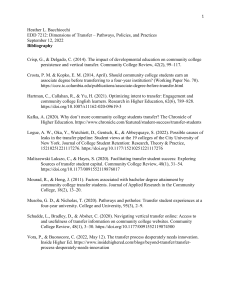

Knowledge Management Research & Practice ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tkmr20 Management strategies to mitigate knowledge hiding behaviours: symmetric and asymmetric analyses Dr Muhammad Waseem Bari, Mrs Irum Shahzadi & Dr Muhammad Fayyaz Sheikh To cite this article: Dr Muhammad Waseem Bari, Mrs Irum Shahzadi & Dr Muhammad Fayyaz Sheikh (2023): Management strategies to mitigate knowledge hiding behaviours: symmetric and asymmetric analyses, Knowledge Management Research & Practice, DOI: 10.1080/14778238.2023.2178344 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2023.2178344 Published online: 16 Feb 2023. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tkmr20 KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT RESEARCH & PRACTICE https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2023.2178344 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Management strategies to mitigate knowledge hiding behaviours: symmetric and asymmetric analyses Dr Muhammad Waseem Bari , Mrs Irum Shahzadi and Dr Muhammad Fayyaz Sheikh Lyallpur Business School, Government College University, Faisalabad, Pakistan ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The study investigates the impact of management strategies (reducing chain of command, developing informal interaction, implementing incentive policy, easy performance appraisal, encouraging higher interdependency, and open space workstations) to mitigate the knowl­ edge-hiding behaviours while using the psychological contract as a mediator between man­ agement strategies and knowledge-hiding behaviours. Symmetric (PLS-SEM) and asymmetric (fsQCA) methods are used to analyse time lag data collected from 457 employees of software houses. Except for the reducing chain of command, the PLS-SEM results show that all manage­ ment strategies and psychological contract have a significant role in reducing knowledgehiding behaviours. The fsQCA results suggest that all management strategies and psychologi­ cal contract play their role in different causal recipes while influencing the knowledge-hiding behaviours, however, developing informal interaction, implementing incentive policy, easy performance appraisal, and psychological contracts have more consistent contributions in these causal recipes. Received 15 April 2022 Revised 24 January 2023 Accepted 28 January 2023 1. Introduction Connelly et al. (2012) initially introduced the concept of knowledge hiding in the organisational context. Subsequently, many studies, to control this negative workplace behaviour, explore the antecedents and outcomes of knowledge hiding that include innova­ tion (Bogilović et al., 2017b), creativity (Černe et al., 2017), individual/organisational performance (Connelly et al., 2012), employee silence (Bari, et al., 2020), psychological contract breach (Bari, Ghaffar et al., 2020), team performance (Bogilović et al., 2017; Fong et al., 2018), cronyism, interpersonal rela­ tions (Connelly & Zweig, 2015), altruistic leadership (Abdillah et al., 2022), dark triad (Pan et al., 2018), and job security (Serenko & Bontis, 2016). Knowledge hiding is different from other negative behaviours in that knowledge hiders adopt straight denial or sometimes diplomatic behaviour to hide knowledge from the knowledge seekers (Bernatović et al., 2021). Therefore, Connelly et al. (2012) classify knowledge hiding into three distinctive categories namely, evasive hiding, playing dumb, and rationa­ lised hiding. Each knowledge-hiding behaviour (KHBs) has certain motives and outcomes. In evasive hiding, the knowledge holder intends to deceive others by giving false or partially incorrect information whereas, in playing dumb, the knowledge holder com­ pletely ignores or puts off others’ requests. On the other hand, in rationalised hiding, the knowledge CONTACT Dr Muhammad Waseem Bari School, Faisalabad, Pakistan © 2023 The Operational Research Society KEYWORDS Management strategies; knowledge hiding; psychological contract; fsQCA; PLS-SEM; software houses hider presents enough reasoning for not disclosing or sharing the requested information (Connelly et al., 2019, 2012). Considering this, researchers have emphasised that each category and its antecedents and outcomes should be examined explicitly. As a result, several studies have been conducted to exam­ ine the antecedents and outcomes of knowledge hid­ ing, particularly from a negative perspective, however, very few researchers have proposed empirical solu­ tions to control KHBs (Butt & Ahmad, 2020; Connelly et al., 2019). It is noted that the adoption of KHBs depends on the situation (Connelly & Zweig, 2015; Connelly et al., 2012), therefore, it is necessary to explore distinctive ways to control KHBs effectively. In this regard, Butt and Ahmad (2020) proposed six strategies to mitigate knowledge hiding (SMKH) in organisations. These strategies include reducing chain of command (RCC), developing informal interaction (DII), intro­ ducing and implementing incentive policy (IIP), initi­ ating easy performance appraisal (EPA), encouraging higher interdependency (EHI), and introducing open space work stations (OSWS; Butt & Ahmad, 2020). However, the literature lacks sufficient empirical evi­ dence to validate the effectiveness of these strategies. Butt and Ahmad (2020) have invited scholars to test the impact of proposed mitigating strategies on KHBs in different cultural contexts (Butt & Ahmad, 2020). In response to this call, this study aims at empirically testing and validating these strategies in the South muhammadwaseembari786@hotmail.com Government College University Faisalabad, Lyallpur Business 2 M. W. BARI ET AL. Asian context, which has been overlooked by previous researchers. Drawing on social exchange theory (SET; Blau, 1964), reciprocal trust between the knowledge holder and the knowledge seeker is inevitable for knowledge sharing and diminishing KHBs (Silva & Goncalves, 2016). Therefore, this study proposes that an intact psychological contract (PC) may enhance the effec­ tiveness of SMKH to decrease KHBs in organisations. Rousseau (1989) defines the PC as “an individual’s beliefs about the terms of the exchange agreement between employee and employer”. Rousseau (1989) categorised PC into three dimensions namely, transac­ tional PC, relational PC, and a balanced PC. The application of these three dimensions of PC may per­ form differently in different organisational cultures (Shaheen et al., 2019). The perceived mutual expecta­ tions between employees and the organisation develop a PC. The fulfilment/non-fulfilment of these mutual expectations can influence the performance and beha­ viours of both parties (Bari, et al., 2020; Chaudhry et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2018; Vui-Yee Koon, 2022). The PC is not limited to the relationship between employer and employee, it also exists between employ­ ees (Schalk & Roe, 2007). An intact PC is a vital factor in the organisation to reduce negative behaviours (Bari, et al., 2020). Thus, PC may act as a mediator between SMKH and KHBs that has not been empiri­ cally examined in previous studies. Hence, the objectives of this study are two-fold: first, to explore the impact of SMKH on KHBs (Playing dump, evasive hiding, and rationalised knowledge hiding) of employees of an organisation. Second, to examine how PC mediates the relation between SMKH and KHBs. To achieve the aforemen­ tioned objectives, this study has two research ques­ tions. First, what is the impact of SMKH on the three dimensions of KHBs? Second, how does PC mediate the relationship between SMKH and KHBs? For empirical investigation, data are collected from the employees of the software industry in Pakistan. The rationale behind the selection of the software industry is the workplace where knowledge workers are regu­ larly involved in creative and innovative activities, which heavily depend on knowledge. Secondly, pre­ vious studies have confirmed the existence of KHBs in the software industry of Pakistan (Bari, et al., 2020). Therefore, it is of great importance to examine the strategies to mitigate the KHBs in this industry. This study has at least three important contribu­ tions. First, this is the first study that empirically investigates the effectiveness of SMKH to control employees’ KHBs in software houses in a developing economy context i.e., Pakistan. Second, this study employs both symmetrical (Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling; Hair et al., 2016) and asymmetrical (Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2021) analyses to con­ firm the existence of KHBs in employees in the pre­ sence or absence of SMKH. Third, this study examines how PC is supportive of SMKH for diminishing the KHBs in software houses. 