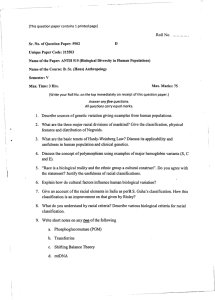

Constructing the Racial Hierarchy of Labor: The Role of Race in Occupational Prestige Judgments* Lauren Valentino , The Ohio State University Sociologists of culture are interested in processes of valuation, such as the way we value the division of labor. Typically measured through occupational prestige, prior research on this topic has largely neglected the potential role of race in the construction of the status hierarchy. This study asks whether and how race shapes judgments of occupational prestige, drawing on key insights from the sociology of race and ethnicity (Whiteness as a credential, strategic assimilation) to test key predictions about racial composition and a person’s own racial identity in this process. Combining data from the 2012 General Social Survey with federal administrative data, I find that Whiter jobs are, in fact, seen as more prestigious, even after taking into account an occupation’s level of required education/training, pay, industry, and gender composition. Further analyses demonstrate that this pattern is primarily driven by White and Asian raters and by raters with a college degree. Overall, then, this study indicates that the racial segregation of occupations impacts not only wages but also the status they confer to their incumbents. Introduction A central topic of study in the sociology of culture is “valuation”—how we make decisions about worth, merit, and value, and how these decisions are socially mediated (Brekhus and Ignatow 2019; Lamont 2012; Zelizer 2011; Zuckerman 2012). The fundamentally cultural process of valuation plays a critical role in the (re)production of social inequality and the construction of social hierarchies (Lamont, Beljean, and Clair 2014). In particular, the way we value labor and its divisions represents the defining feature of modern social stratification systems (Durkheim 1997; Hechter 1978). Yet, most research on the valuation of labor has focused on its material aspects—namely pay—while overlooking its symbolic aspects—such as status (Weber 1978). Sociologists have traditionally measured status by examining an occupation’s prestige—the perceived social standing of an occupation relative to others. However, much existing research on occupational prestige suffers from two limiting assumptions about the way people perceive and construct the occupational hierarchy: the materialist assumption, which presumes that only an occupation’s requirements and rewards determine where it falls in the hierarchy, and the homogeneity assumption, which presumes that all individuals view Sociological Inquiry, Vol. 92, No. 2, May 2022, 647–673 © 2021 Alpha Kappa Delta: The International Sociology Honor Society DOI: 10.1111/soin.12466 648 LAUREN VALENTINO the hierarchy the same way, regardless of their own social identities. Drawing on core insights from the sociology of race and ethnicity, I seek to challenge these two assumptions. I then derive and test three predictions about the role of race in judgments of occupational prestige, revealing how the racial hierarchy of labor is constructed in the United States. The prestige of a person’s occupation frames how others interact with them: the deference they are accorded, the benefit of the doubt they receive, the authority they can draw upon, and the power they have at their disposal. Furthermore, the effects of occupational prestige as status extend far beyond the workplace: occupation-derived status shapes health and well-being (Fujishiro, Xu, and Gong 2010), civic participation (Sobel 1993), marriage and family formation (Kalmijn 1994), and interactions with the criminal justice system (Lizotte 1978).1 Thus, it is critically important for social scientists to understand the individual, micro-level cultural process by which occupational prestige judgments are made. If race is part and parcel of the way we accord status to individuals on the basis of their profession, then that micro-level process can further entrench meso- and macro-level patterns of racial disparities in the contemporary United States. Challenging the Materialist Assumption Earlier perspectives on occupational prestige generally presumed that prestige is entirely determined by an occupation’s pay and educational/training requirement (Bukodi, Dex, and Goldthorpe 2011; Featherman and Hauser 1976; Hauser and Warren 1997; Lin and Xie 1988). This is what I term the materialist assumption: the notion that only the material factors associated with a job influence where people place it in the occupational status hierarchy. Emerging research has instead suggested the importance of non-material factors in occupational prestige judgments, such as the affective qualities of a job (Freeland and Hoey 2018; MacKinnon and Langford 1994), an occupation’s level of authority and autonomy (Zhou 2005), and the gender composition of an occupation (Valentino 2020). Race, however, has been largely missing from this picture. This is a surprising oversight given three important dynamics that are often highlighted by scholars of race and ethnicity: (1) the racial segregation of occupations, (2) the racialized nature of work, labor, and the occupational structure, and (3) the role of racial segregation and composition in other types of valuation processes. I now consider each of these dynamics in turn and their potential role in the construction of the status hierarchy of occupations. Although occupational racial segregation has declined since the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act which outlawed labor market discrimination, it has remained stubbornly persistent (Tomaskovic-Devey et al. 2006). As of 1988, CONSTRUCTING THE RACIAL HIERARCHY OF LABOR 649 29.3% of either Black or White workers would need to change jobs in order to achieve an equitable racial distribution across occupations (King 1992). The most recent analyses available indicate that Hispanic and Asian workers are even more likely than African Americans to work in racially segregated jobs (Alonso-Villar, Del Rio, and Gradin 2012), leading to what some scholars refer to as “brown-collar occupations”—poorly paid, unreliable jobs in which workers of color are overrepresented (Catanzarite 2000, 2002). Meanwhile, as of 2020, 93.2% of Fortune 500 CEOs are White, a figure that has hardly budged in the last two decades (Zweigenhaft 2021). Unsurprisingly, then, racial segregation in the labor market is linked to racial inequities in pay (Catanzarite 2000; Huffman and Cohen 2004; Tomaskovic-Devey 1993a). Given the relationship between racially segregated labor and material valuation (e.g., pay), we might also expect that there is a relationship between racially segregated labor and symbolic valuation (e.g., prestige). Furthermore, scholars of race and ethnicity have observed the tendency to associate certain jobs with particular ethnoracial groups. Maldonado (2006, 2009) finds that employers in the agriculture industry mentally categorize menial jobs using race essentialist ideas about Latinos/as and their suitedness for this type of work. In an audit study, Pager, Western, and Bonikowski (2009) find that employers steer Black and Latino applicants toward occupations with greater physical demands and lower customer service components than the ones they initially applied to, a process they term “race-based channeling.” Wingfield and Alston (2013) find evidence for the existence of “racial tasks,” specific types of labor that workers of color are often expected to fulfill in the workplace. Alegria (2019) finds that White women in the tech field are presumed to have strong social and soft skills, unlike men and women of color, and they are moved into managerial positions termed “glass step stools.” Given the persistent cultural associations between type of work and ethnoracial groups, we therefore should expect race to play a role in the way an occupation is evaluated. As TomaskovicDevey (1993b:6) argued, “the typical sex or race of a class of jobs in workplaces becomes a fundamental aspect of the jobs, influencing the work done as well as the organizational evaluation of the worth of the work.” Indeed, Ray (2019) has theorized that organizations produce and sustain a racialized hierarchy of jobs. Finally, the role of racial segregation