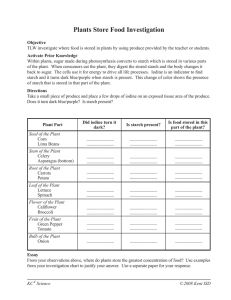

Food Hydrocolloids 143 (2023) 108876 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Food Hydrocolloids journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foodhyd Construction of starch-sodium alginate interpenetrating polymer network and its effects on structure, cooking quality and in vitro starch digestibility of extruded whole buckwheat noodles Xiang Xu, Linghan Meng, Chengcheng Gao, Weiwei Cheng, Yuling Yang, Xinchun Shen, Xiaozhi Tang * College of Food Science and Engineering/Collaborative Innovation Center for Modern Grain Circulation and Safety/Key Laboratory of Grains and Oils Quality Control and Processing, Nanjing University of Finance and Economics, Nanjing, 210023, China A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Keywords: Extruded buckwheat noodle Sodium alginate Interpenetrating polymer network In vitro starch digestibility The effects of different concentrations and crosslinking methods of sodium alginate (SA) on the structure, cooking quality and in vitro starch digestibility of extruded whole buckwheat noodles were investigated. The results showed that SA could interact with starch through hydrogen bonding, resulting in decrease of the relative crystallinity of starch and improvement of thermal stability. Addition of 1% SA significantly decreased the cooking loss from 15.33% to 8.64%, predicted glycemic index (pGI) from 84.76 to 78.92, and increased the noodle hardness from 2260.16 g to 2809.34 g,as well as the content of resistant starch (RS) from 37.25 to 45.47. Two different crosslinking methods, dynamic blending crosslinking (DBC) and in-situ polymerization crosslinking (ISPC) of SA at 1% induced by CaCl2 were attempted to further improve the properties of extruded buckwheat noodle. SEM showed that both starch gel network and SA gel network existed. DBC induced fast gelation of SA molecules, and the aggregated SA gels disrupted the continuity of the starch gel network. As a comparison, SA network was evenly distributed in starch network when ISPC was applied, indicating Starch-SA interpenetrating polymer network (IPN) was successfully constructed. The resultant cooking loss, surface adhesion and pGI value significantly decreased to 6.58%, − 19.59 g s, 69.25, while the noodle hardness and content of RS increased to 6220.90 g, 61.03%, respectively. In a word, the formation of Starch-SA IPN enhanced cooking quality and reduced starch digestibility of extruded whole buckwheat noodles. 1. Introduction Noodle is a type of traditional staple food in Asia, which can be divided into wheat noodles and non-wheat noodles according to the different raw materials (Fu, 2008). Buckwheat is a common grain in daily life. Because it is rich in dietary fiber, polyphenols, flavonoids and various trace elements, long-term consumption can help prevent many chronic diseases. However, extremely low gluten content in buckwheat makes it difficult to be processed into buckwheat noodle by traditional wheat noodle processing methods. Our previous study reported the preparation of whole buckwheat noodles by extrusion processing, leading to the formation of starch gel network instead of gluten protein network to support the shaping of noodles (Sun et al., 2019; Sun, Meng&Tang, 2021; Xu et al., 2022). However, some problems still existed such as long reheating time, high cooking loss, turbid liquid after cooking, high surface viscosity and high starch digestibility of the cooked noodles. Sodium alginate (SA) is an abundant carbohydrate derived from the matrix and cell walls of brown algae (Gao et al., 2021). It has the functions of cation exchange, water absorption and gel filtration in the gastrointestinal tract, which can effectively lower blood lipids and blood pressure, and prevent constipation (Lu, Na, Wei, Zhang&Guo, 2022). SA molecules are composed of different ratios of β-D-mannuronic acid (M-blocks) and α-L-guluronic acid (G blocks) linked by 1–4 glycosidic bonds (Draget & Taylor, 2011). SA can form thermos-irreversible gels at room temperature. The gels are formed by selective binding of alkaline multivalent cations such as Ca2+. The Ca2+ act as a ‘bridge’, by linking a G-block in one alginate molecule to a G-block in another alginate molecule (Lubowa, Yeoh, Varastegan&Easa, 2020). This formed so-called ‘egg-box junction’ in which the Ca2+ fit into the structural void * Corresponding author. College of Food Science and Engineering, Nanjing University of Finance and Economics, Nanjing, 210023, China. E-mail address: warmtxz@nufe.edu.cn (X. Tang). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.108876 Received 5 December 2022; Received in revised form 6 May 2023; Accepted 11 May 2023 Available online 12 May 2023 0268-005X/© 2023 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. X. Xu et al. Food Hydrocolloids 143 (2023) 108876 extrusion process. For DBC, 1% CaCl2 aqueous solution was injected into the extruder instead of water. For ISPC, the extruded buckwheat noodles out of the die immediately immersed in 1% aqueous CaCl2 solution. The sample code and parameters were listed in Table 1. The noodles were dried in a blast drying oven (XMTD-8222, Nanjing David Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd) at 40 ◦ C until the moisture was lower than 12% and sealed with plastic bags for further analysis. Table 1 The parameters of sample preparation. Sample code Concentrations of SA/% Type of solution pumped Type of solution immersed Control 0.5 %SA 1 %SA 2 %SA DBC ISPC 0 0.5 1 2 1 1 water water water water CaCl2 water water water water water water CaCl2 2.3. Characterization DBC: dynamic blending cross-linking; ISPC: in-situ polymerization cross-linking; SA: sodium alginate. 