2. Literature review 2.1. Knowledge hiding Knowledge-hiding practices are found at different levels in different organisations and countries. For instance, 46% of Chinese and 76% of Americans are involved in knowledge-hiding practices in the work­ place (Pan et al., 2018; Peng, 2013; Z. Zhang & Min, 2021). The knowledge hiders have feelings of psycho­ logical ownership regarding the knowledge they owned, thereby, they show a high tendency to hide knowledge from others (Peng, 2013). Drawing on SET, KHBs are reciprocally developed between employees (Connelly et al., 2012). Knowledge hiders not only stop sharing their knowledge but also halt colleagues to develop innovative notions (Černe et al., 2014; Peng, 2013). Employees’ KHBs impede their creative skills and performance (Černe et al., 2014). Connelly and Zweig (2015) report that KHBs impair employees’ social relationships. Drawing on the conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll, 1989), Han et al. (2020) find that a competitive psychological climate is an important determinant of knowledge-hiding beha­ viour to stay competitive as compared to others. Knowledge hiding exists in three forms (Connelly et al., 2012) namely, playing dumb, evasive hiding, and rationalised hiding. Being an evasive knowledge hider an individual intends to deceive others by giving mis­ leading or incorrect information or making a bewildering promise to answer in the future. When an individual pretends to be unfamiliar with the requested knowledge and avoids providing the infor­ mation is referred to as playing dumb behaviour. An individual who presents enough reasoning for not disclosing or sharing requested information refers to as a rationalised knowledge hider (Butt & Ahmad, 2019; Connelly et al., 2012; Demirkasımoğlu, 2016; Webster et al., 2008). KHBs have several antecedents and negative consequences presented in the literature (Bari, Misbah et al., 2020; Butt & Ahmad, 2020; Demirkasımoğlu, 2016; Fong et al., 2018; Huo et al., 2016; Xiao & Cooke, 2018), which reflect this destruc­ tive workplace behaviour must be controlled through effective mitigating strategies. 2.2. Strategies to Mitigate Knowledge Hiding (SMKH) Organisations firmly believe in knowledge-sharing culture among employees, thus, organisations do KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT RESEARCH & PRACTICE make efforts to control the knowledge-hiding culture. Scholars have also highlighted the need for the identi­ fication of effective strategies. However, the effective­ ness of the management strategies and practices to control the knowledge-hiding culture within the orga­ nisations is debatable (Anand & Hassan, 2019; Butt & Ahmad, 2020; Connelly et al., 2019). Anand and Hassan (2019) classify the causes of knowledge hiding into four categories namely, indi­ vidual, organisational, job, and co-worker related. They suggest various remedies to curtail the conse­ quences of KHBs such as improving employee core self-evaluation, making employees aware of each other’s jobs, providing opportunities for socialising beyond work, 360-degree feedback on hiding acts, and facilitating a positive work and cross-linking environment. In addition, Abubakar et al (2019) also report that fair treatment by organisations makes their employees more involved in their work, and develops trust and sharing behaviours in the workplace. In a qualitative study, Butt and Ahmad (2020) propose six SMKH within the orga­ nisations to mitigate KHBs. These six strategies and their potential relationships with KHBs are dis­ cussed in the following lines. 2.3. Reducing chain of command Complex and bureaucratic structure-based organisa­ tions have more propensity for knowledge hiding. When a message transmits through a complex hier­ archy, there are higher chances of manipulation of the original content of the message (Butt & Ahmad, 2020). Easy access to top management develops mutual bonding that ultimately diminishes KHBs. Butt and Ahmad (2020) argue that while transmitting the mes­ sage through many layers, juniors may hide knowl­ edge from senior managers. Open doors for employees specifically, junior staff develop confidence and trust among employees and the organisation (Butt, 2021; Butt & Ahmad, 2020). The confidence and frequent direct interaction with seniors enhance the productiv­ ity and innovative skills of junior employees. A long and multi-reporting chain of command also creates problems such as miscommunication and delays in decision-making (Crumpton, 2013). A flatter or Semi flatter organisational structure not only reduces the cost of administrative/supervisory positions but also develops direct interaction and trust among workers, and promotes knowledge sharing culture (Schneckenberg, 2009; Webster et al., 2008) Hence, this study proposes that H1a: Reducing chain of command decreases KHBs. 3 2.4. Developing informal interaction Literature has underlined the detrimental effects of knowledge hiding on social relationships (Connelly & Zweig, 2015), employee creativity (Bogilović et al., 2017; Černe et al., 2014), and team creativity (Bogilović et al., 2017). Anand and Hassan (2019) suggest that providing opportunities for socialisation beyond work can engender positive work behaviours and overcome mutual work-related issues. Informal groups and communities make employees aware of each other’s jobs and also make them understand the obstructive effects of knowledge hiding in the work­ place. Informal interaction provides opportunities to share ideas and experiences that enhance cooperation, creativity, and confidence (Butt & Ahmad, 2020). The development of interpersonal trust may curtail unethi­ cal practices i.e., knowledge hiding among employees. Knowledge hiding impairs interpersonal relationships. Connelly et al. (2012) explain that personal conflicts can develop the intention of knowledge hiding while social interactions can curtail it. An open communica­ tion system (Shaheen et al., 2019), informal interaction (L. Zhang & Deng, 2014), social get-togethers, and informal friendship at the workplace (Enwereuzor et al., 2022) develop trust among workers and moti­ vate them to share their tacit as well as explicit knowl­ edge (Chen et al., 2014). Therefore, the study hypothesises that H1b: Developing informal interaction among employ­ ees reduces KHBs. 2.5. Introducing and implementing incentive policy A rational reward system encourages employees to share knowledge and discourages knowledge hiding simultaneously (Butt & Ahmad, 2020) which increases workers’ professional commitment to the firm (Butt, 2020). Suppiah and Sandhu (2011) document that rewards and recognition can motivate workers to share knowledge. De Almeida et al. (2016) endorse the relationship between incentives and benefits and knowledge-sharing behaviours. Offering incentives to managers for their knowledge-sharing behaviour at work promotes knowledge-sharing culture and dis­ courages KHBs (Connelly et al., 2019; Miminoshvili and Černe, 2021). Lee et al. (2014) also support the positive equation of performance-based compensation and knowledge-sharing behaviours. The monetary and non-monetary rewards enhance self-confidence in employees and motivate them intrinsically to share their explicit as well as tacit knowledge and skills 4 M. W. BARI ET AL. with colleagues (Anand & Hassan, 2019). Thus, this study proposes that H1c: Introducing and implementing incentive policy reduces KHBs. 2.6. Initiating easy performance appraisal Sometimes managers are hesitant to share their knowledge with colleagues due to fear and the strict performance criteria of the organisation (Butt & Ahmad, 2020; Černe et al., 2014). Organizations that emphasise on prevention of volunteer knowledge sharing may promote KHBs among managers. Conversely, organisations that loosely account for volunteer KHBs while evaluating employee perfor­ mance face fewer KHBs within an organisation (Butt, 2021; Butt & Ahmad, 2020). The strict questions regarding knowledge transfer during the process of performance appraisal may annoy the workers and induce them to hide their tacit knowledge (Connelly et al., 2019, 2012; Serenko & Bontis, 2016). When management enforces the incentive-based policy to share knowledge with subordinates (Butt & Ahmad, 2019), an ambiance of competition with co-workers starts. Bordia et al. (2006) confirm the negative rela­ tionship between employees’ fear of negative evalua­ tions and their knowledge-sharing intentions. An easy performance appraisal may work as a proxy for rewards as it looks unrealistic to offer tangible incen­ tives every time to the workers who adopt knowledgesharing behaviours (Fischer, 2022). Anand and Hassan (2019) suggest 360 degree feedback as an effective appraisal tool and strategy to create a positive culture of knowledge sharing in the organi­ sations. Thus, this study proposes that H1d: Initiating easy performance appraisal decreases KHBs. 2.7. Encouraging higher interdependency Butt and Ahmad (2020) reveal that interdependency at work discourages KHBs (Bari et al., 2019; Bari, et al., 2020). Interdependence reciprocates