory. And rather than telling yo

u to just go and memorize it, think about it r

eally conceptually.

And visualize the quadrilateral as the inside

of the oral cavity-- that's what it was design

ed to do-- where you've kind of got the front

of the oral cavity here. And this is the progr

ession from anterior to posterior. And so in

doing so, it will then quickly help you see h

ow "i" is a high front vowel. And that contra

sts with "ah," which is a low back vowel.

So earlier, when I was talking about high or

low in relation to the schwa, here's the schw

a. A high sound is produced above this. Lo

w sound is produced below. And that's a nic

e segue into distinctive features that describ

e vowels.

So vowels are going to be sonorant and voc

alic. They all are. But they'll differ in their c

avity features, as you just saw. So we have

high vowels, like "i," low vowels, like "ae,"

back vowels, and round vowels. And so imp

ortantly, those rounded vowels actually invo

lve lip rounding at the front of the oral cavit

y.

We talk about manner of articulation as tens

e versus lax. So some vowels involve more

muscular effort than others, as in "i." The ta

kehome message here is that there is certain pa

tterns that clearly distinguish vowels and co

nsonants. But when we are thinking about v

owels, remember, they're all voiced. They're

Week 1 Page 7

And tense phonemes are produced with a greater deg

ree of muscular tension. And we compare and contras

t this with lax phonemes that don't have that degree of

tension.

kehome message here is that there is certain pa

tterns that clearly distinguish vowels and co

nsonants. But when we are thinking about v

owels, remember, they're all voiced. They're

all nonnasalized. But they're influenced by what's a

round them, which is coarticulation.

And so, for instance, a nasal consonant next

to a vowel-- that vowel might take on some

slight nasal quality because of the surroundi

ng sounds. And that's a concept we'll get int

o more and more as we move through the co

urse.

Let's now define and describe the ter

m "speech sound disorders." Accordin

g to ASHA, the term "speech sound di

sorders" is now thought about as an u

mbrella term. You know, years ago, w

e often tried to distinguish-- and we st

ill do-- the difference between articula

tion disorders and phonological disor

ders. And so there's more consensus n

ow that there's this umbrella term call

ed "speech sound disorder" that really

encompasses both.

And so a speech sound disorder can o

ccur when speech intelligibility is infl

uenced by an issue with the way spee

ch is perceived; the actual motoric pro

duction of the sound, as in difficulty p

utting the lips together to produce a so

und-- and that's more articulation; the

phonological representation of a spee

ch sound or how sounds are combined

-- and that's the phonological or lingui

stic component; or maybe any combin

ation of the above.

And so we've really moved away fro

m entirely, completely separating arti

culation from phonology in that many

children have aspects of both type of

impairment. That's not to say that we

don't describe articulation of phonolo

gical issues, but more so acknowledge

that children can have elements of bo

th of these issues.

So a speech sound disorder can result

from a sensory impairment. When I ta

lked about the perceptual component,

I was talking about that sensory impai

rment. And we commonly see that in

hearing loss. Children can have a stru

Week 1 Page 8

from a sensory impairment. When I ta

lked about the perceptual component,

I was talking about that sensory impai

rment. And we commonly see that in

hearing loss. Children can have a stru

ctural impairment. Perhaps there's

a repaired lip, cleft lip, or repaired cle

ft palate. That would involve a structu

ral defect that was impaired.

Children can also have a motor impair

ment, and perhaps this is a child diagn

osed with childhood apraxia of speech

. That type of child would have aspect

s of a motor impairment. We also, tho

ugh, do see children who are diagnose

d with a given syndrome or some type

of conditionrelated impairment. So children with

Down syndrome are known to have c

ertain characteristics that might under

lie their speech production difficulties

. And then, of course, children can ha

ve a phonological impairment.

And when we think of phonology, ph

onology more broadly is something th

at happens at a linguistic level, at a hi

gher level, and the way that speech so

unds are the linguistic representation f

or sounds and how sounds are combin

ed. And so if there's any impairment a

t that level, that would be a phonologi

cal impairment.

Now, into thinking about speech soun

d disorders, I take a subsystems appro

ach. And this simply means that we're

not only thinking about what happens

at an articulatory level, but we're thin

king about the relationship between th

e speech subsystems. What does that

mean? It simply means that when we

speak, we speak on exhalation.

And so the respiratory system is invol

ved. The airflow then moves through t

he phonatory system. And there may

be vibrations. So sounds may be voice

d. They may be left unvoiced. And th

en, that sound wave moves through th

e vocal tract. So it goes through the re

sonatory system and then lastly, the ar

ticulation system. So it's really critical

to think of how these systems work t

ogether to understand how speech is p

roduced.

When we think of children with speec

h sound disorders, we then come back

to trying to understand where is the l

evel of breakdown. Is it in terms of re

spiration, phonation, resonance, articu

lation, or some combination of these d

ifferent areas? But if we don't begin b

y thinking about how speech involves

these subsystems, we cannot then get

to the point where we can identify th

e level of breakdown.

And so in doing so, and thinking abou

t level of breakdown, we're going to b

egin looking at ideological factors. So

is the underlying reason for the speec

h sound disorder organic, which mean

s is the difficulty related to some kind

of a neurological issue, maybe a struc

tural problem or some other kind of p

hysical issue? Or is this a functional p

roblem where we don't really know w

hy the child's speech is deviating from

what we'd see in typically developing

kids. So moving forward, we're going

to clearly distinguish between these t

wo ideological groups.

Week 1 Page 9

egin looking at ideological factors. So

is the underlying reason for the speec

h sound disorder organic, which mean

s is the difficulty related to some kind

of a neurological issue, maybe a struc

tural problem or some other kind of p

hysical issue? Or is this a functional p

roblem where we don't really know w

hy the child's speech is deviating from

what we'd see in typically developing

kids. So moving forward, we're going

to clearly distinguish between these t

wo ideological groups.

