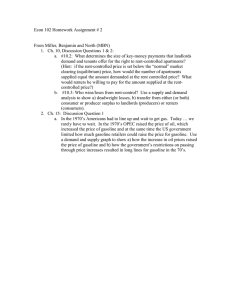

Dirlam and Kahn - Leadership and Cnflict in the Pricing of Gasoline

advertisement