2.3.1. X-ray diffraction measurement (XRD) The crystal structure of starch in extruded buckwheat noodles was studied by X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku, Japan). The freeze-dried buckwheat noodles were ground to powder and passed through a 200mesh sieve. The samples were scanned from 4◦ to 40◦ (2θ) at a scan­ ning rate of 5◦ /min. The test voltage was 40 kV and the current was 30 mA. Relative crystallinity was calculated with MDI Jade 6.5 software (Material Date, Inc. Livermore, California, USA) and expressed as the ratio of the crystalline area to the total area. of SA chains, resembling eggs in an egg box. The structure leads to a strong gel network and helps improve the textural and digestive prop­ erties of the starchy foods. Jang, Bae, and Lee (2015) found that SA can form hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl groups of the starch molecular chains, modifying the rheological and pasting properties and inhibiting activities of digestive enzymes. Kaur, Sharma, Yadav, Bobade, and Singh (2017) added SA to pasta made up with pre-gelatinized brown rice flour and found that both the reheating time and the reheating loss were significantly reduced. In recent years, interpenetrating polymer networks (IPN) have attracted more and more attention due to their great potential in regu­ lating food structure and properties (Ahmad, Ahmad, Manzoor, Pur­ war&Ikram, 2019; Dragan, 2014). Its advantage is that two polymer networks with large differences in physical structure and properties form a stable combination under the action of IPN, and the synergy occurs between the two networks, thereby realizing the performance complementarity (Dragan & Apopei, 2011). SA is an anionic poly­ electrolyte that can form an IPN with other macromolecules through in-situ Polymerization Cross-linking (ISPC) and Dynamic Blending Cross-linking (DBC) induced by divalent cations (Wang, Shan&Pan, 2014). Therefore, we hypothesized that the quality of extruded whole buckwheat noodles could be further improved through constructing starch-SA IPN, which has not been reported yet. In this respect, the ef­ fects of different concentrations of SA and different crosslinking methods for construction of starch-SA IPN on the structure, cooking quality and in vitro starch digestibility of extruded whole buckwheat noodles were investigated in this study. 2.3.2. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) The dried noodles were ground and passed through a 100-mesh sieve. 20 mg of the sample was accurately weighed into a corundum crucible and tested by a thermogravimetric analyzer (NETZSCH STA, Germany NETZSCH Technology Co., Ltd.). An empty crucible was used as a reference under a nitrogen atmosphere. The heating rate was set at 30 ◦ C/min, and the temperature was increased from 25 to 600 ◦ C to obtain the TG curve and the DTG curve. 2.3.3. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) and Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) The cooked noodles were freeze-dried for 72 h and cut into 3 mm long sections and fixed on the tray, the cross-section and sides were sputtered with gold-palladium alloy and observed by a scanning elec­ tron microscope (ZEISS Gemini 300, Carl Zeiss AG). The accelerating voltage was 30 kV, and the pictures were taken using 600 × , 1000 × and 2000× magnifications. The appropriate SEM images were selected for EDS analysis to determine the distribution of C element, Ca element and Na element. 2.3.4. Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) 0.1 g of dried noodles was accurately weighed and mix with 5 mL HNO3 (65%, excellent grade) and 2 mL H2O2 (30%, excellent grade) into a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) container. The samples were decom­ posed in a microwave digestion apparatus (Mars 6 Classic, CEM, USA) after standing for 2 h. The microwave digestion steps were as follows: the samples were heated to 130 ◦ C for 10 min and kept for 5 min, then heated to 160 ◦ C for 5 min and kept for 15 min, finally cooled for 15 min. The digested samples were diluted to 50 mL with high-purity deionized water after cooling. The concentrations of Na and Ca elements were determined using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICPMS) (7700Xx, Agilent Technologies, USA). The specific operating pa­ rameters of the instrument were as follows: the auxiliary gas flow rate was 1.0 L s− 1, and the speed of the peristaltic pump was 0.1 r⋅s− 1. The radio frequency power was 1550 W, and the temperature of the spray chamber was 2 ◦ C. The signal integration time was 0.09 s. The reagent blank solution was prepared according to above steps, and all experi­ ments were performed in triplicate. 2. Materials and methods 2.1. Materials The buckwheat grains were purchased from Yanzhifang Food Co., Ltd (Anhui, China), and crushed by an ultrafine centrifugal crusher (ZM 200, Retsch, Germany) and then passed through 60 mesh sieves. Sodium Alginate (SA) and maleic acid were purchased from Shanghai McLean Biological Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The CaCl2 and NaCl were purchased from Xilong Science Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). The α-amylase (10065; ≥30 U/mg), gastric Protease (P700; 800–2500 U/mg) and Pancreatin (P7545; 8X USP) were purchased Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The amyloglucosidase (3260 u/mL) and GOPOD reagent buffer was purchased from Megazyme (Ireland); Maleate con­ sisted of an equal volume of 0.1 mol/L maleic acid and 0.15 mol/L NaCl and was adjusted to the pH of 6.0 with solid NaOH. The other chemicals and reagents used in this study were at least of analytical grade. 