Let's begin by discussing organic impairme

nt. Our first ideological group. And so broa

dly, we can think of three categories. Perce

ptual-- that sensory, primarily hearing. Stru

ctural-- where there's some type of structura

l deformity or structural deficit. And then m

otor, which relates to some kind of a motor

impairment. And there are a variety of diffe

rent types.

So perceptual. Hearing loss. Children can h

ave-- or any individual can have-- a range o

f hearing loss. A conductive hearing loss is

when there is some type of, perhaps a malfo

rmation or an obstruction in either the outer

ear, ear canal, tympanic membrane, or midd

le ear. These are not inner ear issues.

And so, what we commonly see in children

is otitis media, or ear infections. So children

are prone to ear infections. Those ear infect

ions can vary in terms of the length of time

the infection is existing, in terms of the seve

rity of the infection.

And so, the influence on perception and pro

duction can vary greatly. So, while certainly

otitis media is not the only conductive hear

ing loss-- there are others that are listed her

e-- it probably is the most common thing th

at we do see in children. And that's the reas

on why we, in our interview, we ask a num

ber of questions related to the presence of e

ar infections or any of these other issues list

ed here, and whether they've been resolved.

Sensorineural hearing loss. A sensorineural

hearing loss is, in contrast to conductive-- c

onductive is a hearing loss that technically c

ould be improved or reversed. Sensorineura

l hearing loss is something quite different. T

he onset can be before birth, at the time of b

irth, or after birth. The causes can be conge

nital or acquired.

And so, what's key here is that really the ag

e of onset. So for instance, if a child is born

with a sensorineural hearing loss, they've be

en missing that sensory input, that perceptu

al input, all through their development. And

this is different than, say, an adult, who beg

ins losing their hearing once they have acqu

ired language.

So again, the influence on perception and pr

oduction can vary a lot depending on the se

verity of the loss, the cause of the loss, as w

ell as the onset of the impairment.

More specifically, what are some characteri

stics of speech sound errors? Well, some thi

ngs might be very difficult for-- some distin

ctions might be very difficult for someone

with a sensorineural hearing loss to perceiv

e. So voicing distinctions, for instance. Or e

ven nasalization versus non nasalization.

And some of these errors can relate to the fr

Week 1 Page 10

ctions might be very difficult for someone

with a sensorineural hearing loss to perceiv

e. So voicing distinctions, for instance. Or e

ven nasalization versus non nasalization.

And some of these errors can relate to the fr

equency of the sounds being produced. So s

omeone with a high frequency hearing loss

might have difficulty producing sounds that

are of higher frequencies, such a certain fri

catives.

We also do see distortions related to resona

nce, or maybe vowel precision. Problems w

ith vowel duration. As well as addition of c

ertain sounds, such as vowels between cons

onants.

When we move into structural impairment,

this is also an area where what we see can v

ary widely. Children can have minor issues,

perhaps a malocclusion, which refers to ho

w the upper and lower dentition come toget

her. They could have missing teeth. Of cour

se, it's very common for children to lose the

ir deciduous teeth until their permanent teet

h come in.

But there are children where those teeth ma

y be missing much earlier. And that will rai

se a concern for speech production. There al

so can be issues-- minor issues-- related to t

ongue, tongue size, the size of

the lingua frenulum, which is the tissue und

erneath the tongue.

Now that varies quite a bit from major issue

s, such as cleft lip and palate, or maybe anot

her craniofacial anomaly. Without going int

o an incredible amount of detail, let's go thr

ough what this might look like.

A cleft lip is when parts of

the lip do not come together during fetal de

velopment. And this occurs very early in fet

al development. Similarly, in a cleft palate,

there's a failure of parts of the palate. The p

alatal shelves don't fuse normally during fet

al development. And children can also have

something called a submucous cleft palate,

where, in looking in the mouth, the tissue's t

here. But the palatal shelves never fused ab

ove the tissue. And so that can be deceiving

. In the end, they'll be marked impact on res

onance for sure. And likely for articulation.

And just to show you what this looks like,

we see here a cleft of the

lip that's unrepaired. And here, if you look r

ight next to it, what you're actually seeing is

an unrepaired cleft palate. And this portion

right here is the top of the nasal cavity. And

so this is a child who did not have their clef

t palate repaired.

And if you want to look at this in a little mo

re detail, you can even see some abnormalit

y in the lip, right? And so it looks like that l

ip may have been repaired earlier. Just as an

aside, cleft lip in the United States is comm

only repaired around three months of age, t

he

palate around 12 months of age. And those

ages do vary depending on the site.

And a submucous cleft palate, as I mentione

d before, it can be difficult to see. But there

are some telltale signs, or signs that we nee

d to look into this further. One is a bifid uvu

la. And if you look at the uvula in the pictur

e, you'll see how it's split in two. That's a bi

fid uvula. This is pretty marked. But this ca

n also be a small indentation.

We could also see a notch in the hard palate

, or zona pellucida, which is an abnormal or

ientation of the soft palate musculature. An

d it causes the middle of the velum, as you s

ee here, to be thin and kind of bluish in colo

r. Specifically right there.

Now how does this all impact speech produ

Week 1 Page 11

ientation of the soft palate musculature. An

d it causes the middle of the velum, as you s

ee here, to be thin and kind of bluish in colo

r. Specifically right there.

Now how does this all impact speech produ

ction? It can, in a mild way all the way to se

vere way in terms of arctic and resonance.