in other processes—such as the valuation of neighborhoods and schools—reveals that racial composition plays a particularly important role in these judgments. For instance, a large body of work suggests that the racial composition of a neighborhood (both real and perceived)—in particular, its percentage of minority inhabitants—is an important determinant of how “good,” desirable, or safe that neighborhood is judged to be. Quillian and Pager (2001) find that perceptions of crime in Chicago, Seattle, and Baltimore are positively associated with the percentage of young Black 650 LAUREN VALENTINO men living in the neighborhood. Chiricos, McEntire, and Gertz (2001) have shown that the perceived proximity to both Black and Latino neighbors increased Floridians’ perceptions that they might become a crime victim. Sampson and Raudenbush (2004) find that a neighborhood’s racial composition predicts residents’ perceptions of disorder, both physical and social. Furthermore, St. John and Bates (1990) conducted a vignette study which revealed that hypothetical neighborhoods with higher proportions of Black residents—even with crime, cleanliness, housing quality, and other characteristics held constant —are judged as less desirable by Whites. Building on their work, Emerson, Yancey, and Chai (2001) find that White Americans are less likely to buy a home when a hypothetical neighborhood has a higher proportion of African American neighbors (but are unaffected by the proportion of Asian or Hispanic neighbors). Lastly, there is considerable evidence that the mere existence of Black and Latinx residents in a neighborhood leads to decreased property values and lower appraisals (Harris 1999; Howell and Korver-Glenn 2018, 2020). Racial composition of schools is also an important factor in how people perceive the quality of those schools and their willingness to enroll their children there. Goyette, Farrie, and Freely (2012) investigated this phenomenon among White residents of the Philadelphia area. They found that parents were more likely to perceive their child’s school quality as having declined when the number of Black students enrolled in the school increased—even when quantifiable measures of school quality showed no such decreases. In a vignette study, Billingham and Hunt (2016) asked White parents to consider where they would enroll their hypothetical five-year-old child for kindergarten. They found that the percent of students who are Black at the hypothetical neighborhood school was an important predictor of school choice, net of other manipulated school characteristics (e.g., state ranking, physical condition, and level of security). Overall, then, scholarship on racial inequalities has demonstrated the role of racial segregation in everyday instances of material and symbolic valuation. All three of these key insights from scholars of race and ethnicity point toward the potential role of race—specifically, racial composition—in shaping the hierarchy of jobs. Therefore, the first research question this study will answer is how does an occupation’s racial composition impact its perceived level of prestige? Only two studies have directly examined this question. Wu and Leffler (1992) found that racial composition is a more important determinant of occupational prestige than gender composition and that occupations composed of White men reap the highest prestige rewards. Nevertheless, their analysis only looked at 52 occupations, and did not adjust for other factors (such as education/training or pay) that are known to influence perceptions of prestige. We cannot know whether the apparent effect of racial composition on an occupation’s prestige is in fact driven by other occupational characteristics. CONSTRUCTING THE RACIAL HIERARCHY OF LABOR 651 More recently, Crawley (2014) conducted a survey experiment among undergraduates at a university and asked them to rate a hypothetical occupation in terms of status. She did not find that altering the racial composition of the hypothetical occupation impacted its perceived status. However, this approach required participants to make judgments about a single unfamiliar occupation— a much more unusual task than asking participants to make judgments about an unfamiliar neighborhood or school (something which most of us have done or will do in our lifetimes)—thereby limiting its external validity. Furthermore, it relied on a convenience sample of mostly White college students, limiting its generalizability to the broader U.S. population. Thus, we need data, which will allow us to examine judgments of prestige from a racially diverse sample about a broad range of occupations. What specifically might we expect the relationship between an occupation’s racial composition and prestige to look like? Research on racial segregation and pay indicates that predominantly White jobs tend to pay more, and in the domain of housing, predominantly White neighborhoods receive higher property appraisals. Beyond material valuation, Ray (2019) argues that Whiteness functions as a credential, legitimizing work-related hierarchies that place White work and workers at the top. Furthermore, the prior research on judgments and perceptions about neighborhood and schools overwhelmingly finds that Whiter neighborhoods and schools are seen as more desirable. I therefore expect that occupations with more White incumbents will be seen as more prestigious, net of other known occupation-level characteristics that shape prestige judgments (such as required level of education/training, pay, industry, and gender composition). Hypothesis 1 The percentage of White incumbents in an occupation is positively related to the occupation’s perceived prestige. Challenging the Homogeneity Assumption Much research on occupational prestige presumes that everyone views the occupational hierarchy the same way—regardless of their own social identity, such as what country they live in (Lin and Xie 1988; Tiryakian 1958; Treiman 1977) or what social groups they belong to (Hodge, Siegel, and Rossi 1964; Nakao and Treas 1992; Stevens and Featherman 1981). Yet, emerging research has highlighted the role of a person’s level of education (Lynn and Ellerbach 2017; Zhou 2005) and gender (Hinze 2005; Valentino 2020) in shaping the way they perceive the occupational hierarchy. Once again, however, the role of race in this process has gone largely unnoticed.2 652 LAUREN VALENTINO Therefore, the second research question this study will answer is does the impact of an occupation’s racial composition on occupational prestige judgments depend on a rater’s own race? In other words, should we expect that all racial groups rely on racial composition—and in the same way—when they are making judgments about where an occupation falls in the status hierarchy? Existing scholarship in race and ethnicity provides suggestive evidence that the answer to this question will be yes. Specifically, research on strategic assimilation and research on racial segregation in perceptions of neighborhoods and schools provide clues as to why we might expect this to be the case. I now briefly consider both of these strands of work. Strategic assimilation captures the idea that minoritized racial and ethnic groups may reject “standard” (often White) perceptions of the status hierarchy, and instead create alternatives that allow them to valorize their own cultural spaces and practices. Lacy (2004, 2007) finds that middle class African Americans view Black spaces as valuable sites for socialization, even if they live in a predominantly White neighborhood. Banks (2019) finds a similar process at work regarding Black donations to African American museums, as does Karam (2019) in terms of Muslim Americans and their parenting practices and Tatum and Browne (2019) vis-a-vis Dominican immigrants and their consumption patterns. Furthermore, different ethnoracial groups may hold different reference groups for what is considered high status. For instance, the late nineteenth- and early twentiethcentury occupation of Pullman porter was an exclusively Black job and was seen as solidly middle class occupation among the African American community at a time when they were outright barred from holding many other occupations (Frazier 1930). Strategic assimilation, along