2.2. The preparation of noodles 2.3.5. Cooking quality The cooking quality of noodles including the optimal cooking time and the cooking loss were determined According to the method of Fu et al. (2020) with slight modification. The optimal cooking time: 10 g of noodles were put in a beaker containing about 300 mL of boiling distilled water. When the hard core of the noodles disappeared, it was considered that the noodles had reached the optimal cooking time. According to the description of Sun et al. (2019), a twin-screw extruder (Brabender DSE 20/40, Germany) was used to prepare the extruded whole buckwheat noodles. The different concentrations (0.5%, 1%, 2%) of SA (w/w) was evenly mixed with the buckwheat flour. The water was injected into the extruder by a plug pump during the 2 X. Xu et al. Food Hydrocolloids 143 (2023) 108876 Fig. 1. The XRD picture (A) and Relative crystallinity (B) of extruded buckwheat noodles with different SA concentrations and crosslinking methods. Values followed by different letters in the figure are significantly different (n = 3, p < 0.05). DBC: dynamic blending cross-linking; ISPC: in-situ polymerization cross-linking; SA: sodium alginate. The cooking loss: After the buckwheat noodles were boiled at the optimal cooking time, the liquid left over from cooking the noodles was collected and volume up to 500 mL with deionized water in volumetric flask, and then dried at 105 ◦ C for 12 h. The cooking loss was calculated as the ratio of the weight of solids lost in the noodle soup to that of dried noodle. (resistant starch) according to the methods described by Sun et al. (2019). 2.3.9. Statistical analysis Statistical analysis of the data was performed using SPSS (version 24, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). Differences in means were determined by Duncan’s multiple range test and p<0.05 was considered to be statis­ tically significant throughout the study. All measurements were per­ formed in triplicate unless specifically described. 2.3.6. Turbidity The turbidity of liquid left over from cooking the noodles was measured by a turbidity meter (WGZ-2000, Shanghai Yidianwuguang Co., Ltd.). Each test was replicated four times. 3. Results and discussion 2.3.7. Texture properties The texture properties were evaluated by texture profile analysis (TPA) using a TA-XT 2i texture analyzer (TA-XT 2i, Stable Micro Sys­ tems, Godalming, Surrey, U.K.). Three strips of cooked noodles were parallelly placed on a flat plate and compressed to 75% of the original height at a speed of 1 mm/s using the probe P/36 R. Measurements were performed with six replicates. 3.1. XRD analysis The XRD patterns can reflect the order degree of molecular rear­ rangement after starch gelatinization. Larger relative crystallinity rep­ resented higher degree of order (Li, Wang, Chen, Liu&Li, 2017). Fig. 1 showed the XRD patterns of different extruded noodle samples and their relative crystallinity (RC) values. It can be found that the extruded buckwheat starch had strong peaks at 12.9◦ and 19.8◦ (Fig. 1A). The peak at 19.8◦ represented the complex formed by amylose and buck­ wheat lipids (Hoover&D. Hadziyev, 1981). Pure SA had a peak at 31.8◦ , but there was no peak near 31.8◦ for the noodle samples. It may be attributed to good compatibility between buckwheat starch and SA. SA was bound to starch through hydrogen bonding, which affected the crystal structure of SA. By calculating the RC value of each sample (Fig. 1B), the RC values of noodles decreased from 19.34% to 16.27% after adding SA from 0% to 2%. Similar results were also reported by Zhao et al. (2020). This indicated that the rearrangement of starch molecules was hindered by the addition of SA. The rearrangement of starch molecules was essentially the formation of hydrogen bonds within and between starch molecular chains, which changed the starch molecules from amorphous to crystalline state. SA could connect with the hydroxyl groups on the starch molecular chains through hydrogen bonding, inhibiting the hydrogen bonding interactions within the starch molecules; In addition, SA affected the water distribution and acted as a steric hindrance on starch recrystallization, which was reported by Yu, Wang, Chen, and Li (2018), who added SA into potato starch and found that the crystallinity of potato starch decreased by 3.97% after 21 days of storage. Hong, Zhang, Xu, Wu, and Xu (2021) also found that the inhibition of the starch retrogradation by SA was attributed to its re­ striction of water mobility in the gel matrix. The low mobility of water restricted the migration of starch chains and hindered the formation of crystallization. There was no significant difference (p < 0.05) in the relative 2.3.8. In vitro starch digestibility In vitro starch digestibility was tested according to Goh et al. (2015) and Woolnough, Bird, Monro, and Brennan (2010), including three stages of simulated oral, gastric and pancreatic digestion. 2.5 g of cooked and chopped noodles were put in a conical flask with 30 mL of distilled water and then placed in a shaking water bath at 37 ◦ C (130 r/min). The oral phase was initiated by adding 0.1 mL of 10% α-amylase solution and stopped by adding 0.8 mL of 1 moL/L HCl after 1 min. Then 1 mL of 10% gastric protease solution in 0.05 moL/L HCl was added to initiate the gastric digestive phase and stopped by adding 2 mL of 1 moL/L NaHCO3 solution and 5 mL of 0.2 moL/L maleate (pH 6.0) after 30 min. Finally, 0.1 mL of amyloglucosidase was added to prevent the final product (maltose) from inhibiting trypsin, and 1 mL of 5% pancreatin was added to initiate the pancreatic digestion stage. The reaction mixture was volumed up to 55 mL with the distilled water and 1 mL of the solution was added to a centrifuge tube containing 4 mL of absolute ethanol at 0 (before adding the enzyme), 20, 60, 120 and 180 min. The centrifuge tube was centrifuged at 3000 r/min for 10 min, and 0.1 mL of the su­ pernatant was taken to measure the glucose concentration with D-glucose kit. Data obtained from the test was fitted by a non-linear model to describe starch hydrolysis kinetics and parameters like C∞ (calculated equilibrium concentration), k (kinetic constant), AUC (area under hy­ drolysis curve), HI (hydrolysis index), pGI (predicted glycemic index), RDS (rapidly digested starch), SDS (slowly digested starch) and RS 3 X. Xu et al. Food Hydrocolloids 143 (2023) 