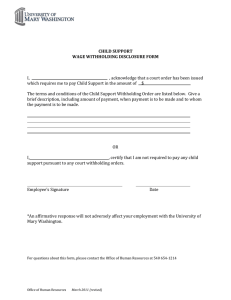

G.R. No. 172231 February 12, 2007 COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL CORPORATION, Respondent. REVENUE, Petitioner, vs. ISABELA CULTURAL DECISION YNARES-SANTIAGO, J.: Petitioner Commissioner of Internal Revenue (CIR) assails the September 30, 2005 Decision1 of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 78426 affirming the February 26, 2003 Decision2 of the Court of Tax Appeals (CTA) in CTA Case No. 5211, which cancelled and set aside the Assessment Notices for deficiency income tax and expanded withholding tax issued by the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) against respondent Isabela Cultural Corporation (ICC). The facts show that on February 23, 1990, ICC, a domestic corporation, received from the BIR Assessment Notice No. FAS-1-86-90-000680 for deficiency income tax in the amount of P333,196.86, and Assessment Notice No. FAS-1-86-90-000681 for deficiency expanded withholding tax in the amount of P4,897.79, inclusive of surcharges and interest, both for the taxable year 1986. cannot be considered as a final decision appealable to the tax court. This was reversed by the Court of Appeals holding that a demand letter of the BIR reiterating the payment of deficiency tax, amounts to a final decision on the protested assessment and may therefore be questioned before the CTA. This conclusion was sustained by this Court on July 1, 2001, in G.R. No. 135210.8 The case was thus remanded to the CTA for further proceedings. On February 26, 2003, the CTA rendered a decision canceling and setting aside the assessment notices issued against ICC. It held that the claimed deductions for professional and security services were properly claimed by ICC in 1986 because it was only in the said year when the bills demanding payment were sent to ICC. Hence, even if some of these professional services were rendered to ICC in 1984 or 1985, it could not declare the same as deduction for the said years as the amount thereof could not be determined at that time. The CTA also held that ICC did not understate its interest income on the subject promissory notes. It found that it was the BIR which made an overstatement of said income when it compounded the interest income receivable by ICC from the promissory notes of Realty Investment, Inc., despite the absence of a stipulation in the contract providing for a compounded interest; nor of a circumstance, like delay in payment or breach of contract, that would justify the application of compounded interest. Likewise, the CTA found that ICC in fact withheld 1% expanded withholding tax on its claimed deduction for security services as shown by the various payment orders and confirmation receipts it presented as evidence. The dispositive portion of the CTA’s Decision, reads: The deficiency income tax of P333,196.86, arose from: (1) The BIR’s disallowance of ICC’s claimed expense deductions for professional and security services billed to and paid by ICC in 1986, to wit: (a) Expenses for the auditing services of SGV & Co.,3 for the year ending December 31, 1985;4 (b) Expenses for the legal services [inclusive of retainer fees] of the law firm Bengzon Zarraga Narciso Cudala Pecson Azcuna & Bengson for the years 1984 and 1985.5 (c) Expense for security services of El Tigre Security & Investigation Agency for the months of April and May 1986.6 (2) The alleged understatement of ICC’s interest income on the three promissory notes due from Realty Investment, Inc. The deficiency expanded withholding tax of P4,897.79 (inclusive of interest and surcharge) was allegedly due to the failure of ICC to withhold 1% expanded withholding tax on its claimed P244,890.00 deduction for security services.7 On March 23, 1990, ICC sought a reconsideration of the subject assessments. On February 9, 1995, however, it received a final notice before seizure demanding payment of the amounts stated in the said notices. Hence, it brought the case to the CTA which held that the petition is premature because the final notice of assessment WHEREFORE, in view of all the foregoing, Assessment Notice No. FAS-1-86-90-000680 for deficiency income tax in the amount of P333,196.86, and Assessment Notice No. FAS-1-86-90-000681 for deficiency expanded withholding tax in the amount of P4,897.79, inclusive of surcharges and interest, both for the taxable year 1986, are hereby CANCELLED and SET ASIDE. SO ORDERED.9 Petitioner filed a petition for review with the Court of Appeals, which affirmed the CTA decision, 10 holding that although the professional services (legal and auditing services) were rendered to ICC in 1984 and 1985, the cost of the services was not yet determinable at that time, hence, it could be considered as deductible expenses only in 1986 when ICC received the billing statements for said services. It further ruled that ICC did not understate its interest income from the promissory notes of Realty Investment, Inc., and that ICC properly withheld and remitted taxes on the payments for security services for the taxable year 1986. Hence, petitioner, through the Office of the Solicitor General, filed the instant petition contending that since ICC is using the accrual method of accounting, the expenses for the professional services that accrued in 1984 and 1985, should have been declared as deductions from income during the said years and the failure of ICC to do so bars it from claiming said expenses as deduction for the taxable year 1986. As to the alleged deficiency interest income and failure to withhold expanded withholding tax assessment, petitioner invoked the presumption that the assessment notices issued by the BIR are valid. The issue for resolution is whether the Court of Appeals correctly: (1) sustained the deduction of the expenses for professional and security services from ICC’s gross income; and (2) held that ICC did not understate its interest income from the promissory notes of Realty Investment, Inc; and that ICC withheld the required 1% withholding tax from the deductions for security services. presents largely a question of fact; such that the taxpayer bears the burden of proof of establishing the accrual of an item of income or deduction.17 The requisites for the deductibility of ordinary and necessary trade, business, or professional expenses, like expenses paid for legal and auditing services, are: (a) the expense must be ordinary and necessary; (b) it must have been paid or incurred during the taxable year; (c) it must have been paid or incurred in carrying on the trade or business of the taxpayer; and (d) it must be supported by receipts, records or other pertinent papers.11 Corollarily, it is a governing principle in taxation that tax exemptions must be construed in strictissimi juris against the taxpayer and liberally in favor of the taxing authority; and one who claims an exemption must be able to justify the same by the clearest grant of organic or statute law. An exemption from the common burden cannot be permitted to exist upon vague implications. And since a deduction for income tax purposes partakes of the nature of a tax exemption, then it must also be strictly construed. 18 The requisite that it must have been paid or incurred during the taxable year is further qualified by Section 45 of the National Internal Revenue Code (NIRC) which states that: "[t]he deduction provided for in this Title shall be taken for the taxable year in which ‘paid or accrued’ or ‘paid or incurred’, dependent upon the method of accounting upon the basis of which the net income is computed x x x". Accounting methods for tax purposes comprise a set of rules for determining when and how to report income and deductions.12 In the instant case, the accounting method used by ICC is the accrual method. Revenue Audit Memorandum Order No. 1-2000, provides that under the accrual method of accounting, expenses not being claimed as deductions by a taxpayer in the current year when they are incurred cannot be claimed as deduction from income for the succeeding year. Thus, a taxpayer who is authorized to deduct certain expenses and other allowable deductions for the current year but failed to do so cannot deduct the same for the next year.13 The accrual method relies upon the taxpayer’s right to receive amounts or its obligation to pay them, in opposition to actual receipt or payment, which characterizes the cash method of accounting. Amounts of income accrue where the right to receive them become fixed, where there is created an enforceable liability. Similarly, liabilities are accrued when fixed and determinable in amount, without regard to indeterminacy merely of time of payment.14 For a taxpayer using the accrual method, the determinative question is, when do the facts present themselves in such a manner that the taxpayer must recognize income or expense? The accrual of income and expense is permitted when the all-events test has been met. This test requires: (1) fixing of a right to income or liability to pay; and (2) the availability of the reasonable accurate determination of such income or liability. The all-events test requires the right to income or liability be fixed, and the amount of such income or liability be determined with reasonable accuracy. However, the test does not demand that the amount of income or liability be known absolutely, only that a taxpayer has at his disposal the information necessary to compute the amount with reasonable accuracy. The all-events test is satisfied where computation remains uncertain, if its basis is unchangeable; the test is satisfied where a computation may be unknown, but is not as much as unknowable, within the taxable year. The amount of liability does not have to be determined exactly; it must be determined with "reasonable accuracy." Accordingly, the term "reasonable accuracy" implies something less than an exact or completely accurate amount.[15] The propriety of an accrual must be judged by the facts that a taxpayer knew, or could reasonably be expected to have known, at the closing of its books for the taxable year.[16] Accrual method of accounting In the instant case, the expenses for professional fees consist of expenses for legal and auditing services. The expenses for legal services pertain to the 1984 and 1985 legal and retainer fees of the law firm Bengzon Zarraga Narciso Cudala Pecson Azcuna & Bengson, and for reimbursement of the expenses of said firm in connection with ICC’s tax problems for the year 1984. As testified by the Treasurer of ICC, the firm has been its counsel since the 1960’s.19 From the nature of the claimed deductions and the span of time during which the firm was retained, ICC can be expected to have reasonably known the retainer fees charged by the firm as well as the compensation for its legal services. The failure to determine the exact amount of the expense during the taxable year when they could have been claimed as deductions cannot thus be attributed solely to the delayed billing of these liabilities by the firm. For one, ICC, in the exercise of due diligence could have inquired into the amount of their obligation to the firm, especially so that it is using the accrual method of accounting. For another, it could have reasonably determined the amount of legal and retainer fees owing to its familiarity with the rates charged by their long time legal consultant. As previously stated, the accrual method presents largely a question of fact and that the taxpayer bears the burden of establishing the accrual of an expense or income. However, ICC failed to discharge this burden. As to when the firm’s performance of its services in connection with the 1984 tax problems were completed, or whether ICC exercised reasonable diligence to inquire about the amount of its liability, or whether it does or does not possess the information necessary to compute the amount of said liability with reasonable accuracy, are questions of fact which ICC never established. It simply relied on the defense of delayed billing by the firm and the company, which under the circumstances, is not sufficient to exempt it from being charged with knowledge of the reasonable amount of the expenses for legal and auditing services. In the same vein, the professional fees of SGV & Co. for auditing the financial statements of ICC for the year 1985 cannot be validly claimed as expense deductions in 1986. This is so because ICC failed to present evidence showing that even with only "reasonable accuracy," as the standard to ascertain its liability to SGV & Co. in the year 1985, it cannot determine the professional fees which said company would charge for its services. ICC thus failed to discharge the burden of proving that the claimed expense deductions for the professional services were allowable deductions for the taxable year 1986. Hence, per Revenue Audit Memorandum Order No. 1-2000, they cannot be validly deducted from its gross income for the said year and were therefore properly disallowed by the BIR. As to the expenses for security services, the records show that these expenses were incurred by ICC in 198620 and could therefore be properly claimed as deductions for the said year. Anent the purported understatement of interest income from the promissory notes of Realty Investment, Inc., we sustain the findings of the CTA and the Court of Appeals that no such understatement exists and that only simple interest computation and not a compounded one should have been applied by the BIR. There is indeed no stipulation between the latter and ICC on the application of compounded interest. 21 Under Article 1959 of the Civil Code, unless there is a stipulation to the contrary, interest due should not further earn interest. Likewise, the findings of the CTA and the Court of Appeals that ICC truly withheld the required withholding tax from its claimed deductions for security services and remitted the same to the BIR is supported by payment order and confirmation receipts.22 Hence, the Assessment Notice for deficiency expanded withholding tax was properly cancelled and set aside. In sum, Assessment Notice No. FAS-1-86-90-000680 in the amount of P333,196.86 for deficiency income tax should be cancelled and set aside but only insofar as the claimed deductions of ICC for security services. Said Assessment is valid as to the BIR’s disallowance of ICC’s expenses for professional services. The Court of Appeal’s cancellation of Assessment Notice No. FAS-1-86-90-000681 in the amount of P4,897.79 for deficiency expanded withholding tax, is sustained. WHEREFORE, the petition is PARTIALLY GRANTED. The September 30, 2005 Decision of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 78426, is AFFIRMED with the MODIFICATION that Assessment Notice No. FAS1-86-90-000680, which disallowed the expense deduction of Isabela Cultural Corporation for professional and security services, is declared valid only insofar as the expenses for the professional fees of SGV & Co. and of the law firm, Bengzon Zarraga Narciso Cudala Pecson Azcuna & Bengson, are concerned. The decision is affirmed in all other respects. The case is remanded to the BIR for the computation of Isabela Cultural Corporation’s liability under Assessment Notice No. FAS-1-86-90-000680. SO ORDERED. G.R. No. 167679 July 22, 2015 ING BANK N.V., engaged in banking operations in the Philippines as ING BANK N.V. MANILA BRANCH, Petitioner, vs. COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE, Respondent. DECISION LEONEN, J.: Qualified taxpayers with pending tax cases may still avail themselves of the tax amnesty program under Republic Act No. 9480, otherwise known as the 2007 Tax Amnesty Act. Thus, the provision in BIR Revenue Memorandum Circular No. 19-2008 excepting "[i]ssues and cases which were ruled by any court (even without finality) in favor of the BIR prior to amnesty availment of the taxpayer" from the benefits of the law is illegal, invalid, and null and void. The duty to withhold the tax on compensation arises upon its accrual. 1 2 This is a Petition for Review appealing the April 5, 2005 Decision of the Court of Tax Appeals En Banc, which in turn affirmed the August 9, 2004 Decision and November 12, 2004 Resolution of the Court of Tax Appeals Second Division. The August 9, 2004 Decision held petitioner ING Bank, N.V. Manila Branch (ING Bank) liable for (a) deficiency documentary stamp tax for the taxable years 1996 and 1997 in the total amount of ₱238,545,052.38 inclusive of surcharges; (b) deficiency onshore tax for the taxable year 1996 in the total amount of ₱997,333.89 inclusive of surcharges and interest; and (c) deficiency withholding tax on compensation for the taxable years 1996 and 1997 in the total amount of ₱564,542.67 inclusive of interest. The Resolution denied ING Bank’s Motion for Reconsideration. 3 4 5 6 Deficiency on Compensation 1996 (ST-WC-96-0175-99) 1997 (ST-WC-97-0184-99) Deficiency Onshore Tax 1996 (ST-OT-96-0176-99) Deficiency Remittance Tax 1996 (ST-RT-96-0177-99) 1997 (ST-RT-97-0181-99) Deficiency Stamp Tax 1996 (ST-DST-96-0178-99 1997 (ST-DST-97-0181-99) 1997 (ST-DST-97-0180-99) Compromise Penalty 1996 (ST-CP-96-0179-99) 1997 (ST-CP-97-0186-99) Deficiency Final Tax 1997 (ST-FT-97-0183-99) TOTALS 8 9 ING Bank, "the Philippine branch of Internationale Nederlanden Bank N.V., a foreign banking corporation incorporated in the Netherlands[,] is duly authorized by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas to operate as a branch with full banking authority in the Philippines." 10 1,027,267.20 2,505,925.25 8,267,437.54 Tax 602,288.17 968,042.36 1,629,555.37 3,473,967.61 4,847,209.95 13,114,647.49 Profit 22,992,218[.]63 40,799,690.39 62,207,918.63 140,116,252.17 Documentary Branch 39,215,700.00 92,587,381.60 6,729,180.18 3,838,753.06 1,569,990.18 186,997,288.84 959,688.27 392,497.55 46,749,322.21 4,798,441.33 1,962,487.73 233,746,611.05 1,000.00 1,000.00 1,000.00 1,000.00 53,200.89 490,514,844.13 ============= 7 While this case was pending before this court, ING Bank filed a Manifestation and Motion stating that it availed itself of the government’s tax amnesty program under Republic Act No. 9480 with respect to its deficiency documentary stamp tax and deficiency onshore tax liabilities. What is at issue now is whether ING Bank is entitled to the immunities and privileges under Republic Act No. 9480,and whether the assessment for deficiency withholding tax on compensation is proper. Withholding 54,830,688.21 ============= 20,551.58 73,752.47 127,307,159.31 ============= 672,652,691.65 ============= On February 2, 2000, ING Bank "paid the deficiency assessments for [the] 1996 compromise penalty, 1997 deficiency documentary stamp tax and 1997 deficiency final tax in the respective amounts of ₱1,000.00, ₱1,000.00 and ₱75,013.25 [the original amount of ₱73,752.47 plus additional interest]." ING Bank, however, "protested [on the same day] the remaining ten (10) deficiency tax assessments in the total amount of ₱672,576,939.18." 16 17 ING Bank filed a Petition for Review before the Court of Tax Appeals on October 26, 2000. This case was docketed as C.T.A. Case No. 6187. The Petition was filed to seek "the cancellation and withdrawal of the deficiency tax assessments for the years 1996 and 1997, including the alleged deficiency documentary stamp tax on special savings accounts, deficiency onshore tax, and deficiency withholding tax on compensation mentioned above." 18 19 On January 3, 2000, ING Bank received a Final Assessment Notice dated December 3, 1999. The Final Assessment Notice also contained the Details of Assessment and 13 Assessment Notices "issued by the Enforcement Service of the Bureau of Internal Revenue through its Assistant Commissioner Percival T. Salazar[.]" The Final Assessment Notice covered the following deficiency tax assessments for taxable years 1996 and 1997: 11 12 13 14 After trial, the Court of Tax Appeals Second Division rendered its Decision on August 9, 2004, with the following disposition: 15 Particulars Deficiency Income Tax 1996 (ST-INC-96-0174-99) 1997 (ST-INC-97-0185-99) Basic Tax( ) 20,916,785.03 133,533,114.54 Surcharge( ) Interest( ) Total( ) 11,346,639.55 45,730,518.68 32,263,424.58 179,263,633.22 WHEREFORE, the assessments for 1996 and 1997 deficiency income tax, 1996 and 1997 deficiency branch profit remittance tax and 1997 deficiency documentary stamp tax on IBCLs exceeding five days are hereby CANCELLED and WITHDRAWN. However, the assessments for 1996 and 1997 deficiency withholding tax on compensation, 1996 deficiency onshore tax and 1996 and 1997 deficiency documentary stamp tax on special savings accounts are hereby UPHELD in the following amounts: Particulars Basic Tax Surcharge Revenue its Notice of Availment of Tax Amnesty Under Republic Act No. 9480 on December 14, 2007, together with the following documents: Interest Total P 61,445.11 109,362.26 P 167,384.97 397,157.70 (1) Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Net Worth (SALN) as of December 31, 2005 (original and amended declarations); 316,094.89 997,333.89 (2) Tax Amnesty Return For Taxable Year 2005 and Prior Years (BIR Form No. 2116); and (3) Tax Amnesty Payment Form (Acceptance of Payment Form) for Taxable Year 2005 and Prior Years (BIR Form No. 0617) showing payment of the amnesty tax in the amount of ₱500,000.00. P 486,902.26 4,798,441.33 233,746,611.05 ₱240,106,928.94 33 Deficiency Withholding Tax on Compensation 1996 (ST-WC-96-0175-99) P 105,939.86 1997 (ST-WC-97-0184-99) 287,795.44 Deficiency Onshore Tax 1996 (ST-OT-96-0176-99) 544,991.20 Deficiency Documentary Stamp Tax P 136,247.80 34 35 36 1996 (ST-DST-96-0178-99) 1997 (ST-DST-97-0180-99) TOTALS 3,838,753.06 186,997,288.84 ₱191,774,768.40 959,688.27 46,749,322.21 ₱47,845,258.28 Accordingly, petitioner is ORDERED to PAY the respondent the aggregate amount of ₱240,106,928.94, plus 20% delinquency interest per annum from February 3, 2000 until fully paid, pursuant to Section 249(C) of the National Internal Revenue Code of 1997. ING Bank prayed that this court issue a resolution taking note of its availment of the tax amnesty, and confirming its entitlement to all the immunities and privileges under Section 6 of Republic Act No. 9480, particularly with respect to the "payment of deficiency documentary stamp taxes on its special savings accounts for the taxable years 1996 and 1997 and deficiency tax on onshore interest income derived under the foreign currency deposit system for taxable year 1996[.]" 37 Pursuant to this court’s Resolution dated January 23, 2008, the Commissioner of Internal Revenue filed its Comment and ING Bank, its Reply. 38 39 SO ORDERED. (Emphasis in the original) 20 Both the Commissioner of Internal Revenue and ING Bank filed their respective Motions for Reconsideration. Both Motions were denied through the Second Division’s Resolution dated November 12, 2004, as follows: 40 Originally, ING Bank raised the following issues in its pleadings: 21 First, whether "[t]he Court of Tax Appeals En Banc erred in concluding that petitioner’s Special Saving Accounts are subject to documentary stamp tax (DST) as certificates of deposit under Section 180 of the 1977 Tax Code"; 41 WHEREFORE, the respondent’s Motion for Partial Reconsideration and the petitioner’s Motion for Reconsideration are hereby DENIED for lack of merit. The pronouncement reached in the assailed decision is REITERATED. SO ORDERED. Second, whether "[t]he Court of Tax Appeals En Banc erred in holding petitioner liable for deficiency onshore tax considering that under the 1977 Tax Code and the pertinent revenue regulations, the obligation to pay the ten percent (10%) final tax on onshore interest income rests on the payors-borrowers and not on petitioner as payee-lender"; and 42 22 On December 8, 2004, ING Bank filed its appeal before the Court of Tax Appeals En Banc. The Court of Tax Appeals En Banc denied due course to ING Bank’s Petition for Review and dismissed the same for lack of merit in the Decision promulgated on April 5, 2005. 23 24 Third, whether "[t]he Court of Tax Appeals En Banc erred in holding petitioner liable for deficiency withholding tax on compensation for the accrued bonuses in the taxable years 1996 and 1997 considering that these were not distributed to petitioner’s officers and employees during those taxable years, hence, were not yet subject to withholding tax." 43 Hence, ING Bank filed its Petition for Review before this court. The Commissioner of Internal Revenue filed its Comment on October 5, 2005 and ING Bank its Reply on December 14, 2005. Pursuant to this court’s Resolution dated January 25, 2006, the Commissioner of Internal Revenue filed its Manifestation and Motion on February 14, 2006, stating that it is adopting its Comment as its Memorandum, and ING Bank filed its Memorandum on March 9, 2006. 25 26 27 28 29 However, ING Bank availed itself of the tax amnesty under Republic Act No. 9480, with respect to its liabilities for deficiency documentary stamp taxes on its special savings accounts for the taxable years 1996 and 1997 and deficiency tax on onshore interest income under the foreign currency deposit system for taxable year 1996. 30 Consequently, the issues now for resolution are: On December 20, 2007, ING Bank filed a Manifestation and Motion informing this court that it had availed itself of the tax amnesty authorized and granted under Republic Act No. 9480 covering "all national internal revenue taxes for the taxable year 2005 and prior years, with or without assessments duly issued therefor, that have remained unpaid as of December 31, 2005[.]" ING Bank stated that it filed before the Bureau of Internal 31 32 First, whether petitioner ING Bank may validly avail itself of the tax amnesty granted by Republic Act No. 9480; and Second, whether petitioner ING Bank is liable for deficiency withholding tax on accrued bonuses for the taxable years 1996 and 1997. Tax amnesty availment upon such wages a tax," and BIR Ruling No. 555-88 (November 23, 1988) declaring that "[t]he withholding tax on the bonuses should be deducted upon the distribution of the same to the officers and employees[.]" Since the supposed bonuses were not distributed to the officers and employees in 1996 and 1997 but were distributed in the succeeding year when the amounts of the bonuses were finally determined, petitioner ING Bank asserts that its duty as employer to withhold the tax during these taxable years did not arise. 60 61 Petitioner ING Bank asserts that it is "qualified to avail of the tax amnesty under Section 5 [of Republic Act No. 9480] and . . . not disqualified under Section 8 [of the same law]." Respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue, for its part, does not deny the authenticity of the documents submitted by petitioner ING Bank or dispute the payment of the amnesty tax. However, respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue claims that petitioner ING Bank is not qualified to avail itself of the tax amnesty granted under Republic Act No. 9480 because both the Court of Tax Appeals En Banc and Second Division ruled in its favor that confirmed the liability of petitioner ING Bank for deficiency documentary stamp taxes, onshore taxes, and withholding taxes. 44 45 Respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue asserts that BIR Revenue Memorandum Circular No. 19-2008 specifically excludes "cases which were ruled by any court (even without finality) in favor of the BIR prior to amnesty availment of the taxpayer" from the coverage of the tax amnesty under Republic Act No. 9480. In any case, respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue argues that petitioner ING Bank’s availment of the tax amnesty is still subject to its evaluation, that it is "empowered to exercise [its] sound discretion . . . in the implementation of a tax amnesty in favor of a taxpayer," and "petitioner cannot presume that its application . . . would be granted[.]" Accordingly, respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue prays that "petitioner [ING Bank’s] motion be denied for lack of merit." 46 Petitioner ING Bank further argues that the Court of Tax Appeals’ discussion on Section 29(j) of the 1993 National Internal Revenue Code and Section 3 of Revenue Regulations No. 8-90 is not applicable because the issue in this case "is not whether the accrued bonuses should be allowed as deductions from petitioner’s taxable income but, rather, whether the accrued bonuses are subject to withholding tax on compensation in the respective years of accrual[.]" Respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue counters that petitioner ING Bank’s application of BIR Ruling No. 555-88 is misplaced because as found by the Second Division of the Court of Tax Appeals, the factual milieu is different: 62 63 In that ruling, bonuses are determined and distributed in the succeeding year "[A]fter [sic] the audit of each company is completed (on or before April 15 of the succeeding year)". The withholding and remittance of income taxes were also made in the year they were distributed to the employees. . . . 47 48 49 In petitioner’s case, bonuses were determined during the year but were distributed in the succeeding year. No withholding of income tax was effected but the bonuses were claimed as an expense for the year. . . . 50 Petitioner ING Bank counters that BIR Revenue Memorandum Circular No. 19-2008 cannot override Republic Act No. 9480 and its Implementing Rules and Regulations, which only exclude from tax amnesty "tax cases subject of final and [executory] judgment by the courts." Petitioner ING Bank asserts that its full compliance with the conditions prescribed in Republic Act No. 9480 (the conditions being submission of the requisite documents and payment of the amnesty tax), which respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue does not dispute, confirms that it is "qualified to avail itself, and has actually availed itself, of the tax amnesty." It argues that there is nothing in the law that gives respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue the discretion to rescind or erase the legal effects of its tax amnesty availment. Thus, the issue is no longer about whether "[it] is entitled to avail itself of the tax amnesty[,]" but rather whether the effects of its tax amnesty availment extend to the assessments of deficiency documentary stamp taxes on its special savings accounts for 1996 and 1997 and deficiency tax on onshore interest income for 1996. 51 52 53 Since the bonuses were not subjected to withholding tax during the year they were claimed as an expense, the same should be disallowed pursuant to the above-quoted law. 64 Respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue contends that petitioner ING Bank’s act of "claim[ing] [the] subject bonuses as deductible expenses in its taxable income although it has not yet withheld and remitted the [corresponding withholding] tax" to the Bureau of Internal Revenue contravened Section 29(j) of the 1997 National Internal Revenue Code, as amended. Respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue claims that "subject bonuses should also be disallowed as deductible expenses of petitioner." 65 66 67 54 I 55 Petitioner ING Bank points out the Court of Tax Appeals’ ruling in Metropolitan Bank and Trust Company v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, to the effect that full compliance with the requirements of the tax amnesty law extinguishes the tax deficiencies subject of the amnesty availment. Thus, with its availment of the tax amnesty and full compliance with all the conditions prescribed in the statute, petitioner ING Bank asserts that it is entitled to all the immunities and privileges under Section 6 of Republic Act No. 9480. Taxpayers with pending tax cases may avail themselves of the tax amnesty program under Republic Act No. 9480. 56 57 58 In CS Garment, Inc. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, this court has "definitively declare[d] . . . the exception ‘[i]ssues and cases which were ruled by any court (even without finality) in favor of the BIR prior to amnesty availment of the taxpayer’ under BIR [Revenue Memorandum Circular No.] 19-2008 [as] invalid, [for going] beyond the scope of the provisions of the 2007 Tax Amnesty Law." Thus: 68 69 Withholding tax on compensation Petitioner ING Bank claims that it is not liable for withholding taxes on bonuses accruing to its officers and employees during taxable years 1996 and 1997. It maintains its position that the liability of the employer to withhold the tax does not arise until such bonus is actually distributed. It cites Section 72 of the 1977 National Internal Revenue Code, which states that "[e]very employer making payment of wages shall deduct and withhold 59 [N]either the law nor the implementing rules state that a court ruling that has not attained finality would preclude the availment of the benefits of the Tax Amnesty Law. Both R.A. 9480 and DOF Order No. 29-07 are quite precise in declaring that "[t]ax cases subject of final and executory judgment by the courts" are the ones excepted from the benefits of the law. In fact, we have already pointed out the erroneous interpretation of the law in Philippine Banking Corporation (Now: Global Business Bank, Inc.) v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, viz: The BIR’s inclusion of "issues and cases which were ruled by any court (even without finality) in favor of the BIR prior to amnesty availment of the taxpayer" as one of the exceptions in RMC 19-2008 is misplaced. RA 9480 is specifically clear that the exceptions to the tax amnesty program include "tax cases subject of final and executory judgment by the courts." The present case has not become final and executory when Metrobank availed of the tax amnesty program. (Emphasis in the original, citation omitted) 70 Moreover, in the fairly recent case of LG Electronics Philippines, Inc. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, we confirmed that only cases that involve final and executory judgments are excluded from the tax amnesty program as explicitly provided under Section 8 of Republic Act No. 9480. 71 72 Thus, petitioner ING Bank is not disqualified from availing itself of the tax amnesty under the law during the pendency of its appeal before this court. II Petitioner ING Bank showed that it complied with the requirements set forth under Republic Act No. 9480. Respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue never questioned or rebutted that petitioner ING Bank fully complied with the requirements for tax amnesty under the law. Moreover, the contestability period of one (1) year from the time of petitioner ING Bank’s availment of the tax amnesty law on December 14, 2007 lapsed. Correspondingly, it is fully entitled to the immunities and privileges mentioned under Section 6 of Republic Act No. 9480. This is clear from the following provisions: SEC. 2. Availment of the Amnesty. - Any person, natural or juridical, who wishes to avail himself of the tax amnesty authorized and granted under this Act shall file with the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) a notice and Tax Amnesty Return accompanied by a Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Networth (SALN) as of December 31, 2005, in such form asmay be prescribed in the implementing rules and regulations (IRR) of this Act, and pay the applicable amnesty tax within six months from the effectivity of the IRR. a. The taxpayer shall be immune from the payment of taxes, as well as addition thereto, and the appurtenant civil, criminal or administrative penalties under the National Internal Revenue Code of 1997, as amended, arising from the failure to pay any and all internal revenue taxes for taxable year 2005 and prior years. b. The taxpayer’s Tax Amnesty Returns and the SALN as of December 31, 2005 shall not be admissible as evidence in all proceedings that pertain to taxable year 2005 and prior years, insofar as such proceedings relate to internal revenue taxes, before judicial, quasi-judicial or administrative bodies in which he is a defendant or respondent, and except for the purpose of ascertaining the networth beginning January 1, 2006, the same shall not be examined, inquired or looked into by any person or government office. However, the taxpayer may use this as a defense, whenever appropriate, in cases brought against him. c. The books of accounts and other records of the taxpayer for the years covered by the tax amnesty availed of shall not be examined: Provided, That the Commissioner of Internal Revenue may authorize in writing the examination of the said books of accounts and other records to verify the validity or correctness of a claim for any tax refund, tax credit (other than refund or credit of taxes withheld on wages), tax incentives, and/or exemptions under existing laws. (Emphasis supplied) Contrary to respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue’s stance, Republic Act No. 9480 confers no discretion on respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue. The provisions of the law are plain and simple. Unlike the power to compromise or abate a taxpayer’s liability under Section 204 of the 1997 National Internal Revenue Code that is within the discretion of respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue, its authority under Republic Act No. 9480 is limited to determining whether (a) the taxpayer is qualified to avail oneself of the tax amnesty; (b) all the requirements for availment under the law were complied with; and (c) the correct amount of amnesty tax was paid within the period prescribed by law. There is nothing in Republic Act No. 9480 which can be construed as authority for respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue to introduce exceptions and/or conditions to the coverage of the law nor to disregard its provisions and substitute his own personal judgment. 73 74 Republic Act No. 9480 provides a general grant of tax amnesty subject only to the cases specifically excepted by it. A tax amnesty "partakes of an absolute. . . waiver by the Government of its right to collect what otherwise would be due it[.]" The effect of a qualified taxpayer’s submission of the required documents and the payment of the prescribed amnesty tax was immunity from payment of all national internal revenue taxes as well as all administrative, civil, and criminal liabilities founded upon or arising from non-payment of national internal revenue taxes for taxable year 2005 and prior taxable years. 75 .... SEC. 4. Presumption of Correctness of the SALN. - The SALN as of December 31, 2005 shall be considered as true and correct except where the amount of declared networth is understated to the extent of thirty percent (30%) or more as may be established in proceedings initiated by, or at the instance of, parties other than the BIR or its agents: Provided, That such proceedings must be initiated within one year following the date of the filing of the tax amnesty return and the SALN. Findings of or admission in congressional hearings, other administrative agencies of government, and/or courts shall be admissible to prove a thirty percent (30%) underdeclaration. . . . . SEC. 6. Immunities and Privileges. - Those who availed themselves of the tax amnesty under Section 5 hereof, and have fully complied with all its conditions shall be entitled to the following immunities and privileges: 76 Finally, the documentary stamp tax and onshore income tax are covered by the tax amnesty program under Republic Act No. 9480 and its Implementing Rules and Regulations. Moreover, as to the deficiency tax on onshore interest income, it is worthy to state that petitioner ING Bank was assessed by respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue, not as a withholding agent, but as one that was directly liable for the tax on onshore interest income and failed to pay the same. 77 Considering petitioner ING Bank’s tax amnesty availment, there is no more issue regarding its liability for deficiency documentary stamp taxes on its special savings accounts for 1996 and 1997 and deficiency tax on onshore interest income for 1996, including surcharge and interest. III. The Court of Tax Appeals En Banc affirmed the factual finding of the Second Division that accrued bonuses were recorded in petitioner ING Bank’s books as expenses for taxable years 1996 and 1997, although no withholding of tax was effected: Consequently, petitioner is still liable for the amounts of ₱167,384.97 and ₱397,157.70 representing deficiency withholding taxes on compensation for the respective years of 1996 and 1997, computed as follows: With the preceding defense notwithstanding, petitioner now maintained that the portion of the disallowed bonuses in the amounts of ₱3,879,407.85 and ₱9,004,402.63 for the respective years 1996 and 1997, were actually payments for reimbursements of representation, travel and entertainment expenses of its officers. These expenses according to petitioner are not considered compensation of employees and likewise not subject to withholding tax. Total Disallowed Accrued Bonus 1996 1997 P 3,879,407.85 P 9,004,402.63 Less: Substantiated Reimbursement of Expense 3,479,332.84 7,970,283.92 In order to prove that the discrepancy in the accrued bonuses represents reimbursement of expenses, petitioner availed of the services of an independent CPA pursuant to CTA Circular No. 1-95, as amended. As a consequence, Mr. Ruben Rubio was commissioned by the court to verify the accuracy of petitioner’s position and to check its supporting documents. Unsubstantiated P 400,075.01 P 1,034,119.43 Tax Rate 26.48% 27.83% In a report dated January 29, 2002, the commissioned independent CPA noted the following pertinent findings: ... Basic Withholding Tax Due Thereon P 105,939.86 P 287,795.44 Interest (Sec. 249) 61,445.11 109,362.26 P 167,384.97 P 397,157.70 Findings and Observations Supporting document is under the name of the employee Supporting document is not under the name of the Bank nor its employees (addressee is "cash"/blank) Supporting document is under the name of the Bank Supporting document is in the name of another person (other than the employee claiming the expense) Supporting document is not dated within the period (i.e., 1996 and 1997) Date/year of transaction is not Indicated Amount is not supported by liquidation document(s) TOTAL 1997 P 930,307.56 537,456.37 1996 P 1,849,040.70 53,384.80 7,039,976.36 362,919.59 1,630,292.14 62,615.91 13,404.00 423,199.07 31,510.00 313,319.09 ₱9,228,892.97 26,126.49 935,044.28 ₱4,979,703.39 Deficiency Withholding Tax on Based on the above report, only the expenses in the name of petitioner’s employee and those under its name can be given credence. Therefore, the following expenses are valid expenses for income tax purposes: Compensation 78 An expense, whether the same is paid or payable, "shall be allowed as a deduction only if it is shown that the tax required to be deducted and withheld therefrom [was] paid to the Bureau of Internal Revenue[.]" 79 Section 29(j) of the 1977 National Internal Revenue Code (now Section 34(K) of the 1997 National Internal Revenue Code) provides: 80 Section 29. Deductions from gross income. — In computing taxable income subject to tax under Sec. 21(a); 24(a), (b) and (c); and 25(a) (1), there shall be allowed as deductions the items specified in paragraphs (a) to (i) of this section: . . . . .... Supporting document is under the name of the employee Supporting document is under the name of the Bank TOTAL 1996 ₱1,849,040.70 1,630,292.14 ₱3,479,332.84 1997 P 930,307.56 7,039,976.36 P 7,970,283.92 (a) Expenses. — (1) Business expenses. — (A) In general. — All ordinary and necessary expenses paid or incurred during the taxable year in carrying on any trade or business, including a reasonable allowance for salaries or other compensation for personal services actually rendered; travelling expenses while away from home in the pursuit of a trade, profession or business, rentals or other payments required to be made as a condition to the continued use or possession, for the purpose of the trade, profession or business, of property to which the taxpayer has not taken or is not taking title or in which he has no equity. .... It is true that the law and implementing regulations require the employer to deduct and pay the income tax on compensation paid to its employees, either actually or constructively. (j) Additional requirement for deductibility of certain payments. — Any amount paid or payable which is otherwise deductible from, or taken into account in computing gross income for which depreciation or amortization may be allowed under this section, shall be allowed as a deduction only if it is shown that the tax required to be deducted and withheld therefrom has been paid to the Bureau of Internal Revenue in accordance with this section, Sections 51 and 74 of this Code. (Emphasis supplied) 81 82 Section 72 of the 1977 National Internal Revenue Code, as amended, states: 91 SECTION 72. Income tax collected at source. — (a) Requirement of withholding. — Every employer making payment of wages shall deduct and withhold upon such wages a tax determined in accordance with regulations to be prepared and promulgated by the Minister of Finance. (Emphasis supplied) Section 3 of Revenue Regulations No. 8-90 (now Section 2.58.5 of Revenue Regulations No. 2-98) provides: Section 3. Section 9 of Revenue Regulations No. 6-85 is hereby amended to read as follows: Sections 7 and 14 of Revenue Regulations No. 6-82, as amended, relative to the withholding of tax on compensation income, provide: Section 9. (a) Requirement for deductibility. Any income payment, which is otherwise deductible under Sections 29 and 54 of the Tax Code, as amended, shall be allowed as a deduction from the payor’s gross income only if it is shown that the tax required to be withheld has been paid to the Bureau of Internal Revenue in accordance with Sections 50, 51, 72, and 74 also of the Tax Code.(Emphasis supplied) Section 7. Requirement of withholding.— Every employer or any person who pays or controls the payment of compensation to an employee, whether resident citizen or alien, non-resident citizen, or nonresident alien engaged in trade or business in the Philippines, must withhold from such compensation paid, an amount computed in accordance with these regulations. Under the National Internal Revenue Code, every form of compensation for personal services is subject to income tax and, consequently, to withholding tax. The term "compensation" means all remunerations paid for services performed by an employee for his or her employer, whether paid in cash or in kind, unless specifically excluded under Sections 32(B) and 78(A) of the 1997 National Internal Revenue Code. The name designated to the remuneration for services is immaterial. Thus, "salaries, wages, emoluments and honoraria, bonuses, allowances (such as transportation, representation, entertainment, and the like), [taxable] fringe benefits[,] pensions and retirement pay, and other income of a similar nature constitute compensation income" that is taxable. I. Withholding of tax on compensation paid to resident employees. – (a)In general, every employer making payment of compensation shall deduct and withhold from such compensation income for the entire calendar year, a tax determined in accordance with the prescribed new Withholding Tax Tables effective January 1, 1992 (ANNEX "A"). 92 83 84 85 93 .... 86 Hence, petitioner ING Bank is liable for the withholding tax on the bonuses since it claimed the same as expenses in the year they were accrued. Petitioner ING Bank insists, however, that the bonus accruals in 1996 and 1997 were not yet subject to withholding tax because these bonuses were actually distributed only in the succeeding years of their accrual (i.e., in 1997 and 1998) when the amounts were finally determined. Petitioner ING Bank’s contention is untenable. The tax on compensation income is withheld at source under the creditable withholding tax system wherein the tax withheld is intended to equal or at least approximate the tax due of the payee on the said income. It was designed to enable (a) the individual taxpayer to meet his or her income tax liability on compensation earned; and (b) the government to collect at source the appropriate taxes on compensation. Taxes withheld are creditable in nature. Thus, the employee is still required to file an income tax return to report the income and/or pay the difference between the tax withheld and the tax due on the income. For over withholding, the employee is refunded. Therefore, absolute or exact accuracy in the determination of the amount of the compensation income is not a prerequisite for the employer’s withholding obligation to arise. 87 88 Section 14. Liability for the Tax.— The employer is required to collect the tax by deducting and withholding the amount thereof from the employee’s compensation as when paid, either actually or constructively. An employer is required to deduct and withhold the tax notwithstanding that the compensation is paid in something other than money (for example, compensation paid in stocks or bonds) and to pay the tax to the collecting officer. If compensation is paid in property other than money, the employer should make necessary arrangements to ensure that the amount of the tax required to be withheld is available for payment to the collecting officer. Every person required to deduct and withhold the tax from the compensation of an employee is liable for the payment of such tax whether or not collected from the employee. If, for example, the employer deducts less than the correct amount of tax, or if he fails to deduct any part of the tax, he is nevertheless liable for the correct amount of the tax. However, if the employer in violation of the provisions of Chapter XI, Title II of the Tax Code fails to deduct and withhold and thereafter the employee pays the tax, it shall no longer be collected from the employer. Such payment does not, however, operate to relieve the employer from liability for penalties or additions to the tax for failure to deduct and withhold within the time prescribed by law or regulations. The employer will not be relieved of his liability for payment of the tax required to be withheld unless he can show that the tax has been paid by the employee. 89 90 The amount of any tax withheld/collected by the employer is a special fund in trust for the Government of the Philippines. When the employer or other person required to deduct and withhold the tax under this Chapter XI, Title II of the Tax Code has withheld and paid such tax to the Commissioner of Internal Revenue or to any authorized collecting officer, then such employer or person shall be relieved of any liability to any person. (Emphasis supplied) Constructive payment of compensation is further defined in Revenue Regulations No. 6-82: The all-events test requires the right to income or liability be fixed, and the amount of such income or liability be determined with reasonable accuracy. However, the test does not demand that the amount of income or liability be known absolutely, only that a taxpayer has at his disposal the information necessary to compute the amount with reasonable accuracy. The all-events test is satisfied where computation remains uncertain, if its basis is unchangeable; the test is satisfied where a computation may be unknown, but is not as much as unknowable, within the taxable year. The amount of liability does not have to be determined exactly; it must be determined with "reasonable accuracy. "Accordingly, the term "reasonable accuracy" implies something less than anex act or completely accurate amount. (Emphasis supplied, citations omitted) 1âw phi 1 95 Section 25. Applicability; constructive receipt of compensation. —.... Compensation is constructively paid within the meaning of these regulations when it is credited to the account of or set apart for an employee so that it may be drawn upon by him at any time although not then actually reduced to possession. To constitute payment in such a case, the compensation must be credited or set apart for the employee without any substantial limitation or restriction as to the time or manner of payment or condition upon which payment is to be made, and must be made available to him so that it may be drawn upon at any time, and its payment brought within his control and disposition. (Emphasis supplied) Thus, if the taxpayer is on cash basis, he expense is deductible in the year it was paid, regardless of the year it was incurred. If he is on the accrual method, he can deduct the expense upon accrual thereof. An item that is reasonably ascertained as to amount and acknowledged to be due has "accrued"; actual payment is not essential to constitute "expense." Stated otherwise, an expense is accrued and deducted for tax purposes when (1) the obligation to pay is already fixed; (2) the amount can be determined with reasonable accuracy; and (3) it is already knowable or the taxpayer can reasonably be expected to have known at the closing of its books for the taxable year. Section 29(j) of the 1977 National Internal Revenue Code (Section 34(K) of the 1997 National Internal Revenue Code) expressly requires, as a condition for deductibility of an expense, that the tax required to be withheld on the amount paid or payable is shown to have been remitted to the Bureau of Internal Revenue by the taxpayer constituted as a withholding agent of the government. 96 On the other hand, it is also true that under Section 45 of the 1997 National Internal Revenue Code (then Section 39 of the 1977 National Internal Revenue Code, as amended), deductions from gross income are taken for the taxable year in which "paid or accrued" or "paid or incurred" is dependent upon the method of accounting income and expenses adopted by the taxpayer. In Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Isabela Cultural Corporation, this court explained the accrual method of accounting, as against the cash method: 94 Accounting methods for tax purposes comprise a set of rules for determining when and how to report income and deductions. . . . The provision of Section 72 of the 1977 National Internal Revenue Code (Section 79 of the 1997 National Internal Revenue Code) regarding withholding on wages must be read and construed in harmony with Section 29(j) of the 1977 National Internal Revenue Code (Section 34(K) of the 1997 National Internal Revenue Code) on deductions from gross income. This is in accordance with the rule on statutory construction that an interpretation is to be sought which gives effect to the whole of the statute, such that every part is made effective, harmonious, and sensible, if possible, and not defeated nor rendered insignificant, meaningless, and nugatory. If we go by the theory of petitioner ING Bank, then the condition imposed by Section 29(j) would have been rendered nugatory, or we would in effect have created an exception to this mandatory requirement when there was none in the law. 97 98 Revenue Audit Memorandum Order No. 1-2000, provides that under the accrual method of accounting, expenses not being claimed as deductions by a taxpayer in the current year when they are incurred cannot be claimed as deduction from income for the succeeding year. Thus, a taxpayer who is authorized to deduct certain expenses and other allowable deductions for the current year but failed to do so cannot deduct the same for the next year. The accrual method relies upon the taxpayer’s right to receive amounts or its obligation to pay them, in opposition to actual receipt or payment, which characterizes the cash method of accounting. Amounts of income accrue where the right to receive them become fixed, where there is created an enforceable liability. Similarly, liabilities are accrued when fixed and determinable in amount, without regard to indeterminacy merely of time of payment. Reading together the two provisions, we hold that the obligation of the payor/employer to deduct and withhold the related withholding tax arises at the time the income was paid or accrued or recorded as an expense in the payor’s/employer’s books, whichever comes first. Petitioner ING Bank accrued or recorded the bonuses as deductible expense in its books. Therefore, its obligation to withhold the related withholding tax due from the deductions for accrued bonuses arose at the time of accrual and not at the time of actual payment. In Filipinas Synthetic Fiber Corporation v. Court of Appeals, the issue was raised on "whether the liability to withhold tax at source on income payments to non-resident foreign corporations arises upon remittance of the amounts due to the foreign creditors or upon accrual thereof." In resolving this issue, this court considered the nature of the accounting method employed by the withholding agent, which was the accrual method, wherein it was the right to receive income, and not the actual receipt, that determined when to report the amount as part 99 For a taxpayer using the accrual method, the determinative question is, when do the facts present themselves in such a manner that the taxpayer must recognize income or expense? The accrual of income and expense is permitted when the all-events test has been met. This test requires: (1) fixing of a right to income or liability to pay; and (2) the availability of the reasonable accurate determination of such income or liability. 100 of the taxpayer’s gross income. It upheld the lower court’s finding that there was already a definite liability on the part of petitioner at the maturity of the loan contracts. Moreover, petitioner already deducted as business expense the said amounts as interests due to the foreign corporation. Consequently, the taxpayer could not claim that there was "no duty to withhold and remit income taxes as yet because the loan contract was not yet due and demandable." Petitioner, "[h]aving ‘written-off’ the amounts as business expense in its books, . . . had taken advantage of the benefit provided in the law allowing for deductions from gross income." 101 102 103 104 105 Here, petitioner ING Bank already recognized a definite liability on its part considering that it had deducted as business expense from its gross income the accrued bonuses due to its employees. Underlying its accrual of the bonus expense was a reasonable expectation or probability that the bonus would be achieved. In this sense, there was already a constructive payment for income tax purposes as these accrued bonuses were already allotted or made available to its officers and employees. We note petitioner ING Bank's earlier claim before the Court of Tax Appeals that the bonus accruals in 1996 and 1997 were disbursed in the following year of accrual, as reimbursements of representation, travel, and entertainment expenses incurred by its employees. This shows that the accrued bonuses in the amounts of ₱400,075.0l (1996) and Pl,034,119.43 (1997) on which deficiency withholding taxes of Pl67,384.97 (1996) and ₱397,157.70 (1997) were imposed, respectively, were already set apart or made available to petitioner ING Bank's officers and employees. To avoid any tax issue, petitioner ING Bank should likewise have recognized the withholding tax liabilities associated with the bonuses at the time of accrual. 106 WHEREFORE, the Petition is PARTLY GRANTED. The assessments with respect to petitioner ING Bank's liabilities for deficiency documentary stamp taxes on its special savings accounts for the taxable years 1996 and 1997 and deficiency tax on onshore interest income under the foreign currency deposit system for taxable year 1996 are hereby SET ASIDE solely in view of petitioner ING Bank's availment of the tax amnesty program under Republic Act No. 9480. The April 5, 2005 Decision of the Court of Tax Appeals En Banc, which affirmed the August 9, 2004 Decision and November 12, 2004 Resolution of the Court of Tax Appeals Second Division holding petitioner ING Bank liable for deficiency withholding tax on compensation for the taxable years 1996 and 1997 in the total amount of ₱564,542.67 inclusive of interest, is AFFIRMED. SO ORDERED. SEC. 37. Income from sources within the Philippines. — (a) Gross income from sources within the Philippines. — The following items of gross income shall be treated as gross income from sources within the Philippines: (1) Interest. — Interest derived from sources within the Philippines, and interest on bonds, notes, or other interest-bearing obligations of residents, corporate or otherwise; xxx G.R. No. L-53961 June 30, 1987 NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT REVENUE, respondent. COMPANY, petitioner, vs. COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL xxx xxx The petitioner argues that the Japanese shipbuilders were not subject to tax under the above provision because all the related activities — the signing of the contract, the construction of the vessels, the payment of the stipulated price, and their delivery to the NDC — were done in Tokyo. The law, however, does not speak of activity but of "source," which in this case is the NDC. This is a domestic and resident corporation with principal offices in Manila. 8 CRUZ, J.: As the Tax Court put it: We are asked to reverse the decision of the Court of Tax Appeals on the ground that it is erroneous. We have carefully studied it and find it is not; on the contrary, it is supported by law and doctrine. So finding, we affirm. Reduced to simplest terms, the background facts are as follows. The national Development Company entered into contracts in Tokyo with several Japanese shipbuilding companies for the construction of twelve ocean-going vessels. The purchase price was to come from the proceeds of bonds issued by the Central Bank. Initial payments were made in cash and through irrevocable letters of credit. Fourteen promissory notes were signed for the balance by the NDC and, as required by the shipbuilders, guaranteed by the Republic of the Philippines. Pursuant thereto, the remaining payments and the interests thereon were remitted in due time by the NDC to Tokyo. The vessels were eventually completed and delivered to the NDC in Tokyo. 1 2 3 4 5 The NDC remitted to the shipbuilders in Tokyo the total amount of US$4,066,580.70 as interest on the balance of the purchase price. No tax was withheld. The Commissioner then held the NDC liable on such tax in the total sum of P5,115,234.74. Negotiations followed but failed. The BIR thereupon served on the NDC a warrant of distraint and levy to enforce collection of the claimed amount. The NDC went to the Court of Tax Appeals. 6 The BIR was sustained by the CTA except for a slight reduction of the tax deficiency in the sum of P900.00, representing the compromise penalty. The NDC then came to this Court in a petition for certiorari. 