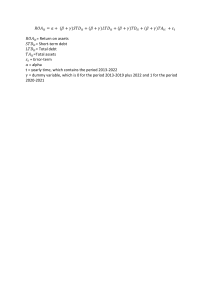

Advanced Valuation IB Questions Before We Begin… As I’ve always said, the TMT Banking Guides I’ve created are not meant to teach you the basics of investment banking generally. There are countless guides around (e.g., the classic 400 IB Questions Guide) that will cover the basic traditional accounting and valuation questions that will come up in your interviews. However, after completing the Telecom Guide, Media Guide, and Tech Guide I realized that I really should cover some of the most advanced accounting and valuation technicals you can get asked in an interview. This is because interviews have become much more difficult over the past few years; largely due to the fact that everyone prepares from the same set of old questions, so you need to figure out a way to differentiate between interviewees somehow. The way that interviewees are largely differentiated now is by: 1. Whether it seems like they have an impressive understanding of the coverage / industry group they’re applying to (or that they want to join after securing a generalist offer). 2. Whether they can answer more advanced accounting and valuation IB questions (some of which are outside the traditional guides that all interviewees are using to prepare). The Telecom Guide, Media Guide, and Tech Guide are aimed at addressing the first point listed above. They’ll help you quickly get up-to-speed quickly on each area of TMT and provide you with more information than you’d ever need to know, which will really make you stand out in an interview. The Advanced Accounting Guide and the Advanced Valuation Guide are aimed at addressing the second point listed above. These are the most advanced questions that are asked in interviews, many of which you most likely will not have seen before. To make things a bit more digestible, there are five distinct sections to this guide: DCF Questions, Enterprise Value and Equity Value Questions, Merger Model Questions, General Valuation Questions, and LBO Questions. In this Advanced Valuation Guide I’ve tried to not jump immediately into advanced questions, but rather spend a bit of them explaining conceptual questions (e.g., why we take cash off of EV) that I haven’t seen explained that well elsewhere. Finally, I’d just note that while all the questions in this guide are fair game to be asked in interview, but most of them are going to be rarer due to being more difficult (so don’t forget to review the more basic questions contained in the traditional guides). TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 1 The Purpose of These Guides… Remember that the reason why I created these guides is to try to help you be the most prepared candidate possible, not to give you the bare minimum. There will be a significant amount of information contained within the five guides in the members area that you’ve probably not been exposed to before, so it may be a touch overwhelming at first. If you find yourself getting a bit anxious about how underprepared you feel, just keep in mind that I’m trying to give you more TMT-specific information and advanced “traditional” questions than you’d ever need to know in an interview so that you can truly stand out. I’ve always found that you can somehow just tell when interviewees have a firm grasp on what a coverage group involves. It just comes across in an interview, either through their confidence or being able to talk at length about a certain nuance of TMT unprompted. I really enjoy explaining concepts and trying to distill relatively complex topics, so hopefully I’ve been able to do that through all of these guides. However, even if you just have a rough understanding of most of the questions contained in these guides trust me that you’ll still stand out from the rest. Also, remember that getting a basic interview question wrong may tank your interview. But getting an advanced question wrong isn’t the end of the world – especially if you can conceptually explain what’s going on, but just forget a step so end up with the wrong answer. With all that said, let’s get started… TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 2 DCF Questions Note: Keep in mind that I’m going to go over just the most important and / or difficult questions that could be asked on DCFs in an interview – you still need to know the basic questions! 1. Walk me through how to get unlevered and levered FCF starting from revenue. This obviously is a pretty basic question, but it’s important enough that I figured I’d include it to start things off. To get unlevered FCF, we’ll start with revenue and then take off COGS to get our gross profit. Then we’ll take off our operating expenses to get down to EBIT. We’ll multiple this by (1-t), where t is our tax rate, and then add back depreciation, amortization, and other non-cash items. We’ll then subtract any increase in NWC (or, if NWC declines, we’ll add it). Remember that an increase in NWC is a use of cash so that’s why we’re subtracting it. If NWC is negative, we’ll add NWC to our FCF as it’s a source of cash. Finally, we’ll subtract capital expenditures as well, which leaves us with unlevered FCF. For levered FCF, it’s the same process, but before multiplying by (1-t) we’ll take off interest expenses and add any interest income. At the final stage, when subtracting capital expenditures, we’ll also take off any mandatory debt repayments. Whenever you think about unlevered or levered FCF, think about who these cash flows belong to, which we’ll cover in the next question. While these formulas appear to be quite objective, in practice lots of arguments will be had about what non-cash items to add back (or not). 2. Who does unlevered and levered free cash flow really belong to? When thinking about any company, you can think about there being two distinct groups that have different claims on the company’s cashflow. On the one hand, you have the equity holders. These individuals are the “owners” of the company, and they have a residual claim on the company’s free cash flow (given that common equity is at the very bottom of the capital structure and is not contractually guaranteed anything). On the other hand, you have the debt holders. Debt holders aren’t “owners” of the company per se, but they do have a higher claim on the free cash flow coming into the company and, as a condition of giving the company money, have tied the company to following certain covenants (around leverage, interest coverage, the ability to further incur debt, etc.). When free cash flow comes in the door, debt holders need to be fed first before anything is passed along to equity holders. If they aren’t fed enough – meaning they aren’t given their cash interest or mandatory debt payments – that places the company into a “technical default” and they’ll be forced into filing bankruptcy (in the U.S., this would be either a Chapter 7 liquidation or a Chapter 11 reorganization), TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 3 So, it makes sense to think about what cash flows belong to the entire firm (both debt and equity holders) and what cash flows belong to just the equity holders. With unlevered free cash flow, you purposefully ignore the impact of debt because you want to capture the free cash flow available to all parties (both debt and equity holders). This makes unlevered free cash flow a capital structure neutral metric. This, in turn, allows you to compare the unlevered free cash flow values between two companies with ease (as the unlevered free cash flow is not being influenced by whether a company has financed itself through a different mix of debt and equity than another company). With levered free cash flow, you just want to show what is available to equity holders after dealing with debt holders. So, you take out interest expense and add interest income before multiplying by (1-t) as we need to account for that tax shield provided by interest expense. Further, we take off mandatory debt repayments at the end to reflect the cash flow that that needs to go toward mandatory principal balance reductions (e.g., term loan amortization). Thus, comparing levered free cash flows between two companies isn’t necessarily an apples-toapples comparison. Two companies could have the same unlevered free cash flow, but if one funded itself with equity, while the other took on debt, then the one that took on debt will have a lower levered free cash flow. 3. For tech companies, SBC is traditionally a major expense. Should it be added back to FCF calculations? First of all, we aren’t told whether we’re talking about unlevered or levered FCF. For levered free cash flow - which we’ll use in LBO models for determining debt paydown, for example – it entirely makes sense to add back SBC as it’s non-cash and will give a distorted view on how much leverage (debt) the target can sustain. When it comes to unlevered free cashflow, arguments can be made either way. However, in practice it’s rarely added back. Remember: Unlevered FCF, by being a value relevant to both debt and equity holders, strips out the effect of the capital structure (in other words, it’s capital structure neutral). So, if you’re excluding SBC (adding it back) then you are benefiting companies that happen to use stock comp. In reality, while SBC and cash compensation differ as discussed in the accounting questions, they are both operating expenses. Remember: The purposes behind calculating unlevered and levered free cash flow are different. With unlevered free cash flow, you’re often using it to compare companies to each other. By adding back SBC, you’d be benefiting those who make the decision to pay more with stock than cash. So, you arguably would not be getting an apples-to-apples comparison by adding SBC back. Note: Also, don’t get tripped up on terminology here. If you’re asked whether SBC should be excluded from unlevered FCF calculations, keep in mind that means whether or not you should add it back (as it’s already included in the calculation). TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 4 4. What’s one major issue we could run into when doing a DCF for companies in the TMT space? The obvious issue – that’s particularly prevalent within the tech space – is having limited FCF in the early years and an inability to make reasonable assumptions about when meaningful FCF will eventuate and how large it’ll end up being. Ultimately, when you’re projecting out a DCF for five years, and staring at negative or only modest FCF over that period, then your terminal value will end up being 90-100% of the total EV. When your terminal value is derived from the multiples method, the question then becomes: why go through the exercise of doing out a DCF for this anyway? Why not just look at a comp set, find a range of EBTIDA multiples, and apply that to the company’s LTM EBITDA or NTM EBITDA? Ultimately, for banking purposes, you’ll almost always be doing a DCF to come up with a valuation so you can look at it in conjunction with precedents and comps to get a better feel for the valuation range of the company. However, the important contextual thing to understand here is that while for an industrials company the DCF may be the centerpiece of valuation (the thing that your confident is giving you a true sense of the value of the company) for many tech deals the DCF will just be something done to have as another data point. Comps will probably be what’s emphasized in client meetings and what drives discussion around the appropriate value of the company. 5. After we calculate levered free cash flow and unlevered free cash flow, what are the discount rates we will be using? Since unlevered FCF belongs to both debt and equity holders, we’re going to use WACC (which provides a weighted average cost based on the current capital structure makeup of the company). For levered FCF, which has already dealt with debt holders and is the residual cash flow left for equity, we will be using cost of equity. WACC = Cost of Equity * (% Equity) + Cost of Debt * (% Debt) * (1-t) + Cost of Preferred * (% Preferred) Cost of Equity = Risk-Free Rate + (Market Risk Premium * Levered Beta) + Size Premium Within the WACC, for the Cost of Debt you can use the current blended yield of the company you’re looking at. The same holds true for the Cost of Preferreds (if the company has them). For the Cost of Equity, in practice the Risk-Free Rate will almost always just be the current yield on the 20-year treasury (or equivalent 20-year govie bond if the company is domiciled in a different country than the U.S.). The market risk premium is generally pulled from a guide like Duff & Phelps or Ibbotson’s. In practice, you can just pull it from FactSet, Bloomberg, or CapIQ. However, these guides are also where you’ll find the size premium if you’re dealing with a smaller firm (using a size premium is purely discretionary and is something you’ll be told to add by a senior in the group). TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 5 Finally, you’ll need to get the levered beta for the company. As you likely already know, you’ll just be taking a comparable set of companies, unlevering their betas, taking the mean or median, and then levering back up based on the capital structure of the company you’re looking at. Note: I’ve gone through all this quite quick since this is a relatively basic question (although, in practice, lots of arguments occur about what the appropriate WACC or COE is for a company as it heavily affects valuation). I just decided to cover this question so you have a quick reference as we can get into more interesting questions. 6. Let’s say we’ve unlevered the beta of five comparable companies. These unlevered betas range from 1.05 to 1.15. The company we’re looking at has a capital structure comprised of 20% debt with a tax rate of 25%. What’s the relevered beta? First, let’s quickly recap the unlevered and levered beta formulas. Unlevered Beta = Levered Beta / (1+((1-t)) * (Debt/Equity))) Levered Beta = Unlevered Beta * (1+((1-t)) * (Debt/Equity))) So, as you’ll do a million times in banking, we’ve unlevered the betas of five comparable companies. Practically, what this means is we’ve created a metric (unlevered beta) that shows how volatile the company is – relative to the market in general – in a capital structure neutral way. Generally, what you’ll do after is find the mean and median (often they’re very close to each other) of the unlevered betas you found. You’ll then use one of these in order to relever the beta for the company you’re looking at (you’ll use the median if there is a wide spread between the comparable company unlevered betas you found). Given that we weren’t told what each individual beta was in this question, we’ll just take the midpoint of 1.10. So, to relever our beta - based on the unlevered beta found above – we’ll simply calculate: 1.10 * (1 + (0.75*20%)) = 1.265. Note: The expectation will not be that you can calculate this all in your head. You’d just need to lay out what the calculation is. 7. What would a beta of zero mean? What about a beta of one? Often interviewees can run through the unlevered and levered beta formulas with ease, but when you ask them, “Wait a minute, what even is beta?” they look at you blankly. Remember that beta is just a number that indicates how volatile the equity price of a certain company is relative to the overall market. So, you can have separate betas calculated for a stock. For example, there could be a beta relative to the S&P (most common), one relative to a separate index (for example, the S&P’s Semiconductor Index, PHLX), etc. § § A negative beta is very uncommon but would indicate that an equity moves up when the broader index being compared to the equity moves down (and vice versa). A beta of zero would be something like cash. Whether the broader index being compared moves up or down is irrelevant; the price of something with a beta of zero would stay constant. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 6 § § § A beta between zero and one would correspond to an asset that moves with less volatility, but directionally with the overall market. So, for example, many utilities will have a beta between zero and one. They go up as the overall market goes up, but they tend to be less volatile (meaning they go up by less than the overall market). Further, when the market declines utilities tend to decline as well, but by less than the overall market does. A beta equal to one would indicate that the company being looked at mimics the directionality of the overall market and its price movements (meaning, it’ll go up by the same as the overall market and down by the same as the overall market on any given day). A beta greater than one means that a company has more volatility than the overall market, so on any given day there will probably be larger swings in the value of the equity relative to the broader index. But the directionality over time will be the same (e.g., if the market is up 10% for the year, you’d expect a stock with a beta of greater than one to be up by more than that). 8. Could a company ever have a beta of 100? No. If the beta of a company is 100 then a company’s volatility is 100x greater than the market the company is being compared to. Meaning the company would go to zero whenever a modest decline occurred in the broader market. 9. As the percent of debt that makes up the capital structure increases, what does that do to beta? Think for a moment about the capital structure of any company. At the very bottom you have equity, which has a claim on the residual cash flows of the company after having dealt with everything above it in the capital structure (e.g., revolvers, term loans, secured notes, unsecured notes, convertible bonds, etc.). Now, as we discussed above, beta is a number that illustrates how volatile equity is relative to the broader market. So, you’d expect that the more levered a company is (meaning the more debt it has) the more benefit equity holders will accrue during the good times and the more pain equity holders will endure during the bad times (as there will be limited or perhaps no cash flow left after meeting debt obligations during the bad times). So, for this reason, as the percent of debt that makes up the total capital structure increases, the higher the beta will end up being. Of course, you could just run the calculations quickly yourself to see that this is true. But in an interview you’ll be asked why this is the case, not just what happens when the percent of debt that makes up the capital structure increases. 10. When thinking about the WACC, is it true that debt always cheaper? This is another more conceptual question. Not only does debt provide a tax shield – which is why we multiply debt by (1-t) in the WACC equation – but debt also resides higher in the capital structure so has a higher priority and has the ability (through covenants) to dictate how much more debt can be placed by the company, how levered the company can get, etc. You may have read online that as the percent of debt increases to high levels, WACC begins to go up (as the cost of debt begins to increase significantly). Therefore, the minimal WACC would be some blend of equity and debt, but not an extreme of either. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 7 Theoretically this is true, but the reality is that no company can go and keep on issuing debt at ever higher coupon rates to fund itself. Within credit docs there will be verbiage surrounding “permitted indebtedness” that prevents how much further debt can be raised. So, there is a practical binding constraint on total debt a company can take on. Further, even if this were true that a company could keep on adding ever more debt, what would that do to the cost of equity? It’d keep getting pushed up, because of the amount of debt in front of it (which is growing ever riskier to current debt holders, because there’s so much of it). In my view, it’s practically untrue to say that at a certain point a company has so much debt that it becomes cheaper to equity finance. Think about it this way: if you were a buyside investor looking at an incredibly highly levered company and you had to buy either debt or equity, which would you choose? You’d still want to buy debt from them not equity given that debt will have seniority over equity in any restructuring that may occur in the future (meaning debt holders may get some recovery value, while equity will per se get less or none). 11. So why do companies ever issue equity if debt is invariably cheaper? What’s the point? First, there may be some practicalities that preclude raising more debt. If you have a term loan of $1B there will be language saying there can’t be more debt raised at this level, so you’d only be able to raise unsecured notes, which maybe the market has less appetite for in the size you’re looking for. Further, imagine you’re a company in the tech space. You’re growing rapidly, but you’re not profitable yet. Yes, theoretically, it’s cheaper to issue debt, but do you feel comfortable that you have the cash to meet the cash interest expenses that come along with it? Equity is more expensive – again, theoretically – but it also doesn’t come along with the cash outflows that debt does. Even if you issue dividends to common equity holders, you don’t need to keep doing that (although holders may not like it if you stop!) whereas with debt holders you need to make cash interest payments or else you’ll be in technical default. Note: Many startups will issue preferred stock or converts with non-cash interest to get debt-like instruments without having to issue more common stock and dilute themselves down during their heavy growth phase. 12. Practically speaking, what method is almost always used to determine the terminal value when doing a DCF? There are two ways in which you can think about valuing the terminal value in a DCF: using an exit multiple or using a perpetuity growth rate. Either way what you’re doing is getting a valuation that represents the value of the company from the final year in which you forecast FCF out into infinity (which will then be discounted back to get a PV, which will then be added to the discounted FCF over your forecast period). So how does this work in practice? Should you use exit multiples or assume some perpetuity growth rate? In practice, you’ll almost always use an exit multiple applied against the final year of EBITDA that you forecast (unless there are limited comps so finding an exit multiple is hard). TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 8 However, what you’ll do is also find out what the implied perpetuity growth rate is based off of the last year of forecasted FCF, the WACC, and the terminal value you found via the multiples method. This implied perpetuity growth rate – covered in the next section – is designed as a form of check. If you find out that you have an implied growth rate of 6% or more that’d be a very aggressive assumption. Ideally, you’d like to see things in the 2-4% range. If you are higher than 4%, you should consider whether or not you’re applying too high of an exit multiple to your final year of forecasted EBITDA. Note: Using the exit multiple method, philosophically, is essentially saying, “We’re going to forecast the unlevered FCF over the first five years, and then pretend at the end of five years we sell the company at the exit multiple. So, if we did that, whatever the PV of these cashflows are is our enterprise value today.” 13. Let’s say a company has FCF of $500 in the last year the DCF is done, a WACC of 10%, and a terminal value (found via the multiples method) of $7,000. What’s the implied perpetuity growth rate? The formula for the implied perpetuity growth rate is: Implied Growth = (Terminal Value Before Being Discounted * WACC – FCFn) / (Terminal Value Before Being Discounted + FCFn), where n is the last year that you’ve forecast for. So, in this example we’d have (7,000 * 10% - 500) / (7,000 + 500), which gives us 2.66%. Note: There’s no need to give the exact percentage in an interview, of course. Sometimes you’ll be given numbers that work out, other times you’ll have to settle for just the fraction 200/7500 or 2/75. Note: In practice the formula used is a bit more complicated, but don’t worry about that for interview purposes. 14. When would the implied perpetuity growth rate equal zero? This would happen when the TV found via the exit multiple method, multiplied by the WACC, is the same number as the FCF of the last year forecast. Following up with the question above this one, FCF of $700 in the final year forecast would make the numerator 0 and thus give an implied perpetuity growth rate of zero. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 9 15. What kind of sensitivity tables are common to use with a DCF? Below are the most common sensitivity tables that will almost always be included: § § § § Enterprise Value (at various WACCs and Exit Multiples) Implied Equity Value (at various WACCs and Exit Multiples) Implied Perpetuity Growth Rate (at various WACCs and Exit Multiples) PV of Terminal Value as a Percent of EV (at various WACCs and Exit Multiples) 16. What would have the larger positive impact on the EV found via a DCF, reducing WACC by 1% or increasing the exit multiple by 1.0x? Increasing the multiple by 1x will have a much greater impact and it’s virtually impossible for it have a smaller impact than reducing the WACC (unless the TV somehow made up a very small percent of the total EV). You can verify this on the sensitivity tables above. If we have an EV of $3,794 and raise the multiple by 1.0x we’ll have an EV of $4,105. Whereas, if we keep the same multiple but decrease the WACC by 1% we’ll get an EV of $3,925. 17. What would have the larger positive impact on the EV found via a DCF, increasing revenue growth by 1% or decreasing WACC by 1%? Generally speaking, decreasing the WACC will have a larger impact here. While increasing revenue has a significantly positive impact over the projected period, at the end of year five (or whenever the projected period ends) you’ll then just be multiplying EBITDA by an exit multiple. Whereas with WACC you’ll be discounting each of the projected years and the entire terminal value by a lower percent, thus increasing the value of the EV. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 10 18. Let’s say we have a WACC of 10% and have projected that we’ll have $500 of unlevered FCF over the next five years. Can you run down how you’d determine what the PV of these cashflows are? No need to give me the exact numbers, just layout how you’d arrive at them. What this question is getting at is whether or not you know what the mid-year convention is (which is almost always what is used, as it better reflects that we get cashflows coming in through the year not at the end) and what the discount factor that should be applied against the $500 in annual cashflows should be each year. A picture perhaps provides for a better explanation: So, the discount period will use a simple mid-year convention: 0.5 for year one and then increasing by 1 for each year thereafter. The discount factor will be: 1 / (1+WACC)^n, where n is the discount period we’re referring to. So, for example, in year two the discount factor will be (1 / (1.1^1.5)) or 0.867. We then multiply that number by the cashflows we project to have that year ($500) to get the PV of those cashflows ($433.39). Again, you won’t be expected to work this all out at all. Rather, your interviewer just wants to see that you can lay out that you begin with the cashflows, lay out the discount period, find the discount factor, and then find the PV by multiplying the cashflows by the discount factor. 19. What about when you create the terminal value using the multiples method, what’s the discount period then? After you’ve forecast FCF for five years, using the mid-year convention for your discount factor, you need to come up with an exit multiple to find your terminal value. Here we’re saying we get this at the end of five years, so we no longer are trying to smooth out cashflows, which was the rationale behind using the mid-year convention. So, we’ll add 0.5 to our year 5 discount period, which gives us 5. Likewise, if we projected for ten years, we’d use a discount period of 10 (as our year 10 discount period would’ve been 9.5, so we’d just add 0.5). TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 11 20. After we find out EV via a DCF, how do we then navigate to our implied equity value and share price? Here we’re just going to be working backwards. Taking off debt, preferred stock, and noncontrolling interests (and anything else relevant, like capital leases), and adding cash (and anything else relevant). 21. What if we’re looking at company with a year end of Dec 31, but we’re starting our valuation at the end of Q2 and want to use the mid-year convention? What are our discount periods then? This is obviously very common. When you’re trying to value a target, you can’t just say, “Let’s forget about everything before their next fiscal year begins and then start our valuation from there.” The solution is to use “stub periods” where the stub refers to the time between when you start your valuation and when the next fiscal year begins. All you need to remember for stub periods are two things when using the mid-year convention: § § You take the stub period and divide it by two. You take every future year discount period and subtract 0.5. So, if we’re beginning our analysis after Q2 ends, then we have Q3 and Q4 left before the next fiscal period begins. Therefore, the discount periods without using the mid-year convention would be: Stub: 0.5, Year 1: 1.5, Year 2: 2.5, Year 3: 3.5, etc. Using the mid-year convention, the discount periods would be: Stub: 0.25, Year 1: 1, Year 2: 2, and Year 3: 3, etc. If you’re ever asked a question about this, it’s always a good idea to write out the regular discount period and then show it with the midyear convention so you make sure you don’t make any mistakes. Remember: To get the mid-year convention just divide the sub discount period by two and then for every future year take 0.5 off of the original discount period (that isn’t using the mid-year convention). TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 12 22. How do you handle convertible bonds when calculating WACC? For converts, if they’re in-the-money (ITM) then you assume they convert and add to equity value. If they aren’t ITM then you count them as debt and their underlying yield will need to be considered when determining the overall cost of debt for the company. 