108876 Fig. 2. The pictures of the weight loss (A) and the DTG (B) of different SA concentrations and crosslinking methods on extruded buckwheat noodles. DBC: dynamic blending cross-linking; ISPC: in-situ polymerization cross-linking; SA: sodium alginate. crystallinity between the DBC and 1% SA, which were 17.90% and 17.80%, respectively. The relative crystallinity of ISPC further decreased to 16.58%, indicating that SA gel network cross-linked by in-situ poly­ merization might affect the starch gel network and inhibit the rear­ rangement of starch chains. starch gel network. With the addition of SA, the starch gel network structure became compact and the cross-linking sites between SA and starch could be clearly seen. When the concentration of SA was 1%, the crosslinking sites were relatively evenly distributed in the starch gel network, which would strengthen the noodle structure. However, the internal network structure was obviously destroyed when SA concen­ tration reached 2%. This showed that excessive SA might lead to the discontinuity of the original starch network of buckwheat noodles by formation of a large amount of hydrogen bonding interactions with starch molecules. Similar results could also be seen from the side view of extruded and boiled noodles in Fig. 3B and C. For ISPC, Fig. 4B clearly showed that there were many uniform and fine SA crosslinking site distributed in the starch gel network. The starch gel network was interwoven with the SA gel network, indicating the formation of an interpenetrating polymer network structure. As a compare, DBC induced fast gelation and crosslinking of SA molecules. The aggregated SA gels might disrupt the continuity of the starch gel network. As shown in Fig. 3 A-C, exhibiting the irregular cross-linking sites and cracks. In order to illuminate the distribution of SA gel network in the starch gel network, EDS elemental analysis was performed on extruded noodles of ISPC and DBC, and the element content was determined by ICP-MS. The results were shown in Fig. 4A (DBC) and 4B (ISPC). It could be clearly seen that there was mutually interspersed polymer network structure existed in the cross-section of the noodle for ISPC, which could not be observed in the cross-section of noodle for DBC. However, the blue dots represented Ca elements in Fig. 4A and B. The distribution of Ca elements in DBC showed aggregation obviously, while the distribu­ tion of Ca elements in ISPC was more uniform. By ICP-MS determina­ tion, the content of Ca and Na in DBC were 0.221% and 0.095%, respectively, while the content of Ca and Na in ISPC were 0.172% and 0.080%, respectively. It is reported that SA could form hydrogel network upon contact with Ca2+, which had been described as an “egg-box junctions” between G-blocks and Ca2+ (Deszczynski, Kasapis, Mac­ Naughton&Mitchell, 2003). As a result, Ca2+ replaced Na + originally existed in SA. Therefore, the distribution of the SA gel network could be indirectly demonstrated by the distribution of Ca elements. Compared with DBC, the content of Na element in ISPC was lower, which indicated that the SA network of ISPC was more sufficiently formed due to the replacement of Na+ with Ca2+ and the formation of IPN structure be­ tween the starch gel network and the SA gel network was further confirmed in ISPC from Fig. 4A and B. Based on the above, a starch-SA IPN in the extruded buckwheat noodle could be constructed through ISPC, while the DBC induced an aggregated SA crosslinking gel, which disrupted the continuity of the starch gel network. For ISPC,1% SA was first evenly distributed in the starch gel network during extrusion. Then Ca2+ entered into the starch gel network and acted as a cross-linking agent to form SA gel network 3.2. TG analysis TGA curves were shown in Fig. 2A. It could be seen that the thermal decomposition of extruded noodles mainly had three stages. The first stage was T ≤ 150 ◦ C, which was mainly the escape of moisture and volatile substances in the sample; The second stage was 250 ◦ C ≤ T ≤ 370 ◦ C, which was mainly caused by the rapid dehydration and decomposition of the hydroxyl groups of the glucose rings. In this stage, the C–C–H, C–O and C–C bonds were broken, and the main chains were also broken; the third stage was T > 450 ◦ C, this stage was mainly due to the carbonization of starch (Pineda-Gómez, Coral, Ramos-Rivera, Rosales-Rivera&Rodríguez-García, 2011). From Fig. 2A, the thermal decomposition temperature of extruded noodles did not change after adding SA, indicating that SA and starch had good compatibility, and SA could be evenly distributed in the starch gel network of noodles. The residual mass of SA was the highest after calcining at 600 ◦ C, which was 29.49%. It might be due to the carbonization of SA after pyrolysis and the formation of a carbonaceous residue, which finally yielded Na2CO3 (Siddaramaiah Swamy, Ramaraj, & Lee, 2008). The residual mass of the control was 11.99%. After adding 1% SA to the buckwheat noodles, the residual mass of the noodles increased to 14.57%. This might be attributed to that SA was combined with buckwheat starch through hydrogen bonding, which improved the thermal stability of buckwheat starch. DBC and ISPC further increased the residual mass to 18.27% and 19.68%, respectively. The DTG curves were shown in Fig. 2B. The maximum thermal decomposition rate of SA was higher than that of control, and addition of SA increased the decomposition rate of the extruded noodles. There was no significant difference in the thermal decomposition rate between the DBC and the noodles with 1% SA. However, the thermal decomposition rate of ISPC significantly decreased, indicating that SA might form SA gel network by in-situ Polymerization Cross-linking, which affected the starch gel network and improved its thermal stability. 