7 The petition must fail for the following reasons. The Japanese shipbuilders were liable to tax on the interest remitted to them under Section 37 of the Tax Code, thus: It is quite apparent, under the terms of the law, that the Government's right to levy and collect income tax on interest received by foreign corporations not engaged in trade or business within the Philippines is not planted upon the condition that 'the activity or labor — and the sale from which the (interest) income flowed had its situs' in the Philippines. The law specifies: 'Interest derived from sources within the Philippines, and interest on bonds, notes, or other interest-bearing obligations of residents, corporate or otherwise.' Nothing there speaks of the 'act or activity' of non-resident corporations in the Philippines, or place where the contract is signed. The residence of the obligor who pays the interest rather than the physical location of the securities, bonds or notes or the place of payment, is the determining factor of the source of interest income. (Mertens, Law of Federal Income Taxation, Vol. 8, p. 128, citing A.C. Monk & Co. Inc. 10 T.C. 77; Sumitomo Bank, Ltd., 19 BTA 480; Estate of L.E. Mckinnon, 6 BTA 412; Standard Marine Ins. Co., Ltd., 4 BTA 853; Marine Ins. Co., Ltd., 4 BTA 867.) Accordingly, if the obligor is a resident of the Philippines the interest payment paid by him can have no other source than within the Philippines. The interest is paid not by the bond, note or other interestbearing obligations, but by the obligor. (See mertens, Id., Vol. 8, p. 124.) Here in the case at bar, petitioner National Development Company, a corporation duly organized and existing under the laws of the Republic of the Philippines, with address and principal office at Calle Pureza, Sta. Mesa, Manila, Philippines unconditionally promised to pay the Japanese shipbuilders, as obligor in fourteen (14) promissory notes for each vessel, the balance of the contract price of the twelve (12) ocean-going vessels purchased and acquired by it from the Japanese corporations, including the interest on the principal sum at the rate of five per cent (5%) per annum. (See Exhs. "D", D-1" to "D13", pp. 100-113, CTA Records; par. 11, Partial Stipulation of Facts.) And pursuant to the terms and conditions of these promisory notes, which are duly signed by its Vice Chairman and General Manager, petitioner remitted to the Japanese shipbuilders in Japan during the years 1960, 1961, and 1962 the sum of $830,613.17, $1,654,936.52 and $1,541.031.00, respectively, as interest on the unpaid balance of the purchase price of the aforesaid vessels. (pars. 13, 14, & 15, Partial Stipulation of Facts.) The law is clear. Our plain duty is to apply it as written. The residence of the obligor which paid the interest under consideration, petitioner herein, is Calle Pureza, Sta. Mesa, Manila, Philippines; and as a corporation duly organized and existing under the laws of the Philippines, it is a domestic corporation, resident of the Philippines. (Sec. 84(c), National Internal Revenue Code.) The interest paid by petitioner, which is admittedly a resident of the Philippines, is on the promissory notes issued by it. Clearly, therefore, the interest remitted to the Japanese shipbuilders in Japan in 1960, 1961 and 1962 on the unpaid balance of the purchase price of the vessels acquired by petitioner is interest derived from sources within the Philippines subject to income tax under the then Section 24(b)(1) of the National Internal Revenue Code. 9 There is no basis for saying that the interest payments were obligations of the Republic of the Philippines and that the promissory notes of the NDC were government securities exempt from taxation under Section 29(b)[4] of the Tax Code, reading as follows: SEC. 29. Gross Income. — xxxx xxx xxx xxx (b) Exclusion from gross income. — The following items shall not be included in gross income and shall be exempt from taxation under this Title: xxx xxx xxx Sec. 53(b). Nonresident aliens. — All persons, corporations and general co-partnership (companies colectivas), in whatever capacity acting, including lessees or mortgagors of real or personal capacity, executors, administrators, receivers, conservators, fiduciaries, employers, and all officers and employees of the Government of the Philippines having control, receipt, custody; disposal or payment of interest, dividends, rents, salaries, wages, premiums, annuities, compensations, remunerations, emoluments, or other fixed or determinable annual or categorical gains, profits and income of any nonresident alien individual, not engaged in trade or business within the Philippines and not having any office or place of business therein, shall (except in the cases provided for in subsection (a) of this section) deduct and withhold from such annual or periodical gains, profits and income a tax to twenty (now 30%) per centum thereof: ... Sec. 54. Payment of corporation income tax at source. — In the case of foreign corporations subject to taxation under this Title not engaged in trade or business within the Philippines and not having any office or place of business therein, there shall be deducted and withheld at the source in the same manner and upon the same items as is provided in section fifty-three a tax equal to thirty (now 35%) per centum thereof, and such tax shall be returned and paid in the same manner and subject to the same conditions as provided in that section:.... Manifestly, the said undertaking of the Republic of the Philippines merely guaranteed the obligations of the NDC but without diminution of its taxing power under existing laws. (4) Interest on Government Securities. — Interest upon the obligations of the Government of the Republic of the Philippines or any political subdivision thereof, but in the case of such obligations issued after approval of this Code, only to the extent provided in the act authorizing the issue thereof. (As amended by Section 6, R.A. No. 82; emphasis supplied) In suggesting that the NDC is merely an administrator of the funds of the Republic of the Philippines, the petitioner closes its eyes to the nature of this entity as a corporation. As such, it is governed in its proprietary activities not only by its charter but also by the Corporation Code and other pertinent laws. The law invoked by the petitioner as authorizing the issuance of securities is R.A. No. 1407, which in fact is silent on this matter. C.A. No. 182 as amended by C.A. No. 311 does carry such authorization but, like R.A. No. 1407, does not exempt from taxes the interests on such securities. The petitioner also forgets that it is not the NDC that is being taxed. The tax was due on the interests earned by the Japanese shipbuilders. It was the income of these companies and not the Republic of the Philippines that was subject to the tax the NDC did not withhold. It is also incorrect to suggest that the Republic of the Philippines could not collect taxes on the interest remitted because of the undertaking signed by the Secretary of Finance in each of the promissory notes that: In effect, therefore, the imposition of the deficiency taxes on the NDC is a penalty for its failure to withhold the same from the Japanese shipbuilders. Such liability is imposed by Section 53(c) of the Tax Code, thus: Upon authority of the President of the Republic of the Philippines, the undersigned, for value received, hereby absolutely and unconditionally guarantee (sic), on behalf of the Republic of the Philippines, the due and punctual payment of both principal and interest of the above note. Section 53(c). Return and Payment. — Every person required to deduct and withhold any tax under this section shall make return thereof, in duplicate, on or before the fifteenth day of April of each year, and, on or before the time fixed by law for the payment of the tax, shall pay the amount withheld to the officer of the Government of the Philippines authorized to receive it. Every such person is made personally liable for such tax, and is indemnified against the claims and demands of any person for the amount of any payments made in accordance with the provisions of this section. (As amended by Section 9, R.A. No. 2343.) 10 There is nothing in the above undertaking exempting the interests from taxes. Petitioner has not established a clear waiver therein of the right to tax interests. Tax exemptions cannot be merely implied but must be categorically and unmistakably expressed. Any doubt concerning this question must be resolved in favor of the taxing power. 11 12 In Philippine Guaranty Co. v. The Commissioner of Internal Revenue and the Court of Tax Appeals, the Court quoted with approval the following regulation of the BIR on the responsibilities of withholding agents: 13 Nowhere in the said undertaking do we find any inhibition against the collection of the disputed taxes. In fact, such undertaking was made by the government in consonance with and certainly not against the following provisions of the Tax Code: In case of doubt, a withholding agent may always protect himself by withholding the tax due, and promptly causing a query to be addressed to the Commissioner of Internal Revenue for the determination whether or not the income paid to an individual is not subject to withholding. In case the Commissioner of Internal Revenue decides that the income paid to an individual is not subject to withholding, the withholding agent may thereupon remit the amount of a tax withheld. (2nd par., Sec. 200, Income Tax Regulations). "Strict observance of said steps is required of a withholding agent before he could be released from liability," so said Justice Jose P. Bengson, who wrote the decision. "Generally, the law frowns upon exemption from taxation; hence, an exempting provision should be construed strictissimi juris." 14 The petitioner was remiss in the discharge of its obligation as the withholding agent of the government an so should be held liable for its omission. WHEREFORE, the appealed decision is AFFIRMED, without any pronouncement as to costs. It is so ordered. G.R. No. 153793 August 29, 2006 COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE, Petitioner, vs. JULIANE BAIER-NICKEL, as represented by Marina Q. Guzman (Attorney-in-fact) Respondent. DECISION YNARES-SANTIAGO, J.: Petitioner Commissioner of Internal Revenue (CIR) appeals from the January 18, 2002 Decision 1 of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 59794, which granted the tax refund of respondent Juliane Baier-Nickel and reversed the June 28, 2000 Decision2 of the Court of Tax Appeals (CTA) in C.T.A. Case No. 5633. Petitioner also assails the May 8, 2002 Resolution3 of the Court of Appeals denying its motion for reconsideration. The facts show that respondent Juliane Baier-Nickel, a non-resident German citizen, is the President of JUBANITEX, Inc., a domestic corporation engaged in "[m]anufacturing, marketing on wholesale only, buying or otherwise acquiring, holding, importing and exporting, selling and disposing embroidered textile products."4 Through JUBANITEX’s General Manager, Marina Q. Guzman, the corporation appointed and engaged the services of respondent as commission agent. It was agreed that respondent will receive 10% sales commission on all sales actually concluded and collected through her efforts.5 In 1995, respondent received the amount of P1,707,772.64, representing her sales commission income from which JUBANITEX withheld the corresponding 10% withholding tax amounting to P170,777.26, and remitted the same to the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR). On October 17, 1997, respondent filed her 1995 income tax return reporting a taxable income of P1,707,772.64 and a tax due of P170,777.26. 6 The next day, April 15, 1998, she filed a petition for review with the CTA contending that no action was taken by the BIR on her claim for refund.7 On June 28, 2000, the CTA rendered a decision denying her claim. It held that the commissions received by respondent were actually her remuneration in the performance of her duties as President of JUBANITEX and not as a mere sales agent thereof. The income derived by respondent is therefore an income taxable in the Philippines because JUBANITEX is a domestic corporation. On petition with the Court of Appeals, the latter reversed the Decision of the CTA, holding that respondent received the commissions as sales agent of JUBANITEX and not as President thereof. And since the "source" of income means the activity or service that produce the income, the sales commission received by respondent is not taxable in the Philippines because it arose from the marketing activities performed by respondent in Germany. The dispositive portion of the appellate court’s Decision, reads: WHEREFORE, premises considered, the assailed decision of the Court of Tax Appeals dated June 28, 2000 is hereby REVERSED and SET ASIDE and the respondent court is hereby directed to grant petitioner a tax refund in the amount of Php 170,777.26. SO ORDERED.8 Petitioner filed a motion for reconsideration but was denied. 9 Hence, the instant recourse. Petitioner maintains that the income earned by respondent is taxable in the Philippines because the source thereof is JUBANITEX, a domestic corporation located in the City of Makati. It thus implied that source of income means the physical source where the income came from. It further argued that since respondent is the President of JUBANITEX, any remuneration she received from said corporation should be construed as payment of her overall managerial services to the company and should not be interpreted as a compensation for a distinct and separate service as a sales commission agent. Respondent, on the other hand, claims that the income she received was payment for her marketing services. She contended that income of nonresident aliens like her is subject to tax only if the source of the income is within the Philippines. Source, according to respondent is the situs of the activity which produced the income. And since the source of her income were her marketing activities in Germany, the income she derived from said activities is not subject to Philippine income taxation. The issue here is whether respondent’s sales commission income is taxable in the Philippines. Pertinent portion of the National Internal Revenue Code (NIRC), states: SEC. 25. Tax on Nonresident Alien Individual. – (A) Nonresident Alien Engaged in Trade or Business Within the Philippines. – On April 14, 1998, respondent filed a claim to refund the amount of P170,777.26 alleged to have been mistakenly withheld and remitted by JUBANITEX to the BIR. Respondent contended that her sales commission income is not taxable in the Philippines because the same was a compensation for her services rendered in Germany and therefore considered as income from sources outside the Philippines. (1) In General. – A nonresident alien individual engaged in trade or business in the Philippines shall be subject to an income tax in the same manner as an individual citizen and a resident alien individual, on taxable income received from all sources within the Philippines. A nonresident alien individual who shall come to the Philippines and stay therein for an aggregate period of more than one hundred eighty (180) days during any calendar year shall be deemed a ‘nonresident alien doing business in the Philippines,’ Section 22(G) of this Code notwithstanding. xxxx xxxx xxxx (B) Nonresident Alien Individual Not Engaged in Trade or Business Within the Philippines. – There shall be levied, collected and paid for each taxable year upon the entire income received from all sources within the Philippines by every nonresident alien individual not engaged in trade or business within the Philippines x x x a tax equal to twenty-five percent (25%) of such income. x x x Pursuant to the foregoing provisions of the NIRC, non-resident aliens, whether or not engaged in trade or business, are subject to Philippine income taxation on their income received from all sources within the Philippines. Thus, the keyword in determining the taxability of non-resident aliens is the income’s "source." In construing the meaning of "source" in Section 25 of the NIRC, resort must be had on the origin of the provision. The first Philippine income tax law enacted by the Philippine Legislature was Act No. 2833, 10 which took effect on January 1, 1920.11 Under Section 1 thereof, nonresident aliens are likewise subject to tax on income "from all sources within the Philippine Islands," thus – SECTION 1. (a) There shall be levied, assessed, collected, and paid annually upon the entire net income received in the preceding calendar year from all sources by every individual, a citizen or resident of the Philippine Islands, a tax of two per centum upon such income; and a like tax shall be levied, assessed, collected, and paid annually upon the entire net income received in the preceding calendar year from all sources within the Philippine Islands by every individual, a nonresident alien, including interest on bonds, notes, or other interestbearing obligations of residents, corporate or otherwise. Act No. 2833 substantially reproduced the United States (U.S.) Revenue Law of 1916 as amended by U.S. Revenue Law of 1917.12 Being a law of American origin, the authoritative decisions of the official charged with enforcing it in the U.S. have peculiar persuasive force in the Philippines. 13 The Internal Revenue Code of the U.S. enumerates specific types of income to be treated as from sources within the U.S. and specifies when similar types of income are to be treated as from sources outside the U.S.14 Under the said Code, compensation for labor and personal services performed in the U.S., is generally treated as income from U.S. sources; while compensation for said services performed outside the U.S., is treated as income from sources outside the U.S.15 A similar provision is found in Section 42 of our NIRC, thus: SEC. 42. x x x (A) Gross Income From Sources Within the Philippines. x x x xxxx (3) Services. – Compensation for labor or personal services performed in the Philippines; (C) Gross Income From Sources Without the Philippines. x x x (3) Compensation for labor or personal services performed without the Philippines; The following discussions on sourcing of income under the Internal Revenue Code of the U.S., are instructive: The Supreme Court has said, in a definition much quoted but often debated, that income may be derived from three possible sources only: (1) capital and/or (2) labor; and/or (3) the sale of capital assets. While the three elements of this attempt at definition need not be accepted as all-inclusive, they serve as useful guides in any inquiry into whether a particular item is from "sources within the United States" and suggest an investigation into the nature and location of the activities or property which produce the income. If the income is from labor the place where the labor is done should be decisive; if it is done in this country, the income should be from "sources within the United States." If the income is from capital, the place where the capital is employed should be decisive; if it is employed in this country, the income should be from "sources within the United States." If the income is from the sale of capital assets, the place where the sale is made should be likewise decisive. Much confusion will be avoided by regarding the term "source" in this fundamental light. It is not a place, it is an activity or property. As such, it has a situs or location, and if that situs or location is within the United States the resulting income is taxable to nonresident aliens and foreign corporations. The intention of Congress in the 1916 and subsequent statutes was to discard the 1909 and 1913 basis of taxing nonresident aliens and foreign corporations and to make the test of taxability the "source," or situs of the activities or property which produce the income. The result is that, on the one hand, nonresident aliens and nonresident foreign corporations are prevented from deriving income from the United States free from tax, and, on the other hand, there is no undue imposition of a tax when the activities do not take place in, and the property producing income is not employed in, this country. Thus, if income is to be taxed, the recipient thereof must be resident within the jurisdiction, or the property or activities out of which the income issues or is derived must be situated within the jurisdiction so that the source of the income may be said to have a situs in this country. The underlying theory is that the consideration for taxation is protection of life and property and that the income rightly to be levied upon to defray the burdens of the United States Government is that income which is created by activities and property protected by this Government or obtained by persons enjoying that protection. 16 The important factor therefore which determines the source of income of personal services is not the residence of the payor, or the place where the contract for service is entered into, or the place of payment, but the place where the services were actually rendered.17 In Alexander Howden & Co., Ltd. v. Collector of Internal Revenue, 18 the Court addressed the issue on the applicable source rule relating to reinsurance premiums paid by a local insurance company to a foreign insurance company in respect of risks located in the Philippines. It was held therein that the undertaking of the foreign insurance company to indemnify the local insurance company is the activity that produced the income. Since the activity took place in the Philippines, the income derived therefrom is taxable in our jurisdiction. Citing Mertens, The Law of Federal Income Taxation, the Court emphasized that the technical meaning of source of income is the property, activity or service that produced the same. Thus: of the functions which are normally incident to, and are in progressive pursuit of, the purpose and object of its organization as an international air carrier. In fact, the regular sale of tickets, its main activity, is the very lifeblood of the airline business, the generation of sales being the paramount objective. There should be no doubt then that BOAC was "engaged in" business in the Philippines through a local agent during the period covered by the assessments. x x x21 The source of an income is the property, activity or service that produced the income. The reinsurance premiums remitted to appellants by virtue of the reinsurance contracts, accordingly, had for their source the undertaking to indemnify Commonwealth Insurance Co. against liability. Said undertaking is the activity that produced the reinsurance premiums, and the same took place in the Philippines. x x x the reinsured, the liabilities insured and the risk originally underwritten by Commonwealth Insurance Co., upon which the reinsurance premiums and indemnity were based, were all situated in the Philippines. x x x19 The source of an income is the property, activity or service that produced the income. For the source of income to be considered as coming from the Philippines, it is sufficient that the income is derived from activity within the Philippines. In BOAC's case, the sale of tickets in the Philippines is the activity that produces the income. The tickets exchanged hands here and payments for fares were also made here in Philippine currency. The situs of the source of payments is the Philippines. The flow of wealth proceeded from, and occurred within, Philippine territory, enjoying the protection accorded by the Philippine government. In consideration of such protection, the flow of wealth should share the burden of supporting the government. In Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC),20 the issue was whether BOAC, a foreign airline company which does not maintain any flight to and from the Philippines is liable for Philippine income taxation in respect of sales of air tickets in the Philippines, through a general sales agent relating to the carriage of passengers and cargo between two points both outside the Philippines. Ruling in the affirmative, the Court applied the case of Alexander Howden & Co., Ltd. v. Collector of Internal Revenue, and reiterated the rule that the source of income is that "activity" which produced the income. It was held that the "sale of tickets" in the Philippines is the "activity" that produced the income and therefore BOAC should pay income tax in the Philippines because it undertook an income producing activity in the country. Both the petitioner and respondent cited the case of Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. British Overseas Airways Corporation in support of their arguments, but the correct interpretation of the said case favors the theory of respondent that it is the situs of the activity that determines whether such income is taxable in the Philippines. The conflict between the majority and the dissenting opinion in the said case has nothing to do with the underlying principle of the law on sourcing of income. In fact, both applied the case of Alexander Howden & Co., Ltd. v. Collector of Internal Revenue. The divergence in opinion centered on whether the sale of tickets in the Philippines is to be construed as the "activity" that produced the income, as viewed by the majority, or merely the physical source of the income, as ratiocinated by Justice Florentino P. Feliciano in his dissent. The majority, through Justice Ameurfina Melencio-Herrera, as ponente, interpreted the sale of tickets as a business activity that gave rise to the income of BOAC. Petitioner cannot therefore invoke said case to support its view that source of income is the physical source of the money earned. If such was the interpretation of the majority, the Court would have simply stated that source of income is not the business activity of BOAC but the place where the person or entity disbursing the income is located or where BOAC physically received the same. But such was not the import of the ruling of the Court. It even explained in detail the business activity undertaken by BOAC in the Philippines to pinpoint the taxable activity and to justify its conclusion that BOAC is subject to Philippine income taxation. Thus – BOAC, during the periods covered by the subject assessments, maintained a general sales agent in the Philippines. That general sales agent, from 1959 to 1971, "was engaged in (1) selling and issuing tickets; (2) breaking down the whole trip into series of trips — each trip in the series corresponding to a different airline company; (3) receiving the fare from the whole trip; and (4) consequently allocating to the various airline companies on the basis of their participation in the services rendered through the mode of interline settlement as prescribed by Article VI of the Resolution No. 850 of the IATA Agreement." Those activities were in exercise xxxx A transportation ticket is not a mere piece of paper. When issued by a common carrier, it constitutes the contract between the ticket-holder and the carrier. It gives rise to the obligation of the purchaser of the ticket to pay the fare and the corresponding obligation of the carrier to transport the passenger upon the terms and conditions set forth thereon. The ordinary ticket issued to members of the traveling public in general embraces within its terms all the elements to constitute it a valid contract, binding upon the parties entering into the relationship.22 The Court reiterates the rule that "source of income" relates to the property, activity or service that produced the income. With respect to rendition of labor or personal service, as in the instant case, it is the place where the labor or service was performed that determines the source of the income. There is therefore no merit in petitioner’s interpretation which equates source of income in labor or personal service with the residence of the payor or the place of payment of the income. Having disposed of the doctrine applicable in this case, we will now determine whether respondent was able to establish the factual circumstances showing that her income is exempt from Philippine income taxation. The decisive factual consideration here is not the capacity in which respondent received the income, but the sufficiency of evidence to prove that the services she rendered were performed in Germany. Though not raised as an issue, the Court is clothed with authority to address the same because the resolution thereof will settle the vital question posed in this controversy.23 The settled rule is that tax refunds are in the nature of tax exemptions and are to be construed strictissimi juris against the taxpayer.24 To those therefore, who claim a refund rest the burden of proving that the transaction subjected to tax is actually exempt from taxation. In the instant case, the appointment letter of respondent as agent of JUBANITEX stipulated that the activity or the service which would entitle her to 10% commission income, are "sales actually concluded and collected through [her] efforts."25 What she presented as evidence to prove that she performed income producing activities abroad, were copies of documents she allegedly faxed to JUBANITEX and bearing instructions as to the sizes of, or designs and fabrics to be used in the finished products as well as samples of sales orders purportedly relayed to her by clients. However, these documents do not show whether the instructions or orders faxed ripened into concluded or collected sales in Germany. At the very least, these pieces of evidence show that while respondent was in Germany, she sent instructions/orders to JUBANITEX. As to whether these instructions/orders gave rise to consummated sales and whether these sales were truly concluded in Germany, respondent presented no such evidence. Neither did she establish reasonable connection between the orders/instructions faxed and the reported monthly sales purported to have transpired in Germany. The paucity of respondent’s evidence was even noted by Atty. Minerva Pacheco, petitioner’s counsel at the hearing before the Court of Tax Appeals. She pointed out that respondent presented no contracts or orders signed by the customers in Germany to prove the sale transactions therein. 26 Likewise, in her Comment to the Formal Offer of respondent’s evidence, she objected to the admission of the faxed documents bearing instruction/orders marked as Exhibits "R," 27 "V," "W", and "X,"28 for being self serving.29 The concern raised by petitioner’s counsel as to the absence of substantial evidence that would constitute proof that the sale transactions for which respondent was paid commission actually transpired outside the Philippines, is relevant because respondent stayed in the Philippines for 89 days in 1995. Except for the months of July and September 1995, respondent was in the Philippines in the months of March, May, June, and August 1995, 30 the same months when she earned commission income for services allegedly performed abroad. Furthermore, respondent presented no evidence to prove that JUBANITEX does not sell embroidered products in the Philippines and that her appointment as commission agent is exclusively for Germany and other European markets. In sum, we find that the faxed documents presented by respondent did not constitute substantial evidence, or that relevant evidence that a reasonable mind might accept as adequate to support the conclusion 31 that it was in Germany where she performed the income producing service which gave rise to the reported monthly sales in the months of March and May to September of 1995. She thus failed to discharge the burden of proving that her income was from sources outside the Philippines and exempt from the application of our income tax law. Hence, the claim for tax refund should be denied. The Court notes that in Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Baier-Nickel,32 a previous case for refund of income withheld from respondent’s remunerations for services rendered abroad, the Court in a Minute Resolution dated February 17, 2003,33 sustained the ruling of the Court of Appeals that respondent is entitled to refund the sum withheld from her sales commission income for the year 1994. This ruling has no bearing in the instant controversy because the subject matter thereof is the income of respondent for the year 1994 while, the instant case deals with her income in 1995. Otherwise, stated, res judicata has no application here. Its elements are: (1) there must be a final judgment or order; (2) the court that rendered the judgment must have jurisdiction over the subject matter and the parties; (3) it must be a judgment on the merits; (4) there must be between the two cases identity of parties, of subject matter, and of causes of action. 