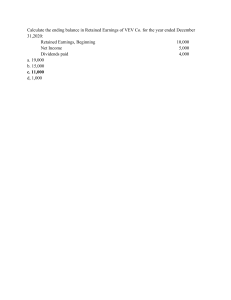

Name: Ellie Ngoc Do Course: Economics of Education 1) Introduction In recent news, many studies have suggested that there is a causal relationship between the quality of education and economic well-being. When talking about the quality of education, we are referring to its return to the economy, which is human capital. At the same time, economic well-being could be for an individual or society as a whole. This paper will discuss the definition of human capital and its role in economic well-being. In addition to explaining this term, this paper will offer the model of capital to shed light on how people make individual investments in human capital as well as the return on education. 2) What is human capital? According to Lovenheim and Turner, human capital refers to all the knowledge, skills, information, and physical capacity of labor that can be used to produce economic values. This might sound similar to physical capital as they both contribute to the production process and produce valuable goods and services. However, this does not mean that humans are capital, or objects ready to be used. Human capital is different from physical capital in the sense that these skills and knowledge are inseparable from the workers and therefore, cannot act as collateral or be exchanged. Even though we tend to take human capital as the equivalent of education because we normally think that formal education is the way to obtain human capital, these two concepts are different. Human capital is not bounded to formal education only. Since, by definition, human capital comprises all knowledge, skills, and physical advantage of labor, formal education, despite being an efficient means of acquiring skills and knowledge, is not the only indicator for good human capital ownership. For example, athletes or artists, who do not have educational degrees but possess outstanding talents and physical capacities, offer a lot of human capital potential that is economically beneficial. However, we cannot deny the causal relationship between education and labor efficiency (human capital) as the return for most of the rest of the population. Human capital is the driving force for economic development in this era because the physical capital and stock of resources are not adequate to account for the economic growth in some nations. There are nations rich in resources, capital, and labor but they cannot utilize all those elements and therefore, do not have the same level of growth compared to nations with more limited resources but acquire higher human capital quality, leading to significant returns in the national economic performance. Thus, human capital would be the most important indicator for the growth of the economy of a nation. 3) Why should we invest in human capital (individual investment decision)? The general common reason for a person to invest in something in the present is that they expect to receive a higher return on their investment in the future, like buying stocks or going to bed early before the day of exams. Using the same reward-favor behavior of humans, the human capital model is designed to explain how the individual current education costs or human capital investment would reward workers with higher future earnings. Students would pursue a certain level of education in order to obtain their desired level of future earnings. In other words, they are accepting the current financial costs of schooling in return for the earning benefit in the future. In essence, this model is a general framework for all individuals to evaluate the costs and benefits of their education decisions, with the costs suffered now and the rewards enjoyed later. The costs and benefits of education investment are plugged into the calculation of this model to project the outcomes of education persuasion. The main benefit of education investment would be the higher incomes earned over the working life. There are many more immeasurable benefits that come with education like social connection, social respect, a higher chance of employment, etc., however, for the simplicity of the model, we will only consider the financial return of education investment, which is the future earnings. The costs of education would involve the direct costs like the actual amount of money an individual spend to finance their learning at an institution, including tuition and textbooks. In addition, education takes time, which is the time that an individual potentially can join the labor market and make income if they did not go to school. The potentially lost wages are another cost of attending school because education requires your full mental and physical participation, which hinders any full-time employment that can earn a significant income. The framework of the human capital model is based on the simple intuition of weighing costs and benefits. If individuals see that their financial spending on education and foregone earnings are relatively less significant to the skills and knowledge they acquire from their education resulting in a higher earning over their working life, they will decide to attend school. However, depending on the skills and level of future income an individual wishes, they also need to decide which type of school and major to pursue. However, as this kind of information is difficult to quantify, the easiest way to access how much a person invests in their education is the number of years attending school and how much they spend on education. The future return would be measured in the number of years they can enjoy the financial reward and how much of the reward they can enjoy. Even though there are many levels of education, the level that makes a significant difference in future earnings is higher education as these are the levels that provide skills and knowledge that are useful and applicable to produce economically valuable goods and services. Therefore, most human capital would measure the years spent on higher education rather than the comprehensive duration of attending school of an individual. This given graph Paulsen shows the costs and benefits of investing in higher education for an average individual who starts college at 18 and pursues a four-year program. The H curve is displaying the growth of income given that the individual has no investment in higher education. Not going to college means the individual does not have to put up with any of the costs but at the same time, they would not have any of the potential rewards and earn a lower level of income. On the other hand, the C curve demonstrates the gain in the income of individuals if they pursue higher education. As we can see for the four years they are in college, they suffer a loss in income due to the direct costs (tuition and expenses) and the indirect costs (forgone earnings) of education, however, they can enjoy a much higher return in earnings which can redeem their education costs. Therefore, using the human capital model, it is a reasonable decision to pursue education if the goal is to earn more in the future. 