3.3. SEM and element distribution analysis SEM analysis was performed to explore the effects of the SA con­ centration and the cross-linking methods on the microstructure of extruded buckwheat noodles, Fig. 3A was the cross-sectional view of extruded noodles. From Fig. 3A, the cross-section of the control buck­ wheat noodles presented porous structure indicating the formation of 4 X. Xu et al. Food Hydrocolloids 143 (2023) 108876 Fig. 3. The SEM images of SA with different concentrations and crosslinking methods of extruded buckwheat noodles. A is the cross-sectional view of extruded noodles at 5000 times magnification, B is a side view of the extruded noodles at 600 times magnification, C is a side view of the cooked noodles at 300 times magnification. DBC: dynamic blending cross-linking; ISPC: in-situ polymerization cross-linking; SA: sodium alginate. 5 X. Xu et al. Food Hydrocolloids 143 (2023) 108876 Fig. 4. The EDS layered images of SA with different crosslinking methods of extruded buckwheat noodles. A is DBC, B is ISPC. DBC: dynamic blending cross-linking; ISPC: in-situ polymerization cross-linking; SA: sodium alginate. 6 X. Xu et al. Food Hydrocolloids 143 (2023) 108876 with starch network and even destroyed the continuity of the starch network. 3.4. Cooking quality analysis The optimal cooking time and the cooking loss are important in­ dicators for evaluating the cooking quality of noodles. From Fig. 5, the optimal cooking time of the noodles decreased from 4.67 min to 3.83 min after adding SA. This might be due to that SA itself had a large number of hydroxy groups with strong hydrophilicity. The water could quickly enter the noodles and shorten the rehydration time. Kaur et al. (2017) also found that SA could shorten the optimal cooking time of pasta. When the concentration of SA was greater than 1%, the cooking time did not change significantly. The cooking loss of noodles decreased significantly with the addition of SA (p < 0.05) and the lowest value was 8.64% when the concentration of SA was 1%. This was attributed to the formation of Hydrogen bonds between SA and starch molecules, which fixed free amylose fragments and reduced the amount of starch dissolved during the cooking of noodles (Córdoba, Cuéllar, González&Medina, 2008), When the SA concentration was 2%, the cooking loss rose to 10.03%. It might be because too much SA weakened the starch gel network as shown in SEM analysis. After cross-linking SA in different ways, the optimal cooking time and cooking loss of noodles greatly changed. For ISPC, the optimal cooking time and cooking loss reduced to 3.89 min and 6.58%, respec­ tively. However, for DBC, a higher cooking time of 4.39 min and cooking loss of 14.26%, were obtained. This might be because the aggregated SA gel in DBC destroyed the continuity of the starch gel network. However, for ISPC, a starch-SA IPN structure was formed, which could well protect the broken starch fragments and other free components in the noodles, resulting in a significant reduction in the cooking loss. Fig. 5. The effects of SA with different concentrations and crosslinking methods on cooking time and cooking loss of extruded buckwheat noodles. Values followed by different letters in the figure are significantly different (n = 3, p < 0.05). DBC: dynamic blending cross-linking; ISPC: in-situ polymerization crosslinking; SA: sodium alginate. during the immersion of extruded noodle in CaCl2 solution as the second network. This was through chain–Ca2+–chain interactions, and the two network could be well interwoven to form an IPN. Nevertheless, In DBC, direct injection of CaCl2 would rapidly induce SA to form a gel in the extruder due to the fast rate of cross-linking reactions when SA con­ tacted Ca2+. Too fast gel formation rate would lead to SA aggregation obviously, and a uniform gel with a good three-dimensional network structure could not be obtained (Ensor, Sofos&Schmidt, 1990). As a result, the aggregated SA network in the noodles could not form an IPN Fig. 6. The effect of SA with different concentrations and crosslinking methods on the liquid left after cooking noodles. DBC: dynamic blending cross-linking; ISPC: in-situ polymerization cross-linking; SA: sodium alginate. 7 X. Xu et al. Food Hydrocolloids 143 (2023) 108876 Fig. 7. The effects of SA with different concentrations and crosslinking methods on Hardness, Elasticity (A), Resilience and Adhesiveness (B) of extruded buckwheat noodles. Values followed by different letters in the figure are significantly different (n = 3, p < 0.05). DBC: dynamic blending cross-linking; ISPC: in-situ polymerization cross-linking; SA: sodium alginate. 3.5. Turbidity analysis The turbidity of the liquid left over from cooking noodles was also the indicator to evaluate the quality of the noodles. Fig. 6 showed that the cloudy liquid could be observed for the control and the turbidity reached 13.03 NTU. With the addition of SA, the liquid became clearer and the turbidity decreased from 1.34 NTU to 0.75 NTU. When noodles were cooked, broken starch fragments and some loosely bound gelati­ nized starch dissolved, resulting in a cloudy noodle soup. The formation of hydrogen bonds between SA and buckwheat starch molecular chains helped fix the broken starch fragments (Ramírez et al., 2015), decreasing the turbidity of the liquid left over from cooking noodles. Yu, Wang, Chen, and Li (2018) also found that the hydrocolloids helped decrease the turbidity of the liquid left over from cooking wheat noo­ dles. DBC increased the turbidity to 10.93 NTU, while ISPC further decrease turbidity to 0.23 NTU. This indicated that the formation of starch-SA IPN structure in ISPC could better protect the free starch fragments and other easily soluble substances, which was corresponded very well with results of cooking loss of the noodles. Fig. 8. In vitro hydrolysis curve of SA with different concentrations and crosslinking methods on the extruded buckwheat noodles. DBC: dynamic blending cross-linking; ISPC: in-situ polymerization crosslinking; SA: sodium alginate. 