34 The instant case, however, did not satisfy the fourth requisite because there is no identity as to the subject matter of the previous and present case of respondent which deals with income earned and activities performed for different taxable years. WHEREFORE, the petition is GRANTED and the January 18, 2002 Decision and May 8, 2002 Resolution of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 59794, are REVERSED and SET ASIDE. The June 28, 2000 Decision of the Court of Tax Appeals in C.T.A. Case No. 5633, which denied respondent’s claim for refund of income tax paid for the year 1995 is REINSTATED. SO ORDERED. HENARES, IN HER CAPACITY AS COMMISSIONER OF THE BUREAU OF INTERNAL REVENUE, RESPONDENT. THE MEMBERS OF THE ASSOCIATION OF REGIONAL TRIAL COURT JUDGES IN ILOILO CITY, INTERVENORS. DECISION CAGUIOA, J: G.R. No. 213446. July 03, 2018 CONFEDERATION FOR UNITY, RECOGNITION AND ADVANCEMENT OF GOVERNMENT EMPLOYEES (COURAGE); JUDICIARY EMPLOYEES ASSOCIATION OF THE PHILIPPINES (JUDEA-PHILS); SANDIGANBAYAN EMPLOYEES ASSOCIATION (SEA); SANDIGAN NG MGA EMPLEYADONG NAGKAKAISA SA ADHIKAIN NG DEMOKRATIKONG ORGANISASYON (S.E.N.A.D.O.); ASSOCIATION OF COURT OF APPEALS EMPLOYEES (ACAE); DEPARTMENT OF AGRARIAN REFORM EMPLOYEES ASSOCIATION (DAREA); SOCIAL WELFARE EMPLOYEES ASSOCIATION OF THE PHILIPPINESDEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL WELFARE AND DEVELOPMENT (SWEAP-DSWD); DEPARTMENT OF TRADE AND INDUSTRY EMPLOYEES UNION (DTI-EU); KAPISANAN PARA SA KAGALINGAN NG MGA KAWANI NG METRO MANILA DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (KKK-MMDA); WATER SYSTEM EMPLOYEES RESPONSE (WATER); CONSOLIDATED UNION OF EMPLOYEES OF THE NATIONAL HOUSING AUTHORITIES (CUE-NHA); AND KAPISANAN NG MGA MANGGAGAWA AT KAWANI NG QUEZON CITY (KASAMA KA-QC), PETITIONERS, V. COMMISSIONER, BUREAU OF INTERNAL REVENUE AND THE SECRETARY, DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE, RESPONDENTS. NATIONAL FEDERATION OF EMPLOYEES ASSOCIATIONS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE (NAFEDA), REPRESENTED BY ITS EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT ROMAN M. SANCHEZ, DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE EMPLOYEES ASSOCIATION OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY (DAEA-OSEC), REPRESENTED BY ITS ACTING PRESIDENT ROWENA GENETE, NATIONAL AGRICULTURAL AND FISHERIES COUNCIL EMPLOYEES ASSOCIATION (NAFCEA), REPRESENTED BY ITS PRESIDENT SOLIDAD B. BERNARDO, COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS EMPLOYEES UNION (COMELEC EU), REPRESENTED BY ITS PRESIDENT MARK CHRISTOPHER D. RAMIREZ, MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU EMPLOYEES ASSOCIATION CENTRAL OFFICE (MGBEA CO), REPRESENTED BY ITS PRESIDENT MAYBELLYN A. ZEPEDA, LIVESTOCK DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL EMPLOYEES ASSOCIATION (LDCEA), REPRESENTED BY ITS PRESIDENT JOVITA M. GONZALES, ASSOCIATION OF CONCERNED EMPLOYEES OF PHILIPPINE FISHERIES DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (ACE OF PFDA), REPRESENTED BY ITS PRESIDENT ROSARIO DEBLOIS, INTERVENORS. G.R. No. 213658, July 3, 2018 JUDGE ARMANDO A. YANGA, IN HIS PERSONAL CAPACITY AND IN HIS CAPACITY AS PRESIDENT OF THE RTC JUDGES ASSOCIATION OF MANILA, AND MA. CRISTINA CARMELA I. JAPZON, IN HER PERSONAL CAPACITY AND IN HER CAPACITY AS PRESIDENT OF THE PHILIPPINE ASSOCIATION OF COURT EMPLOYEES-MANILA CHAPTER, PETITIONERS, V. HON. COMMISSIONER KIM S. JACINTO- G.R. Nos. 213446 and 213658 are petitions for Certiorari, Prohibition and/or Mandamus under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court, with Application for Issuance of Temporary Restraining Order and/or Writ of Preliminary Injunction, uniformly seeking to: (a) issue a Temporary Restraining Order to enjoin the implementation of Revenue Memorandum Order (RMO) No. 23- 2014 dated June 20, 2014 issued by the Commissioner of Internal Revenue (CIR); and (b) declare null, void and unconstitutional paragraphs A, B, C, and D of Section III, and Sections IV, VI and VII of RMO No. 23-2014. The petition in G.R. No. 213446 also prays for the issuance of a Writ of Mandamus to compel respondents to upgrade the P30,000.00 non-taxable ceiling of the 13th month pay and other benefits for the concerned officials and employees of the government. The Antecedents On June 20, 2014, respondent CIR issued the assailed RMO No. 23-2014, in furtherance of Revenue Memorandum Circular (RMC) No. 23-2012 dated February 14, 2012 on the "Reiteration of the Responsibilities of the Officials and Employees of Government Offices for the Withholding of Applicable Taxes on Certain Income Payments and the Imposition of Penalties for Non-Compliance Thereof," in order to clarify and consolidate the responsibilities of the public sector to withhold taxes on its transactions as a customer (on its purchases of goods and services) and as an employer (on compensation paid to its officials and employees) under the National Internal Revenue Code (NIRC or Tax Code) of 1997, as amended, and other special laws. The Petitions G.R. No. 213446 On August 6, 2014, petitioners Confederation for Unity, Recognition and Advancement of Government Employees (COURAGE), et al., organizations/unions of government employees from the Sandiganbayan, Senate of the Philippines, Court of Appeals, Department of Agrarian Reform, Department of Social Welfare and Development, Department of Trade and Industry, Metro Manila Development Authority, National Housing Authority and local government of Quezon City, filed a Petition for Prohibition and Mandamus, [1] imputing grave abuse of discretion on the part of respondent CIR in issuing RMO No. 23-2014. According to petitioners, RMO No. 23-2014 classified as taxable compensation, the following allowances, bonuses, compensation for services granted to government employees, which they alleged to be considered by law as non-taxable fringe and de minimis benefits, to wit: I. Legislative Fringe Benefits a. b. c. d. e. f. g. h. i. j. k. l. m. n. o. p. q. Anniversary Bonus Additional Food Subsidy 13th Month Pay Food Subsidy Cash Gift Cost of Living Assistance Efficiency Incentive Bonus Financial Relief Assistance Grocery Allowance Hospitalization Inflationary Assistance Allowance Longevity Service Pay Medical Allowance Mid-Year Eco. Assistance Productivity Incentive Benefit Transition Allowance Uniform Allowance II. Judiciary Benefits a. b. c. d. e. f. g. h. i. j. k. l. Additional Compensation Income Extraordinary & Miscellaneous Expenses Monthly Special Allowance Additional Cost of Living Allowance (from Judiciary Development Fund) Productivity Incentive Benefit Grocery Allowance Clothing Allowance Emergency Economic Assistance Year-End Bonus (13th Month Pay) Cash Gift Loyalty Cash Award (Milestone Bonus) Christmas Allowance m. Anniversary Bonus[2] Petitioners further assert that the imposition of withholding tax on these allowances, bonuses and benefits, which have been allotted by the Government to its employees free of tax for a long time, violates the prohibition on non-diminution of benefits under Article 100 of the Labor Code; [3] and infringes upon the fiscal autonomy of the Legislature, Judiciary, Constitutional Commissions and Office of the Ombudsman granted by the Constitution.[4] Petitioners also claim that RMO No. 23-2014 (1) constitutes a usurpation of legislative power and diminishes the delegated power of local government units inasmuch as it defines new offenses and prescribes penalty therefor, particularly upon local government officials;[5] and (2) violates the equal protection clause of the Constitution as it discriminates against government officials and employees by imposing fringe benefit tax upon their allowances and benefits, as opposed to the allowances and benefits of employees of the private sector, the fringe benefit tax of which is borne and paid by their employers. [6] Further, the petition also prays for the issuance of a writ of mandamus ordering respondent CIR to perform its duty under Section 32(B)(7)(e)(iv) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, to upgrade the ceiling of the 13th month pay and other benefits for the concerned officials and employees of the government, including petitioners. [7] G.R. No. 213658 On August 19, 2014, petitioners Armando A. Yanga, President of the Regional Trial Court (RTC) Judges Association of Manila, and Ma. Cristina Carmela I. Japzon, President of the Philippine Association of Court Employees – Manila Chapter, filed a Petition for Certiorari and Prohibition [8] as duly authorized representatives of said associations, seeking to nullify RMO No. 23-2014 on the following grounds: (1) respondent CIR is bereft of any authority to issue the assailed RMO. The NIRC of 1997, as amended, expressly vests to the Secretary of Finance the authority to promulgate all needful rules and regulations for the effective enforcement of tax provisions;[9] and (2) respondent CIR committed grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction in the issuance of RMO No. 23-2014 when it subjected to withholding tax benefits and allowances of court employees which are tax-exempt such as: (a) Special Allowance for Judiciary (SAJ) under Republic Act (RA) No. 9227 and additional cost of living allowance (AdCOLA) granted under Presidential Decree (PD) No. 1949 which are considered as non-taxable fringe benefits under Section 33(A) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended; (b) cash gift, loyalty awards, uniform and clothing allowance and additional compensation (ADCOM) granted to court employees which are considered de minimis under Section 33(C)(4) of the same Code; (c) allowances and benefits granted by the Judiciary which are not taxable pursuant to Section 32(7)(E) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended; and (d) expenses for the Judiciary provided under Commission on Audit (COA) Circular 2012-001.[10] Petitioners further assert that RMO No. 23-2014 violates their right to due process of law because while it is ostensibly denominated as a mere revenue issuance, it is an illegal and unwarranted legislative action which sharply increased the tax burden of officials and employees of the Judiciary without the benefit of being heard. [11] On October 21, 2014, the Court resolved to consolidate the foregoing cases.[12] Respondents, through the Office of the Solicitor General (OSG), filed their Consolidated Comment[13] on December 23, 2014. They argue that the petitions are barred by the doctrine of hierarchy of courts and petitioners failed to present any special and important reasons or exceptional and compelling circumstance to justify direct recourse to this Court.[14] Maintaining that RMO No. 23-2014 was validly issued in accordance with the power of the CIR to make rulings and opinion in connection with the implementation of internal revenue laws, respondents aver that unlike Revenue Regulations (RRs), RMOs do not require the approval or signature of the Secretary of Finance, as these merely provide directives or instructions in the implementation of stated policies, goals, objectives, plans and programs of the Bureau.[15] According to them, RMO No. 23-2014 is in fact a mere reiteration of the Tax Code and previous RMOs, and can be traced back to RR No. 01-87 dated April 2, 1987 implementing Executive Order No. 651 which was promulgated by then Secretary of Finance Jaime V. Ongpin upon recommendation of then CIR Bienvenido A. Tan, Jr. Thus, the CIR never usurped the power and authority of the legislature in the issuance of the assailed RMO.[16] Also, contrary to petitioners' assertion, the due process requirements of hearing and publication are not applicable to RMO No. 23-2014.[17] Respondents further argue that petitioners' claim that RMO No. 23-2014 is unconstitutional has no leg to stand on. They explain that the constitutional guarantee of fiscal autonomy to Judiciary and Constitutional Commissions does not include exemption from payment of taxes, which is the lifeblood of the nation. [18] They also aver that RMO No. 23-2014 never intended to diminish the powers of local government units. It merely reiterates the obligation of the government as an employer to withhold taxes, which has long been provided by the Tax Code.[19] Moreover, respondents assert that the allowances and benefits enumerated in Section III A, B, C, and D, are not fringe benefits which are exempt from taxation under Section 33 of the Tax Code, nor de minimis benefits excluded from employees' taxable basic salary. They explain that the SAJ under RA No. 9227 and AdCOLA under PD No. 1949 are additional allowances which form part of the employee's basic salary; thus, subject to withholding taxes.[20] Judiciary; employees and officials in the executive and legislative do not receive this specific type of ADCOM enjoyed by the employees and officials of the Judicial branch.[31] On October 10, 2014, a Motion for Intervention with attached Complaint in Intervention [32] was filed, in G.R. No. 213658, by the Members of the Association of Regional Trial Court Judges in Iloilo City. Claiming that they are similarly situated with petitioners, said intervenors pray that the Court declare null and void RMO No. 23-2014 and direct the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) to refund the amount illegally exacted from the salaries/compensations of the judges by virtue of the implementation of RMO No. 23-2014.[33] The intervenors claim that RMO No. 23-2014 violates their right to due process as it takes away a portion of their salaries and compensation without giving them the opportunity to be heard. [34] They also aver that the implementation of RMO No. 23-2014 resulted in the diminution of their salaries/compensation in violation of Sections 3 and 10, Article VIII of the Constitution.[35] Lastly, respondents aver that mandamus will not lie to compel respondents to increase the ceiling for tax exemptions because the Tax Code does not impose a mandatory duty on the part of respondents to do the same.[22] In their Comment[36] to the Motion, respondents adopted the arguments in their Consolidated Comment and further stated that: (1) RMO No. 23-2014 does not diminish the salaries and compensation of members of the judiciary as it has been judicially settled that the imposition of taxes on salaries and compensation of judges and justices is not equivalent to diminution of the same; [37] (2) the allowances and benefits enumerated under Section III(B) of RMO No. 23-2014 are not fringe benefits exempt from taxation; [38] (3) the AdCOLA and SAJ are not fringe benefits as these are considered part of the basic salary of government employees subject to income tax;[39] and (4) there is no valid ground for the refund of the taxes withheld pursuant to RMO No. 232014.[40] The Petitions-in-Intervention In sum, petitioners and intervenors (collectively referred to as petitioners) argue that: Respondents also claim that RMO No. 23-2014 does not violate petitioners' right to equal protection of laws as it covers all employees and officials of the government. It does not create a new category of taxable income nor make taxable those which are not taxable but merely reflect those incomes which are deemed taxable under existing laws.[21] Meanwhile, on September 11, 2014, the National Federation of Employees Associations of the Department of Agriculture (NAFEDA) et al., duly registered union/association of employees of the Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural and Fisheries Council, Commission on Elections, Mines and Geosciences Bureau, and Philippine Fisheries Development Authority, claiming similar interest as petitioners in G.R. No. 213446, filed a Petition-in-Intervention[23] seeking the nullification of items III, VI and VII of RMO No. 23-2014 based on the following grounds: (1) that respondent CIR acted with grave abuse of discretion and usurped the power of the Legislature in issuing RMO No. 23-2014 which imposes additional taxes on government employees and prescribes penalties for government official's failure to withhold and remit the same; [24] (2) that RMO No. 232014 violates the equal protection clause because the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) was not included among the constitutional commissions covered by the issuance and the ADCOM of employees of the Judiciary was subjected to withholding tax but those received by employees of the Legislative and Executive branches are not;[25] and (3) that respondent CIR failed to upgrade the tax exemption ceiling for benefits under Section 32(B)(7) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended.[26] 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. RMO No. 23-2014 is ultra vires insofar as: a. Sections III and IV of RMO No. 23-2014, for subjecting to withholding taxes non-taxable allowances, bonuses and benefits received by government employees; b. Sections VI and VII, for defining new offenses and prescribing penalties therefor, particularly upon government officials; RMO No. 23-2014 violates the equal protection clause as it discriminates against government employees; RMO No. 23-2014 violates fiscal autonomy enjoyed by government agencies; The implementation of RMO No. 23-2014 results in diminution of benefits of government employees, a violation of Article 100 of the Labor Code; and Respondents may be compelled through a writ of mandamus to increase the tax-exempt ceiling for 13th month pay and other benefits. On the other hand, respondents counter that: Comment,[27] In its respondents, through the OSG, sought the denial of the Petition-in-Intervention for failure of the intervenors to seek prior leave of Court and to demonstrate that the existing consolidated petitions are not sufficient to protect their interest as parties affected by the assailed RMO. [28] They further contend that, contrary to the intervenors' position, the CHR is not exempt from the applicability of RMO No. 23-2014.[29] They explain that the enumeration of government offices and constitutional bodies covered by RMO No. 23-2014 is not exclusive; Section III thereof in fact states that RMO No. 23-2014 covers all employees of the public sector.[30] They also allege that the ADCOM referred to in Section III(B) of the assailed RMO is unique to the 1. 2. The instant consolidated petitions are barred by the doctrine of hierarchy of courts; The CIR did not abuse its discretion in the issuance of RMO No. 23-2014 because: a. It was issued pursuant to the CIR's power to interpret the NIRC of 1997, as amended, and other tax laws, under Section 4 of the NIRC of 1997, as amended; b. RMO No. 23-2014 does not discriminate against government employees. It does not create a new category of taxable income nor make taxable those which are exempt; c. RMO No. 23-2014 does not result in diminution of benefits; d. 3. The allowances, bonuses or benefits listed under Section III of the assailed RMO are not fringe benefits; e. The fiscal autonomy granted by the Constitution does not include tax exemption; and Mandamus does not lie against respondents because the NIRC of 1997, as amended, does not impose a mandatory duty upon them to increase the tax-exempt ceiling for 13th month pay and other benefits. Incidentally, in a related case docketed as A.M. No. 16-12-04-SC, the Court, on July 11, 2017, issued a Resolution directing the Fiscal Management and Budget Office of the Court to maintain the status quo by the non-withholding of taxes from the benefits authorized to be granted to judiciary officials and personnel, namely, the Mid-year Economic Assistance, the Year-end Economic Assistance, the Yuletide Assistance, the Special Welfare Assistance (SWA) and the Additional SWA, until such time that a decision is rendered in the instant consolidated cases. The Court's Ruling I. Procedural Non-exhaustion of administrative remedies. It is an unquestioned rule in this jurisdiction that certiorari under Rule 65 will only lie if there is no appeal, or any other plain, speedy and adequate remedy in the ordinary course of law against the assailed issuance of the CIR.[41] The plain, speedy and adequate remedy expressly provided by law is an appeal of the assailed RMO with the Secretary of Finance under Section 4 of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, to wit: SEC. 4. Power of the Commissioner to Interpret Tax Laws and to Decide Tax Cases. – The power to interpret the provisions of this Code and other tax laws shall be under the exclusive and original jurisdiction of the Commissioner, subject to review by the Secretary of Finance. The power to decide disputed assessments, refunds of internal revenue taxes, fees or other charges, penalties imposed in relation thereto, or other matters arising under this Code or other laws or portions thereof administered by the Bureau of Internal Revenue is vested in the Commissioner, subject to the exclusive appellate jurisdiction of the Court of Tax Appeals.[42] The CIR's exercise of its power to interpret tax laws comes in the form of revenue issuances, which include RMOs that provide "directives or instructions; prescribe guidelines; and outline processes, operations, activities, workflows, methods and procedures necessary in the implementation of stated policies, goals, objectives, plans and programs of the Bureau in all areas of operations, except auditing." [43] These revenue issuances are subject to the review of the Secretary of Finance. In relation thereto, Department of Finance Department Order No. 00702[44] issued by the Secretary of Finance laid down the procedure and requirements for filing an appeal from the adverse ruling of the CIR to the said office. A taxpayer is granted a period of thirty (30) days from receipt of the adverse ruling of the CIR to file with the Office of the Secretary of Finance a request for review in writing and under oath.[45] In Asia International Auctioneers, Inc. v. Parayno, Jr.,[46] the Court dismissed the petition seeking the nullification of RMC No. 31-2003 for failing to exhaust administrative remedies. The Court held: x x x It is settled that the premature invocation of the court's intervention is fatal to one's cause of action. If a remedy within the administrative machinery can still be resorted to by giving the administrative officer every opportunity to decide on a matter that comes within his jurisdiction, then such remedy must first be exhausted before the court's power of judicial review can be sought. The party with an administrative remedy must not only initiate the prescribed administrative procedure to obtain relief but also pursue it to its appropriate conclusion before seeking judicial intervention in order to give the administrative agency an opportunity to decide the matter itself correctly and prevent unnecessary and premature resort to the court.[47] The doctrine of exhaustion of administrative remedies is not without practical and legal reasons. For one thing, availment of administrative remedy entails lesser expenses and provides for a speedier disposition of controversies. It is no less true to state that courts of justice for reasons of comity and convenience will shy away from a dispute until the system of administrative redress has been completed and complied with so as to give the administrative agency concerned every opportunity to correct its error and to dispose of the case.[48] While there are recognized exceptions to this salutary rule, petitioners have failed to prove the presence of any of those in the instant case. Violation of the rule on hierarchy of courts. Moreover, petitioners violated the rule on hierarchy of courts as the petitions should have been initially filed with the CTA, having the exclusive appellate jurisdiction to determine the constitutionality or validity of revenue issuances. In The Philippine American Life and General Insurance Co. v. Secretary of Finance,[49] the Court held that rulings of the Secretary of Finance in its exercise of its power of review under Section 4 of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, are appealable to the CTA.[50] The Court explained that while there is no law which explicitly provides where rulings of the Secretary of Finance under the adverted to NIRC provision are appealable, Section 7(a)[51] of RA No. 1125, the law creating the CTA, is nonetheless sufficient, albeit impliedly, to include appeals from the Secretary's review under Section 4 of the NIRC of 1997, as amended. Moreover, echoing its pronouncements in City of Manila v. Grecia-Cuerdo,[52] that the CTA has the power of certiorari within its appellate jurisdiction, the Court declared that "it is now within the power of the CTA, through its power of certiorari, to rule on the validity of a particular administrative rule or regulation so long as it is within its appellate jurisdiction. Hence, it can now rule not only on the propriety of an assessment or tax treatment of a certain transaction, but also on the validity of the revenue regulation or revenue memorandum circular on which the said assessment is based."[53] Subsequently, in Banco de Oro v. Republic,[54] the Court, sitting En Banc, further held that the CTA has exclusive appellate jurisdiction to review, on certiorari, the constitutionality or validity of revenue issuances, even without a prior issuance of an assessment. The Court En Banc reasoned: We revert to the earlier rulings in Rodriguez, Leal, and Asia International Auctioneers, Inc. The Court of Tax Appeals has exclusive jurisdiction to determine the constitutionality or validity of tax laws, rules and regulations, and other administrative issuances of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue. Article VIII, Section 1 of the 1987 Constitution provides the general definition of judicial power: ARTICLE [VIII] JUDICIAL DEPARTMENT Section 1. The judicial power shall be vested in one Supreme Court and in such lower courts as may be established by law. Judicial power includes the duty of the courts of justice to settle actual controversies involving rights which are legally demandable and enforceable, and to determine whether or not there has been a grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction on the part of any branch or instrumentality of the Government. (Emphasis supplied) Based on this constitutional provision, this Court recognized, for the first time, in The City of Manila v. Hon. Grecia-Cuerdo, the Court of Tax Appeals' jurisdiction over petitions for certiorari assailing interlocutory orders issued by the Regional Trial Court in a local tax case. Thus: [W]hile there is no express grant of such power, with respect to the CTA, Section 1, Article VIII of the 1987 Constitution provides, nonetheless, that judicial power shall be vested in one Supreme Court and in such lower courts as may be established by law and that judicial power includes the duty of the courts of justice to settle actual controversies involving rights which are legally demandable and enforceable, and to determine whether or not there has been a grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction on the part of any branch or instrumentality of the Government. On the strength of the above constitutional provisions, it can be fairly interpreted that the power of the CTA includes that of determining whether or not there has been grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction on the part of the RTC in issuing an interlocutory order in cases falling within the exclusive appellate jurisdiction of the tax court. It, thus, follows that the CTA, by constitutional mandate, is vested with jurisdiction to issue writs of certiorari in these cases. (Emphasis in the original) This Court further explained that the Court of Tax Appeals' authority to issue writs of certiorari is inherent in the exercise of its appellate jurisdiction: A grant of appellate jurisdiction implies that there is included in it the power necessary to exercise it effectively, to make all orders that will preserve the subject of the action, and to give effect to the final determination of the appeal. It carries with it the power to protect that jurisdiction and to make the decisions of the court thereunder effective. The court, in aid of its appellate jurisdiction, has authority to control all auxiliary and incidental matters necessary to the efficient and proper exercise of that jurisdiction. For this purpose, it may, when necessary, prohibit or restrain the performance of any act which might interfere with the proper exercise of its rightful jurisdiction in cases pending before it. Lastly, it would not be amiss to point out that a court which is endowed with a particular jurisdiction should have powers which are necessary to enable it to act effectively within such jurisdiction. These should be regarded as powers which are inherent in its jurisdiction and the court must possess them in order to enforce its rules of practice and to suppress any abuses of its process and to defeat any attempted thwarting of such process. In this regard, Section 1 of RA 9282 states that the CTA shall be of the same level as the CA and shall possess all the inherent powers of a court of justice. Indeed, courts possess certain inherent powers which may be said to be implied from a general grant of jurisdiction, in addition to those expressly conferred on them. These inherent powers are such powers as are necessary for the ordinary and efficient exercise of jurisdiction; or are essential to the existence, dignity and functions of the courts, as well as to the due administration of justice; or are directly appropriate, convenient and suitable to the execution of their granted powers; and include the power to maintain the court's jurisdiction and render it effective in behalf of the litigants. Thus, this Court has held that "while a court may be expressly granted the incidental powers necessary to effectuate its jurisdiction, a grant of jurisdiction, in the absence of prohibitive legislation, implies the necessary and usual incidental powers essential to effectuate it, and, subject to existing laws and constitutional provisions, every regularly constituted court has power to do all things that are reasonably necessary for the administration of justice within the scope of its jurisdiction and for the enforcement of its judgments and mandates." Hence, demands, matters or questions ancillary or incidental to, or growing out of, the main action, and coming within the above principles, may be taken cognizance of by the court and determined, since such jurisdiction is in aid of its authority over the principal matter, even though the court may thus be called on to consider and decide matters which, as original causes of action, would not be within its cognizance. (Citations omitted) Judicial power likewise authorizes lower courts to determine the constitutionality or validity of a law or regulation in the first instance. This is contemplated in the Constitution when it speaks of appellate review of final judgments of inferior courts in cases where such constitutionality is in issue. On June 16, 1954, Republic Act No. 1125 created the Court of Tax Appeals not as another superior administrative agency as was its predecessor — the former Board of Tax Appeals — but as a part of the judicial system with exclusive jurisdiction to act on appeals from: (1) Decisions of the Collector of Internal Revenue in cases involving disputed assessments, refunds of internal revenue taxes, fees or other charges, penalties imposed in relation thereto, or other matters arising under the National Internal Revenue Code or other law or part of law administered by the Bureau of Internal Revenue; (2) Decisions of the Commissioner of Customs in cases involving liability for customs duties, fees or other money charges; seizure, detention or release of property affected fines, forfeitures or other penalties imposed in relation thereto; or other matters arising under the Customs Law or other law or part of law administered by the Bureau of Customs; and (3) Decisions of provincial or city Boards of Assessment Appeals in cases involving the assessment and taxation of real property or other matters arising under the Assessment Law, including rules and regulations relative thereto. Republic Act No. 1125 transferred to the Court of Tax Appeals jurisdiction over all matters involving assessments that were previously cognizable by the Regional Trial Courts (then courts of first instance). In 2004, Republic Act No. 9282 was enacted. It expanded the jurisdiction of the Court of Tax Appeals and elevated its rank to the level of a collegiate court with special jurisdiction. Section 1 specifically provides that the Court of Tax Appeals is of the same level as the Court of Appeals and possesses "all the inherent powers of a Court of Justice." 