with the legacy of de jure racial segregation of occupations, suggests that racial and ethnic minorities do not automatically accept and espouse the prevailing status hierarchies of the White majority. Only four of the aforementioned studies of racial composition effects on perceptions of schools and housing were able to investigate the possibility of differences between individuals on the basis of racial identity.3 Three out of four found different relationships between racial composition and the outcome, depending on an individual’s own race. Quillian and Pager (2001) found that the effect of racial composition on perceptions of residential crime was stronger for White residents than Black residents. Chiricos McEntire and Gertz (2001) found that the (perceived) proportion of Black neighbors and Latino neighbors led White and Latino residents to perceive higher levels of crime victimization, but neither proportion impacted Black residents’ perceptions. Sampson and Raudenbush (2004) did not find a difference between Black residents and White residents in terms of racial composition’s relationship to perceived neighborhood disorder. Lastly, St. John and Bates (1990) found a negative, linear relationship for Whites between the percentage of Black residents and a CONSTRUCTING THE RACIAL HIERARCHY OF LABOR 653 neighborhood’s desirability, while for Black respondents, the relationship was non-linear (they preferred more Black neighbors, up to a point). The preponderance of evidence from this work and theories on strategic assimilation thus lead me to expect that there will be a dependency between a rater’s own race and the relationship between an occupation’s racial composition and prestige judgments. In particular, I predict that White raters will rely more on racial composition than raters of color in their assessment of an occupation’s prestige, net of all other occupational characteristics. Hypothesis 2 The relationship between the percentage of White incumbents in an occupation and an occupation’s perceived prestige depends on a rater’s race. Finally, the third research question of this study asks does education mitigate or enhance the relationship between an occupation’s racial composition and how prestigious it is judged to be? In the racial attitudes literature, two different perspectives point toward competing predictions. On the one hand, many studies find that people with lower levels of education have more prejudicial and less tolerant racial attitudes. Bobo and Kluegel (1993) find that education has a positive effect on a respondent’s support for race-targeted policies aimed at ameliorating inequality. Sniderman and Piazza (1993) find a strong negative relationship between number of years of schooling and number of negative characterizations about Black Americans. Bobo and Kluegel (1997) find that education has an overall negative effect on both “Jim Crow”-style racism and endorsement of Black stereotypes among Whites, and has a positive effect on Whites’ support for government helping improve the standard of living for Black Americans. Sears, Van Laar and Carillo (1997) similarly find that education is negatively related to anti-Black attitudes in three out of four datasets under consideration. In a review looking at 40 years of GSS data, Bobo, Charles and Krysan (2012) find lower education is consistently related to more negative racial attitudes among Whites. Overall, then, this group of studies indicates that education may serve to enlighten people to have more progressive racial views. This leads to the prediction that higher educated individuals should be less likely to draw on racial composition as a factor in their judgments of an occupation’s prestige. Hypothesis 3a The relationship between the percentage of White incumbents in an occupation and an occupation’s perceived prestige is weaker among higher educated raters as opposed to lower educated ones. 654 LAUREN VALENTINO On the other hand, a number of scholars have suggested that the espousal of progressive racial attitudes among the well-educated is a function of their socialization into the belief that racial prejudice is unseemly—but that this group may not necessarily truly hold racially progressive beliefs. Instead, these scholars argue the well-educated are simply better at hiding their prejudicial views, while also being more likely to espouse attitudes that seemingly justify their social group’s dominance. Jackman and Muha (1984:751) encapsulate this view based on their reading of GSS data: “We argue that dominant social groups routinely develop ideologies that legitimize and justify the status quo, and the well-educated members of these dominant groups are the most sophisticated practitioners of their group’s ideology.” Further evidence for this perspective can be found in the fact that there is no difference between educational groups in terms of their likelihood of showing racial bias on the Implicit Association Test (Greenwald and Krieger 2006). Most recently, Wodtke (2012) finds evidence of an attitude/policy divergence among the well-educated: Among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics, more education is related to a greater tendency to reject negative stereotypes about the outgroup and an increased awareness of discrimination against racial minorities, but more education is not related to an increased propensity to support racially progressive policies. In a related 2016 study that aimed to isolate the effect of intelligence, Wodtke (2016) concluded that Whites with high verbal ability are less likely to report prejudicial attitudes toward minorities and more likely to support racial equality in principle, but are not more likely to support policies promoting racial equality. Mueller (2017, 2020) argues for a theory of racial ignorance in which well-educated Whites adopt strategies to promote color-blind ideology while avoiding confronting the reality of racial inequality. Furthermore, acquiring more education has been shown to decrease Americans’ willingness to support equitable policies for wealth distribution (Bullock 2020). Specifically in regard to occupational prestige, Lynn and Ellerbach (2017) found that higher educated raters were more likely to draw on an occupation’s required level of education as a criterion when evaluating its prestige. Overall, then, this competing perspective would suggest that education is a means for ideological refinement and social closure, allowing individuals to become more discriminating in their ability to discern and defend hierarchies— of which racial composition is an important aspect. Hypothesis 3b The relationship between the percentage of White incumbents in an occupation and an occupation’s perceived prestige is stronger among higher educated raters as opposed to lower educated ones. CONSTRUCTING THE RACIAL HIERARCHY OF LABOR 655 Because most of these prior studies have focused exclusively on the relationship between education and racial attitudes among Whites, I will examine education effects separately for raters of different races.4 Data and Methodology To test these hypotheses, I draw on a linked dataset that incorporates occupational prestige judgments with the characteristics of those occupations. Prestige judgment data were collected as part of the 2012 General Social Survey module. Members of the 2008–2012 in-person portion of the rotating panel were asked to rate a ballot of 90 occupations as part of the 2012 data collection wave. Respondents were given one of twelve ballots with a set of 70 occupations unique to that ballot, while every ballot also contained 20 “core” occupations to rate. Respondents were instructed to rate each occupation on a scale of 1–9 in terms of its social standing, and ratings were not mutually exclusive, so respondents could place as many occupations as they liked at the same place on the scale, making it a true “rating” and not a “ranking.” Table 1 below shows the demographic characteristics of raters in the sample. I then linked the occupational prestige judgment data to information about the occupations being rated. These occupational data were assembled from Table 1 Demographic Characteristics of Raters Proportion Female Bachelor’s or higher White Black Hispanic Asian Working full-time South Age Household incomea a .550 .315 .791 .142 .026 .026 .471 .360 Mean SD 51.7 58109 16.3 42652 Min 22 0 Max 89 150000 Household income responses were provided in categories, so the category’s midpoint value was used in these calculations. 