3.6. Texture analysis The edible quality of noodles can be reflected by the texture prop­ erties. For example, the hardness of TPA usually represents the force required by the teeth to squeeze the noodle, and the elasticity represents the degree to which the noodles can recover after being compressed once, and the adhesiveness reflects the smoothness of the noodles when eaten (Xu et al., 2022). Usually, noodles with high adhesiveness are easy to stick together during cooking, resulting in insufficient cooking of noodles (Hong et al., 2019). The texture properties of extruded buck­ wheat noodles were shown in Fig. 7. With the addition of SA, the hardness of the noodles first increased and then decreased, while the elasticity continuously decreased. There was no significant difference in recovery and adhesiveness (p < 0.05). This might be because the addi­ tion of a small amount of SA could strength of the starch gel network, while the excessive amount of SA (2%) would weaken the starch gel network (as shown in Fig. 3C). Jang et al. (2015) also found that the hardness of the noodles decreased from 1145.00 g to 1018.41 g after adding 2% SA into the buckwheat noodles. After cross-linking SA in different ways, the texture properties of noodles significantly changed. From Fig. 7, the hardness and recovery of the ISPC increased significantly, reaching 6220.9 g and 0.41, respec­ tively, while the adhesiveness decreased significantly to − 19.59 g s. In contrast, the hardness of the DBC decreased significantly, and the sur­ face adhesion increased slightly, to 2149.27 g and − 43.02 g s, respec­ tively. It could be seen from SEM that the DBC led to local aggregation of SA, which not only failed to interpenetrate with the starch gel network, but also destroyed the continuity of the original starch gel network in the noodles. Therefore, the support force of the starch gel network was also weakened. Moreover, the uneven cross-linking also led the free starch fragments to adhere to the surface of the noodles after cooking, resulting in the increasing of the adhesiveness of the noodles (Nitta et al., 2018). The starch gel network and SA gel network constructed in the ISPC could interpenetrate well, and the two networks supported each other and showed a synergistic effect. Therefore, the hardness of the noodles increased significantly, and the adhesion was greatly reduced. 3.7. In vitro digestibility analysis In vitro hydrolysis curves are commonly used to simulate in vivo digestion processes and predict glycemic index (Goni, Garcia-AIonso, & Saura-Calixto, 1997). Fig. 8 was the digestion curve of extruded buck­ wheat noodles. The starch hydrolysis rate increased rapidly within 0–20 min and began to increase slowly after 20 min in all samples. The addition of SA made the starch hydrolysis rate of the extruded buck­ wheat noodles significantly lower than that of the control. However, with the further increase of SA concentration to 2%, the starch 8 X. Xu et al. Food Hydrocolloids 143 (2023) 108876 Table 2 The effects of SA with different concentrations and crosslinking methods on calculated equilibrium concentration (C∞), enzymatic hydrolysis speed rate (k), hydrolysis index (HI), predicted glycemic index (pGI) and in vitro starch digestion fraction on the extruded buckwheat noodles. Sample number Control 0.5 %SA 1 %SA 2 %SA DBC ISPC K/(s− 1)b C∞/% 62.34 60.18 53.96 59.63 54.26 38.13 d ± 0.13 ± 0.06c ± 0.21b ± 0.42c ± 0.72b ± 0.32a 0.033 ± 0.032 ± 0.034 ± 0.031 ± 0.037 ± 0.053 ± 0.000a 0.006a 0.000a 0.005a 0.001a 0.001b AUC 93.64 89.25 81.51 88.06 83.00 61.40 HI/% ± 0.33d ± 3.53c ± 0.20b ± 3.07c ± 0.57b ± 0.33a 82.05 78.21 71.42 77.17 72.73 53.81 pGI ± 0.29d ± 3.09c ± 0.18b ± 2.69c ± 0.50b ± 0.29a 84.76 ± 82.65 ± 78.92 ± 82.08 ± 79.64 ± 69.25 ± RDS/% 0.16d 1.70c 0.10b 1.48c 0.27b 0.16a 35.17 ± 34.57 ± 31.49 ± 33.54 ± 30.74 ± 26.04 ± SDS/% 0.00e 0.59e 0.61c 0.28d 0.00b 0.00a 27.64 26.18 23.04 25.97 22.79 12.94 ± 0.45d ± 0.00c ± 0.77b ± 0.28c ± 1.56b ± 0.41a RS/% 37.25 39.25 45.47 40.49 46.47 61.03 ± 0.45a ± 0.59b ± 0.15c ± 0.00b ± 1.56c ± 0.41d Values are expressed by means ± standard deviation and the different letters in the same column indicate significant differences (n = 3, p < 0.05). RDS: rapidly digestible starch; SDS: slowly digestible starch; RS: resistant starch; DBC: dynamic blending cross-linking; ISPC: in-situ polymerization cross-linking; SA: sodium alginate. hydrolysis of buckwheat noodles increased. This might be because the high concentration of SA weakened the starch gel network. The digestive enzymes were easier to contact with the starch and led to the increasing of the starch hydrolysis rate. Ramírez et al. (2015) found that there was a critical concentration that affected the starch hydrolysis rate between 1% and 2% SA addition. Dartois, Singh, Kaur, and Singh (2010) reported that guar gum could form a continuous physical barrier on the surface of starch granules when studying the interaction between guar gum and starch, reducing the contact between enzymes and starch and inhibiting starch hydrolysis. To be noted, the hydrolysis rate of buckwheat noodles was further reduced after the IPN was constructed in ISPC, which showed great potentials for developing low glycemic index foods. Table 2 was the fitting data of the hydrolysis kinetics depicted by the nonlinear model. As shown in the table, the calculated equilibrium concentration (C∞), hydrolysis index (HI) and predicted glycemic index (pGI) of the extruded buckwheat noodle first decreased and then increased with the addition of SA, and both were significantly lower than the control. The pGI value significantly decreased from 84.76 to 78.92 after adding SA. For ISPC, the pGI value further decreased to 69.25. However, the pGI value of DBC was 79.64, which was even higher than the noodles with 1% SA. It further proved that the construction of the IPN in ISPC played a better physical barrier