Uploaded by

Tacbobo, April Jean T. - BSME 2B

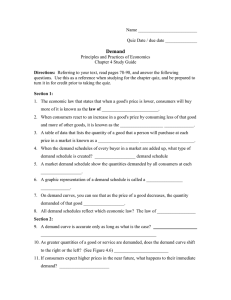

Engineering Economy Principles & Analysis

advertisement

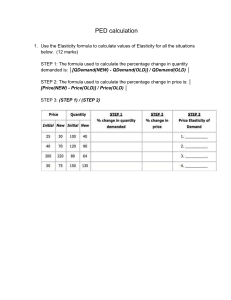

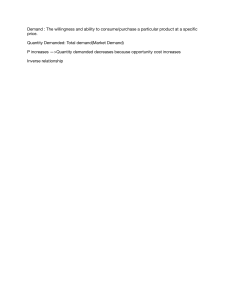

ENGINEERING ECONOMY ENGINEERING ECONOMY Economics Study of how society, i.e. individuals, businesses and government, should allocate scarce resources to the production and distribution of goods and services to the appropriate consumers. ENGINEERING ECONOMY Engineering Economy • • • • involves the systematic evaluation of the economic merits of proposed solutions to engineering problems. To be economically acceptable ( i.e., affordable ), solutions to engineering problems must demonstrate a positive balance of long-term benefits over long-term cost, and must also promote the well-being and survival of an organization, embody creative and innovative technology and ideas, permit identification and scrutiny of their estimated outcomes, and translate profitability to the “ bottom line” through a valid and acceptable measure of merit. ENGINEERING ECONOMY Origins of Engineering Economy The perspective that ultimate economy is a concern to the engineer and the availability of sound techniques to address this concern differentiates this aspect of modern engineering practice from that of the past. • Pioneer: Arthur M. Wellington, civil engineer latter part of nineteenth century; addressed role of economic analysis in engineering projects; area of interest: railroad building • Followed by other contributions which emphasized techniques depending on financial and actuarial mathematics. ENGINEERING ECONOMY Principles of Engineering Economy 1.Develop the Alternatives; • The final choice (decision) is among alternatives. The alternatives need to be identified and then defined for subsequent analysis. 2. Focus on the Differences; • Only the differences in expected future outcomes among the alternatives are relevant to their comparison and should be considered in the decision. ENGINEERING ECONOMY 3. Use a Consistent Viewpoint; • The prospective outcomes of the alternatives, economic and other, should be consistently developed from a defined viewpoint (perspective). 4. Use a Common Unit of Measure; • Using a common unit of measurement to enumerate as many of the prospective outcomes as possible will make easier the analysis and comparison of alternatives. ENGINEERING ECONOMY 5. Consider All Relevant Criteria; • Selection of a preferred alternative (decision making) requires the use of a criterion (or several criteria). The decision process should consider the outcomes enumerated in the monetary unit and those expressed in some other unit of measurement or made explicit in a descriptive manner. 6. Make Uncertainty Explicit; • Uncertainty is inherent in projecting (or estimating) the future outcomes of the alternatives and should be recognized in their analysis and comparison. ENGINEERING ECONOMY 7. Revisit Your Decisions • Improved decision making results from an adaptive process; to the extent practicable, the initial projected outcomes of the selected alternative should be subsequently compared with actual results achieved. ENGINEERING ECONOMY Engineering Economic Analysis Procedure 1.Problem recognition, formulation, and evaluation 2.Development of the feasible alternatives 3.Development of the net cash flow for each alternative 4.Selection of a criterion (or criteria) 5.Analysis and comparison of the alternatives 6.Selection of the preferred alternative 7.Performance monitoring and post evaluation of results ENGINEERING ECONOMY Consumer Goods and Producer Goods and Services Consumer goods and services are those products or services that are directly used by people to satisfy their wants. Food, clothing, homes, cars, television sets, haircut, movies, shoes, medical and dental services are examples. Producer goods and services are used to produce consumer goods and services or other producer goods. Machine tools, factory buildings, buses, and farm machinery are examples. ENGINEERING ECONOMY Necessities and Luxuries Necessities are those products or services that are required to support human life and activities that will be purchased in somewhat the same quantity even though the price varies considerably. Luxuries are those products or services that are desired by humans and will be purchased if money is available after the required necessities have been obtained. ENGINEERING ECONOMY Necessities and luxuries are relative terms, some goods and services are considered as necessity to one person but luxury to another person. For example, a person living in one community may find that an automobile is a necessity to get to and from work. If the same person lived and worked in a different city, adequate public transportation might be available, and an automobile would be a luxury. ENGINEERING ECONOMY Utility and Demand • Utility is a measure of the value which consumers of a product or service place on that product or service; • Demand is a reflection of this measure