knowledgesharing culture and discourages KHBs (Z. Zhang & Min, 2021). Bogilović et al (2017) argues that knowl­ edge hiding from co-workers hinders not only employees’ creativity but also the team and organisa­ tions’ creative capabilities (Hernaus et al., 2017). Anand and Hassan (2019) favour teamwork and mutual collaboration of employees across departments to promote a knowledge-sharing culture. Previous research describes that task interdependence needs to be decided first before knowledge integration of the team (Fong et al., 2018; Kou, 2020). However, new researchers claim that mutual understanding of the team members for knowledge integration is more important than task interdependence decisions (Kou, 2020). Scholars believe that developing an attitude of interdependence among employees can motivate them to share knowledge and innovative ideas (Johnson, 2003; Kim et al., 2018). Thus, considering the above arguments, this study proposes that H1e: Encouraging higher interdependency among employees reduces KHBs 2.8. Open space workstation An open workstation engenders strong interpersonal relations among colleagues that reduce knowledgehiding. Anand and Hassan (2019) suggest that provid­ ing a conducive work environment for working cre­ ates a sense of connectivity among employees and restrains them from KHBs. Butt and Ahmad (2020) state that OSWS promotes knowledge sharing among employees and discourages KHBs because OSWS pro­ vides convenience in discussions and idea-sharing. Further, OSWS may help reduce competition among employees, improve collaboration, a friendly work environment, and effective communication among managers/ employees, and motivate employees to avoid knowledge-hiding practices. Peng (2013) explains that organisation-based psychological owner­ ship helps reduce self-perception of knowledge posses­ sion, as OSWS discourages a knowledge-hiding culture. Scholars recommend that organisations should provide an open workplace with resources and facilities, and remove barriers during communi­ cation among workers to enhance the collaboration and knowledge-sharing culture (Evans, 2012). The knowledge-sharing behaviour in the open workplace also depends on the nature of workplace interdepen­ dencies (Perumal & Sreekumaran Nair, 2022). When goals and resources are independent in the open work­ place, workers perceive non-competition and avoid knowledge hiding. On the other hand, when goals and resources are interdependent, colleagues perceive competition and adopt KHBs. Given the above discus­ sion, the study hypothesises that: H1f: Open space workstation reduces KHBs 2.9. Psychological contract (mediator) A PC is an informal and unwritten set of expectations between an employee and his employer that outlines an employment relationship. Rousseau (1989) defines the PC as an “individual’s beliefs about the terms of KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT RESEARCH & PRACTICE the exchange agreement between employee and employer”. The PC has three perspectives namely, transactional PC, relational PC, and balanced PC (Rousseau, 1989). In the organisational context, PC is considered an important individual mechanism that engenders the expected employment relationship and helps in setting the future behaviour of employees (Dai & Wang, 2016; Kingshott, 2006). An individual’s PC with the organisation depends on the individual’s expectations, which are implicit and perceptual (Rousseau, 1996), and likely to be revised over time (Guest, 2004). Mutual trust regulates reciprocal obli­ gations under PC (Dai & Wang, 2016) that further develops positive behaviour of employees (Dai & Wang, 2016; Neill & Adya, 2007). Dai and Wang (2016) report that a strong PC promotes a knowledgesharing culture (He & Li, 2011). Contrary, a PC breach develops counterproductive work behaviours in employees (Ng et al., 2014; Khalid et al., 2021). When an employee receives fair treatment and justi­ fied benefits from the organisation against his/her performance, he/she performs more positively (Bashir et al., 2021). Therefore, this study proposes that PC as a mediator enhances the impact of SMKH to decrease the KHBs. Hence, the following hypoth­ eses are formulated. H2a. PC mediates the relationship between RCC and KHBs. H2b. PC mediates the relationship between DII among employees and KHBs. Figure 1. Conceptual framework. 5 H2c. PC mediates the relationship between IIP and KHBs. H2d. PC mediates the relationship between EPA and KHBs. H2e. PC mediates the relationship between EHI among employees and KHBs. H2f. PC mediates the relationship between OSWS and KHBs. Figure 1 explains the positions of the variables and the direction of the hypotheses. 3. Methods 3.1. Population and data collection procedure The sample consists of randomly selected employees working in IT firms in Pakistan. IT sector is pre­ sumed to be a place of innovation and knowledge creation. It is also embedded with a dynamic busi­ ness environment therefore quite suitable for testing the hypotheses developed in this study. According to Pakistan Software Export Board (PSEB), currently, more than 4,641 (PSEB, 2020) IT-based registered companies are providing IT-related business solu­ tions and services. Considering the knowledge crea­ tion and sharing perspective, this study filters 337 firms that are providing business-related new soft­ ware development services in different cities of 6 M. W. BARI ET AL. Figure 2. Post-analysis model. Pakistan (PSEB 2021). Given the difficult circum­ stances due to COVID-19, an online questionnaire in English language is designed in “google forms”. A cover letter is attached with the questionnaire, which asks employees to take permission from their leadership before filling it out and be as rational as possible because this survey is based on their perception of a particular phenomenon not on right or wrong answers. The cover letter also describes what was attached to this survey form bearing the following instructions/information. First, it was asked the employees before filling out the survey form, got permission from your leader­ ship, and confirmed it on the provided place of the form. Second, the respondents were asked to provide answers as rationale as possible because this survey is just their perception about a particular phenom­ enon, not a right or wrong answer. Third, all data will be kept secret, no individual identification will be disclosed to anyone and these responses will be used only for research and analysis purposes. One thousand email addresses of the employees from the IT firms’ websites are collected. Three times lag approach is adopted while collecting the data. Each time lag has 45 days gap. In the first wave, 781 ran­ domly selected employees are approached and sent a web link of the survey form with questions about 6 SMKH. Out of 781, 642 employees filled the survey form (attrition rate 17.79%). In wave 2 after 45 days, 642 employees are asked questions about knowledge hiding. Out of 642 employees, 561 filled out the survey form (attrition rate 12.05%). In the third wave, again with 45 days gap, questions about PC and employees’ demographics are asked from 561 employees. Out of 561, 457 employees completed the survey form (attri­ tion rate 18.53%). The demographics of respondents are as follows. Gender: out of 457 employees, 332 are male and 125 are female. Education: out of 457 employees, 251 have master’s degrees, 112 have bachelor’s degrees, and 94 employees have higher secondary school degrees and some IT-related diplomas. Experience: 125 employees have more than 10 years of experience, 205 employees have 5–10 years of experience, and 127 employees have 0–5 years of experience. Position and Role: 61 employees are project managers and they have some strategic level roles, 127 are senior team leaders and have project development roles, 105 are supervisors and have operational roles, and 164 employees are at the input stage. 3.2. Measurement All items are measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). 3.2.1. Strategies to Mitigate Knowledge Hiding (SMKH) This study uses six SMKH developed by Butt and Ahmad (2020). The items used to measure these KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT RESEARCH & PRACTICE strategies are also adopted from Butt and Ahmad (2020). The following lines describe the items of SMKH. Reducing Chain of Command (5 items), sample item is “I can easily approach top management of my organization to discuss any innovative business idea”, Developing Informal Interactions (5 Items), sample item is “Informal social interactions improve my level of productivity and creativity”. Implementing Incentive Policy (3 items), sample item is “I am rewarded for my participation in knowledge sharing activities”. Easy Performance Appraisal (3 items), sample item is “My perfor­ mance is evaluated against my knowledge-sharing behavior”. Encourage Higher Interdependency (4 items), sample item is “I prefer to work in teams to get work-related information from team mem­ bers”. Open Space Work Stations (4 items), sample item is “Open space work station improves sociali­ zation at the workplace”. Cronbach’s Alpha values of these six SMKH are 0.873, 0.892, 0.731, 0.724, 0.758, and 0.879 respectively. 