656 LAUREN VALENTINO various federal sources. The key independent variable, racial composition, was obtained from the U.S. Census’ Equal Employment Opportunity Report (2006– 2010), and is operationalized as the percentage of job incumbents who are White. Gender composition also comes from this report and is operationalized as the percentage of job incumbents who are female. Control variables include an occupation’s required level of education/training (obtained from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Network’s “job zone” index), an occupation’s mean pay (obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ 2012 employer reports), and an occupation’s industry (using the North American Industry Classification’s system). Table 2 below shows descriptive statistics for the dataset at the occupation level. Occupations with the lowest proportions of White incumbents include manicurist (46.3% White), English language translator (51.5% White), and barber (52.4% White). Occupations with among the highest proportions of White incumbents include cattle rancher (95.2% White), veterinarian (92.6% White), and meteorologist (91.1% White). Bivariate correlations between the occupation-level variations are shown in Table 3 below. Consistent with the prior literature on racial occupational segregation, we can see that the percentage of an occupation’s incumbents who are White is positively related to the occupation’s required education/training and mean pay. It is negatively related to the proportion of women in an occupation, which reiterates earlier findings about patterns of social closure and status composition that keep women and minorities siloed in particular jobs (Tomaskovic-Devey 1993b). Finally, we see some initial evidence to support Hypothesis 1: % White is positively related to prestige when averaged across all raters. Nevertheless, models that control for other occupational characteristics and that account for rater effects are necessary to isolate this effect. Therefore, I model how different occupational characteristics are used by different raters in the process of prestige judgments. I also account for raterspecific differences in scale usage and benchmarking, while simultaneously employing the full range of occupational data, by scaling prestige judgment to reflect person-specific deviations from their means. All regression models include the aforementioned occupational characteristics as controls (required education/training, mean pay, % female and % female squared, and industry categories), as well as ballot fixed effects. All coefficients are x-standardized to facilitate comparison of effect sizes across variables. All models also include robust standard errors, which are clustered at the individual rater level. Findings To test Hypothesis 1—whether racial composition has a significant and substantive effect on occupational prestige judgments—I test two models: one CONSTRUCTING THE RACIAL HIERARCHY OF LABOR 657 Table 2 Descriptive Statistics at the Occupation Level Education/training Pay % White % female Mean SD Min Max 2.85 52374 74.7 37.8 1.05 29440 9.2 26.6 1 18720 41.3 1.1 5 230540 95.2 97.7 Industry Proportion Architecture and engineering Arts, design, entertainment, sports, and media Building and grounds cleaning and maintenance Business and financial operations Community and social service Computer and mathematical Construction and extraction Education, training, and library Farming, fishing, and forestry Food preparation and serving-related Healthcare practitioners and technical Healthcare support Installation, maintenance, and repair Legal Life, physical, and social science Management Office and administrative support Personal care and service Production Protective service Sales and related Transportation and material moving .028 .039 .009 .046 .015 .022 .062 .022 .025 .022 .051 .017 .059 .007 .034 .094 .087 .040 .157 .034 .044 .078 that predicts prestige as a function of the occupational control variables only (education/training, mean pay, and gender composition)—Model 1; and one that adds the racial composition variable to the prediction equation—Model 2. As shown in Table 4 below, % White has a small but statistically significant effect on prestige. Furthermore, model fit improves substantially by AIC and 658 LAUREN VALENTINO Table 3 Zero-Order Correlations among Occupation-Level Variables Education/training Mean pay % White % female a Prestigea Education/training .747 .702 .433 .031 .734 .460 .144 Mean pay % White .485 .131 .260 Prestige rating is presented here as an average across all raters. Table 4 Models Without and With Racial Composition Model 1 Education/training Mean pay % Female % Female (squared) % White AIC BIC Log likelihood N .192*** .226*** .051*** .061*** 202892 203236 101409 80,518 (.008) (.008) (.006) (.004) Model 2 .183*** (.008) .221*** (.008) .029*** (.006) .048*** (.004) .037*** (.004) 202810.9 203164.1 101367.4 80,518 Note: Unit of analysis is individual-occupation rating. Lower values of AIC and BIC are preferred. *p < .05, **p < .01, and ***p < .001. Ballot fixed effects, industry controls, and intercepts not shown to conserve space (available upon request). Robust standard errors are clustered at the individual level. BIC standards when racial composition is included as a criterion in the judgment process. To give a better sense of the magnitude of this effect, I calculate relative sizes based on predicted prestige values at varying levels of racial composition benchmarked against another independent variable—mean pay. Increasing an occupation’s racial composition from 50% White to 90% White leads to a corresponding boost in prestige of .158 standard deviations—equivalent to the prestige boost that could be achieved by increasing an occupation’s pay by CONSTRUCTING THE RACIAL HIERARCHY OF LABOR 659 -.15 -.1 -.05 prestige 0 .05 .1 approximately $21,250. The impact of racial composition on prestige can also be illustrated from the predicted value plot, illustrated below in Figure 1. All in all, we see that occupations below the mean racial composition of 75% White are seen as less prestigious, while occupations above 75% are seen as more prestigious. This calculation takes into account effects of an occupation’s required education/training, pay, gender composition, and industry on prestige judgments. White workers made up 80% of the labor force in 2012 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2013), so the prestige boost for racial composition begins just short of this figure. This suggests that occupations that are Whiter than the prototypical job in terms of the labor market’s overall racial balance are those that are seen as the most prestigious. Hypothesis 1 is therefore supported: racial composition is indeed an important factor that people use when making judgments about occupational prestige, and Whiter jobs are generally seen as more prestigious. Next, I turn to Hypothesis 2, which examines whether the racial composition effect shown in Model 2 depends on a rater’s own race. To test this hypothesis, I introduce separate racial composition effects for raters depending 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 % White in occupation 80 85 Figure 1 Effect of Racial Composition on Prestige. 