6) Decisions of the Secretary of Finance on customs cases elevated to him automatically for review from decisions of the Commissioner of Customs which are adverse to the Government under Section 2315 of the Tariff and Customs Code; Section 7, as amended, grants the Court of Tax Appeals the exclusive jurisdiction to resolve all tax-related issues: 7) Decisions of the Secretary of Trade and Industry, in the case of nonagricultural product, commodity or article, and the Secretary of Agriculture in the case of agricultural product, commodity or article, involving dumping and countervailing duties under Section 301 and 302, respectively, of the Tariff and Customs Code, and safeguard measures under Republic Act No. 8800, where either party may appeal the decision to impose or not to impose said duties. Section 7. Jurisdiction. — The CTA shall exercise: (a) Exclusive appellate jurisdiction to review by appeal, as herein provided: 1) Decisions of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue in cases involving disputed assessments, refunds of internal revenue taxes, fees or other charges, penalties in relation thereto, or other matters arising under the National Internal Revenue Code or other laws administered by the Bureau of Internal Revenue; 2) Inaction by the Commissioner of Internal Revenue in cases involving disputed assessments, refunds of internal revenue taxes, fees or other charges, penalties in relation thereto, or other matters arising under the National Internal Revenue Code or other laws administered by the Bureau of Internal Revenue, where the National Internal Revenue Code provides a specific period of action, in which case the inaction shall be deemed a denial; 3) Decisions, orders or resolutions of the Regional Trial Courts in local tax cases originally decided or resolved by them in the exercise of their original or appellate jurisdiction; 4) Decisions of the Commissioner of Customs in cases involving liability for customs duties, fees or other money charges, seizure, detention or release of property affected, fines, forfeitures or other penalties in relation thereto, or other matters arising under the Customs Law or other laws administered by the Bureau of Customs; 5) Decisions of the Central Board of Assessment Appeals in the exercise of its appellate jurisdiction over cases involving the assessment and taxation of real property originally decided by the provincial or city board of assessment appeals; The Court of Tax Appeals has undoubted jurisdiction to pass upon the constitutionality or validity of a tax law or regulation when raised by the taxpayer as a defense in disputing or contesting an assessment or claiming a refund. It is only in the lawful exercise of its power to pass upon all matters brought before it, as sanctioned by Section 7 of Republic Act No. 1125, as amended. This Court, however, declares that the Court of Tax Appeals may likewise take cognizance of cases directly challenging the constitutionality or validity of a tax law or regulation or administrative issuance (revenue orders, revenue memorandum circulars, rulings). Section 7 of Republic Act No. 1125, as amended, is explicit that, except for local taxes, appeals from the decisions of quasi-judicial agencies (Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Commissioner of Customs, Secretary of Finance, Central Board of Assessment Appeals, Secretary of Trade and Industry) on tax-related problems must be brought exclusively to the Court of Tax Appeals. In other words, within the judicial system, the law intends the Court of Tax Appeals to have exclusive jurisdiction to resolve all tax problems. Petitions for writs of certiorari against the acts and omissions of the said quasijudicial agencies should, thus, be filed before the Court of Tax Appeals. Republic Act No. 9282, a special and later law than Batas Pambansa Blg. 129 provides an exception to the original jurisdiction of the Regional Trial Courts over actions questioning the constitutionality or validity of tax laws or regulations. Except for local tax cases, actions directly challenging the constitutionality or validity of a tax law or regulation or administrative issuance may be filed directly before the Court of Tax Appeals. Furthermore, with respect to administrative issuances (revenue orders, revenue memorandum circulars, or rulings), these are issued by the Commissioner under its power to make rulings or opinions in connection with the implementation of the provisions of internal revenue laws. Tax rulings, on the other hand, are official positions of the Bureau on inquiries of taxpayers who request clarification on certain provisions of the National Internal Revenue Code, other tax laws, or their implementing regulations. Hence, the determination of the validity of these issuances clearly falls within the exclusive appellate jurisdiction of the Court of Tax Appeals under Section 7(1) of Republic Act No. 1125, as amended, subject to prior review by the Secretary of Finance, as required under Republic Act No. 8424.[55] A direct invocation of this Court's jurisdiction should only be allowed when there are special, important and compelling reasons clearly and specifically spelled out in the petition.[56] Nevertheless, despite the procedural infirmities of the petitions that warrant their outright dismissal, the Court deems it prudent, if not crucial, to take cognizance of, and accordingly act on, the petitions as they assail the validity of the actions of the CIR that affect thousands of employees in the different government agencies and instrumentalities. The Court, following recent jurisprudence, avails itself of its judicial prerogative in order not to delay the disposition of the case at hand and to promote the vital interest of justice. As the Court held in Bloomberry Resorts and Hotels, Inc. v. Bureau of Internal Revenue:[57] From the foregoing jurisprudential pronouncements, it would appear that in questioning the validity of the subject revenue memorandum circular, petitioner should not have resorted directly before this Court considering that it appears to have failed to comply with the doctrine of exhaustion of administrative remedies and the rule on hierarchy of courts, a clear indication that the case was not yet ripe for judicial remedy. Notably, however, in addition to the justifiable grounds relied upon by petitioner for its immediate recourse (i.e., pure question of law, patently illegal act by the BIR, national interest, and prevention of multiplicity of suits), we intend to avail of our jurisdictional prerogative in order not to further delay the disposition of the issues at hand, and also to promote the vital interest of substantial justice. To add, in recent years, this Court has consistently acted on direct actions assailing the validity of various revenue regulations, revenue memorandum circulars, and the likes, issued by the CIR. The position we now take is more in accord with latest jurisprudence. x x x [58] II. Substantive The petitions assert that the CIR's issuance of RMO No. 23-2014, particularly Sections III, IV, VI and VII thereof, is tainted with grave abuse of discretion. "By grave abuse of discretion is meant, such capricious and whimsical exercise of judgment as is equivalent to lack of jurisdiction." [59] It is an evasion of a positive duty or a virtual refusal to perform a duty enjoined by law or to act in contemplation of law as when the judgment rendered is not based on law and evidence but on caprice, whim and despotism.[60] As earlier stated, Section 4 of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, grants the CIR the power to issue rulings or opinions interpreting the provisions of the NIRC or other tax laws. However, the CIR cannot, in the exercise of such power, issue administrative rulings or circulars inconsistent with the law sought to be applied. Indeed, administrative issuances must not override, supplant or modify the law, but must remain consistent with the law they intend to carry out.[61] The courts will not countenance administrative issuances that override, instead of remaining consistent and in harmony with the law they seek to apply and implement. [62] Thus, in Philippine Bank of Communications v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue,[63] the Court upheld the nullification of RMC No. 7-85 issued by the Acting Commissioner of Internal Revenue because it was contrary to the express provision of Section 230 of the NIRC of 1977. Also, in Banco de Oro v. Republic,[64] the Court nullified BIR Ruling Nos. 370-2011 and DA 378-2011 because they completely disregarded the 20 or more-lender rule added by Congress in the NIRC of 1997, as amended, and created a distinction for government debt instruments as against those issued by private corporations when there was none in the law.[65] Conversely, if the assailed administrative rule conforms with the law sought to be implemented, the validity of said issuance must be upheld. Thus, in The Philippine American Life and General Insurance Co. v. Secretary of Finance,[66] the Court declared valid Section 7 (c.2.2) of RR No. 06-08 and RMC No. 25-11, because they merely echoed Section 100 of the NIRC that the amount by which the fair market value of the property exceeded the value of the consideration shall be deemed a gift; thus, subject to donor's tax.[67] In this case, the Court finds the petitions partly meritorious only insofar as Section VI of the assailed RMO is concerned. On the other hand, the Court upholds the validity of Sections III, IV and VII thereof as these are in fealty to the provisions of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, and its implementing rules. Sections III and IV of RMO No. 23-2014 are valid. Compensation income is the income of the individual taxpayer arising from services rendered pursuant to an employer-employee relationship.[68] Under the NIRC of 1997, as amended, every form of compensation for services, whether paid in cash or in kind, is generally subject to income tax and consequently to withholding tax.[69] The name designated to the compensation income received by an employee is immaterial. [70] Thus, salaries, wages, emoluments and honoraria, allowances, commissions, fees, (including director's fees, if the director is, at the same time, an employee of the employer/corporation), bonuses, fringe benefits (except those subject to the fringe benefits tax under Section 33 of the Tax Code), pensions, retirement pay, and other income of a similar nature, constitute compensation income[71] that are taxable and subject to withholding. The withholding tax system was devised for three primary reasons, namely: (1) to provide the taxpayer a convenient manner to meet his probable income tax liability; (2) to ensure the collection of income tax which can otherwise be lost or substantially reduced through failure to file the corresponding returns; and (3) to improve the government's cash flow.[72] This results in administrative savings, prompt and efficient collection of taxes, prevention of delinquencies and reduction of governmental effort to collect taxes through more complicated means and remedies.[73] Section 79(A) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, states: SEC. 79. Income Tax Collected at Source. – (A) Requirement of Withholding - Except in the case of a minimum wage earner as defined in Section 22(HH) of this Code, every employer making payment of wages shall deduct and withhold upon such wages a tax determined in accordance with the rules and regulations to be prescribed by the Secretary of Finance, upon recommendation of the Commissioner.[74] In relation to the foregoing, Section 2.78 of RR No. 2-98,[75] as amended, issued by the Secretary of Finance to implement the withholding tax system under the NIRC of 1997, as amended, provides: SECTION 2.78. Withholding Tax on Compensation. — The withholding of tax on compensation income is a method of collecting the income tax at source upon receipt of the income. It applies to all employed individuals whether citizens or aliens, deriving income from compensation for services rendered in the Philippines. The employer is constituted as the withholding agent.[76] Section 2.78.3 of RR No. 2-98 further states that the term employee "covers all employees, including officers and employees, whether elected or appointed, of the Government of the Philippines, or any political subdivision thereof or any agency or instrumentality"; while an employer, as Section 2.78.4 of the same regulation provides, "embraces not only an individual and an organization engaged in trade or business, but also includes an organization exempt from income tax, such as charitable and religious organizations, clubs, social organizations and societies, as well as the Government of the Philippines, including its agencies, instrumentalities, and political subdivisions." The law is therefore clear that withholding tax on compensation applies to the Government of the Philippines, including its agencies, instrumentalities, and political subdivisions. The Government, as an employer, is constituted as the withholding agent, mandated to deduct, withhold and remit the corresponding tax on compensation income paid to all its employees. However, not all income payments to employees are subject to withholding tax. The following allowances, bonuses or benefits, excluded by the NIRC of 1997, as amended, from the employee's compensation income, are exempt from withholding tax on compensation: 1. Retirement benefits received under RA No. 7641 and those received by officials and employees of private firms, whether individual or corporate, under a reasonable private benefit plan maintained by the employer subject to the requirements provided by the Code [Section 32(B)(6)(a) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended and Section 2.78.1(B)(1)(a) of RR No. 2-98]; 2. Any amount received by an official or employee or by his heirs from the employer due to death, sickness or other physical disability or for any cause beyond the control of the said official or employee, such as retrenchment, redundancy, or cessation of business [Section 32(B)(6)(b) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended and Section 2.78.1(B)(1)(b) of RR No. 2-98]; 3. Social security benefits, retirement gratuities, pensions and other similar benefits received by residents or non-resident citizens of the Philippines or aliens who come to reside permanently in the Philippines from foreign government agencies and other institutions private or public [Section 32(B)(6)(c) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended and Section 2.78.1(B)(1)(c) of RR No. 2-98]; 4. Payments of benefits due or to become due to any person residing in the Philippines under the law of the United States administered by the United States Veterans Administration [Section 32(B)(6)(d) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended and Section 2.78.1(B)(1)(d) of RR No. 2-98]; 5. Payments of benefits made under the Social Security System Act of 1954 as amended [Section 32(B)(6)(e) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended and Section 2.78.1(B)(1)(e) of RR No. 2-98]; 6. Benefits received from the GSIS Act of 1937, as amended, and the retirement gratuity received by government officials and employees [Section 32(B)(6)(f) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended and Section 2.78.1(B)(1)(f) of RR No.2- 98]; 7. Thirteenth (13th) month pay and other benefits received by officials and employees of public and private entities not exceeding P82,000.00 [Section 32(B)(7)(e) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, and Section 2.78.1(8)(11) of RR No. 2-98, as amended by RR No. 03-15]; 8. GSIS, SSS, Medicare and Pag-Ibig contributions, and union dues of individual employees [Section 32(B)(7)(f) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended and Section 2.78.1(8)(12) of RR No. 2-98]; 9. Remuneration paid for agricultural labor [Section 2.78.1 (B)(2) of RR No. 2-98]; 10. Remuneration for domestic services [Section 28, RA No. 10361 and Section 2.78.1 (B)(3) of RR No. 2-98]; 11. Remuneration for casual labor not in the course of an employer's trade or business [Section 2.78.1(8)(4) of RR No. 2-98]; 12. Remuneration not more than the statutory minimum wage and the holiday pay, overtime pay, night shift differential pay and hazard pay received by Minimum Wage Earners [Section 24(A)(2) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended]; 13. Compensation for services by a citizen or resident of the Philippines for a foreign government or an international organization [Section 2.78.1(8)(5) of RR No. 2-98]; 14. Actual, moral, exemplary and nominal damages received by an employee or his heirs pursuant to a final judgment or compromise agreement arising out of or related to an employer-employee relationship [Section 32(B)(4) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended and Section 2.78.1 (B)(6) of RR No. 2-98]; 15. The proceeds of life insurance policies paid to the heirs or beneficiaries upon the death of the insured, whether in a single sum or otherwise, provided however, that interest payments agreed under the policy for the amounts which are held by the insured under such an agreement shall be included in the gross income [Section 32(B)(1) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended and Section 2.78.1 (B)(7) of RR No. 2-98]; 16. The amount received by the insured, as a return of premium or premiums paid by him under life insurance, endowment, or annuity contracts either during the term or at the maturity of the term mentioned in the contract or upon surrender of the contract [Section 32(8)(2) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended and Section 2.78.1(B)(8) of RR No. 2-98]; 17. Amounts received through Accident or Health Insurance or under Workmen's Compensation Acts, as compensation for personal injuries or sickness, plus the amount of any damages received whether by suit or agreement on account of such injuries or sickness [Section 32(8)(4) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended and Section 2.78.1(8)(9) of RR No. 2-98]; 18. Income of any kind to the extent required by any treaty obligation binding upon the Government of the Philippines [Section 32(8)(5) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended and Section 2.78.1(B)(10) of RR No. 2-98]; 19. Fringe and De minimis Benefits. [Section 33(C) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended); and 20. Other income received by employees which are exempt under special laws (RATA granted to public officers and employees under the General Appropriations Act and Personnel Economic Relief Allowance granted to government personnel). Petitioners assert that RMO No. 23-2014 went beyond the provisions of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, insofar as Sections III and IV thereof impose new or additional taxes to allowances, benefits or bonuses granted to government employees. A closer look at the assailed Sections, however, reveals otherwise. For reference, Sections III and IV of RMO No. 23-2014 read, as follows: III. OBLIGATION TO WITHHOLD ON COMPENSATION PAID TO GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS AND EMPLOYEES As an employer, government offices including government-owned or controlled corporations (such as but not limited to the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System, Philippine Deposit Insurance Corporation, Government Service Insurance System, Social Security System), as well as provincial, city and municipal governments are constituted as withholding agents for purposes of the creditable tax required to be withheld from compensation paid for services of its employees. Under Section 32(A) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, compensation for services, in whatever form paid and no matter how called, form part of gross income. Compensation income includes, among others, salaries, fees, wages, emoluments and honoraria, allowances, commissions (e.g. transportation, representation, entertainment and the like); fees including director's fees, if the director is, at the same time, an employee of the employer/corporation; taxable bonuses and fringe benefits except those which are subject to the fringe benefits tax under Section 33 of the NIRC; taxable pensions and retirement pay; and other income of a similar nature. Other than those pertaining to intelligence funds duly appropriated and liquidated, any amount not in compliance with the foregoing requirements shall be considered as part of the gross taxable compensation income of the taxpayer. Intelligence funds not duly appropriated and not properly liquidated shall form part of the compensation of the government officials/personnel concerned, unless returned. The foregoing also includes allowances, bonuses, and other benefits of similar nature received by officials and employees of the Government of the Republic of the Philippines or any of its branches, agencies and instrumentalities, its political subdivisions, including government-owned and/or controlled corporations (herein referred to as officials and employees in the public sector) which are composed of (but are not limited to) the following: IV. NON-TAXABLE COMPENSATION INCOME – Subject to existing laws and issuances, the following income received by the officials and employees in the public sector are not subject to income tax and withholding tax on compensation: A. B. C. D. Allowances, bonuses, honoraria or benefits received by employees and officials in the Legislative Branch, such as anniversary bonus, Special Technical Assistance Allowance, Efficiency Incentive Benefits, Additional Food Subsidy, Eight[h] (8 th) Salary Range Level Allowance, Hospitalization Benefits, Medical Allowance, Clothing Allowance, Longevity Pay, Food Subsidy, Transition Allowance, Cost of Living Allowance, Inflationary Adjustment Assistance, Mid-Year Economic Assistance, Financial Relief Assistance, Grocery Allowance, Thirteenth (13th Month Pay, Cash Gift and Productivity Incentive Benefit and other allowances, bonuses and benefits given by the Philippine Senate and House of Representatives to their officials and employees, subject to the exemptions enumerated herein. Allowances, bonuses, honoraria or benefits received by employees and officials in the Judicial Branch, such as the Additional Compensation (ADCOM), Extraordinary and Miscellaneous Expenses (EME), Monthly Special Allowance from the Special Allowance for the Judiciary, Additional Cost of Living Allowance from the Judiciary Development Fund, Productivity Incentive Benefit, Grocery Allowance, Clothing Allowance, Emergency Economic Allowance, Year-End Bonus, Cash Gift, Loyalty Cash Award (Milestone Bonus), SC Christmas Allowance, anniversary bonuses and other allowances, bonuses and benefits given by the Supreme Court of the Philippines and all other courts and offices under the Judicial Branch to their officials and employees, subject to the exemptions enumerated herein. Compensation for services in whatever form paid, including, but not limited to allowances, bonuses, honoraria or benefits received by employees and officials in the Constitutional bodies (Commission on Election, Commission on Audit, Civil Service Commission) and the Office of the Ombudsman, subject to the exemptions enumerated herein. Allowances, bonuses, honoraria or benefits received by employees and officials in the Executive Branch, such as the Productivity Enhancement Incentive (PEI), Performance-Based Bonus, anniversary bonus and other allowances, bonuses and benefits given by the departments, agencies and other offices under the Executive Branch to their officials and employees, subject to the exemptions enumerated herein. Any amount paid either as advances or reimbursements for expenses incurred or reasonably expected to be incurred by the official and employee in the performance of his/her duties are not compensation subject to withholding, if the following conditions are satisfied: 1. 2. The employee was duly authorized to incur such expenses on behalf of the government; and Compliance with pertinent laws and regulations on accounting and liquidation of advances and reimbursements, including, but not limited to withholding tax rules. The expenses should be duly receipted for and in the name of the government office concerned. Thirteenth (13th Month Pay and Other Benefits not exceeding Thirty Thousand Pesos (P30,000.00) paid or accrued during the year. Any amount exceeding Thirty Thousand Pesos (P30,000.00) are taxable compensation. This includes: 1. Benefits received by officials and employees of the national and local government pursuant to Republic Act no. 6686 ("An Act Authorizing Annual Christmas Bonus to National and Local Government Officials and Employees Starting CY 1998"); 2. Benefits received by employees pursuant to Presidential Decree No. 851 ("Requiring All Employers to Pay Their Employees a 13 th Month Pay"), as amended by Memorandum Order No. 28, dated August 13, 1986; 3. Benefits received by officials and employees not covered by Presidential Decree No. 851, as amended by Memorandum Order No. 28, dated August 19, 1986; 4. Other benefits such as Christmas bonus, productivity incentive bonus, loyalty award, gift in cash or in kind and other benefits of similar nature actually received by officials and employees of government offices, including the additional compensation allowance (ACA) granted and paid to all officials and employees of the National Government Agencies (NGAs) including state universities and colleges (SUCs), government-owned and/or controlled corporations (GOCCs), government financial institutions (GFIs) and Local Government Units (LGUs). B. Facilities and privileges of relatively small value or "De Minimis Benefits" as defined in existing issuances and conforming to the ceilings prescribed therein; C. Fringe benefits which are subject to the fringe benefits tax under Section 33 of the NIRC, as amended; D. Representation and Transportation Allowance (RATA) granted to public officers and employees under the General Appropriations Act; E. Personnel Economic Relief Allowance (PERA) granted to government personnel; F. The monetized value of leave credits paid to government officials and employees; G. Mandatory/compulsory GSIS, Medicare and Pag-Ibig Contributions, provided that, voluntary contributions to these institutions in excess of the amount considered mandatory/compulsory are not excludible from the gross income of the taxpayer and hence, not exempt from Income Tax and Withholding Tax; H. Union dues of individual employees; I. Compensation income of employees in the public sector with compensation income of not more than the Statutory Minimum Wage (SMW) in the non-agricultural sector applicable to the place where he/she is assigned; J. Holiday pay, overtime pay, night shift differential pay, and hazard pay received by Minimum Wage Earners (MWEs); K. Benefits received from the GSIS Act of 1937, as amended, and the retirement gratuity/benefits received by government officials and employees under pertinent retirement laws; A. L. All other benefits given which are not included in the above enumeration but are exempted from income tax as well as withholding tax on compensation under existing laws, as confirmed by BIR.[77] Clearly, Sections III and IV of the assailed RMO do not charge any new or additional tax. On the contrary, they merely mirror the relevant provisions of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, and its implementing rules on the withholding tax on compensation income as discussed above. The assailed Sections simply reinforce the rule that every form of compensation for personal services received by all employees arising from employeremployee relationship is deemed subject to income tax and, consequently, to withholding tax, [78] unless specifically exempted or excluded by the Tax Code; and the duty of the Government, as an employer, to withhold and remit the correct amount of withholding taxes due thereon. While Section III enumerates certain allowances which may be subject to withholding tax, it does not exclude the possibility that these allowances may fall under the exemptions identified under Section IV – thus, the phrase, "subject to the exemptions enumerated herein." In other words, Sections III and IV articulate in a general and broad language the provisions of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, on the forms of compensation income deemed subject to withholding tax and the allowances, bonuses and benefits exempted therefrom. Thus, Sections III and IV cannot be said to have been issued by the CIR with grave abuse of discretion as these are fully in accordance with the provisions of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, and its implementing rules. Furthermore, the Court finds untenable petitioners' contention that the assailed provisions of RMO No. 23-2014 contravene the equal protection clause, fiscal autonomy, and the rule on non-diminution of benefits. The constitutional guarantee of equal protection is not violated by an executive issuance which was issued to simply reinforce existing taxes applicable to both the private and public sector. As discussed, the withholding tax system embraces not only private individuals, organizations and corporations, but also covers organizations exempt from income tax, including the Government of the Philippines, its agencies, instrumentalities, and political subdivisions. While the assailed RMO is a directive to the Government, as a reminder of its obligation as a withholding agent, it did not, in any manner or form, alter or amend the provisions of the Tax Code, for or against the Government or its employees. Moreover, the fiscal autonomy enjoyed by the Judiciary, Ombudsman, and Constitutional Commissions, as envisioned in the Constitution, does not grant immunity or exemption from the common burden of paying taxes imposed by law. To borrow former Chief Justice Corona's words in his Separate Opinion in Francisco, Jr. v. House of Representatives,[79] "fiscal autonomy entails freedom from outside control and limitations, other than those provided by law. It is the freedom to allocate and utilize funds granted by law, in accordance with law and pursuant to the wisdom and dispatch its needs may require from time to time." [80] It bears to emphasize the Court's ruling in Nitafan v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue[81] that the imposition of taxes on salaries of Judges does not result in diminution of benefits. This applies to all government employees because the intent of the framers of the Organic Law and of the people adopting it is "that all citizens should bear their aliquot part of the cost of maintaining the government and should share the burden of general income taxation equitably."[82] Determination of existence of fringe benefits is a question of fact. Petitioners, nonetheless, insist that the allowances, bonuses and benefits enumerated in Section III of the assailed RMO are, in fact, fringe and de minimis benefits exempt from withholding tax on compensation. The Court cannot, however, rule on this issue as it is essentially a question of fact that cannot be determined in this petition questioning the constitutionality of the RMO. To be sure, settled is the rule that exemptions from tax are construed strictissimi juris against the taxpayer and liberally in favor of the taxing authority. [83] One who claims tax exemption must point to a specific provision of law conferring, in clear and plain terms, exemption from the common burden[84] and prove, through substantial evidence, that it is, in fact, covered by the exemption so claimed. [85] The determination, therefore, of the merits of petitioners' claim for tax exemption would necessarily require the resolution of both legal and factual issues, which this Court, not being a trier of facts, has no jurisdiction to do; more so, in a petition filed at first instance. Among the factual issues that need to be resolved, at the first instance, is the nature of the fringe benefits granted to employees. The NIRC of 1997, as amended, does not impose income tax, and consequently a withholding tax, on payments to employees which are either (a) required by the nature of, or necessary to, the business of the employer; or (b) for the convenience or advantage of the employer. [86] This, however, requires proper documentation. Without any documentary proof that the payment ultimately redounded to the benefit of the employer, the same shall be considered as a taxable benefit to the employee, and hence subject to withholding taxes.