23. What tax rate should you use in a DCF? How can lowering tax impact a DCF? You should use a normalized effective tax rate and hold it through the entire time (e.g., 25% or 20%). Being asked about the effect of lowering the tax rate is a really interesting question to ask, because there are countervailing pressures. Reducing the effective tax rate will (obviously) increase the amount of unlevered FCF generated. However, it will also cause the after-tax cost of debt to increase, which puts upward pressure on the WACC, which reduces the PV of FCF. Further, think back to our unlevered beta formula, we’re multiplying D/E by (1-t) so as we reduce the tax rate, levered beta will increase, which increases our cost of equity and, in turn, our WACC. You’d have to flow through changes to the effective tax rate to see how these changes ultimately effect EV. However, the important thing to recognize is that while FCF increases from a decline in the effective tax rate, the discount rate (WACC) will increase leading to the PV of those enhanced cashflows being worth less than they otherwise would be. 24. Rank the following by how much they’d increase the value of unlevered FCF: a $100 increase in revenues, a $100 decrease in SG&A, or a $100 decrease in capex? Think about where each of these line items fall within an unlevered FCF calculation. Revenues and general expenses are pre-tax, while capex is post-tax. So, right off the bat, we know the capex must provide the biggest increase to FCF as it isn’t reduced by taxation. It simply increases unlevered FCF in a year by $100. After that, we would have the cutting of SG&A. These are pre-tax expenses, so would increase FCF by $80 (assuming a 20% tax rate). Finally, an increase of revenue would have the smallest impact of the three. Not only would it be impacted by taxes, but an increase in revenue would generate COGS. So, if COGS were 30% ($30) of revenue that’d leave us with a $70 gain pre-tax, which would lead to a FCF increase of $56 assuming a 20% tax rate. Note: If there was somehow a 100% gross margin (no COGS) then a revenue increase of $100 and a SG&A decrease of $100 would have an equal impact on unlevered FCF. Note: You can make an argument that an increase of revenue would have additional benefits that make it most valuable in an overall EV calculation, because we would have baked in an annual revenue growth assumption in our model. So, this additional $100, if incurred in year one, would carry forward, grow, and compound in future years. Whereas the reduction in capex and SG&A would have been one-time benefits (as they are usually modeled as a percent of revenue). But the question notes unlevered FCF, not EV. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 13 25. How would raising $100 of debt (that pays a 6% coupon) in year two affect the DCF valuation of a company? For the unlevered free cashflow calculations that underpin a DCF, there will be no impact from raising debt (as unlevered FCF is capital structure neutral). With that being said, what you discount the unlevered FCFs by during the forecast period (along with the terminal value) would change as the capital structure will now be more debt heavy. Assuming that the debt raised is at a lower cost than the cost of equity, this additional debt will lower the WACC, and thus increase the PV of the FCFs after year two and the terminal value. Thus, increasing the ultimate EV found for the company. 26. How would a company buying $100 of equipment in year three impact the DCF valuation of a company? Remember that when figuring out unlevered FCF, capex (along with changes in NWC and D&A) come after taxes. So, an increase of $100 in capex in year three would lead to a reduction of $100 in unlevered FCF for that year. However, also remember that this won’t equate to a reduction of $100 in our EV found via a DCF. Given that this $100 reduction in cashflow is in year three, we need to discount this back to the present by the WACC. Assuming mid-year convention, it’d be ($100 / ((1 + WACC)^2.5)). If WACC were 10%, the amount that the EV of our DCF would decrease would be $78.79. Note: If you’re asked this type of question about capex, changes in working capital, or depreciation or amortization the answer process will be the same (but, of course, if it’s a decline in NWC that’ll be an increase to cash flow not a decrease). 27. In a DCF model, how do you think about projecting line items within unlevered FCF? Generally, you’ll assume some revenue growth rate in line with the history or perhaps bumped up (or down!) due to your assumptions about the future performance of the company. Then COGS, SG&A, D&A, and capex will all be held at a percent of sales through the forecast period. So, for example, if over the past three years COGS had been 27%, 28%, and 26% of revenue you might say that moving forward, for each year forecast, we’re going to say that COGS are just 27% of whatever revenue is. The final thing we’ll need to consider is NWC. Often NWC will be broken out more granularly and not held just as a percent of sales (although it could be if you need to go quick). Here are some of the major NWC contributors and how they’re determined: § § § A/R – (Days Sales Outstanding / 365) * Revenue (where DSO will be a static number held through the forecast period based on what it has been historically on average). Inventory – (Days Inventory Held / 365) * Revenue (where DIH will be a static number held through the forecast period based on what it has been historically on average). Other Current Assets – Unless told otherwise you’ll make all other current assets just a percent of sales (using whatever percent they’ve been in the past, on average, for the forecast period) TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 14 § § Accounts Payable – (Days Payable Outstanding / 365) * Revenue (where DPO will be a static number held through the forecast period based on what it has been historically on average). Other Current Liabilities – Unless told otherwise you’ll make all other current liabilities just a percent of sales (using whatever percent they’ve ben in the past, on average, over the forecast period). TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 15 Enterprise and Equity Value Questions 1. Let’s start off with the basics, what do enterprise value and equity value really represent? Just as WACC is a discount rate applicable to everyone who has a direct economic interest in a company – whether they’re a debt or equity holder – likewise enterprise value represents the total value of a company to all holders. Perhaps a way to reinforce this concept would be that if a company were to file bankruptcy, you’d determine the enterprise value in order to figure out the value of the company. You’d then begin paying off each tranche of debt by order of seniority and then see what’s left for equity holders (usually there’s nothing left in a bankruptcy for equity holders, but in some cases, like Hertz, you do have some left!). Equity value, on the other hand, is just the value that belongs to those who hold the common stock of the company. This is the value that, divided by total shares outstanding, gives you the stock price. 2. Why does using Equity Value / EBITDA not make any sense? It’s useful whenever you’re thinking about multiples to ask yourself, “Are both of these things taking into account interest expense and interest income?”. If the numerator and denominator differ in whether or not they consider these things, then the multiple isn’t going to tell us anything meaningful. In this example, equity value includes interest expense and income (meaning, we’ve already dealt with debt by the time we get to equity value, and thus equity value is the residual value available to shareholders). However, EBITDA is, as the name implies, earnings before interest. So, EBITDA is a value that is attributable to both debt and equity owners. So, Equity Value / EBITDA is somewhat nonsensical because we’re saying, “Here’s all the value attributable to shareholders, and we’re going to divide that by the value belonging to both debt and equity holders.” It’s impossible to really infer anything from that. 3. What’s the formula for enterprise value? Depending on the company you’re looking at, EV formulas can get a bit involved and in an interview it’s always better to say what you know well, as opposed to giving every possible line item that could be included (if you can’t give a plausible explanation as to why). At its most basic level you should think about EV using three rules of thumb: § § § Things that are cash-like should be subtracted (meaning things you could reliably and predictably sell for a relatively known quantity of cash). Things that are debt-like should be added. Things that do not affect the denominator of an equation (e.g., EBITDA when calculating EV / EBITDA), such as equity investments should be subtracted (remember these are broken out below ParentCo net income). TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 16 If you’re ever asked whether something more complicated should be added or subtracted, begin your explanation with those three points. Then, even if your interviewer disagrees with your actual answer, they’ll know you’re thinking about EV through the right mental model. The most standard EV formula is: EV = Equity Value + Debt – Cash – Cash Equivalents + Preferred Equity + Non-Controlling Interest A slightly more involved formula, would be: EV = Equity Value + Debt – Cash – Cash Equivalents – Shore-Term Investments – NOLs – Equity Investments + Capital Leases + Preferred Equity + Unfunded Pension Obligations + Non-Controlling Interests In future questions, we’ll get a bit more in-depth. Keep in mind, however, that often DCFs will just use the more standard formula above. 4. So, you’re telling me that EV represents the full value of the company and what an acquirer would roughly have to pay for it. But when they acquire a company they’ll get the cash, right? So why take it off? Let’s do a little proof by contradiction here. Let’s imagine we’re trying to come up with the EV of a company. They have an equity value of $1,000, $500 in debt, and $100 in cash. We’re stipulating that the formula for EV, given this balance sheet, should be: EV = Equity Value + Debt – Cash. The debt part should make sense given that in order to acquire the company we have to assume the debt (or, more practically, pay off the debt given that the debt will likely have Change of Control provisions). But what about the cash? We’re saying to take it off. Let’s imagine two scenarios. § § First, let’s imagine that the equation for EV added cash instead of subtracting it. Second, let’s imagine that the company, just prior to our acquisition, paid down their debt with their cash. If we work out the math, in the first scenario the EV would be $1,000 + $500 + $100 or $1,600. In the second scenario the EV would be, $1,000 + 400 or $1,400. Well, how could this make sense? We’re adding cash in this formula, which seems to make sense since cash is an asset and should be adding to the cost of acquiring the company, but if the company we’re acquiring just happened to pay off their debt with cash just before the acquisition (which also makes intuitive sense) that leads to a different result. The reality is we take off cash and cash-like assets – that can be reliably and predictably disposed for a relatively known cash amount – because these could be used theoretically to “finance” the transaction by the acquirer. Put another way, the amount the company needs to put up for the company is reduced by the cash balance of the TargetCo. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 17 5. What about preferred equity and non-controlling interest? Why are those added? Preferred equity is added because it’s debt-like (both in terms of its seniority in the capital structure, being above common equity, and due to the potential fixed dividends associated with it). Non-controlling interest touches on the third rule of thumb I listed in a prior question. When you own over 50% of a company, but less than 100% you consolidate the financials. So, EBITDA (the denominator of the EV/EBITDA multiple) will reflect 100% ownership. In order to keep things apples-to-apples you’ll need to add back the non-controlling interest from shareholders’ equity in order for EV to reflect 100% ownership. If you didn’t do this, then the multiple would be lower than it otherwise would be (as the EV would be smaller from not including Non-Controlling Interest). 6. What about other things that we add back or subtract from EV, can you walk me through a quick rationale for those? As was mentioned in a prior question, a slightly more involved formula for EV would be: EV = Equity Value + Debt – Cash – Cash Equivalents – Shore-Term Investments – NOLs – Equity Investments + Capital Leases + Preferred Equity + Unfunded Pension Obligations + Non-Controlling Interests So far, we’ve already covered a few of these – like equity value, debt, cash, preferred equity, and non-controlling interest – so let’s cover the rest. Cash equivalents – which are very liquid and have a predictable cash conversion value – are always subtracted as they are essentially equivalent to cash (thus the name). Short-term investments can be looked at closer to see whether or not they are liquid (can be sold off like cash equivalents) and have a predictable value like some Trading Securities will. For some forms of short-term investments this may not be applicable. If there’s any doubt, you don’t take these off. For NOLs, it’s obvious that if you’re including them, you’d be subtracting them given that they’ll help produce cash tax savings in the future (and can be carried forward by the acquirer). These cash tax savings are captured by DTAs, which should be subtracted from equity value when doing an EV calculation. The rationale being that equity value implicitly accounts for the value of these DTAs, but with our EV we’re trying to find the true value of the firm and the denominator of our most common multiple (EV/EBITDA) won’t be capturing the DTA value (thus if we don’t subtract them, we’ll have an artificially high EV and thus an artificially high multiple). Further, when comparing EV/EBITDA multiples across comparable companies, all else being equal those with high NOL balances would have artificially high multiples stemming from the NOLs baked into their equity values, which doesn’t allow you to really compare companies in an apples-to-apples way. Equity investments will also be subtracted. If you think back to the accounting questions – where I covered a number of equity investment scenarios – you’ll remember that equity investments (when you own less than 50% of another company) result in placing a line item below net income of the ParentCo, but not in combining the financials (so there’s no increase in revenue or EBITDA TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 18 from the equity investments). So, following the third rule of thumb I listed in a prior question, you need to deduct equity investments or else you’d be counting equity investments (which will be captured within equity value), without there being a counterbalancing impact on EBITDA (so your EV/EBITDA will be artificially high). Finally, we add back capital leases and unfunded pension obligations. Capital leases are considered debt, because they involve the ownership of an asset today in all but name. Unfunded pension obligations, if they are of sufficient size, should be included because they will require financing (e.g., more debt) to be raised in the future in order to properly fund them (it just so happens that the financing hasn’t been raised as of yet, which is why they are underfunded!). Depending on the company you’re looking at, there can be additional things to add or subtract. For example, if you had a large unfunded tort claim or other legal liabilities that are known, but have not yet been paid, these would need to be added (as they will need to be funded in the future). Remember: Unfunded pension liabilities or other legal liabilities are going to be a cash drain in the future, so the cost of purchasing the company increases as we’re going to be assuming those liabilities (and need to fund them being distinguished at some point). 7. Let’s say that you raise $100 in debt and use the cash raised ($100) to buy a piece of equipment. How does this impact EV? For many, this is a bit of a tricky question. Before you think about what’s going up and down in the EV equation, take a step back and think about it logically. If a company raises $100 in debt to buy a piece of equipment worth $100, how much should the cost to hypothetically acquire the company (EV) go up? The answer is probably $100, right? It wouldn’t make sense if the company became less expensive to purchase, right? Let’s go through our EV equation. We raise $100 in debt, which means we have debt going up by $100 and cash going up by $100. This means that our EV doesn’t actually change from the debt raise itself as the debt is offset by the cash coming in the door. Think back to when I explained why cash decreases the value of EV; it’s because cash preacquisition could just be used to lower the debt. So, carrying forward that logic when a company raises debt, but just keeps it as cash, that shouldn’t affect the EV. However, once the company has the $100 in cash, in this question it does put it to use by buying a piece of equipment. So, cash goes down by $100, which means that out EV goes up by $100 (as remember we’re subtracting cash, so when cash goes down the EV goes up). So, the answer is that the EV is up by $100. 