4) Private and Social Return of Education: As we have discussed the return on education investment is the higher earnings in the future for individuals, but that is not the only possible return. There are two kinds of returning education values: private return and social return. This means that the return of education is not only enjoyed individually but also socially. Individual return refers to the benefits that a person enjoys after their attendance in education. Social return is the type of benefit that society enjoys thanks to the school attendance of an individual. In other words, if a person pursues higher education, not only they be rewarded with high returns, but society would also be better off. For example, a person went through medical school and became a doctor, who makes hundreds of thousands of dollars per year. This doctor, when practicing medicine to make his incredibly high income because of his long years of education, also saves many people. The high salary that this doctor earns is their individual return and the people that they save are the social return from their education. It is a challenging task to clearly separate the two kinds of benefits because they intertwine, inter influence, and interdepend on each other. Economists have chimed in their effort to come up with many studies and formulas to capture or even approximate the share of social and individual returns. For the individual return, some of the prominent methods to measure the Mincer equation which derives the relationship between wages and schooling by accounting for the optimal investment in schooling or the twin studies where the differences in school attainments and earnings between twins were evaluated given that they share the same genetic characteristics. For social return, there is a variety of empirical evidence for this benefit, and the most prominent indicator for this is the national income, or GDP, using the aggregate production function. This function can capture all the social benefits because it was set up to account for all economic activities in a country. If we go back to the doctor example, the number of people they save, after getting treated, will pay their hospital bills, and potentially join the labor force to make income. All these outcomes have a form of economic activity and make their way into this function. There are, of course, a lot of non-economic returns of education like becoming a kind person and a good stay-at-home parent and this function does not give an absolute number on the social return, only a good approximation of how much the society will enjoy with a high level of human capital. This function considers three variables of capital (K), labor (L), and technological advancement (A) in the calculation of national income (Y), which is also the GDP, the Gross Domestic Product. The GDP counts all the new, domestic goods and services produced each year, which acts as a comprehensive measure to evaluate the level of production and economic wellbeing of a country. Technology advances are the innovation that humans that increases the productivity and efficacy of given a fixed amount of labor and capital. The ability to come up with innovations and changes is the knowledge and skills of humans, which are a part of human capital. Therefore, the level of technology variable captures the human capital elements. As we can see in this function, labor and technology advances are considered separately because the level of human capital does not grow if the number of laborers grows given that the laborers do not have any skills or developments that have high social and economic returns. Therefore, given that the over-reproduction of laborers can cause strains on the ability to provide limited resources to the planet, the most sustainable and productive way to increase the level of production is to increase the variable of human capital. Even though education is not the only way to increase human capital and its return, according to the human capital model, it is a reliable way to surely harvest and earn that high level of return by efficiently improving the level of human capital. 5) Conclusion: By using the human capital model, we can see the future return of pursuing higher education is significantly greater than the one with lower education. It also shows that the longer time you spend in education, the more human capital you harvest which contributes to your higher individual return. This demonstrates a clear causal relationship between human capital and education. Although education like going to college is not the only way to gain more human capital, it is a reliable way that is proven to have a sure and high return. This return benefits not only the individual but also the society that they are in. With the aggregate production function, we can see that human capital is crucial to the sustainable growth of an economy. Therefore, this paper is a call for countries to invest more in their education and encourage their citizen to pursue education, which will lead to a higher return for society and the economy. Reference: (1) Lovenheim, M, and Turner, S. (2018). Economics of Education, Macmillan Learning. (2) Paulson, M, & Smart, J (2001), Chap 3, The Economics of Human Capital and Investment in Higher Education, The Finance of Higher Education: Theory, Policy, and Practice.