function, and reduced the contact of starch with digestive enzymes, thus decreasing the pGI value. The content of rapidly digestible starch (RDS), slowly digestible starch (SDS) and resistant starch (RS) in buckwheat noodles were also shown in Table 2. After adding SA, the RDS and SDS of noodles were lower than that of the control, but the RS was significantly higher than that of the control. The RDS and SDS of noodles reached the lowest values of 31.49% and 23.04% and RS of 45.47% when the SA content was 1%. After the construction of the IPN in the buckwheat noodles, the RDS and SDS were reduced to 26.04% and 12.94%, respectively, and the RS content was increased to 61.03%, indicating that the construction of the starch-SA IPN could convert RDS and SDS into RS. The formation of the IPN could better play its role as a physical barrier, which prevented starch from being hydrolyzed in digestive enzymes (Cui et al., 2022). hindered the contact of starch with digestive enzymes. The pGI value of noodles decreased to 69.25, and the content of resistant starch increased to 61.03%. Therefore, this IPN structure has great potential in the development of low GI and high-quality starch-based noodles. Credit authorship contribution statement Xiang Xu: Conceptualization, Methodology, data analysis, Investi­ gation and Writing-Original draft. Linghan Meng: Conceptualization, supervision, Writing - Review and Editing. Chengcheng Gao: data analysis, graph preparation, Writing - Review and Editing. Weiwei Cheng: data analysis. Yuling Yang: supervision. Xinchun Shen: su­ pervision. Dr. Xiaozhi Tang: Conceptualization, supervision, Writing Review and Editing. Declaration of competing interest We declare that we have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work, there is no commercial or organization conflict of interest in the work we have submitted. Data availability Data will be made available on request. Acknowledgements The authors thank the support from the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD), China. References Ahmad, S., Ahmad, M., Manzoor, K., Purwar, R., & Ikram, S. (2019). A review on latest innovations in natural gums based hydrogels: Preparations & applications. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 136, 870–890. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.06.113 Córdoba, A., Cuéllar, N., González, M., & Medina, J. (2008). The plasticizing effect of alginate on the thermoplastic starch/glycerin blends. Carbohydrate Polymers, 73(3), 409–416. https://doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2007.12.007. Cui, C., Li, M., Ji, N., Qin, Y., Shi, R., Qiao, Y., et al. (2022). Calcium alginate/curdlan/ corn starch@calcium alginate macrocapsules for slowly digestible and resistant starch. Carbohydrate Polymers, 285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. carbpol.2022.119259. Article 119259. Dartois, A., Singh, J., Kaur, L., & Singh, H. (2010). Influence of guar gum on the in vitro starch digestibility—rheological and microstructural characteristics. Food Biophysics, 5(3), 149–160. https://doi:10.1007/s11483-010-9155-2. Deszczynski, M., Kasapis, S., MacNaughton, W., & Mitchell, J. R. (2003). Effect of sugars on the mechanical and thermal properties of agarose gels. Food Hydrocolloids, 17(6), 793–799. https://doi:10.1016/S0268-005X(03)00100-0. Dragan, E. S. (2014). Design and applications of interpenetrating polymer network hydrogels. A review. Chemical Engineering Journal, 243, 572–590. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cej.2014.01.065 Dragan, E. S., & Apopei, D. F. (2011). Synthesis and swelling behavior of pH-sensitive semi-interpenetrating polymer network composite hydrogels based on native and modified potatoes starch as potential sorbent for cationic dyes. Chemical Engineering Journal, 178, 252–263. http://doi:10.1016/j.cej.2011.10.066. 4. Conclusion This study explored the effects of addition of SA and SA crosslinking methods on the quality characteristics of extruded buckwheat noodles. The results showed that SA could be combined with buckwheat starch through hydrogen bonding, reducing the relative crystallinity of buck­ wheat starch and improving thermal stability. However, excessive SA could destroy the continuity of starch gel network. Adding 1% SA could effectively reduce the cooking loss and pGI value of the noodles. DBC induced fast gelation and aggregation of SA, which disrupted the con­ tinuity of the starch gel network. Compared with DBC, SA could form an IPN with the starch gel network through ISPC. The two networks sup­ ported each other and exhibited a synergistic effect, further improving the thermal stability and hardness of the noodles and reducing the cooking loss, turbidity, surface adhesion. In addition, the IPN structure 9 X. Xu et al. Food Hydrocolloids 143 (2023) 108876 Draget, K. I., & Taylor, C. (2011). Chemical, physical and biological properties of alginates and their biomedical implications. Food Hydrocolloids, 25(2), 251–256. http://doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2009.10.007. Ensor, S.a., Sofos, J.n., & Schmidt, G.r. (1990). Otimization of algin/calcium binder in restructured beef. Journal of Muscle Foods, 1, 197–206. Fu, X. B. (2008). Asian noodles: History, classification, raw materials, and processing. Food Research International, 41(9), 888–902. https://doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2007. 