S23 MGMT 6156 Module 8 Training and Development at RVA- A Nonprofit Organization

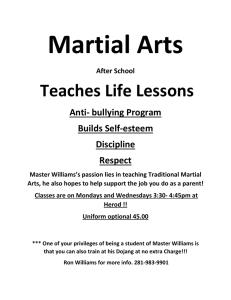

advertisement

S w TRAINING AND DEVELOPMENT AT RVA: A NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION Zunaira Saqib wrote this case solely to provide material for class discussion. The authors do not intend to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The authors may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentiality. Richard Ivey School of Business Foundation prohibits any form of reproduction, storage or transmission without its written permission. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Richard Ivey School of Business Foundation, The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada, N6A 3K7; phone (519) 661-3208; fax (519) 661-3882; e-mail cases@ivey.uwo.ca. Copyright © 2012, Richard Ivey School of Business Foundation Version: 2012-07-03 In mid-December 2009, Nick Williams, CEO of the Regional Voluntary Association (RVA), was not focused on Christmas gifts or New Year’s celebrations. He had just come back from a summit of nonprofit CEOs and was wondering what he could do with his limited resources to stop two of his employees from leaving. They would stay only if he promised them some development opportunities. This could mean professional development or further education, both rare not only in his organization but in the nonprofit sector as a whole. THE ORGANIZATION RVA was a regional voluntary sector network in the northwest of England. The organization, consisting of 150 members and a number of small offices across the region, worked for the betterment of local voluntary organizations by helping to provide community services, regenerate neighbourhoods, support individuals, promote volunteering and tackle discrimination. RVA had a membership of more than 6,500 volunteer and community groups. As CEO of the organization, Williams had seven people working under him at the head office in Manchester. NICK WILLIAMS Williams, a graduate of Liverpool Hope University, had worked in the private sector for six years before joining RVA in 2008. The experience of working in the private sector as compared to the non-profit sector was entirely different. In the private sector, personal development was part of his budget, although there was hardly any counseling available on how to use it. His job as CEO of the non-profit RVA should have been focused on networking and leading his organization to new heights. But, because of the chronic lack of funds, his job focus was on gaining funding not only to run his own organization but to help many other small groups who looked up to the RVA for fundraising and additional support. In these circumstances, spending money on the personal and career development of his own staff was almost out of the question. Williams spent a great amount of time generating funding for his own and his employees’ salaries. Sometimes, a couple of months would go by before he could pay his own salary. Authorized for use only in the course HCT Program at Fanshawe College taught by Various Instructors from 5/1/2023 to 9/1/2023. Use outside these parameters is a copyright violation. 9B12C032 9B12C032 According to the National Council for Voluntary Organizations (NCVO), there were 169,249 non-profit organizations in the United Kingdom. The sector had an income of £26,322.6 million (2003—04) and a workforce of 608,800 people, which equated to 2.2 per cent of the overall paid workforce1. The non-profit sector was not the first choice of many job seekers. Williams himself chose to work in the non-profit sector, but a majority of the people he knew worked there because they did not have a choice. With recession hitting Europe hard in the past three years, any job was a blessing. People came and went in the non-profit sector quickly. As soon as there was an opportunity to move to the public or the private sector, employees moved on. And Williams did not blame them. There were hardly any development opportunities in the non-profit sector. Most employees came to get experience, strengthen their resumes and then move on. Few people, he knew, came and stayed by choice. RECRUITMENTS AND RETENTION Recruitment and retention of employees was a major issue. Normally, RVA worked on projects that had a time scale of usually three to five years. It was expected that after funding ran out or the project was finished employees would leave. But, in reality, half would leave in the middle of the project. Knowing that their jobs were limited to the lifespan of the project, they would start looking for another job from day one and would leave as soon as another opportunity presented itself. Ironically, the other opportunities often weren’t very lucrative, but they did offer better job security than RVA. Williams would spend time to recruit people, train them and get to know them personally; then, when the project funding ran out, so did the people. This has been going on for some time now. One of the ongoing projects was halfway through its three-year tenure. Already, three good employees had left, and Williams had to recruit three more. Now, two of these new employees had given their notices as well. Hiring two replacements, training them and then seeing them leave before the project ended was another torment that awaited Williams in the new year. As CEO he did exit interviews of all employees who left. Sick of the situation, he decided to review the last 10 exit interviews in the past three years. There was something very common in all of them. Many employees wanted to stay but saw little career development opportunities. Most complained about the lack of training and development. The fact of uncertainty about job tenure was there, too. THE ISSUE Williams knew that some things were beyond his control. He had to let go of people after a certain