90 95 660 LAUREN VALENTINO on their own ethnoracial identity into the model. This is specified as Model 3 in Table 5 below. Results indicate that model fit is indeed improved by allowing the racial composition effect to depend on a rater’s own race (Model 3). This improvement is likely driven by the difference between White and Asian raters relative to raters of other races: Black and Hispanic raters do not grant a premium to Whiter jobs, while White and Asian raters do. This interpretation is bolstered by results of the Wald tests for differences in coefficients. The difference between White and Black raters in their usage of racial composition is significant (F(1, 985) = 6.13, p < .05). Asian raters are significantly different from the other racial groups in how they use % White in their occupational prestige judgments: White versus Asian (F(1, 985) = 22.49, p < .001), and Hispanic versus Asian (F(1, 985) = 11.39, p < .001). These differences can be summed up in Figure 2 below, which shows how raters of different ethnoracial backgrounds use racial composition differently when making prestige judgments (again, net of other controlled Table 5 Race-Specific Effects of Racial Composition on Prestige Education/training Mean pay % Female % Female (squared) % White % White (White rater) % White (Black rater) % White (Hispanic rater) % White (Asian rater) AIC BIC Log likelihood N Model 2 Model 3 .183*** (.008) .221*** (.008) –.029*** (.006) .048*** (.004) .037*** (.004) – – – – 202892 203236 101409 80,518 .183*** (.008) .220*** (.008) –.030*** (.006) .048*** (.004) – .041*** (.004) .002 (.014) .009 (.030) .123*** (.017) 202763.5 203154 101339.8 80,518 Note: Unit of analysis is individual-occupation rating. Lower values of AIC and BIC are preferred. *p < .05, **p < .01, and ***p < .001. Ballot fixed effects, industry controls, and intercepts not shown to conserve space (available upon request). Robust standard errors are clustered at the individual level. 661 -.6 -.4 -.2 prestige 0 .2 .4 CONSTRUCTING THE RACIAL HIERARCHY OF LABOR 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 % White in occupation 80 85 White rater Black rater Hispanic rater Asian rater 90 95 Figure 2 Race-Specific Effects of Racial Composition on Prestige. occupational characteristics). Hypothesis 2 is therefore partially supported: White raters and Asian raters rely on racial composition when assessing an occupation’s prestige, while Black and Hispanic raters do not. Finally, I test Hypotheses 3a and 3b by examining the possibility that raters of different educational backgrounds use the racial composition criterion differently. Because prior literature led me to expect that this relationship might be different within different racial categories, I conducted these educationspecific analyses within ethnoracial groups. For ease of interpretation, I have dichotomized the education variable into those who have a college degree or higher (31.4% of the sample) and those who do not have a college degree (68.6% of the sample). Results of this test are shown in Model 4 of Table 6 below. Model 4 specifies racial composition coefficients that are unique to each group of raters in terms of their race and education level.5 We see substantial improvement in model fit between Models 3 and 4, suggesting that the added complexity of race- and education-specific coefficients for racial composition is indeed warranted. 662 LAUREN VALENTINO Table 6 Race- and Education-Specific Effects of Racial Composition on Prestige Education/training Mean pay % Female % Female (squared) % White (White rater) % White (White, no college rater) % White (White, college rater) % White (Black rater) % White (Black, no college rater) % White (Black, college rater) % White (Hispanic rater) % White (Hispanic, no college rater) % White (Hispanic, college rater) % White (Asian rater) % White (Asian, no college rater) % White (Asian, college rater) AIC BIC Log likelihood N Model 3 Model 4 .183*** (.008) .220*** (.008) –.030*** (.006) .048*** (.004) .041*** (.004) – – .002 (.014) – – .009 (.030) – – .123*** (.017) – – 202892 203236 101409 80,518 .184*** (.008) .220*** (.008) –.030*** (.006) .048*** (.004) – .014* (.007) .093*** (.010) – –.017 (.015) .081* (.033) – .000 (.030) a – .117*** (.033) .126*** (.005) 202580.9 202999.3 101245.5 80,518 Note: Unit of analysis is individual-occupation rating. Lower values of AIC and BIC are preferred. *p < .05, **p < .01, and ***p < .001. Ballot fixed effects, industry controls, and intercepts not shown to conserve space (available upon request). Robust standard errors are clustered at the individual level. a Cell size is too small to produce reliable estimates, so this coefficient is omitted. Table 6 shows that there is substantial variation within racial groups—as well as between them—in terms of how they use the racial composition criterion. Among Whites, those without a college degree rely very little on racial composition, while those with a college degree place much greater weight on it. The difference between the education coefficients is significant (F(1, 985) = 35.37, p < .001). These effects are depicted in Figure 3 below. 663 -.4 -.2 prestige 0 .2 CONSTRUCTING THE RACIAL HIERARCHY OF LABOR 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 % White in occupation no college 80 85 90 95 college or higher Figure 3 Education-Specific Effects of Racial Composition on Prestige for White Raters. Among Black raters, those without a college degree do not see Whiter jobs as more prestigious. If anything, they may see Whiter jobs as less prestigious, although this coefficient is not significant. Black raters with a college degree do see Whiter jobs as more prestigious, although this effect is smaller in magnitude relative to White college-educated raters and Asian collegeeducated raters. The difference between the two education groups among Black raters is significant (F(1, 985) = 7.10, p < .01). These effects are depicted in Figure 4 below. Finally, in terms of Asian raters, those without a college degree do see Whiter jobs as more prestigious, but this effect is even larger for Asian raters with a college degree. Nevertheless, this difference in coefficients is not statistically significant (F(1, 985) = 0.06, p = .804). These effects are shown in Figure 5 below. Altogether, these results provide qualified support for Hypothesis 3b. For White and Black raters, having more education means that they are more likely to use the criterion of racial composition when making occupational prestige judgments, and this is especially true for White raters. White and Black raters LAUREN VALENTINO -.4 -.2 0 prestige .2 .4 664 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 % White in occupation no college 80 85 90 95 college or higher Figure 4 Education-Specific Effects of Racial Composition on Prestige for Black Raters. without a college degree only marginally (in the case of White raters) or do not at all (in the case of Black raters) consider the number of White incumbents in an occupation when assessing its prestige. For Asian raters, however, education has a less discernible effect: raters with and without a college degree both similarly rate Whiter jobs as more prestigious. Discussion and Conclusion We know surprisingly little about how race relates to the symbolic rewards of occupations: status—or, as it is commonly operationalized, occupational prestige. Although prior research has examined the impact of racial composition on judgments and perceptions about other institutions in American society, researchers have yet to fully investigate the impacts of racial composition on judgments and perceptions about the occupational structure. I have argued that this occurs because of two limiting assumptions about the way the hierarchy of labor is constructed: the assumption that it is materialist—implying individuals are color-blind as to the racial segregation and racialized nature of the occupational structure; and the assumption that is homogeneous—implying that a 665 -.6 -.4 -.2 prestige 0 .2 .4 CONSTRUCTING THE RACIAL HIERARCHY OF LABOR 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 % White in occupation no college 80 85 90 95 college or higher Figure 5 Education-Specific Effects of Racial Composition on Prestige for Asian Raters. person’s own identity (including their racial identity) has no bearing on the way they perceive the occupational hierarchy. The purpose of this study has been to shed light on this long-standing question by challenging these two assumptions, drawing on key insights from scholarship in race and ethnicity. The findings from this study demonstrate that racial composition is a salient cue that features prominently in people’s assessments of where an occupation falls in the status hierarchy. Much like when people make judgments about neighborhoods and schools, I find that the proportion of White workers in an occupation signals status—and the Whiter the occupation, the higher the status. It is notable that these effects are visible even when accounting for other known components of occupational prestige (such as a job’s required education/training, pay, gender composition, and industry). This finding aligns with prior work, which found that employers often associate certain ethnoracial groups with certain types of labor (Alegria 2019; Maldonado 2006, 2009; Pager et al. 2009; Wingfield and Alston 2013). It also provides evidence in favor of the theory of Whiteness as a credential (Ray 2019) and highlights the importance of processes through which organizations construct these hierarchies (Tomaskovic-Devey 1993b). 