What are some things we do see? We can se

e our obligatory errors. Meaning these are e

rrors that are related to the impairment such

as nasal emission, which is sort of sound co

ming, or the sound wave coming out of the

nasal cavity, reduced intraoral air pressure.

And it could also involve phoneme distortio

ns, visual distortions like facial grimacing

while producing speech.

These errors are often difficult to change wi

th therapy. We do, though, see compensator

y errors. Now when I use the term compens

atory, I mean it in sort of, not compensatory

in a positive way. These are learned devian

t patterns that persist after surgery, but can

be improved with treatment.

And of course, we don't want to forget that

children with submucous cleft palate, can al

so have developmental speech errors, just li

ke any other child. They might have a latera

l lisp or a phonological issue.

Now there are a few other types of motor i

mpairment. One is dysarthria, and that relat

es from neuromuscular impairment. And so

we most commonly link dysarthria, or see d

ysarthria in children with cerebral palsy.

So recall how I brought up the speech subsy

stems. And this is so important to think abo

ut with children with motor impairment, be

cause it's likely that there'll be a breakdown

across several subsystems. And so, what we

do see are that there can be difficulties in c

hildren with dysarthria, in respiration, in ph

onation, articulation, resonance, as well as i

n prosody.

But the characteristics are going to vary dep

ending on the type of dysarthria, and of cou

rse, depending on the severity of impairmen

t. A child could have mild dysarthria rangin

g all the way to severe dysarthria and compl

ete unintelligibility.

Briefly though, there are several types of dy

sarthria. I'll just outline them here for you a

nd point out the main characteristics. Flacci

d dysarthria, which is tied to a lower motor

neurolesion, commonly associated with a la

ck of muscle tone and some weakness. And

you can see how there's a breakdown in ma

ny areas. Hyper nasality, so that relates to re

sonance. Imprecise consonants. That relates

to articulation. Monotone, which is prosod

y. Nasal emission, which is resonance. It

can also be articulation. And then breathine

ss, which is phonation. So I think that's a re

ally clear example of how we could have a

breakdown at different levels.

Spastic dysarthria, though, is more tied to a

n upper motor neuron lesion further up in th

e production mechanism, further in the brai

n. And resulting in spasticity, weakness, a li

mited range of movement, and

an array of speech production difficulties fr

om imprecise articulation to harsh voice str

ained phonation, and so on.

And then lastly ataxic dysarthria is linked to

cerebellar-- damage to the cerebellar area.

We often see articulation or prosodic errors.

We can also see increased speech rate and

problems with loudness and pitch variabilit

y.

And so, this is really just a very brief overvi

ew as we do cover this content in different c

ourses.

And the last piece here is Childhood Apraxi

Week 1 Page 12

y.

And so, this is really just a very brief overvi

ew as we do cover this content in different c

ourses.

And the last piece here is Childhood Apraxi

a Speech. So, children who demonstrate mo

tor deficits, children with CAS, have motor

deficits. But there is often the absence of a c

lear neuro motor sign.

And so we describe how there's a deficit in

praxis, which is the ability to select, plan, or

ganize, and initiate movement. It's an aware

ness of where structures are during a move

ment. And so, there's consensus now, throu

gh ASHA and in the literature, that CAS is

a real disorder. It's a separate disorder from

an articulation impairment. It isn't simply a

severe articulation impairment. It's a motor

speech impairment.

And according to the ASHA

position statement from 2007, there are thre

e characteristics commonly associated with

CAS. They are inconsistent errors on conso

nants and vowels, lengthened and disrupted

coarticulatory transitions-- and I'll explain

what that means in a moment-- and inappro

priate prosody.

Now children's CAS can have other issues a

s well. And I'll explain that soon as well. Bu

t but these are three things that we first look

for. Inconsistent errors. I highlight this bec

ause inconsistent errors can take on several

different meanings. In relation to CAS, we t

hink of inconsistent errors on the same wor

d produced several different times. And so,

the word cat could be produced as tat, gat, o

r at. Three errors, but three different errors.

And that's atypical.

Disrupted coarticulatory transition is simply

difficulty moving from one phoneme to an

other. And so, the child might be able to pro

duce a kuh sound, but can't nicely sequence

that kuh with the next vowel, and or that vo

wel with the next consonant. So that breakd

own and sequencing can mean that the vow

el

is distorted, that the vowel's prolonged, may

be there's a voicing error in the consonant, a

nd so on.

And then inappropriate prosody. And this o

ften presents as equal stress. Children sound

ing very robotic. Like, we do, though, can s

ee-- we may also see inaccurate lexical or in

accurate phrasal stress. Lexical stress, whic

h is at the word level. Phrasal stress which i

s at the phrase level.

And then, lastly, there are additional charact

eristics of CAS. I mentioned how that ASH

A position statement highlights those three

components. But to me, criteria for CAS, w

e also look for, perhaps at least four of these

other characteristics. And that could be arti

culate groping, which is a struggle to produ

cing articulatory sounds. Problems ordering

sounds, syllables, and morphemes and wor

ds. Vowel errors, commonly seen as vowel

distortions. Errors in timing. That can relate

to voicing. That might relate to nasalization

. Omissions, which is leaving sounds out. D

istortions is distorting consonants, or perhap

s distorting vowels. And so on.

But ultimately, what we do see are that chil

dren with CAS tend to make very slow prog

ress in treatment. And that have difficulty w

ith sounds that increase as length and compl

exity increases. And we'll learn more about

this moving forward.

While an organic impairment has a cl

ear ideological component, a function

al impairment does not. So we'll use t

Week 1 Page 13

Up to this point, we've discussed primarily

disorders of speech sound production or er

rors in speech production. And those areas

can take different forms. When we think of

those errors as motor, we refer to them as

phonetic errors. In contrast, children can al

so have phonological errors. And so when

we're thinking about the actual diagnosis,

we can consider the difference between a p

honetic versus a phonological disorder. Re

call that these can both be contained under

the umbrella term "speech sound disorder.