8. Let’s say the company issues $100 in new equity (or new debt) what happens to EV? Hopefully you know the answer immediately after having gone through the last question. When we raise new equity the equity value of the company will go up by $100 (which raises the EV by $100), but cash will also go up by $100 (which lowers the EV by $100) thus there’s no change. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 19 The same is true with raising $100 in debt. Debt goes up by $100 (which raises the EV by $100), but cash does as well (which lowers the EV by $100). 9. EV multiples don’t always involve EBITDA. In particular, for tech companies we may use revenue or MAU. Would you use equity value or enterprise value when creating multiples for revenue or MAU? When it comes to revenue, you’d use enterprise value given that revenue belongs to both shareholders and debt holders (as the revenue will be used, in part, to pay any cash interest or mandatory debt repayments). When it comes to MAUs, or any more abstract metric, you’d use enterprise value as well. The rationale being that MAUs don’t just produce economic gains for shareholders. Rather, they drive overall revenue, which flows down to both debt and equity holders. 10. Let’s say you have a company with an EV/Revenue of 5x and an EV/EBITDA of 10x. What’s the EBITDA margin? So, your EBITDA margin will just be the percent found when you divide EBITDA by Revenue. You can approach this two different ways. First, you could just make up some EV, say $100, and then we can infer that EV/Revenue would be $100/$20 based on the 5x multiple and EV/EBITDA would be $100/$10 based on the 10x multiple. Therefore, EBITDA / Revenue would just be $10/$20 or 50%. Or you can set up these equations and do the math. EV/Revenue transforms into 5/1 and EV/EBITDA is inverted to EBITDA/EV, which gives you 1/10. Thus, (5/1) * (1/10) = 5/10 = 50%. 11. Let’s say a company has 8,000 shares currently trading at $20. There are 100 exercisable call options at a price of $10, 50 restricted stock units (RSUs), 50 performance shares at $30, and 100 converts at a price of $10 with a par value of $100. What’s the fully diluted share count and equity value? So before counting dilution we have 8,000 shares and an equity value of $160,000. In this question we’re dealing with every type of dilutive security you could be asked about in an interview. So, let’s work through each one sequentially. First, we have the call options. We have 100 of them at a price of $10, which is obviously in the money given equity is currently trading at $20. So, when these options are exercised, the company will receive $1,000. Assuming that the company uses these proceeds to buy-back shares at the current trading price of $20, that means that 50 shares can be bought back (leaving 50 shares leftover). So, from these call options we have 50 shares of dilution. Moving on to the RSUs, remember that these are just shares that employees are given, but that are locked up for a given period of time to incentive long-term performance and disincentive making short-term decisions to solely boost the current share price. So, assuming this is an acquisition scenario, these would be added so you have another 50 shares of dilution. Performance shares are those given to employees if the stock hits a certain price in the future. If they’re ITM then they count toward dilution, but if they’re OTM they are just ignored (not treated TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 20 as debt as is the case for converts that are OTM). So, because these shares are OTM, they have no impact whatsoever. Finally, we have 100 of converts at a price of $10 and a par value of $100. To find the number of shares created per convert, take the par value ($100) and divide it by the price ($10). This gives us 10 shares created per convertible bond (if the converts are ITM). Since there are 100 of these convertible bonds that are ITM, this will lead to 1,000 new shares being created (100 converts * 10 shares created per convert). So, in total we have 1,000 new shares from the converts, 0 from the performance shares, 50 from the RSUs, and 50 net new shares from the options (100 created, 50 bought back) leaving us with 1,100 new shares in total. Equity value will now be $160,000+(1,100*$20) = $182,000. 12. Let’s say we (ParentCo) acquired 80% of a company (TargetCo) for $400. TargetCo had $300 of revenue with an EBITDA margin of 30%, $100 in debt, $20 in cash, and $30 in short-term investments. What was the EBITDA multiple for the deal? So, if we’re acquiring 80% of TargetCo for $400, then the full equity value will be $500. Likewise, if TargetCo has $300 in revenue with an 30% EBITDA margin, then EBITDA will be $90. The EV will be: EV = $500 + $100 - $20 -$30 = $550. The EBITDA, as we found above, will be $90. Therefore, the multiple for the deal will be $550/$90 or 6.1x. As always for tricker mental math there will not be the expectation that you’ll get the exact multiple, just that you show the result as being $550/$90. You can say that the multiple will be slightly over 6x as you know 90*6 is 540, which is a touch below the EV found of $550. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 21 Merger Model Questions Note: Keep in mind that I’m going to go over just the most important and / or difficult questions that could be asked on merger models in an interview – you still need to know the basic questions! 1. Broadly speaking, what kind of acquisition rationales exist in the TMT space? I think you can safely break down the rationale for almost any acquisition in the TMT space into the following three: Acqui-hire. An acqui-hire is when a large company – normally within the internet or software subsector of tech – acquires a company purely to “acquire” the engineers that work there based off of the technical expertise they have gained through building their company. You’ll often see acqui-hire transactions for companies in emerging technical areas. So, over the last few years, you’ve seen this in the AI and ML space. The important point here is that companies that do an acqui-hire transaction aren’t doing so because they want the underlying technology or product that’s been created (or at least that’s not the overriding consideration). Instead, they want the people and will structure the compensation such that key individuals at the company are retained at the acquirer for a set number of years (normally 2-5) to work on the priorities of the acquirer. Emerging tech. Sometimes a large incumbent will just buy out a smaller company if they’ve developed something – either physically or digitally – that the company believes that they need. The underlying rationale here is that if the company thinks they can buy a company for less than it would cost to build out the thing internally, then it’s entirely logical. Further, this precludes another competitor to the incumbent from doing the same thing thus perhaps blocking the ability of the original company to even buy what the smaller company is making. Accretive. Finally, you have the classic rationale of the acquisition being accretive to earnings. In the old days when we said accretive it’d mean accretive day one. Nowadays most acquirers in the TMT space – in particular, in tech and media – take a longer view of something being accretive over a five- or ten-year time horizon (e.g., the Instagram acquisition by Facebook / Meta). 2. When we say that a deal is accretive, what does that mean mechanically? It means that the pro-forma EPS – derived from the pro-forma income statement divided by the new share count – is greater than the buyer’s initial EPS. So, for example, if the buyer’s initial EPS was $8 and the pro-forma $10, then it would be accretive by $2 a share (or 25%). 3. If a company with a 10x P/E ratio acquires another one with an 8x P/E ratio, will that deal be accretive or dilutive? Assuming an all-stock transaction, it’d be accretive as at 8x you’re getting more earnings for the price than at 10x. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 22 When you invert the P/E ratio, you get the earnings yield representing the amount of earnings you get for every dollar invested (e.g., a P/E of 10x gives you a 10% earnings yield, which means you get $0.10 of earnings for every dollar invested). In an all-stock transaction, the compensation stems from the issuance of new shares. So, you can think about it as the acquirer giving up $0.10 of earnings per dollar invested to get $0.125 of earnings per dollar invested in return. However, if the consideration in an acquisition is a mix of cash, debt, and stock (or anything outside of just being a pure stock consideration) then you’d need to work out the amount being spent on these other components before you can say definitively that the transaction is accretive. 4. Let’s say that a company (ParentCo) has a P/E ratio of 5x and wants to acquire a company (TargetCo) that has a P/E ratio of 8x. ParentCo can raise debt at 5%, currently earns 2.5% on cash, and it has a 20% tax rate. If ParentCo acquires TargetCo using 50% stock, 25% debt, and 25% cash, will this deal be accretive or dilutive initially? First, let’s go over some definitions: § § § The “cost of cash” for the acquirer is equal to the foregone interest that the cash could earn multiplied by (1-t). Of course, we need to multiple forgone interest income by (1-t), because interest income will be taxed. The “cost of debt” for the acquirer is equal to the interest rate on debt multiplied by (1-t) as debt gives us a tax shield (meaning: a tax benefit). The “cost of stock” is equal to the inverse of P/E (e.g., how much earnings you get per dollar invested, as we’ve already discussed). So, if this were an all-stock deal what would this deal be? Given that ParentCo would be acquiring more expensive earnings than its own, it would be dilutive. However, acquiring a company with stock is “expensive” relative to using cash and debt, so maybe we’ll get a different result if we run through the math. § § § The cost of debt will be 0.05*(1-0.20) or 4%. o 25% of the financing structure will be debt. The cost of cash will be 0.025*(1-0.20) or 2%. o 25% of the financing structure will be cash. The cost of equity will be 1/5 or 20%. o 50% of the financing structure will be equity. So, the weighted average cost of financing this transaction will be: (50%*20%) + (25%*4%) + (25%*2%) = 11.5% So, the cost of financing is 11.5%. What are we getting in return? A business that has a P/E ratio of 8x, which gives us an earnings yield (E/P) of 12.5%. So, the deal is now accretive! Whereas if it were a pure stock deal it would have been heavily dilutive. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 23 5. Let’s say that ParentCo has a net income of $200, a share price of $6, and 10 shares outstanding. TargetCo has a net income of $200 as well, but a share price of $5 with 8 shares outstanding. If ParentCo buys TargetCo in an all-stock transaction paying a 20% premium to the current trading price, what’s the level of accretion or dilution? First, we’ll need to calculate the EPS of the buyer as that will need to be compared to the proforma EPS that we find to determine the level of accretion or dilution. So, the EPS of the buyer will just be $200/10 or $20. After that, we’ll find the purchase price of TargetCo. We know the market cap currently is $5 * 8 or $40. However, TargetCo is being bought at a 20% premium in order to try to secure TargetCo shareholder approval, which will be ($40 *( 1 + 20%)) = $48. Now, since ParentCo is financing this transaction via stock it’ll need to issue $48/$6 or eight shares, where $6 is the share price of ParentCo and $48 is the purchase price of TargetCo. Now to find pro-forma EPS we need to take the combined net income ($400) and divide it by the pro-forma share count (10 shares outstanding of ParentCo, plus the eight newly created, so 18). This will give us pro-forma EPS of $400/18 or $22.22, which is slightly accretive (11.11%) to ParentCo’s original EPS found in the first step ($20). 6. Let’s say that ParentCo has EBITDA of $300 and TargetCo has EBITDA of $100. When ParentCo acquired TargetCo, there are $100 in revenue synergies and $50 in cost synergies. What’s pro forma EBITDA? Assume this is a tech acquisition and gross margins are very high (80%). First, let’s start off by just adding the two EBITDAs together to get $400. Then we’ll just add cost synergies to get $450 (as we can think of cost synergies as just being a reduction in SG&A, thus being an addition to EBITDA). For revenue synergies, you can think about them as coming is roughly two forms. Those stemming from pricing power (e.g., being able to raise pricing while keeping COGS the same) or those stemming from increasing the number of goods or services sold (which will result in more revenue, but also more COGS). If we assume that the revenue synergies stem from enhanced pricing power, then we’d add $100 in revenue synergies directly to EBITDA giving us $550 in pro-forma EBITDA overall ($400+50+$100). If we assume that revenue synergies will come from selling more goods and services, incurring COGS for each thing sold, then we need to strip out COGS (which we’re saying here are 20% of revenue). So, this would lead to pro-forma EBITDA of $530 ($400+$50+$80). 7. If a company has significant cash on the balance sheet, why might it pay in stock (or stock and debt) given the low cost of cash? What I would say is that if a deal is accretive when funding with stock (or stock and debt) then, sure, it would per se cheaper if you used cash. But why bother using your cash balance? TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 24 This is particularly true in the credit markets of 2021 / 2022 where spreads are at all time tights and liquidity is abundant. Further, given where equity markets are – in particular, in the TMT space – you might as well use your incredibly high equity price to fund the transaction and leave your cash balance for a rainy day, to expand out capex as needed without having to go raise ad hoc debt or equity, in case the pandemic causes future disruptions (or a recession) and credit markets seize again and there’s a liquidity crunch, etc. The reality is that almost all companies – even those impacted severely by the pandemic – have taken the opportunity over the year or two to access capital markets and raise cash (often for no specific use) because i) for most companies it’s never been cheaper and ii) the pandemic illustrated that maintaining cash on the books is not per se a bad thing. One more finesse point - that is relevant for companies that have robust capital structures, like in the telecom space – is that there is almost always a level of restricted cash the company must keep on the books. So, just because the company has $20M in cash doesn’t mean it can spend all of it necessarily. 