666 LAUREN VALENTINO However, the story is not so simple. Not everyone relies on the cue of racial composition when making occupational prestige judgments—or to be more precise, not everyone relies on it in the same way or to the same degree. White and Asian raters draw on the Whiteness of an occupation, rewarding jobs with more White workers in them. Pande and Drzewiecka (2016) find that some Asian Americans may engage in a process of strategic alignment with Whites, rather than a process of strategic assimilation; the findings here support that notion.6 Black and Hispanic raters, meanwhile, do not see Whiter jobs as more prestigious, in accordance with the strategic assimilation perspective. Part of these race differences in the usage of racial composition can be explained by educational differences between racial groups: When comparing collegeeducated White and Black raters, there is a roughly similar reliance on an occupation’s Whiteness when judging prestige, although Black college-educated raters are somewhat lower in the degree to which they reward occupational Whiteness relative to White college-educated raters. Among non-collegeeducated raters, however, race differences are quite prominent: Whites give a slight edge to Whiter occupations, and Asian raters reward Whiter occupations with a very large prestige premium; meanwhile, Black raters without a college degree do not reward Whiter occupations. Overall, then, these findings reinforce the importance of social factors— such as racial composition—in shaping occupational prestige judgments. Contra the materialist assumption, an occupation’s “pure” material factors—such as required education/training, pay, and industry—are not the only components of work that impact perceptions of status in the occupational structure. Results from this study also underline the fact that perceptual differences are not uniform across social groups, evidence against the homogeneity assumption: race acts as a filter that influences the way people perceive and order their social world. Finally, I have provided evidence in favor of the “ideological refinement as social closure” theory regarding education’s role in shaping attitudes. No matter a person’s race, having more education resulted in a rater relying more on the cue of racial composition as a way of organizing the occupational status hierarchy. Education in this case makes people more discriminating in how they construct the racial hierarchy of labor. Examining the role of racial composition in perceptions and judgments provides a relatively unobtrusive way of examining racial attitudes, an approach that is arguably less subject to the well-known social desirability bias that has plagued traditional survey research about race and ethnicity (Krumpal 2013).7 The extent to which people are consciously aware of the occupational prestige judgment-making process—especially their discursive beliefs about whether/ how they use criteria such as racial composition—represents an important next step in this line of research, and would have implications for dual-process CONSTRUCTING THE RACIAL HIERARCHY OF LABOR 667 theories of cognition and decision making (Miles, Charron-Chenier, and Schleifer 2019; Vaisey 2009). Nevertheless, the present study cannot distinguish between what social psychologists refer to as first-order and third-order beliefs: what social standing do I think a given occupation has, versus what social standing do I think most people think a given occupation has (see Correll et al. 2017; Melamed et al. 2019). Additional research collecting data on these two types of occupational status judgments is vital to disentangle whether these racial attitudes regarding status are truly held, or whether they may be a case of pluralistic ignorance (i.e., believing—perhaps incorrectly—that most other people think a given occupation is low status due to the preponderance of people of color who work in that job). The fact that racial composition is further inscribed in subjective perceptions of status such as occupational prestige suggests that race casts a longer shadow than has been previously acknowledged on status and its attendant outcomes. Gatekeepers use status to allocate material and symbolic resources in ways that can both mitigate and exacerbate existing inequities between ethnoracial groups. Because occupations predominated by people of color are symbolically devalued, this further restricts the mobility and life chances of the people working in these kinds of jobs. It is important for future work to understand how these racially infused prestige judgments impact concrete outcomes. For example, are people who work in occupations predominated by people of color less likely than those who work in Whiter jobs to be recommended for a higher starting salary or promotion, or to successfully obtain a mortgage or other loan? Future research, particularly that which uses a survey–experimental and/or field audit design, is critical for answering these questions. The pattern of rewarding Whiteness with prestige likely has important implications for social closure. Indeed, this may be a two-way process: Whites may reward predominantly White occupations with prestige, but they may also gatekeep predominantly White occupations on the basis of race in order to maintain the status privilege of those positions. Royster (2003) finds evidence for this type of gatekeeping among blue-collar workers, but future ethnographic field research should examine these micro-level processes of racial exclusion among white-collar workers and hiring managers. Overall, this study sheds new light on the processes of valuation of labor, a fundamental concern of cultural sociologists and scholars of inequality and stratification. Uniting insights from often-too-disparate fields such as cognitive sociology and the study of race and ethnicity (Brekhus, Brunsma, and Platts 2010), the present research illustrates the complex ways that race informs perceptions of status. By challenging the materialist and homogeneity assumptions of occupational prestige, this study has shown that the construction of the hierarchy of labor is profoundly racialized. 668 LAUREN VALENTINO Data Availability Statement The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research https://doi.org/10. 3886/ICPSR35478.v4. ENDNOTES *Please direct correspondence to Lauren Valentino, 1885 Neil Avenue Mall, Townshend Hall, Columbus, OH 43210-1132, USA; e-mail: valentino.60@osu.edu The author wishes to thank Chris Bail, Kieran Healy, Trish Homan, Jessi Streib, and Steve Vaisey for their invaluable feedback on this article. An earlier version of this work was presented at the “Jobs, Occupations, and Professions” session of the 2020 Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association. 1 Consider, for instance, the now-infamous case of Henry Louis Gates Jr. as he was harassed by police for entering his own home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Although we know that many Black men are unduly stopped and harassed by police in the United States, it was Gates’ status as a Harvard professor, which arguably sparked outrage and led to his invitation to the White House in an attempt to discuss the relationship between Black America and the police. If Gates had instead been a janitor at Harvard who was harassed for entering his own home, it is difficult to imagine that he would have made headlines and been invited for a beer with the President and Vice President of the United States. 2 Zhou (2005) finds that people of different races give differing weights to the role of knowledge, creativity, and authority in terms of how prestigious a job is, but does not examine racial variations in the role of racial composition in these perceptions. 