"

So phonetics is, as a review, the physiologi

cal, physical characteristics of speech prod

uction. And when we talk about phonetic e

rrors, we primarily relate to placement or v

oicing issues. In contrast, phonology is lin

guistic. And so a phonological error refers

to a change in a sound class or the use of p

erhaps-- or alteration in the use of a produc

tion rule or a phonological rule.

Week 1 Page 14

While an organic impairment has a cl

ear ideological component, a function

al impairment does not. So we'll use t

he term functional impairment when

we've ruled out other issues in a trial.

So when structure and hearing acuity

and their physical systems appear to b

e normal, and so the cause of the imp

airment really can't be determined.

Most phonological impairments fall i

nto this category. And so, what's reall

y key with these children is that we as

sess clearly what we can assess, mean

ing we're sure that structure is intact b

y performing a comprehensive oral pe

ripheral exam. And children with spe

ech difficulties have had a comprehen

sive complete audiological evaluation

to rule out those elements. So once w

e've done that, we may determine that

the etiology is functional.

And so, broadly, when we think about

phonological delay or phonological d

isorder, we're trying to understand the

speech production difficulties in relat

ion to typical speech development. A

nd so we commonly use the term dela

y to refer to a situation where children

are using phonological patterns that

we see in typical speech development

. So for instance, a child who's four m

ay be producing speech patterns or ph

onological patterns that we might see

in a two-year-old, such

as dropping the ends of words, droppi

ng the final consonant of a word, or d

ropping the unstressed syllable in a w

ord.

In contrast, we use the term phonolog

ical disorder to describe processes or

patterns that aren't typically seen in sp

eech development. So these are nonde

velopmental patterns. For instance, a

child who overuses glottalization, that

's not something we typically expect t

o see in young children. So if we do s

ee a child overusing glottalization, tha

t might be a child who perhaps may b

e displaying a phonological disorder a

s opposed to a phonological delay.

Along those lines of thinking, we also

think about children falling into more

of a phonological disorder where the

y're using patterns perhaps that are m

ore complex, later developing sounds

or phonemes and not using earlier sou

nds. So children who have affricates i

n their phonetic inventory but are still

not producing bilabial phonemes acc

urately, that's the type of pattern that

might align with a phonological disor

der.

oicing issues. In contrast, phonology is lin

guistic. And so a phonological error refers

to a change in a sound class or the use of p

erhaps-- or alteration in the use of a produc

tion rule or a phonological rule.

And in many cases, or in some cases, whe

n children display phonological or otherwi

se called phonemic errors, they may also n

ot distinguish between phonemes or produ

ce different forms of phonemes. For exam

ple, a child might overuse a phoneme like

D to represent a variety of other phonemes

, so D would be used to also represent T, S

, and Z. In such cases, we would say that t

he child may not have a phonological or p

honemic contrast between those sounds.

Along those lines of thinking, in a phoneti

c problem, the phonemic contrast is preser

ved, but we believe this to be more motorbased. And so when a phonemic contrast is

preserved, the child is producing two disti

nct forms for two different phonemes. Wit

h a phonemic or phonological error, there

can be difficulty using phonemes to differe

ntiate meaning, which is that loss of phone

mic contrast similar to the example I gave

you of a child over using D. Now, these iss

ues are rulebased, and so the child might actually have

difficulty with the linguistic rule that unde

rlies the production.

So how can we tell if a phonemic contrast

exists between phonemes, because there ar

e times where you're really not sure. Well,

we can do some minimal pair work. And

minimal pairs are when we have two word

s that-- or problems with phonemes where

those phonemes differ with respect to one

distinctive feature.

For instance, in "pie" and "bye," P and B a

re distinguished only with respect to the vo

icing feature. P is voiceless. B is voiced. S

o if I were questioning whether the child c

an perceive and produce the difference bet

ween P and B, I would use minimal pairs t

o explore that further. And through this co

urse, I will help you understand how to ex

plore that using minimal pair contrast.

Similarly, "mess"

and "met." S and T are distinguished with r

espect to the continuant feature. S is contin

uant, T is not. But they're both made in the

same place of articulation and with the sa

me voicing, meaning they're both unvoiced

. And so it's possible that rather than havin

g an S and a T in their phonological repres

entation, the child may only have T and m

ay use T to represent both S and T.

So if we look at some specific examples, w

e try to figure out whether a problem may

be more or phonological. In the example o

f a lateralized S, in lateralized S, the child i

s likely to have this lateralization problem

where air is escaping out of the sides of the

tongue, and that a variety of phonemes are

produced with this lateralized articulation

pattern. Such cases are likely to be phoneti

c, or more motor-based.

But in contrast, if a child is stopping or fro

nting-- so if S becomes T, that's a stopping

error. If K becomes T, that's a

fronting error. If we are going to see that t

hese errors happen with some regularity, w

e begin to believe that perhaps there might

be a phonological reason, that there might

be a problem with

a linguistic rule that might underlie that pat

tern.

The bottom line is, children can have phon

etic and phonological errors. We do try to i

dentify the type of error pattern. But quite

Week 1 Page 15

lateralized S, in lateralized S, the child is likely to have this late

ralization problem where air is escaping out of the sides of the t

ongue, and that a variety of phonemes are produced with this lat

eralized articulation pattern. Such cases are likely to be phoneti

c, or more motor-based

a linguistic rule that might underlie that pat

tern.

The bottom line is, children can have phon

etic and phonological errors. We do try to i

dentify the type of error pattern. But quite

often in treatment we do need to deal with

remediating both types of errors.