amount of time as the projects they were hired to work on were completed. It was hard to shift people from one project to another since each project was unique. Funding was limited, and it was hard to fit more people in. There was little chance that he could develop career paths for employees. As CEO himself of the project-based non-profit organization, he could not show them a roadmap for them to become a manager or CEO in the next five to seven years. How could Williams retain employees for the whole life of a project? Scarce funding did not allow him to keep recruiting people. Constant recruitment involved cost and wasted training and time. He wanted to keep employees for the whole three or five years of the project timeline. The issue was how? Every year Williams was invited to the non-profit CEOs’ summit. This year he shared his concerns and was not surprised to find others in the same boat. They all suffered from high employee turnover and 1 Cabinet Office, Office of the Third Sector, UK, Key Facts on the Third Sector, July 2009, http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http://www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/media/231495/factoids.pdf, accessed June 1, 2012. Authorized for use only in the course HCT Program at Fanshawe College taught by Various Instructors from 5/1/2023 to 9/1/2023. Use outside these parameters is a copyright violation. Page 2 9B12C032 were struggling to keep employees for the whole project tenure. Some did try to implement some shortand long-term plans in their organizations. All had success and failure stories. After talking to many of them, Williams came to the conclusion that the only option for him was to offer employees training and development opportunities at the end of each project year. This could be a reason for many of them to stay, at least for the project tenure. Williams knew he could not give his employees a career path, but he could give them a roadmap of training and development, through which they could see a change in their profile, personality and resume after the completion of the project. This was hardly a fully fledged solution — it was only the tip of the iceberg. The real issue was the scarcity of funding. What sort of training and development could he offer? Classroom training, university and professional courses were all very expensive. How could he afford any of them? THE OPTIONS Keeping in view all the constraints, Williams came up with the idea of a team development program. In this program, teams combining senior and junior members were formed within the organization. The main task of the team would be to help each member learn something new. The junior members could share their knowledge of computers, IT, etc. while benefitting from senior members’ experience of being in the job for a long time. This program could be implemented at no extra cost. Williams considered four other options. 1. Deputation: At the CEO summit, it was suggested that employees be offered a short-term assignment to work in another organization. This would not only enhance the employees’ experience but they would also see the environment, culture and work of another organization. However, this option meant that funding had to be provided to pay for accommodation, food and travel to other cities. It would cost about £500 per employee for accommodation and food. 2. Small development courses: A nearby college offered personal development and skill development courses, normally lasting three to four days. However, this was expensive, as the fees were at least £200 per course. There were several options that could be considered; for instance, the participants and the organization could share the fee. There was a good chance that employees might agree to that, due to the financial crisis and bad job market. 3. Free training opportunities: Seminars and workshops on personal development and non-profit sector community building were available for free or at low cost. The issue was looking for the right ones for RVA’s employees. Although many general free seminars and workshops were on offer, it was hard to find employees who were interested in them. For specific hard skills or technical training, it was hard to find a specific employee who would like to develop such skills. 4. Government support: Recently, the government had introduced a support program for regional voluntary organizations that provided £2,000 per year for employee development. Spending that £2000 wisely and fairly was the challenge. Williams had two employees who were leaving, but he also had five other people still working in the organization. Employees’ details are given below in Exhibit 1. Williams needed to make a proper plan; he wondered if he should choose one option for all employees, or different options for different employees. Who would be happy with which option? Would implementing these options make employees stay for the whole project tenure? Should the government funding program (if it were available) be spent equally among all employees? Authorized for use only in the course HCT Program at Fanshawe College taught by Various Instructors from 5/1/2023 to 9/1/2023. Use outside these parameters is a copyright violation. Page 3 Page 4 9B12C032 Exhibit 1 Name Designation Emily (leaving) Tom (leaving) Michael Project 1 leader Finance coordinator Activities planner HR executive Project 2 leader Finance coordinator Activities planner Tania Stephen Gordon Gregson Tenure in years 1 Age Qualification Training attended 25 MA None 2 24 BA accounting 1 1.5 34 None 2.5 3 32 40 BA literature, in progress MA A levels 3.5 33 3 35 Diploma accounting A levels 3 None 1 None Authorized for use only in the course HCT Program at Fanshawe College taught by Various Instructors from 5/1/2023 to 9/1/2023. Use outside these parameters is a copyright violation. RVA EMPLOYEE DETAILS