3 Some of the research that has examined the role of racial composition in judgments has focused solely on White individuals (e.g., Billingham and Hunt 2016; Goyette et al. 2012), and for good reason: Whites generally control the majority of resources in terms of housing wealth and educational credentials in the United States, and so their perceptions and resultant choices are arguably more influential on the distribution of material and symbolic rewards in American society (Johnson and Shapiro 2003). At a more practical level, estimating rater-specific race effects can be prohibitive due to small cell sizes among ethnoracial minorities, particularly in small-N studies. 4 Among studies of this nature that did include racial minorities, there is some evidence of a strikingly different relationship between education and progressive racial attitudes between White vs. minority respondents. Bobo and Kluegel (1993) found that increased levels of education have a negative effect on progressive racial attitudes among Black Americans. 5 This specification assumes all other occupational characteristics are common across these subgroups—an assumption that allows for model fit comparisons, but one that merits a fuller investigation in a future study. 6 In their study of Asian Americans in California, Jimenez and Horowitz (2013) find that some of these individuals construct a hierarchy of academic achievement which places cultural associations regarding Asian-ness above Whites. 7 We also cannot know whether (in)accuracy in perceptions about racial composition drives the difference between lesser and more-educated raters. Perhaps higher educated raters are simply more aware of an occupation’s racial composition. This seems unlikely, however, given that it is lower educated individuals who are most likely to work in occupations with those of another race: CONSTRUCTING THE RACIAL HIERARCHY OF LABOR 669 Indeed, Table 3 above shows that there is a large positive correlation between the percentage of White workers in an occupation and the required education/training of that job. REFERENCES Alegria, Sharla. 2019. “Escalator or Step Stool? Gendered Labor and Token Processes in Tech Work.” Gender & Society 33(5):722–45. Alonso-Villar, Olga, Coral Del Rio, and Carlos Gradin. 2012. “The Extent of Occupational Segregation in the United States: Differences by Race, Ethnicity, and Gender.” Industrial Relations 51(2):179–212. Banks, Patricia A. 2019. “High Culture, Black Culture: Strategic Assimilation and Cultural Steering in Museum Philanthropy.” Journal of Consumer Culture 21(3):660–82. Billingham, Chase M. and Matthew O. Hunt. 2016. “School Racial Composition and Parental Choice: New Evidence on the Preferences of White Parents in the United States.” Sociology of Education 89(2):99–117. Bobo, Lawrence D., Camille Z. Charles, Maria Krysan, and Alicia D. Simmons. 2012. “The Real Record on Racial Attitudes.” Pp. 38–83 in Social Trends in American Life: Findings from the General Social Survey since 1972, edited by Peter V. Marsden. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Bobo, Lawrence and James R. Kluegel. 1993. “Opposition to Race-Targeting: Self-Interest, Stratification Ideology, or Racial Attitudes?” American Sociological Review 58(4):443–64. Bobo, Lawrence and James R. Kluegel. 1997. “Status, Ideology, and Dimensions of Whites’ Racial Beliefs and Attitudes: Progress and Stagnation.” Pp. 93–117 in Racial Attitudes in the 1990s: Continuity and Change, edited by Steven A. Tuch and Jack K. Martin. Westport, CT: Praeger. Brekhus, Wayne H., David L. Brunsma, Todd Platts, and Priya Dua. 2010. “On the Contributions of Cognitive Sociology to the Sociological Study of Race.” Sociology Compass 4(1):61–76. Brekhus, Wayne H. and Gabe Ignatow. 2019. The Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Sociology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Bukodi, Erzsebet, Shirley Dex, and John H. Goldthorpe. 2011. “The Conceptualisation and Measurement of Occupational Hierarchies: A Review, a Proposal and Some Illustrative Analyses.” Quality & Quantity 45(3):623–39. Bullock, John G. 2020. “Education and Attitudes toward Redistribution in the United States.” British Journal of Political Science 51, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123419000504 Catanzarite, Lisa. 2000. “Brown-Collar Jobs: Occupational Segregation and Earnings of RecentImmigrant Latinos.” Sociological Perspectives 43(1):45–75. Catanzarite, Lisa. 2002. “Dynamics of Segregation and Earnings in Brown-collar Occupations.” Work and Occupations 29(3):300–45. Chiricos, Ted, Ranee McEntire, and Marc Gertz. 2001. “Perceived Racial and Ethnic Composition of Neighborhood and Perceived Risk of Crime.” Social Problems 48(3):322–40. Correll, Shelley J., Cecilia L. Ridgeway, Ezra W. Zuckerman, Sharon Jank, Sara Jordan-Bloch, and Sandra Nakagawa. 2017. “It’s the Conventional Thought That Counts: How Third-Order Inference Produces Status Advantage.” American Sociological Review 82(2):297–327. Crawley, Donna. 2014. “Gender and Perceptions of Occupational Prestige: Changes Over 20 Years.” SAGE Open 4(1):1–11. Durkheim, Emile. 1997. The Division of Labor in Society. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. 670 LAUREN VALENTINO Emerson, Michael O., George Yancey, and Karen J. Chai. 2001. “Does Race Matter in Residential Segregation? Exploring the Preferences of White Americans.” American Sociological Review 66(6):922–35. Featherman, David L. and Robert M. Hauser. 1976. “Prestige or Socioeconomic Scales in the Study of Occupational Achievement?” Sociological Methods & Research 4(4):403–22. Frazier, E. Franklin. 1930. “Occupational Classes among Negroes in Cities.” American Journal of Sociology 35(5):718–38. Freeland, Robert E. and Jesse Hoey. 2018. “The Structure of Deference: Modeling Occupational Status Using Affect Control Theory.” American Sociological Review 83(2):243–77. Fujishiro, Kaori, Xu Jun, and Fang Gong. 2010. “What Does ‘Occupation’ Represent as an Indicator of Socioeconomic Status? Exploring Occupational Prestige and Health.” Social Science & Medicine 71(12):2100–107. Goyette, Kimberly A., Danielle Farrie, and Joshua Freely. 2012. “This School’s Gone Downhill: Racial Changes and Perceived School Quality among Whites.” Social Problems 59(2):155–76. Greenwald, Anthony G. and Linda Hamilton Krieger. 2006. “Implicit Bias: Scientific Foundations.” California Law Review 94(4):945–67. Harris, David R. 1999. “‘Property Values Drop When Blacks Move In, Because. . .’: Racial and Socioeconomic Determinants of Neighborhood Desirability.” American Sociological Review 64(3):461–79. Hauser, Robert M. and John Robert Warren. 1997. “Socioeconomic Indexes for Occupations: A Review, Update, and Critique.” Sociological Methodology 27(1):177–298. Hechter, Michael. 1978. “Group Formation and the Cultural Division of Labor.” American Journal of Sociology 84(2):293–318. Hinze, Susan W. 2005. “Gender and the Body of Medicine or at Least Some Parts: (Re) Constructing the Prestige Hierarchy of Medical Specialties.” The Sociological Quarterly 40 (2):217–39. Hodge, Robert W., Paul M. Siegel, and Peter H. Rossi. 1964. “Occupational Prestige in the United States, 1925–63.” American Journal of Sociology 70(3), 286–302. Howell, Junia and Elizabeth Korver-Glenn. 2018. “Neighborhoods, Race, and the Twenty-firstcentury Housing Appraisal Industry.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 4(4):473–90. Howell, Junia and Elizabeth Korver-Glenn. 2020. “The Increasing Effect of Neighborhood Racial Composition on Housing Values, 1980–2015.” Social Problems 68(4), 1–21. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/socpro/spaa033 Huffman, Matt L. and Philip N. Cohen. 2004. “Racial Wage Inequality: Job Segregation and Devaluation across U.S. Labor Markets.” American Journal of Sociology 109(4):902–36. Jackman, Mary R. and Michael J. Muha. 1984. “Education and Intergroup Attitudes: Moral Enlightenment, Superficial Democratic Commitment, or Ideological Refinement?” American Sociological Review 49(6):751–69. Jimenez, Tomas R. and Adam L. Horowitz. 2013. “When White is Just Alright: How Immigrants Redefine Achievement and Reconfigure the Ethnoracial Hierarchy.” American Sociological Review 78(5):849–71. Johnson, Heather Beth and Thomas M. Shapiro. 