So if we think back to the case study, that i

s similar to what we've seen before, similar

in age, once we understand and we're eval

uating a child, we want to really explore th

eir history a little bit more and then think a

bout how that relates to the way they're pre

senting currently. So in this little boy who'

s four, he is aware of

his speech difficulties, which is quite inter

esting. The teacher reports that he's teased

in school, so regardless of-- before we eve

n see him, we know that communication is

a problem here, that it's going to need to b

e addressed.

We know there's a significant family histor

y, because there are older siblings and both

have had speech and language issues. And

we also know that this child has not been

seen by a speech language pathologist, so t

here's no prior diagnosis at this point.

But when we look further into speech patte

rns based on the single word testing, we fi

nd that the child is deleting phonemes at th

e ends of words and fronting velars. And w

hat we want to do in a speech sample is to

analyze that further. So deleting phonemes

in the final word position could be a phon

ological process or a phonological pattern.

But we wouldn't know that unless we dove

deeper. Same with fronting of velars.

And so in the speech sample, I'm really goi

ng to look more deeply at this. And we not

ice that the child is consistent in the way th

at final consonants are deleted. Also has a

problem with consonant clusters being red

uced to one consonant, and continues to ha

ve problems with velars where they're bein

g fronted and voiced and a preference for

D.

So this profile seems to align with the desc

ription of a phonological impairment. Why

? Because there may be issues that are ling

uistically based that occur with some regul

arity that underlie the way the child is sim

plifying or reducing phoneme production.

And so we would through our relational an

alysis explore this further. And moving for

ward, I'll actually explain to you how to id

entify these phonological processes with gr

eater clarity.

Week 1 Page 16

c, or more motor-based

As clinicians, your perceptual jud

gments are going to play an impor

tant role in how you think about i

mpaired speech. And so judgment

s of speech intelligibility are impo

rtant to consider.

So first, we rely on qualitative jud

gments. There are many ways in

which we can quantify speech. Bu

t it all comes back to how speech

sounds to the listener. So the clini

cian's perception of how understa

ndable a child's speech is-- perhap

s parent's perspective, teacher's pe

rspective, the way in which a chil

d is perceived, and how understan

dable they are is really critical. An

d so, at the level of the clinician,

we will make these judgments in s

everal different ways.

We will judge the intelligibility of

words, phrases, sentences, or con

nected speech. Recall that we thin

k about coarticulation, the longer t

he utterance, the more there is a se

We will judge the intelligibility of

words, phrases, sentences, or con

nected speech. Recall that we thin

k about coarticulation, the longer t

he utterance, the more there is a se

quence amongst the articulators a

nd the speech subsystems. So we

might expect to see intelligibility

drop as children move from words

to connected speech. And so it's c

ritical to always include a judgme

nt of connected speech.

And we'll come to this point over

and over again. We would never

want to rely on basing our judgme

nt of intelligibility only on single

words alone. And then, so those ra

tings can take different forms. The

y can be in the form of excellent,

good, fair, poor. We also use ratin

gs in between that like good to fai

r, or fair to poor. But it's based on

our perceptions.

Now, we compare that with a qua

ntitative judgment. And this mean

s that we'd be measuring some asp

ect of speech production and com

paring it to a rating scale. This is c

ommonly done, probably most co

mmonly done, in terms of content

accuracy, but it also can be looked

at with wholeword accuracy. And so the most c

ommon way to do this is through

an index called the percent conson

ant correct. And so this was a mea

sure that was first described by Sh

riberg and Kwiatkowski in the '80

s.

Shriberg has since revised this me

tric in several different ways. But

we're really going to use the most

basic form. And that involves dete

rmining the number of consonants

that are produced correctly, comp

aring it to the total number of con

sonants, and multiplying by 100.

For example, if we had a speech s

ample that involved 100 consonan

ts and 75 were produced correctly,

then the Percent Consonant corre

ct would be 75%. But that's just a

number.

And in a few moments, I'll explai

n how to interpret that number. W

hat's important, though, is to think

about, following some guidelines,

what to score, what not to score.

And we will basically score every

sound the child is producing exce

pt for syllable and word repetition

s.

Meaning that, if you're determinin

g the PCC from a speech sample i

n which the child's playing with th

e car, and they've repeated the wo

rd car throughout that play scenari

o 10 times, you would only count

it once unless the child

has changed production of that wo

rd and has had several renditions

of that word.

Back to the score, what do we do

with that score. So you recall that

the example I gave you resulted in

a rating of 75%. This simply mea

ns that the child would fall within

the mild to moderate rating of spe

ech intelligibility, so the 65% to 8

5% range that's shown here. So thi

s is really important that when we

Week 1 Page 17

ns that the child would fall within

the mild to moderate rating of spe

ech intelligibility, so the 65% to 8

5% range that's shown here. So thi

s is really important that when we

come up with this percentage of p

ercent continent correct, that we r

elate it

to the severity rating scale, and th

at, this scale is an index of how in

telligible or unintelligible the chil

d may be.

The listening labs are a very fun and inter

esting component of this course. This is a

n opportunity for you to put your transcrip

tion skills to work and to learn how to des

cribe disordered speech. And so there'll be

components of these labs weaved into the

course, and I want to walk you through w

hat that's going to look like.

So first, the rationale is to give you the ch

ance to describe disordered speech. Most s

tudents don't have the chance to do this un

til they're sitting in front of a client, and it

does take skill and practice to get used to.

And so the labs will progress so that the tr

anscriptions will get a little more complic

ated over time.

So these weekly labs will be assigned. Yo

u're going to listen to a set of files and tran

scribe the productions using broad transcri

ption. So when we use broad transcription

, we're not using diacritics. I think it's best

to first really refine your skills using broa

d transcription first.