3.2.2. Knowledge hiding The authors adopt 12 items KHBs (Evasive hiding, playing dumb, and rationalised hiding) scale devel­ oped by Connelly et al. (2012). Respondents are asked to specify the extent to which they involve in any of mentioned behaviours. Sample items for eva­ sive hiding, playing dumb, and rationalised hiding are “agree to help him/her but never really intend to”, “I pretend that I do not know the information” (α = 0.00), “I explain that I would like to tell him/her but was not supposed to” respectively. Cronbach’s Alpha value is 0.919. 3.2.3. Psychological contract PC is measured with 11 items scale developed by Rousseau and Tijoriwala (1999). A sample item is “I do this job just for the money”. Cronbach’s Alpha value is 0.892. 3.3. Statistical tools, results, and findings Numerous traditional approaches such as Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLSSEM) and regression have been applied to examine the relationships of KHBs with their different ante­ cedents and consequences. However, the small R2 value in PLS-SEM and regression models can be misleading about the ability of different measures to sustainably explain the variance in the exogen­ ous constructs (Kaya et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2014). To account for such potential difficulties, we aug­ ment our PLS-SEM approach with a fuzzy set qua­ litative comparative analysis (fsQCA). While the PLS-SEM approach provides general tendencies of 7 the constructs towards the outcomes, fsQCA exposes the presence of different realities regarding the observed variables (Kaya et al., 2020). The fsQCA relies on configuration theory, which helps evaluate the holistic interactions among non-linear and disordered variables. The fsQCA approach facilitates the outcomes and predictor constructs to be on a fuzzy scale (continuous) not on a merely dichotomous scale (binary), as in other QCA-based approaches (Kaya et al., 2020; Kourouthanassis et al., 2017). Further, the PLSSEM approach provides symmetric analyses as it calculates average effects, whereas, the scope of the fsQCA approach can be extended to an asym­ metric analysis (Kaya et al., 2020; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2021). In sum, the fsQCA may extend our understanding of the research questions under investigation in an innovative way in addition to the PLS-SEM approach. The following sections describe symmetric and asymmetric approaches we adopt and their findings. 3.4. Symmetric analysis In this study, PLS-SEM is applied for symmetric modelling. The constructs’ reliability and validity are measured with different indicators such as item loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), rho_A, average variance extracted (AVE), con­ vergent validity, and discriminant validity. The retained factor loadings of all constructs are above 0.700 and significant (see, Table 1, and outer values of Figure 1; Hair et al., 2014). The convergent valid­ ity of this model is assessed with the estimations of Cronbach’s alpha, CR, rho_A, and AVE. Table 1 presents values of Cronbach’s alpha, CR, rho_A, and AVE that are above the recommended standards of 0.70, 0.70, .0.70, and 0.5, respectively (Hair et al., 2016). Fornell and Larcker’s criterion (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) and HTMT ratios (Hair et al., 2016) are used to confirm the discriminant validity. In Table 2, the square root of AVE for every variable is greater than its correlation coefficients with the other variables. In short, the results confirm the convergent validity and discriminant validity of the model. In Table 3, DII (β = −0.146, ρ = 0.045), IIP (β = −0.152, ρ = 0.028), EPA (β = −0.165, ρ = 0.034), and EHI (β = −0.184, ρ = 0.017) have a negative impact on KHBs while RCC (β = −0.027, ρ = 0.637) and OSWS (β = −0.29, ρ = 0.600) have no impact on KHBs. Therefore, H1b, H1c, H1d, H1e are accepted and H1a and H1f are rejected. Table 4, this study uses bootstrapping approach with a simulation of 5,000 samples with replacement, PC significantly mediates the impact of DII (β = −0.203, ρ = 2.878), IIP (β = −0.189, ρ = 2.174), EPA (β = −0.182, ρ = 2.162), 8 M. W. BARI ET AL. Table 1. Model measurement. Variables Reducing Chain of Command Developing Informal Interaction Implementing Incentive Policy Easy Performance Appraisal Encouraging Higher Interdependency Open Space Workstation KHBs Psychological Contract Items RCC-1 RCC-2 RCC-3 RCC-4 DII-1 DII-2 DII-3 DII-4 DII-5 IIP-1 IIP-2 IIP-3 EPA-1 EPA-2 EPA-3 EHI-1 EHI-2 EHI-3 EHI-4 OSWS-1 OSWS-2 OSWS-3 OSWS-4 KHBs-1 KHBs-2 KHBs-3 KHBs-4 KHBs-5 KHBs-6 KHBs-7 KHBs-8 KHBs-9 KHBs-10 KHBs-11 KHBs-12 PC-1 PC-2 PC-3 PC-4 PC-5 PC-6 PC-7 PC-8 PC-9 PC-10 PC-11 Factor Loadings 0.811 0.861 0.883 0.847 0.825 0.859 0.850 0.804 0.837 0.801 0.759 0.858 0.815 0.786 0.800 0.718 0.817 0.679 0.796 0.876 0.802 0.883 0.862 0.800 0.793 0.735 0.783 0.765 0.731 0.751 0.806 0.716 0.732 0.784 0.697 0.829 0.834 0.802 0.796 0.821 0.814 0.806 0.797 0.824 0.799 0.820 Cronbach’s Alpha 0.873 rho_A 0.875 CR 0.913 AVE 0.634 0.892 0.894 0.920 0.697 0.731 0.737 0.848 0.651 0.724 0.738 0.842 0.640 0.758 0.779 0.840 0.569 0.879 0.888 0.917 0.634 0.919 0.905 0.928 0.560 0.892 0.889 0.855 0.661 Note: CR = Composite Reliability, AVE = Average Variance Extracted Table 2. Discriminant validity. Fornell-Larcker Criterion Constructs DII EHI EPA IIP KHBs OSWS PC RCC Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) DII EHI EPA IIP KHBs OSWS PC RCC 0.835 0.091 0.755 0.174 0.370 0.800 0.525 0.212 0.414 0.807 −0.169 −0.111 −0.192 −0.187 0.748 0.251 0.237 0.501 0.332 −0.156 0.857 0.513 0.267 0.514 0.570 −0.183 0.465 0.813 0.247 0.233 0.474 0.255 −0.147 0.649 0.427 0.851 DII EHI EPA 0.118 0.204 0.646 0.176 0.275 0.555 0.284 0.455 0.279 0.137 0.259 0.295 0.249 0.536 0.206 0.623 0.606 0.586 IIP KHBs OSWS PC 0.219 0.398 0.161 0.678 0.180 0.316 0.161 0.504 0.730 0.467 RCC Note: RCC = Reducing Chain of Command, DII = Developing Informal Interaction, IIP = Implementing Incentive Policy, EPA = Easy Performance Appraisal, EHI = Encouraging Higher Interdependency, OSWS = Open Space Work Station, KHBs = KHBss, PC = Psychological Contract EHI (β = −0.218, ρ = 3.141), and OSWS (β = −0.141, ρ = 1.969) on KHBs. However, PC fails to mediate thesignificant effect of RCC on KHBs (β = −0.056, ρ = 0.669). Thus, H2b, H2c, H2d, H2e, and H2f are accepted based on empirical support, and H2a is rejected due to lack of evidence. Figure 2 explains the post analyses results. 3.5. Asymmetric analysis The fsQCA is an asymmetric approach, which is based on fuzzy logic and fuzzy sets. It has multiple signifi­ cances. First, beta and correlation coefficients in the regression analysis are not sufficient to explain the relationship between two or more constructs. However, fuzzy sets are very effective in this scenario KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT RESEARCH & PRACTICE 9 Table 3. Direct relationship. Structural Paths RCC→KHBs DII→ KHBs IIP→ KHBs EPA→ KHBs EHI → KHBs OSWS → KHBs Path co-efficient (t-value) −0.027, (0.472) −0.146, (2.694) −0.165, (3.062) −0.152, (2.865) −0.184, (3.711) −0.029, (0.525) Confidence interval (95%) (−0.133–0.090) (−0.289 − 0.014) (−0.387 − 0.064) (−0.314 − 0.038) (−0.431–0.109) (−0.133 0.078) f2 Effect size 0.001 0.026 0.023 0.032 0.038 0.001 p-Value 0.637 0.045 0.028 0.034 0.017 0.600 Results H1a, Rejected H1b, Accepted H1c, Accepted H1d, Accepted H1e, Accepted H1f, Rejected Note: Note: RCC = Reducing Chain of Command, DII = Developing Informal Interaction, IIP = Implementing Incentive Policy, EPA = Easy Performance Appraisal, EHI = Encouraging Higher Interdependency, OSWS = Open Space Work Station, KHBs = KHBs, PC = Psychological Contract Table 4. Mediation effect. Paths RCC→PC→KHBs DII→ PC→KHBs IIP→ PC→KHBs EPA→ PC→KHBs EHI → PC→KHBs OSWS → PC→KHBs Indirect Effects −0.056 −0.203 −0.189 −0.182 −0.218 −0.141 T Statistics 0.669 2.878 2.174 2.162 3.141 1.969 Confidence Interval (95%) −0.213 0.110 −0.339 − 0.047 −0.304 − 0.036 −0.281 − 0.029 −0.411 − 0.059 −0.260 − 0.025 p-Value 0.502 0.020 0.021 0.024 0.013 0.048 Results H2a, Rejected H2b, Accepted H2c, Accepted H2d, Accepted H2e, Accepted H2f, Accepted Note: Note: RCC = Reducing Chain of Command, DII = Developing Informal Interaction, IIP = Implementing Incentive Policy, EPA = Easy Performance Appraisal, EHI = Encouraging Higher Interdependency, OSWS = Open Space Work Stations, KHBs = KHBs, PC = Psychological Contract (Kaya et al., 2020; Olya & Altinay, 2016; Wu et al., 2014) because fsQCA provides manifold solutions that can provide the same output. Second, the effectiveness of symmetric methods (i.e., multiple regression analy­ sis, MRA, and structural equation modelling, SEM) while testing a model with several endogenous con­ structs that are highly correlated is questionable due to collinearity (Olya & Altinay, 2016; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2021). Therefore, while applying MRA and SEM models, the big size of a sample is not helpful to control the impact of confounding factors such as education, experience, gender, age, etc. (Woodside, 2013). Third, practically, an outcome of a construct depends on the joint impact of multiple antecedents which is known as an algorithm in an asymmetric approach (Kaya et al., 2020; Woodside, 2013). In symmetric methods, high values of an endogenous construct (say A) are enough for forecasting the occurrence of high values of an endogenous con­ struct (say B), however, a high score of (A) does not confirm the occurrence of a high score of (B). On the other hand, in asymmetric association, high scores of an endogenous construct (A) are impor­ tant and enough for predicting the existence of a high score construct (B; Kaya et al., 2020). Fourth, the asymmetric method is conditional on both logic (i.e., negative and positive; Woodside, 2013), because dependence on one logic can be inappropriate. 