8. Let’s say that we’ve put together a merger model and we want to maximize the amount of debt we can use in the transaction. How would we think about doing that? When an acquirer is looking to buy a company, they don’t always have the luxury of determining if they want to pay exclusively in cash, debt, or equity. For most, unless you’re Apple with their ungodly cash pile, they’ll need to use some kind of mix of cash, debt, and equity (all of which will have binding constraints). First, you’ll need to look at the existing credit docs of the acquirer and see how much debt capacity the credit docs permit. For example, can the acquirer raise more secured debt? If so, what’s the maximum amount? The binding constraint for incurring additional debt will be “permitted indebtedness” language in existing credit docs and the pro-forma leverage ratio, inclusive of the idealized debt being placed, not breaching existing covenants. What you’ll need to do is calculate what the pro-forma credit metrics will be under various scenarios. In this cov-lite credit environment, what you’ll be most focused on is leverage (Debt/EBITDA) through the capital structure. So, you’ll look at hypothetical scenarios where you take out the TargetCo’s debt and place new debt and then see how that effects secured leverage (which would encompass debt from the revolver and term loans), senior debt (which encompasses debt from the secured part of the capital structure and from notes issued), and then overall leverage (which will encompass secured, senior, and subordinated debt – or, in other words, all the debt of the company). You’ll then look at comparable companies to the hypothetical pro-forma company and see whether the credit metrics derived are roughly analogous to what these comparables have. You’ll also apply reasonable interest – based off of comparable debt that’s been recently issued – to determine coverage (EBITDA / interest) ratios to ensure they comply with any existing credit docs and are in line with what is contained in the credit docs of comparable pieces of debt to those that you would be issuing to fund the transaction. The point is that determining the optimal level of debt is not really an academic exercise with an objective answer. It’s based off of a study of what existing credit docs will allow you to do, what TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 25 type and level of debt comparable companies have raised, and whether or not credit markets right now would be receptive to the type and level of debt you’d be trying to raise for the transaction. 9. Let’s say we (ParentCo) buy a company (TargetCo) that has a P/E multiple of 20x. If we want to use all debt, what must the interest rate be on the debt to make the deal accretive? So, we know the earnings yield of the company we’re buying will be the inverse of the P/E ratio, so 5%. Therefore, our after-tax cost of debt must be below 6.25% to make the deal accretive. If we assume a 20% tax rate, then our equation would be (5% / (1-20%)) or 6.25%. So, practically speaking, if we could raise a term loan to fund this acquisition then the deal would likely be accretive (as in today’s credit market, even second lien term loans for a healthy company will come in less than 6.25%). If we’re trying to fund this acquisition with unsecured notes (unsecured bonds) then it gets a bit more ambiguous. The deal would probably be either just slightly accretive or a bit dilutive. 10. What type of sensitivity tables will you often find in a merger model? § § § § Debt / EBITDA o Find the leverage ratio based on the % of stock used in the acquisition vs. amount of debt. EBITDA / Interest Expense o Find the coverage ratio based on the % of stock used in the acquisition vs. the amount of debt. Accretion / Dilution Breakeven o Estimated dollar amount of annual synergies needed vs. the offer price for the deal to breakeven (not be accretive or dilutive). Accretion / Dilution Percent o Find the percent accretive or dilutive the deal is based on the % of stock used in the transaction vs. offer price paid. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 26 11. What is goodwill? What should it take into account? For a stock transaction, goodwill operates as a plug to account for the amount you’re paying for the company in excess of the net identifiable assets (with some adjustments). Goodwill = Equity Purchase Price – Shareholders’ Equity + Target’s Existing Goodwill – Tangible and Intangible Asset Write-Ups – Target’s Existing DTL + Write-Down of Target’s Existing DTA + New DTL From Transaction + Intercompany A/R – Intercompany A/P Let’s walk through this. When thinking about what makes pro-forma goodwill go up or down remember that goodwill will be an asset on the BS, so we need to make sure it’s reflecting changes (e.g., another asset on the pro-forma BS going up means we need less of a goodwill plug). Equity purchase price will be your fully diluted shares outstanding multiplied by the offer price. Shareholders’ Equity will be the Target’s Shareholders’ Equity (this will be subtracted given that it’s extinguished so won’t be on the pro forma balance sheet). The target’s existing goodwill, an asset, will be written down so pro-forma goodwill needs to go up to compensate. Tangible and intangible assets are written-up to their fair value, which will cause the asset-side of the pro-forma balance sheet to go up (so pro-forma goodwill needs to go down). The target’s existing DTL will normally be written down (so a liability is going down, thus the goodwill plug should go down to keep in balance). Existing DTAs are usually written down, although they can be rolled (but if they are written down that will necessitate goodwill going up). New DTL’s arising from the step-up in the tax basis from the asset write-ups will require goodwill to also go up to compensate (as pro-forma liabilities will go up, so you need a larger goodwill plug). Finally, if the company’s deal with each other (quite common if you’re dealing with a vertical integration) then you add intercompany A/R (as post-merger these are zero) and subtract intercompany A/P (as post-merger these are zero). The more practical Goodwill equation, that will almost always be fine to use in an interview would be: TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 27 Goodwill = Equity Purchase Price – Shareholders’ Equity + Target’s Existing Goodwill – Tangible and Intangible Asset Write-Ups + New DTL from the Transaction Note: If you haven’t already, you should do the accounting questions on asset write-ups and DTLs that I put together. 12. What’s the “total allocable purchase premium”? Just in case you’re asked, this is: Total Allocable Purchase Premium = Equity Purchase Price – Shareholders’ Equity + Target’s Existing Goodwill This is value reflects the excess (or premium) of the purchase price over the net identifiable assets of the company. When you’re modeling out asset write-ups, it’ll be as a percent of the total allocable purchase premium, not of the equity purchase price or the target’s total assets on their balance sheet. 13. Can you give me a more practical run through of how you create goodwill and how the total allocable purchase premium fits into this? The following is a more practical example of what you’ll be doing. In most cases the goodwill created won’t involve most of what’s in the “formal” equation for goodwill. Instead, it’ll usually just involve tangible and intangible asset write-ups plus the newly created new deferred tax liabilities. Keep in mind, however, that goodwill does act as a plug. If you’re out of balance, it’s probably because you’ve modeled something elsewhere that is not being reflected in goodwill. 14. Following up on this last question. Now that we’ve found our asset write-up amounts, how much additional D&A will hit our income statement on a book basis annually? How much will this save us in taxes on a book basis annually? Assuming a ten-year period and that we straight-line it, that’d be $42 per year of depreciation (from the tangible asset write-up) and $42 per year of amortization (from the intangible asset write-up). The tax benefit this would confer (how much taxes we’ll “save” due to enhanced D&A on a book basis) will be $16.8 per year assuming a 20% tax rate. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 28 15. What are the three primary kinds of transaction structures? There are three primary transaction types in the U.S. (the first two of which have more or less analogous parallels in every other jurisdiction). § Stock Sale Transaction A stock transaction involves the purchase of all the assets and liabilities of a target company. In essence, you’re acquiring everything about the company in its entirety. This is the way nearly all large-scale M&A transactions are structured. Importantly, the tax basis is not written up in a stock transaction, which is why we get the DTLs that come from tangible and intangible asset write-ups (because the new depreciation and amortization stemming from the book asset write-up is not reflected in the tax basis). Finally, unlike in an asset sale and a 338(h)(10) Election to be discussed, the seller only faces taxes on the transaction price in a stock sale transaction. § Asset Sale Transaction In an asset sale transaction, an acquirer is picking and choosing what assets and liabilities they want to assume. While you can certainly have large M&A deals structured as asset sales, it’s much rarer. However, there are some industries (like oil and gas) where this kind of structure is more popular even for larger transactions. In an asset sale any assets that are written-up by the acquirer will not create DTLs, as the tax basis will change so the new (larger) depreciation and amortization will be reflected on the tax income statement. In other words, there won’t be the kind of discrepancy between the book basis and tax basis that arises in stock sale transactions whereby you get the creation of DTLs. Further, in an asset sale you not only (as the seller) will be taxed on the transaction price, but you’ll also be taxed on the gains from the valuation of the assets sold over where they’re held on the books. So, the buyer gets the tax benefit of being able to truly write up assets (not just on a book basis, but on a tax basis), but the seller will have a greater tax burden than they would under a stock sale transaction. In an ideal world, acquirers would want every transaction to be an asset sale transaction as you could pick and choose what assets and liabilities you want to assume and write-up assets on a book and tax basis. However, sellers are (for obvious reasons) remiss to want this transaction type under most circumstances. § 338(h)(10) Election Sale This is a transaction style unique to the U.S. whereby assets that are written up by the acquirer will not result in the creation of DTLs, as the tax basis will be aligned with the book basis (just as is true with an asset sale). However, the difference with an asset sale is that all assets and liabilities (just like in a stock sale) are included in the transaction (in other words, there’s no picking and choosing going on). TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 29 So, this form of a transaction structure is a blend between an asset sale (where the tax basis is the same as the book basis for written-up assets) and a stock sale (where all assets and liabilities are assumed by the acquirer). The tax treatment (for the seller) in this transaction type is the same as for an asset sale (taxed on the transaction price and on the differential between the asset values and what they’re held on the books for). 16. Can you conceptually run me through why DTLs get created in M&A transactions? Do these always occur? We already covered this quite a bit in the accounting section, but let’s review it again in a bit more conceptual depth. You’ll get either DTLs or DTAs when a company is acquired in a stock sale, but not in an asset sale or 338(h)(10) election sale. DTLs are created when a company being acquired is carrying assets on their books for less than their fair market value. So, when these assets are reevaluated up to their fair market value by the acquirer the amount of depreciation (for tangible assets written up) or amortization (for intangible assets written up) is increased. This increased D&A, in turn, will lower the amount of pre-tax income and tax the company should be paying. However, importantly this is all on a book basis (for accounting purposes) not a tax basis (what you’re paying in cash taxes). On a tax basis, the asset write-ups are not being recognized and thus the enhanced D&A, and lower taxes owed, are not recognized either. It’s this discrepancy between the book basis (financial accounting) and tax basis (tax accounting) that leads to the creation of DTLs. The DTLs are a way of bridging this temporary discontinuity arising from differences in D&A, and what they represent is the need to pay higher taxes in the future because of the lower book basis taxes that are currently being recognized. Another way to conceptually think about the DTLs created through asset write-ups is that if we have an asset of $10 that we write-up to be worth $25, then the tax basis remains at $10, but for book purposes we now have an unrecognized gain of $15 that taxes have not been paid on (so the DTL can be thought of as representing the taxes owed on this gain, which are slowly recognized over time as the DTL is unwound). Note: See the accounting questions on how asset write-ups and DTLs flow through the three statements and I think you’ll get a better feel for this if things are still a bit confusing. Note: Asset write-downs, which create DTAs, are just the inverse of what was described above. Although in M&A transactions they’re rarer. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 30 17. Let’s say a company (ParentCo) has $1,000 in assets and $800 in liabilities. TargetCo has $100 in assets and $50 in liabilities. ParentCo acquires TargetCo for $400 using a 50/50 mix of cash and debt consideration (assume a stock sale transaction). Further, ParentCo writes-up the assets of TargetCo to $300. Can you walk me through the proforma BS? First, let’s just note the equity of ParentCo is $200 (in an interview you could note that the shareholders’ equity of TargetCo is $50, but it’ll be extinguished in the acquisition anyway). We’ll then combine the assets and liabilities of the two firms. So, we’ll have assets of $1,100 and liabilities of $850. We’re funding the acquisition with 50/50 cash and debt. So, cash will reduce our assets by $200 to $900 and the liabilities will grow (from new debt) to $1,050. We also have written up the book value of the assets of TargetCo to $300 (a $200 write-up in total). This asset write-up boosts the asset-side of the balance sheet up from $900 to $1,100. To calculate the DTL it’ll simply be $200*0.20 or $40 (assuming a 20% tax rate for ParentCo). So, now liabilities are up another $40 to $1,090. We also have the existing equity of ParentCo ($200), so the liabilities and shareholders’ equity side of the balance sheet is $1,290. The asset side is $1,100. So, the goodwill plug, within assets, will be $190 to give us balance. 18. Let’s say you acquire 80% of a company that is worth $200 using 50/50 cash and debt. It has $100 in assets, $50 in liabilities, and $50 in equity. How will the balance sheet end up looking? If you’ve already gone through the accounting questions, you should immediately recognize that we’ll need to be adding a noncontrolling interest line item on our balance sheet to reflect the portion of the company we don’t own (20%), but we’ll still need to consolidate the financials of both companies. First of all, what did we actually pay here? The company is worth $200, but we only bought 80% of it, so we paid out $160 (via $80 of cash on our balance sheet and raising $80 in new debt). So, on the assets side we have cash down $80, and we have acquired $100 in new assets (since we’re consolidating financials). So, assets before dealing with goodwill considerations are up $20. Note: We’re assuming no asset write-up here, but we could have one. The process for handling an asset write-up would be no different than what we went through in the prior question. On the liabilities side, we have liabilities up $50 from acquiring the company’s full liabilities and we have another $80 from issuing debt to fund the purchase. So, liabilities are up $130. While the equity of the acquirer company is wiped out, we need to reflect non-controlling interest on a line item within shareholders’ equity, which will be (20% * $200) or $40. So, the liabilities and shareholders’ equity side is up $170. Moving back to the asset side, assets are up by $20 so goodwill needs to be $150 in order to plug the difference (since L&SE are up $170) and thus have balance. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 31 19. Let’s say that ParentCo has an EV of $100, equity value of $80, debt of 80, cash of $60, EBITDA of $10, and net income of $6. It acquires TargetCo, which has an EV of $40, equity value of $40, EBITDA of $4, and net income of $2. If the acquisition was funded 100% by debt, at a 10% coupon, what is the pro-forma EV/EBITDA and P/E ratio? Alright, there’s quite a bit going on here. Let’s first work through what the combined EV will be. We have ParentCo EV of $100. We’ll assume TargetCo is acquired for its EV of $40, which will lead to a $40 debt increase (since we said the transaction is 100% funded by debt) so EV is up to $140 ($80 market cap of ParentCo + $80 debt of ParentCo + $40 new debt of ParentCo - $60 in cash). Note: Remember that conceptually the EV of TargetCo is being “captured” by the $40 increase in debt (given that we acquired it for $40). Note: Even if we used all cash, or all stock, or some combination of cash, stock, and debt the combined EV would not change. The combined EBITDA will be $14 as this is all before taking into account the interest associated with the new debt issuance. So, we can say that pro-forma EV/EBITDA will be $140/$14 or 10x. Moving on to P/E. The P (market cap) is unchanged at $80 (think back to the pro forma EV calculation if you’re wondering why). To find earnings, we can combine the net income together so we’ll have $6 + $2 or $8. However, we funded this transaction 100% with debt, so unlike EBITDA we do need to make adjustments here for interest expense. We have $40 in debt at a 10% coupon, so we have $4 in cash interest expense per year. Assuming a 20% tax rate, this causes a decline in combined net income of $3.2. Therefore, combined net income is $8 - $3.2 or $4.8. So, our P/E ratio is $80 / $4.8 or 16.67x (don’t worry about needing to give the exact multiple when the math isn’t straight forward, just saying $80 / $4.8 is perfectly fine). 20. What do we mean by an exchange ratio in M&A transactions? Normally when we think of stock compensation as part of an M&A transaction, we’re referring to the fact that ParentCo will issue new shares and use the cash proceeds from that issuance to buyout TargetCo’s shares at an agreed upon offer price (which is, for publicly traded targets, at a premium to where it’s currently trading). Another thing you could do is offer TargetCo a pro-rata amount of ParentCo’s shares directly as compensation. So, for example, if you’re ParentCo and you’re buying out TargetCo for $1,000,000 in a 100% stock deal, and ParentCo’s current share price is $20, then you’d offer them 50,000 shares of ParentCo. If TargetCo currently has 25,000 shares outstanding, then this would equate to an exchange ratio of 2.0x (meaning that every share of TargetCo would receive two shares of ParentCo as compensation). Of course, part of the issue with using an exchange ratio is that if you specify an exchange ratio, but then the price of ParentCo falls, then the cash equivalent compensation going to TargetCo is lessened (and vice versa). So, if ParentCo’s stock fell after the announced transaction to $15, then the implied compensation that TargetCo is getting would be: $15 * 2 * 25,000 = $750,000. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 32 Here’s a little illustration of how PJT represented what the implied exchange rate would be for a potential transaction. This is done to show the acquirer what exchange ratio (based on the current trading prices of both stocks) would need to be given to get to a certain dollar value. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 33 Valuation Questions 1. What are the three major types of valuation techniques? Which produces the highest valuation? As you likely already know, you have comps, precedents, and DCFs. All of these will almost always be used – unless it’s literally impossible to find comps, precedents, or to do a DCF – in order to develop a valuation range for a company. As I mentioned earlier in another question, when you don’t have as much confidence that a certain valuation methodology is giving you a true sense of a company’s worth you’ll often still include it (but emphasize the other methodologies that give a truer picture). Generally speaking, precedents will give you the highest valuation (as when a company is acquired, you’ll normally have a significant premium added to its current trading value if it’s public). Then you’ll normally have comps or the DCF as the next highest valuation. In very hot equity markets – like we’ve seen in 2021– usually comps reflect a higher valuation than you’ll get from a DCF (unless you’re aggressive in choosing an exit multiple for the DCF). 2. What other valuation techniques are common in TMT? The primary other type is Sum of the Parts (SOTP). This is because especially in the telecom and media space you’ll find companies that have a number of quite distinct business segments that should be valued individually. What this means practically is not doing a DCF for each individual segment, but rather applying comp multiples to the EBITDA thrown off by each of those segments to get an EV value for each segment. Then you add up all those segment EVs to get to an overall EV for the company. Below is an illustration for Sony, which has a number of very distinct business lines: TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 34 Another common type of analysis you’ll see in most M&A pitchbooks is premiums paid analysis. This is sort of a valuation technique, but is really more a way of demonstrating how much above the current trading price (for a public company) you’ll likely need to pay based on past precedence (so it gives you a “value” insofar as it tells you practically how much you’ll likely need to spend in excess of where a public company is currently trading). Here’s a real-world example from an Evercore pitchbook. Generally, you’ll compare the premium paid for companies in the same industry to the spot price just before the announcement, where it was trading a week before that, and where it was trading a month before that. Part of the reason why you don’t just look at spot is because rumors and speculation could spread about the TargetCo being a possible takeover target, which could lead to a reasonable rise in the share price as you’re working toward getting a deal done. Note: When doing premiums paid, you generally will be looking at a larger number of transactions that you would in comps or precedent transactions. The reason being that you don’t care as much about the companies used as being direct comparables, but rather are just looking to get a feel for how much over the market price companies are typically paying within the same industry segment. Note: When doing premiums paid analysis, you take the median value after dropping the outliers. So, for example, if you have a set of ten companies and the “1-Week Prior” premium for each company was 10%, 14%, 21%, 24%, 25%, 26%, 34%, 44%, 89%, and 109% you’d drop the 10%, 14%, 44%, 89%, and 109%. The median value of the remaining is 25%. This isn’t important to bring up in an interview at all. The reality is you’ll have an associate or VP tell you what outliers to cut or whether to take a median or mean based on their discretion. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 35 3. If you’re doing a SOTP analysis, would it ever make sense to use comp and precedent multiples for different divisions? No. You need to keep things apples-to-apples. If there are five distinct segments within the company you’re analyzing, and you use comp multiples (meaning: public companies that have not been acquired) for four segments, and a precedent multiple for one segment, then you’ll end up with an overly inflated value for that one segment. In other words, four segments will reflect pre-transaction multiples and one segment will reflect a true transaction multiple (that will have a premium embedded in it). 4. But wait, if we’re trying to find the true EV of a company with distinct business segments, shouldn’t we try to use precedent multiples (that reflect the true cost of acquiring a business) for each segment? In theory, yes, that’d be ideal. However, there are a few issues here in practice. First, it’ll likely be hard to find precedent transactions that fit each one of the distinct business segments of the company. Second, even if you find ideal precedent transactions, they’ll have all occurred at different times when equity markets were either quite hot (leading to higher multiples) or not. Why using comp multiples makes more sense is that they all reflect market multiples right now. Whereas with precedent multiples they reflect the multiple when the transaction occurred (which could have been many months ago and could perhaps not be representative of how the market is valuing companies in that segment today). 5. What about doing an LBO analysis? Is that common within TMT? An LBO analysis will (obviously!) be done when a sponsor (PE fund) buys a company. It’ll also often be done even if a strategic is buying a company just as another point to use in the football field analysis to show how various valuation methodologies come up with different values for the company. However, as you’d expect, an LBO analysis is not going to work well for all companies (in particular, for high-growth companies in tech that can’t handle having a robust capital structure with significant debt). 6. What’s the point of using all these valuation techniques? What do you show the client? From a junior banker perspective, you’ll be told what analysis to do (and re-do under different assumptions) and present the findings in a “football field”. A football field will list the methodologies used on the Y-axis and on the X-axis list the implied share price (if you’re looking at a public company) or the implied EV (if you’re looking at a private company). This football field will be placed in pitch decks for client meetings. The football field allows the client to quickly get a visual for what the approximate valuation range of their company (or the company they want to acquire). Remember: The EV (or implied share value) you’re getting from any analysis is not some objective reality. It’s just a rough indication of value. Here’s a real-world example from Evercore for a telecom. As you can see, they did comparables (what they call “public peer group”), precedents, a DCF, and also included premium paid. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 36 7. Let’s say that two companies in the media sector have the same EBITDA, but one sold for a 12x multiple while the other sold for 22x. What could explain this? § § § § § While the 12x company could be a legacy media company – with stable or declining growth – the 22x company may be relatively new with strong growth (and growth projections). The 12x company may have saturated a smaller or less lucrative segment of the market, while the 22x company has a foothold with room to grow in a larger or more lucrative segment of the market. The 12x company may have sold during a downtime for M&A, such as during the early part of the pandemic, while the 22x company sold just a year later during this incredibly robust M&A environment. Assuming we’re talking about non-GAAP EBITDA, the 12x company may have added back significant expenses that the 22x company didn’t (so even if they’re the same in every respect, the company that added back more will have a lower multiple as a result). The 12x company is just in an area of media – like radio – that has generally lower comp and precedent multiples than the 22x company. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 37 8. Many tech companies (and a few media ones) have no earnings to speak of, because they’re more or less in the pre-monetization / heavy-growth phase. How do you think about valuing them? The fact that a company has no earnings, or even no revenue, has no direct effect on comps or precedent transactions. You would just use a different type of multiple such as EV/Revenue or EV/MAUs, etc. as opposed to EV/EBITDA if the company you’re looking at has limited earnings. So, comps and precedents will be the valuation tools primarily relied upon. For companies that have just started to monetize then, depending on the scenario, a DCF could be used if you have some unlevered FCF and can come up with reasonable revenue growth projections (and let everything flow from that using static percentages for SG&A, COGS, etc.). The issue here is that for companies with minimal – but perhaps very fast growing – unlevered FCF, you’ll end up with a terminal value that comprises 90%+ of the EV found via the DCF. In other words, whatever the exit multiple you apply to year five EBITDA (or however long you project out) will really determine the EV today. 9. What’s future share price analysis? Some things in decks sent to clients are filler, to be honest. Future share price analysis involves projecting the potential share price of your company into the future by a year or two and then discounting it back to the present. With the assumption being that this will give you a better idea of what kind of premium would be reasonable to accept if someone is offering to buy you out (or what premium is reasonable to offer if you’re looking to acquire a company). Note: Premiums Paid Analysis, discussed in a prior question, also tells you how much premium you should offer, based on precedents, which is usually a much more reliable and realistic measure. All you do for future share price analysis is take the median P/E (you always use P/E) of public comparables. Then you apply the P/E you found to your future EPS (one or two years out). Then discount this back by a set of different discount rates around what your cost of equity is. Some of the issues with this are that P/E is a function of the overall market and you’re forecasting your future earnings (one or two years from now) against the current market conditions (that inform what the P/E ratios of public comparables are today). Here’s a page from a deck put together by Goldman laying out what’s often included on a page: TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 38 10. What is the process of calendarization all about? This is all pretty straight forward and mechanical, but I just wanted to cover it in case it ever came up. If the company your analyzing has a fiscal year end of June 30, but a comparable company has a year end of March 31, then you need to calendarize to have an apples-to-apples comparison to then analyze. Otherwise, you’d be comparing twelve-month periods that don’t perfectly overlap. So, to calendarize you’d just pretend that the comparable company you’re looking at has a year end of June 30 as well by taking their last fiscal year financials (from their 10K) and adding this year’s March 31 – June 30 period. Then you’d take off the last year’s March 31 – June 30 period. This leaves you with a 12-month period that’s aligned with our company’s fiscal year and allows for an apples-to-apples comparison. You’ll often hear the term TTM (trailing twelve months), which is just a term for the latest years’ financials. This is found (just as we went through in the example above) by taking the most recent fiscal year (from the 10K), adding the latest quarter(s), and then subtracting the equivalent quarter(s) from the last fiscal year. This leaves us with the most recent twelve-month period that’s been reported. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 39 11. What changes when we’re looking at coming up with a valuation for a private company? Especially in the tech space, we’ve seen companies staying private for longer even at valuations that stretch into the tens of billions. Philosophically the process of valuing a company that’s private isn’t any different than valuing one that’s public. You’ll still be able to use precedents, comps, and a DCF. But there will be a few wrinkles thrown in. § § § § Comps analysis. In the old days, the general rule of thumb is that you’d discount public comps because they’re liquid while private companies are per se not. Today it’s largely recognized that with so many bidders for private companies there’s not going to be a meaningful “liquidity” discount. Precedents analysis. Here there will be no change. Just as public shareholders will demand a premium in order to get a deal done, so too will those who control a company that’s private in an abstract way. So, there’s absolutely no discount applied or change to this analysis. In fact, private transactions for hot tech companies can come in quite a bit richer (meaning: at higher valuations) than their corresponding public precedent comparables because of the more concentrated share base. This is because the founder and initial VCs will hold such a large percent of equity that they often need a large offer to be tempted to sell (given that they’re the truest believers in the company). DCF. In a DCF the primary issue (assuming you already have access to the financials of the private company!) will be estimating what the WACC will be. While cost of debt and the overall D/E ratio will be easy to figure out, we’re left with the issue of estimating cost of equity given that the company won’t have a beta (since it’s not public). Normally you’ll just pull the cost of equity of comps and use that. Remember that you’ll always sensitize the EV found from a DCF with various WACCs anyway; so getting the WACC exactly right isn’t too important as long as you’re showing what the EV will be under various reasonable discount rates. Premiums Analysis. It goes without saying that given that the company isn’t public, any analysis that begins with what the current equity trading price is will be non-sensical. When answering this question, it’s a good idea to frame it properly. You want to show the interviewer that you understand that we don’t care about getting an implied equity price from our analysis, but rather are focused on figuring out what the overall EV is (in other words, what we’re going to have to pay for the company) since we aren’t needing to solicit the approval of a vast diversity of public shareholders. 12. Would you rather have $1,000 today or $100 a year forever? This is more of a little brainteaser, but worth going over quickly. When you read “forever”, you should think “perpetuity”. Recall that the PV of a perpetuity is the cashflow ($100) divided by the discount rate. So, if we set up our formula, we’d have $1,000 = $100 / r. Rearranging to isolate for r we’ll have $100 / $1,000 or 10%. Therefore, any discount rate above 10% would lead us to want the $1,000 today. Any discount rate below 10% would lead us to want $100 forever. So, our answer as to which one we want will be contingent on the discount rate. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 40 LBO Questions Note: Personally, I think the most efficient way to prepare for LBO questions is to go through a paper LBO (provided in question #3) and think through how you’d make it more realistic. 1. What’s an LBO and are they common in the TMT space? A leveraged buyout is an acquisition style used by sponsors (PE Funds) whereby they i) buy a company ii) place a significant amount of debt on it iii) sweep FCF from the company in order to pay down debt during the hold period (which is usually 5-7 years) iv) and sell at the end of the hold period for (hopefully) the same of greater EBITDA multiple than they purchased it for. The reality is that through the 1990s and 2000s (prior to the great financial crisis) the characterization of LBOs as involving putting as much debt on a company as it can bear and making as many cost cuts as possible was mostly true (TXU is one of my favorite examples from just prior to the financial crisis and back when investment banks like Goldman took lead roles in doing LBOs themselves). Today, the PE space has matured a great deal. Operating under the same model as through the ‘90s and ‘00s is just not overly viable today because i) there aren’t many companies left that fit the mold needed to aggressively lever up and cut costs and ii) there’s so much competition in the PE space now that you have to add some value, or have some unique angle, to get a meaningful return (IRR). Within TMT, it’s rare to see buyouts (LBOs) in the telecom space (because it’s almost invariably capex heavy and a very technical area) and within certain areas of tech (like semiconductors, where the same issues arise as in the telecom space). Within media, it’s a bit hit or miss and largely depends on whether the media company has relatively stable FCFs. Within tech, you may be surprised to know how popular LBOs are in the software space (largely due many companies predictable cashflows, especially for areas like B2B SaaS). Note: Within the Telecom Guide, Media Guide, and Tech Guide I get more into what sponsors look for in these segments and who some of the larger players are (within tech there are some dedicated tech sponsors, the most famous of which would be Vista). 2. If I were to ask you to do a quick LBO for me, what steps would you take? First, you’d lay out the assumptions. At a minimum, you should include LTM Revenue, LTM EBITDA, cash, the entry and exit multiple, the amount of debt being used and its cost, the tax rate, growth assumptions (either revenue or EBITDA), and then what you need for getting levered FCF (D&A, capex, and NWC changes). Second, you’d calculate your entry EV and equity value (equity value representing the cash the sponsor put into this investment). Third, you’d put together a quick income statement using the assumptions laid out in the first step, getting to net income. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 41 Fourth, you’d put together a quick “cashflow statement”, which is really just aimed at getting to levered FCF. Here you can either assume you keep all accumulated cash on the balance sheet or that you sweep it all to pay down debt. Fifth, you’d calculate your exit EV and equity value (equity value representing the cash the sponsor gets out of this investment after the hold period). Finally, you’d calculate your cash return (also called the MOIC or the cash-on-cash return) and your IRR. Your cash return will just be your exit equity value divided by the initial equity value. Below is a paper LBO question. The best way to learn the basic mechanics of an LBO, which is more than sufficient for interview purposes, is by taking a stab at a paper LBO. While a lot of nuances are left out of short paper LBOs, it’ll give you a feel for how an LBO is structured and how cash moves. 3. Let’s assume that we’re looking at a company with LTM revenue of $200M and with $50 in EBITDA (we’ll assume the EBITDA margin doesn’t change throughout the hold period). We can buy the company for a 6x EBITDA multiple and use a 75% / 25% debt-to-equity split and sell it for a 5x multiple after five years. We assume there will EBITDA growth of 10% each year over the hold period, the cost of debt will be 10%, and that we just accumulate any excess cash on our balance sheet instead of paying down debt or providing ourselves a dividend. The tax rate is assumed to be 20% and there will be annual D&A and capex of $20M each along with $5M in NWC. What would the cash return and IRR be on this deal? Is this a deal we should enter? Here we’ll follow the steps as outlined in the last question. We’ll start by laying out our assumptions from the question, then create our entry values, do a very basic IS and CFS to get what we need (net income and levered FCF, respectively), calculate our exit values, and then finally find our cash return and IRR. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 42 4. Is this paper LBO realistic? How could it be made more realistic? First of all, it’s increasingly common but still very rare that you’ll get a paper LBO in a summer analyst interview. For full-time interviews, it’d be slightly more common (but will occur much less than 50% of the time). The reason why paper LBOs are uncommon – unless you’re interviewing for an actual PE position – is just that most interviewees will have no idea how to even approach answering it, so it just becomes a bit awkward. If you are given a paper LBO, it needs to be something that you can reasonably do during the interview itself. So, the level of complexity in what I’ve shown above is more than enough even though we’ve made many simplifying assumptions. Some of these simplifying assumptions are: TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 43 § § § § § § We’re assuming that we just hold cash on the balance sheet and then get it at the end, as opposed to using it to pay down debt or dividend out cash to ourselves at the end of each year (if we had dividended out cash to ourselves that would’ve bumped up our IRR). We aren’t doing any asset write-ups and creating DTLs. We are assuming a static level of D&A throughout. We haven’t built any kind of debt schedule. So, we haven’t specified what kinds of debt we’re talking about here. For example, we haven’t shown there’s a revolver (which we be drawn in the advent of levered FCF being negative to get to our minimum cash balance). We have assumed there’s no cash that the company has when purchased, and we haven’t shown that there is a minimum cash balance of any kind that the company needs to maintain. We haven’t assumed that there are any financing or transaction fees involved (which there most certainly are in the real world!). Of course, there’s also the reality that we haven’t put together any form of balance sheet. We’re just making assumptions about the major balance sheet changes over time (e.g., NWC). However, it’s not entirely abnormal when you’re in a hurry to glaze over your balance sheet. 5. Can you rank what will improve a sponsor’s IRR the most? § § § First would be either having a lower entry multiple or having a higher exit multiple (since these are going to be the largest cash outflows and inflows). Second would be being able to use more leverage (debt) and placing a smaller equity piece (placing more debt will make equity returns more volatile, yes, but assuming the company doesn’t end up needing to restructure it will likely enhance returns). Third would be making income statement improvements (e.g., increasing revenue growth, increasing EBITDA margins, lowering COGS / SG&A, etc.) or cashflow improvements (e.g., lowering annual capex spend, having lower interest payments on debt). These are just general rules of thumb. Of course, having very strong revenue growth may eclipse the benefits of just lowering your entry multiple by 0.5x, etc. Tip: It would be really impressive in an interview to bring up the fact that sponsors generally care most about things that are definitive, not things that could potentially happen. So, for example, it’s very hard to predict if you can really enhance revenue by changing up your sales practices, but it can be quite easy to predict pre-transaction that you can cut capex down just by studying the business. 6. What do you think a sponsor looks for in a target in the TMT space? For a buyout to functionally work there are three prerequisites that you absolutely need regardless of the industry. § § The target needs to have relatively stable and predictable cashflows that will allow for the increased cash interest payments (stemming from the new debt placed on the company) to be made. The target needs to be in a relatively stable sub-segment that is not prone to disruption or obsolescence over the near term (or for a shift in investor sentiment that leads to a much lower exit multiple than the entry multiple). TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 44 § The target doesn’t need large amounts of ongoing capex in the future and there is not the risk of significant legal liability due to the nature of the product being sold. Some more TMT-specific prerequisites would include: § § § If the target sells a technically complicated good or service, the sponsors must have strong confidence in the existing management team (or feel they have ideal individuals to bring into the company). The target should have a reasonably diverse client base and a track record of both customer retention and customer acquisition. The target should have at least some level of pricing power (meaning: the ability to increase prices), which is why B2B SaaS is such a popular target for many tech sponsors. 7. What kind of debt mix is often used in an LBO? The capital structures used in buyouts have generally become quite a bit simpler over the past five years. Primarily due to the rise of the levered loan market, private credit / direct lending shops, etc. that allow for bigger pieces of senior secure debt to be placed (as opposed to needing to issue smaller tranches of unsecured and subordinated notes to get to your total desired debt). Generally, every LBO will come along with a revolver and at least one term loan (usually a TLB). A revolver is somewhat like a credit card with a set credit limit. So, for example, you could have a $200m revolver that is just cash that you do not currently have, but that you can draw at any time until the maturity of the revolver (which is typically five years). Revolvers sit at the top of the capital structure and will be backed fully by assets (usually a % of the company’s reasonably liquid assets, which is referred to as the borrowing base). To keep with our $200m revolver example, you would have two interest rates associated with it: an interest rate for the money you’ve drawn off of the revolver (e.g., maybe you did a $20m draw sometime during the first year, which has an L + 300bps interest rate) and an overall commitment fee (usually 20-50 basis points), which is multiplied by the unused portion of the revolver. So, if we have a $200m revolver with $20m drawn then our annual expense would be: $20m*(L+300bps) + $180m * (20bps). Think of the commitment fee as just being the price you pay for the right, but not the obligation, to draw money in the future. The purpose behind the revolver is for the company to have access to cash if necessary. For example, during the onset of the pandemic almost all companies began drawing down on their revolver to keep excess cash on the balance sheet. Below the revolver you have term loans. Generally, there will either be a first-lien term loan (TLA or TLB) or a second-lien term loan. Term loans are fully secured and will have a floating interest rate (e.g., Libor + 300 basis points). Term loans will generally make up the vast majority of the new capital structure (often 70-100%). The most frequent kind of term loan you’ll see for an LBO is a TLB, which is a first-lien loan that normally has amortization of 100bps a year and will be widely syndicated upon issuance (and generally permits the debtor to pay back some of the principal amount early). Revolvers and term loans make up the secured debt part of the capital structure. As mentioned, not all LBOs will include unsecured debt these days. However, if you do (as is still common) it’ll TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 45 be primarily in the form of senior notes. These will always be quite a bit smaller in size than the term loans, have a fixed interest rate, and a longer maturity than the term loans (because term loans will not accept a lower part of the capital structure coming due before themselves). I’m leaving out a lot of details here, but for interview purposes this is more than enough. In case you’re wondering about covenants, most term loans in today’s environment are going to be covlite and the most important aspects of them will surround leverage ratio requirements, additional permitted indebtedness language, and maybe a FCCR requirement. You can look up some term loan credit docs if you’d like to see more of the language surrounding the actions a company can’t take (e.g., permitted indebtedness, restricted cash, asset transfers, etc.). Here’s a pretty standard TLB credit doc: https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1657853/000110465916131559/a1614596_1ex10d7.htm Some things you can CTRL + F for include “pricing grid” to see how the TL is priced (as is common, it will fluctuate based on the leverage of the company) and “optional prepayment” (to see the language surrounding paying down early). You can also look at the “Affirmative Covenants”, which describe all the things the company must do to keep in compliance and the “Negative Covenants” which describe all the things the company must not do in order to keep in compliance. Practically speaking this all gets well beyond the scope of what you’re ever going to be asked in an interview. I’m just providing this in case you have some spare time and want to poke around a credit doc for fun (you can be the judge of how fun it is!). 