[87] Another factual issue that needs to be confirmed is the recipient of the alleged fringe benefit. Fringe benefits furnished or granted, in cash or in kind, by an employer to its managerial or supervisory employees, are not considered part of compensation income; thus, exempt from withholding tax on compensation. [88] Instead, these fringe benefits are subject to a fringe benefit tax equivalent to 32% of the grossed-up monetary value of the benefit, which the employer is legally required to pay.[89] On the other hand, fringe benefits given to rank and file employees, while exempt from fringe benefit tax,[90] form part of compensation income taxable under the regular income tax rates provided in Section 24(A)(2) of the NIRC, of 1997, as amended;[91] and consequently, subject to withholding tax on compensation. Furthermore, fringe benefits of relatively small value furnished by the employer to his employees (both managerial/supervisory and rank and file) as a means of promoting health, goodwill, contentment, or efficiency, otherwise known as de minimis benefits, that are exempt from both income tax on compensation and fringe benefit tax; hence, not subject to withholding tax,[92] are limited and exclusive only to those enumerated under RR No. 3-98, as amended.[93] All other benefits given by the employer which are not included in the said list, although of relatively small value, shall not be considered as de minimis benefits; hence, shall be subject to income tax as well as withholding tax on compensation income, for rank and file employees, or fringe benefits tax for managerial and supervisory employees, as the case may be. [94] Based on the foregoing, it is clear that to completely determine the merits of petitioners' claimed exemption from withholding tax on compensation, under Section 33 of the NIRC of 1997, there is a need to confirm several factual issues. As such, petitioners cannot but first resort to the proper courts and administrative agencies which are better equipped for said task. All told, the Court finds Sections III and IV of the assailed RMO valid. The NIRC of 1997, as amended, is clear that all forms of compensation income received by the employee from his employer are presumed taxable and subject to withholding taxes. The Government of the Philippines, its agencies, instrumentalities, and political subdivisions, as an employer, is required by law to withhold and remit to the BIR the appropriate taxes due thereon. Any claims of exemption from withholding taxes by an employee, as in the case of petitioners, must be brought and resolved in the appropriate administrative and judicial proceeding, with the employee having the burden to prove the factual and legal bases thereof. Section VII of RMO No. 23-2014 is valid; Section VI contravenes, in part, the provisions of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, and its implementing rules. Petitioners claim that RMO No. 23-2014 is ultra vires insofar as Sections VI and VII thereof define new offenses and prescribe penalties therefor, particularly upon government officials. SEC. 251. Failure of a Withholding Agent to Collect and Remit Tax. – Any person required to withhold, account for, and remit any tax imposed by this Code or who willfully fails to withhold such tax, or account for and remit such tax, or aids or abets in any manner to evade any such tax or the payment thereof, shall, in addition to other penalties provided for under this Chapter, be liable upon conviction to a penalty equal to the total amount of the tax not withheld, or not accounted for and remitted.[97] SEC. 252. Failure of a Withholding Agent to Refund Excess Withholding Tax. – Any employer/withholding agent who fails or refuses to refund excess withholding tax shall, in addition to the penalties provided in this Title, be liable to a penalty equal to the total amount of refunds which was not refunded to the employee resulting from any excess of the amount withheld over the tax actually due on their return. CHAPTER Crimes, Other Offenses and Forfeitures II xxxx The NIRC of 1997, as amended, clearly provides the offenses and penalties relevant to the obligation of the withholding agent to deduct, withhold and remit the correct amount of withholding taxes on compensation income, to wit: TITLE Statutory Offenses and Penalties CHAPTER Additions to the Tax X I SEC. 247. General Provisions. – (a) The additions to the tax or deficiency tax prescribed in this Chapter shall apply to all taxes, fees and charges imposed in this Code. The amount so added to the tax shall be collected at the same time, in the same manner and as part of the tax. (b) If the withholding agent is the Government or any of its agencies, political subdivisions or instrumentalities, or a government owned or -controlled corporation, the employee thereof responsible for the withholding and remittance of the tax shall be personally liable for the additions to the tax prescribed herein. (c) The term "person", as used in this Chapter, includes an officer or employee of a corporation who as such officer, employee or member is under a duty to perform the act in respect of which the violation occurs. SEC. 248. Civil Penalties. — x x x[95] SEC. 255. Failure to File Return, Supply Correct and Accurate Information, Pay Tax, Withhold and Remit Tax and Refund Excess Taxes Withheld on Compensation. – Any person required under this Code or by rules and regulations promulgated thereunder to pay any tax, make a return, keep any record, or supply correct and accurate information, who willfully fails to pay such tax, make such return, keep such record, or supply such correct and accurate information, or withhold or remit taxes withheld, or refund excess taxes withheld on compensation, at the time or times required by law or rules and regulations shall, in addition to other penalties provided by law, upon conviction thereof, be punished by a fine of not less than Ten thousand pesos (P10,000) and suffer imprisonment of not less than one (l) year but not more than ten (10) years. CHAPTER Penalties Imposed on Public Officers III xxxx SEC. 272. Violation of Withholding Tax Provision. – Every officer or employee of the Government of the Republic of the Philippines or any of its agencies and instrumentalities, its political subdivisions, as well as governmentowned or -controlled corporations, including the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP), who, under the provisions of this Code or rules and regulations promulgated thereunder, is charged with the duty to deduct and withhold any internal revenue tax and to remit the same in accordance with the provisions of this Code and other laws is guilty of any offense hereinbelow specified shall, upon conviction for each act or omission be punished by a fine of not less than Five thousand pesos (P5,000) but not more than Fifty thousand pesos (P50,000) or suffer imprisonment of not less than six (6) months and one day (1) but not more than two (2) years, or both: (a) Failing or causing the failure to deduct and withhold any internal revenue tax under any of the withholding tax laws and implementing rules and regulations; SEC. 249. Interest. – x x x[96] xxxx (b) Failing or causing the failure to remit taxes deducted and withheld within the time prescribed by law, and implementing rules and regulations; and (c) Failing or causing the failure to file return or statement within the time prescribed, o rendering or furnishing a false or fraudulent return or statement required under the withholding tax laws and rules and regulations. [98] 1. 2. Based on the foregoing, and similar to Sections III and IV of the assailed RMO, the Court finds that Section VII thereof was issued in accordance with the provisions of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, and RR No. 2-98. For easy reference, Section VII of RMO No. 23-2014 states: VII. PENALTY PROVISION In case of non-compliance with their obligation as withholding agents, the abovementioned persons shall be liable for the following sanctions: A. B. Failure to Collect and Remit Taxes (Section 251, NIRC) "Any person required to withhold, account for, and remit any tax imposed by this Code or who willfully fails to withhold such tax, or account for and remit such tax, or aids or abets in any manner to evade any such tax or the payment thereof, shall, in addition to other penalties provided for under this Chapter, be liable upon conviction to a penalty equal to the total amount of the tax not withheld, or not accounted for and remitted." Failure to File Return, Supply Correct and Accurate Information, Pay Tax Withhold and Remit Tax and Refund Excess Taxes Withheld on Compensation (Section 255, NIRC) "Any person required under this Code or by rules and regulations promulgated thereunder to pay any tax make a return, keep any record, or supply correct the accurate information, who willfully fails to pay such tax, make such return, keep such record, or supply correct and accurate information, or withhold or remit taxes withheld, or refund excess taxes withheld on compensation, at the time or times required by law or rules and regulations shall, in addition to other penalties provided by law, upon conviction thereof, be punished by a fine of not less than Ten thousand pesos (P10,000) and suffer imprisonment of not less than one (1) year but not more than ten (10) years. Any person who attempts to make it appear for any reason that he or another has in fact filed a return or statement, or actually files a return or statement and subsequently withdraws the same return or statement after securing the official receiving seal or stamp of receipt of internal revenue office wherein the same was actually filed shall, upon conviction therefor, be punished by a fine of not less than Ten thousand pesos (P10,000) but not more than Twenty thousand pesos (P20,000) and suffer imprisonment of not less than one (1) year but not more than three (3) years." C. 3. Failing or causing the failure to deduct and withhold any internal revenue tax under any of the withholding tax laws and implementing rules and regulations; or Failing or causing the failure to remit taxes deducted and withheld within the time prescribed by law, and implementing rules and regulations; or Failing or causing the failure to file return or statement within the time prescribed, or rendering or furnishing a false or fraudulent return or statement required under the withholding tax laws and rules and regulations." All revenue officials and employees concerned shall take measures to ensure the full enforcement of the provisions of this Order and in case of any violation thereof, shall commence the appropriate legal action against the erring withholding agent. Verily, tested against the provisions of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, Section VII of RMO No. 23-2014 does not define a crime and prescribe a penalty therefor. Section VII simply mirrors the relevant provisions of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, on the penalties for the failure of the withholding agent to withhold and remit the correct amount of taxes, as implemented by RR No. 2-98. However, with respect to Section VI of the assailed RMO, the Court finds that the CIR overstepped the boundaries of its authority to interpret existing provisions of the NIRC of 1997, as amended. Section VI of RMO No. 23-2014 reads: VI. PERSONS RESPONSIBLE FOR WITHHOLDING The following officials are duty bound to deduct, withhold and remit taxes: a) For Office of the Provincial Government-province- the Chief Accountant, Provincial Treasurer and the Governor; b) For Office of the City Government-cities- the Chief Accountant, City Treasurer and the City Mayor; c) For Office of the Municipal Government-municipalities- the Chief Accountant, Municipal Treasurer and the Mayor; d) Office of the Barangay-Barangay Treasurer and Barangay Captain Violation of Withholding Tax Provisions (Section 272, NIRC) "Every officer or employee of the Government of the Republic of the Philippines or any of its agencies and instrumentalities, its political subdivisions, as well as government-owned or controlled corporations, including the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP), who is charged with the duty to deduct and withhold any internal revenue tax and to remit the same is guilty of any offense herein below specified shall, upon conviction for each act or omission be punished by a fine of not less than Five thousand pesos (P5,000) but not more than Fifty thousand pesos (P50,000) or suffer imprisonment of not less than six (6) months and one (1) day but not more than two (2) years, or both: e) For NGAs, GOCCs and other Government Offices, the Chief Accountant and the Head of Office or the Official holding the highest position (such as the President, Chief Executive Officer, Governor, General Manager). To recall, the Government of the Philippines, or any political subdivision or agency thereof, or any GOCC, as an employer, is constituted by law as the withholding agent, mandated to deduct, withhold and remit the correct amount of taxes on the compensation income received by its employees. In relation thereto, Section 82 of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, states that the return of the amount deducted and withheld upon any wage paid to government employees shall be made by the officer or employee having control of the payments or by any officer or employee duly designated for such purpose. [99] Consequently, RR No. 2-98 identifies the Provincial Treasurer in provinces, the City Treasurer in cities, the Municipal Treasurer in municipalities, Barangay Treasurer in barangays, Treasurers of government-owned or -controlled corporations (GOCCs), and the Chief Accountant or any person holding similar position and performing similar function in national government offices, as persons required to deduct and withhold the appropriate taxes on the income payments made by the government.[100] However, nowhere in the NIRC of 1997, as amended, or in RR No. 2-98, as amended, would one find the Provincial Governor, Mayor, Barangay Captain and the Head of Government Office or the "Official holding the highest position (such as the President, Chief Executive Officer, Governor, General Manager)" in an Agency or GOCC as one of the officials required to deduct, withhold and remit the correct amount of withholding taxes. The CIR, in imposing upon these officials the obligation not found in law nor in the implementing rules, did not merely issue an interpretative rule designed to provide guidelines to the law which it is in charge of enforcing; but instead, supplanted details thereon — a power duly vested by law only to respondent Secretary of Finance under Section 244 of the NIRC of 1997, as amended. Moreover, respondents' allusion to previous issuances of the Secretary of Finance designating the Governor in provinces, the City Mayor in cities, the Municipal Mayor in municipalities, the Barangay Captain in barangays, and the Head of Office (official holding the highest position) in departments, bureaus, agencies, instrumentalities, government-owned or -controlled corporations, and other government offices, as officers required to deduct and withhold,[101] is bereft of legal basis. Since the 1977 NIRC and Executive Order No. 651, which allegedly breathed life to these issuances, have already been repealed with the enactment of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, and RR No. 2-98, these previous issuances of the Secretary of Finance have ceased to have the force and effect of law. Accordingly, the Court finds that the CIR gravely abused its discretion in issuing Section VI of RMO No. 23-2014 insofar as it includes the Governor, City Mayor, Municipal Mayor, Barangay Captain, and Heads of Office in agencies, GOCCs, and other government offices, as persons required to withhold and remit withholding taxes, as they are not among those officials designated by the 1997 NIRC, as amended, and its implementing rules. Petition for Mandamus is moot and academic. As regards the prayer for the issuance of a writ of mandamus to compel respondents to increase the P30,000.00 non-taxable income ceiling, the same has already been rendered moot and academic due to the enactment of RA No. 10653.[102] The Court takes judicial notice of RA No. 10653, which was signed into law on February 12, 2015, which increased the income tax exemption for 13th month pay and other benefits, under Section 32(B)(7)(e) of the NIRC of 1997, as amended, from P30,000.00 to P82,000.00.[103] Said law also states that every three (3) years after the effectivity of said Act, the President of the Philippines shall adjust the amount stated therein to its present value using the Consumer Price Index, as published by the National Statistics Office. [104] Recently, RA No. 10963,[105] otherwise known as the "Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion (TRAIN)" Act, further increased the income tax exemption for 13th month pay and other benefits to P90,000.00.[106] A case is considered moot and academic if it ceases to present a justiciable controversy by virtue of supervening events, so that an adjudication of the case or a declaration on the issue would be of no practical value or use. Courts generally decline jurisdiction over such case or dismiss it on the ground of mootness. [107] With the enactment of RA Nos. 10653 and 10963, which not only increased the tax exemption ceiling for 13th month pay and other benefits, as petitioners prayed, but also conferred upon the President the power to adjust said amount, a supervening event has transpired that rendered the resolution of the issue on whether mandamus lies against respondents, of no practical value. Accordingly, the petition for mandamus should be dismissed for being moot and academic. As a final point, the Court cannot turn a blind eye to the adverse effects of this Decision on ordinary government employees, including petitioners herein, who relied in good faith on the belief that the appropriate taxes on all the income they receive from their respective employers are withheld and paid. Nor does the Court ignore the situation of the relevant officers of the different departments of government that had believed, in good faith, that there was no need to withhold the taxes due on the compensation received by said ordinary government employees. Thus, as a measure of equity and compassionate social justice, the Court deems it proper to clarify and declare, pro hac vice, that its ruling on the validity of Sections III and IV of the assailed RMO is to be given only prospective effect.[108] WHEREFORE, premises considered, the Petitions and Petitions-in Interventions are PARTIALLY GRANTED. Section VI of Revenue Memorandum Order No. 23-2014 is DECLARED null and void insofar as it names the Governor, City Mayor, Municipal Mayor, Barangay Captain, and Heads of Office in government agencies, government-owned or -controlled corporations, and other government offices, as persons required to withhold and remit withholding taxes. Sections III, IV and VII of RMO No. 23-2014 are DECLARED valid inasmuch as they merely mirror the provisions of the National Internal Revenue Code of 1997, as amended. However, the Court cannot rule on petitioners' claims of exemption from withholding tax on compensation income because these involve issues that are essentially factual or evidentiary in nature, which must be raised in the appropriate administrative and/or judicial proceeding. The Court's Decision upholding the validity of Sections III and IV of the assailed RMO is to be applied only prospectively. Finally, the Petition for Mandamus in G.R. No. 213446 is hereby DENIED on the ground of mootness. SO ORDERED. Less: Personal Exemption .............................. Amount subject to tax ....................................... 2,500.00 P29,317.66 1950: G.R. No. L-12954 February 28, 1961 COLLECTOR OF INTERNAL REVENUE, petitioner, vs. ARTHUR HENDERSON, respondent. February 28, 1961 ARTHUR HENDERSON, petitioner, vs. COLLECTOR OF INTERNAL REVENUE, respondent. PADILLA, J.: The spouses Arthur Henderson and Marie B. Henderson (later referred to as the taxpayers) filed with the Bureau of Internal Revenue returns of annual net income for the years 1948 to 1952, inclusive, where the following net incomes, personal exemptions and amounts subject to tax appear: Net Income ........................................................ Less: Personal Exemption .............................. Amount subject to tax ....................................... P32,605.83 Net Income ....................................................... Less: Personal Exemption .............................. Amount subject to tax ....................................... P36,780.11 3,000.00 P31,815.74 3,000.00 P29,605.83 1952: Office of the Solicitor General for petitioner. Formilleza & Latorre for respondent. These are petitioner filed by the Collector of Internal Revenue (G.R. No. L-12954) and by Arthur Henderson (G.R. No. L-13049) under the provisions of section 18, Republic Act No. 1125, for review of a judgment dated 26 June 1957 and a resolution dated 28 September 1957 rendered and adopted by the Court of Tax Appeals in Case No. 237. P34,815.74 1951: x---------------------------------------------------------x G.R. No. L-13049 Net Income ....................................................... Less: Personal Exemption .............................. Amount subject to tax ....................................... 3,000.00 P33,780.11 (Exhibits 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, A, F, J, N, R). In due time the taxpayers received from the Bureau of Internal Revenue assessment notices Nos. 15804-48, 25450-49, 15255-50, 25705-51 and 22527-52 and paid the amounts assessed as follows: 1948: 14 May 1949, O.R. No. 52991, Exhibit B ....……….. 1948: 12 September 1950, O.R. No. 160473, Exhibit B-1 . Net Income ....................................................... Less: Personal Exemption .............................. Amount subject to tax ....................................... P29,573.79 2,500.00 P27,073.79 P31,817.66 2,068.11 Total Paid ......................................................... P4,136.23 13 May 1950, O.R. No. 232366, Exhibit G ...........… P2,314.95 1949: 15 September 1950, O.R. No. 247918, Exhibit G-1 . 1949: Net Income ....................................................... P2,068.12 2,314.94 Total Paid ......................................................... P4,629.89 27 April 1951, O.R. No. 323173, Exhibit K ...………. P7,273.00 1950: 1951: Capital loss (no capital gain) ................... P3,248.84 Amount withheld from salary and paid by employer . P5,780.40 Undeclared bonus ...................………….. 3,857.75 15 May 1952, O.R. No. 33250, Exhibit O ................. 360.50 Rental allowance from A.I.U. ................... 1,800.00 15 August 1952, O.R. No. 383318, Exhibit O-1 ..….. Subsistence allowance from A.I.U. .…….. 361.20 6,051.30 Net income per investigation .........................................………... 14,958.09 Total Paid ......................................................... P6,502.10 Amount withheld from salary and paid by employer . P5,660.40 Amount of income subject to tax ..................................…………. 43,275.75 18 May 1953, O.R. No. 438026, Exhibit T ..………… 1,160.30 Tax due thereon ...............................................................………. P8,292.21 Less: Personal exemption ...............................................……….. 1952: 13 August 1953, O.R. No. 443483, Exhibit T-1 ...….. Total Paid ......................................................... 1,160.30 P7,981.00 On 28 November 1953, after investigation and verification, the Bureau of Internal Revenue reassessed the taxpayers' income for the years 1948 to 1952, inclusive, as follows: Less: tax already assessed & paid per OR Nos. 232366 & 247918 Net income per return ..................................……………………… P29,573.79 Add: Rent expense .........................................................…….. 7,200.00 Additional bonus for 1947 received May 13, 1948 .……… 6,500.00 Other income: Manager's residential expense (2/29/48 a/c/#4.51) 1,400.00 Manager's residential expense (refer to 1948 P & L) .. 1,849.32 Entrance fee — Marikina Gun & Country Club ..…….. 200.00 (Should be) ...................................................................... 3,662.32 1950: Rent, electricity, water allowances .......................……….. P43,189.47 Less: Personal exemption ...............................................……….. 3,000.00 Net taxable income ..........................................................……….. P40,189.47 Tax due thereon ...............................................................………. P10,296.00 Less: tax already paid per OR No. #323173 Deficiency tax due & assessable .................…………………….. 2,500.00 Net taxable income ..........................................................……… P44,223.11 Add: house rental allowance from AIU Tax due thereon ...............................................................……… P8,562.47 Net income per investigation .........................................………... 1949: Net income per return ..................................……………………… Add: disallowances — P31,817.66 8,373.73 Net income per investigation .........................................………... Less: Personal exemption ...............................................………. P4,426.24 P34,815.74 Add: P46,723.11 4,136.23 4,629.89 P3,662.23 Net income per investigation .........................................………... Less: Amount of tax already paid per OR #52991 & 160473 ..……………………………………………………… Deficiency tax still due & assessable ............................ 2,500.00 Deficiency tax due ............................................................………. Net income per return ..................................……………………… 1948: P46,775.75 7,273.00 P3,023.00 1951: Net income per return ..................................……………………… P32,605.83 5,782.91 P83,388.74 Less: Personal exemption ...............................................……….. 3,000.00 Amount of income subject to tax ..................................………….. P35,388.74 Tax due thereon ...............................................................………. P 8,560.00 Less: tax already assessed and paid per O.R. Nos. A33250 & 383318 .......................……………………………………… Deficiency tax due .................………………………………………. 6,502.00 P2,058.00 1952: Net income per return ..................................……………………… P36,780.11 Add: Withholding tax paid by company ..................................... 600.00 Travelling allowances ....................................................... 3,247.40 Allowances for rent, telephone, water, electricity, etc. ..... 7,044.67 Net income per investigation .........................................………... P47,672.18 Less: Personal exemption ...............................................……….. 3,000.00 Net taxable income ..................................………………………… P44,672.18 Tax due thereon ...............................................................………. P12,089.00 Less: Tax already withheld Tax already paid per O.R. Nos. #438026, 443484 P5,660.40 2,320.60 Deficiency tax still due & collectible ...............................