3.5.1. Calibration The fsQCA is based on the logic of set membership, therefore, data should be converted into fuzzy sets scaling from one (full membership) to zero (full nonmembership; Afonso et al., 2018; Ragin, 2009). This study uses standardised latent variables calculated through PLS-SEM (SmartPLS.3) for all constructs cases (conditions & outcomes; Hair et al., 2016; Ragin, 2009). The calibration procedure needs to define 3 anchors: full non-membership, crossover point, and full membership (Afonso et al., 2018; Ragin, 2009; Silva & Goncalves, 2016). Therefore, in this paper the rating of 3 is full membership, zero is the crossover point, and −3 is full non-membership. 3.5.2. Necessary conditions Necessary conditions play an important role in fsQCA to complete the analysis of sufficient conditions (Afonso et al., 2018; Schneider & Wagemann, 2010). This paper investigates the two endogenous con­ structs, psychological contract, and knowledge hiding in the PLS-SEM model as outcome conditions. While conducting the fsQCA, six antecedent conditions for the outcome PC (RCC, DII, IIP, EPA, EHI, and OSWS) and seven antecedent conditions for the out­ come KHBs (RCC, DII, IIP, EPA, EHI, OSWS, and PC) are considered. To determine whether any of the six or seven conditions are necessary for PC or KHBs respectively, this study measures whether the condi­ tion is consistently present or absent in all cases where the outcome is present or absent (Kaya et al., 2020; Rihoux & Ragin, 2008). Hence, PC or KHBs is attain­ able if the condition in question happens. The level to which the cases follow this rule depicts “consistency”. As per scholars’ recommendation, a relevant consis­ tency value above the threshold of 0.8 or 0.9 indicates a condition is “almost always necessary” or “neces­ sary” respectively (Afonso et al., 2018; Ragin, 2009). Table 5 shows the fsQCA test results on the necessity of the conditions concerning both the outcomes PC 10 M. W. BARI ET AL. Table 5. Analysis of necessary conditions. S. No. Conditions Consistency Outcome = PC, Consistency Cut = 0.9, Coverage Cut = 0.80 1 DII+IIP 0.945 2 DII+EPA 0.959 3 DII+OSWS 0.940 4 EPA+OSWS 0.951 Outcome = ~PC, Consistency Cut = 0.9, Coverage Cut = 0.80 1 ~DII+~IIP 0.942 2 ~DII+~OSWS 0.965 3 ~IIP+~EPA 0.955 4 ~IIP+~OSWS 0.962 Relevance of Necessity Coverage 0.824 0.793 0.804 0.809 0.823 0.803 0.806 0.813 0.820 0.819 0.818 0.808 0.844 0.849 0.846 0.841 0.792 0.783 0.810 0.802 Outcome = KHBs, Consistency Cut = 0.9, Coverage Cut = 0.80 1 ~DII+~PC 0.910 2 ~IIP+~PC 0.905 Outcome = ~KHBs, Consistency Cut = 0.9, Coverage Cut = 0.80 No combination of conditions meets the criteria of the necessary condition Note: RCC = Reducing Chain of Command, DII = Developing Informal Interaction, IIP = Implementing Incentive Policy, EPA = Easy Performance Appraisal, EHI = Encouraging Higher Interdependency, OSWS = Open Space Work Station, Knowledge Hiding Behaviours= KHBs, PC = Psychological Contract and KHBs. The results present that no necessary con­ ditions are identified for PC and KHBs 3.5.3. Sufficient conditions The truth table provides the base for the analyses of sufficient conditions (Ragin, 2009). The fsQCA algo­ rithm is used to develop the truth tables for both out­ comes, PC, and KHBs. This study uses a frequency threshold of 10 observations to eliminate comparatively less significant configurations (Rihoux & Ragin, 2008). It helps reduce truth tables for finding meaningful con­ figurations. Scholars suggest that post-frequency restriction, a minimum of 80% of the cases should stay in the sample set (Ragin, 2009). The frequency threshold confirms that 83% and 88% of the cases are part of the analyses for KHBs and PC respectively. To confirm which configurations are sufficient for attain­ ing the outcomes, this study uses 0.80 (Ragin, 2009; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2021) as the threshold for consis­ tency and 0.5 threshold for the proportional reduction in inconsistency (PRI) to control the occurrence of simultaneous subset associations of attribute Table 6. Analysis of sufficiency. S. No. Conditions Consistency Outcome = PC, Consistency Cut = 0.9, PRI. Cut = 0.5, n. Cut = 10 1 RCC*IIP*EPA*EHI 0.976 2 RCC*IIP*EPA*OSWS 0.973 3 RCC*~DII*~IIP*EPA*~EHI 0.967 4 ~DII*~IIP*EPA*EHI*~OSWS 0.963 5 ~RCC*~DII*IIP*EPA*~EHI*~OSWS 0.975 6 RCC*~DII*~IIP*~EPA*EHI*OSWS 0.974 Solution 0.925 0.844 0.669 Outcome = ~PC, Consistency Cut = 0.9, PRI. Cut = 0.5, n. Cut = 10 1 ~RCC*~EPA*~EHI*~OSWS 0.965 2 ~DII*~IIP*~EPA*~OSWS 0.974 3 ~IIP*~EPA*~EHI*~OSWS 0.971 4 ~RCC*~DII*~IIP*~EHI*~OSWS 0.979 Solution 0.955 Coverage Unique Coverage Proportional Reduction Inefficiency (PRI) 0.673 0.694 0.547 0.575 0.533 0.544 0.014 0.021 0.012 0.021 0.013 0.027 0.872 0.863 0.571 0.474 0.510 0.592 0.665 0.879 0.662 0.630 0.789 0.041 0.701 0.008 0.023 0.826 0.879 0.856 0.883 0.826 Outcome = KHBs, Consistency Cut = 0.9, PRI. Cut = 0.5, n. Cut = 10 1 ~RCC*~DII*~IIP*~EPA*~OSWS*~PC 0.900 2 ~RCC*~DII*~IIP*~EHI*~OSWS*~PC 0.901 3 ~RCC*~DII*~EPA*~EHI*~OSWS*~PC 0.904 4 ~RCC*~IIP*~EPA*~EHI*~OSWS*~PC 0.908 5 ~DII*~IIP*~EPA*~EHI*~OSWS*~PC 0.906 Solution 0.895 0.599 0.575 0.576 0.574 0.586 0.678 0.041 0.017 0.018 0.016 0.028 0.652 0.640 0.653 0.653 0.662 0.675 Outcome = ~KHBs, Consistency Cut = 0.9, PRI. Cut = 0.5, n. Cut = 10 1 RCC*~DII*~IIP*~EPA*EHI*~PC 0.943 2 RCC*~DII*~IIP*EPA*~OSWS*~PC 0.953 3 RCC*~DII*IIP*EPA*OSWS*~PC 0.957 4 RCC*DII*IIP*EPA*EHI*PC 0.964 5 RCC*DII*IIP*EPA*OSWS*PC 0.954 6 ~DII*~IIP*EPA*EHI*~OSWS*~PC 0.929 7 ~RCC*~DII*IIP*EPA*~EHI*~OSWS*~PC 0.941 8 ~RCC*DII*IIP*~EPA*~EHI*~OSWS*~PC 0.942 9 RCC*DII*~IIP*~EPA*~EHI*~OSWS*~PC 0.942 Solution 0.859 0.522 0.506 0.531 0.620 0.633 0.528 0.494 0.522 0.492 0.793 0.014 0.001 0.007 0.005 0.010 0.008 0.003 0.014 0.006 0.600 0.643 0.675 0.757 0.718 0.538 0.564 0.575 0.506 0.496 Note: RCC = Reducing Chain of Command, DII = Developing Informal Interaction, IIP = Implementing Incentive Policy, EPA = Easy Performance Appraisal, EHI = Encouraging Higher Interdependency, OSWS = Open Space Work Station, Knowledge Hiding Behaviours= KHBs, PC = Psychological Contract KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT RESEARCH & PRACTICE combinations in both the outcomes and their negations as well (Afonso et al., 2018; Schneider & Wagemann, 2012, p. 242). The fsQCA software offers three types of solutions (i.e., parsimonious, complex, and intermedi­ ate; Ragin, 2009). Table 6 reports the complex solutions for both outcomes (PC and KHBs). The coverage and consistency values for each solution and their specific configurations are above the thresholds. 3.5.4. Causal recipes for the presence of the outcomes The complex solution for the presence of a PC has six configurations (Table 6). For instance, configuration 1 depicts that effectively reducing the chain of com­ mand, effective implementation of incentive policy, easy performance appraisal, and higher interdepen­ dency among employees (RCC*IIP*EPA*EHI) pro­ motes psychological contract. Similarly, the complex solution for the presence of KHBs has five configura­ tions (Table 6). The results depict these five config­ urations are negation-based combinations of different causal conditions. For instance, the first configuration explains that combining negation of reducing the chain of command, developing informal interaction, implementation of incentive policy, easy performance appraisal, open space workstation, and PC (~RCC*~DII*~IIP*~EPA*~OSWS*~PC) promotes KHBs at the workplace. 