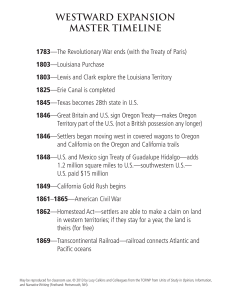

Deichmann 1 James Deichmann Professor Whited EXP 201-1 Close Reading: White Magic “You thought the West would free you from the version of yourself you’d gotten tangled up in. Instead, you become more bound to it than ever, tethered to the toilet bowl, wed to caustic drink” (Washuta 178). White Magic, by Elissa Washuta is a story written from multiple essays and memoirs, having a prevalent undertone of grief from abandonment, resulting in substance abuse and broken relationships. White Magic critiques white violence from settlers against indigenous communities and mentions the US government’s efforts to rewrite history through textbooks and monuments white settlers created and distributed on indigenous lands. Washuta refers to these efforts as magical artifacts and structures portions of her book on the common theme of magic. The author wrote this book to identify the elements of white settlement and how it made her vulnerable in school, in her romantic relationships, and her relationship with herself. To demonstrate Elissa Washuta’s perspective, this essay will focus on unique literary techniques Washuta employees to engage the reader. Elissa Washuta is not a traditional writer. She is not hesitant to use vulgar language when describing a situation of deep pain and frustration. She also uses language referencing colonization through settlement, magic, and whiteness to describe the world that has left her and her ancestors behind. As the book progresses, Washuta captures the unseen systemic forces that alter her life’s course. In the second act, she displays this journey through a game called Oregon Deichmann 2 Trail II that she played in her childhood and early adult years. The game experience in Oregon Trail II depends on how much bad luck you have while attempting to cross checkpoints along the Oregon Trail, it also includes the disasters you will encounter along the way. Elissa Washuta describes her experience of losing repetitively when bartering for information and talking ideas and suggestions from the other settlers. She then connects her loses in the game to her loses in real life, with the eventual result of getting tangled in the world of white settlement. The path through the video game resembles her journey to the West coast and Seattle in her broken early twenty years. Elissa narrates her first experience in the game when she comes across sudden danger from other settlers, connecting this occurrence with her boyfriend Philip. To Washuta, there is nothing very special about Philp, he is an upper-middle class white programmer with little to no enthusiasm in the relationship (Washuta 176). Washuta chooses Philip because he is harmless, and she feels she can navigate life (in relation to the Oregon Trail) easier with him. At other parts of the journey through the Oregon Trail, Elissa encounters traders, one of which was a Pawnee woman with a notable quote that summarizes the systemic source of Elissa’s frustration. “Why do you bother me? I don’t want to trade. The things that we get from the White travelers don’t make up for all that we lost (Washuta 180).” Washuta was told the best way to navigate the game was to wear Western boots outside and hope she isn’t greeted by bad luck (Washuta 199). The game, like her early twenties, is a nightmare, but some things have a small probability of getting better like when wounds from a gunshot unexpectedly heal in parallel to Washuta talking to a store clerk about life and struggle. Overall, the author’s use of metaphors in her writing in relation to Oregon Trail II provide a new way to convey the theme to the reader. Deichmann 3 Apart from Elissa’s damaging experiences in life paralleled to her unfortunate situations in Oregon Trail II, Washuta expands on her novel’s framework by including storytelling of white settlers erasing indigenous history and rewriting the historical roots of the Duwamish people. In the segment “White City,” Washuta recalls the depiction of Duwamish Chief Si’ahl’s defiant speech in 1854 expressing the exploitation and treachery by the white settlers (Washuta 156). Elissa explains that white settlers built an imaginary picture of the Indian people allowing the white men to continue to settle and cut the wood. From then on, more white authors continued to publish new renditions of Si’ahl’s speech to depict the white settlers as heroes. One of these poets was William Arrowsmith who shaped his own depiction of the address after labeling it impossible to do so (Washuta 159). “By telling stories over and over, we gave them life, by enacting narratives over and over, we gave them shape” Elissa writes. Overtime Washuta found herself tangled in the false narratives harnessed by white society, causing her to develop into a loop of emotional trauma and neglect. After analyzing other passages of White Magic, it is clear Elissa Washuta considered movies such as The Revenant, video games, and TV shoes because they had uncanny intersections to her life (Washuta 198). The method of including these snippets allowed the author to relate to other readers who have experienced severe trauma and were intertwined by systemic forces from white settlement. After struggling through addiction from laudanum and other substances, Elissa became sober with large fragments of her life destroyed by the abandonment of white settler culture, including individuals she had romantic connections to. Eventually, she was no longer tethered to the toilet bowl and shared her experiences through writing White Magic. Deichmann 4 Reference Page WASHUTA, ELISSA. White Magic. TIN HOUSE BOOKS, 2022.