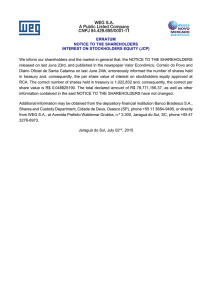

Jaganath A THEORY OF CORPORATE SCANDALS: WHY THE US AND EUROPE DIFFER The article is based basically on the differences of the structure of share ownership in US companies and European companies, and what effect does it have on the kind of fraud scandals that appear in each of them. The hypothesis of the author states that because of the characteristics of each of them and the corresponding information asymmetries of both systems, it can be either the Managers (US) or the Controlling Shareholders (Europe) who perpetrates fraud actions for their own benefits. This is also supported by the fact that US Companies have a dispersed ownership system while European Companies usually have a concentraded ownership system According to that assumption, corporate managers tend to engage in earning manipulations in US, while controlling shareholders tend to benefit from their position and exploit company’s assets. That would also explain why the Enron Case and the Parmalat Case are substantially different. FRAUD IN DISPERSED OWNERSHIP SYSTEMS During the 90’s the amount of financial statement restatements were tremendously increasing; from 1990 to 2002 the number had increased in 10 times. A financial statement restatement is the act of modifying previously presented financial data due to incorrect calculations and errors. Most of these errors were not simple technical adjustments; they involved deep changes on the financial results. As consequence, once the market realized about these restatements the value of the company’s shares would terribly decrease (to margins of 10% of the original value in 3 days or 25% in 4 months). The reason for this was that rather than honest mistakes, management had cheated on the statements. Basically they would allocate future expected earnings to previous periods, in order to generate the idea that the company’s profit was constant and therefore increase immediately the value of the shares. But managers didn’t perform these activities for the benefit of the company: they did for themselves. As the executive compensation changed during the 90’s from a cash-based system (pay specific and large amounts to executives) to a equity-based system (where executives receive most of their benefits in shares), the managers got a huge incentive to manipulate accountings; this was based on the increase of taxes on executives compensation and the shareholder’s intention to involve managers in the company’s performance. The problem with the equity-based system relies on the “price to earnings ratio”: as big is the value of the shares, as big are the manager’s earnings. So managers tried to inflate the price of the shares so that they could sell their equity at bigger prices; they were covered by the fact that they knew exactly when the bubble was going to burst so they could bail out before that happened. This scenario was allowed to happen because of gatekeeper’s failure to recognize the signals. That kind of problem didn’t occurred with the cash based system because managers had an incentive to don’t take risks and keep the company out of bankrupt, so they could receive their “salary” continuously. FRAUD IN CONCENTRATED OWNERSHIP REGIMES The previous scenario does not occur on companies with controlling investors, as these have the command and control of the board; if they try something tricky, they will be fired. It doesn’t have to do with shares prices as well because these companies will sell their entire block if they go public, nor to lack of regulation on public companies as controlling shareholders don’t care about inflating the shares value. It has to do with the extraction of private benefits of control. In these cases, the controlling shareholders use their power and influence on the management to perform activities for their own wealth, in detriment of the minority shareholders. The expropriation of private benefits usually occurs through financial transactions, where the ownership is diluted through public offerings and then the controlling shareholder uses a squeeze-out merger to force minority to sell their shares at a price under the real market value. Other method is the use of operational mechanisms, which is used in more developed countries. It usually takes the form transactions where the company affected transfer its assets to another company where the controlling shareholder of the first one, is actually the owner. In other words, the controlling shareholder steals from the company and the minority shareholders. As it happened in Parmalat, the controlling shareholder may simply pay other relevant shareholders for their support if it is necessary. This problems were allowed to happen due to the lack of rules protecting the small investors and, once again, to the bad performance of gatekeepers. GATEKEEPER FAILURE ACROSS OWNERSHIP REGIMES Both systems involve gatekeeper failures. The key difference is that on dispersed ownership the villains are the managers and the victim the shareholders, and in concentrated ownership the controlling shareholder overreach minority shareholders. The problem is that gatekeepers are hide by the companies so they have strong motives to not monitor correctly. This problem may be solved in dispersed ownership systems by redesigning the governance circuitry and creating an independent audit committee; in that way auditors and lawyers present don’t present their results to the people in charge to hire them (the managers); this has been applied through Sarvane-Oxley Act. Nevertheless, it is no applicable to concentrated ownership as controlling shareholders still have the power to influence on the independent audit committee. Potential new options for concentrated ownership are the imposition of supermajority votes and mandatory bid requirements. The participation of large banks has also helped in the monitoring activity. As a conclusion, the article states that different gatekeepers need to be designed into different governance systems to monitor for different abuses.