3.5.5. Causal recipes for the negation of the outcomes The fsQCA provides additional analyses about the inverse of the outcome to explain which configuration can consistently lead to the negation of the outcome (Schneider & Wagemann, 2012). As compared to PLSSEM, the fsQCA may provide different results from the configurations leading to the outcome (presence) to the configurations leading to the negation of the outcome (absence; Afonso et al., 2018; Rihoux & Ragin, 2008). The present study also investigates which conditions consistently lead to ~PC and ~KHBs. Table 6, the results of ~PC depict the four configurations that have met the threshold of consis­ tency as all values are greater than 0.9. These results show four configurations are consistently associated with ~psychological contract. Similarly, this study examines which conditions consistently lead to ~KHBs at the frequency threshold 10, consistency 0.9, and PRI 0.5. Table 6, The fsQCA generates nine configurations with different combinations to negate the KHBs. For instance, in the first configuration, presence of reduced chain of command and higher interdependency among employees, and in absence of informal interactions, Incentive Policy, Easy Performance Appraisal, and PC decrease knowledge hiding (RCC* ~DII*~IIP* ~EPA *EHI *~PC). 11 4. Discussion The objective of this study is to evaluate the impact of different management strategies to mitigate knowl­ edge hiding in the workplace, and the absence of these strategies, how KHBs develop. Besides, how psy­ chological contact mediates the impact of these man­ agement strategies on KHBs. This study uses both symmetric (PLS-SEM) and asymmetric (fsQCA) approaches to investigate the phenomenon. The results of this study are based on the data provided by 684 employees working in IT firms in Pakistan. The final results from the PLS-SEM show that four ante­ cedents (DII, IIP, EPA, and EHI) have a significant negative impact on KHBs, however, two antecedents (RCC and OSWS) have no significant impact on KHBs. PC mediates the negative impact of five ante­ cedents (DII, IIP, EPA, EHI, OSWS) on KHBs. On the other hand, fsQCA results present a detailed under­ standing of how these six antecedent conditions sup­ port psychological contract. For instance, EPA consistently play role in all six configurations to develop PC (also in line with PLS-SEM results). Similarly, RCC also consistently appears in four out of six configurations and supports PC. In contrast, Table 6 shows four antecedent conditions in combina­ tion impact PC negatively. For example, ~OSWS con­ sistently appears in all four conditions and confirms that the absence of OSWS is a problem in the devel­ opment of the PC. Table 6, considering the KHBs as an outcome, fsQCA provides five recipes based on different ante­ cedent combinations. From these five combinations of antecedents, ~PC and ~OSWS consistently appears in all five recipes and confirm that the absence of PC and OSWS promotes KHBs. Similarly, Table 6 presents nine recipes based on different combinations of ante­ cedents that negate KHBs. In these nine recipes, the antecedents, DII, IIP, EPA, EHI, and PC are consis­ tently absent/present to negate KHBs. The results of the net effect present a R2 value of 52% for a PC while the outcome of the combinatory effects presents an overall solution coverage of 84% for PC presence and 78% for ~PC outcome condition. Similarly, the R2 value for KHBs is 46% while the analysis of the com­ bined recipe effects shows an overall solution coverage of 67% for KHBs’ existence and 79% for the negation of KHBs. The results of this study are in line with previous studies and indicate that the management strategies (RCC, DII, IIP, EPA, HI, and OSWS) can play an effective and significant role to decrease the KHBs (Butt, 2020, 2020; Butt & Ahmad, 2019). PC acts as a bridge to develop trust among workers and promote knowledge-sharing culture (Bari, Misbah et al., 2020; Connelly & Kevin Kelloway, 2003; Khoreva & Wechtler, 2020). Although, all recommended 12 M. W. BARI ET AL. management strategies (RCC, DII, IIP, EPA, EHI, and OSWS) and PC with different combined recipes (Table 6) play their role to change the KHBs of the workers, however, DII, IIP, EPA, EHI, and PC con­ sistently play their role (presence/absence) in different combinations to decrease knowledge hiding practices. This study has conducted analyses on the responses collected from the employees working in software houses in Pakistan. Different software houses have different organisational structures, places, and sizes. Therefore, the occurrence of the phenomenon (knowl­ edge hiding) and application of the SMKH may be different in different organisations. For instance, the workplace of some software houses may be small and they already have installed OSWS. Similarly, flat or semi-flat organisational structures do not need to focus on RCC. On the other hand, for the software houses that already have applied the job interdepen­ dence approach, the chances of knowledge hiding may be less as compared to other ones. 4.1. Theoretical contribution The theoretical framework of this study is based on SET (Blau, 1964) and it is hypothesised that certain management strategies (RCC, DII, IIP, EPA, EHI, OSWS; Butt & Ahmad, 2020)can help to control KHBs of workers at the workplace. In addition, PC can strengthen these management strategies to control KHBs. To confirm the application of SET, this study employs two methods PLS-SEM and fsQCA. The results of both methods (PLS-SEM & fsQCA) con­ firms the effectiveness and significance of all proposed SMKH (except RCC which is not significant through PLS-SEM) to decrease the KHBs. Moreover, the said methods also confirm the significant role of PC to increase the efficacy of SMKH and decreasing the KHBs. These results support Blau’ theory of social exchange (Blau, 1964). The fsQCA approach further elaborates the results by highlighting which individual strategy and combinations of SMKH (Table 6) consis­ tently support SET and required to control the KHBs. PLS-SEM based results indicate that OSWS strategy has no direct significant effect on KHBs, however, as a mediator, PC enhances its significance to control the KHBs, and supports the application of SET. should promote social interaction-based activities i.e., social get gathers, and open-place communication dis­ cussions. Second, managers should arrange knowl­ edge-based activities and provide awareness about the outcomes of knowledge sharing and KHBs. Third, although all proposed SMKH are effective to control KHBs, however, PC is imperative. Without mutual trust, it is very difficult for managers to moti­ vate employees to knowledge sharing. For instance, OSWS has no direct significant effect on KHBs but PC significantly mediates this relationship. Therefore, managers should promote a trusting culture in the workplace. Fourth, to build trust among employees, job interdependence is an effective strategy (Fong et al., 2018). Fifth, an appraisal strategy based on reward against knowledge sharing can help control KHBs. 4.3. Limitations and directions for future studies This study has certain limitations and future research directions. First, the objective of this study is to investigate the effectiveness of SMKH proposed by (Butt, 2020; Butt & Ahmad, 2020) in their exploratory studies. Although the empirical investigation in this study has proved the signifi­ cance of the SMKH, in the future, further manage­ ment strategies and practices should be explored for the effective controlling of KHBs. Second, the appli­ cation of these SMKH is checked in one industry (IT), and the responses of other industries may be different. Therefore, in the future, industry-based comparative studies are recommended. Third, dif­ ferent cultures and soft issues of human resources can impact the significance of the SMKH differently. Thus, in the future, cross-culture/border studies are recommended. Fourth, the time lag method is used for data collection which may limit the generalisa­ bility of this study. Therefore, a longitudinal study can be conducted for the long-term application of these strategies (Butt, 2020). Fifth, this study uses PC as a mediator, in the future, other variables (workplace democracy, organisational justice) as a mediator and moderators (job interdependence) can be checked. Disclosure statement 4.2. Managerial implications The outcomes have significant managerial workplace implications because they enhance the stakeholders’ understanding of which management strategies/mea­ sures can motivate employees to avoid KHBs and adopt knowledge-sharing behaviour. First, to promote a knowledge-sharing culture, workplace managers No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s). ORCID Dr Muhammad Waseem Bari 0003-2329-3857 http://orcid.org/0000- KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT RESEARCH & PRACTICE References Abdillah, M. R., Wu, W., & Anita, R. (2022). Can altruistic leadership prevent knowledge-hiding behaviour? Testing dual mediation mechanisms. Knowledge Management Research and Practice, 20(3), 352–366. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/14778238.2020.1776171 Afonso, C., Silva, G. M., Gonçalves, H. M., & Duarte, M. (2018). The role of motivations and involvement in wine tourists’ intention to return: SEM and fsQCA findings. Journal of Business Research, 89(1), 313–321. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.11.042 Anand, P., & Hassan, Y. (2019). Knowledge hiding in orga­ nizations: Everything that managers need to know. Development and Learning in Organizations, 33(6), 12–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/DLO-12-2018-0158 Anser, M. K., Ali, M., Usman, M., Rana, M. L. T., & Yousaf, Z. (2021). Ethical leadership and knowledge hiding: An intervening and interactional analysis. The Service Industries Journal, 41(5–6), 307–329. Bari, M. W., Abrar, M., Shaheen, S., Bashir, M., & Fanchen, M. (2019). Knowledge hiding behaviors and team creativity: The contingent role of perceived mastery motivational climate. SAGE Open, 9(3), 1–15. https://doi. org/10.1177/2158244019876297 Bari, M. W., Ghaffar, M., & Ahmad, B. (2020). Knowledgehiding behaviors and employees’ silence: Mediating role of psychological contract breach. Journal of Knowledge Management, 1(1), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM02-2020-0149 Bari, M. W., Misbah, G., & Bashir, A. (2020). Knowledgehiding behaviors and employees’ silence: Mediating role of psychological contract breach. Journal of Knowledge Management, 24(9), 2171–2194. doi:10.1108/JKM-022020-0149. Bashir, H., Ahmad, B., Bari, M. W., & Khan, Q. U. A. (2021). The impact of organizational practices on formation and development of psychological contract: Expatriates’ percep­ tion-based view. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-10-2020-1187 Bernatović, I., Slavec Gomezel, A., & Černe, M. (2021). Mapping the knowledge-hiding field and its future pro­ spects: A bibliometric co-citation, co-word, and coupling analysis. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 20 (3), 394–409. Blau, P. M. (1964). Social exchange theory. Sage International. http://www.tut.ee/public/m/martmurdvee/EconPsy/5/6._EconPsy_-_Social_exchange.pdf Bogilović, S., Černe, M., & Škerlavaj, M. (2017b). Hiding behind a mask? Cultural intelligence, knowledge hiding, and individual and team creativity. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 26(5), 710–723. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2017.1337747 Bordia, P., Irmer, B. E., & Abusah, D. (2006). Differences in sharing knowledge interpersonally and via databases: The role of evaluation apprehension and perceived benefits. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 15(3), 262–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 13594320500417784 Butt, A. S. (2020). Mitigating knowledge hiding in firms: An exploratory study. Baltic Journal of Management, 15(4), 631–645. https://doi.org/10.1108/BJM-01-2020-0016 Butt, A. S. (2021). Top-down knowledge hiding in buying and supplying firms: Causes and some suggestions. International Journal of Services and Operations Management, 38(2), 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1504/ IJSOM.2021.113030 13 Butt, A. S., & Ahmad, A. B. (2019). Are there any antece­ dents of top-down knowledge hiding in firms? Evidence from the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(8), 1605–1627. https://doi.org/10.1108/ JKM-04-2019-0204 Butt, A. S., & Ahmad, A. B. (2020). Strategies to mitigate knowledge hiding behavior: Building theories from mul­ tiple case studies. Management Decision, 59(6), 1291– 1311. doi:10.1108/MD-01-2020-0038. Černe, M., Hernaus, T., Dysvik, A., & Škerlavaj, M. (2017). The role of multilevel synergistic interplay among team mastery climate, knowledge hiding, and job characteris­ tics in stimulating innovative work behavior. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(2), 281–299. https:// doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12132 Černe, M., Nerstad, C. G. L., Dysvik, A., & Škerlavaj, M. (2014). What goes around comes around: Knowledge hiding, perceived motivational climate, and creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 57(1), 172–192. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.0122 Chaudhry, A., Coyle-Shapiro, J. A. M., & Wayne, S. J. (2011). A longitudinal study of the impact of organiza­ tional change on transactional, relational, and balanced psychological contracts. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 18(2), 247–259. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/1548051810385942 Chen, Y. H., Lin, T. P., & Yen, D. C. (2014). How to facilitate inter-organizational knowledge sharing: The impact of trust. Information and Management, 51(5), 568–578. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2014.03.007 Connelly, C. E., Černe, M., Dysvik, A., & Škerlavaj, M. (2019). Understanding knowledge hiding in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(7), 779–782. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2407 Connelly, C. E., & Kevin Kelloway, E. (2003). Predictors of employees’ perceptions of knowledge sharing cultures. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 24(5), 294–301. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730310485815 Connelly, C. E., & Zweig, D. (2015). How perpetrators and targets construe knowledge hiding in organizations. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(3), 479–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 1359432X.2014.931325 Connelly, C. E., Zweig, D., Webster, J., & Trougakos, J. P. (2012). Knowledge hiding in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(1), 64–88. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/job Crumpton, M. A. (2013). Is the chain of command working for you? The Bottom Line: Managing Library Finances, 26 (3), 88–91. https://doi.org/10.1108/BL-07-2013-0017 Dai, L., & Wang, L. (2016). Psychological contract, recipro­ cal preference and knowledge sharing willingness. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 4(8), 60–76. https://doi.org/10. 4236/jss.2016.48008 de Almeida, F. C., Lesca, H., & Canton, A. W. P. (2016). Intrinsic motivation for knowledge sharing – Competitive intelligence process in a telecom company. Journal of Knowledge Management, 20(6), 1282–1301. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-02-2016-0083 Demirkasımoğlu, N. (2016). Knowledge hiding in academia: Is personality a key factor? International Journal of Higher Education, 5(1), 128–140. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe. v5n1p128 Enwereuzor, I. K., Ugwu, L. E., & Ugwu, L. I. (2022). Unlocking the mask: How respectful engagement enhances tacit knowledge sharing among organizational 14 M. W. BARI ET AL. members. International Journal of Manpower, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-04-2021-0246 Evans, N. (2012). Destroying collaboration and knowledge sharing in the workplace: A reverse brainstorming approach. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 10(2), 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1057/kmrp.2011.43 Fischer, C. (2022). Incentives can’t buy me knowledge: The missing effects of appreciation and aligned performance appraisals on knowledge sharing of public employees. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 42(2), 368–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X20986839 Fong, P. S. W., Men, C., Luo, J., & Jia, R. (2018). Knowledge hiding and team creativity: The contingent role of task interdependence. Management Decision, 56(2), 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-11-2016-0778 Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 002224378101800313 Guest, D. E. (2004). The psychology of the employment relationship: An analysis based on the psychological contract. Applied Psychology, 53(4), 541–555. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2004.00187.x Hair, J. F., Jr, Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equa­ tion modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd) ed.). Hair, J. F., Jr, Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares struc­ tural equation modeling (PLS-SEM).An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128 Han, M. S., Masood, K., Cudjoe, D., & Wang, Y. (2020). Knowledge hiding as the dark side of competitive psy­ chological climate. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 42(2), 195–207. doi:10.1108/ LODJ-03-2020-0090. He, M. R., & Li, Y. J. (2011). An empirical study on the influence of psychological contract types on the tacit knowledge sharing willingness. Journal of Management, 8(1), 56–60. Hernaus, T., Dysvik, A., & Behaviour, O. (2017). The role of multilevel synergistic interplay among team mastery cli­ mate, knowledge hiding, and job characteristics in stimu­ lating innovative work behavior. 27(2), 281–299. https:// doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12132 Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–520. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3. 