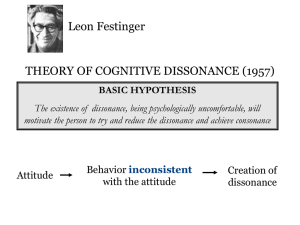

ATTITUDES JONATHAN JONES ATTITUDE STRUCTURE & FUNCTION In this class: §What are attitudes? §How can we measure attitudes? §Where do attitudes come from? §What is the relationship between attitude and behaviour? ATTITUDE: The most distinctive and indispensable concept in contemporary American social psychology Allport, G. W. (1935). Attitudes. In C. Murchison (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 798–844). Worcester, MA: Clark University Press. WHAT IS AN ATTITUDE? §“Mental and neural state of readiness” (Allport, 1935, p. 810) §"Attitudes are likes and dislikes” (Bem, 1970, p. 14) §“A general and enduring positive or negative feeling about some person, object, or issue” (Petty & Cacioppo, 1981, p. 7) WHAT IS AN ATTITUDE? §“The categorization of a stimulus object along an evaluative dimension” (Zanna & Rempel, 1988, p. 319) §“A psychological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favor or disfavor” (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993, p. 1) §“An association in memory between a given object and a given summary evaluation of the object” (Fazio, 1995, p. 247) WHAT IS AN ATTITUDE? §A relatively general and enduring ____________ of an object or concept on a valence dimension ranging from positive to negative §Attitudes are ____________! Fabrigar, L. R., & Wegener, D. T. (2010). Attitude structure. In R. F. Baumeister & E. J. Finkel (Eds.), Advanced social psychology: The state of the science (pp. 177-216). New York: Oxford University Press. WHAT IS AN ATTITUDE? §Preference for or against the attitude object §The good/bad evaluations that we attach to objects in our social world o People, social groups, physical objects, behaviors, abstract concepts Fabrigar, L. R., & Wegener, D. T. (2010). Attitude structure. In R. F. Baumeister & E. J. Finkel (Eds.), Advanced social psychology: The state of the science (pp. 177-216). New York: Oxford University Press. WHAT IS AN ATTITUDE? §Several functions that were ascribed to attitudes have now been reassigned to other cognitive structures §Reduced to its ____________ component Schwarz and Bohner (2001) ATTITUDE MEASUREMENT ____________ measures ____________ measures: Directly asks participants to indicate their attitudes ____________ measures: Infer attitudes without respondents’ awareness of or control over how their attitude is being measured ATTITUDE MEASUREMENT Describe the traits or characteristics of your vacuum cleaner: Useless -2 Unsafe -2 Worthless -2 -1 0 -1 0 -1 0 Useful +1 +2 Safe +1 +2 Valuable +1 +2 ATTITUDE MEASUREMENT Describe your feelings toward spiders: Hateful -2 Tense -2 Disgusted -2 -1 0 -1 0 -1 0 Love +1 +2 Calm +1 +2 Acceptance +1 +2 ATTITUDE MEASUREMENT Issues in the direct measurement of attitudes i.e., self-report measures §Individuals might be unaware of their attitudes §Item presentation (e.g., wording of questions, ordering of items) §Third-person effect §Impression management/Social desirability: Respondents’ reluctance to express some attitudes ATTITUDE MEASUREMENT § Circulation: Roughly 1 Atlantic for every 1 National Enquirer § Google Searches: 1 Atlantic for every 1 National Enquirer § Facebook Likes: ____________ Stephens-Davidowitz, S., & Pabon, A. (2017). Everybody lies: Big data, new data, and what the Internet can tell us about who we really are. New York, NY: HarperCollins. ATTITUDE MEASUREMENT Implicit measures Evaluative priming §Accessibility: The ease with which the attitude can be retrieved from memory Implicit Association Test (IAT): §A reaction time measure that is supposed to assesses how strongly two ideas are associated in memory §Intended to detect subconscious associations TRY IT AT HOME! https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html ATTITUDE MEASUREMENT Implicit measures IAT is ____________! §____________ §Low to moderate correlations between IAT scores and explicit measures are used to suggest the IAT ____________ ____________ §____________ ____________ alone is often sufficient to explain these low correlations! Schimmack, U. (2021). The Implicit Association Test: A method in search of a construct. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(2), 396-414. ATTITUDE MEASUREMENT Implicit measures §Does the IAT reflect subconscious processes? People can predict their IAT scores; correlation of predicted vs. actual IAT scores, r = ____________ §Weak predictor of ____________ (and no better than ____________ measures) Hahn, A., Judd, C. M., Hirsh, H. K., & Blair, I. V. (2014). Awareness of implicit attitudes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(3), 1369–1392. WHERE DO ATTITUDES COME FROM? §AFFECTIVE ORIGINS §COGNITIVE ORIGINS §BEHAVIOURAL ORIGINS §IMPLICIT & EXPLICIT ORIGINS §EVOLUTIONARY ORIGINS Tripartite view: Most theories of attitude formation distinguish between these three sources §GENETIC ORIGINS Olson, M. A., & Kendrick, R. V. (2008). Origins of attitudes. In W. D. Crano & R. Prislin (Eds.), Attitudes and attitude change (pp. 111-130). New York, NY: Psychology Press. WHERE DO ATTITUDES COME FROM? Affective origins A result of the emotional responses that we experience when we encounter an attitude object §Classical & operant conditioning §Mere-exposure effect WHERE DO ATTITUDES COME FROM? Affective origins Classical conditioning: §From pairings between a neutral object and an already positively or negatively evaluated object Operant conditioning: §An association is made between a behavior and a consequence (whether negative or positive*) for that behavior (Hull, 1951; Skinner, 1957; Staats & Staats, 1958) WHERE DO ATTITUDES COME FROM? Affective origins Mere-exposure effect: §Repeated exposure to a stimulus can increase an individual’s positive affect towards it §Average effect of r = 0.26 §Does it replicate? Recent attempt: Chow et al. (2022) found no effect Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9(2, Pt.2), 1–27. WHERE DO ATTITUDES COME FROM? Cognitive origins §A function of one’s beliefs §Beliefs are a product of the expectancy and value attached to each of the perceived attributes of the attitude object §Expectancy: The perceived likelihood that the attribute will occur §Value: One’s evaluation of the attribute BEHAVIOURAL ORIGINS WHERE DO ATTITUDES COME FROM? Behavioural origins §Remember: Most social scientists assume cognition is a precursor of behaviour §However, behaviour can also influence attitudes! §Example: Attitudes based on direct experience are stronger predictors of behaviour §Negative experiences are incorporated faster into our attitudes than positive ones O’Brien, E., & Klein, N. (2017). The tipping point of perceived change: Asymmetric thresholds in diagnosing improvement versus decline. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(2), 161-185. §Interested in understanding how ____________ affected behaviour How did it begin? §In the 1950s, Festinger started doing research on the propagation of rumours Leon Festinger, former Ph.D. student of Kurt Lewin §Festinger became interested in the 1934 Nepal–India Earthquake §Residents from less affected areas experienced high levels of fear §Rumors were spread that even greater disasters were about to hit the villages §Festinger was puzzled: Why are people creating these rumours? §He reasoned rumours were created to justify fear §Insight: People might ____________ ____________ ____________ their current affective state THEORY OF COGNITIVE DISSONANCE THEORY OF ____________ ____________ § A pair of cognitions is inconsistent if one cognition follows from the opposite of the other § ____________ results in a state of discomfort § Individuals are motivated to reduce the ____________ THEORY OF COGNITIVE DISSONANCE To reduce the dissonance, individuals could: §Add consonant cognitions §Subtract dissonant cognitions §Increase the importance of consonant cognitions, or §Decrease the importance of dissonant cognitions §____________ Harmon-Jones, E., & Mills, J. (2019). An introduction to cognitive dissonance theory and an overview of current perspectives on the theory. In E. Harmon-Jones (Ed.), Cognitive dissonance: Reexamining a pivotal theory in psychology (pp. 3–24). American Psychological Association. THEORY OF COGNITIVE DISSONANCE Example §A cigarette smoker: § “I smoke” § “Smoking is harmful to my health” §Contradiction results in ____________ §The person would then engage in attempts to get rid of the ____________ Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson. THEORY OF COGNITIVE DISSONANCE Resolving the dissonance: change his/her beliefs about smoking by… §Adding consonant cognitions: “I believe that smoking reduces tension and keeps me from gaining weight” §Subtracting the dissonant cognition: “Smoking has no harmful effects on health” §Increasing the importance of consonant cognitions: “The enjoyment I get from smoking is a very important part of my life” §Reducing the importance of the dissonant cognition (“trivialization”): “The risk to health from smoking is negligible if compared with the danger of automobile accidents” THEORY OF COGNITIVE DISSONANCE Alternatively, the cigarette smoker could… §Change his behaviour by quitting smoking! THEORY OF COGNITIVE DISSONANCE 1934 Earthquake §Villagers knew there was no rational explanation for the high levels of fear they were experiencing According to ____________ ____________ §Villagers felt fearful (first cognition) §Villagers also knew that there was no reason for fear (contradiction) Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson. THEORY OF COGNITIVE DISSONANCE Rationalizations for the 1934 Earthquake Villagers could eliminate the dissonance by creating a belief and convincing themselves that there was indeed something to fear: §Impending doom was about to strike Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson. THEORY OF COGNITIVE DISSONANCE The total magnitude of dissonance: Where D* equals the total magnitude of dissonance, D equals the sum of all elements dissonant with the element in question, and C equals the sum of all elements consonant with the same element. Nail, P. R., & Boniecki, K. A. (2011). Inconsistency in cognition: Cognitive dissonance. In D. Chadee (Ed.), Theories in social psychology (p. 44–71). Wiley Blackwell. Main Paradigms Used in Dissonance Research §Free-Choice Paradigm §Effort-Justification Paradigm §Belief-Disconfirmation Paradigm §Induced-Compliance Paradigm Harmon-Jones, E., & Mills, J. (2019). An introduction to cognitive dissonance theory and an overview of current perspectives on the theory. In E. Harmon-Jones (Ed.), Cognitive dissonance: Reexamining a pivotal theory in psychology (pp. 3–24). American Psychological Association. Main Paradigms Used in Dissonance Research Free-Choice Paradigm a.k.a. “postdecision spread”: §When people choose between two equally liked alternatives, participants grow to like the chosen item more over time Brehm, J. W. (1956). Postdecision changes in the desirability of alternatives. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 52(3), 384–389. Main Paradigms Used in Dissonance Research Effort-Justification Paradigm: §Hardship influences attitudes §Dissonance is aroused whenever a person puts much effort into achieving some desirable outcome §Dissonance can be reduced by exaggerating the desirability of the outcome Aronson, E., & Mills, J. (1959). The effect of severity of initiation on liking for a group. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 59(2), 177–181. Main Paradigms Used in Dissonance Research Belief-Disconfirmation Paradigm: § Dissonance is aroused whenever people are exposed to information that contradicts their beliefs § To reduce dissonance, people can change their beliefs However, dissonance can also lead to: § Misperception or misinterpretation of the information § Rejection or refutation of the information § Seeking support from those who agree with one’s belief § Attempting to persuade others to accept one’s belief Festinger, L., Riecken, H. W., & Schachter, S. (1956). When prophecy fails: A social and psychological study of a modern group that predicted the destruction of the world. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Main Paradigms Used in Dissonance Research Belief-Disconfirmation Paradigm (cont’d): §Festinger’s infiltration of a UFO cult in 1954 What happened when the there was no flood? §Members who were waiting with other group members maintained their faith §The cult leader reported receiving a message that indicated that the flood had been prevented because of the group’s existence as a force for good §After the disconfirmation, members sought to persuade others of their belief Festinger, L., Riecken, H. W., & Schachter, S. (1956). When prophecy fails. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Main Paradigms Used in Dissonance Research Induced-Compliance Paradigm a.k.a. “forced compliance”: §Dissonance is aroused when a person does or says something that is contrary to a prior attitude §Dissonance can be reduced by changing the attitude to correspond more closely to what was said Learning Theories §Organisms learn by reward and punishment §The greater the reward, the greater the learning THEORY OF COGNITIVE DISSONANCE Festinger and Carlsmith’s (1959) study: §The less participants were paid, the more they said they liked it §Results contradicted learning theories’ framework! §The smaller the reward for saying that the boring task was interesting, the more the participants believed what they had said §The higher the reward, the less they believed it §Effect size: Cohen’s d of ________ Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1959). Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58, 203–210. THEORY OF COGNITIVE DISSONANCE Festinger and Carlsmith’s (1959) study: Does it hold water? §Power: 1 study, n = 20 per cell §Most p-values rounded down §GRIM test: 25% of the reported means are mathematically impossible Matti TJ Heino WHERE DO ATTITUDES COME FROM? Implicit and explicit origins Formation processes of attitudes: §Attitudes formed through a deliberate, thoughtful consideration of attituderelevant information §Attitudes formed through less effortful processes that might occur outside of conscious awareness § “Implicit social cognition” WHERE DO ATTITUDES COME FROM? Implicit and explicit origins §Explicit formation processes: Tend to be more belief-based, cognitive §Implicit formation processes: Tend to be more affective §Origins of implicit attitude: Early life experiences, affective information, “cultural biases", internal pressures to be consistent WHERE DO ATTITUDES COME FROM? Evolutionary origins §Evolutionary psychology: Natural selection creates both anatomical (e.g., shells, spikes) and behavioural adaptations for survival §Human preferences for sweet versus sour foods, “high-fat” vs. “low-fat” desserts, warmth over cold WHERE DO ATTITUDES COME FROM? Genetic origins §Many attitudes have relatively high hereditability indices §Example: Political attitudes are partially heritable, with little effect of shared environment (Olson et al., 2001; Alford, Funk, & Hibbing, 2005) DO ATTITUDES PREDICT BEHAVIOUR? ATTITUDES& BEHAVIOUR §A sociologist traveled throughout the United States with a young Chinese couple §Guests in +250 establishments over 2 years LaPiere, R. T. (1934). Attitudes vs. actions. Social Forces, 13(2), 230-237. ATTITUDES& BEHAVIOUR § Six months later, survey sent to proprietors of each establishment §“Would you accept Chinese nationals as guests?” §128 respondents: § 118 (92%): “______________________________” § 9 (7%): “______________________________” § 1: “______________________________” LaPiere, R. T. (1934). Attitudes vs. actions. Social Forces, 13(2), 230-237. ATTITUDES& BEHAVIOUR Methodological limitations: §No independent ratings of discrimination §Maybe more discrimination if the sociologists hadn't been there? §Only one couple used in the study ATTITUDES& BEHAVIOUR §Wicker (1969): Review of almost 40 studies §Average correlation between attitudes and behaviour: r = _______________ §___________ of the variation in behaviour! Wicker, A. W. (1969). Attitudes versus actions: The relationship of verbal and overt behavioral responses to attitude objects. Journal of Social issues, 25(4), 41-78. ATTITUDES& BEHAVIOUR “Taken as a whole, these studies suggest that it is considerably more likely that attitudes will be _______________ related to overt behaviors than that attitudes will _______________” Wicker, A. W. (1969). Attitudes versus actions: The relationship of verbal and overt behavioral responses to attitude objects. Journal of Social issues, 25(4), 41-78. When do attitudes predict behaviour? It depends on the… §Correspondence between attitudinal and behavioural measures §Domain of behaviour §Function of the attitude §Strength of the attitude §Person §Situation When do attitudes predict behaviour? Correspondence between attitudinal and behavioural measures (i.e., how specific is the measure?) Which attitude has a higher correlation with actual condom use? §“How do you feel about using condoms?” §“_________________________________________ __________________________________?” Sheeran, P., Abraham, C., & Orbell, S. (1999). Psychosocial correlates of heterosexual condom use: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125(1), 90–132. When do attitudes predict behaviour? Domain of behaviour §High correlation between political attitudes and voting behaviour (r = .78) Fazio, R. H., & Williams, C. J. (1986). Attitude accessibility as a moderator of the attitude–perception and attitude–behavior relations: An investigation of the 1984 presidential election. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(3), 505-514. When do attitudes predict behaviour? The function of the attitude §One of the functions of attitudes: Value-expressive § Expressing individual’s central values and self-concept §Attitudes that express core moral values and convictions predict behaviour §Example: Biking to work because you value the environment (being environmentally conscious is part of your self-concept) When do attitudes predict behaviour? The strength of the attitude §Strong attitudes are more likely to predict behaviour than weak ones (Stedman, 2002) When do attitudes predict behaviour? The person (dispositional factors) §How much a person’s behaviour varies across social situations i.e., self-monitoring § Low self-monitoring: Tendency to remain the same across situations § High self-monitoring: People present themselves in a different light depending on the situation (Snyder, 1974, 1986) When do attitudes predict behaviour? The situation §Time constraints §Example: When there are time constraints, Individuals low in self-monitoring are more likely to make decisions based on their attitudes Jamieson, D. A., & Zanna, M. P. (1989). Need for structure in attitude formation and expression. In A. R. Pratkanis, S. J. Breckler, & A. G. Greenwald (Eds.), Attitude structure and function (pp. 383-406). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. ARE ATTITUDES ENOUGH FOR PREDICTING BEHAVIOUR? THEORY OF REASONED ACTION Attitude toward the behaviour: People’s specific attitude toward a behaviour Behavioural Intention Behaviour Subjective norm: People’s perception of the extent to which others who are important to them expect them to engage in a behaviour Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, A. (1975). Beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. THEORY OF Attitude toward the behaviour: People’s specific attitude toward a behaviour Subjective norm: People’s perception of the extent to which others who are important to them expect them to engage in a behaviour Perceived behaviour control: The ease with which people believe they can perform the behaviour PLANNED BEHAVIOUR Behavioural Intention Behaviour Attitudes toward a specific behaviour combine with subjective norms and perceived control to influence a person’s intentions. Intentions, in turn, guide behaviour. Schifter, D. E., & Ajzen, I. (1985). Intention, perceived behavioral control and weight loss: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 843—851. How well does the TPB predict behaviour? §________% of the variance in behavioural intentions §________% of the variance in behaviour §The subjective norm construct is generally the weakest predictor of intentions Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 471–499. Criticism of the TPB §Sniehotta et al. (2014): Size of effects is too small §Kam et al. (2008): Model is too reductionist §Conceptualization and operationalization of the main components of the TPB Giguère, B., Beggs, T., & Sirois, F. (2019). Social cognitive approaches to health issues. In K. O’Doherty & D. Hodgetts (Eds.), The Sage handbook of applied social psychology. Sage. ATTITUDES JONATHAN JONES