And so this is how it will happen. You're

going to assess a series of sound files and

a corresponding record sheet. You're then

going to transcribe productions using the I

PA-- the International Phonetic Alphabet- and transcribe them onto an Excel sheet t

hat you'll see here in a minute. And then y

ou're going to submit it. And so you'll the

n be able to access the answer key and the

score productions.

So just to orient you-- you're seeing here t

he English form of the word, the intended

form in IPA, the spoken form, and you're

going to put your transcription into that ca

tegory. But we're also going to look at a fe

w other things. So the intended word struc

ture is the consonant and vowel structure

of the intended form of the accurate produ

ction.

The spoken word structure is the structure

of what the child actually said. The numbe

r of consonants refers to the number of co

nsonants in the accurate form-- so how ma

ny consonants should have been produced

. And the column next to it that says numb

er of consonants correct is how many of th

Week 1 Page 18

er of consonants correct is how many of th

ose consonants were actually produced co

rrectly.

And then, lastly, the number of vowels col

umn refers to the number of vowels that w

ere in the target word that should have bee

n produced. The number vowels correct ar

e the vowels that were actually produced c

orrectly. So to just take a look at some of t

he-- listen and look at the transcription. Le

t's listen to the first word.

Housh.

So this word was produced incorrectly, an

d I would transcribe it like this. I'm using

brackets to illustrate that it's the productio

n form-- the producted form and "housh" t

o capture what the child actually produced

, and so you would fill this in the spoken

word column.

Next word-Widou.

Let's play that one more time.

Widou.

And so you would transcribe this as "wido

u." And you'll notice that there are some c

onsonants that are produced accurately but

other consonants that are missing. So if w

e move to the next slide, you'll see that I'v

e completed the form for you. And if we j

ust look at the word "house," how it was p

roduced is "housh".

The intended form was a CVC form, but t

he spoken word structure is the same. Eve

n though there was an error, it's still a con

sonant, vowel, consonant sequence. There

were two consonants in the intended prod

uction, but only one was produced correctl

y. And then there was only one vowel in t

he intended production, and that vowel wa

s produced correctly. And so you can go t

hrough and listen to each file, complete th

is chart, and you do have it as a reference j

ust to get you started.

But moving forward, you will not have th

e answer keys-- the answer key ahead of ti

me. So to sum this up, you'll open the for

m in Excel, you'll listen to the sound file, t

ranscribe an IPA on the Excel sheet, and I'

ll have some fonts shown in there to make

that a little bit easier for you to bring in.

You'll submit the transcriptions and then a

ccess the score sheet. And

I think you're going to find this is a great

way to get you started in listening to disor

dered speech.

Transcription Reminders for Listening Labs

There are different conventions for transcription of [r] in the final position

of a syllable.

In convention 1, rhotic vowels are transcribed as follows. Only the

centralized vowel is given r-coloring. When another vowel precedes /r/, a

final /r/ can be produced e.g., /ar/ in /kar/. CVC

Only the following rhotic vowels are used.

Rhotic vowels

• unstressed = /ɚ/ “paper”: /pɛɪpɚ/ CVCV

• stressed = /ɝ/ “bird”: /bɝd/ CVC

•

•

•

•

•

In convention 2, in addition to the rhotic vowels, we have rhotic dipthongs

at the end of a syllable. These rhotic diphthongs replace the vowel+final r.

Rhotic diphthongs

/ɪɚ/

“deer” : /dɪɚ/ CV

/ɔɚ/

“door”: /dɔɚ/ CV

/ɑɚ/

“dark” : /dɑɚk/

CVC

/ɛɚ/

“dare” : /dɛɚ/

CV

/uɚ/

“poor” : /puɚ/

CV

Also Recall:

Week 1 Page 19

- ɚ vs. ɝ

tiʧɚ (teacher) vs. pɝpl (purple)

Unstressed rhotic

Stressed rhotic

- ʌ vs. ə

ɛləfɪnt

vs.

kʌp

- ɚ vs. ɝ

tiʧɚ (teacher) vs. pɝpl (purple)

Unstressed rhotic

Stressed rhotic

- ʌ vs. ə

ɛləfɪnt

vs.

kʌp

Unstressed mid vowel Stressed mid vowel

PRACTICE: Identify the consonant positions in the following words:

Live Session 1

BOR Questions

1. What is a consonant cognate? Give an example?

2. When considering consonant position within a syllable—the

following acronyms are used: SIWI, SIWW, SFWF, SFWW—what do

these stand for?

3. When discussing Etiological Factors related to SSDs, we break them

up into Organic and Functional--define the 2.

4. How is PCC (Shriberg & Kwiatkowski, 1982) determined?

For a client to be considered in the mid-moderate range of

severity—what must their percentage be?

5. When feature contrasts differentiate one word from another—we

are talking about minimal pairs. Minimal pairs and consonant

cognates are different. Consonant cognates only differ by VOICING.