513 Huo, W., Cai, Z., Luo, J., Men, C., & Jia, R. (2016). Antecedents and intervention mechanisms: A multilevel study of R&D team’s knowledge hiding behavior. Journal of Knowledge Management, 20(5), 880–897. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-11-2015-0451 Johnson, D. W. (2003). Social interdependence: Interrelationships among theory, research, and practice. American Psychologist, 58(11), 934. https://doi.org/10. 1037/0003-066X.58.11.934 Kaya, B., Abubakar, A. M., Behravesh, E., Yildiz, H., & Mert, I. S. (2020). Antecedents of innovative perfor­ mance: Findings from PLS-SEM and fuzzy sets (fsQCA). Journal of Business Research, 114(April), 278–289. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.04.016 Khoreva, V., & Wechtler, H. (2020). Exploring the conse­ quences of knowledge hiding: An agency theory perspective. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 35(2), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-11-2018-0514 Kim, B., Kim, E., Kim, Y., & Cho, J. Y. (2018). Where to find innovative ideas: Interdependence-building mechanisms and boundary-spanning exploration. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 16(3), 376–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2018.1493367 Kingshott, R. P. J. (2006). The impact of psychological con­ tracts upon trust and commitment within supplier – Buyer relationships: A social exchange view. Industrial Marketing Management, 35(6), 724–739. doi:10.1016/j. indmarman.2005.06.006. Koon, V. Y. (2022). The role of organizational compassion in knowledge hiding and thriving at work. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 20(3), 486–501. Kou, C. Y. (2020). Subjective interdependencies in knowl­ edge integration. Knowledge Management Research and Practice, 18(4), 394–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 14778238.2019.1678413 Kourouthanassis, P. E., Mikalef, P., Pappas, I. O., & Kostagiolas, P. (2017). Explaining travellers online infor­ mation satisfaction: A complexity theory approach on information needs, barriers, sources and personal characteristics. Information & Management, 54(6), 814–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2017.03.004 Lee, H., Reid, E., & Kim, W. G. (2014). Understanding knowledge sharing in online travel communities: Antecedents and the moderating effects of interaction modes. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 38 (2), 222–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348012451454 Miminoshvili, M., & Černe, M. (2021). Workplace inclu­ sion–exclusion and knowledge-hiding behavior of min­ ority members. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 20(3), 422–435. Neill, B. S. O., & Adya, M. (2007). Knowledge sharing and the psychological contract stages of employment. 22(4), 411–436. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710745969 Ng, T. W. H., Feldman, D. C., & Butts, M. M. (2014). Psychological contract breaches and employee voice behaviour: The moderating effects of changes in social relationships. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(4), 537–553. https://doi. org/10.1080/1359432X.2013.766394 Olya, H. G. T., & Altinay, L. (2016). Asymmetric modeling of intention to purchase tourism weather insurance and loyalty. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 2791–2800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.11.015 Pan, W., Zhang, Q., Teo, T. S. H., & Lim, V. K. G. (2018). The dark triad and knowledge hiding. International Journal of Information Management, 42(2), 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.05.008 Peng, H. (2013). Why and when do people hide knowledge? Journal of Knowledge Management, 17(3), 398–415. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-12-2012-0380 Perumal, S., & Sreekumaran Nair, S. (2022). Impact of views about knowledge and workplace relationships on tacit knowledge sharing. Knowledge Management Research and Practice, 20(3), 410–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 14778238.2021.1947756 PSEB. (2020). Company Directory. Pakistan Software Export Board. https://pseb.org.pk/app/company_directory.php Ragin, C. C. (2009). Redesigning social inquiry Fuzzy sets and beyond. University of Chicago Press. Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Olya, H. (2021). The combined use of symmetric and asymmetric approaches: Partial least squares-structural equation modeling and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis. KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT RESEARCH & PRACTICE International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(5), 1571–1592. https://doi.org/10.1108/ IJCHM-10-2020-1164 Rihoux, B., & Ragin, C. C. (2008). Configurational compara­ tive methods: Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) and related techniques. Sage Publications. Rousseau, D. M. (1989). Psychological and implied con­ tracts in organizations. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 2(2), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/ BF01384942 Rousseau, D. M. (1996). Psychological contract measures. Carnegie Mellon University. Rousseau, D. M., & Tijoriwala, S. A. (1999). What’s a good reason to change? Motivated reasoning and social accounts in promoting organizational change. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(4), 514–528. Schalk, R., & Roe, R. E. (2007). Towards a dynamic model of the psychological contract. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 37(2), 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 1468-5914.2007.00330.x Schneckenberg, D. (2009). Web 2.0 and the empowerment of the knowledge worker. Journal of Knowledge Management, 13(6), 509–520. https://doi.org/10.1108/ 13673270910997150 Schneider, C. Q., & Wagemann, C. (2010). Standards of good practice in qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) and fuzzy-sets. Comparative Sociology, 9(3), 397–418. https://doi.org/10.1163/156913210X12493538729793 Schneider, C. Q., & Wagemann, C. (2012). Set-theoretic methods for the social sciences: A guide to qualitative comparative analysis. Cambridge University Press. Serenko, A., & Bontis, N. (2016). Understanding counter­ productive knowledge behavior: Antecedents and conse­ quences of intra-organizational knowledge hiding. Journal of Knowledge Management, 20(6), 1199–1224. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-05-2016-0203 Shaheen, S., Bari, M. W., Hameed, F., & Anwar, M. M. (2019). Organizational cronyism as an antecedent of ingratiation: Mediating role of relational psychological contract. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(1), 1–20. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01609 Silva, G. M., & Goncalves, H. M. (2016). Causal recipes for customer loyalty to travel agencies: Differences between 15 online and offline customers. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 5512–5518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jbusres.2016.04.163 Suppiah, V., & Sandhu, M. S. (2011). Organisational cul­ ture’s influence on tacit knowledge-sharing behaviour. Journal of Knowledge Management, 15(3), 462–477. doi:10.1108/13673271111137439. Webster, J., Brown, G., Zweig, D., Connelly, C. E., Brodt, S., & Sitkin, S. (2008). Beyond knowledge sharing: Withholding knowledge at work. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 27(8), 1–37. https:// doi.org/10.1016/S0742-7301(08) Woodside, A. G. (2013). Moving beyond multiple regression analysis to algorithms: Calling for adoption of a paradigm shift from symmetric to asymmetric thinking in data analysis and crafting theory. Journal of Business Re, 66 (4), 463–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.12. 021 Wu, P.-L., Yeh, -S.-S., Woodside, A. G., & Woodside, A. G. (2014). Applying complexity theory to deepen service dominant logic: Configural analysis of customer experience-and-outcome assessments of professional ser­ vices for personal transformations. Journal of Business Research, 67(8), 1647–1670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jbusres.2014.03.012 Xiao, M., & Cooke, F. L. (2018). Why and when knowledge hiding in the workplace is harmful: A review of the literature and directions for future research in the Chinese context. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 57(4), 470–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/17447941.12198 Zhang, L., & Deng, Y. (2014). Guanxi with supervisor and counterproductive work behavior: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Journal of Business Ethics, 134(3), 413–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2438-7 Zhang, Z., & Min, M. (2021). Organizational rewards and knowledge hiding: Task attributes as contingencies. Management Decision, 59(10), 2385–2404. https://doi. org/10.1108/MD-02-2020-0150 Zhang, Y., Ren, T., & Li, X. (2018). Psychological con­ tract and employee attitudes. Chinese Management Studies, 13(1), 26–50. https://doi.org/10.1108/cms-062017-0171