………… 7,981.00 P4,108.00 (Exhibits 2, 4, 6, 8, 10) and demanded payment of the deficiency taxes on or before 28 February 1954 with respect to those due for the years 1948, 1949, 1950 and 1952and on or before 15 February 1954 with respect to that due for the year 1951 (Exhibits B-2, H, L, P, S). In the foregoing assessments, the Bureau of Internal Revenue considered as part of their taxable income the taxpayer-husband's allowances for rental, residential expenses subsistence, water, electricity and telephone; bonus paid to him; withholding tax and entrance fee to the Marikina gun and Country Club paid by his employer for his account; and travelling allowance of his wife. On 26 and27 January 1954 the taxpayers asked for reconsideration of the foregoing assessment (pp. 29, 31, BIR rec.) and on 11 February 1954 and 28 February 1955 stated the grounds and reasons in support of their request for reconsideration (pp. 36-38, 62-66, BIR rec.). The claim that as regards the husband-taxpayer's allowances for rental and utilities such as water, electricity and telephone, he did not receive the money for said allowances, but that they levied in the apartment furnished and paid for by his employer for its convenience; that they had no choice but live in the said apartment furnished by his employer, otherwise they would have lived in a less expensive one; that as regards his allowances for rental of P7,200 and residential expenses of P1,400 and P1,849.32 in 1948, rental of P1,800 and subsistence of P6,051.50 (the latter merely consisting of allowances for rent and utilities such as light, water, telephone, etc.) in 1949 rental, electricity and water of P8,373.73 in 1950, rental of P5,782.91 in 1951 and rental, telephone, water, electricity, etc. of P7,044.67 in 1952, only the amount of P3,900 for each year, which is the amount they would have spent for rental of an apartment including utilities, should be taxed; that as regards the amount ofP200 representing entrance fee to the Marikina Gun and Country Club paid for him by his employer in 1948, the same should not be considered as part of their income for it was an expense of his employer and his membership therein was merely incidental to his duties of increasing and sustaining the business of his employer; and that as regards the wife-taxpayer's travelling allowance of P3,247.40 in 1952, it should not be considered as part of their income because she merely accompanied him in his business trip to New York as his secretary and, at the behest of her husband's employer, to study and look into the details of the plans and decorations of the building intended to be constructed by his employer in its property at Dewey Boulevard. On 15 and 27 February 1954, the taxpayers paid the deficiency taxes assessed under Official Receipts Nos. 451841, 451842, 451843, 451748 and 451844 (Exhibits C, I, M, Q, and Y). After hearing conducted by the Conference Staff of the Bureau of Internal Revenue on5 October 1954 (pp. 74-85, BIR rec.), on 27 May 1955the Staff recommended to the Collector of Internal Revenue that the assessments made on 28 November 1953 (Exhibits2, 4, 6, 8, 10) be sustained except that the amount of P200 as entrance fee to the Marikina Gun and Country Club paid for the husband-taxpayer's account by his employer in 1948 should not be considered as part of the taxpayers' taxable income for that year (pp. 95-107, BIR rec.). On 14 July 1955, in line with the recommendation of the Conference Staff, the Collector of Internal Revenue denied the taxpayers' request for reconsideration, except as regards the assessment of their income tax due for the year 1948, which was modified as follows: Net income per return Add: Rent expense P29,573.79 7,200.00 Additional bonus for 1947 received on May 13, 1948 Manager's residential expense (2/29/48 a/c #4.41) Manager's residential expense (1948 profit and loss) Net income per investigation Less: Personal exemption 6,500.00 Net taxable income Tax due thereon P44,023.11 P 8,506.47 Less; Amount already paid Deficiency tax still due 4,136.23 P 4,370.24 1,400.00 1,849.32 P46,523.11 2,500.00 and demanded payment of the deficiency taxes of P4,370.24for 1948, P3,662.23 for 1949, P3,023 for 1950, P2,058 for1951 and P4,108 for 1952, 5% surcharge and 1% monthly interest thereon from 1 March 1954 to the date of payment and P80 as administrative penalty for late payment to the City Treasurer of Manila not later than 31 July1955 (Exhibit 14). On 30 January 1956 the taxpayers again sought a reconsideration of the denial of their request for reconsideration and offered to settle the case on a more equitable basis by increasing the amount of the taxable portion of the husband-taxpayer's allowances for rental, etc. from P3,000 yearly to P4,800 yearly, which "is the value to the employee of the benefits he derived there from measured by what he had saved on account thereof 'in the ordinary course of his life ... for which he would have spent in any case'". The taxpayers also reiterated their previous stand regarding the transportation allowance of the wife-taxpayer of P3,247.40 in 1952 and requested the refund of the amounts of P3,477.18, P569.33,P1,294, P354 and P2,164, or a total of P7,858.51, (Exhibit Z). On 10 February 1956 the taxpayers again requested the Collector of Internal Revenue to refund to them the amounts allegedly paid in excess as income taxes for the years 1948 to 1952, inclusive (Exhibit Z-1). The Collector of Internal Revenue did not take any action on the taxpayers' request for refund. On 15 February 1956 the taxpayers filed in the Court of Tax Appeals a petition to review the decision of the Collector of Internal Revenue (C.T.A. Case No. 237). After hearing, on 26 June 1957 the Court rendered judgment holding "that the inherent nature of petitioner's(the husband-taxpayer) employment as president of the American International Underwriters as president of the American International Underwriters of the Philippines, Inc. does not require him to occupy the apartments supplied by his employer-corporation;" that, however, only the amount of P4,800 annually, the ratable value to him of the quarters furnished constitutes a part of taxable income; that since the taxpayers did not receive any benefit out of the P3,247.40 traveling expense allowance granted in 1952 to the wife-taxpayer and that she merely undertook the trip abroad at the behest of her husband's employer, the same could not be considered as income; and that even if it were considered as such, still it could not be subject to tax because it was deductible as travel expense; and ordering the Collector of Internal Revenue to refund to the taxpayers the amount of P5,109.33 with interest from 27 February 1954, without pronouncement as to costs. The taxpayers filed a motion for reconsideration claiming that the amount of P5,986.61 is the amount refundable to them because the amounts of P1,400 and P1,849.32 as manager's residential expenses in 1948 should not be included in their taxable net income for the reason that they are of the same nature as the rentals for the apartment, they being mainly expenses for utilities as light, water and telephone in the apartment furnished by the husband-taxpayer's employer. The Collector of Internal Revenue filed an opposition to their motion for reconsideration. He also filed a separate motion for reconsideration of the decision claiming that his assessment under review was correct and should have been affirmed. The taxpayers filed an opposition to this motion for reconsideration of the Collector of Internal Revenue; the latter, a reply thereto. On 28 September 1957 the Court denied both motions for reconsideration. On 7 October1957 the Collector of Internal Revenue filed a notice of appeal in the Court of Tax Appeals and on 21 October1957, within the extension of time previously granted by this Court, a petition for review (G.R. No. L-12954). On29 October 1957 the taxpayers filed a notice of appealin the Court of Tax Appeals and a petition for review in this Court (G.R. No. L-13049). The Collector of Internal Revenue had assigned the following errors allegedly committed by the Court of Tax Appeals: I. The Court of Tax Appeals erred in finding that the herein respondent did not have any choice in the selection of the living quarters occupied by him. II. The Court of Tax Appeals erred in not considering the fact that respondent is not a minor company official but the President of his employer-corporation, in the appreciation of respondent's alleged lack of choice in the matter of the selection of the quarters occupied by him. III. The Court of Tax Appeals erred in giving full weight and credence to respondent's allegation, a selfserving and unsupported declaration that the ratable value to him of the living quarters and subsistence allowance was only P400.00 a month. IV. The Court of Tax Appeals erred in holding that only the ratable value of P4,800.00 per annum, or P400.00 a month constitutes income to respondent. V. The Court of Tax Appeals erred in arbitrarily fixing the amount of P4,800.00 per annum, or P400.00 a month as the only amount taxable against respondent during the five tax years in question. VI. The Court of Tax Appeals erred in not finding that travelling allowance in the amount of P3,247.40 constituted income to respondent and, therefore, subject to the income tax. VII. The Court of Tax Appeals erred in ordering the refund of the sum of P5,109.33 with interest from February 17, 1954. (G.R. No. L-12954.) The taxpayers have assigned the following errors allegedly committed by the Court of Tax Appeals: I. The Court of Tax Appeals erred in its computation of the 1948 income tax and consequently in the amount that should be refunded for that year. II. The Court of Tax Appeals erred in denying our motion for reconsideration as contained in its resolution dated September 28, 1957. (G.R. No. L-13049.) The Government's appeal: The Collector of Internal Revenue raises questions of fact. He claims that the evidence is not sufficient to support the findings and conclusion of the Court of Tax Appeals that the quarters occupied by the taxpayers were not of their choice but that of the husband-taxpayer's employer; that it did not take into consideration the fact that the husband-taxpayer is not a mere minor company official, but the highest executive of his employercorporation; and that the wife-taxpayer's trip abroad in 1952 was not, as found by the Court, a business but a vacation trip. In Collector of Internal Revenue vs. Aznar, 56, Off. Gaz. 2386, this Court held that in petitions for review under section 18, Republic Act No. 1125, it may review the findings of fact of the Court of Tax Appeals. The determination of the main issue in the case requires a review of the evidence. Are the allowances for rental of the apartment furnished by the husband-taxpayer's employer-corporation, including utilities such as light, water, telephone, etc. and the allowance for travel expenses given by his employer-corporation to his wife in 1952 part of taxable income? Section 29, Commonwealth Act No. 466, National Internal Revenue Code, provides: "Gross income" includes gains, profits, and income derived from salaries, wages, or compensation for personal service of whatever kind and in whatever form paid, or from professions, vocations, trades, businesses, commerce, sales, or dealings in property, whether real or personal, growing out of the ownership or use of or interest in such property; also from interest, rents dividend, securities, or the transaction of any business carried on for gain or profit, or gains, profits, and income derived from any source whatever. (Emphasis ours.) The Court of Tax Appeals found that the husband-taxpayer "is the president of the American International Underwriters for the Philippines, Inc., a domestic corporation engaged in insurance business;" that the taxpayers "entertained officials, guests and customers of his employer-corporation, in apartments furnished by the latter and successively occupied by him as president thereof; that "In 1952, petitioner's wife, Mrs. Marie Henderson, upon request o Mr. C. V. Starr, chairman of the parent corporation of the American International Underwriters for the Philippines, Inc., undertook a trip to New York in connection with the purchase of a lot in Dewey Boulevard by petitioner's employer-corporation, the construction of a building thereon, the drawing of prospectus and plans for said building, and other related matters." Arthur H. Henderson testified that he is the President of American International Underwriters for the Philippines, Inc., which represents a group of American insurance companies engaged in the business of general insurance except life insurance; that he receives a basic annual salary of P30,000 and allowance for house rental and utilities like light, water, telephone, etc.; that he and his wife are childless and are the only two in the family; that during the years 1948 to 1952, they lived in apartments chosen by his employer; that from 1948 to the early part of 1950, they lived at the Embassy Apartments on Dakota Street, Manila, where they had a large sala, three bedrooms, dining room, two bathrooms, kitchen and a large porch, and from the early part of 1950 to 1952, they lived at the Rosaria Apartments on the same street where they had a kitchen, sala, dining room two bedrooms and bathroom; that despite the fact that they were the only two in the family, they had to live in apartments of the size beyond their personal needs because as president of the corporation, he and his wife had to entertain and put up houseguests; that during all those years of 1948 to 1952, inclusive, they entertained and put up houseguests of his company's officials, guests and customers such as the president of C, V. Starr & Company, Inc., who spent four weeks in his apartment, Thomas Cocklin, a lawyer from Washington, D.C., and Manuel Elizalde, a stockholder of AIUPI; that were he not required by his employer to live in those apartments furnished to him, he and his wife would have chosen an apartment only large enough for them and spend from P300 to P400 monthly for rental; that of the allowances granted to him, only the amount of P4,800 annually, the maximum they would have spent for rental, should be considered as taxable income and the excess treated as expense of the company; and that the trip to New York undertaken by his wife in 1952, for which she was granted by his employer-corporation travelling expense allowance of P3,247.40, was made at the behest of his employer to assist its architect in the preparation of the plans for a proposed building in Manila and procurement of supplies and materials for its use, hence the said amount should not be considered as part of taxable income. In support of his claim, letters written by his wife while in New York concerning the proposed building, inquiring about the progress made in the acquisition of the lot, and informing him of the wishes of Mr. C. V. Starr, chairman of the board of directors of the parent-corporation (Exhibits U-1, U-1-A, V, V-1 and W) and a letter written by the witness to Mr. C. V. Starr concerning the proposed building (Exhibits X, X-1) were presented in evidence. Mrs. Marie Henderson testified that for almost three years, she and her husband gave parties every Friday night at their apartment for about 18 to 20 people; that their guests were officials of her husband's employercorporation and other corporations; that during those parties movies for the entertainment of the guests were shown after dinner; that they also entertained during luncheons and breakfasts; that these involved and necessitated the services of additional servants; and that in 1952 she was asked by Mr. C. V. Starr to come to New York to take up problems concerning the proposed building and entertainment because her husband could not make the trip himself, and because "the woman of the family is closer to those problems." The evidence presented at the hearing of the case substantially supports the findings of the Court of Tax Appeals. The taxpayers are childless and are the only two in the family. The quarters, therefore, that they occupied at the Embassy Apartments consisting of a large sala, three bedrooms, dining room, two bathrooms, kitchen and a large porch, and at the Rosaria Apartments consisting of a kitchen, sala dining room, two bedrooms and a bathroom, exceeded their personal needs. But the exigencies of the husband-taxpayer's high executive position, not to mention social standing, demanded and compelled them to live in a more spacious and pretentious quarters like the ones they had occupied. Although entertaining and putting up houseguests and guests of the husband-taxpayer's employer-corporation were not his predominant occupation as president, yet he and his wife had to entertain and put up houseguests in their apartments. That is why his employercorporation had to grant him allowances for rental and utilities in addition to his annual basic salary to take care of those extra expenses for rental and utilities in excess of their personal needs. Hence, the fact that the taxpayers had to live or did not have to live in the apartments chosen by the husband-taxpayer's employercorporation is of no moment, for no part of the allowances in question redounded to their personal benefit or was retained by them. Their bills for rental and utilities were paid directly by the employer-corporation to the creditors (Exhibit AA to DDD, inclusive; pp. 104, 170-193, t.s.n.). Nevertheless, as correctly held by the Court of Tax Appeals, the taxpayers are entitled only to a ratable value of the allowances in question, and only the amount of P4,800 annually, the reasonable amount they would have spent for house rental and utilities such as light, water, telephone, etc., should be the amount subject to tax, and the excess considered as expenses of the corporation. Likewise, the findings of the Court of Tax Appeals that the wife-taxpayer had to make the trip to New York at the behest of her husband's employer-corporation to help in drawing up the plans and specifications of a proposed building, is also supported by the evidence. The parts of the letters written by the wife-taxpayer to her husband while in New York and the letter written by the husband-taxpayer to Mr. C. V. Starr support the said findings (Exhibits U-2, V-1, W-1, X). No part of the allowance for travelling expenses redounded to the benefit of the taxpayers. Neither was a part thereof retained by them. The fact that she had herself operated on for tumors while in New York was but incidental to her stay there and she must have merely taken advantage of her presence in that city to undergo the operation. The taxpayers' appeal: The taxpayers claim that the Court of Tax Appeals erred in considering the amounts of P1,400 and P1,849.32, or a total of P3,249.32, for "manager's residential expense" in 1948 as taxable income despite the fact "that they were of the same nature as the rentals for the apartment, they being expenses for utilities, such as light, water and telephone necessarily incidental to the apartment furnished to him by his employer." Mrs. Crescencia Perez Ramos, an examiner of the Bureau of Internal Revenue who examined the books of account of the American International Underwriters for the Philippines, Inc., testified that he total amount of P3,249.32 was reflected in its books as "living expenses of Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Henderson in the quarters they occupied in 1948;" and that "the amount of P1,400 was included as manager's residential expense while the amount of P1,849.32 was entered as profit and loss account." Buenaventura Loberiza, acting head of the accounting department of the American International Underwriters for the Philippines, Inc., testified that rentals, utilities, water, telephone and electric bills of executives of the corporation were entered in the books of account as "subsistence allowances and expenses;" that there was a separate account for salaries and wages of employees and officers; and that expenses for rentals and other utilities were not charged to salary accounts. The taxpayers' claim is supported by the evidence. The total amount of P3,249.32 "for manager's residential expense" in 1948 should be treated as rentals for apartments and utilities and should not form part of the ratable value subject to tax. The computation made by the taxpayers is correct. Adding to the amount of P29,573.79, their net income per return, the amount of P6,500, the bonus received in 1948, and P4,800, the taxable ratable value of the allowances, brings up their gross income to P40,873.79. Deducting therefrom the amount of P2,500 for personal exemption, the amount of P38,373.79 is the amount subject to income tax. The income tax due on this amount is P6,957.19 only. Deducting the amount of income tax due, P6,957.19, from the amount already paid, P8,562.47 (Exhibits B, B-1, C), the amount of P1,605.28 is the amount refundable to the taxpayers. Add this amount to P563.33, P1,294.00, P354.00 and P2,154.00, refundable to the taxpayers for 1949, 1950, 1951 and 1952 and the total is P5,986.61. The judgment under review is modified as above indicated. The Collector of Internal Revenue is ordered to refund to the taxpayers the sum of P5,986.61, without pronouncement as to costs. Notwithstanding the aforesaid 5% franchise tax imposed, the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) issued several assessments against PAGCOR for alleged deficiency value-added tax (VAT), final withholding tax on fringe benefits, and expanded withholding tax, as follows: G.R. No. 177387 ASSESSMENT November 9, 2016 DATE ISSUED PERIOD COVERED November 14, 2002 1996/1997/1998 TOTAL AMOUNT DUE (inclusive of interest, surcharge and compromise penalty) ₱4,078,476,977.26 November 25, 2002 1999 ₱6,678,346,966.49 March 18, 2003 2000 ₱2,953,321,685.92 TOTAL ₱13,710,145,629.67 COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE, Petitioner vs. SECRET ARY OF JUSTICE, and PHILIPPINE AMUSEMENT AND GAMING CORPORATION, Respondents DECISION No. 33-1996/1997/1998 (for deficiency VAT) No. 33-99 (for deficiency VAT, final withholding tax on fringe benefits, and expanded withholding tax) No. 33-2000 (for deficiency VAT and final withholding tax on fringe benefits) 5 BERSAMIN, J.: Petitioner Commissioner of Internal Revenue (CIR) commenced this special civil action for certiorari to annul the December 22, 2006 resolution and the March 12, 2007 resolution, both issued by the Secretary of Justice in OSJ Case No. 2004-1, alleging that respondent Secretary of Justice acted without or in excess of his jurisdiction, or in grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction. 1 2 6 7 The dispositive portion of the assailed December 22, 2006 resolution states: WHEREFORE, premises considered, PAGCOR is declared exempt from payment [oil all taxes, save for the franchise tax as provided for under Section 13 of PD 1869, as amended, the presidential issuance not having been expressly repealed by RA 7716. On December 18, 2002, PAGCOR filed a letter-protest with the BIR against Assessment Notice No. 331996/1997 /1998 and Assessment Notice No. 33-99. 8 3 while the March 12, 2007 resolution denied the CIR’s motion for reconsideration of the December 22, 2006 resolution. On March 31, 2003, PAGCOR filed a letter-protest against Assessment Notice No. 33-2000, in which it reiterated the asse1iions made in its December 18, 2002 letter-protest. 9 In reply to both letters-protest, the BIR requested PAGCOR to submit additional documents to enable the conduct of the reinvestigation. Antecedents 10 Respondent Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation (PAGCOR) has operated under a legislative franchise granted by Presidential Decree No. 1869 (P.O. No. 1869), its Charter, whose Section 13(2) provides that: 4 The CIR did not act on PAGCOR’s letter-protest against Assessment Notice No. 33-1996/1997 /1998 and Assessment Notice No. 33-99 within the 180-day period from the latter's submission of additional documents. Hence, PAGCOR filed an appeal with the Secretary of Justice on January 5, 2004 relative to Assessment Notice No. 33-1996/1997 /1998 and Assessment Notice No. 33-99. 11 12 (2) Income and other Taxes - (a) Franchise Holder: No tax of any kind or form, income or otherwise, as well as fees, charges or levies of whatever nature, whether National or Local, shall he assessed and collected under this Franchise from the Corporation; nor shall any form of tax or charge attach in any way to the earnings of the Corporation, except a Franchise Tax of five percent (S(X1) of the gross revenue or earnings derived by the Corporation from its operation under this Franchise. Such tax shall be due and payable quarterly to the National Government and shall be in lieu of all kinds of taxes, levies, fees or assessments of any kind, nature or description, levied, established or collected by any municipal, provincial or national government authority. (bold emphasis supplied) Meanwhile, in response to PAGCOR’s letter-protest dated March 31, 2003, BIR Regional Director Teodorica Arcega issued a letter dated December 15, 2003 reiterating the assessment for deficiency VAT for taxable year 2000, stating thusly: 13 In a memorandum to the Regional Director dated December 15, 2003 the Chief Legal Division, this Region, confirmed the taxability of PAGCOR under Section 108(A) of the 1997 Tax Code, as amended, effective Jan. 1, 1996 (VAT Review Committee Ruling No. 041-2001 ). In view of the confirmation of the Legal Division we hereby reiterate the assessments forwarded to your office under Final Assessment No. 33-2000 dated March 18, 2003 amounting to ₱2,097,426,943.00. However, the BIR only recomputed the deficiency final withholding tax on fringe benefits and expanded withholding tax, and reduced the assessments to ₱l2,212, 199.85 and ₱6,959,525. l0, respectively. RESPONDENT SECRETARY OF JUSTICE ACTED WITHOUT OR IN EXCESS OF HIS JURISDICTION AND GRAVELY ABUSED HIS DISCRETION IN ABSOLVING PAGCOR OF ITS DUTY AND RESPONSIBILITY AS WITHHOLDING AGENT TO WITHHOLD AND REMIT FRINGE BENEFITS TAX, FINAL WITHHOLDING TAX AND EXPANDED WITHHOLDING TAX. 21 14 PAGCOR elevated its protest against Assessment Notice No. 33-2000 to the CIR, but the 180-day period prescribed by law also lapsed without any action on the part of the CIR. Consequently, on August 4, 2004, PAGCOR brought another appeal to the Secretary of Justice covering Assessment Notice No. 33-2000. 15 Otherwise put, the issues to be resolved are: (1) whether or not the Secretary of Justice has jurisdiction to review the disputed assessments; (2) whether or not PAGCOR is liable for the payment of VAT; and (3) whether or not P AGCOR is liable for the payment of withholding taxes. 16 Ruling The Secretary of Justice consolidated PAGCOR's two appeals. The petition for certiorari is partly granted. After the parties traded pleadings, the Secretary of Justice summoned them to a preliminary conference to discuss, inter alia, any possible settlement or compromise. When no amicable settlement was reached, the consolidated appeals were considered submitted for resolution. 17 1. The Secretary of Justice has no jurisdiction to review the disputed assessments 18 On December 22, 2006, Secretary of Justice Raul M. Gonzales rendered the first assailed resolution declaring PAGCOR exempt from the payment of all taxes except the 5% franchise tax provided in its Charter. 19 On March 12, 2007, Secretary Gonzales issued the second assailed resolution denying the CIR's motion for reconsideration. 20 Hence, this special civil action for certiorari. Issues The grounds for the petition for certiorari are as follows: I RESPONDENT SECRETARY OF JUSTICE ACTED WITHOUT OR IN EXCESS OF HIS JURISDICTION AND GRAVELY ABUSED HIS DISCRETION IN ASSUMING JURISDICTION OVER THE PETITION ON DISPUTED TAX ASSESSMENTS FILED BY RESPONDENT PAGCOR. II RESPONDENT SECRETARY OF JUSTICE ACTED WITHOUT OR IN EXCESS OF HIS JURISDICTION AND GRAVELY ABUSED HIS DISCRETION IN HOLDING THAT R.A. NO. 7716 (VAT LAW) DID NOT REPEAL P.D. NO. 1869 (CHARTER OF PAGCOR); HENCE, PAGCOR HAS NOT BECOME LIABLE FOR THE PAYMENT OF THE 10% VAT IN LIEU OF THE 5% FRANCHISE TAX. III The petitioner contends that it is the Court of Tax Appeals (CTA), not the Secretary of Justice, that has the exclusive appellate jurisdiction in this case, pursuant to Section 7(1) of Republic Act No. 1125 (R.A. No. 1125), which grants the CTA the exclusive appellate jurisdiction to review, among others, the decisions of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue "in cases involving disputed assessments, refunds of internal revenue taxes, fees or other charges, penalties imposed in relation thereto, or other matters arising under the National Internal Revenue Code (NIRC) or other law or part of law administered by the Bureau of Internal Revenue." PAGCOR counters, however, that it is the Secretary of Justice who should adjudicate the dispute by virtue of Chapter 14 of the Revised Administrative Code of 1987, which provides: CHAPTER 14. CONTROVERSIES AMONG GOVERNMENT OFFICES AND CORPORATIONS. SEC. 66. How settled. - All disputes/claims and controversies, solely between or among the departments, bureaus, offices, agencies and instrumentalities of the National Government, including government-owned and controlled corporations, such as those arising from the interpretation and application of statues, contracts or agreements shall be administratively settled or adjudicated in the manner provided for in this Chapter. This Chapter shall, however, not apply to disputes involving the Congress, the Supreme Court, the Constitutional Commission and local governments. SEC. 67. Disputes Involving Questions of Law. - All cases involving only questions of law shall be submitted to and settled or adjudicated by the Secretary of Justice as Attorney-General of the National Government and as ex-officio legal adviser of all government-owned or controlled corporations. His ruling or decision thereon shall be conclusive and binding on all the parties concerned. SEC. 68. Disputes Involving Questions of Fact and Law. – Cases involving mixed questions of law and of fact or only factual issues shall be submitted to and settled or adjudicated by: (1) The Solicitor General, if the dispute, claim or controversy involves only departments, bureaus, offices and other agencies of the National Government as well as government-owned or controlled corporations or entities of whom he is the principal law officer or general counsel; and the doctrine of stare decisis required him to adhere to the ruling of the Court, which by tradition and conformably with our system of judicial administration speaks the last word on what the law is, and stands as the final arbiter of any justiciable controversy. In other words, there is only one Supreme Court from whose decisions all other courts and everyone else should take their bearings. 27 (2) The Secretary of Justice, in all other cases not falling under paragraph (1). Although acknowledging the validity of the petitioner's contention, the Secretary of Justice still resolved the disputed assessments on the basis that the prevailing doctrine at the time of the filing of the petitions in the Department of Justice (DOJ) on January 5, 2004 was that enunciated in Development Bank of the Philippines v. Court of Appeals, whereby the Court ruled that: 22 x x x (T)here is an "irreconcilable repugnancy x x between Section 7(2) of R.A. NO. 1125 and P.D. No. 242," and hence, that the latter enactment (P.O. No. 242), being the latest expression of the legislative will, should prevail over the earlier. Later on, the Court reversed itself in Philippine National Oil Company v. Court of Appeals, and held as follows: 23 Following the rule on statutory construction involving a general and a special law previously discussed, then P.O. No. 242 should not affect R.A. No. 1125. R.A. No. 1125, specifically Section 7 thereof on the jurisdiction of the CTA, constitutes an exception to P.O. No. 242. Disputes, claims and controversies, falling under Section 7 of R.A. No. 1125, even though solely among government offices, agencies, and instrumentalities, including government-owned and controlled corporations, remain in the exclusive appellate jurisdiction of the CTA. Such a construction resolves the alleged inconsistency or conflict between the two statutes, x x x. Despite the shift in the construction of P.D. No. 242 in relation to R.A. No. 1125, the Secretary of Justice still resolved PAGCOR's petitions on the merits, stating that: While this ruling (DBP) has been superseded by the ruling in Philippine National Oil Company vs. CA, in view of the prospective application of the PNOC ruling, we (the DOJ) are of the view that this Office can continue to assume jurisdiction over this case which was filed and has been pending with this Office since January 5, 2004 and rule on the merits of the case. Nonetheless, the Secretary of Justice should not be taken to task for initially entertaining the petitions considering that the prevailing interpretation of the law on jurisdiction at the time of their filing was that he had jurisdiction. Neither should PAGCOR to blame in bringing its appeal to the DOJ on January 5, 2004 and August 4, 2004 because the prevailing rule then was the interpretation in Development Bank of the Philippines v. Court of Appeals. The emergence of the later ruling was beyond PAGCOR's control. Accordingly, the lapse of the period within which to appeal the disputed assessments to the CTA could not be taken against P AGCOR. While a judicial interpretation becomes a part of the law as of the date that the law was originally passed, the reversal of the interpretation cannot be given retroactive effect to the prejudice of parties who may have relied on the first interpretation. 28 The Court now undertakes to settle the controversy because of the urgent need to promptly decide it. We cannot lose sight of the fact that PAGCOR is among the most prolific income-generating institutions that contribute immensely to the country's developing economy. Any controversy involving PAGCOR should be resolved expeditiously considering the underlying public interest in the matter at hand. To dismiss the petitions in order to have PAGCOR bring a similar petition in the CTA would not serve the interest of justice. On previous occasions, the Court has overruled the defense of jurisdiction in the interest of public welfare and for the advancement of public policy whenever, as in this case, an extraordinary situation existed. 29 30 2. PAGCOR is exempt from payment of VAT The CIR insists that under VAT Ruling No. 04-96 (dated May 14, 1996), VAT Ruling No. 030-99 (dated March 18, 1999), and VAT Ruling No. 067-01 (dated October 8, 2001), R.A. No. 7716 has expressly repealed, amended, or withdrawn the 5% franchise tax provision in PAGCOR's Charter; hence, PAGCOR was liable for the 10% VAT. 31 32 The relevant provisions of R.A. No. 7716 on which the insistence has been anchored are the following: 24 SEC. 3. Section 102 of the National Internal Revenue Code, as amended, is hereby further amended to read as follows: We disagree with the action of the Secretary of Justice. PAGCOR filed its appeals in the DOI on January 5, 2004 and August 4, 2004. Philippine National Oil Company v. Court of Appeals was promulgated on April 26, 2006. The Secretary of Justice resolved the petitions on December 22, 2006. Under the circumstances, the Secretary of Justice had ample opportunity to abide by the prevailing rule and should have referred the case to the CTA because judicial decisions applying or interpreting the law formed part of the legal system of the country, and are for that reason to be held in obedience by all, including the Secretary of Justice and his Department. Upon becoming aware of the new proper construction of P.D. No. 242 in relation to R.A. No. 1125 pronounced in Philippine National Oil Company v. Court of Appeals, therefore, the Secretary of Justice should have desisted from dealing with the petitions, and referred them to the CTA, instead of insisting on exercising jurisdiction thereon. Therein lay the grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction on the part of the Secretary of Justice, for he thereby acted arbitrarily and capriciously in ignoring the pronouncement in Philippine National Oil Company v. Court of Appeals. Indeed, 25 "SEC. l 02. Value-added tax on sale of services and use or lease of properties. - (a) Rate and base of tax. There shall be levied, assessed and collected, a value-added tax equivalent to 10% of gross receipts derived from the sale or exchange of services, including the use or lease of properties. 