8. How would you think about how much cash is available for optional debt repayment (doing a cash flow sweep) each year for an LBO? Remember that cash interest expense will already be reflected on the income statement and within cash flow from operations. So, when it comes to determining how much cash is available to repay debt principal annually (beyond what we are contractually obligated to do), we can just use cashflow from operations, subtract cashflow from investing, and subtract mandatory debt repayment. Optional Debt Repayment = CFO – CFI – Mandatory Debt Repayment Note: Practically speaking, you’ll also build into your model some minimum cash balance (e.g., $10M) so you won’t be sweeping all your cash out. You’ll also have the binding constraint of nocall provisions within certain types of debt (always in bonds) that precludes being able to repay early unless you do so at a higher rate (e.g., to call the debt early, you might have to take it out at $103 not at par). 9. What would the pro-forma balance sheet of a company that’s been bought out look like? On the assets side you’ll have cash down (as the excess cash that was on the balance sheet of the company pre-transaction will be used to finance the transaction), assets will be written-up so will increase in value, we’ll have a new line item for “deferred financing fees” since we’re going to TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 46 capitalize financing fees, and we’ll have goodwill that operates as our plug in the pro-forma balance sheet. On the liabilities side, all the debt of the company pre-transaction will be taken out and replaced with the new debt of the company (which will almost certainly be more than it was pretransaction). We’ll also now have DTLs stemming from the asset write-ups undertaken. Within shareholders’ equity, the equity of the company pre-transaction will be entirely wiped out and replaced by the equity / cash put in by the sponsor. 10. What would the projection of the pro-forma income statement of a company that’s been bought out look like? What are the major changes? Let’s work through it from the top down. We aren’t going to do anything to revenue, except bake in a percent growth over our holding period (which probably won’t be too different than the historical rate, in order to be conservative). We’ll probably hold COGS at the same percent of revenue, unless there’s a compelling reason to change it (for example, maybe we know a certain supplier well and thus feel we can reduce one of the areas of COGS down). We’ll take down SG&A by whatever our cost synergies (cost savings) are projected to be. However, we’ll increase SG&A by the “Sponsor management fee”, which is a fee that the company pays the PE fund for the general consultancy, help, etc. it’s providing. This is just another way in which the PE fund can extract a bit of cash before exit and is usually a very small amount in the grand scheme of things (although some sponsors are more aggressive in charging for their “services”, which is a source of controversy). This all leads us to EBITDA. Below EBITDA is where the largest changes will occur. Depreciation and amortization will go up due to the asset write-ups that occur (as we’ve already discussed extensively elsewhere). We’ll also have “Amortization of deferred financing fees” or “Amortization of capitalized financing fees” (they mean the same thing) due to the fact that we’ll be capitalizing financing fees since we will benefit from these over the duration of the holding period (so the amount of annual amortization stemming from financing fees, which will be straight lined, will hit the income statement). Then we’ll normally have quite a granular “interest expense” section, detailing all of our tranches of debt and the amount of interest (cash or PIK) associated with each. We’ll often also have a separate line item for our “Commitment fee on unused revolver”, which is the amount we pay for having the right to draw down our revolver (even if it’s only partially drawn). Finally, within the interest expense section, we’ll have an “Admin agent fee”, which is an annual flat fee (usually 5-15bps multiplied by the amount of the revolver and/or non-syndicated term loan). This is a fee paid to the bank who has originated the revolver (or non-syndicated term loan) to handle the general administration of it. Almost like how most credit cards come along with a flat annual fee to partly offset the costs of making the card, customer service, etc. After we’ve handled interest expense and these other debt-related fees, we’re at earnings before tax. We then simply apply the tax rate, as per normal, and get to net income. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 47 11. What’s the potential downside from reducing capex as much as possible in order to increase the amount of cash available for optional debt repayments during the hold period? There is an argument to be made that reducing capex could reduce revenues in future years. For example, if you aren’t investing in upgrading stores then customers may be less likely to shop there in the future. However, the primary issue will be that when you’re trying to exit after the hold period, you may get a lower multiple than you anticipated (perhaps much lower than your entry multiple), because buyers will look at the company and note the need to increase capex substantially. Sponsors need to walk a fine line between harvesting as much cashflow as possible during the hold period and ensuring that the business isn’t hollowed out or cash flow starved by the time they go to flip it after the hold period. 12. What are the two investment return metrics that will always be calculated in an LBO model? The two metrics, that are linked together, are the cash return (sometimes called the multiple on invested capital, MOIC, or the cash-on-cash return) and the internal rate of return (IRR). All the cash return involves is taking the equity value at exit and then dividing it by the initial equity value (the cash invested into the business when it was acquired). In other words, what the cash return says is basically, “Let’s forget about anything related to discounting. Let’s just figure out how much cash we invested in the firm initially and how much we’ve got out of the firm at exit.” The IRR implicitly takes discounting into consideration. After all, making double your money is great, but it’s much better to double your money in a year than in twenty years. The IRR is a percentage that shows what the discount rate would need to be to make the net present value (NPV) of all your cash flows zero. More practically, you can think about IRR as being the interest rate you’d need to get - on the initial amount of cash invested into the company, compounded annually - in order to have the same return as this investment has given you. So, as you’d expect, while your cash return can stay constant your IRR can vary wildly depending on how many years we’re talking about. For example, if you have a 2x cash return within five years, then you’d have a 26% IRR. However, if you have a 2x return in ten years, you’d have just a 7.2% IRR. Note: You can play around with IRR calculations yourself using the =IRR function in Excel. 13. What is the kind of IRR that sponsors look for in an investment in the TMT space? Generally, anywhere from a 15-30% IRR over a five-to-seven-year hold period will be enticing. Ultimately, the return from making an illiquid and concentrated buyout bet needs to give a reasonable level of expected return above what you could get through a liquid and diversified pool of comparable public companies. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 48 14. Let’s say a company puts in a $200M equity chunk at time zero. In year five, the equity value is $600M. What’s the cash return and IRR? The cash return would simply be 3x. The IRR would be 24.6% where you have an outflow of $200M at time zero and, five years later, a cash inflow of $600M. It’s a good idea to have memorized a few IRRs for year five (as you obviously can’t do them in your head). 2x in five years will correspond to an IRR of 14.9%, 3x in five years will correspond to an IRR of 24.6%, and 4x in five years will correspond to an IRR of 32%. A quick mental math trick is to know the rule of 72, which simply says that 72 divided by the number of years will tell you the IRR you’d get assuming a 2x cash return. So, for example, if I were to ask you what the IRR would be if we had a 2x cash return in four years, you could guess the IRR is around 18% (72/4). Likewise, if I were to ask you what the IRR would be if we had a 2x cash return in three years, you could guess the IRR would be around 24% (72/3). The rule of 114 is similar, except for finding the IRR for a 3x cash return. So, if I were to ask you what the IRR is based on a 3x cash return in five years you’d say 23% (the real answer is 28%, but at least we’re in the ballpark!). 15. Keeping with our prior question, what would the cash return and IRR be if we did a dividend recap of $50M in year two and three, which corresponds with the equity value at exit being $100M lower? So, we know that our original IRR was 24.6%. There’s no way you could do the math of how this works in your head. You’ll just be expected to know that getting cash sooner is better and as a result even though the equity value at exit is lower (meaning: the cash being returned to the PE fund) this is more than made up for by getting $50 in year two and three. If you want to try this out yourself in Excel, you should expect a see an IRR of 28% with $200M of cash outflow in year zero, $50M cash inflows in year two and three, and then a $500M cash inflow in year five. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 49 16. If the initial entry multiple into an investment was 9x, what do you think the exit multiple would have to be to earn a 20%+ IRR? This is a bit of a trick question. Generally, in LBO models you’ll assume that the company is sold at exit for the same EBITDA multiple as it was bought at or a lower one. In fact, you will usually create sensitivity tables showing what the IRR will be based on i) the exit year and ii) the exit multiple (being both higher and lower than the entry multiple). While you may think that the exit multiple must be higher than the entry multiple to get a 20%+ IRR, it could have been the result of any (or all) of the following: § § § § Significant debt paydown in the first five years (making equity value higher). Significant revenue growth (which boosts EBITDA). Significant dividends out to the sponsor. Significant cost cutting (which also boosts EBITDA). The “magic” of LBOs is the fact that you do not need to rely on having a higher exit multiple than your entry multiple. In fact, you can often have a 0.5x or 1x lower multiple on exit and still have achieved a ~20% IRR. 17. In one of our prior questions reference was made to dividend recaps. How do they differ from a traditional dividend? A traditional dividend is simply when a company decides to pay back some of its retained earnings to shareholders. So, in other words, the company has accumulated a stockpile of cash, decides it really doesn’t have good internal use for it (e.g., M&A, spending on capex, etc.), and decides to just give it back to shareholders. A dividend recap involves a company going and raising additional debt for the sole purpose (or at least the primary purpose) of paying out the cash proceeds as a dividend to its shareholders (in the case of an LBO, the shareholders are just the sponsor). The rationale for doing this is that, as we discussed in the questions above, it’s better to get cash early rather than later. So, if a sponsor is very pleased with the performance of one of its investments and thinks it can handle more leverage (debt) than it’ll take the opportunity to do a dividend recap to begin getting a true cash return on its investment. To be clear, a company that has been bought out by a sponsor may provide traditional dividends as well. For example, if the company has $40M in cashflow for optional repayment (as we talked about calculating in a prior question), but only has the ability to pay back $30M this year in debt according to the credit docs, then it has the choice of either keeping that cash on the books, investing it within the company, or issuing a normal dividend back to the PE fund. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 50 18. In a full LBO model, what tabs are generally created? Generally, you’ll have: § § § § § § A transaction summary tab which is a high-level overview of the transaction structure, capital structure, annual free cash flow projections, and returns. A pro-forma income statement. A pro-forma balance sheet. A pro-forma cashflow statement. A debt schedule, which lays out in more detail the debt structure and the amount of cash available for optional repayment (plus what debt was paid down with this excess cash). A return analysis tab, which shows what your cash return and IRR would be if you were to sell the business in any year over the projected hold period (so you’ll make an exit multiple assumption to get to EV, then take off the current debt and add cash to get to equity value and divide that by your original equity value). You’ll then create sensitivity tables showing your IRR if you were to exit at various years and at various exit multiples (I showed a copy of a sensitivity table doing this in a prior question). 19. So, a large part of what drives a favorable IRR is leverage. But can there be too much leverage? Absolutely. Because of how levered these companies are they are also a prime candidate for needing to restructure in- or out-of-court. Out-of-court restructuring usually involves changing the terms of existing debt in the capital structure (perhaps providing debt holders cash or equity to consent to changing the terms of their debt). This naturally dilutes down any potential IRR for the sponsor. In-court restructuring (going through the Chapter 11 process in the U.S.) will involve equity holders (the sponsors) being almost certainly wiped out and with existing debt holders then taking control of the company as it emerges from bankruptcy. Because the sponsor has equity – residing at the bottom of the capital structure – that both enhances returns assuming that a company can meet its cash interest payments and not breach debt covenants, but it also means that the sponsor is the first group of holders to take a loss when things turn south. TMTBanking.com Adv. Valuation Q&A 2021-2022 All Rights Reserved 51