of value, and is represented by price per quantity of output; ENGINEERING ECONOMY Change in the Demand Schedule Increase or decrease in demand at all price levels, resulting in a right or left shift of the demand curve ENGINEERING ECONOMY The law of Demand The law of demand may be stated as: The demand for a commodity varies inversely as the price of the commodity, though not proportionately. ENGINEERING ECONOMY Elasticity of demand is an important variation on the concept of demand. Demand can be classified as elastic, inelastic or unitary. An elastic demand is one in which the change in quantity demanded due to a change in price is large. An inelastic demand is one in which the change in quantity demanded due to a change in price is small. The formula for computing elasticity of demand is: ENGINEERING ECONOMY • • • • Q1 - stands for quantity demanded before price change. Q2 - stands for quantity demanded After price change P1 - stands for Price Charged before price change. P2 - stands for Price Charged After price change. If the formula creates a number greater than 1, the demand is elastic. In other words, quantity changes faster than price. If the number is less than 1, demand is inelastic. In other words, quantity changes slower than price. If the number is equal to 1, elasticity of demand is unitary. In other words, quantity changes at the same rate as price. ENGINEERING ECONOMY Elasticity of demand is illustrated in Figure 1.4. Note that a change in price results in a large change in quantity demanded. An example of products with an elastic demand is consumer durables. These are items that are purchased infrequently, like a washing machine or an automobile, and can be postponed if price rises. For example, automobile rebates have been very successful in increasing automobile sales by reducing price. ENGINEERING ECONOMY Inelastic demand is shown in Figure 1.5. Note that a change in price results in only a small change in quantity demanded. In other words, the quantity demanded is not very responsive to changes in price. Examples of this are necessities like food and fuel. Consumers will not reduce their food purchases if food prices rise, although there may be shifts in the types of food they purchase. Also, consumers will not greatly change their driving behavior if gasoline prices rise. ENGINEERING ECONOMY Unitary elasticity of demand any change in price causes a proportional change in quantity demanded. For example, a 10% quantity change divided by 10% price change is one. This means that a one percent change in quantity occurs for every one percent change in price. ENGINEERING ECONOMY Competition, Monopoly and Oligopoly Perfect competition occurs in situation where a commodity or service is supplied by a number of vendors and there is nothing to prevent additional vendors entering the market. Under such conditions, there is assurance of complete freedom on the part of both buyer and seller. Monopoly is the opposite perfect competition. A perfect monopoly exists when a unique product or service is available from a single vendor and that vendor can prevent the entry of all others into the market. Under such conditions the buyer is at the complete mercy of the vendor as to the availability and price of thee product. In reality there seldom is a perfect monopoly. Very few products are so rare that substitute cannot be used satisfactory. ENGINEERING ECONOMY Oligopoly exists when there are so few suppliers of a product or service that action by one will almost inevitably result in similar action by others. Thus, if one of the only three oil companies in the country raises the price of gasoline by P0.50 per liter, the other two would undoubtedly do the same because they could do so and still retain their previous competitive positions. ENGINEERING ECONOMY Supply the quantity of a certain price at a given place and time. A rice dealer may have one hundred cavans of rice in his warehouse, but if he only wishes to sell seventy cavans, then, this quantity represents the supply. ENGINEERING ECONOMY ENGINEERING ECONOMY The law of supply and demand The law of supply and demand may be stated as follows: “Under conditions of perfect competition the price at which a given product will be supplied and purchased is the price that will result in the supply and the demand being equal.” ENGINEERING ECONOMY ENGINEERING ECONOMY The Law of Diminishing Returns “When the use of one of the factors of production is limited, either in increasing cost or by absolute quantity, a point will be reached beyond which an increase in the variable factors will result in a less than proportionate increase in output.” ENGINEERING ECONOMY The effect of the law of diminishing returns on the performance of an electric motor is illustrated in Fig.1.11. for the early increase in input, through input of 4.0 kw, the actual increase in output, is greater than proportional; beyond this point the output is less than proportional. In the case the fixed input factor is the electric motor. ENGINEERING ECONOMY END