2003. “Good Neighborhoods, Good Schools: Race and the ‘Good Choices’ of White Families.” Pp. 173–88 in White Out: The Continuing Significance of Racism, edited by Ashley Woody Doane and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva. New York, NY: Routledge. Kalmijn, Matthijs. 1994. “Assortative Mating by Cultural and Economic Occupational Status.” American Journal of Sociology 100(2):422–52. Karam, Rebecca A. 2019. “Becoming America by Becoming Muslim: Strategic Assimilation among Second-Generation Muslim American Parents.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 43(2):390–409. CONSTRUCTING THE RACIAL HIERARCHY OF LABOR 671 King, Mary C. 1992. “Occupational Segregation by Race and Sex, 1940-88.” Monthly Labor Review 115(4), 30–42. Krumpal, Ivar. 2013. “Determinants of Social Desirability Bias in Sensitive Surveys: A Literature Review.” Quality & Quantity 47(4):2025–47. Lacy, Karyn R. 2004. “Black Spaces, Black Places: Strategic Assimilation and Identity Construction in Middle-Class Suburbia.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 27(6):908–30. Lacy, Karyn R. 2007. Blue-Chip Black: Race, Class, and Status in the New Black Middle Class. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Lamont, Michele. 2012. “Toward a Comparative Sociology of Valuation and Evaluation.” Annual Review of Sociology 38(1):201–21. Lamont, Michele, Stefan Beljean, and Matthew Clair. 2014. “What Is Missing? Cultural Processes and Causal Pathways to Inequality.” Socio-Economic Review 12(3):573–608. Lin, Nan and Wen Xie. 1988. “Occupational Prestige in Urban China.” American Journal of Sociology 93(4):793–832. Lizotte, Alan J. 1978. “Extra-Legal Factors in Chicago’s Criminal Courts: Testing the Conflict Model of Criminal Justice.” Social Problems 25(5):564–80. Lynn, Freda B. and George Ellerbach. 2017. “A Position with a View Educational Status and the Construction of the Occupational Hierarchy.” American Sociological Review 82(1):32–58. MacKinnon, Neil J. and Tom Langford. 1994. “The Meaning of Occupational Prestige Scores: A Social Psychological Analysis and Interpretation.” Sociological Quarterly 35(2):215–45. Maldonado, Marta Maria. 2006. “Racial Triangulation of Latino/a Workers by Agricultural Employers.” Human Organization 65(4):353–61. Maldonado, Marta Maria. 2009. “’It is their Nature to do Menial Labour’: The Racialization of ‘Latino/a Workers’ by Agricultural Employers.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32(6):1017–36. Melamed, David, Christopher W. Munn, Leanne Barry, Bradley Montgomery, and Oneya F. Okuwobi. 2019. “Status Characteristics, Implicit Bias, and the Production of Racial Inequality.” American Sociological Review 84(6):1013–36. Miles, Andrew, Rapha€el Charron-Chenier, and Cyrus Schleifer. 2019. “Measuring Automatic Cognition: Advancing Dual-Process Research in Sociology.” American Sociological Review 84(2):308–33. Mueller, Jennifer C. 2017. “Producing Colorblindness: Everyday Mechanisms of White Ignorance.” Social Problems 64(2):219–38. Mueller, Jennifer C. 2020. “Racial Ideology or Racial Ignorance? An Alternative Theory of Racial Cognition.” Sociological Theory 38(2):142–69. Nakao, Keiko and Judith Treas. 1992. “The 1989 Socioeconomic Index of Occupations: Construction from the 1989 Occupational Prestige Scores.” GSS Methodological Report No. 74. Pager, Devah, Bruce Western, and Bart Bonikowski. 2009. “Discrimination in a Low-Wage Labor Market a Field Experiment.” American Sociological Review 74(5):777–99. Pande, Somava and Jolanta A. Drzewiecka. 2016. “Racial Incorporation through Alignment with Whiteness.” Journal of International and Intercultural Communication 10(2):115–34. Quillian, Lincoln and Devah Pager. 2001. “Black Neighbors, Higher Crime? The Role of Racial Stereotypes in Evaluations of Neighborhood Crime.” American Journal of Sociology 107 (3):717–67. Ray, Victor. 2019. “A Theory of Racialized Organizations.” American Sociological Review 84 (1):26–53. Royster, Deirdre. 2003. Race and the Invisible Hand: How White Networks Exclude Black Men from Blue Collar Jobs. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. 672 LAUREN VALENTINO Sampson, Robert J. and Stephen W. Raudenbush. 2004. “Seeing Disorder: Neighborhood Stigma and the Social Construction of ‘Broken Windows’.” Social Psychology Quarterly 67(4):319– 42. Sears, David O., Colette Van Laar, Mary Carillo, and Rick Kosterman. 1997. “Is It Really Racism? The Origins of White Americans’ Opposition to Race-Targeted Policies.” The Public Opinion Quarterly 61(1):16–53. Sniderman, Paul M. and Thomas L. Piazza. 1993. The Scar of Race. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Sobel, Richard. 1993. “From Occupational Involvement to Political Participation: An Exploratory Analysis.” Political Behavior 15(4):339–53. St John, Craig and Nancy A. Bates. 1990. “Racial Composition and Neighborhood Evaluation.” Social Science Research 19(1):47–61. Stevens, Gillian and David L. Featherman. 1981. “A Revised Socioeconomic Index of Occupational Status.” Social Science Research 10(4):364–95. Tatum, Katharine and Irene Browne. 2019. “The Best of Both Worlds: One-Up Assimilation Strategies among Middle-Class Immigrants.” Poetics 75:101317. Tiryakian, Edward A. 1958. “The Prestige Evaluation of Occupations in an Under Developed Country: The Philippines.” American Journal of Sociology 63(4):390–99. Tomaskovic-Devey, Donald. 1993a. “The Gender and Race Composition of Jobs and the Male/ Female, White/Black Pay Gaps.” Social Forces 72(1):45–76. Tomaskovic-Devey, Donald. 1993b. Gender and Racial Inequality at Work: The Sources and Consequences of Job Segregation. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press, Cornell University. Tomaskovic-Devey, Donald, Catherine Zimmer, Kevin Stainback, Corre Robinson, Tiffany Taylor, and Tricia McTague. 2006. “Documenting Desegregation: Segregation in American Workplaces by Race, Ethnicity, and Sex, 966–2003.” American Sociological Review 71 (4):565–88. Treiman, Donald J. 1977. Occupational Prestige in Comparative Perspective. New York, NY: Academic Press. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2013. “Labor Force Characteristics by Race and Ethnicity, 2012.” Report #1044. <https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/race-and-ethnicity/archive/race_ethnicity_ 2012.pdf>. Accessed December 14, 2020. Vaisey, Stephen. 2009. “Motivation and Justification: A Dual-Process Model of Culture in Action.” American Journal of Sociology 114(6):1675–715. Valentino, Lauren. 2020. “The Segregation Premium: How Gender Shapes the Symbolic Valuation Process of Occupational Prestige Judgments.” Social Forces 99(1):31–58. Weber, Max. 1978. “Status Groups and Classes.” Pp. 302–9 in Economy and Society, edited by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Wingfield, Adia Harvey and Renee Skeete Alston. 2013. “Maintaining Hierarchies in Predominantly White Organizations: A Theory of Racial Tasks.” American Behavioral Scientist 58(2):274–87. Wodtke, Geoffrey T. 2012. “The Impact of Education on Intergroup Attitudes: A Multiracial Analysis.” Social Psychology Quarterly 75(1):80–106. Wodtke, Geoffrey T. 2016. “Are Smart People Less Racist? Verbal Ability, Anti-Black Prejudice, and the Principle-Policy Paradox.” Social Problems 63(1):21–45. Wu, Xu and Ann Leffler. 1992. “Gender and Race Effects on Occupational Prestige, Segregation, and Earnings.” Gender & Society 6(3):376–92. Zelizer, Viviana A. 2011. Economic Lives: How Culture Shapes the Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. CONSTRUCTING THE RACIAL HIERARCHY OF LABOR 673 Zhou, Xueguang. 2005. “The Institutional Logic of Occupational Prestige Ranking: Reconceptualization and Reanalyses.” American Journal of Sociology 111(1):90–140. Zuckerman, Ezra. 2012. “Construction, Concentration, and (Dis)Continuities in Social Valuations.” Annual Review of Sociology 38:223–45. Zweigenhaft, Richard L. 2021. “Diversity among Fortune 500 CEOs from 2000 to 2020: White Women, Hi-Tech South Asians, and Economically Privileged Multilingual Immigrants from Around the World.” Who Rules America. <https://whorulesamerica.ucsc.edu/power/diversity_ update_2020.html>. Accessed February 25, 2021.