26 "The phrase 'sale or exchange of services' means the performance of all kinds of service in the Philippines for others for a fee, remuneration or consideration, including x x x service of franchise grantees of telephone and telegraph, radio and television broadcasting and all other franchise grantees except those under Section 117 of this Code; x x x" SEC. 12. Section 117 of the National Internal revenue Code, as amended, is hereby further amended further to read as follows: "SEC.117. Tax on Franchises. - Any provision of general or special law to the contrary notwithstanding, there shall be levied, assessed and collected in respect to all franchises on electric, gas and water utilities a tax of two percent (2%) on the gross receipts derived from the business covered by the law granting the franchise. x x x" Although Section 3 of R.A. No. 7716 imposes 10% VAT on the sale or exchange of services, including the use or lease of properties, the provision also considers transactions that are subject to 0% VAT. On the other hand, Section 4 of R.A. No. 7716 enumerates the transactions exempt from VAT, viz.: 35 SEC. 4. Section 103 of the National Internal Revenue Code, as amended, is hereby further amended to read as follows: "SEC.103. Exempt transactions. - The following shall he exempt from the value-added tax: SEC. 20. Repealing Clauses. - The provisions of any special law relative to the rate of franchise taxes are hereby expressly repealed.x x x The CIR argues that PAGCOR' s gambling operations are embraced under the phrase sale or exchange of services, including the use or lease of properties; that such operations are not among those expressly exempted from the 10% VAT under Section 3 of R.A. No. 7716; and that the legislative purpose to withdraw PAGCOR's 5% franchise tax was manifested by the language used in Section 20 of R.A. No.7716. xxxx "(q) Transactions which are exempt under special laws, except those granted under Presidential Decree Nos. 66, 529, 972, 1491, and 1590, and nonelectric cooperatives under republic Act No. 6938, or international agreements to which the Philippines is a signatory; x x x x" (bold emphasis supplied.) The CIR' s arguments lack merit. Firstly, a basic rule in statutory construction is that a special law cannot be repealed or modified by a subsequently enacted general law in the absence of any express provision in the latter law to that effect. A special law must be interpreted to constitute an exception to the general law in the absence of special circumstances warranting a contrary conclusion. R.A. No. 7716, a general law, did not provide for the express repeal of PAGCOR's Charter, which is a special law; hence, the general repealing clause under Section 20 of R.A. No. 7716 must pertain only to franchises of electric, gas, and water utilities, while the term other franchises in Section 102 of the NIRC should refer only to transport, communications and utilities, exclusive of PAGCOR's casino operations. 33 Secondly, R.A. No. 7716 indicates that Congress has not intended to repeal PAGCOR's privilege to enjoy the 5% franchise tax in lieu of all other taxes. A contrary construction would be unwarranted and myopic nitpicking. In this regard, we should follow the following apt reminder uttered in Fort Bonifacio Development Corporation v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue: Anent the effect of R.A. No. 7716 on franchises, the Court has observed in Tolentino v. The Secretary of Finance that: 36 Among the provisions of the NIRC amended is §103, which originally read: §103. Exempt transactions.-The following shall be exempt from the value-added tax: .... (q) Transactions which are exempt under special laws or international agreements to which the Philippines is a signatory. 34 A law must not be read in truncated parts: its provisions must be read in relation to the whole law. It is the cardinal rule in statutory construction that a statute’s clauses and phrases must not be taken as detached and isolated expressions but the whole and every part thereof must be considered in fixing the meaning of any of its parts in order to produce a harmonious whole. Every part of the statute must be interpreted with reference to the context, i.e., that every part of the statute must be considered together with other parts of the statute and kept subservient to the general intent of the whole enactment. In constructing a statute courts have to take the thought conveyed by the statute as a whole: construe the constituent parts together; ascertain the legislative intent from the whole act; consider each and every provision thereof in the light of the general purpose of the statute; and endeavor to make every part effective, harmonious and sensible. Among the transactions exempted from the VAT were those of PAL because it was exempted under its franchise (P.D. No. 1590) from the payment of all "other taxes ... now or in the near future," in consideration of the payment by it either of the corporate income tax or a franchise tax of 2%. As a result of its amendment by Republic Act No. 7716, §103 of the NIRC now provides: §103. Exempt transactions.-The following shall be exempt from the value-added tax: …….. (q) Transactions which are exempt under special laws, except those granted under Presidential Decree Nos. 66, 529, 972, 1491, 1590 ..... The effect of the amendment is to remove the exemption granted to PAL, as far as the VAT is concerned. xxxx x x x Republic Act No. 7716 expressly amends PAL's franchise (P.D. No. 1590) by specifically excepting from the grant of exemptions from the VAT PAL's exemption under P.D. No. 1590. This is within the power of Congress to do under Art. XII, § 11 of the Constitution, which provides that the grant of a franchise for the operation of a public utility is subject to amendment, alteration or repeal by Congress when the common good so requires. 37 Unlike the case of PAL, however, R.A. No. 7716 does not specifically exclude PAGCOR's exemption under P.D. No. 1869 from the grant of exemptions from VAT; hence, the petitioner's contention that R.A. No. 7716 expressly amended PAGCOR's franchise has no leg to stand on. Moreover, PAGCOR's exemption from VAT, whether under R.A. No. 7716 or its amendments, has been settled in Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation (PAGCOR) v. The Bureau of Internal Revenue, whereby the Court, citing Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Acesite (Philippines) Hotel Corporation, has declared: As pointed out by petitioner, although R.A. No. 9337 introduced amendments to Section 108 of R.A. No. 8424 by imposing VAT on other services not previously covered, it did not amend the portion of Section 108 (B) (3) that subjects to zero percent rate services performed by VAT-registered persons to persons or entities whose exemption under special laws or international agreements to which the Philippines is a signatory effectively subjects the supply of such services to 0% rate. Petitioner's exemption from VAT under Section 108 (B) (3) of R.A. No. 8424 has been thoroughly and extensively discussed in Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Acesite (Philippines) Hotel Corporation. x x x The Court ruled that PAGCOR and Acesite were both exempt from paying VAT, thus: xxxx PAGCOR is exempt from payment of indirect taxes 38 39 Petitioner is exempt from the payment of VAT, because PAGCORs charter, P.D. No. 1869, is a special law that grants petitioner exemption from taxes. Moreover, the exemption of PAGCOR from VAT is supported by Section 6 of R.A. No. 9337, which retained Section 108 (B) (3) of R.A. No. 8424, thus: [R.A. No. 9337], SEC. 6. Section 108 of the same Code (R.A. No. 8424), as amended, is hereby further amended to read as follows: SEC. 108. Value-Added Tax on Sale of Services and Use or Lease of Properties. (A) Rate and Base of Tax. There shall be levied, assessed and collected, a value-added tax equivalent to ten percent (10%) of gross receipts derived from the sale or exchange of services, including the use or lease of properties: x x x xxxx (B) Transactions Subject to Zero Percent (0%) Rate. The following services performed in the Philippines by VAT-registered persons shall be subject to zero percent (0%) rate; xxxx (3) Services rendered to persons or entities whose exemption under special laws or international agreements to which the Philippines is a signatory effectively subjects the supply of such services to zero percent (0%) rate; xxxx It is undisputed that P.D. 1869, the charter creating P AGCOR, grants the latter an exemption from the payment of taxes. Section 13 of P.O. 1869 pertinently provides: Sec. 13. Exemptions. xxxx (2) Income and other taxes. - (a) Franchise Holder: No tax of any kind or form, income or otherwise, as well as fees, charges or levies of whatever nature, whether National or Local, shall be assessed and collected under this Franchise from the Corporation; nor shall any form of tax or charge attach in any way to the earnings of the Corporation, except a Franchise Tax of five (5%) percent of the gross revenue or earnings derived by the Corporation from its operation under this Franchise. Such tax shall be due and payable quarterly to the National Government and shall be in lieu of all kinds of taxes, levies, fees or assessments of any kind, nature or description, levied, established or collected by any municipal, provincial, or national government authority. (b) Others: The exemptions herein granted for earnings derived from the operations conducted under the franchise specifically from the payment of any tax, income or otherwise, as well as any form of charges, fees or levies, shall inure to the benefit of and extend to corporation(s), association(s), agency(ies), or individual(s) with whom the Corporation or operator has any contractual relationship in connection with the operations of the casino(s) authorized to be conducted under this Franchise and to those receiving compensation or other remuneration from the Corporation or operator as a result of essential facilities furnished and/or technical services rendered to the Corporation or operator. Petitioner contends that the above tax exemption refers only to PAGCOR's direct tax liability and not to indirect taxes, like the VAT. We disagree. A close scrutiny of the above provisos clearly gives PAGCOR a blanket exemption to taxes with no distinction on whether the taxes arc direct or indirect. We arc one with the CA ruling that PAGCOR is also exempt from indirect taxes, like VAT, as follows: Under the above provision [Section 13 (2) (b) of P.O. 1869], the term "Corporation" or operator refers to PAGCOR. Although the law does not specifically mention PAGCOR's exemption from indirect taxes, PAGCOR is undoubtedly exempt from such taxes because the law exempts from taxes persons or entities contracting with PAGCOR in casino operations. Although, differently worded, the provision clearly exempts PAGCOR from indirect taxes. In fact, it goes one step further by granting tax exempt status to persons dealing with PAGCOR in casino operations. The unmistakable conclusion is that PAGCOR is not liable for the ₱30, 152,892.02 VAT and neither is Acesitc as the latter is effectively subject to zero percent rate under Sec. 108 B (3 ), R.A. 8424. (Emphasis supplied.) Indeed, by extending the exemption to entitles or individuals dealing with PAGCOR, the legislature clearly granted exemption also from indirect taxes. It must be noted that the indirect tax of VAT, as in the instant case, can be shifted or passed to the buyer, transferee, or lessee of the goods, properties, or services subject to VAT. Thus, by extending the tax exemption to entities or individuals dealing with P AGCOR in casino operations, it is exempting P AGCOR from being liable to indirect taxes. The manner of charging VAT docs not make PAGCOR liable to said tax. It is true that VAT can either be incorporated in the value of the goods, properties, or services sold or leased, in which case it is computed as 1/11 of such value, or charged as an additional 10% to the value. Verily, the seller or lessor has the option to follow either way in charging its clients and customer. In the instant case, Acesite followed the latter method, that is, charging an additional 10% of the gross sales and rentals. Be that as it may, the use of either method, and in particular, the first method, does not denigrate the fact that PAGCOR is exempt from an indirect tax, like VAT. The rationale for the exemption from indirect taxes provided for in P.O. 1869 and the extension of such exemption to entities or individuals dealing with PAGCOR in casino operations are best elucidated from the 1987 case of Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. John Gotamco & Sons, Inc., where the absolute tax exemption of the World Health Organization (WHO) upon an international agreement was upheld. We held in said case that the exemption of contractee WHO should be implemented to mean that the entity or person exempt is the contractor itself who constructed the building owned by contractee WHO, and such does not violate the rule that tax exemptions are personal because the manifest intention of the agreement is to exempt the contractor so that no contractor's tax may be shifted to the contractee WHO. Thus, the proviso in P.D. 1869, extending the exemption to entities or individuals dealing with PAGCOR in casino operations, is clearly to proscribe any indirect tax, like VAT, that may be shifted to PAGCOR. Although the basis of the exemption of PAGCOR and Acesite from VAT in the case of The Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Acesite (Philippines)Hotel Corporation was Section 102 (b) of the 1977 Tax Code, as amended, which section was retained as Section 108 (B) (3) in R.A. No. 8424, it is still applicable to this case, since the provision relied upon has been retained in R.A. No. 9337. 40 Clearly, the assessments for deficiency VAT issued against PAGCOR should be cancelled for lack of legal basis. The Court also deems it warranted to cancel the assessments for deficiency withholding VAT pertaining to the payments made by PAGCOR to its catering service contractor. In two separate letters dated December 12, 2003 and December 15, 2003, the BIR conceded that the unmonetized meal allowances of PAGCOR's employees were not subject to fringe benefits tax (FBT). However, the BIR held PAGCOR liable for expanded withholding VAT for the payments made to its catering service contractor who provided the meals for its employees. Accordingly, the BIR assessed PAGCOR with deficiency withholding VAT for taxable year 1999 in the amount of ₱4,077 ,667.40, inclusive of interest and compromise penalty; and for taxable year 2000 in the amount of ₱l2,212, 199.85, exclusive of interest and penalties. 41 42 VAT exemption extends to Aeesite Thus, while it was proper for PAGCOR not to pay the 10% VAT charged by Acesite, the latter is not liable for the payment of it as it is exempt in this particular transaction by operation of law to pay the indirect tax. Such exemption falls within the fo1mer Section 102 (b) (3) of the 1977 Tax Code, as amended (now Sec. 108 [b] [3] of R.A. 8424), which provides: The payments made by PAGCOR to its catering service contractor are subject to zero-rated (0%) VAT in accordance with Section 13(2) of P.D. No. 1869 in relation to Section 3 of R.A. No. 7716, viz.: SEC. 13. Exemptions.(1) x x x Section 102. Value-added tax on sale of services.- (a) Rate and base of tax - There shall be levied, assessed and collected, a value-added tax equivalent to 10% of gross receipts derived by any person engaged in the sale of services x x x; Provided, that the following services performed in the Philippines by VAT registered persons shall be subject to 0%. xxxx (3) Services rendered to persons or entities whose exemption under special laws or international agreements to which the Philippines is a signatory effectively subjects the supply of such services to zero (0%) rate (emphasis supplied). (2) (a) x x x (b) Others: The exemption herein granted for earnings derived from the operations conducted under the franchise, specifically from the payment of any tax, income or otherwise, as well as any form of charges, fees, or levies, shall inure to the benefit and extend to corporation(s), association(s), agency(ies), or individual(s) with whom the Corporation or operator has any contractual relationship in connection with the operations of casino(s) authorized to be conducted under this Franchise and to those receiving compensation or other remuneration from the Corporation or operator as a result of essential facilities furnished and/or technical services rendered to the Corporation or operator. xxxx Under Section 33 of the NIRC, FBT is imposed as: SEC. 3. Section 102 of the National Internal Revenue Code, as amended, is hereby further amended to read as follows: A final tax of thirty-four percent (34%) effective January 1, 1998; thirty-three percent (33%) effective January 1, 1999; and thirty-two percent (32%) effective January 1, 2000 and thereafter, is hereby imposed on the grossedup monetary value of fringe benefit furnished or granted to the employee (except rank and file employees as defined herein) by the employer, whether an individual or a corporation (unless the fringe benefit is required by the nature of, or necessary to the trade, business or profession of the employer, or when the fringe benefit is for the convenience or advantage of the employer). The tax herein imposed is payable by the employer which tax shall be paid in the same manner as provided for under Section 57 (A) of this Code. "SEC.102. Value-added tax on sale of service and use or lease of properties. - x x x "(b) Transaction subject to zero-rate. - The following services performed in the Philippines by Vat-registered persons shall be subject to 0%: "x x xx FBT is treated as a final income tax on the employee that shall be withheld and paid by the employer on a calendar quarterly basis. As such, PAGCOR is a mere withholding agent inasmuch as the FBT is imposed on PAGCOR's employees who receive the fringe benefit. PAGCOR's liability as a withholding agent is not covered by the tax exemptions under its Charter. 45 "(3) Services rendered to persons or entities whose exemptions under special laws or international agreements to which the Philippines is a signatory effectively subjects the supply of such services to zero rate. The car plan extended by PAGCOR to its qualified officers is evidently considered a fringe benefit as defined under Section 33 of the NIRC. To avoid the imposition of the FBT on the benefit received by the employee, and, consequently, to avoid the withholding of the payment thereof by the employer, PAGCOR must sufficiently establish that the fringe benefit is required by the nature of, or is necessary to the trade, business or profession of the employer, or when the fringe benefit is for the convenience or advantage of the employer. 46 As such, the catering service contractor, who is presumably a VAT-registered person, shall impose a zero rate (0%) output tax on its sale or lease of goods, services or properties to PAGCOR. Consequently, no withholding tax is due on such transaction. 3. PAGCOR is liable for the payment of withholding taxes Through the letters dated December 12, 2003 and December 15, 2003, the BIRrecomputed the assessments for deficiency final withholding taxes on fringe benefits under Assessment No. 33-99 and Assessment No. 332000, respectively, as follows: 43 44 Period Covered Recomputed Amount Assessment No. 33-99 Final Withholding Tax on Fringe Benefits 1999 ₱13,337,414.58, inclusive of penalty and interest Assessment No. 33-2000 Final Withholding Tax on Fringe Benefits 2000 ₱12,212,199.85, exclusive of penalty and interest The amount of the assessment for deficiency expanded withholding tax under Assessment No. 33-99 remained at ₱3,790,916,809.16. We now resolve the validity of the foregoing assessments. 1âwphi1 a. Final Withholding Tax on Fringe Benefits The recomputed assessment for deficiency final withholding taxes related to the car plan granted to PAGCOR's employees and for its payment of membership dues and fees. PAGCOR asserted that the car plan was granted "not only because it was necessary to the nature of the trade of PAGCOR but it was also granted for its convenience." The records are lacking in proof as to whether such benefit granted to PAGCOR's officers were, in fact, necessary for PAGCOR's business or for its convenience and advantage. Accordingly, PAGCOR should have withheld the FBT from the officers who have availed themselves of the benefits of the car plan and remitted the same to the BIR. 47 As for the payment of the membership dues and fees, the Court finds that this is not considered a fringe benefit that is subject to FBT and which holds PAGCOR liable for final withholding tax. According to PAGCOR, the membership dues and fees are: 57. x x x expenses borne by [respondent] to cover various memberships in social, athletic clubs and similar organizations. x x x 58. Respondent's nature of business is casino operations and it derives business from its customers who play at the casinos. In furtherance of its business, PAGCOR usually attends its VIP customers, amenities such as playing rights to golf clubs. The membership of PAGCOR to these golf clubs and other organizations are intended to benefit respondent's customers and not its employees. Aside from this, the membership is under the name of PAGCOR, and as such, cannot be considered as fringe benefits because it is the customers and not the employees of PAGCOR who benefit from such memberships. 48 Considering that the payments of membership dues and fees are not borne by PAGCOR for its employees, they cannot be considered as fringe benefits which are subject to FBT under Section 33 of the NIRC. Hence, PAGCOR is not liable to withhold FBT from its employees. b. Expanded Withholding Tax 46. The breakdown of respondent's payments which were assessed expanded withholding tax by the BIR but which should not have been made subject thereto arc as follows: The BIR assessed PAGCOR with deficiency expanded withholding tax for the year 1999 under Assessment No. 33-99 amounting to ₱3,790,916,809.16, inclusive of surcharge and interest, which was computed as follows: 49 Taxable Basis per Investigation ₱ 2,441,948,878.00 Expanded Withholding Tax due per investigation Less: Tax paid 45,762,839.60 43,490,484.05 Deficiency Expanded Withholding Tax Due Add: 25% surcharge 20% interest per annum from ___ 12-20-02 Compromise Penalty TOTAL AMOUNT DUE & COLLECTIBLE ₱ 2,398,458,393. 95 1,392,433,415.21 ₱ 3, 790,891,809.16 ================== Later, BIR issued a letter dated December 12, 2003 showing therein a recomputation of the assessment, to wit: 50 ₱ 2,441,948,878.00 ================ 45,762,839.60 43,490,484.05 Taxable Basis per Investigation EWT due per investigation Less: Tax paid Def. EWT Add: Interest 1-26-00 to 12-26-03 Compromise Def. EWT ₱ 2,272,355.55 ₱l,780,311.85 25,000.00 1,805,311.85 ₱ 4,077,667.40 PAGCOR submits that the BIR erroneously assessed it for thedeficiency expanded withholding taxes, explaining thusly: 44. The computation made by the revenue officers for the year 1999 for expanded withholding taxes against respondent arc also not correct because it included payments amounting to ₱682,120,262 which should not be subjected to withholding tax; 45. Of the said amount, ₱194,999,366 cover importations or various items for the sole and exclusive use of the casinos x x x: xxxx a) Taxable Compensation Income amounting to ₱7l,6ll,563.60, representing salaries of contractuals and casuals, clerical and messengerial and other services, cost of COA services and unclaimed salaries and other benefits recognized as income but subsequently claimed (attached as Annexes "10" to "18" and made integral parts hereof); b) Prizes and other promo items amounting to ₱16,185,936.61 which were already subjected to 20% final withholding tax. Pursuant to Revenue Regulations 2-98, prizes and promo items shall be subject only to 20% final tax (attached as Annexes "19" to "51" and made integral parts hereof); c) Reimbursements amounting to ₱18,246,090.35 which were paid directly by agents/employees as over the counter purchases subsequently liquidated/reimbursed by PAGCOR pursuant to BIR rulings 129-92 and 34588; d) Taxes amounting to ₱6,679,807.53, the amount of which should not be subjected to expanded withholding tax for obvious reasons; e) Security Deposit amounting to ₱3,450,000.00 which was written off after the Regional Trial Court, Branch 226 of Quezon City through Presiding Judge, Leah S. Domingo-Regala, rendered a decision based on a compromise agreement in Civil Case No. 097-31299 entitled 'Felina Rodriguez-Luna, et al vs. Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation" (attached as Annex "52" and made an integral part hereof); 51 PAGCOR' s submission is partly meritorious. The Court finds that PAGCOR is not liable for deficiency expanded withholding tax on its payment for: (1) audit services rendered by the Commission on Audit (COA), amounting to ₱4,243,977.96, and (2) prizes and other promo items amounting to ₱16,185,936.61. 52 53 PAGCOR's payment to the COA for its audit services is exempted from withholding tax pursuant to Sec. 2.57.5 (A) of Revenue Regulation (RR) 2-98, which states: SEC. 2.57.5. Exemption from Withholding Tax –The withholding of creditable withholding tax prescribed in these Regulations shall not apply to income payments made to the following: (A) National government and its instrumentalities, including provincial, city or municipal governments; On the other hand, the prizes and other promo items amounting to ₱16,185,936.61 were already subjected to the 20% final withholding tax pursuant to Section 24(B)(l) of the NIRC. To impose another tax on these items would amount to obnoxious or prohibited double taxation because the taxpayer would be taxed twice by the same jurisdiction for the same purpose. 54 55 56 Hence, except for the foregoing, the Court upholds the validity of the assessment against PAGCOR for deficiency expanded withholding tax. We explain. consideration all the facts to which their attention was called. Hence, it is incumbent upon the taxpayer to credibly show that the assessment was erroneous in order to relieve himself from the liability it imposes. PAGCOR failed in this regard. Hence, except for the assessment for deficiency expanded withholding taxes pertaining to the payments made to the COA for its audit services and for the prizes and other promo items, the Court upholds the BIR's assessment for deficiency expanded withholding taxes. 59 Other than the ₱4,243,977.96 payments made to COA, the remainder of the ₱71,61 l,563.60 compensation income that PAGCOR paid for the services of its contractual, casual, clerical and messengerial employees are clearly subject to expanded withholding tax by virtue of Section 79 (A) of the NIRC which reads: Sec. 79 Income Tax Collected at Source.(A) Requirement of Withholding. - Every employer making payment of wages shall deduct and withhold upon such wages a tax determined in accordance with the rules and regulations to be prescribed by the Secretary of Finance, upon recommendation of the Commissioner: Provided, however, That no withholding of a tax shall be required where the total compensation income of an individual does not exceed the statutory minimum wage, or Five thousand pesos (₱5,000) per month, whichever is higher. WHEREFORE, the Court PARTIALLY GRANTS the petition for certiorari; ANNULS and SETS ASIDE the Resolutions dated December 22, 2006 and March 12, 2007 of the Secretary of Justice in OSJ Case No. 20041 FOR LACK OF JURISDICTION; DECLARES that Republic Act No. 7716 did not repeal Section 13(2) of Presidential Decree 1869, and, ACCORDINGLY, the PHILIPPINE AMUSEMENT AND GAMING CORPORATION is EXEMPT from value-added tax. The Court FURTHER RESOLVES to: In addition, Section 2.57.3(C) of RR 2-98 states that: (1) CANCEL Assessment No. 33-1996/1997 /1998 dated November 14, 2002, which assessed PHILIPPINE AMUSEMENT AND GAMING CORPORATION for deficiency value-added tax; SEC. 2.57.3 Persons Required to Deduct and Withhold. - The following persons are hereby constituted as withholding agents for purposes of the creditable tax required to be withheld on income payments enumerated in Section 2.57.2: (2) CANCEL Assessment No. 33-99 dated November 25, 2002, insofar as it assessed PHILIPPINE AMUSEMENT AND GAMING CORPORATION for deficiency - xxxx (a) value-added tax; (c) All government offices including government-owned or controlled corporations, as well as provincial, city and municipal governments. (b) expanded withholding value-added tax on payments made by PHILIPPINE AMUSEMENT AND GAMING CORPORATION to its catering service contractor; As for the rest of the assessment for deficiency expanded withholding tax arising from PAGCOR's (1) reimbursement for over-the-counter purchases by its agents amounting to ₱18,246,090.34; (2) tax payments of ₱6,679,807.53; (3) security deposit totalling ₱3,450,000.00; and (4) importations w01ih ₱194,999,366.00, the Court observes that PAGCOR did not present sufficient and convincing proof to establish its non-liability. (c) final withholding tax on fringe benefits relating to the membership fees and dues paid by PHILIPPINE AMUSEMENT AND GAMING CORPORATION for the benefit of its clients and customers; and With regard to the reimbursement for over-the-counter purchases by its agents, PAGCOR merely relied on BIR Ruling Nos. 129-92 and 345-88 to support its claim that it should not be liable to withhold taxes on these payments without submitting any proof to show that there were really actual payments made. There is also nothing in the records to show that the amount of ₱6,679,807.53 really represented PAGCOR's tax payments, or that the amount of ₱194,999,366.00 were, in fact, paid for PAGCOR's importations of various items in furtherance of its business. 57 58 Even the ₱3,450,000.00 security deposit that it claims to have been written-off based on the compromise agreement in Civil Case No. 097-31299 was not sufficiently proved to be tax exempt. The only document presented by PAGCOR to support its contention was a copy of the trial court's decision in the civil case. However, nowhere in the decision mentioned the security deposit. It is settled that all presumptions are in favor of the correctness of tax assessments. The good faith of the tax assessors and the validity of their actions are thus presumed. They will be presumed to have taken into 1âwphi1 (d) expanded withholding tax on compensation income paid by PHILIPPINE AMUSEMENT AND GAMING CORPORATION to the Commission on Audit for its audit services, and expanded withholding tax on the prizes and other promo items, which were already subjected to the 20% final withholding tax; (3) CANCEL Assessment No. 33-2000 dated March 18, 2003, insofar as it assessed PHILIPPINE AMUSEMENT AND GAMING CORPORATION for deficiency – (a) value-added tax; (b)expanded withholding value-added tax on payments made by PHILIPPINE AMUSEMENT AND GAMING CORPORATION to its catering service contractor; and (c) final withholding tax on fringe benefits relating to the membership fees and dues paid by PHILIPPINE AMUSEMENT AND GAMING CORPORATION for the benefit of its clients and customers; Respondent PHILIPPINE AMUSEMENT AND GAMING CORPORATION is DIRECTED TO PAY to the Bureau of Internal Revenue: (l) its deficiency final withholding tax on fringe benefits arising from the car plan it granted to its qualified officers and employees under Assessment No. 33-99 and Assessment No. 33-2000; and (2) its deficiency expanded withholding tax under Assessment No. 33-99, except on compensation income paid to the Commission on Audit for its audit services and on prizes and other promo items. Upon receipt of respondent PHILIPPINE AMUSEMENT AND GAMING COH.PORA TIO N's payment for the foregoing tax deficiencies, the Bureau of Internal Revenue is DIRECTED TO WITHHOLD 5% thereof and TO REMIT the same to the Office of the Solicitor General pursuant to Section 11(1) 60 of Republic Act No. 9417 (An Act to Strengthen the Office of the Solicitor General, by Expanding and Streamlining its Bureaucracy, Upgrading Employee Skills and Augmenting Benefits, and Appropriating Funds Therefor and for Other Purposes). No pronouncement on costs of suit. SO ORDERED.