Week 1 Page 20

1. Necklace

a. /n/ (SIWI)

b. /k/ (SFWW)

c. /l/ (SIWW)

d. /s/ (SFWF)

2. Batman

a. /b/ (SIWI)

b. /t/ (SFWW)

c. /m/ (SIWW)

d. /n/ (SFWF)

3. Handbag

a. /h/ (SIWI)

b. /nd/ (SFWW)

c. /b/ (SIWW)

d. /g/ (SFWF)

4. Computer

a. /k/ (SIWI)

b. /m/ (SFWW)

c. /p/ (SIWW)

d. /t/ (SIWW)

5. Watches

a. /w/ (SIWI)

b. /ch/ SIWW)

c. /z/ (SFWF)

Thursday, January 21, 2021

7:17 PM

Speech Dev Week 1 Cheat Sheet:

Place/Manner/Voicing:

Place: The location of constriction

1. Bilabial: lips

2. Labio-dental: lips and teeth

3. Lingua-dental: tongue and teeth

4. Lingu-alveolar: tongue-alveolar ridge

5. Lingua-palatal: teeth and hard palate

6. Lingua-velar: tongue and soft palate

7. Glottal: glottis

Manner: Ways speakers block airflow through oral cavity using different types of constrictions

1. Stops: complete stoppage of air in vocal tract

2. Fricatives: narrow constriction that air passes through

3. Affricates: stoppage of airflow followed by a constriction

4. Nasals: coupling between oral and nasal cavities

5. Glide: gradually changing articulatory shape EX. WAH

6. Lateral: lingua-alveolar closure at midline but not at the sides of the tongue EX. UL

7. Rhotic: tongue bunched in the center of the oral cavity EX. ER

Voicing:

1. Voiceless: Produced with the vocal folds open so they do not vibrate during production of a sound.

2. Voiced: produced with the vocal folds approximated so they vibrate and produce noise or voicing.

ALL VOWELS ARE VOICED

CONSONANTS ARE VOICELESS OR VOICED

➢ The syllable is a small unit of speech with three components

1. Onset: consonant or cluster that initiates syllable

2. Nucleus/Peak: vowel or diphthong

3. Coda: consonant or cluster that follows nucleus

**Rime: nucleus + coda

within each box are cognate pairs. Cognates are sounds that are made in very much the same way but differ only with respect to voic

ing.

So let's look at p an b, for example. P and b are both bilabial stops. P is the voiceless of the pair. B is the voiced of the pair.

What's important to think about, though, is that how these sounds are made in almost exactly the same way. They are made in the sa

me way with the exception of the voicing being added or not. And so as your learning place manner of voicing, make use of this notio

n of cognate pairs, because it will help you group sounds together and make it easier to learn where they are.

Consonant Position:

Within a word

◦ Initial position

◦ Medial position

◦ Final position

Within a syllable

◦ SIWI: syllable initial word initial

◦ SIWW: syllable initial word within

◦ SFWF: syllable final word final

◦ SFWW: syllable final word within

In relation to the vowel

◦ Prevocalic (before a vowel)

◦ Postvocalic (after a vowel)

◦ Intervocalic (between vowels)

Week 1 Page 21

Week 1 Page 22

Phonological Processes Cheat Sheet:

Types of Processes:

1. Syllable structure processes

• Simplify the word or syllable structure

– Example: “banana” ➔ [nanə]

2. Substitution processes

• Changes affecting specific segments or segment types

– Example: “fin” ➔ [tɪn]

3. Assimilation processes

• Change a segment to becomes more similar to a surrounding segment

– Example: “kite” ➔ [kik]

Syllable Structure Processes:

1. Syllable deletion:

**Typically unstressed syllable deletion:

• Deletion of an unstressed syllable

• Examples: (hint: transcribe the adult form)

– “spaghetti” ➔ [gԑdi]

– “banana” ➔ [nænə]

– “microwave” ➔ [maɪkweɪv]

2. Consonant deletion

Typically affects initial or final consonant

Final consonant deletion: Deletion of the final consonant

Usually eliminated by 3 years

Examples:

– “cup” ➔ [kʌ]

– “dot” ➔ [da]

• Initial consonant deletion: Deletion of initial consonant Examples

– “cup” ➔

[ʌp]

– “mat” ➔

[æt]

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

3. Reduplication:

Partial or total repetition of a syllable or word

Most common in the phonology of the first 50 words

Usually eliminated by 3 years

Is it a strategy for producing multisyllabic words?

Examples:

– “water” ➔

[wawa]

– “dog”

➔

[dada]

– “wagon” ➔

[wawa]

4. Consonant cluster reduction/simplification

Total cluster reduction (TCR) vs. Partial cluster reduction (PCR)

• Total (TCR): involves deletion of all members of the cluster

• Partial (PCR): occurs when some of the cluster members are deleted but

others remain

– “snake” ➔ [neɪkeɪ] (PCR)

– “snake” ➔ [eɪk] (TCR)

– “plane” ➔ [peɪn] (PCR)

5. Cluster reduction and substitution

• Substitution for one member of a cluster and reduction.

– “scream” ➔ [stim]

– “street” ➔ [dim]

6. Epenthesis

• A process that results in the insertion of a vowel between two consonants

(usually schwa).

– Insertion of a vowel between two consonants functions to simplify

the cluster

• Example: “spoon” ➔ [səpun]

Week 1 Page 23

Buttercup= CV.CV.CVC

Comfortable= CVCC.CV.CVC

Palatal= CV.CV.CVC

• Example: “spoon” ➔ [səpun]

– Vowels may be added in word-final position

• Example: “color” ➔ [kʌlərə]

– Insertion of a consonant

• Example: “soap” ➔ [sΘop]

Substitution Processes: Involve sound changes where one sound class

replaces another class of sounds.

1. Stopping

• Replacing fricatives or affricates with stop consonants (Ingram, 1989)

• Example:

– Soap ➔ /toup/

– Mate ➔ /beɪt/

2. Fronting:

• Velar fronting: Replacing a velar consonant /k,g,ng/ by a more anterior

consonant (typically alveolar)

– Example: cake ➔ /teɪk/

• Palatal fronting (depalatalization): Substituting an alveolar fricative for a

palatal fricative OR an alveolar affricate for a palatal affricate

– Example: shoe ➔ /su/

3. Backing

• Replacing an anterior consonant with a posterior consonant

– Example: two ➔ /ku/

do ➔

/gu/

4. Stridency Deletion

• Deleting or replacing a strident sound [f,v,s,z,sh,ch] with a nonstrident

sound.