11.007. Fu, M., Sun, X., Wu, D., Meng, L., Feng, X., Cheng, W., et al. (2020). Effect of partial substitution of buckwheat on cooking characteristics, nutritional composition, and in vitro starch digestibility of extruded gluten-free rice noodles. LWT-Food Science & Technology, 126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109332. Article 109332. Gao, S. K., Yin, R., Wang, X. C., Jiang, H., Liu, X., Lv, W., et al. (2021). Structure characteristics, biochemical properties, and pharmaceutical applications of alginate lyases. Marine Drugs, 19(11). https://doi.org/10.3390/md19110628. Article 628. Goh, R., Gao, J., Ananingsih, V. K., Ranawana, V., Henry, C. J., & Zhou, W. (2015). Green tea catechins reduced the glycaemic potential of bread: An in vitro digestibility study. Food Chemistry, 180, 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. foodchem.2015.02.054 Goni, I., Garcia-Aionso, A., & Saura-Calixto, F. (1997). A starch hydrolysis procedure to estimate glycemic index. Nutrition Research, 17, 427–437. Hong, J., Li, C., An, D., Liu, C., Li, L., Han, Z., et al. (2019). Differences in the rheological properties of esterified total, A-type, and B-type wheat starches and their effects on the quality of noodles. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 44(3), Article e14342. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfpp.14342 Hong, T., Zhang, Y., Xu, D., Wu, F., & Xu, X. (2021). Effect of sodium alginate on the quality of highland barley fortified wheat noodles. LWT-Food Science & Technology, 140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110719. Article 110719. Hoover, R., & Hadziyev, E. D. (1981). Characterization of potato starch and its monoglyceride complexes. Starch, 33, 290–300. Jang, H., Bae, I. Y., & Lee, H. G. (2015). In vitro starch digestibility of noodles with various cereal flours and hydrocolloids. LWT - Food Science and Technology, 63(1), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2015.03.029 Kaur, N., Sharma, S., Yadav, D. N., Bobade, H., & Singh, B. (2017). Quality characterization of Brown rice pasta supplemented with vital gluten and hydrocolloides. Agricultural Research, 6(2), 185–194. http://doi:10.1007/s40003-0 17-0250-1. Li, Q., Wang, Y., Chen, H., Liu, S., & Li, M. (2017). Retardant effect of sodium alginate on the retrogradation properties of normal cornstarch and anti-retrogradation mechanism. Food Hydrocolloids, 69, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. foodhyd.2017.01.016 Lubowa, M., Yeoh, S. Y., Varastegan, B., & Easa, A. M. (2020). Effect of pre-gelatinised high-amylose maize starch combined with Ca2+-induced setting of alginate on the physicochemical and sensory properties of rice flour noodles. International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 56(2), 1021–1029. https://doi:10.1111/ijfs.14754. Lu, S., Na, K., Wei, J., Zhang, L., & Guo, X. (2022). Alginate oligosaccharides: The structure-function relationships and the directional preparation for application. Carbohydrate Polymers, 284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119225. Article 119225. Nitta, Y., Yoshimura, Y., Ganeko, N., Ito, H., Okushima, N., Kitagawa, M., et al. (2018). Utilization of Ca2+-induced setting of alginate or low methoxyl pectin for noodle production from Japonica rice. LWT-Food Science & Technology, 97, 362–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2018.07.027 Pineda-Gómez, P., Coral, D. F., Ramos-Rivera, D., Rosales-Rivera, A., & RodríguezGarcía, M. E. (2011). Thermo-alkaline treatment. A process that changes the thermal properties of corn starch. Procedia Food Science, 1, 370–378. https://doi:10.1016/j. profoo.2011.09.057. Ramírez, C., Millon, C., Nuñez, H., Pinto, M., Valencia, P., Acevedo, C., et al. (2015). Study of effect of sodium alginate on potato starch digestibility during in vitro digestion. Food Hydrocolloids, 44, 328–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. foodhyd.2014.08.023 Siddaramaiah, Swamy, T. M. M., Ramaraj, B., & Lee, J. H. (2008). Sodium alginate and its blends with starch: Thermal and morphological properties. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 109(6), 4075–4081. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.28625 Sun, X., Meng, L., & Tang, X. (2021). Retrogradation behavior of extruded whole buckwheat noodles: An innovative water pre-cooling retrogradation treatment. Journal of Cereal Science, 99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcs.2021.103234. Article 103234. Sun, X., Yu, C., Fu, M., Wu, D., Gao, C., Feng, X., et al. (2019). Extruded whole buckwheat noodles: Effects of processing variables on the degree of starch gelatinization, changes of nutritional components, cooking characteristics and in vitro starch digestibility. Food & Function, 10(10), 6362–6373. http://doi: 10.1039/c 9fo01111k. Wang, L., Shan, G., & Pan, P. (2014). A strong and tough interpenetrating network hydrogel with ultrahigh compression resistance. Soft Matter, 10(21), 3850–3856. http://doi:10.1039/c4sm00206g. Woolnough, J. W., Bird, A. R., Monro, J. A., & Brennan, C. S. (2010). The effect of a brief salivary alpha-amylase exposure during chewing on subsequent in vitro starch digestion curve profiles. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 11(8), 2780–2790. http://doi:10.3390/ijms11082780. Xu, X., Gao, C., Xu, J., Meng, L., Wang, Z., Yang, Y., et al. (2022). Hydration and plasticization effects of maltodextrin on the structure and cooking quality of extruded whole buckwheat noodles. Food Chemistry, 374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. foodchem.2021.131613. Article 131613. Yu, Z., Wang, Y., Chen, H., & Li, Q. (2018). Effect of sodium alginate on the gelatinization and retrogradation properties of two tuber starches. Cereal Chemistry, 95(3), 445–455. http://doi: 10.1002/cche.10046. Yu, Z., Wang, Y., Chen, H., Li, Q., & Wang, Q. (2018). The gelatinization and retrogradation properties of wheat starch with the addition of stearic acid and sodium alginate. Food Hydrocolloids, 81, 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. foodhyd.2018.02.041 Zhao, T., Li, X., Ma, Z., Hu, X., Wang, X., & Zhang, D. (2020). Multiscale structural changes and retrogradation effects of addition of sodium alginate to fermented and native wheat starch. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 163, 2286–2294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.09.094 10