• Strident sounds are all affricates and fricatives, except “th” (includes

voiced/voiceless “th” and “h”)

• It is a process that is closely associated with stopping

– Example: soap ➔ /toup/

5. Deaffrication

• Substituting a fricative or stop for an affricate

• The fricative or stop may or may not be produced in the same place as the

affricate

• Usually suppressed by 4 years of age

– Example: jeep ➔ /zip/

cheese ➔

/diz/

6. Depalatalization

• Substituting an alveolar fricative for a palatal fricative

• Usually suppressed by 4 years of age

– Example: shed ➔ /sεd/

mash ➔ /mæd/

shave ➔ /zeɪd/

chew ➔ /tsu/

7. Gliding

• Replacing liquids with glides

• Very common in 3 and 3 ½ year old children

• Greater incidence of gliding for prevocalic /r/ than for /l/

– Example: red ➔ /wԑd/

leaf ➔

/jif/ OR /wif/

8. Vowelization/Vocalization

• Syllabic liquids or nasals are replaced with vowels

• The typical vowels are /o/ and /ʊ/.

– Example: bottle ➔ /baɾo:/

Paper ➔ /peɪpo/ - (also derhoticization)**

• When child does not delete other final consonants, vowelization is not

considered FCD.

Assimilation Processes: Altering a consonant phoneme to become more

similar to a surrounding phoneme

1. Velar assimilation:

• Alveolar consonant changes to become more like a velar consonant.

– Example: take ➔ /keɪk/

dog ➔ /gag/

2. Labial Assimilation

• A non-labial consonant is replaced with a labial consonant in a context

containing a labial consonant.

• Commonly see alveolars change to labials

– Example: knife ➔ /maif/

bone ➔

/bom/

3. Alveolar Assimilation

• Assimilation of a non-alveolar sound to an alveolar sound.

• The non-alveolar is influenced by another alveolar in the word.

– Examples: top ➔/tat/

Soup ➔

/sut/

Week 1 Page 24

4. Nasal Assimilation (manner change)

• Assimilation of a non-nasal to a nasal consonant

• Place of articulation may also be assimilated

– Example: gun ➔ /nʌn/

candy ➔

/næni/

5. Prevocalic voicing

• The change of a voiceless obstruent (fricative, affricate or stop) into a

voiced one when preceding a vowel within the same syllable

– Example: take ➔ /dek/

pen ➔ /bεn/

6. Final Consonant Devoicing (Post Vocalic Devoicing)

• Involves the devoicing of a voiced obstruent when it occurs at the end of a

syllable

• Example: made➔ /met/

dad ➔

/dæt/

7. Coalescence

• Features from 2 adjacent sounds combine to form one sound (total

assimilation)

– Example: Sweater ➔ /feɾɚ/

When do typically developing children stop producing phonological

processes??

{Smit & Hand (1997)}

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Assimilation

<3 yrs

FCD

<3 yrs

Stopping (initial fricatives & affricates) ~3½ yrs

Fronting of initial velars

4yrs

Cluster reduction (without s)

4yrs

Cluster reduction (with s)

5 yrs

Weak syllable deletion

5yrs

Gliding of initial liquids

7 yrs

Criteria for identifying the presence of a phonological process (McReynolds

& Elbert, 1981):

• One occurrence of a sound change does not signify the presence of a

process.

• Specific errors must have an opportunity to occur in at least four instances

• The error has to occur in at least 20% of the items that could be affected

by the process

• Example: If a child’s sample contained 20 words with final consonants, at

least four of the 20 words (20%) had to be produced without a final

consonant to list FCD as a process present in the child’s system.

Week 1 Page 25

Week 1 Page 26

Transcription Reminders for Listening Labs

There are different conventions for transcription of [r] in the final

position of a syllable.

In convention 1, rhotic vowels are transcribed as follows. Only the

centralized vowel is given r-coloring. When another vowel precedes /r/,

a final /r/ can be produced e.g., /ar/ in /kar/. CVC

Only the following rhotic vowels are used.

Rhotic vowels

• unstressed = /ɚ/ “paper”: /pɛɪpɚ/ CVCV

• stressed = /ɝ/ “bird”: /bɝd/ CVC

•

•

•

•

•

In convention 2, in addition to the rhotic vowels, we have rhotic

dipthongs at the end of a syllable. These rhotic diphthongs replace the

vowel+final r.

Rhotic diphthongs

/ɪɚ/

“deer” : /dɪɚ/ CV

/ɔɚ/

“door”: /dɔɚ/ CV

/ɑɚ/

“dark” : /dɑɚk/

CVC

/ɛɚ/

“dare” : /dɛɚ/

CV

/uɚ/

“poor” : /puɚ/

CV

Also Recall:

- ɚ vs. ɝ tiʧɚ (teacher) vs. pɝpl (purple)

Unstressed rhotic

Stressed rhotic

- ʌ vs. ə

ɛləfɪnt

vs.

kʌp

Unstressed mid vowel Stressed mid vowel

Week 1 Page 27

\

Week 1 Page 28

Week 1 Page 29

Printout

Thursday, January 28, 2021

5:55 PM

Week 1 Page 30

Week 1 Page 31

Week 1 Page 32

Week 1 Page 33

Week 1 Page 34

Week 1 Page 35

Week 1 Page 36

Week 1 Page 37

Week 1 Page 38

Week 1 Page 39

Week 1 Page 40

Week 1 Page 41

Week 1 Page 42

Week 1 Page 43

Week 1 Page 44

Printout

Tuesday, January 26, 2021

8:43 PM

Week 1 Page 45

Week 1 Page 46